Abstract

The traditional lunar landing buffering structure uses multi-stage aluminum honeycomb materials to absorb impact energy. However, due to irreversible deformation and abrupt acceleration changes during the buffering process, it fails to meet reusability and compliant buffering requirements. Additionally, star table detectors have short landing times, typically completing buffering and energy absorption within 1 s. Therefore, this study employs a PZT-driven reusable buffering mechanism for rapid response. The mechanical structure converts linear impact motion into rotational motion via a large lead screw nut, enabling bidirectional movement with a compact, lightweight design. Dynamic responses under varying impact forces were analyzed using finite element impact dynamics, revealing relationships among structural deformation, stress, strain, and impact force. The reasoning system based on Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy neural networks compensates for control lag. Buffering experiments at landing velocities of 2, 3, and 4 m/s showed maximum reverse accelerations of 1.94, 2.04, and 2.13 m/s², and experimental accelerations of 2.59, 2.73, and 2.97 m/s², respectively. Compared to the Chang’e-3 lander, the mechanism exhibits smaller and more stable acceleration changes. Main contributions include: (1) design of a new PZT-based reusable buffering mechanism; (2) development of an adaptive fuzzy neural network lag compensation strategy; (3) comprehensive simulation and experimental validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of human spaceflight, higher requirements are put forward for deep space star surface exploration technology and equipment. Ye et al. have repeatedly mentioned the importance of flexible buffer technology and walkable landing technology in future missions such as manned lunar landings and star-surface base construction1,2,3. Currently, the main mechanisms used for smooth cushion landing on the star surface are hydraulic, mechanical spring, magnetorheological fluid, airbag cushioning and collapsing energy absorption4,5,6,7,8,9. Among them, the aluminum honeycomb in the collapsed energy-absorbing type has become the mainstream buffer material at this stage with its good mechanical properties and high reliability. Yang et al.10 used metal aluminum honeycomb as the buffer material to carry out the lander single-leg drop shock buffer experiment and collect the foot-end force and the center-of-mass acceleration curves of the lifting bar, but the collapsed force is basically a constant value, and the sudden change of the acceleration exists in the node at the beginning of the buffer, which is impossible to be used repeatedly. Moreover, it is impossible to realize the soft buffer landing control, which greatly affects the landing stability and safety. Zhou et al.11 proposed a composite gradient honeycomb structure optimization method for a walkable lunar lander and verified that the maximum overload has been reduced to

\(\:20.06\) m/s² through numerical simulations and impact tests. However, due to the size constraints and mass limitations and the lack of flexibility in the cushioning acceleration profile during high-speed impacts, the performance is somewhat limited.

Yue et al.12 studied the energy absorption characteristics of a hydraulic buffer damper of a reusable launch vehicle in view of the optimization design and modeling method of a repeatable buffer mechanism. However, due to the influence of high and low temperatures in space, this method is likely to cause buffer leakage. Zhou et al.13 proposed an adaptive backstepping controller and an improved barycentric trajectory planning algorithm for the walkable lunar lander. Li et al.14 established a set of magnetorheological liquid damper system model for gun recoil control based on optimal control and fuzzy compensation technology. Because this technology is still in the research stage, it cannot be used in landing buffer mechanism temporarily. Zhou et al.15 proposed a bidirectional buffer and drive mechanism based on aluminum honeycomb material and motor drive, but the aluminum honeycomb material cannot be recovered after compression and can only be used for a single buffer landing. Therefore, it is important to develop a stable and reliable bidirectional buffer mechanism that can adapt to the complex lunar surface environment.

Traditional motors such as servo motors and stepper motors cannot meet the current technical requirements such as fast response and large thrust16. To solve this problem, many scholars have made use of strain-based forces in materials, such as piezoelectricity17, magnetostriction18, shape memory alloys19 and inchworm20. Among them, piezoelectric components have been widely used in the field of intelligent drive and precise operation due to their advantages such as small size, large output power, high precision, fast response and no magnetic field21,22.

Due to the lack of matching between inertia and friction force of PZT drive, hysteretic nonlinear control problem exists in the system motion process23,24. Wang et al.25 proposed a compact linear stick-slip PZT driver that can achieve high precision motion control. Yang et al.26 used the method of forward friction to balance reverse friction to suppress the reverse motion of PZT driven precision positioning platform. Zhao et al.27 realized the alternating motion of the drive wheel by using two stators powered by PZT, but it was difficult to adjust the friction between PZT and the drive wheel. Zhang et al.28 proposed a novel PZT friction damper to achieve precise control of friction by adjusting the voltage of piezoelectric stack actuators, and significantly improve the vibration response of large spatial structures. Sun et al.29 designed a PZT inertial impact driver based on the asymmetric friction principle to improve the stepping accuracy and motion stability. Li et al.30 proposed an auxiliary friction method to achieve a balance between miniaturization and efficient output performance by applying auxiliary friction to inertial impact piezoelectric actuators. Li et al.31 proposed an improved impact inertial drive to improve motion performance by optimizing friction structure.

Due to the complex operating environment of the buffer, it needs to operate stably under extreme conditions such as low gravity, high and low temperatures, and strong radiation. PZT, with its strong high and low temperature adaptability, radiation-resistant ceramic structure, and no mechanical wear, can effectively cope with sudden changes in overload acceleration during the buffering process. However, the inherent hysteresis nonlinearity of PZT can affect control accuracy. To address this, an adaptive compensation method based on T-S fuzzy neural network theory is employed to dynamically adjust the voltage input to PZT, thereby compensating for its nonlinearity and hysteresis effects during the driving process. Therefore, a novel repeatable buffer mechanism driven by PZT is proposed, with the following three main innovative features:

-

1.

A reusable buffer mechanism driven by PZT has been proposed to address the issues of non-reusability and sudden changes in overload acceleration in traditional buffer mechanisms.

-

2.

An adaptive fuzzy neural network control strategy was designed to effectively compensate for hysteresis nonlinearity in the system, enabling precise adjustment of the buffering force.

-

3.

Through finite element dynamic simulation and experimental verification under various landing speeds, the performance of the designed PZT-based reusable buffering mechanism in terms of reusability and handling sudden changes in overload acceleration was validated.

Structure design and working principle of the repeatable buffer mechanism

(Microsoft® PowerPoint® 2021MSO (Version 2505 Build 16.0.18827.20102) 64 bit. Figure 1. Schematic diagram of repeatable buffer mechanism.pptx)

A novel repeatable buffer mechanism driven by PZT is designed and fabricated based on interactive parametric modeling method. Figure 1 shows the structure principal diagram of the piezoelectric repeatable buffer mechanism. When the end of the mechanism is affected by the impact force, the screw nut produces spiral motion, converts the linear motion into rotating motion by rotating the screw, drives the rotating motion of the friction wheel, and generates normal positive pressure perpendicular to the rotating surface by the piezoelectric driver, so that the buffer mechanism obtains a large friction resistance, and in order to ensure that the reverse acceleration of the buffer is small, it is necessary to adjust the rotating range by piezoelectric.

Compared with other buffer mechanisms, the mechanism converts the instantaneous linear motion into rotating motion, and can complete the two-way buffer driving motion when combined with the driving structure. The developed repeatable buffer mechanism has fewer actuators, compact structure, meets the requirements of lightweight design, and the overall production is simple. The analytical models for calculating the transmission ratio, friction torque and input impact force are established. The main parameters were determined by sensitivity analysis, and the dynamic modeling of the mechanism buffering characteristics was carried out. By controlling the output force of PZT, adjusting the torque and amplifying the friction force of the mechanism can realize the motion control of the impact buffering process. The working principle is shown in Fig. 2. The gripper in the mechanism is a symmetrical flexure hinge structure, which is composed of two symmetrical semi-circular flexure hinges and right-Angle flexure hinges. Due to machining and assembly errors, large and irregular gaps may occur between the clamping unit and the rotor. To ensure that the rotor is stably clamped by the clamping unit, a lever-type amplifying mechanism is used to enhance the clamping displacement generated by PZT, and a similar structure is adopted for the clamping block. The right circular flexible hinge in the mechanism is the pivot around which the mechanism rotates. \(\:{l}_{A}\) is the length from the input end to the main point, \(\:{l}_{B}\) is the length from the output end to the main point, \(\:{x}_{A}\) is the input displacement of the input end, and \(\:{x}_{B}\) is the output displacement of the output end. The amplification factor of the lever mechanism can be calculated as.

(Microsoft® PowerPoint® 2021MSO (Version 2505 Build 16.0.18827.20102) 64 bit. Figure 2. Working principal diagram of rotary friction mechanism.pptx)

To save space, reduce weight, and improve the response time of the mechanism, the dimensions of \(\:{L}_{4}\) is the length from the lever fulcrum to the output end, which is 51.6 mm, and\(\:\:{L}_{6}\) is the length from the lever fulcrum to the input end, which is 20.6 mm, and the theoretical amplification coefficient of the lever-type amplification mechanism is approximately \(\:2.5\). The magnification factor is calculated by the following Eq. (2). \(\:{F}_{N}\) denotes the high-frequency thrust generated by PZT at both ends of the grippe. \(\:{F}_{Z}\) denotes the normal pressure that is transmitted and amplified by \(\:{F}_{N}\) through the gripper. The values of \(\:{x}_{A}\), \(\:{x}_{B}\) and \(\:{y}_{B}\) are all increased with the increase of the applied voltage. The specific parameters of the repeatable buffer mechanism, in Table 1.

The clamping force of the actuator is variable, and the torque and radius are non-variable. The variation of the clamping force can be used as an effective parameter for controlling the actuator’s rotational angle, speed, and acceleration at each step. When designing the repeatable buffer mechanism, the selection of key structural parameters is particularly important in order to realize high-precision friction adjustment and stable buffer performance.

Table 2 shows the key initial structural parameters of the repeatable buffer mechanism, including the number of piezoelectric elements, the design mass, and the maximum compressible distance, which provide the basis for the subsequent dynamic modeling and simulation analysis.

Dynamic modeling and simulation analysis of the repeatable buffer mechanism

Construction of the buffering dynamics model

The dynamics model of the repeatable buffer mechanism is established by the finite element simulation method of landing impact transient dynamics, analyzed, and parameters such as its center of mass acceleration, foot end force, and friction force are obtained. Among them, assuming that both the connecting rod and the motion mechanism are rigid bodies, considering the mutual coupling of the impact force at the foot end, the connecting rod motion, and the piezoelectric friction, the real-time interaction is expanded using the equivalent contact force method to realize the mapping of the impact force to the piezoelectric friction in order to obtain the parameters of the various sensors in the buffering process.

In Fig. 3, when the ball hinge at the end of the sliding rod is subjected to the impact force \(\:{F}_{a}\), the linear motion of the sliding rod prompts the nut to move and, at the same time, generates a large helical torque in the screw, which drives the friction wheel and the screw to rotate simultaneously through the ball screw sub-subsidiary. Thus, it can be obtained that the equivalent integrated impact force of the buffer mechanism is transformed into the torque of the screw \(\:{T}_{L}\), and the equivalent integrated inertia of the screw \(\:{J}_{L}\).

Where \(\:{P}_{h}\) denotes the lead of the ball-screw sub-assembly, \(\:\eta\:\) denotes the positive efficiency of the feed ball-screw sub-assembly, \(\:{F}_{a}\) denotes the impact force acting on the ball hinge at the end of the sliding rod, \(\:{J}_{s}\) denotes the rotational inertia of the ball-screw shaft, and m denotes the combined mass of the moving assembly and the driving load. The relationship between the rotational angular displacement \(\:{\theta\:}_{m}\) of the motor-driven ball-screw shaft and the linear displacement \(\:Z\) of the nut and actuator is presented as follows.

The moment of inertia and damping coefficient are defined as:

Where \(\:{J}_{e}\) denotes the equivalent moment of inertia of the output shaft of the friction rotor, \(\:{B}_{e}\) denotes the equivalent viscous damping coefficient of the output shaft of the friction rotor, \(\:{J}_{m}\) denotes the moment of inertia of the friction rotor, \(\:{B}_{m}\) denotes the viscous damping coefficient of the friction rotor, and \(\:{B}_{L}\) denotes the equivalent composite viscous damping coefficient of the load of the repeatable buffer mechanism.

A mathematical model of the mechanical system of the repeatable buffer mechanism can be derived from Newton’s second law of motion.

Where \(\:{T}_{em}\) denotes the friction torque generated by the friction rotor, \(\:\dot{{\theta\:}_{m}}\) denotes the mechanical angular velocity of the friction rotor and its connected ball-screw shaft. Let \(\:\dot{{\theta\:}_{m}}=\omega\:r\) then \(\:\omega\:p\:=\omega\:r\), \(\:\omega\:p\) denotes the angular velocity of the friction rotor.

Simulation of impact dynamics

To investigate the deformation, strain, and stress of the repeatable cushioning mechanism under diverse impact conditions, the finite-element simulation method for landing-impact transient dynamics was employed to analyze the cushioning mechanism. Tables 3 and 4 respectively list the material properties of its main components and the relevant parameters under three different impact conditions.

The deformation and strain of the gripper and nut under the impact force are analyzed by the finite element simulation method of transient impact dynamics. Figures 4 (A-C) shows the structural response under 10KN, 8KN and 6KN impact forces respectively, and analyzes the influence of different impact forces on the structural behavior.

By comparing Fig. 4, it can be found that with the increase of impact force, the deformation, strain, and stress concentration phenomena of the gripper and the nut become more and more obvious, which leads to the deterioration of the stability of the structure. When the impact force is gradually reduced, the deformation, strain, and stress distribution of the gripper and nut become more uniform, and the impact resistance and stability are significantly improved, and the structure shows the best cushioning performance and stability under the condition of a low impact force of 6 KN.

To analyze the dynamic response of the repeatable buffer mechanism under different impact force conditions, Figs. 5, 6 and 7 respectively show the deformation curve, strain curve and stress curve of the gripper and nut under different impact force. It is found that with the increase of impact force, the response of deformation, strain and stress becomes more significant, resulting in the worsening of structural instability. According to the maximum deformation, maximum strain and maximum stress between the gripper and the nut under different impact forces in Table 5, there is a significant positive correlation between the impact force and the deformation, strain and stress response of the structure.

Validation of simulation experiments

Construction of the piezoelectric friction buffering control system

To successfully carry out the research on the control method of the repeatable flexible buffer mechanism for the hysteresis nonlinearity of the piezoelectric driving process, based on the Takagi-Sugeno (T-S) fuzzy neural network, the framework of the fuzzy inference system with the training function of the adaptive learning function is established to obtain the fuzzy rules and fuzzy neural network controller. The linear quadratic regulator (LQR) control algorithm of optimal control theory is adopted to realize the information fusion of multi-sensors, and the fused information is used as the input of the fuzzy inference system, which is combined with Eq. (7), and the active control parameters are converted into the voltage input data, and the type and number of the affiliation functions of the input variables are set to obtain the affiliation function parameter of the globally optimal solution by calculating it based on the back-propagation algorithm and using it as the fuzzy neural network’s affiliation function and fuzzy control rule.

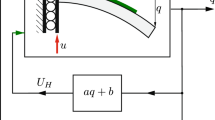

Where \(\:V\left(t\right)\) denotes the real-time control voltage of the PZT, \(\:f\left(t\right)\) denotes the sample data of the active control force, \(\:{N}_{0}\) denotes the preload force of the piezoelectric acting on the friction surface, \(\:{K}_{s}\) denotes the anti-slip coefficient, \(\:\dot{X}\left(t\right)\) denotes the friction velocity, \(\:{d}_{33}\) denotes the piezoelectric strain constant in the polarization direction, \(\:{k}_{33}\) dentes the electromechanical coupling coefficient, \(\:{n}_{1}\) denotes the number of piezoelectric, \(\:{n}_{2}\) denotes the number of friction surfaces and \(\:\mu\:\) denotes the actual control amount. The block diagram of the control system is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Before the experiment, the core objective of the control algorithm was to precisely control the PZT to regulate the friction force of the repeatable buffer mechanism, ensuring a smooth landing. The system is triggered by an impact stimulus to activate the reusable buffer mechanism. The reference trajectory generator generates optimized acceleration and displacement curves based on the set objectives and impact conditions. The system dynamically adjusts the control strategy in real-time based on acceleration and displacement data. The adaptive neural network performs optimal control on sample data using the LQR algorithm, while the T-S fuzzy neural network further optimizes the control strategy to ensure system stability. The fuzzy neural network controller executes the final control based on the optimized strategy, generating control signals to regulate the voltage \(\:V\left(t\right)\) and drive the PZT to produce high-frequency thrust \(\:{F}_{N}\) at both ends of the gripper. The gripper transmits and amplifies the positive pressure \(\:{F}_{Z}\), adjusting the friction force of the buffer mechanism to form a feedback loop, ensuring a smooth and reliable landing process.

.

Experimental parameters are set

Table 6 shows different landing conditions.

The experimental study of the drop - shock cushioning of repeatable buffer mechanism was carried out on a low - gravity simulation bench, the PZT model chosen was PI GmbH & Co.KG P − 844.60, and the servo - drive motor model was Unitree GO - M8010–6 which has a built - in encoder, with the specific parameters as shown in Tables 7 and 8. Precise control and fast response of PZT through the output signal of the power amplifier Aigtek ATA-P1005. The PZT and the signal amplifier cooperate with each other to control the friction force effectively by adjusting the voltage to precisely control the normal pressure between the friction surface and the friction surface, realizing the impact cushioning during the landing process of the repeatable buffer mechanism and providing a stable and smooth cushioning effect.

A new principal prototype of repeatable buffer mechanism based on piezoelectric drive was developed, and a supporting control system platform was built. According to the three landing conditions shown in Table 6 and the ground drop test platform shown in Fig. 9, the soft-landing experiment of the lander on one leg was carried out, so that the lander could complete the soft-landing experiment with variable friction damping force under precise control.

Schematic diagram of the single-leg impact testing device. The system includes a control unit (host computer and signal amplifier), an impact test stand with sliding guide rails and a mounting frame, a piezoelectric ceramic actuator for adjusting friction damping, and a simulated lunar regolith tank for impact testing.

To verify the dynamic response characteristics of the repeatable buffer mechanism and the effectiveness of the buffer performance at different landing speeds, three velocity parameters of 2 m/s, 3 m/s and 4 m/s were set. Based on the experimental process shown in Fig. 10, the acceleration and velocity curves of the simulation and real experiments were compared to evaluate the performance differences of the repeatable buffer mechanism under different working conditions. As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, and 13. The consistency between simulation results and actual experimental data was analyzed.

In Table 9, the error of simulation and experiment results is relatively small, in which the maximum acceleration error and maximum velocity error are 0.84 m/s2 and 0.34 m/s respectively. The buffer mechanism can effectively slow down the impact force at different landing speeds, showing good buffer performance. The error of experiment and simulation is due to insufficient simulation of the actual mechanical structure error, environmental factors and experimental environment in the simulation process. Although there are some differences in conditions, the trend of experiment and simulation results is similar, which also verifies the rationality of system design and the effectiveness of buffer control strategy.

Comparison of experimental results10.

The overload acceleration at the center of mass of Chang ‘e-3 lander at the landing speed of 3 m/s is compared with the overload acceleration in this paper. The black curve and the blue curve represent the acceleration of the center of mass and foot end of the suspension frame of Chang ‘e-3 respectively, and the red curve corresponds to the acceleration measured when the landing speed is 3 m/s in this study. To verify the performance advantages of the repeatable buffer mechanism, this study compares the measured data with the Chang’e-3 lander acceleration profile. Under different landing speed conditions, the measured maximum acceleration of the new cushioning mechanism is smaller than the acceleration of Chang’e-3 in Fig. 14, and the acceleration curves show better flexibility, and the sudden change of acceleration is reduced, which further verifies the stability and safety of the designed new repeatable buffer mechanism.

In addition to improvements in landing smoothness, this study has made significant contributions across multiple dimensions. First, compared to the landing cushioning mechanism of the Chang’e 3 mission, this mechanism converts instantaneous linear impact motion into rotational motion and, in conjunction with a PZT-driven structure, achieves bidirectional cushioning drive motion. PZT can operate stably under extreme conditions such as high/low temperatures and radiation, enhancing the mechanism’s adaptability to complex terrain. Second, the PZT-driven reusable cushioning mechanism is reusable. Unlike aluminum honeycomb materials, which undergo irreversible deformation due to compression, this design ensures the cushioning mechanism can be reused after each landing, significantly improving the system’s economic viability and sustainability. Additionally, we utilized T-S fuzzy neural networks and LQR optimization control to achieve real-time voltage regulation of the PZT, enabling dynamic adjustment of friction force and improving the smoothness and precision of the buffering process. Therefore, our PZT reusable buffering mechanism achieves innovations in smoothness, buffering performance, control precision, reusability, and environmental adaptability, thereby enhancing the system’s overall performance and application potential.

.

Conclusions and future work

To solve the deficiencies of traditional buffer technology in soft landing control, this paper proposes a new piezoelectric-driven repeatable buffer mechanism. When the end of the mechanism is subjected to an impact force, the screw nut generates a helical motion, and the rotating screw converts the linear motion into a rotational motion, and the piezoelectric actuator generates a normal positive pressure perpendicular to the rotating surface to realize the friction buffer. The mechanism significantly optimizes the flexibility of the acceleration curve, reduces the sudden acceleration change, and improves the flexibility of the landing process.

In terms of theoretical analysis, a finite element model based on impact dynamics is established to reveal the dynamic response characteristics of the buffer mechanism under different impact forces, including the quantitative relationship between structural deformation, strain, and stress distribution. It is shown that the buffer mechanism exhibits better stability and impact resistance under lower impact force conditions. In addition, for the hysteresis nonlinearity problem in the piezoelectric drive process, an adaptive hysteresis compensation method is proposed by using Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy neural network theory, which enhances the adaptive capability of the system control.

In the experimental validation part, the single-leg drop impact test was carried out on the constructed drop shock impact test platform, and the buffer performance was tested under three landing speed conditions, namely, 2 m/s, 3 m/s and 4 m/s. The simulated and experimental maximum accelerations were \(\:1.94\) m/s2 and \(\:2.59\) m/s2, and the maximum velocities were\(\:\:0.95\) m/s2 and \(\:0.95\) m/s2 respectively. When the landing speed is 2 m/s, the simulated and experimental maximum accelerations are \(\:1.94\) m/s2 and \(\:2.59\) m/s2, and the maximum velocities are 0.73 m/s and 0.95 m/s. When the landing speed is 3 m/s, the simulated and experimental maximum accelerations are \(\:2.04\) m/s2 and \(\:2.73\) m/s2, and the maximum velocities are 0.75 m/s and 0.99 m/s, respectively. When the landing velocity is 4 m/s, the simulated and experimental maximum accelerations are \(\:2.13\) m/s2 and \(\:2.97\) m/s2, and the maximum velocities are 0.78 m/s and 1.12 m/s, respectively.

In this study, the measured data are compared with the acceleration curve of the Chang’e-3 lander. Under different landing velocities, the measured maximum acceleration of the new cushioning mechanism is smaller than the acceleration of Chang’e-3 in Fig. 13, and the acceleration curves show better flexibility and reduced sudden changes in acceleration, which further verifies the stability and safety of the designed new repeatable cushioning mechanism. In the future, the performance of the mechanism under extreme environmental conditions will be optimized in depth to improve its adaptability, especially when facing higher impact and complex terrain conditions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during this study are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions on experimental prototype data, but are available from the corresponding author (Jinhua Zhou, 240008@sdjtu.edu.cn) upon reasonable request.

References

Peijian, Y. E., Dengyun, Y. U., Zezhou, S. U. N. & Zhenrong, S. H. E. N. Achievements and prospect of Chinese lunar probes. J. Deep Space Explor. 3 (4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.15982/j.issn.2095-7777.2016.04.004 (2016).

Lu, D., Liu, J. G. & Gao, H. B. Integrated exploration robots for planetary surface landing and patrolling: A review. Acta Aeronautica Et Astronaut. Sinica. 42 (1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.7527/S1000-6893.2020.23742 (2021).

Wang, Y., Wu, S. Q. & Jiang, W. S. Research progress of landing buffer technology of spacecraft. IEEE Sci. Technol. Eng. 21 (24), 10118–10126. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2021.24.004 (2021).

Yue, S., Titurus, B., Nie, H. & Zhang, M. Liquid spring damper for vertical landing reusable launch vehicle under impact conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 121, 579–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2018.11.034 (2019).

Rahmat, M. S. et al. Vibration control of gun recoil system with magneto-rheological damper associated with adaptive hybrid skyhook active force control. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 43 (5), 279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-021-03001-9 (2021).

Daneshjou, K. & Alibakhshi, R. Multibody dynamical modeling for spacecraft Docking process with spring-damper buffering device: a new validation approach. Adv. Space Res. 61 (1), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2017.10.036 (2018).

Pucker, T. Numerical study on modeling the soil footpad interaction of lunar soft Landers at touchdown. Comput. Geotech. 171, 106341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2024.106341 (2024).

Zhu, J. et al. Improving landing stability and terrain adaptability in lunar exploration with biomimetic lander design and control. Acta Astronaut. 226, 860–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2024.11.020 (2025).

He, C., He, H. & Wang, T. Similarity Design Method of the Inflatable Buffer Landing System. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 5326979 (2019) (2019). (1) https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5326979

Yang, J., Zeng, F., Man, J. & Zhu, W. Design and verification of the landing impact Attenuation system for Chang’E-3 lander. Sci. Sin Technol. 44 (5), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1360/092014-46 (2014).

Zhou, J., Ma, H., Jia, S. & Tian, S. Mechanical properties of multilayer combined gradient cellular structure and its application in the WLL. Heliyon 9 (4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14825 (2023).

Yue, S., Titurus, B., Li, Z., Wu, C. & Du, Z. Analysis of liquid spring damper for vertical landing reusable launch vehicle with network-based methodology. Nonlinear Dyn. 111 (3), 2135–2160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-022-07944-z (2023).

Zhou, J., Ma, H., Chen, J., Jia, S. & Tian, S. Motion characteristics and gait planning methods analysis for the walkable lunar lander to optimize the performances of terrain adaptability. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 132, 108030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2022.108030 (2023).

Li, Z., Gong, Y. & Wang, J. Optimal control with fuzzy compensation for a magnetorheological fluid damper employed in a gun recoil system. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 30 (5), 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X17754258 (2019).

Zhou, J., Jia, S., Qian, J., Chen, M. & Chen, J. Improving the buffer energy absorption characteristics of movable lander-numerical and experimental studies. Materials 13 (15), 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13153340 (2020).

Liu, X., Li, Y., Xia, L., Tan, X. & Cao, X. Research on permanent magnet synchronous motor algorithm based on linear nonlinear switching self-disturbance rejection control. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46881-8 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Miniaturized electromechanical devices with multi-vibration modes achieved by orderly stacked structure with piezoelectric strain units. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 6567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34231-7 (2022).

Gao, C., Zeng, Z., Peng, S. & Shuai, C. Magnetostrictive alloys: promising materials for biomedical applications. Bioactive Mater. 8, 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.06.025 (2022).

Rashidi, S., Ehsani, M. H., Shakouri, M. & Karimi, N. Potentials of magnetic shape memory alloys for energy harvesting. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 537, 168112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2021.168112 (2021).

Zheng, Z. et al. Piezoelectric soft robot inchworm motion by tuning ground friction through robot shape: Quasi-static modeling and experimental validation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 40, 2339–2356. https://doi.org/10.1109/TRO.2024.3353035 (2024).

Hong, Y. et al. A bioinspired surface tension-driven route toward programmed cellular ceramics. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 5030. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49345-3 (2024).

Yu, R. & Zhang, D. A. Thermal actuated bistable structure for generating On-Chip shock loads. Micromachines 13 (4), 569. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13040569 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Acceleration self-compensation mechanism and experimental research on shock wave piezoelectric pressure sensor. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 150, 107303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107303 (2021).

Liang, C. et al. A 2-DOF monolithic compliant rotation platform driven by piezoelectric actuators. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 67 (8), 6963–6974. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2019.2935933 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Design, analysis, experiments and kinetic model of a high step efficiency piezoelectric actuator. Mechatronics 59, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechatronics.2019.03.003 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. On the suppression of the backward motion of a piezo-driven precision positioning platform designed by the parasitic motion principle. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 67 (5), 3870–3878. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2019.2916295 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. Design and experimental research of a novel inchworm type piezo-driven rotary actuator with the changeable clamping radius. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 84 (1). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4788736 (2013).

Zhang, X., Luo, Q., Han, Q., Lu, Y. & Wang, Y. Hysteretic behaviour and structural control performance of a piezoelectric friction damper. Smart Mater. Struct. 32 (1), 015011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/aca6bd (2022).

Sun, W. et al. An impact inertial piezoelectric actuator designed by means of the asymmetric friction. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 70 (1), 699–708. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2022.3153807 (2022).

Li, X., Xu, Z., Sun, W. & Huang, H. An auxiliary friction method for miniaturizing the inertial impact piezoelectric actuators. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 71 (1), 777–787. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2023.3247772 (2023).

Li, X., Xu, Z., Wu, H. & Huang, H. On the performance improvement of a miniature impact inertial piezoelectric actuator for vertical positioning. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 71 (9), 11185–11194. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2023.3332989 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12302059), Laboratory of Aerospace Entry, Descent and Landing Technology Fun(EDL19092409),The Shandong provincial colleges and universities youth innovation technology support program (2024KJH002), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022QE199).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daoguang Han: Conceptualization, Methodology; Dongsheng Zhang: software, Writing-original draft; Jinhua Zhou: Supervision, Formal Analysis; He Jia: Writing - review& editing; Jishou Fang: Validation, Writing - review & Editing; Yongbin Wang: Investigation, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, D., Zhang, D., Zhou, J. et al. Design, analysis and experiment of a novel repeatable buffer landing mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 29175 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14598-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14598-5