Abstract

In this study, total phenolic and flavonoid content, quantitative phenolic analysis, in-vivo, in-vitro and in-silico biological activities of Matricaria chamomilla flower extracts collected from Bulancak (Giresun) were investigated. Phenolic content was determined by LC–MS/MS and antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antigenotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities of the extract and the main components were investigated. Caffeic acid, quercetin and kaempferol were detected as major compounds in the flower extract by LC–MS/MS analysis and the detected levels were 165.085 mg/kg, 112.673 mg/kg and 67.417 mg/kg, respectively. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of M. chamomilla flower extract ranged from 12.4 to 81.1%, while superoxide anion inhibition was observed between 10.6 and 65.8%. Even at low doses, the main components, caffeic acid, quercetin and kaempferol, alone show more potent antioxidant activity. Flower extract was effective against both gram-positive, gram-negative bacteria and fungi and exhibited a broad spectrum antimicrobial effect. Three main components showed a lower sidal effect than the flower extract. M. chamomilla flower extract showed significant antigenotoxicity by reducing NaN3-induced micronucleus formation by 58%, while the main components showed a lower activity. M. chamomilla flower extract, showed a protein denaturation inhibition in the range of 23.5% to 71% and its IC50 value was 408 µg/mL. The IC50 values of caffeic acid, quercetin and kaempferol, which are the main components of flower extract, were calculated as 306 µg/mL, 283 µg/mL and 333 µg/mL, respectively in anti-inflamatory test. The interactions of main components of M. chamomilla flower extract and GABAA receptor was investigated by in-silico molecular docking method. The interaction of caffeic acid, one of the main components detected in the extract, with GABAA was predominantly through hydrogen bonding and the binding energy of this interaction was − 5.01 kcal/mol. In the interaction between gentisic acid and GABAA, an inhibition constant of 351.67 µM was determined. The binding energies obtained in the kaempferol and quercetin interactions were − 5.47 kcal/mol and − 4.41 kcal/mol, respectively. The low/medium binding energies observed for the tested active ingredients indicate that other constituents in M. chamomilla flowers might exert stronger GABAA inhibition than the compounds evaluated. Additionally, weaker binding typically results in reversible interactions, which can be advantageous in certain therapeutic strategies. As a result, this study provides significant contributions to scientific knowledge in terms of reflecting regional diversity in the biological effects of M. chamomilla flower, comparative analysis of extracts and pure components, investigation of antigenotoxic activity on a component basis, and obtaining mechanistic evidence on sedative effect potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medicinal plants have historically proven their value as a rich source of biomolecules with therapeutic potential, and they still today constitute an important pool for the identification of new drugs1. Matricaria chamomilla L. (chamomile) has been the subject of extensive research in the scientific literature concerning its excellent medicinal properties. This plant is a cold-tolerant annual herb that grows in all soil types. M. chamomilla is native to Southern and Eastern Europe, Northern and Western Asia and is now widely distributed throughout the world2. Based on herbarium and field studies, different species of Matricaria such as M. aurea, M. chamomilla var. chamomilla, M. chamomilla var. recutita and M. matricarioides have been described in the flora of Türkiye. The stems of M. chamomilla described from Türkiye are 10–50 cm tall, glabrous or sparsely pubescent; leaves are 2–3-pinnatisect with narrow terminal segments. The lower leaves are 5–7 cm long and glabrous, but sometimes hairy. Primary segments of leaves 9–12 pairs; capitula usually solitary, sometimes corymbose/subcorymbose with short/long peduncles. Flowers 10–20 mm long and yellow with 5 lobes. Achenes are very small, 0.7–1.05 mm long, 0.25–0.4 mm wide, coronate/echoronate, brown and mucilaginous. The wide geographical distribution and habitat diversity of M. chamomilla, such as degraded grasslands, vacant lots, areas along highways and railways, waste and dry areas, indicate its different adaptability to different environments3,4. M. chamomilla, which has various biological activities, has a rich phytochemical content. The presence of bisabolol and its derivatives, bisabolone oxide A, chamazulene and β-farnesene has been reported in M. chamomilla, which is reported to contain more than 200 essential oil species; it has also been reported that these contents are affected by geographical region, environment and genetic factors5. The ratio and type of essential oils in M. chamomilla vary according to the part of the plant, the environment in which it grows and the extraction method. A total of 24 different essential oils were determined in M. chamomilla, which is distributed in Morocco and obtained by microwave-assisted hydrodistillation, and chamazulene (26.11%), cis-β-farnesene (11.64%) and eucalyptol (8.19%) were determined as the main components6. Abbas et al.7 determined the presence of α-bisabolol oxide A (33–50.5%) in the essential oils investigated in fresh and dried M. chamomilla flowers using different techniques. El-Hefny et al.8 reported the presence of cis-β-farnesene (27%) as the main component, followed by D-limonene (15.25%) and α-bisabolol oxide A (14.9%) in samples collected from Egypt. M. chamomilla flower and leaf parts contain large amounts of flavonoids and phenolic substances. Ghoniem et al.9 reported the presence of myricetin, quercetin, naringenin flavonoids; benzoic acid and rosmarinic acid in samples collected from Giza. Petrul’ová-Poracká et al.10 reported the presence of coumarins (umbelliferone-7-O-_-d-glucoside), daphnin and daphnetin (7,8-dihydroxycoumarin) in extracts of M. chamomilla grown in Slovakia.

M. chamomilla has been shown to exhibit several biological and pharmacological properties that can be attributed to the presence of different phytochemicals in the plant. Quercetin and caffeic acid present in M. chamomilla flower extracts are potent antibacterial agents11. Al-Ismail and Talal12 reported that 41.6 g/L M. chamomilla extract has antimicrobial activity, Rahman and Chandra13 reported that M. chamomilla gel has antibacterial activity against Enterococcus faecalis with an inhibitory zone of 20.62 mm. El-Hefny et al.8 found that the antifungal activity of M. chamomilla phytochemicals was dose-dependent and the best results were obtained against A. niger. M. chamomilla extracts and essential oils were found to have the capacity to inhibit the growth of a wide range of parasites and insects. It was found that M. chamomilla essential oils distributed in Tunisia exhibited a significant lethal effect on Leishmania amazonensis and Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum promastigotes, with IC50 values in the range of 10.4–10.8 µg/mL14. It has also been determined that apigenin, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, cis and trans-2-hydroxy-4-methoxycinnamic acid glucosides components of M. chamomilla exhibit antidiabetic activity by inhibiting amylase and maltase enzymes involved in carbohydrate digestion, restricting sucrose and glucose transport and regulating sugar absorption15. Although many literature studies have shown that M. chamomilla teas and extracts improve sleep quality and alleviate depression and anxiety, the mechanism is still not fully understood. Kupfersztain et al.16 found that 12-week use of an herbal extract containing chamomile alleviated sleep disturbances and fatigue more than placebo. Zick et al.17 reported that a four-week treatment with M. chamomilla extract had moderate effects on sleep problems and or night-time awakenings.

A plethora of studies have been conducted in the scientific literature investigating the pharmacological and biological activities of plants18,19,20,21. Furthermore, numerous studies have been undertaken in which phytochemical contents are associated with activity. Secondary metabolites play an important role in the formation of biological activity. The production, type and level of secondary metabolites are influenced by many factors including the geographical conditions of the plant. For this reason, it is very important to determine and compare the phytochemical contents and biological activities of plants belonging to the same species distributed in different regions and to reveal the differences. In this study, total phenolic and flavonoid content, quantitative phenolic analysis, in-vivo, in-vitro and in-silico biological activities of M. chamomilla flower extracts collected from Bulancak (Giresun-Türkiye) were investigated. Quantitative phenolic profile was determined by LC–MS/MS analysis. Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, antigenotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities of M. chamomilla flower extract and the main components were investigated. In this way, the biological activities of the main components and the flower extract were investigated separately and a detailed comparison was made. M. chamomilla, known for its calming and sedative properties, also has sleep-enhancing effects, but evidence-based findings of this activity are insufficient. In this context, the interaction of the main active compounds with gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptor (GABAA) was examined in the evaluation of the calming effect of M. chamomilla and in-silico molecular docking analysis was used for this purpose.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation and extraction

M. chamomilla were collected from Bulancak-Giresun (Türkiye) on 21.05.2023 and the flower parts were carefully separated and dried. M. chamomilla generally blooms between late spring and early summer. In Türkiye, this period is observed between May and June. Therefore, the flower harvest was determined to be in May. Sampling was conducted at a single location, maintaining consistent environmental conditions such as soil type, altitude, light, and humidity. Collected samples were combined to ensure homogeneity. The identification of M. chamomilla was carried out at the Botany Department of Giresun University by Prof. Zafer TURKMEN. One specimen with voucher number BIO-M.cha/2023 was deposited in the herbarium of the Department of Biology. Experimental research on plant samples, including the supply of plant material, complies with institutional, national and international guidelines and legislation. M. chamomilla flower samples were dried in an oven at 35 °C and ground in a mill. 200 g of ground flower samples were extracted by maceration method using different solvents including water, ethanol, chloroform and hexane (500 mL). After extraction in a shaking incubator for 24 h, the solvent phase was filtered with Whatman No:4 filter paper22. The filtrate was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was evaporated. The residues obtained at the end of evaporation were collected and used for the determination of biological activity and the efficiency of the extraction was determined by calculating the percentage of the ratio of extract/plant.

Phytochemical analysis

The total flavonoid content in M. chamomilla extract was determined by spectrophotometric method. 1 mL of 5% sodium nitrite was added to 10 mL of extract and incubated for 6 min. Following this, 1 mL of 10% aluminium nitrate was added to the mixture. Following a second incubation, 10 mL of NaOH was added to the mixture, and the total volume was completed to 25 mL with dH2O. Following a 15-min incubation period, the solution’s absorbancy was measured at a wavelength of 510 nm. Quercetin (QE) was utilised as the standard substance, and the results were expressed as mgQE/g23. The total phenolic content of M. chamomilla extract was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteau method. For this purpose, a mixture containing 10 µL of the extract, 40 µL of Folin reagent, 10 µL of H2O and 200 µL of 10% Na2CO3 was prepared and incubated for 30 min. Subsequent to this, the optical density of the solution was measured at a wavelength of 725 nm. The total phenol content was then expressed in terms of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) in milligrams per gram24. Quantitative phenolic compounds of M. chamomilla were determined by LC–MS/MS analysis. For this purpose, 1 g of plant sample was extracted in methanol-dichloromethane, filtered through a syringe filter (0.45 µm) and analyzed. The detailed information about analysis profile is given in Supplamentary material25. LC–MS/MS analysis was performed at Hitit University HUBTUAM. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Biological activity

Biological activity analyses were carried out with the ethanol extract. Ethanol extract was selected for further biological and phytochemical analyses, as it provided the highest yield of phenolic and flavonoid compounds, which are known to contribute to antioxidant and antigenotoxic activities. Additionally, the choice of ethanol aligns with safety considerations for biological testing and better extraction efficiency for polar and semi-polar bioactive compounds. Antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antigenotoxic and anti-inflamatory activities were investigated as biological activities. The biological activities of caffeic acid, quercetin, kaempferol were also analyzed separately and the potential synergistic/antagonistic interactions were evaluated by comparing with the extract activity. Caffeic acid (CAS: 331-39-5, ≥ 98.0%, HPLC grade), quercetin (CAS: 117-39-5, ≥ 95.0%, HPLC grade) and kaempferol (CAS:520-18-3, ≥ 97.0%, HPLC grade) were supplied from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis MO, USA). The interactions of the main components with the GABAA receptor were also studied by in-silico molecular docking to evaluate the sedative/sleep-regulating effect.

Antioxidant activity

To determine the antioxidant activity of M. chamomilla flower extract and the main three components, DPPH and superoxide anion scavenging activities were investigated. For DPPH test, 80 μL sample of the extract or main components prepared at different concentrations was mixed with 1185 μL DPPH (6 × 10–5 M). The mixture was kept in the dark for 60 min and the absorbance of the solution was determined spectrophotometrically at 517 nm. For superoxide anion scavenging activity, a mixture containing 50 mM phosphate buffer, 20 μg riboflavin, 12 mM EDTA and 0.1 mg/3 mL NBT was prepared. Samples prepared at different concentrations (extract or main component) were added to the mixture and exposed to fluorescent lamp illumination for 90 s. After incubation, the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 590 nm. BHT was used as standard substance and DPPH and superoxide radical scavenging activities were calculated as % inhibition by using Eq. (1).

Antibacterial and antifungal activity

Antimicrobial activity was tested against bacterial and fungal species by disk diffusion method and broth microdilution technique. The antimicrobial activity of the extract and the main components were tested against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC9027, Salmonella enteritidis ATCC13076, Bacillus subtilis IMG22, Bacillus cereus ATCC14579, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 bacteria species and Candida tropicalis ATCC13803 and Candida albicans ATCC90028 fungal species. Bacterial cultures were prepared in Mueller Hinton Broth medium at 37 °C for 48 h. Fungal cultures were prepared after incubation in Potato Dextrose Broth medium for 48 h. For the determination of antibacterial activity, samples of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (108 cells/mL) were inoculated homogeneously on Mueller Hinton Agar petri plates. Antifungal activity was determined by inoculating fungal species (106 CFU/mL) homogeneously onto Sabouraud maltose agar petri plates. Empty sterile disks (6 mm) were placed on the surfaces of all media. A quantity of 20 µL of M. chamomilla extract or main components (caffeic acid, quercetin, kaempferol) was transferred to the disks. Petri dishes were kept at 4 °C for 1 h and incubated at 37 °C for bacteria and 27 °C for fungi for 24 h. The inhibition zones formed on the medium after incubation were measured in millimetres. The standard antibiotics used were Nystatin and Amikacin. The method suggested by Üst et al.24 was used to determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) with broth microdilution technique. MIC indicates the lowest concentration required to inhibit bacterial growth, while MBC indicates the lowest concentration required to kill bacteria. All antimicrobial tests were repeated three times.

Antigenotoxic activity with Allium test

The antigenotoxic activities of M. chamomilla flower extract and the main components were determined using the Allium test. The Allium test is a simple and reliable test in which both genotoxic effects and antigenotoxic activities can be determined26,27,28,29. Initially, the Allium bulbs were divided into six distinct groups. In each group, 10 Allium bulbs were utilised, and chromosomal abnormalities (CAs) were determined in the roots obtained after 72 h of germination. In negative control, and the bulbs were germinated with distilled water. In positive control group, the bulbs were treated with sodium azide (20 mg/L NaN3), a potent mutagen. NaN3 is a potent mutagen that has been shown to induce high rates of CAs. In the treatment groups, M. chamomilla extract and main components were administered together with NaN3 (at the same dose as the positive mutagen). Antigenotoxic effect was determined by examining the decrease in CAs induced by positive mutagen. CAs determination was achieved through the collection of root tip samples from each bulb at the end of the germination period, followed by the preparation of fixed preparations. 1 cm long root tips were fixed with Clarke’s solution and passed through an ethanol series. For the hydrolysis stage, the samples were subjected to an initial 17-min incubation in 1N HCl at 60 °C, followed by a 30-min incubation in 45% acetic acid. Finally, the cells were stained with acetocarmine for 24 h and examined under a research microscope30,31. The calculation of CAs formation and antigenotoxic activity was performed utilising Eqs. (2, 3), respectively.

A: total cells with abnormal chromosomes, B: total counted cells, a: CA% of NaN3 treated group, b: CA% of plant extract + NaN3 treated group, c: CA% of control group.

Anti-inflammatory activity

Anti-inflammatory activity was determined using the serum albumin protein denaturation stabilization assay, as described by Kedi et al.32. A mixture containing 500 μL of BSA (1% w/v), 1.4 mL of phosphate buffer and 500 μL of extract or main component at different concentrations (50–600 µg/mL) was prepared. Following this, the mixture was heated at 57 °C for 20 min, absorbance was then measured at 660 nm using a microplate reader. Aspirin was used as the positive control, while a plant extract/main component-free buffer was used as the negative control. The percent inhibition of protein denaturation was determined by Eq. (4).

where, Abse,p is the absorbance of extract/positive agent/main component and Absc is the absorbance of the negative control. IC50 values were calculated using a scatter plot of concentrations (x-axis) plotted against percent inhibition (y-axis).

In-silico receptor interactions

In-silico interactions are a frequently preferred method to elucidate the mechanism of action of many active compounds33,34,35. The effects of M. chamomilla on sleep are thought to be due to its binding to benzodiazepine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptors, which have hypnotic effects on sleep–wake cycles. Therefore, the inhibition of GABAA receptor was investigated by in-silico molecular docking method. Caffeic acid (PubChem ID:689043), gentisic acid (PubChem ID:3469), kaempferol (PubChem ID:5280863) and quercetin (PubChem ID:5280343), which are major components in M. chamomilla flower extract, were obtained from pubchem36. Receptor data were obtained from the Protein Data Bank37. GABAa (PDB ID:9CRS)38 data were loaded into Maestro BioLuminate 5.039 and structural deficiencies and missing hydrogen atoms were found and removed. The chemical compounds and GABAa data were then interacted with AutoDock Vina version 4.2.640 and visualized using Biovia Discovery Studio 2020 Client41.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were conducted utilising the IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software program, and the resulting data were presented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). Statistical significance between means was determined by Duncan’s test and One-way ANOVA, with a p value of less than 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results and discusssion

Extraction efficiency and phytochemical characterization

In the extraction of M. chamomilla using water, ethanol, chloroform and hexane, the highest efficiency was obtained with ethanol extraction. The performance order of the solvents in terms of extraction efficiency was ethanol (9.5%) > hexane (8.6%) > chloroform (7.8%) > water (5.11%). The highest total phenol content was obtained in ethanol extract and was determined as 11.6 mgGAE/g. Total flavonoid content in the extracts was lower than phenolic content and was determined as 9.6 mgQE/g in the ethanol extract. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids are of significant value in relation to their antioxidant properties. These metabolites, which contain at least one hydroxyl group in their structure, have a plethora of biological effects, including antioxidant, anticancer, antibacterial, cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antifungal properties24,42. A plethora of studies have been conducted on the phenolic and flavonoid content of M. chamomilla flowers. Roby et al.43 reported a phenolic content level of 3.7–2.4 GAE mg/g phenolic content in M. chamomilla flowers, determining that the amount of flavonoids was higher than phenolics. Literature studies show the differences in the levels of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. These differences can be attributed to changes in the levels of secondary metabolites that occur during the adaptation of the plant to its specific growing environment.

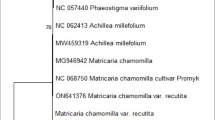

As a result of LC–MS/MS analysis of M. chamomilla flowers, 29 standard phenolic compounds were tested and the presence of 17 compounds among these standards was determined. Caffeic acid was detected in the flower extract in a major proportion and its presence rate was determined as 165.085 mg/kg. Following caffeic acid, quercetin was detected in a major proportion and its presence rate was 112.673 mg/kg. The third compound among phenolics, kaempferol, was detected at a level of 67.417 mg/kg. Apart from these three major compounds, protecatechuic acid, gentisic acid, taxifolin, rutin are phenolics detected in the range of 10–15 mg/kg. Below 10 mg/kg, sesamol, catechin, vannilin, syringic acid, syringic aldehyde, p_coumaric acid, salicylic acid, 4-OH benzoic acid, rosmarinic acid and naringenin were detected and these structures were defined as minor components (Fig. 1). Amount of phenolics, retention times (Rt), limit of detection (LOD), Limit of quantification (LOQ) and percentage recovery values (RSD%) for the standards were given in Table 1. Each compound detected in LC–MS/MS analysis has different biological activities and as a cumulative result of these activities, M. chamomilla flowers exhibits a rich activity profile. It is thought that caffeic acid, the first major compound detected in M. chamomilla flower, contributes highly to biological activity due to its high content. In-vitro and in-vivo experiments have been carried out proving numerous physiological effects of caffeic acid and its derivatives such as antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory activities. Recent studies have also reported anti-atherosclerotic, immunostimulatory, antidiabetic, cardioprotective, antiproliferative, hepatoprotective, anticarcinogenic and anti-hepatocellular carcinoma activities44. The anti-carcinogenic effect of caffeic acid is mainly related to its antioxidant capacities. Elimination of free radicals and inhibition of free radical production as well as induction of DNA oxidation in cancer cells are important anticarcinogenic mechanisms of action of caffeic acid45,46. Quercetin, a bioactive molecule found in M. chamomilla flower, has been the subject of extensive research due to its various pharmacological activities such as antioxidant, antiviral, immunomodulatory and anticancer activity with a low toxicity profile47. It has been demonstrated that quercetin exerts its anticancer effects by modulating antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress factors. Indeed, studies have shown that this bioflavonoid can prevent the progression of various cancers, including those affecting the liver, lung, colon, prostate, cervix and breast48. Quercetin has also shown potent bacteriostatic effects against several bacterial species, and has been shown to be more effective against Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative bacteria49. Kaempferol detected in M. chamomilla flower at the rate of 67.417 mg/kg has anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, anti-adipogenic, hepatoprotective, cytoprotective, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. The presence of double bond at C2-C3 and hydroxyl groups at C3, C5 and C4 in the structure of kaempferol is very important in the formation of its antioxidant activity50. The ability of kaempferol to reduce superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical and peroxynitrite levels even at submicromolar concentrations indicates the strength of its antioxidant activity. Along with these three major components identified in the structure of M. chamomilla flower, other components such as gallic acid, protecatechuic acid, epicatechin, sesamol, catechin, vannilin, syringic acid, syringic aldehyde, p_coumaric acid, salicylic acid and rosmarinic acid provide strong biological effects51. In the literature, there are studies investigating the phenolic content of M. chamomilla extracts from different regions. As reported by Haghi et al.52, a range of compounds were identified in Matricaria chamomilla collected from the Kashan region, including chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, salicylic acid, apigenin-7-glucoside, quercetin, rutin, caffeic acid, luteolin and kaempferol. De Angelis et al.53 found that M. chamomilla flowers from Italy contained hydroxycinnamic acids, flavones and flavonols.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activities of M. chamomilla extract and its three main components, caffeic acid, quercetin, kaempferol, were examined by DPPH and superoxide anion scavenging tests and the results are given in Fig. 2. DPPH scavenging activity of M. chamomilla extract was determined in the range of 12.4–81.1% and IC50 value was determined as 45 mg/mL. Inhibition of superoxide anion was observed in the range of 10.6–65.8% and IC50 value was determined as 150 mg/mL. For both radicals, higher scavenging activity and lower IC50 value were obtained with BHT used as standard antioxidant. These results indicate a higher antioxidant effect of BHT compared to M. chamomilla extract. BHT is a widely used synthetic antioxidant, but its reported harmful effects on the human body limit the use of BHT. From this point of view, it can be said that M. chamomilla extract is a potentially safer alternative antioxidant source. This effect of M. chamomilla is closely related to the phenolic compounds. Phenolic substances are powerful antioxidant molecules and show these effects especially by neutralizing radicals54,55,56,57. In the literature, there are studies investigating the antioxidant activity of M. chamomilla extracts obtained from different regions by radical scavenging tests. Al-Dabbagh et al.58 reported that M. chamomilla obtained from the UAE exhibited DPPH scavenging activity in the range of 84.2%-94.8%. Stanojevic et al.59 reported IC50 values of oils obtained from M. chamomilla flowers collected from Prijedor was 3.32–2.07 mg/mL for DPPH. Roby et al.43 reported that essential oils isolated from M. chamomilla exhibited IC50 values of 0.0022 to 0.0041 mmol. Within the scope of the study, the radical scavenging activities of three major components detected in the extract were examined seperately and high activities were obtained compared to the extract. Among the main components, the highest activity was observed with quercetin and the DPPH and superoxide anion scavenging activities of this component were determined as 75.9% and 68.7% at 40 µg/mL dose, respectively. At the same dose, the DPPH scavenging activities of caffeic acid and kaempferol were 50.3% and 41.3%, respectively. These results suggest that the main components alone exhibit a more effective antioxidant activity even at low doses.

The possible reason for the lower activity obtained with the extract could be the antagonistic interaction between the three main components and the other components in the extract. The lower activity of the extract suggests antagonism; however, to definitively assess an antagonistic interaction, it is necessary to conduct similar studies with different combinations of ingredients. The antagonistic effects may be observed through a variety of mechanisms. These mechanisms encompass a range of phenomena, including competition between two compounds for binding to the same target site, reactions and inactivation of both compounds, opposing effects on the same target, and pro-oxidant properties. One of the possible reasons for the lower antioxidant activity of the extract in the present study may be this kind of interference. A plethora of studies have been conducted which demonstrate the antagonistic effects of herbal ingredients60. Joshi et al.61 reported that the active compounds in plants exhibited low radical scavenging activities as a result of the antagonistic effect of their active compounds, and kaempferol reported weaker DPPH scavenging activity in the presence of resveratrol, indicating statistical antagonism.

Antibacterial and antifungal activity

The antimicrobial activity of M. chamomilla flower extract and three main components were determined by disk diffusion and broth dilution methods and the inhibition zones are given in Fig. 3. Antimicrobial activity was tested against gram positive, gram negative bacteria and fungi species. Inhibition zones in the range of 15.9–17.3 mm were obtained against gram positive bacteria. The highest inhibition zone was obtained against B. cereus with a zone diameter of 17.3 ± 0.4 mm. Amikacin used as standard showed an activity in the range of 18.6–19.2 mm against the tested gram positive bacteria. The inhibition zones of gram-negatives were found to be lower than gram-positive. M. chamomilla flower extract produced inhibition zones of 12.8 mm, 14.3 mm and 15.4 mm against E. coli, S. enteritidis and P. aeruginosa, respectively. Amikacin used as a standard showed an activity in the range of 17–17.1 mm against the tested gram negative bacteria. These results showed that the flower extract was effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and exhibited broad spectrum properties. The extract showed a higher effect in gram positive compared to gram negative and a statistical difference was observed (p < 0.05). The selectivity of the extract is due to the structural difference between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The lipid cell membrane in gram-negative bacteria provides partial resistance to antimicrobial agents62. The antifungal activity of M. chamomilla flower extract is lower compared to its antibacterial activity. An inhibition zone of 12.8 ± 0.3 mm was formed against C. tropicalis and 17.3 ± 0.5 mm against C. albicans. Inhibition zones of nystatin used as a standard are in the range of 17.3–18.4. The lower inhibition zones detected in fungi compared to bacteria are related to structural differences. The cell wall of fungi, especially rich in chitin and ergosterol, is an important cause of resistance. The increase in chitin levels in the presence of antimicrobial agents indicates that chitin is an important factor in the development of cell wall resistance63. There are also studies reporting the antimicrobial activity of M. chamomilla extracts in the literature. Kameri et al.64 reported that M. chamomilla extract collected from Kosovo exhibited an inhibition zone of 9.7 mm against Enterococcus faecalis. Boudieb et al.65 found that M. chamomilla extract, which is distributed in Nigeria, showed very strong sidal effect against Pseudomonas sp. and formed 22.5 mm inhibition zone. Osman et al.66 determined the antifungal activity of M. chamomilla obtained in Egypt by disk diffusion and obtained inhibition zones in the range of 10–12 mm against Aspergillus niger and 7–12 mm against Penicillium citrinum.

The broad spectrum antimicrobial activity of M. chamomilla can be explained by the active components it contains. Phenolic compounds detected by LC–MS/MS analysis have an important effect on the emergence of antimicrobial activity. Caffeic acid and quercetin, which were detected as major compounds in LC–MS/MS analysis, show sidal effect by causing deformations and leaks in bacterial cell membrane. P-coumaric acid detected at 8.986 mg/kg increases membrane permeability in bacteria and causes leakage of cytoplasmic contents. It also has genotoxic effect on bacteria and exhibits bactericidal activity by causing intercalation with DNA double helix67. Minor compounds in the extract strengthen the antibacterial effect as well as major compounds. Vanillin, which is detected at a minor rate in the extract, causes disruptions in intracellular pH balance, disruptions in bacterial membrane integrity, and leakage of ions inside the cell68. The antimicrobial activity results of the main components alone are also given in Fig. 3. Three main components showed a lower sidal effect than the flower extract. Caffeic acid alone showed the highest antimicrobial activity against S. aureus with a zone of inhibition of 9.7 mm, while the zone of inhibition of the flower extract on this bacterium was 16.7 mm. Quercetin showed the highest antimicrobial activity against P. aureginosa, but this effect was 47.4% lower compared to the flower extract. Kaempferol showed the highest effect against S. enteritidis with an inhibition zone of 7.2 mm, whereas the flower extract produced an inhibition zone of 16.7 mm against this bacteria. The zones of inhibition formed by the main components were statistically significantly lower compared to the extract (p < 0.05). In addition to the inhibition zones of the extract and main components, MIC and MBC values were also investigated by broth microdilution method. In accordance with the inhibition zones, MIC and MBC values of the extract were obtained at lower levels compared to the main components, i.e., the antimicrobial effect was stronger. MIC and MBC values of the flower extract against Gram negatives were determined between 625–700 µg/mL and 675–725 µg/mL, respectively. These values were determined between 575–650 µg/mL and 625–675 µg/mL for Gram positives, respectively. Higher MIC and MBC values were obtained for the main components, caffeic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol. MBC values against all tested microorganisms were obtained in the range of 825–1000 µg/mL for caffeic acid, 700–975 µg/mL for quercetin and 925–1150 µg/mL for kaempferol. In general, the MIC and MBC values of the flower extract are lower than the values of the main components alone, indicating that the flower extract is more effective and that a stronger cidal effect occurs with the cumulative effect of all components in the extract. The strengthening of antimicrobial activity with the cumulative effect of the components contained in the plant extract can be explained by several mechanisms. The most important of these mechanisms is the multiple effect mechanism. The activity of the extract may be strengthened as a result of the simultaneous action of different components on different targets. Some of the phytochemicals in the extract (especially terpenoids) increase bacterial membrane permeability and facilitate the entry of antimicrobial substances into the cell. Inhibition of efflux pumps, inhibition of biofilm formation and breaking antimicrobial resistance by plant components may also potentiate the effect of the extract. The higher antimicrobial activity of the extract than the main components in this study may be attributed to these multiple mechanisms of action. Although the antimicrobial activity of extract was found to be higher compared to the main components tested, further studies using combination analyses are needed to confirm synergistic interactions between the components of the extract60. In the literature, there are studies reporting the synergistic effects of phytochemicals contained in plant extracts. Abu-Hussien et al.69 reported that phytochemicals in plant extracts showed synergistic effect against S. aureus when applied together and a stronger sidal effect emerged. De Oliveira et al.70 reported that phenolic substances in plants show antimicrobial synergy and especially cinnamic acid exhibited a strong activity against Salmonella typhimurium in combination with other phytochemicals.

Antigenotoxic activity

The antigenotoxic activities of the M. chamomilla flower extract and the main components are given in Table 2 and Fig. 4. Antigenotoxic activity was determined by Allium assay, taking into account the reduction in CAs induced by NaN3. The Allium test is reliably used in both genotoxicity and antigenotoxicity tests71,72,73. Low level of CAs were detected in the control group, which were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Multipolar anaphase detected in other groups was not observed in the control group. Similar results were observed in the group treated with only M. chamomilla flower extract and low level of CAs were detected at a statistically insignificant level (p > 0.05). This result indicates that M. chamomilla flower extract has no genotoxic effect at the tested dose. The NaN3-treated group was considered as a positive control and statically significant high levels of abnormalities were detected in this group mompared to control (p < 0.05). NaN3 is a strong mutagen and it is reported in the literature that the azide metabolite interacts with DNA and causes chromosomal abnormalities19. In this study, the high frequency of CAs detected in the positive control group confirms NaN3 genotoxicity and the highest frequency of MN formation was observed in this group. MN formations may indicate direct DNA damage, i.e. clastogenic mechanism, or interaction with the DNA replication apparatus, i.e. aneugenic mechanism74,75. The sticky chromosome detected with a frequency of 75.9 ± 5.6 in the NaN3-treated group is due to changes in non-histone proteins (topoisomerase II and peripheral proteins). Other CAs may occur when chromatids in sticky regions are physically stretched and broken. Chromosomal breaks due to stickiness is therefore a secondary effect requiring anaphase movement, in contrast to breakage due to the direct effect of mutagens on DNA76. Among the CAs, the vagrant chromosome, which was detected with a frequency of 42.6 ± 6.5, is a chromosome oriented to the poles apart from its chromosomal group. This abnormality may be associated with the failure of the spindle threads to organize normally. This abnormality can result in uneven segregation of chromosome numbers in daughter cells, which can lead to polyploidy and aneuploidy77. Fragments are abnormalities caused by chromosome breaks. Vagrant chromosomes and fragments can also cause an increase in the frequency of MN in cells. Chromosome bridges, which were detected with a frequency of 10.9 ± 3.5 in the positive control group, are formed by the fusion of the sticky ends of broken chromosomes78. Multipolar anaphase induced by NaN3 is an abnormality in which chromosomal material is attracted to more than two poles. Multipolarity is a phenomenon usually associated with an increase in centrosome number. As a result of this abnormality, the cell may stop before completing cytokinesis and it is difficult to achieve a uniform distribution of chromosomes. For these reasons, multipolarity is recognized as an important source of genomic instability21,79.

While NaN3 caused various types and frequencies of CAs, NaN3 treatment with the extract decreased the frequency of these abnormalities. Among the abnormalities, the most significant reduction was observed in MN frequency. M. chamomilla flower extract reduced NaN3-induced MN formation to a statistically significant extent (58%, p < 0.05). Except for the sticky chromosome, all abnormalities were reduced by more than 50%. This result indicates that M. chamomilla flower extract exhibits a significant antigenotoxic effect and that this effect may be potentiated with dose increase. M. chamomilla flower extract, which reduced the chromosomal damages induced by NaN3, did not exhibit any genotoxic effect when applied alone. This result shows that M. chamomilla flower extract is an antigenotoxic agent that does not exhibit toxic effects. There are studies in the literature reporting the antigenotoxic effects of M. chamomilla extracts in different organisms. Hernandez-Ceruelos et al.80 reported that M. chamomilla extract and the essential oils it contains provide protection against induced DNA damage in mouse bone marrow and exhibit antigenotoxic effects. Tawfik et al.81 reported that M. chamomilla essential oils reduce the frequency of many anomalies such as gap, broken, dysentric chromosomes in mice.

The antigenotoxic effects of the main components caffeic acid, quercetin and kaempferol alone were investigated by Allium test and it was determined that each component alone regressed the CAs induced by the positive agent. Caffeic acid showed the most pronounced antigenotoxic effect against fragment formation and caused 39.5% regression of this abnormality type. M. chamomilla flower extract alone provided 56.2% protection against this abnormality. Quercetin reduced MN abnormalities by 40%, while the flower extract reduced these abnormalities by 58%. Kaempferol showed a lower antigenotoxic effect compared to the other main components and provided a reduction in abnormalities in the range of 18.5%-23.6%. The higher antigenotoxic effect of the M. chamomilla flower extract than the activity of main components (individually) indicates the contribution and synergistic effect of the other components. This synergism can be explained by several mechanisms. The most likely mechanism is that different compounds act on different targets. For example, while one substance neutralizes reactive oxygen species (ROS), another may activate DNA repair enzymes and work together against genotoxic damage. Synergistic antigenotoxic effects may also occur through complementary modulation of antioxidant defense systems and cooperative mechanisms of DNA damage/repair82. However, further studies using combination analyses are needed to confirm possible synergistic interactions between the components of the extract. Similarly, Vattem et al.83 reported that phenolics in plant extracts exhibited a synergistic effect, resulting in a stronger antimutagenic effect.

Anti-inflammatory activity

Determination of protein denaturation inhibition is a valuable method for detecting anti-inflammatory compounds without the use of live subjects. Protein denaturation is an important step in inflammation and is associated with the onset of inflammatory and arthritic complications due to auto-antigen production. Herbal extracts, which are safe and readily available sources, are being investigated as an alternative to anti-inflammatory drugs with undesirable side effects84. The BSA denaturation inhibition data of the extract, main components and the positive control aspirin are given in Fig. 5. A concentration-independent inhibition of BSA denaturation in the range 50–600 μg/mL was observed for all tested compounds. The extract and the three main components have lower inhibition rate with higher IC50 values compared to the positive control in the anti-inflammatory test. Aspirin showed 100% inhibition at 600 µg/mL, while its IC50 value was 235 µg/mL. M. chamomilla flower extract, showed an inhibition in the range of 23.5% to 71% and its IC50 value was 408 µg/mL. The IC50 values of caffeic acid, quercetin and kaempferol, which are the main components of flower extract, were calculated as 306 µg/mL, 283 µg/mL and 333 µg/mL, respectively. These results indicate that the flower extract exhibited a lower anti-inflammatory activity than the other tested agents. This may be explained by the fact that the positive control and the main components were pure, while the flower extract contained different components that may show antagonist effect85. The lower protein denaturation inhibition of the flower extract compared to the main components can be attributed to possible mechanisms such as the active compounds reacting with each other in the reaction medium and forming precipitates/complexes, one component stabilizing the protein while the other inhibits stabilization, some compounds changing the pH of the reaction medium and disrupting the stabilization of other compounds86. However, further studies using combination analyses are needed to confirm possible antagonistic interactions between the components of the extract.

In-silico receptor interactions

The in-silico interaction of the GABAA receptor with the four major components detected in M. chamomilla flower extract is given in Fig. 6 and Table 3. The interaction of caffeic acid with GABAA was predominantly via hydrogen bonding and tryptophan, serine, arginine, asparagine and aspartic acid were predominantly involved in this binding. The binding energy of this interaction is − 5.01 kcal/mol. In the interaction between gentisic acid and GABAA, an inhibition constant of 351.67 µM was determined; phenylalanine, lysine, arginine, serine and valine are the amino acids involved in hydrogen bonding. The binding energies obtained in the interaction of kaempferol and quercetin were calculated as − 5.47 kcal/mol and − 4.41 kcal/mol, respectively, and hydrogen bonding, pi-cation, pi-pi and pi-sigma bonds were involved in these interactions. The more negative the values, the stronger the binding free energy between receptor and ligand87. Kaempferol exhibited the best binding conformation to the GABAA receptor with a binding energy of − 5.47 kcal/mol, followed by caffeic acid with -5.01 kcal/mol. These values are considered weak to moderate binding. The low/moderate binding energy of the tested active ingredients suggests that the other components may produce stronger GABAA inhibition than tested ingredients in the M. chamomilla flower, which is known for its sedative effect. Furthermore, weaker binding generally provides transient and reversible interactions, which may be preferable in some treatment approaches to limit toxicity. Therefore, a binding profile that balances dose, selectivity, and clinical targets may be advantageous, as well as strong binding. Further studies examining the interactions of each compound individually will contribute to elucidating the mechanism. Inhibition constant value is the half-maximal inhibition of a molecule by a chemical compound and this value is used to predict the change in function and inhibition potential of proteins, receptors and enzymes. Compounds with less than 100 mM inhibition constant are considered potential inhibitors. An inhibition constant greater than 100 mM indicates a low potential for inhibition88,89. Kaempferol, which has an inhibition constant of 98.54 µM among the ligands, is a potential inhibitor for GABAA and can be said to have a significant contribution to the calming effect due to its presence in major proportions in M. chamomilla flower extract. In the literature, it is reported that hypnotic effects on sleep–wake cycles, tranquilizing and anxiolytic activities occur as a result of the binding of phenolics and flavonoids in M. chamomilla to receptors such as GABA, dopamine and noradrenaline90,91,92. Viola et al.93 reported that flavonoids found in Matricaria recutita flowers bind to GABA receptors in mice and anxiolytic activity occurs.

Conclusion

Herbs are utilised for the prevention and treatment of diseases, with minimal side effects. Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of herbal products in protecting cells against oxidative damage and chemical agents. A substantial body of research has been dedicated to the documentation of the antioxidant, antigenotoxic and anticarcinogenic properties of numerous plant species. The extensive plant biodiversity observed around the world, including in our own country, indicates that current research efforts are inadequate. Furthermore, geographical variation has been demonstrated to result in discrepancies in the phytochemistry and biological activity profile of the same plant species. Consequently, further research is required to investigate the biological and pharmacological effects of plant species and their active constituents. It is evident that studies pertaining to biological activity, particularly those associated with phytochemical content, are of considerable value. The present study demonstrated that M. chamomilla flower extract has significant biological activities, including antioxidant, antigenotoxic and potential neuroactive effects. Phytochemical analysis identified caffeic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol as the main components, along with numerous phenolic compounds, each contributing to distinct biological properties. The study investigated the biological activities of not only the extract but also the main components, assessing potential synergistic or antagonistic relationships by comparing them with the extract activity. The main components exhibited stronger antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, while the flower extract exhibited stronger antimicrobial and antigenotoxic activity. This suggests that synergistic and antagonistic relationships develop specifically for biological activity. While the study provides new insights, particularly regarding the genotoxic safety profile and synergistic/antagonistic interactions within the extract, significant gaps remain. Further studies using combination analyses are needed to confirm potential antagonistic and synergistic interactions among the extract components. Furthermore, the variability of phytochemical composition across geographic regions necessitates more comprehensive chemotypic and pharmacological profiling. Future research aims to isolate bioactive compounds, elucidate their mechanisms of action, and validate these effects through in vivo and clinical studies. Such efforts are crucial for fully exploiting the therapeutic potential of M. chamomilla and developing standardized and effective phytopharmaceuticals.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sorokina, M. & Steinbeck, C. Review on natural products databases: where to find data in 2020. J. Cheminf. 12(1), 20 (2020).

El Mihyaoui, A. et al. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): a review of ethnomedicinal use, phytochemistry and pharmacological uses. Life 12(4), 479 (2022).

Inceer, H. & Bal, M. Morphoanatomical study of Matricaria L. (Asteraceae) in Turkey. Bot. Serbica 43(2), 151–159 (2019).

Inceer, H. & Ozcan, M. Taxonomic evaluations on the anatomical characters of leaf and achene in Turkish Tripleurospermum with its relative Matricaria (Asteraceae). Flora 275, 151759 (2021).

Mavandi, P., Assareh, M. H., Dehshiri, A., Rezadoost, H. & Abdossi, V. Flower biomass, essential oil production and chemotype identification of some Iranian Matricaria chamomilla Var. recutita (L.) accessions and commercial varieties. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 22(5), 1228–1240 (2019).

El-Assri, E. M. et al. Wild chamomile (Matricaria recutita L) from the taounate province, morocco: Extraction and valorisation of the antibacterial activity of its essential oils. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 5(5), 883–888 (2021).

Abbas, A. M., Seddik, M. A., Gahory, A. A., Salaheldin, S. & Soliman, W. S. Differences in the aroma profile of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) after different drying conditions. Sustainability 13(9), 5083 (2021).

El-Hefny, M., Abo Elgat, W. A., Al-Huqail, A. A. & Ali, H. M. Essential and recovery oils from Matricaria chamomilla flowers as environmentally friendly fungicides against four fungi isolated from cultural heritage objects. Processes 7(11), 809 (2019).

Ghoniem, A. A. et al. Enhancing the potentiality of Trichoderma harzianum against Pythium pathogen of beans using chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla, L.) flower extract. Molecules 26(4), 1178 (2021).

Petruľová-Poracká, V., Repčák, M., Vilková, M. & Imrich, J. Coumarins of Matricaria chamomilla L.: aglycones and glycosides. Food Chem. 141(1), 54–59 (2013).

Lima, V. N. et al. Antimicrobial and enhancement of the antibiotic activity by phenolic compounds: gallic acid, caffeic acid and pyrogallol. Microbial Pathogen. 99, 56–61 (2016).

Al-Ismail, K. M. & Talal Aburjai, T. A. A study of the effect of water and alcohol extracts of some plants as antioxidants and antimicrobial on long-term storage of anhydrous butter fat. Sci. Food Agric. 84(2), 173–178 (2004).

Rahman, H. & Chandra, A. Microbiologic evaluation of matricaria and chlorhexidine against E. faecalis and C. albicans. Indian J. Den. 6(2), 60 (2015).

Hajaji, S. et al. Anthelmintic activity of Tunisian chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) against Haemonchus contortus. J. Helminthol. 92(2), 168–177 (2018).

Villa-Rodriguez, J., Kerimi, A., Abranko, L. & Williamson, G. German Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) extract and its major polyphenols inhibit intestinal α-glycosidases in vitro. FASEB J. 29, LB323 (2015).

Kupfersztain, C., Rotem, C., Fagot, R. & Kaplan, B. The immediate effect of natural plant extract, Angelica sinensis and Matricaria chamomilla (Climex) for the treatment of hot flushes during menopause. A preliminary report. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 30(4), 203–206 (2003).

Zick, S. M., Wright, B. D., Sen, A. & Arnedt, J. T. Preliminary examination of the efficacy and safety of a standardized chamomile extract for chronic primary insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. BMC Complement. Alter. Med. 11, 1–8 (2011).

Aydin, D., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Metal chelating and anti-radical activity of Salvia officinalis in the ameliorative effects against uranium toxicity. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 15845 (2022).

Ayhan, B. S., Yalçın, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Antidiabetic potential and multi-biological activities of Trachystemon orientalis extracts. J. Food Meas. Charact. 13(4), 2887–2893 (2019).

Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Spectroscopic contribution to glyphosate toxicity profile and the remedial effects of Momordica charantia. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 20020 (2022).

Güç, İ, Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Toxicity mechanisms of aflatoxin M1 assisted with molecular docking and the toxicity-limiting role of trans-resveratrol. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 14471 (2022).

Bakir Çilesizoğlu, N., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Sipahi Kuloğlu, S. Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening of Nerium oleander L. extracts associated with toxicity profile. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 21421 (2022).

Durhan, B., Yalçın, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Molecular docking assisted biological functions and phytochemical screening of Amaranthus lividus L. extract. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 4308 (2022).

Üst, Ö., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Özkan, B. LC–MS/MS, GC–MS and molecular docking analysis for phytochemical fingerprint and bioactivity of Beta vulgaris L. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 7491 (2024).

Akman, C. T. et al. LC-ESI-MS/MS Chemical characterization, antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of propolis extracted with organic solvents from eastern anatolia region. Chem. Biodiversity 20(5), e202201189 (2023).

Macar, T. K., Macar, O., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Resveratrol ameliorates the physiological, biochemical, cytogenetic, and anatomical toxicities induced by copper (II) chloride exposure in Allium cepa L. ESPR. 27(1), 657–667 (2020).

Altunkaynak, F., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçin, E. Detection of heavy metal contamination in Batlama Stream (Turkiye) and the potential toxicity profile. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 11727 (2023).

Doğan, M., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçin, E. & Acar, A. Comprehensive toxicity screening of Pazarsuyu stream water containing heavy metals and protective role of lycopene. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 16615 (2022).

Acar, A., Çavuşoğlu, K., Türkmen, Z., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. The investigation of genotoxic, physiological and anatomical effects of paraquat herbicide on Allium cepa L. Cytologia 80(3), 343–351 (2015).

Himtaş, D., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. In-vivo and in-silico studies to identify toxicity mechanisms of permethrin with the toxicity-reducing role of ginger. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(6), 9272–9287 (2024).

Çavuşoğlu, D., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Mitigative effect of green tea extract against mercury (II) chloride toxicity in Allium cepa L. model. ESPR. 29(19), 27862–27874 (2022).

Kedi, P. B. E. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis, characterization, in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of silver nanoparticle-mediated Selaginella myosurus aqueous extract. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 8537–8548 (2018).

Macar, O., Macar, T. K., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Molecular docking and spectral shift supported toxicity profile of metaldehyde mollucide and the toxicity-reducing effects of bitter melon extract. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 187, 105201 (2022).

Çakir, F., Kutluer, F., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Deep neural network and molecular docking supported toxicity profile of prometryn. Chemosphere 340, 139962 (2023).

Onur, M., Yalçın, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Elucidating the toxicity mechanism of AFM2 and the protective role of quercetin in albino mice. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1237 (2023).

National Library of Medicine https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (2024).

Protein Data Bank https://www.rcsb.org/ (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Resolving native GABAA receptor structures from the human brain. Nature 638(8050), 562–568 (2025).

Release Notes https://www.schrodinger.com/life-science/download/release-notes/release-2023-1/ (2024).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30(16), 2785–2791 (2009).

BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download (2024).

Akgeyik, A. U., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Phytochemical fingerprint and biological activity of raw and heat-treated Ornithogalum umbellatum. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 13733 (2023).

Roby, M. H. H., Sarhan, M. A., Selim, K. A. H. & Khalel, K. I. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 44, 437–445 (2013).

Espíndola, K. M. M. et al. Chemical and pharmacological aspects of caffeic acid and its activity in hepatocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 9, 541 (2019).

Silva, T., Oliveira, C. & Borges, F. Caffeic acid derivatives, analogs and applications: a patent review (2009–2013). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 24(11), 1257–1270 (2014).

Sidoryk, K., Jaromin, A., Filipczak, N., Cmoch, P. & Cybulski, M. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of caffeic acid derivatives. Molecules 23(9), 2199 (2018).

Ozgen, S., Kilinc, O. K. & Selamoğlu, Z. Antioxidant activity of quercetin: a mechanistic review. TURJAF 4(12), 1134–1138 (2016).

Kalantari, H. et al. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of Capparis spinosa L. fractions and quercetin on tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced acute liver damage in mice. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 8(1), 120–127 (2018).

Osonga, F. J. et al. Antimicrobial activity of a new class of phosphorylated and modified flavonoids. ACS Omega 4(7), 12865–12871 (2019).

Periferakis, A. et al. Kaempferol: a review of current evidence of its antiviral potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(22), 16299 (2023).

M Calderon-Montano, J., Burgos-Morón, E., Pérez-Guerrero, C. & López-Lázaro, M. A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol. Mini-Ree. Med. Chem. 11(4), 298–344 (2011).

Haghi, G., Hatami, A., Safaei, A. & Mehran, M. Analysis of phenolic compounds in Matricaria chamomilla and its extracts by UPLC-UV. Res. Pharm. Sci. 9(1), 31–37.

De Angelis, M. et al. Rapid determination of phenolic composition in chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem. 463, 141084 (2025).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçın, E. & Yapar, K. Lycopene: an antioxidant product reducing dithane toxicity in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2290 (2023).

Kutluer, F., Güç, İ, Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Toxicity of environmentally relevant concentration of esfenvalerate and Taraxacum officinale application to overcome toxicity: A multi-bioindicator ın-vivo study. Environ. Pollut. 373, 126111 (2025).

Topatan, Z. Ş et al. Alleviatory efficacy of Achillea millefolium L. in etoxazole-mediated toxicity in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 14, 31674 (2024).

Kesti, S., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Investigation of the protective role of Ginkgo biloba L. against phytotoxicity, genotoxicity and oxidative damage induced by trifloxystrobin. Sci. Rep. 14, 19937 (2024).

Al-Dabbagh, B. et al. Antioxidant and anticancer activities of chamomile (Matricaria recutita L). BMC Res. Notes 12, 1–8 (2019).

Stanojevic, L. P., Marjanovic-Balaban, Z. R., Kalaba, V. D., Stanojevic, J. S. & Cvetkovic, D. J. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of chamomile flowers essential oil (Matricaria chamomilla L.). J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 19(8), 2017–2028 (2016).

Kesti Usta, S., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Synergistic and antagonistic contributions of main components to the bioactivity profile of Anethum graveolens extract. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 21465 (2025).

Joshi, T., Deepa, P. R. & Sharma, P. K. Effect of different proportions of phenolics on antioxidant potential: pointers for bioactive synergy/antagonism in foods and nutraceuticals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 92(4), 939–946 (2022).

Breijyeh, Z., Jubeh, B. & Karaman, R. Resistance of gram-negative bacteria to current antibacterial agents and approaches to resolve it. Molecules 25(6), 1340 (2020).

Walker, L. A., Gow, N. A. & Munro, C. A. Elevated chitin content reduces the susceptibility of Candida species to caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 146–154 (2013).

Kameri, A. et al. Antibacterial effect of Matricaria chamomilla L. extract against Enterococcus faecalis. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 13–20 (2023).

Boudieb, K., Kaki, S. A. S. A., Oulebsir-Mohandkaci, H. & Bennacer, A. Phytochemical characterization and antimicrobial potentialities of two medicinal plants, Chamaemelum nobile (L.) All and Matricaria chamomilla (L.). Int. J. Innov. Approaches Sci. Res. 2, 126–139 (2018).

Osman, M. Y., Taie, H. A., Helmy, W. A. & Amer, H. Screening for antioxidant, antifungal, and antitumor activities of aqueous extracts of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla). Egypt. Pharm. J. 15(2), 55–61 (2016).

Lou, Z. et al. p-Coumaric acid kills bacteria through dual damage mechanisms. Food Control 25(2), 550–554 (2012).

Fitzgerald, D. J. et al. Mode of antimicrobial action of vanillin against Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus plantarum and Listeria innocua. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97(1), 104–113 (2004).

Abu-Hussien, S. H. et al. Synergistic antimicrobial activity of essential oils mixture of Moringa oleifera, Cinnamomum verum and Nigella sativa against Staphylococcus aureus using L-optimal mixture design. AMB Express 15(1), 15 (2025).

De Oliveira, E. F. et al. Screening of antimicrobial synergism between phenolic acids derivatives and UV-A light radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 214, 112081 (2021).

Kaya, M., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçin, E. & Acar, A. DNA fragmentation and multifaceted toxicity induced by high-dose vanadium exposure determined by the bioindicator Allium test. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 8493 (2023).

Tümer, C., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçin, E. Screening the toxicity profile and genotoxicity mechanism of excess manganese confirmed by spectral shift. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 20986 (2022).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Acute multiple toxic effects of Trifloxystrobin fungicide on Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 15216 (2022).

Gündüz, A., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Combined toxic effects of aflatoxin B2 and the protective role of resveratrol in Swiss albino mice. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 18081 (2021).

Demirtas, G., Çavusoglu, K. & Yalçin, E. Anatomic, physiologic and cytogenetic changes in Allium cepa L. induced by diniconazole. Cytologia 80(1), 51–57 (2015).

Gaulden, M. E. Hypothesis: some mutagens directly alter specific chromosomal proteins (DNA topoisomerase II and peripheral proteins) to produce chromosome stickiness, which causes chromosome aberrations. Mutagenesis 2(5), 357–365 (1987).

Demirtaş, G., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçin, E. Aneugenic, clastogenic, and multi-toxic effects of diethyl phthalate exposure. ESPR. 27(5), 5503–5510 (2020).

Kutluer, F., Özkan, B., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Direct and indirect toxicity mechanisms of the natural insecticide azadirachtin based on in-silico interactions with tubulin, topoisomerase and DNA. Chemosphere 364, 143006 (2024).

Nefic, H., Musanovic, J., Metovic, A. & Kurteshi, K. Chromosomal and nuclear alterations in root tip cells of Allium cepa L. induced by alprazolam. Med. Arch. 67(6), 388 (2013).

Hernandez-Ceruelos, A., Madrigal-Bujaidar, E. & De La Cruz, C. Inhibitory effect of chamomile essential oil on the sister chromatid exchanges induced by daunorubicin and methyl methanesulfonate in mouse bone marrow. Toxicol. Lett. 135(1–2), 103–110 (2022).

Tawfik, S. S., Ahmed, M. M., Said, Z. S. & Mohamed, M. R. Cytogenetic and biochemical competency of chamomile essential oil against γ-rays induced mutagenic effects in mice. Int. J. Rad. Res. 16(1), 55–64 (2018).

Słoczyńska, K., Powroźnik, B., Pękala, E. & Waszkielewicz, A. M. Antimutagenic compounds and their possible mechanisms of action. J. Appl. Genet. 55(2), 273–285 (2014).

Vattem, D. A., Jang, H. D., Levin, R. & Shetty, K. Synergism of cranberry phenolics with ellagic acid and rosmarinic acid for antimutagenic and DNA protection functions. J. Food Biochem. 30(1), 98–116 (2006).

Elkolli, H. et al. In vitro and in-silico activities of E. radiata and E. cinerea as an enhancer of antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory agents. Molecules 28(20), 7153 (2023).

Sangeetha, G. & Vidhya, R. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of different parts of Pedalium murex (L.). Inflammation 4(3), 31–36 (2016).

Cascorbi, I. Drug interactions—principles, examples and clinical consequences. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 109(33–34), 546 (2012).

Terefe, E. M. & Ghosh, A. Molecular docking, validation, dynamics simulations, and pharmacokinetic prediction of phytochemicals isolated from Croton dichogamus against the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Bioinform. Biol. Insigh. 16, 11779322221125604 (2022).

Zhao, B. Q. et al. Antitubercular and cytotoxic tigliane-type diterpenoids from Croton tiglium. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 4996–4999 (2016).

Zheng, X. & Polli, J. Identification of inhibitor concentrations to efficiently screen and measure inhibition Ki values against solute carrier transporters. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 41, 43–52 (2010).

Marder, M. & Paladini, A. C. GABA-A-receptor ligands of flavonoid structure. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2(8), 853–867 (2002).

Awad, R. et al. Effects of traditionally used anxiolytic botanicals on enzymes of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system. Can. J. Physiol. Pharm. 85(9), 933–942 (2007).

Srivastava, J. K., Shankar, E. & Gupta, S. Chamomile: A herbal medicine of the past with a bright future. Mol. Med. Rep. 3(6), 895–901 (2010).

Viola, H. et al. Apigenin, a component of Matricaria recutita flowers, is a central benzodiazepine receptors-ligand with anxiolytic effects. Planta Med. 61, 213–216 (1995).

Acknowledgements

This study has not been financially supported by any institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. S. A: investigation; methodology; visualization; writing-review and editing. E.Y: conceptualization; methodology; data curation; software; visualization; writing-review and editing. K.Ç: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing-review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayhan, B.S., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. In-silico receptor interactions, phytochemical fingerprint and biological activities of Matricaria chamomilla flower extract and the main components. Sci Rep 15, 28875 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14729-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14729-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Chemical profiling by LC–MS/MS and GC–MS and biological activity assessment of different extracts of Portulaca oleracea through in-vitro and in-silico approaches

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Eco-friendly remediation of Triflumuron-induced stress with Capsella bursa-pastoris extract

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Transforming chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) infusion into a fermented beverage using sucrose and probiotic lactic acid bacteria

Discover Food (2025)

Hyrogen bond,

Hyrogen bond,  Unfavorable positive-positive,

Unfavorable positive-positive,  Pi-Aklyl,

Pi-Aklyl,  Pi-Cation,

Pi-Cation,  Pi-Sigma,

Pi-Sigma,  Pi-Pi Stacked.

Pi-Pi Stacked.