Abstract

Compassion satisfaction (CS) refers to the positive emotional reward derived from helping others, particularly in healthcare settings. This study examines the influence of emotional and social loneliness, positive meaning of work, and organizational support on CS among primary care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this cross-sectional study, 261 professionals completed a questionnaire assessing emotional and social loneliness, positive meaning of work, perceived organizational support (POS), and professional quality of life. Results showed positive meaning of work as the strongest predictor of CS, followed by a negative association with emotional loneliness. While POS was positively related to CS, its contribution was comparatively modest, and social loneliness showed no significant effect. These findings suggest that CS among primary care professionals is more strongly associated with intrinsic work-related factors and emotional well-being than with external organizational conditions. Promoting a sense of meaning in work and addressing emotional loneliness may be key strategies for organizations to enhance professionals’ well-being and job satisfaction, fostering a more humane and balanced approach to medical practice that ultimately benefits both patient care and organizational efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary care plays a critical role within the healthcare system, encompassing a whole range of activities focused on health promotion and illness prevention, including treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care1. In recent years, public primary care services have faced unprecedented changes due to the increased demand for services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside government cuts to health and social care budgets2,3,4. These pressures have had a profound impact on healthcare professionals in primary care, placing additional strain on their work performance.

Healthcare professionals handle particularly stressful tasks due to the significant physical, cognitive, and emotional demands of their work.5,6,7,8,9. Burnout is a well-documented consequence of these demands, with negative impacts on both healthcare organizations and healthcare professionals. Organizations often face higher rates of absenteeism, increased sick leave, and errors in clinical judgment and treatment, while professionals are prone to anxiety, sleep disorders, hyperarousal, irritation, feelings of impotence, apathy, and depression7,9,10,11,12,13,14. Despite these challenges, many professionals report personal growth and fulfillment from their work, highlighting the dual nature of caring professions10,15,16,17. Thus, burnout—often referred to as ‘the cost of caring’18—and the sense of reward from helping others coexist in the everyday experience of healthcare professionals19,20.

Stamm’s Professional Quality of Life model (ProQOL) provides a framework for understanding the dual outcomes of working in healthcare: Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction (CS)16. Compassion fatigue refers to the negative result of ongoing exposure to others’ suffering, which includes “burnout” and secondary traumatic stress. Conversely, CS refers to the positive aspects of caring for others, including the sense of accomplishment and reward that comes from helping alleviate patient suffering16. Traditionally, much of the research in this area has focused on the negative effects of CF7,21,22. However, an increasing body of literature is exploring the factors that promote CS and its potential benefits for healthcare professionals11,23,24,25,26,27.

CS has been associated with professionals’ positive work experience and overall well-being. The current research seeks to address a critical gap in the literature by investigating the protective factors that may promote CS among primary care professionals. Given the increasing pressures in primary care, such as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and budgetary constraints, there is an urgent need to identify factors that can improve both organizational effectiveness and professional well-being. As we will describe in the following sections, the study draws on theories from work and organizational psychology, which suggest that perceived organizational support (POS) and meaning of work are associated with improved job satisfaction and well-being. By exploring these associations together with the negative impact of loneliness, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of both protective and risk factors in the healthcare context.

POS, meaning of work, and CS

POS refers to employees’ beliefs about the extent to which their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being28,29. Empirical evidence has consistently shown that higher levels of POS are associated with greater job satisfaction, improved work engagement and lower turnover intentions28,29. In healthcare settings, these positive outcomes could be linked to enhanced CS, reflecting a reciprocal benefit for both the professional and the organization. Moreover, Sodeke-Gregson et al.30 examined the prevalence and predictors of CS, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among therapists, finding that perceived management support and supervision were significant predictors of CS. Likewise, a more recent study by Spinola and Krylborn31 found the same positive correlation between CS and POS in a sample of specialist nurses during the pandemic.

Similarly, the positive meaning of work, defined as the personal significance and value that individuals attribute to their professional roles, has been identified as a crucial factor in fostering intrinsic motivation, professional fulfillment, and overall well-being32,33,34. In healthcare, where professionals are uniquely tasked with alleviating suffering and saving lives34,35,36, a strong sense of work meaning is particularly relevant. The desire to heal is a key motivator for many healthcare professionals37,38,43, and higher levels of work meaning have been associated with improved job performance and an enhanced ability to manage stress, thereby potentially elevating CS36,37,38. These findings support the notion that, in healthcare settings, an elevated sense of meaning in work may directly contribute to higher CS while also acting as a protective factor against burnout and compassion fatigue. In addition, the relationship between POS and work meaning is crucial, particularly in high-demand healthcare settings where emotional and ethical challenges are prominent36,38. POS fosters a work environment where employees feel valued and supported, which enhances their sense of purpose and fulfillment. When professionals perceive that their organization genuinely cares about their well-being and professional growth, they are more likely to experience their work as meaningful32. This positive perception strengthens their commitment, resilience, and capacity to cope with challenges, ultimately contributing to greater CS. Empirical evidence has shown that organizational support—through recognition, adequate resources, and effective supervision—not only improves job satisfaction but also reinforces the intrinsic motivation to help others, a fundamental aspect of meaningful work in healthcare39. Therefore, organizations that prioritize employee support mechanisms may also facilitate a deeper sense of purpose and professional fulfillment, which is essential for both improved patient care and the overall well-being of healthcare workers.

Loneliness and CS

Loneliness represents a significant public health concern that affects both psychological and physical health40,41. Defined as a subjective and distressing experience, loneliness is traditionally divided into social loneliness, referring to the lack of relationships with others, and emotional loneliness, characterized by intense feelings of emptiness and abandonment41,42. Importantly, emotional loneliness does not necessarily coincide with objective social isolation; a socially isolated person is not necessarily lonely, and a lonely person is not necessarily socially isolated41. Emotional loneliness may create a profound internal disconnection that makes it difficult for professionals to connect with patients in caregiving roles, thereby hindering the development of CS and its benefits. Recent studies indicate that loneliness negatively impacts psychological and physical health and longevity, and in the context of the workplace, emotional loneliness has been shown to contribute to burnout among healthcare professionals43,44. In addition, loneliness has been associated with diminished organizational effectiveness, as evidenced by increased absenteeism and higher turnover intentions45,46,47. Although research on the specific relationship between loneliness and CS in healthcare settings remains limited, Phillips et al.48 found that loneliness was the strongest predictor of burnout and lower CS in oncology nurses. These findings support the notion that higher levels of loneliness, particularly emotional loneliness, are likely associated with lower CS. By integrating loneliness into our model, alongside protective factors such as POS and positive meaning of work, our study aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing CS among primary care professionals.

The present study

Although there has been growing interest in CS, research on its antecedents remains limited, particularly among primary care professionals. Most existing studies have focused on specialized medical settings such as emergency services, intensive care, palliative care, or oncology, and have primarily examined burnout and stress rather than protective factors that could foster professional well-being. Given the escalating pressures in primary care, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and budgetary constraints, identifying key predictors of CS is critical for developing evidence-based interventions aimed at improving professionals’ quality of life and, ultimately, patient care and organization efficiency. To address this gap, the present study examines the role of two protective factors, POS and positive meaning of work, and one risk factor, loneliness, in predicting CS among primary care professionals. Based on previous research, we hypothesize that POS and positive meaning of work will be positively associated with CS, whereas both emotional and social loneliness will be negatively related to CS.

Method

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional study using an online survey hosted by Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT, USA). The main outcome measure was CS, the independent variables were meaning of work, POS and loneliness. We also assessed and explored the relationship of other variables, including professional experience.

Participants

The participants in this study were primary care professionals from the Primary Care Service of the Tenerife Area. The eligibility criteria were: (1) being actively employed within the Primary Care Service of the Tenerife Area; (2) working in a primary care center in a healthcare or administrative role that involves direct interaction with patients. The recruitment strategy was convenience sampling. The survey link was shared through the Primary Care Service’s internal communication network. Data collection occurred between June and October 2022.

Instruments

Work as Meaning Inventory (WAMI33): The validated Spanish version of WAMI was used to measure the Dimension of Positive Meaning of Work32. This sub-scale assessed the experience of work having a purpose, with four items (e.g.,“I have found a meaningful career”). The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The coefficient Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale41. The Spanish translation49 of the short form was utilized to assess Emotional Loneliness and Social Loneliness through 6 items. Social loneliness manifests the objective lack of an individual wider social network (3 items; e.g., “There are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems”), while emotional loneliness is characterized by intense feelings of emptiness, abandonment, and forlornness (3 items; e.g., “I experience a general sense of emptiness”). Respondents provided responses on a three-point scale: “no”, “more or less”, and “yes.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.77 for emotional loneliness, and 0.83 for social loneliness.

Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (POS). The Spanish version of the short-form POS scale50 assesses the extent to which employees perceive the organization values their contributions and cares about the well-being of its workers (8 items; e.g., “This hospital really cares about my well-being”). Participants rate their agreement level on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained for this scale was 0.92.

Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL). The Spanish IV version of ProQOL51 was employed to assess the CS subscale, focusing on the positive aspects of working as a healthcare professional (10 items; e.g., “I get satisfaction from being able to help people”). Responses on this scale range from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained for this subscale was 0.88.

Study size

Considering that in the Primary Care Service of the Tenerife Area there are approximately a total of 1877 professionals, considering the structural workforce, it was estimated that a sample size of 92 was necessary for a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 10%.

Statistical methods

Cases were selected if the participant had answered at least 95% of the items. To describe the professionals’ profile, we utilized descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, and frequencies. To explore the relationships between professional experience, positive meaning of work, POS, loneliness, and CS we conducted Spearman correlation analysis, as the variables were not normally distributed.

In order to build a prediction model for CS, we initially considered using multiple linear regression. However, given the non-normal distribution of the variables, as evidenced by the Shapiro–Wilk test results, along with the heteroscedasticity and non-normal distribution of the linear model’s residuals, we ultimately chose binary logistic regression, discretizing both the target and predictor variables based on their median values. Regarding missing data, the column median value of the variable was imputed if the column had less than 5% missing values. Lastly, since this was a cross-sectional study, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to assess whether the data was affected by Common Method Variance. The Exploratory Factor Analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for only 32.3% of the variance, indicating that CMV was unlikely to be a significant concern.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Laguna (Register CEIBA 2020-0418). All participants gave written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Participants

A total of 261 professionals participated, with 242 completing all the measures. The participants were predominantly female (75%), of middle age (M = 44.58; SD = 10.13). The most represented profession was nursing (43%), followed by primary care physicians (26%) and administration staff (19%). Additionally, there were representations of other professional profiles such as nursing assistants, psychologists, social workers, and others, each of which accounted for less than 3% of the sample (Table 1).

Descriptive data

Professionals showed a broad range of work experience ranging from less than one year to 42 years (M = 16.20; SD = 10.49). Participants reported a moderate to high level of meaningfulness in their work and a moderate level of POS. Concerning CS, they exhibited moderate levels. In terms of social and emotional loneliness, they showed low to medium levels. No significant differences were observed among professional categories (Table 2).

The variables did not follow a normal distribution. They exhibited negative skewness in measures of positive meaning of work, CS, and POS, indicating that higher scores were more common. Conversely, positive skewness was observed in loneliness factors, suggesting that lower scores were more prevalent.

Correlational analysis

Positive meaning of work showed significant positive relation with CS (r(240) = 0.66, p < 0.001) and POS (r(240) = 0.28, p < 0.001); and significant negative relation with emotional loneliness (r(240) = -0.26, p < 0.001) and social loneliness (r(240) = − 0.19, p < 0.001). CS was positively associated with POS (r(240) = 0.29, p < 0.001); and negatively associated with emotional loneliness (r(240) = − 0.32, p < 0.001) and social loneliness (r(240) = − 0.20, p = 0.002). POS was negatively correlated with emotional loneliness (r(240) = − 0.22, p < 0.001) and social loneliness (r(240) = − 0.17, p = 0.008). Emotional loneliness was positively associated with social loneliness (r(240) = 0.55, p < 0.001). Finally, professional experience was not associated with other variables (Table 3).

Predicting CS based on the positive meaning of work, POS, and loneliness

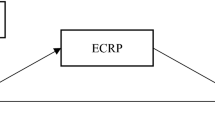

A logistic regression was performed to examine the effects of the positive meaning of work, POS, emotional loneliness, and social loneliness on the likelihood of having high CS versus low CS. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2 (4, 237) = 72.612, p < 0.001. The model explained 34.6% of the variance in CS (Nagelkerke R2) and correctly classified 74.0% of cases (79% of low CS; 69% of high CS). The logistic regression model yielded an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.803 (Fig. 1), which indicates the model’s ability to discriminate between high and low CS levels. An AUC value close to 1 suggests a strong discriminatory power. In this case, an AUC of 0.803 demonstrates the model’s good level of discrimination.

Professionals who reported a high level of positive meaning in their work were approximately eight times more likely to experience a high level of CS compared to those who reported low positive meaning in their work (OR = 7.917, p < 0.001). Additionally, professionals who reported high levels of emotional loneliness were approximately seven times less likely to demonstrate high CS (OR = 0.320, p < 0.002). The estimate for POS in the logistic regression indicated a positive but marginally significant relationship with the prediction of CS (OR = 1.690, p = 0.087). Lastly, social loneliness did not emerge as a significant predictor of CS (Table 4).

Although all participants had patient-facing responsibilities, there was a relevant axis of heterogeneity (physicians and nurses vs. other primary care staff) that warranted examination of its potential impact. For this reason, the same predictive model was developed using only the subset of healthcare professionals (physicians and nurses, n = 166). This model also demonstrated a significant fit: χ2(4, 161) = 65.593, p < 0.001. The Nagelkerke R2 was 0.436, indicating a moderate explanatory power. The model correctly classified 78.9% of cases (80.7% of low CS and 76.9% of high CS), with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.840, showing results comparable to those of the overall model. Likewise, the direction and significance of the predictors were consistent with the results obtained in the model that included all participants (Table 5).

Lastly, a logistic regression model could not be applied to the group of other primary care staff due to the small sample size (n = 76).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the role of POS, positive meaning of work, and loneliness in predicting CS in a sample of primary care professionals. Our results demonstrate that high CS scores are strongly correlated with a positive sense of work and lower levels of emotional loneliness. While POS does play a role, it is less influential than the positive meaning of work and emotional loneliness; notably, social loneliness does not have a significant effect in predicting CS. Our model accurately classified 74% of cases in terms of high or low CS. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show the significant impact of the positive meaning of work and emotional loneliness on CS among primary care professionals. These insights are essential for designing effective interventions aimed at improving professionals’ well-being and job satisfaction, as well as healthcare organization efficiency.

Findings

The findings are consistent with the professional quality-of-life model, which identifies CS as an important factor in professionals’ well-being and patient outcomes, reflecting the rewarding experience of providing patient care16,30,52. However, research on the antecedents of CS in primary care remains limited, particularly in light of recent challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, workforce shortages, and budget constraints, all of which have further compromised professional well-being. This study identifies three key predictors of CS:

-

1.

Positive meaning of work emerged as the strongest positive predictor. Primary care professionals who perceive their work as meaningful report substantially higher levels of CS.

-

2.

Emotional loneliness showed a significant negative association with CS. Feelings of emptiness or emotional disconnection undermine professionals’ ability to derive satisfaction from patient care.

-

3.

POS was positively related to CS, but to a lesser extent. Social loneliness, in contrast, did not show a statistically significant impact.

These results suggest that CS in primary care professionals tends to be more strongly associated with the intrinsic factors, such as the value and significance of the profession and emotional well-being, than to more external factors, such as POS or social connectedness. Supporting this, healthcare professionals often view their ability to interact compassionately with patients as a unique and essential part of their role53. Moreover, recent studies indicate that emotional loneliness —characterized by intense feelings of emptiness, abandonment, and forlornness— particularly undermines their ability to derive satisfaction from patient care. Managing work-related emotions in isolation can lead to emotional loneliness among healthcare professionals48,54. Therefore, the development of evidence-based interventions to improve CS of primary care professionals should prioritize strategies that enhance the positive sense of work and reduce emotional loneliness, thereby promoting professional quality of life and well-being, and ultimately improving both patient care and organizational efficiency.

Theoretical and practical implications

Understanding the mechanisms that drive CS in healthcare professionals can inform both theoretical models and practical interventions that foster a more supportive and fulfilling work environment. In this line, an integrative approach such as Social Exchange Theory55 may help to strengthen the theoretical foundations of our results. From the perspective of Social Exchange Theory, POS promotes CS by shaping a reciprocal relationship between professionals and their organizations. When professionals perceive strong organizational support, they are more likely to experience a sense of duty and trust, which enhances their engagement and commitment to their work. The interplay between these mechanisms suggests that when healthcare professionals feel supported, they not only find greater meaning in their roles but also reciprocate through heightened CS, ultimately benefiting both their personal fulfillment and patient care quality.

Another promising approach to improving the quality-of-life of primary care professionals is the patient-centered care model56,57. This approach emphasizes understanding patients’ needs holistically while acknowledging that healthcare professionals also have emotional responses that can affect their practice. Adopting this model could benefit both patients and health professionals by fostering a more humane and balanced approach to medical practice58. However, empirical evidence shows that healthcare professionals often struggle to recognize their own emotional issues, and many believe they can manage stress independently4,59. Finally, the feasibility of implementing such a model in the current context of healthcare systems—marked by budget cuts, understaffing, overwhelming workloads, and precarious employment conditions60—will require profound structural as well as personal changes.

It is important to note that while our results indicate that intrinsic factors are more associated with CS than extrinsic ones, the responsibility for ensuring professional well-being should primarily rest with the organization, rather than with the individual. Organizational efforts are critical in this area, as recent studies have highlighted the negative impact of loneliness on organizational effectiveness, such as higher rates of absenteeism and turnover intentions45,46,61. To enhance healthcare professionals’ sense of purpose and reduce emotional loneliness, organizations should promote strong team relationships based on mutual support and cooperation47 and encourage open communication and emotional safety within healthcare systems48. Additionally, fostering self-care practices like regular exercise, good sleep habits, a balanced diet, and stress-relief activities—such as spending time in nature or engaging in hobbies—could improve professionals’ job satisfaction and overall well-being, ultimately improving patient outcomes and organizational effectiveness2,4,58,61.

Limitations

Several weaknesses should be considered. First, the cross-sectional design of the study limits our ability to draw causal inferences (for example, we cannot determine whether emotional loneliness leads to lower CS in primary care professionals or if lower levels of CS contribute to feelings of emotional loneliness). Future studies could benefit from employing experimental designs or neuroscientific techniques to deepen understanding of the interconnectedness of CS, positive meaning of work, and emotional loneliness. Additionally, the use of a convenience sample limits the generalizability of the results, and reliance on self-reported data could introduce biases. Furthermore, the study does not include several factors that may affect CS, such as organizational characteristics (size, type of clinical setting) and personal traits (coping strategies, emotional skills). Another potential limitation of this study is that it was conducted during the pandemic, which may have influenced the results. Future research should verify whether the patterns obtained persist in healthcare settings beyond the pandemic context. Moreover, the sample had a higher proportion of women than men, mirroring the gender distribution of the target population and thereby enhancing the external validity of the findings. However, this imbalance limited the analysis of the effect of gender on CS. Additionally, due to the small size and heterogeneity of the “Other primary care staff” group, it was not possible to explore in depth the effect of occupational role. Finally, as this study was conducted within Spain’s National Health Service, the findings may not be directly transferable to other countries. Thus, further validation of the predictive model for CS across diverse healthcare systems and contexts is warranted.

Conclusion

In 2015, the WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies published a comprehensive study showing that Spanish primary care ranked among the three strongest in Europe62. Its strengths included well-trained professionals, teamwork among various health disciplines (family medicine, pediatrics, nursing, and other professionals), effective access to the system and referral pathways, a broad service portfolio, nearly universal coverage, and good geographical and scheduling accessibility. However, perceptions of the healthcare system have deteriorated over the last years due to the impact of cuts and privatization policies63.

The current context of austerity, uncertainty, and chronic understaffing raises a pressing, unresolved question: How can healthcare professionals continue to provide the quality of care patients deserve while preserving their own CS, self-care practices, and positive connection to their work? Without adequate public investment, professionals are forced to navigate a delicate balance between patient care and their own well-being—often at the cost of moral distress36,64. Working in environments where personal and institutional values diverge erodes both CS and the positive meaning of work3,36. In such settings, how can professionals avoid feelings of loneliness, abandonment, or disillusionment? One possible answer, especially in the current context, lies in reclaiming—both individually and collectively—a fair distribution of public resources, and in actively participating, whether as caregivers or as patients, in shaping the kind of humane and compassionate healthcare system we all aspire to.

This study underscores the crucial role of the meaning of work and emotional loneliness in predicting CS among primary care professionals. While POS contributes to CS, its influence is less pronounced than that of intrinsic work-related factors and emotional well-being. Theoretically, this study extends existing models of CS by applying principles of Social exchange theory to understand how POS promotes meaningful work experiences and emotional well-being. This integration offers a novel perspective for future research on professional quality of life in primary healthcare settings. At an applied level, these findings highlight the importance of developing interventions that strengthen professionals’ sense of purpose and alleviate emotional loneliness to enhance job satisfaction and overall well-being. As healthcare systems continue to face significant challenges, adequate public investment in healthcare organizations is essential to cultivate a supportive workplace culture, promote teamwork, and implement measures that enhance professionals’ emotional well-being, which ultimately benefits both the quality of patient care and organizational efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Primary Health Care (2023).

Alabi, R. O. et al. Mitigating burnout in an oncological unit: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 9, 677915 (2021).

Pavlova, A., Paine, S. J., Sinclair, S., O’Callaghan, A. & Consedine, N. S. Working in value-discrepant environments inhibits clinicians’ ability to provide compassion and reduces well-being: A cross-sectional study. J. Intern. Med. 293, 704–723 (2023).

Shanafelt, T. D. & Noseworthy, J. H. Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 92, 129–146 (2017).

Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J. & Cruz, B. Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 60, 1–11 (2016).

Hunsaker, S., Chen, H. C., Maughan, D. & Heaston, S. Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 47, 186–194 (2015).

Lluch, C., Galiana, L., Doménech, P. & Sansó, N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction in healthcare personnel: A systematic review of the literature published during the first year of the pandemic. Healthcare 10, 364 (2022).

Neville, K. & Cole, D. A. The relationships among health promotion behaviors, compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in nurses practicing in a community medical center. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 43, 348–354 (2013).

Sansó, N., Galiana, L., Oliver, A., Tomás-Salvá, M. & Vidal-Blanco, G. Predicting professional quality of life and life satisfaction in Spanish nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 4366 (2020).

Craig, C. D. & Sprang, G. Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout in a national sample of trauma treatment therapists. Anxiety Stress Coping 23, 319–339 (2010).

Gonzalez-Mendez, R., Díaz, M., Aguilera, L., Correderas, J. & Jerez, Y. Protective factors in resilient volunteers facing compassion fatigue. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 1769 (2020).

Hofmeyer, A., Kennedy, K. & Taylor, R. Contesting the term ‘compassion fatigue’: Integrating findings from social neuroscience and self-care research. Collegian 27, 232–237 (2020).

Petrino, R., Riesgo, L. G. & Yilmaz, B. Burnout in emergency medicine professionals after 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic: A threat to the healthcare system?. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 29, 279–284 (2022).

Salyers, M. P. et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 32, 475–482 (2016).

Larsen, D. & Stamm, B. H. Professional quality of life and trauma therapists. In Trauma, Recovery and Growth: Positive Psychological Perspectives on Posttraumatic Stress (eds Joseph, S. & Linley, P. A.) 275–293 (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

Stamm, B. H. Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue version 5 (ProQOL) (2009).

Stamm, B. H. Helping the helpers: Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in self-care, management, and policy of suicide prevention hotlines. In Resources for Community Suicide Prevention (eds Kirkwood, A. D. & Stamm, B. H.) (Idaho State University, 2012).

Boyle, D. A. Compassion fatigue: The cost of caring. Nursing 45, 48–51 (2015).

Hăisan, A. et al. Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among Romanian emergency medicine personnel. Front. Med. 10, 1189294 (2023).

Timofeiov-Tudose, I. G. & Măirean, C. Workplace humour, compassion, and professional quality of life among medical staff. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 14, 2158533 (2023).

Mol, M. M. C., Kompanje, E. J. O., Benoit, D. D., Bakker, J. & Nijkamp, M. D. The prevalence of compassion fatigue and burnout among healthcare professionals in intensive care units: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 10, 0136955 (2015).

Sinclair, S., Raffin-Bouchal, S., Venturato, L., Mijovic-Kondejewski, J. & Smith-MacDonald, L. Compassion fatigue: A metanarrative review of the healthcare literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 69, 9–24 (2017).

Gonzalez-Mendez, R. & Díaz, M. Volunteers’ compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and post-traumatic growth during the SARS-CoV-2 lockdown in Spain: Self-compassion and self-determination as predictors. PLoS ONE 16, 0256854 (2021).

Radey, M. & Figley, C. The social psychology of compassion. Clin. Soc. Work J. 35, 207–214 (2007).

Stalker, C. A., Mandell, D., Frensch, K. M., Harvey, C. & Wright, M. Child welfare workers who are exhausted yet satisfied with their jobs: How do they do it?. Child Fam. Soc. Work 12, 182–191 (2007).

Thomas, J. T. & Otis, M. D. Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: Mindfulness, empathy, and emotional separation. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 1, 83–98 (2010).

Trompetter, H. R., Kleine, E. & Bohlmeijer, E. T. Why does positive mental health buffer against psychopathology? An exploratory study on self-compassion as a resilience mechanism and adaptive emotion regulation strategy. Cogn. Ther. Res. 41, 459–468 (2017).

Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S. & Lynch, P. Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 82, 812–820 (1997).

Rhoades, L. & Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 698–714 (2002).

Sodeke-Gregson, E. A., Holttum, S. & Billings, J. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in UK therapists who work with adult trauma clients. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 4, 21869 (2013).

Spinola, M. & Krylborn, C. Specialist Nurses’ Compassion Fatigue and Related Factors in the Aftermath of COVID-19: A Correlation Survey (Umeå University, 2023).

Duarte-Lores, I., Rolo-González, G., Suárez, E. & Chinea-Montesdeoca, C. Meaningful work, work and life satisfaction: Spanish adaptation of work and meaning inventory scale. Curr. Psychol. 42, 12151–12163 (2023).

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J. & Duffy, R. D. Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory WAMI. J. Career Assess. 20, 322–337 (2012).

Faro, I., Campos, R., Dias, L. & Brito, A. Primary health care services: Workplace spirituality and organizational performance. J. Organ. Change Manag. 27, 59–82 (2014).

Malloy, D. C. et al. Finding meaning in the work of nursing: An international study. Online J. Issues Nurs. 20, 1 (2015).

Tong, L. Relationship between meaningful work and job performance in nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 24, 12620 (2018).

Lown, B. A., Shin, A. & Jones, R. N. Can organizational leaders sustain compassionate, patient-centered care and mitigate burnout?. J. Healthc. Manag. 64, 398–412 (2019).

Thienprayoon, R. et al. Organizational compassion: Ameliorating healthcare workers’ suffering and burnout. J. Wellness 3, 1 (2022).

Sainz, M., Delgado, N. & Moriano, J. A. The link between authentic leadership, organizational dehumanization and stress at work. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 37, 85–92 (2021).

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C. & Berntson, G. G. The anatomy of loneliness. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 12, 71–74 (2003).

Jong Gierveld, J., Tilburg, T. G. & Dykstra, P. A. Loneliness and social isolation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships (eds Perlman, D. & Vangelisti, A.) 485–500 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Weiss, R. S. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation (MIT Press, 1973).

Rogers, E., Polonijo, A. N. & Carpiano, R. M. Getting by with a little help from friends and colleagues: Testing how residents’ social support networks impact loneliness and burnout. Can. Fam. Physician 62, e677–e683 (2016).

Seppälä, E. & King, M. Burnout at work isn’t just about exhaustion. It’s also about loneliness. Harv. Bus. Rev. 29, 2–4 (2017).

Kose, S. & Özmen, A. Ö. Loneliness: From individualistic loneliness to workplace loneliness. In Current debates in social sciences (eds Koç, S. A. et al.) 145–156 (IJOPEC Publication, 2021).

Bowers, A., Wu, J., Lustig, S. & Nemecek, D. Loneliness influences avoidable absenteeism and turnover intention reported by adult workers in the United States. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 9, 312–335 (2022).

Arslan, A., Yener, S. & Schermer, J. A. Predicting workplace loneliness in the nursing profession. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 710–717 (2020).

Phillips, C., Becker, H. & Gonzalez, E. Psychosocial well-being: An exploratory cross-sectional evaluation of loneliness, anxiety, depression, self-compassion, and professional quality of life in oncology nurses. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 25(530), 8 (2021).

Buz, J. & Pérez-Arrechaederra, D. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Spanish version of the 11-item De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 26, 1553–1564 (2014).

Ortega, V. Adaptación al castellano de la versión abreviada de survey of perceived organizational support. Encuentros Psicol. Soc. 1, 3–6 (2003).

Stamm, B. H. Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue subscales, R-IV (ProQOL, 2009). Available at: https://proqol.org/proqol-measure.

Laserna-Jimenez, C., Casado-Montanes, I., Carol, M., Guix-Comellas, E. M. & Fabrellas, N. Quality of professional life of primary healthcare nurses: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 31, 1097–1112 (2022).

Ekman, E. & Halpern, J. Professional distress and meaning in health care: Why professional empathy can help. Soc. Work Health Care 54, 633–650 (2015).

Phillips, C. S. & Volker, D. Riding the roller coaster: A qualitative study of oncology nurses’ emotional experience in caring for patients and their families. Cancer Nurs. 43, 283–290 (2020).

Cook, K. S., Chesire, C., Rice, E. R. & Nakagawa, S. Social exchange theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology (ed. Delamater, J.) 61–88 (Kluwer Academic, 2013).

Mead, N., Bower, P. & Hann, M. The impact of general practitioners’ patient-centredness on patients’ post-consultation satisfaction and enablement. Soc. Sci. Med. 55, 283–299 (2002).

Stewart, M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care: The patient should be the judge of patient centred care. The BMJ 322, 444–445 (2001).

Sturgiss, E. A. et al. Who is at the centre of what? A scoping review of the conceptualisation of ‘centredness’ in healthcare. BMJ Open 12, 059400 (2022).

Navalpotro-Pascual, S. et al. Experiences of Spanish out-of-hospital emergency workers with high levels of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Arch. Public Health 82, 15 (2024).

Mijatović, D. Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe (2023).

LaBella, M. & Knippenberg, D. Workplace loneliness: Relationships with abstract entities as substitutes for peer relationships. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 54, 628–643 (2024).

Kringos, D., Boerma, W., Hutchinson, A. & Saltman, R. Building Primary Care in a Changing Europe 1–174 (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2015).

Lamata Cotanda, F. Atención Primaria en España: Logros y desafíos. Rev. Clínica Med. Fam. 10, 164–167 (2017).

Bauer-Wu, S. & Fontaine, D. Prioritizing clinician wellbeing: The university of Virginia’s compassionate care initiative. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 4, 16–22 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. E.C performed statistical analysis and data interpretation; additionally, reviewed and edited the manuscript for technical accuracy. E.L was responsible for data collection and provided support in drafted the initial version of the manuscript. V.M supervised the project and provided critical feedback as well as further revisions to the manuscript throughout all stages. N.D conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morera, Y., Callejas, E., Lorenzo, E. et al. The role of loneliness, work meaning and organizational support in compassion satisfaction among primary care professionals during the pandemic. Sci Rep 15, 29852 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14602-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14602-y