Abstract

To ensure smooth closure of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges and compliance of structural geometric alignment/stress with design requirements, this study employs finite element modeling to analyze the impact of variations in key construction control parameters during cantilever construction on bridge alignment and stress states at both the final completed stage and during maximum cantilever conditions. The investigated parameters encompass concrete unit weight, elastic modulus, prestressing loss, concrete shrinkage and creep, and temperature. Coupling effects among critical parameters were analyzed, leading to the establishment of a construction monitoring system that incorporates coupled effects of key control parameters. Results indicate that temperature variations and prestressing loss exert significant influences on girder alignment and stress, whereas concrete elastic modulus and unit weight exhibit relatively minor effects. Consequently, parameters exerting substantial impacts on alignment and stress require priority in monitoring to guarantee successful closure during cantilever construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges have been widely used in bridge construction projects due to their advantages of structural stiffness, integrity, and cost-effectiveness1,2. To meet the demand for long-span structures and avoid affecting traffic beneath the bridge, these bridges are often constructed using the cantilever casting method3,4. However, during the cantilever casting of each segment of the main girder, due to various factors such as construction errors, material properties, and ambient temperature, there are often deviations between the actual and theoretical values of structural parameters, which seriously affect the geometric control and internal force state during bridge construction5,6,7,8,9. Therefore, during the construction of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges, it is necessary to closely monitor these factors and take effective measures for control and adjustment to ensure the quality and safety of the bridge construction.

In this regard, Wang and Dong10 found that changes in concrete unit weight and temperature gradients have the most significant impact on bridge deflection when studying the main parameters of cantilever casting construction control for continuous rigid frame bridges. Zhao et al.11, through studying the effects of construction control parameter changes on the maximum cantilever stage of prestressed continuous girder bridges, found that tensioning prestressed steel strands has a significant impact on the geometry and internal forces of the main girder during the maximum cantilever stage. Yang et al.12 analyzed the geometric variation rules of cantilever casting construction processes for three high-speed railway continuous girder bridges with different spans using simulation software, concluding that the mid-span of the bridges experiences upward deflection due to concrete shrinkage and creep. Wang et al.13 analyzed the cantilever construction process of cable-stayed bridges, establishing a finite element calculation program for geometric analysis during the installation process, and conducted detailed studies on the structural performance of bridge structures at different installation stages, providing necessary data for structural analysis and design. However, current research on the influence rules of cantilever casting construction control parameters on the geometry and stress of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges is still insufficient. To achieve precise construction control of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges, it is necessary to conduct an in-depth analysis of the sensitivity of construction control parameters.

Monitoring constitutes a critical requirement during cantilever casting construction. Throughout the cantilever casting process, structures undergo complex internal force redistribution and displacement variations. Consequently, implementing full-process monitoring and establishing a long-term monitoring assessment framework are paramount to ensuring structural integrity and construction safety14,15,16. The importance of monitoring is manifested in several aspects: firstly, it ensures project safety by real-time monitoring to detect potential safety hazards in construction and take timely measures to avoid accidents. Secondly, monitoring data can reflect construction quality, guide adjustments in construction techniques, and ensure project quality; Lastly, monitoring can also provide a basis for optimizing construction plans and improving construction efficiency17,18,19. Helmi et al.20 proposed a method for real-time remote monitoring of bridge deflection, which calculates bridge deflection by measuring the rotation and curvature of the bridge. The method was tested on two different highway bridges to analyze its feasibility. Additionally, he built a finite element model for further verification of the proposed method. Treacy and Brühwiler21 proposed a direct monitoring method for verifying the fatigue safety of construction joint details in existing post-tensioned concrete box girder bridges. The method uses direct, long-term monitoring to accurately determine actual effects caused by thermal and traffic influences, evaluate seasonal fatigue damage, and examine the effect of monitoring time on fatigue damage. However, current monitoring research lacks detailed analysis of the sensitivity of construction parameters to the geometry and stress of cantilever casting construction processes.

This paper uses finite element numerical analysis software to conduct an in-depth analysis of the sensitivity of construction control parameters of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges and the influence rules of parameter changes on the deflection and stress of the main girder. At the same time, it identifies key focus areas in the cantilever casting construction control of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges, and emphasizes the monitoring of sensitive parameters that significantly affect geometry and stress during cantilever casting construction, providing a reference for the construction of similar bridges.

This study conducts an in-depth sensitivity analysis of construction control parameters for prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges via finite element analysis, quantifying the influence patterns of parameter variations on girder deflection and stress. Concurrently, critical monitoring targets during cantilever casting control were identified, with coupling effects among key parameters analyzed. This led to the development of a construction monitoring system incorporating coupled effects of pivotal control parameters. During cantilever casting, high-sensitivity parameters significantly affecting geometric alignment and stress underwent prioritized monitoring, providing practical guidance for analogous bridge construction.

Project profile

The calculation span of the precast prestressed concrete continuous girder bridge on China’s Shenyang Metro Line 3 is (48 + 80 + 48) m, towering over an existing river bridge, and is constructed using the symmetrical cantilever casting method with hanging baskets. The main girder is 176 m long with a single-box single-cell variable section. The top width of the main girder is 10.4 m, the bottom width is 5.6 m, the flange length is 2.4 m, and the bottom slab varies according to a parabolic curve. The box girder height at the top of the main pier is 4.8 m, and the girder height for both the side spans and the middle span is 2.5 m. The segment 0 is 5 m long, segments 1–4 are 3.5 m long, segments 5–9 are 4 m long, the cast-in-place section of the side span is 7.0 m long, and the closure section of the middle span is 2 m long. The cantilever casting construction of the main girder uses C55 concrete. The lengths and weights of each segment of the bridge are shown in Table 1, and the overall layout of the bridge is shown in Fig. 1.

Establishment of finite element model

According to the construction plan and drawings, a finite element model was established. The model includes 58 beam elements and 67 nodes, and simulates the entire construction process of the prestressed concrete continuous girder bridge in accordance with the actual construction sequence. The simulation covers stages such as the advancement of the hanging basket, concrete pouring, tensioning of prestressed steel strands, side span closure, and middle span closure. During the cantilever casting construction, the girder is rigidly connected to the pier to form a fixed state. After closure, the temporary fixation is removed, and the pier and girder are converted to a pinned connection. The specific weight of the concrete is 26 kN/m3, and the elastic modulus of the concrete is 30 GPa. The tension control stress for the prestressed steel strands in the top and bottom plates of the side span closure section is 1339 MPa. The tension control stress for other longitudinal prestressed steel strands is 1302 MPa.

To better study the construction control parameters, a theoretical analysis of the cantilever casting construction process is conducted. The internal force relationship during the construction process is22:

\({\text{S}}_{{{\text{G}}1}}\) is the self-weight internal force of the main girder; \({\text{g}}(x)\) is the self-weight intensity of the main girder; \(y(x)\) is the coordinate of the corresponding influence line of the main girder internal force.

The deflection calculation for the structure during cantilever casting construction uses the conjugate beam method, establishing the relationship between the bending moment function.

\(M(x)\) of the actual beam and the load density function \(q(x)\) of the fictitious beam, based on the approximate differential equation of the beam deflection curve:

The bending moment function and load density function of the beam are:

Since the bending moment function \(M(x)\) of the actual beam is numerically equal to the load density function \(q(x)\) of the fictitious beam, for the same cross-section \(x\):

Thus, the deflection expression at any cross-section:

where \(f_{{\text{j}}}\) is the deflection at the point \(j\) of the cross-section; \(M_{{\text{i}}}\) is the average bending moment at the cross-section of the \(i\)-th segment; \(E_{{\text{i}}}\) is the elastic modulus of the concrete; \(I_{{\text{i}}}\) is the moment of inertia of the \(i\)-th segment; \(l_{{\text{i}}}\) is the length of the \(i\)-th segment; \(x_{{\text{j}}}\) is the distance from the deflection calculation point to the root of the fictitious beam; \(z_{{\text{i}}}\) is the distance from the center of gravity of the fictitious load of the \(i\)-th segment to the root of the fictitious beam.

Analysis of sensitive parameters of construction control

As the construction stage progresses, changes in multiple factors such as the construction techniques, construction duration, and construction environment of cantilever casting for continuous girder bridges significantly affect the bridge’s alignment and stress. Through parametric sensitivity analysis, the specific mechanisms by which these influencing factors during construction affect structural deformation and stress are thoroughly explored.

The influence of concrete bulk density

The self-weight of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges has a significant impact on the deflection and stress of the structure. During the actual cantilever construction process, errors inevitably occur due to factors such as the quality of the cast-in-place concrete and the selected operation tools, leading to changes in the concrete unit weight during construction and consequently affecting the self-weight of the structure. It is difficult to ensure that the actual unit weight of concrete is completely consistent with the designed value during the cantilever casting construction process. To analyze the impact of different concrete unit weight variations on the cantilever casting construction process of bridges, it is assumed that the concrete unit weight varies by ± 3% and ± 5%. A comparative analysis of the cumulative deflection difference and stress difference under two key states, namely, the completion of the bridge and the maximum cantilever during cantilever casting construction, is conducted. The comparison results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

According to Fig. 2, when the concrete unit weight changes, the cumulative deflection difference gradually increases during the segment-by-segment casting process of the main girder starting from block 0. As the concrete unit weight gradually increases, the deflection at the same location also increases accordingly. In the completed bridge state and the maximum cantilever state, the deflection change near block 0 is small, while the deflection difference near the closure sections of the side span and the mid-span is relatively large. When the unit weight variation is ± 5%, the maximum cumulative deflection difference during cantilever casting construction to the completed bridge state is 1.29 mm, and the maximum cumulative deflection difference during the maximum cantilever state is 1.10 mm. When the unit weight varies by ± 5%, the vertical deflection difference is approximately twice that when the unit weight varies by ± 3%.

According to Fig. 3, during the cantilever casting construction process, an increase in the concrete unit weight leads to a reduction in the top slab stress and an increase in the bottom slab stress of the main girder. When the cantilever casting construction is completed, a 5% increase in the concrete unit weight results in a maximum reduction of 0.40 MPa in the top slab stress and a maximum increase of 0.42 MPa in the bottom slab stress. During the maximum cantilever state of cantilever casting construction, as the concrete unit weight increases, the compressive stress at the top slab of each cross-section of the main girder decreases, while the compressive stress at the bottom slab increases. When the concrete unit weight increases by 5%, the maximum reduction in the top slab stress is 0.39 MPa, and the maximum increase in the bottom slab stress is 0.41 MPa. When the concrete unit weight decreases by 5%, the stress changes in the top and bottom slabs are opposite to those when the unit weight increases by 5%. When the concrete unit weight varies by ± 5%, the difference in stress between the top and bottom slabs is approximately twice that when the unit weight varies by ± 3%.

Influence of elastic modulus of concrete

During the cantilever casting construction process, there exists a certain deviation between the actual and design values of the concrete elastic modulus. Assuming a reduction in the concrete elastic modulus by 5%, 10%, and 15%, respectively, an analysis is conducted to examine the effects on the deflection and stress in both the maximum cantilever state and the completed bridge state during the cantilever casting construction process. The comparison results are shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

According to Fig. 4, the variation in the cumulative deflection difference of the main girder near the side span and mid-span is relatively significant with changes in the concrete elastic modulus. When the concrete elastic modulus decreases by 15%, the maximum deflection difference of the main girder near the mid-span is 0.94 mm in the completed bridge state and 0.21 mm in the cantilever state. According to Fig. 5, during the cantilever casting construction process, changes in the elastic modulus have a relatively minor impact on the stress. When the concrete elastic modulus decreases by 15%, the maximum stress difference at the bottom slab of the main girder section near the mid-span in the completed bridge state is 0.55 MPa; in the maximum cantilever state during the cantilever casting construction, the maximum stress difference at the top slab of the main girder section at the cantilever root is 0.30 MPa. Overall, the changes in the elastic modulus have a greater impact on the alignment and stress when construction reaches the completed bridge state compared to the maximum cantilever state.

Influence of prestress loss

Due to the influence of factors such as tensioning equipment, pipe friction, and prestressing tendon cross-sectional dimensions, there will be prestress losses during the cantilever casting process. Assuming prestress losses of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% during the cantilever casting construction process, an analysis is conducted to examine their impact on the cumulative deflection and stress during the construction to the maximum cantilever state and the completed bridge state.

According to Fig. 6, prestress losses have a significant impact on the deflection of the main girder, with the impact on deflection in the completed bridge state being more pronounced than in the maximum cantilever state. From the changes in the cumulative deflection difference at various locations of the main girder, the impact of prestress losses on deflection gradually increases as the construction progresses from the 0th block to the successive segments. Additionally, as the prestress losses increase, the deflection difference at the same location also correspondingly increases. During the cantilever casting construction process, prestress losses have a minor impact on the cumulative deflection near the 0th block, but have a significant impact on the cumulative deflection near the side span and mid-span closure segments. Specifically, when the prestress losses are 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, respectively, the maximum deflection changes near the mid-span closure segment in the completed bridge state are 1.63 mm, 3.28 mm, 4.98 mm, and 6.74 mm; in the maximum cantilever state, the corresponding changes are 0.94 mm, 1.88 mm, 2.85 mm, and 3.84 mm.

According to Fig. 7, in the completed bridge state, prestress losses have a significant impact on the stress at the cantilever root. Specifically, the compressive stress at the top slab of the main girder’s cantilever root decreases as prestress losses increase; when the prestress loss is 20%, the maximum reduction is 3.72 MPa. Additionally, the tensile stress at the bottom slab of the section increases as prestress losses increase; when the prestress loss is 20%, the maximum increase is 1.21 MPa. Near the side span and mid-span closure segments, prestress losses lead to a decrease in the compressive stress at the bottom slab; near the mid-span closure segment, when the prestress loss is 20%, the compressive stress at the bottom slab decreases by approximately 2.30 MPa. In the maximum cantilever state, the variation patterns of the top and bottom slab stresses are similar to those in the completed bridge state. Specifically, when the prestress loss is 20%, the maximum differences in stress at the top and bottom slabs of the cantilever root are 3.29 MPa and 0.73 MPa, respectively.

Influence of shrinkage and creep of concrete

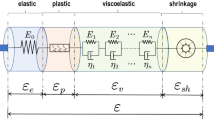

During the construction process, the shrinkage and creep of concrete initially increase rapidly, then gradually slow down, and eventually stabilize over the long term, significantly affecting the deformation of structural members23. The basic equation for the shrinkage and creep stress–strain relationship of concrete under constant stress is24:

During the cantilever casting construction process, the stresses on the cross-sections of the bridge structure continuously change. Under variable stress conditions, according to the linear creep theory and the principle of superposition, the above equation can be expressed as:

where \(\varphi (t,t_{0} )\) is the creep coefficient (with \(t_{0}\) and \(t\) being the loading age and the calculation age, respectively); \(E(t_{0} )\) is the elastic modulus of concrete at age \(t_{0}\); \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{sh}}}} (t,t_{0} )\) is the strain caused by concrete shrinkage; \(\Delta \sigma (t_{{\text{i}}} )\) is the stress increment at time \(t_{{\text{i}}}\).

Throughout the construction process, a comparative analysis is conducted considering both the effects of shrinkage and creep and ignoring them, as shown in Fig. 8. During the cantilever casting construction process, the cumulative deflection difference caused by concrete shrinkage and creep is significant near the mid-span closure segment, with a maximum difference of 2.40 mm. The stress differences at the top and bottom slabs of the main girder near the mid-span closure segment, caused by concrete shrinkage and creep, are 0.06 MPa and 0.20 MPa, respectively. Near the cantilever root, the stress differences at the top and bottom slabs of the main girder are 0.30 MPa and 0.03 MPa, respectively. Therefore, it is essential to consider the effects of shrinkage and creep in the design and construction of bridges.

The influence of concrete temperature change

In prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges, after a sudden change in temperature, due to the poor thermal conductivity of concrete, the internal temperature of the concrete structure lags behind, resulting in a temperature difference between the inside and outside, which causes deformation in the box girder structure25,26. Studies were conducted with temperature gradients of 5 °C, 10 °C, and 15 °C As shown in Fig. 9, when the temperature gradient is 15 °C, there is a noticeable sagging in the midspan of the main girder, with a maximum deflection change of 18.32 mm; near the side spans, there is a noticeable uplifting, with a maximum deflection change of 5.91 mm. As shown in Fig. 9, the stress difference at the top slab near the closure section is 4.62 MPa, and at the bottom slab, it is 7.37 MPa. Under the effect of temperature gradients, significant changes occur in the profile and stresses of the main girders; therefore, the impact of temperature on bridge structures must be given due attention during construction.

In the construction stages of maximum cantilever and completion, the sensitivity ranking of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges’ stresses and deflections to the aforementioned main construction control parameters is: prestress loss > concrete unit weight > elastic modulus. Therefore, during cantilever casting construction, it is crucial to strictly control the construction procedures and quality of in-situ cast concrete. Strictly control the stressing of prestressed strands at all stages of cantilever casting construction. Retension strands that have not been stressed to the required level to ensure proper stressing. During cantilever casting construction, concrete shrinkage and creep, as well as temperature changes, have significant effects on the bridge’s profile and stresses. Therefore, during construction, it is necessary to consider the effects of concrete shrinkage and creep and choose an appropriate temperature for bridge closure construction.

The worst-case scenarios for concrete unit weight, elastic modulus, prestress losses, concrete shrinkage and creep, and temperature changes during cantilever casting to bridge completion are illustrated in a pie chart shown in Fig. 10. As evident from Fig. 10a, temperature and prestress losses have the most significant impact on the bridge profile during cantilever casting construction, accounting for 62.57% and 22.19% respectively. The effects of concrete elastic modulus and concrete unit weight on the profile are relatively minor.

Figure 10b and c respectively illustrate the effects of parameter changes on the top and bottom slab stresses during cantilever casting construction. Temperature and prestress losses have the most significant impact on the stresses of the bridge during cantilever casting construction, accounting for 50.1% and 38.67%, respectively, while the effects of concrete elastic modulus and concrete unit weight on the profile are relatively minor. The overall pattern of bottom slab stresses is similar to that of top slab stresses, with bottom slab temperature stresses and prestress accounting for 67.93% and 21.38%, respectively.

Based on the comparison of calculation results, it is known that in the bridge completion stage, the main beam profile is most sensitive to temperature, followed by concrete unit weight and concrete shrinkage and creep. Overall temperature differences have the greatest impact on the main beam stresses, followed by prestress losses, concrete shrinkage and creep, and concrete unit weight. Therefore, tension-controlled prestress and temperature field changes are primary state parameters, and their control should be strengthened during construction. Parameters should be corrected in a timely manner based on measured elevations and stress feedback, and the bridge numerical analysis model should be updated accordingly.

Key parameter coupling effects analysis

During bridge construction, multi-parameter uncertainties may trigger extreme adverse scenarios. Traditional parametric analysis emphasizes variation patterns of individual parameters, whereas practical engineering prioritizes limit states arising from concurrent multi-hazard interactions. Hence, this section quantifies coupling effects via finite element analysis, considering: unit weight deviation (+ 5%), elastic modulus reduction (− 15%), prestress loss (20%), shrinkage-creep (included), and positive temperature gradient (+ 15 °C), revealing nonlinear interaction mechanisms among parameters to establish conservative early-warning thresholds for construction monitoring. Twelve load-case combinations were designed, with computational results for critical coupled-effect analyses presented in Table 2. Parameter combinations remained fixed per case. Response metrics include: maximum deflection difference (downward increment, mm); top-slab stress difference (compressive increase = positive, MPa); bottom-slab stress difference (compressive reduction = negative, MPa).

Regarding the parametric coupling effects, the deflection control factors are analyzed as follows: The coupling of temperature gradient (15 °C) and prestress loss (20%) dominates large deformations (Combination 12: 25.73 mm). Under their isolated coupling effect, the deflection increase is 22.63 mm (Combination 9). When superimposed with other adverse factors, the deflection difference amplifies, exacerbating their detrimental impact.

Top-slab stress control factors: High temperature gradient and bulk density increase induce significant compressive stress (Combination 11: + 5.13 MPa). Elastic modulus loss mitigates compressive stress growth (Combination 7: + 5.00 MPa).

Bottom-slab stress control factors: Prestress loss combined with temperature gradient causes a sharp reduction in compressive stress reserve (Combination 12: − 9.26 MPa). Bulk density increase (+ 5%) and elastic modulus variation accelerate this trend (Combination 2 → 12: − 8.96 → − 9.26 MPa).

Bidirectional effects of elastic modulus loss and shrinkage creep: (1) Top-slab stress relief: Stiffness reduction alleviates temperature-induced compressive stress (Combination 6 → 12: + 4.06 → + 3.76 MPa); (2) Bottom-slab stress: Tensile stress increases under identical conditions (Combination 6 → 12: − 9.21 → − 9.26 MPa) due to internal force redistribution caused by enhanced deformation. Offset phenomenon under extreme conditions: In the fully adverse parameter combination (Combination 12), shrinkage creep coupled with prestress/elastic modulus losses partially counteracts top-slab compressive stress (26.7% reduction vs. Combination 11). However, this represents the most critical comprehensive state (both deflection and bottom-slab stress peak).

Based on extreme response values, tiered warning thresholds are proposed: (1) Maximum deflection difference: ≥ 25.73 mm (Combination 12); (2) Maximum top-slab stress difference: ≥ 5.13 MPa (Combination 11); (3) Maximum bottom-slab stress difference: ≤ − 9.26 MPa (Combination 12). Risk assessment initiates when monitoring data approach 80% of maximum differences (e.g., deflection > 20.58 mm), with immediate work suspension upon threshold exceedance. Temperature gradient and prestress loss are primary triggers for deflection mutation, with their coupling exhibiting the dominant effect. The opposing impacts of elastic modulus loss on top/bottom-slab stresses reveal the dual-nature role of material stiffness in multi-parameter coupling. Although the extreme multi-parameter combination (Combination 12) does not simultaneously maximize all indices, it represents the highest comprehensive risk level, validating the engineering necessity of “most unfavorable scenario” design. The proposed warning thresholds establish conservative decision-making benchmarks for construction monitoring, emphasizing risk prevention during prestressing operations in high-temperature environments.

Construction supervision

The monitoring of the cantilever casting construction process is crucial for the successful construction of the bridge. Monitoring data is significant for adjusting the construction process and ensuring a smooth closure of the bridge. During the cantilever casting construction process, the box girders must be monitored in real-time to ensure that the control analysis provides accurate feedback. For the sensitivity factors mentioned in the previous chapters, especially those with significant impacts on bridge deflection and stress, such as temperature and prestress, these should be closely monitored during the construction process.

All monitoring data in this study were obtained from field measurements during the construction surveillance project for the elevated prestressed concrete continuous beam bridge on Shenyang Metro Line 3, China. Monitoring activities covered the entire process from cantilevered construction to bridge completion (October 2023 to August 2024).

As illustrated in Fig. 11, the construction monitoring system establishes a closed-loop dynamic control framework. Through iterative cycles of real-time monitoring, data analysis, state prediction, and construction adjustment, it ensures strict compliance of structural geometric alignment and stress states with design requirements during bridge construction. The core components comprise:

-

(1)

Construction monitoring measurements

Stress monitoring: Critical cross-section stresses of the main girder are continuously monitored to ensure structural integrity during construction.

Geometry monitoring: Elevation and axial alignment of all girder segments are precisely measured to control final bridge geometry.

Temperature monitoring: Ambient and structural temperature fields are recorded in real-time to quantify their significant impacts on geometric alignment and stresses, providing basis for analytical corrections.

Field testing: Concrete bulk density, elastic modulus, temporary construction loads, and form traveler deformations are measured to eliminate inherent discrepancies between theoretical models and actual structures.

-

(2)

Computational analysis for construction control

Parametric sensitivity analysis: Identifies dominant parameters (e.g., elastic modulus, bulk density, prestress loss, temperature gradient) affecting girder geometry and stresses, establishing prioritization for parameter calibration.

Parametric coupling analysis: Quantifies interactive effects among concrete shrinkage creep, prestress loss, and thermal loads to reveal comprehensive coupling mechanisms on structural responses.

Theoretical model error analysis: Evaluates inherent errors in computational models to precisely attribute deviations between measured and predicted values.

-

(3)

Dynamic parameter calibration and model updating

Multi-source data fusion: Dynamically updates material properties, boundary conditions, and loading parameters by integrating sensitivity rankings, quantified coupling effects, model error diagnostics, and field measurements.

Coupling effect incorporation: Embeds quantified parameter interactions into the calibration process, significantly improving model-to-reality fidelity.

-

(4)

Construction process simulation and state prediction

Utilizes the calibrated high-fidelity FEM to simulate subsequent construction stages, predicting geometric evolution and stress distributions under construction loads.

-

(5)

Closed-loop control implementation

Deviation adjustment: Compares predictions with design targets to compute required construction compensations.

Instruction generation: Outputs executable construction directives for subsequent segments to directly guide field operations.

Feedback mechanism: Establishes a complete closed-loop control cycle: Monitor → Analyze → Calibrate → Predict → Adjust → Construct → Re-monitor.

Measuring point arrangement

-

(1)

Displacement monitoring

The layout of cross-sectional and planar measurement points for profile monitoring is shown in Figs. 12 and 13, respectively. At the end of each beam segment, deformation monitoring points need to be arranged at three positions on the top slab of the concrete: left, middle, and right. These monitoring points use preformed steel bars, with a diameter no less than 14 mm, and should be welded to the main reinforcement of the bridge. After the concrete is poured, the steel bars should protrude about 5 cm from the surface, with the exposed part on the bridge surface painted with red paint.

-

(2)

Stress monitoring

The layout of stress measurement points and the arrangement of stress measurement sections for the entire bridge are shown in Figs. 14 and 15, respectively. The root of the cantilever and the closure section are selected as key stress monitoring sections. Stress sensors are arranged longitudinally along the bridge, with corresponding measurement points set on the top and bottom slabs of each section. Specifically, 3 monitoring sections are selected for the midspan, and 2 sections for each side span, totaling 7 monitoring sections for the entire bridge. Each section is equipped with 6 measurement points, totaling 42 stress measurement points for the entire bridge.

The stress monitoring process employs advanced vibrating wire sensors and automated data acquisition modules, enabling efficient remote monitoring. The specific monitoring process is as follows: First, the strain gauges are embedded and calibrated to ensure they accurately sense the strain changes in the structure. Next, the strain gauges are connected to the automated data acquisition system, which enables automatic collection and processing of the strain gauge data. Subsequently, the system collects temperature and strain data, which are then uploaded to the cloud server in real time. Finally, the remote monitoring and analysis of the structure’s stress are achieved using the device management features of the cloud platform. The embedding and calibration of the strain gauges and their connection to the automated detection system are shown in Figs. 16 and 17, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 18, the remote monitoring automated data acquisition module constitutes the core part of the stress monitoring system. The application of the automated data acquisition module significantly improves monitoring efficiency and data accuracy during stress monitoring. Its advantages are mainly reflected in the following aspects:

-

1.

Real-time monitoring: The automated data acquisition module can record stress data in real time, effectively avoiding the time lag and errors that may occur with manual measurements, helping to promptly detect stress anomalies during construction and providing timely basis for construction adjustments.

-

2.

High precision: The automated data acquisition module uses high-precision sensors and data processing technology, which can accurately record stress changes and reduce the influence of human factors on the data.

-

3.

Efficiency: It saves manpower and material resources, improves monitoring efficiency, and automatically stores and transmits data.

-

4.

Safety: It reduces the time personnel spend working in hazardous environments, thereby enhancing construction safety.

The entire stress monitoring process covers the embedding and calibration of strain gauges, the connection of the automated monitoring system, data collection and uploading, and the realization of remote stress monitoring, constituting a complete and efficient stress monitoring system.

Model validation and monitoring data analysis

Model verification

Comparison between numerical modeling results and field monitoring data (see figures below) demonstrates minor discrepancies. Figures 19 and 20 indicate good agreement between measured and theoretical values: Side-span and mid-span deviations range within 0–6 mm. Differential elevations at closure joints are maintained below 10 mm, well within geometric control tolerance limits. In stress comparison plots, construction stages 0–19 correspond to completion states of concrete pouring and prestressing for Blocks #1–#9. All numerical model validations against measured stresses show deviations controlled within ± 2 MPa. This verifies the deformation behavior of the long-span high-speed railway continuous girder, demonstrating sufficient model accuracy and engineering applicability.

Monitoring data analysis

-

(1)

Results of deformation monitoring

During the cantilever casting construction process, deformation of the bridge after each segment’s construction was monitored, focusing on temperature changes and the alignment and stress after prestressing, with construction errors shown in Figs. 21 and 22. In the Figs. 21 and 22, B represents the side span side, and Z represents the middle span side. The measured results show that the deviations of axis displacement and deflection are both controlled within 10 mm, and the relative deviation of the closure section is less than the specified 20 mm. Ultimately, the cantilever casting construction of the bridge was successfully completed, and the bridge alignment meets the design requirements.

-

(2)

Results of stress monitoring

The stress monitoring results show the stress at the root section of the cantilever, as depicted in Figs. 23 and 24, represented by the average values of three measuring points on the top and bottom slabs. During stress monitoring, real-time monitoring data of critical construction stages were focused on. Construction stages 0 through 19 represent the completion statuses of concrete pouring and prestressing of blocks 1# through 9#. The main girder of this bridge is made of C55 concrete, with its compressive and tensile stress norms being 24.85 MPa and 3.15 MPa, respectively. The monitoring results indicate that the stress values at each section are within the allowable range of construction control section stress, and the construction plan meets the design and normative requirements. The real stress at each measuring point is much less than the allowable stress of the concrete, and the structural stress state during construction is safe and reasonable.

The results of stress monitoring at different construction stages are shown in the following Figs:

Taking the temperature at the cantilever root measuring point as an example, Fig. 25 shows the temperature changes during the cantilever casting construction process. Solar radiation is the primary influencing factor, causing temperature fluctuations with a daily cycle. On the temperature time history curve, this change is manifested as regular upward and downward fluctuations, resembling “spikes,” reflecting the characteristics of short-term temperature changes. Further analysis indicates that the temperature changes of continuous beam bridges generally exhibit regularity with an annual cycle, indicating that temperature changes are influenced not only by sunlight but also by other long-term factors such as seasonal changes. Despite the short-term temperature fluctuations caused by solar radiation, the overall temperature performance of continuous beam bridges remains stable. The structural changes resulting therefrom, including deflection and stress changes, are all within reasonable limits and conform to relevant engineering requirements and standards. In summary, the temperature monitoring results during the cantilever casting construction process show that continuous beam bridges exhibit good adaptability and stability in both the construction process and bridge design, effectively coping with natural environmental changes.

Conclusion

With the aim of addressing the sensitivity of control parameters in the cantilever casting construction of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges, this study, based on the project of the prestressed concrete continuous girder bridge of the Shenyang Metro Overpass in China, employed finite element simulation for sensitivity analysis of the parameters, arriving at the following main conclusions:

-

1.

Comparative analysis reveals that all construction control parameters influence stresses and deformations in prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges under both final-completed and maximum-cantilever states. Parameter variations exhibit more pronounced effects on cumulative deflections and stress differentials in the final-completed state than in the maximum-cantilever state.

-

2.

During cantilever casting, bulk density, elastic modulus, shrinkage creep, prestress loss, and thermal variations collectively affect girder deflections and stresses. Prestress loss and thermal effects prove particularly critical. Consequently, construction protocols require: enhanced control of prestressing equipment, rigorous quality management of strand tensioning processes, and closure operations conducted within optimal temperature ranges.

-

3.

Multi-parameter extreme combination analysis identifies the critical scenario: peak deflection differential reaches 25.73 mm (Combination 12) with 9.26 MPa compressive stress loss at the bottom slab. Temperature-prestress loss synergy dominates structural responses, while elastic modulus loss exerts differential regulation effects on top/bottom-slab stresses.

-

4.

Guided by parametric sensitivity analysis, critical factors were prioritized during cantilever casting monitoring. Implementation of a sensitivity-integrated closed-loop control system (combining real-time stress/geometry/temperature monitoring with dynamic model calibration) confirmed that measured stresses at all instrumentation points remained substantially below code-permissible levels, validating structural safety throughout construction.

While this study uncovers sensitivity patterns of critical parameters, extending parametric sensitivity research to diverse bridge typologies remains imperative. Machine learning-based predictive models for parameter coupling effects should be developed to enhance quantification accuracy of multi-parameter interactions. Integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies will enable intelligent monitoring systems featuring real-time parameter calibration and bidirectional coordination between theoretical analysis and field monitoring.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ojha, S., Pal, P. & Mehta, P. K. Computational analysis of curved prestressed concrete box-girder bridges using finite element method. Sci. Rep. 15, 7050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91172-z (2025).

Li, S. et al. Three-dimensional nonlinear creep and shrinkage effects of a long-span prestressed concrete box girder bridge. Struct. Concr. 20, 638–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.201800148 (2019).

Biondini, F., Bontempi, F., Frangopol, D. M. & Malerba, P. G. Probabilistic service life assessment and maintenance planning of concrete structures. J. Struct. Eng. 132, 810–825. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-9445(2006)132:5(810) (2006).

Wen, Q.-J. Long-term effect analysis of prestressed concrete box-girder bridge widening. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 1580–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.09.041 (2011).

Ates, S. Numerical modelling of continuous concrete box girder bridges considering construction stages. Appl. Math. Model. 35, 3809–3820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2011.02.016 (2011).

Sampaio, A. Z. & Martins, O. P. The application of virtual reality technology in the construction of bridge: The cantilever and incremental launching methods. Autom. Constr. 37, 58–67 (2014).

Hu, F., Huang, P., Dong, F. & Blanchet, A. Stability safety assessment of long-span continuous girder bridges in cantilever construction. IFS 35, 4027–4035. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-169725 (2018).

Biondini, F. & Frangopol, D. M. Life-cycle performance of deteriorating structural systems under uncertainty: Review. J. Struct. Eng. 142, F4016001. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)st.1943-541x.0001544 (2016).

Liu, D. & Qi, T. Analysis of parameter sensitivity of construction control of multi span PC continuous beam bridge with corrugated steel webs. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 510, 052094. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/510/5/052094 (2020).

Wang, X. & Dong, J. Influence parameters of construction control of long-span bridge. Civ. Archit. Environ. Eng. 37(S2), 126–129 (2015).

Zhao, X. et al. Sensitivity analysis of structural parameters of PC girder bridge to mechanical properties of maximum cantilever structure. J. Highw. Transp. Sci. Technol. 28(11), 95–99 (2011).

Yang, Y. et al. Linear analysis research on cantilever construction of different spans continuous girder bridge for high-speed railway. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 13(08), 1549–1554 (2016).

Wang, P.-H., Tang, T.-Y. & Zheng, H.-N. Analysis of cable-stayed bridges during construction by cantilever methods. Comput. Struct. 82, 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2003.11.003 (2004).

Chiu, H.-S., Chern, J.-C. & Chang, K.-C. Long-term deflection control in cantilever prestressed concrete bridges. I: Control method. J. Eng. Mech. 122, 489–494. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(1996)122:6(489) (1996).

Yang, X.-M. et al. Structural health monitoring of long-span continuous girder bridge: System implementation and data analysis. Int. J. Str. Stab. Dyn. 25, 2550009. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455425500099 (2024).

Miao, S., Zhan, X., Yuan, Y. & Jia, L. A study of the mechanical properties of polyester fiber concrete continuous rigid frame bridge during construction. Buildings 13, 2849. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112849 (2023).

Tatangelo, M., Audisio, L., D’Amato, M., Gigliotti, R. & Braga, F. A new reliability-based procedure for life-cycle management of new and existing constructions. Structures 70, 107837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.107837 (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Asymmetric cantilever construction control of a U-shaped box concrete continuous bridge in complex environment. Buildings 13, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030591 (2023).

Gomez, H. C., Fanning, P. J., Feng, M. Q. & Lee, S. Testing and long-term monitoring of a curved concrete box girder bridge. Eng. Struct. 33, 2861–2869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2011.05.026 (2011).

Helmi, K., Taylor, T., Zarafshan, A. & Ansari, F. Reference free method for real time monitoring of bridge deflections. Eng. Struct. 103, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2015.09.002 (2015).

Treacy, M. A. & Brühwiler, E. A direct monitoring approach for the fatigue safety verification of construction joint details in an existing post-tensioned concrete box-girder bridge. Eng. Struct. 88, 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2015.01.036 (2015).

Dong, F., Shi, Z., Zhong, R. & Jin, N. FE model updating of continuous beam bridge based on response surface method. Buildings 14, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14040960 (2024).

Contento, A., Aloisio, A., Xue, J., He, J. & Briseghella, B. Ultra-high performance concrete beam-to-beam connections in continuous bridges: Experimental full-scale tests. FE Anal. Des. Eng. Struct. 316, 118594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118594 (2024).

Malm, R. & Sundquist, H. Time-dependent analyses of segmentally constructed balanced cantilever bridges. Eng. Struct. 32, 1038–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2009.12.030 (2010).

Song, X., Melhem, H., Li, J., Xu, Q. & Cheng, L. Effects of solar temperature gradient on long-span concrete box girder during cantilever construction. J. Bridge Eng. 21, 04015061. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)BE.1943-5592.0000844 (2016).

Huang, M., Zhang, J., Li, J. & Zhu, H. Temperature field characteristics of concrete box girders in rigid-frame bridges based on fine simulation and monitoring. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 72, 106265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2025.106265 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank China Construction Fifth Engineering Division Corp., Ltd for providing the funding and facilities to carry out the work presented in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by China State Construction Engineering Corporation Technology Research and Development Project, ZJKJ2023016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Haiqing Liu and Xiangen Gong; methodology, Haiqing Liu; validation, Ming Lei; formal analysis, Jinyang Zhang; investigation, Ming Lei; data curation, Liang Wang; writing original draft preparation, Jinyang Zhang; writing review and editing, Jinyang Zhang; visualization, Jinyang Zhang; supervision, Xiangen Gong. Software, Liang Wang; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Liu, H., Gong, X. et al. Sensitivity analysis and monitoring of control parameters in cantilever casting construction of prestressed concrete continuous girder bridges. Sci Rep 15, 29295 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14692-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14692-8