Abstract

We demonstrate a chip-integrated emission spectrometer capable of retrieving the temperature of the light sources. It consists of a single photon detector with low dark counts and a sweeping on-chip filter with 2 pm spectral resolution in the visible and near-infrared regimes. With wildfire sensing applications in mind, we test our system with a hollow cathode lamp to simulate the K-line emission, and show how the models of Doppler and collision broadening in the plasma can be used for temperature retrieval. With favorable device parameters, high spectral resolution, and a novel temperature retrieval capability, our technique may find broad applications in environmental monitoring, astrophysics, plasma physics, and so on.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Precise and reliable measurements of emission lines from light sources such as wildfire, celestial bodies, and fusion reactors serve important tools for environmental monitoring, astrophysics, plasma physics, and so on1,2,3,4,5. For example, trace element emissions from biomass burning have been studied for wildfire detection, for which, potassium lines around at 769.9 nm and 766.5 nm (associated respectively with the D\(_1\) and D\(_2\) transitions6,7), are strong due to its low ionization energy (4.34 eV). Aided by high atmospheric transmissivity8, long-distance wildfire sensing can be developed, on both airborne and spaceborne platforms1. However, the spectral resolution of existing devices is low (over 1 nm), which limits the measurement signal to noise and hinders the deployment in daytime due to the high solar background1,9,10.

Another important application area is with plasma physics, particularly in fusion reactor diagnostics, where the helium number density is a critical parameter for assessing the energy required to heat the plasma under specific confinement conditions and for predicting the fusion rate11,12. Excessive helium density could impede the fusion burn, creating a significant diagnostic challenge. Therefore, real-time measurement of helium density in the plasma core is essential. To this end, the emission spectra of plasma can provide ion density through profile intensity and temperature through linewidth. Yet the existing resolution is limited to 0.2 nm, which gives low intensity accuracy13.

Besides the demand for spectral resolution, wide deployment of remote spectroscopy measurement also calls for the systems’ favorable Size, Weight, and Power (SWaP) parameters. This is particularly emphasized by space-based missions, as putting a heavy and bulky spectrometer in a satellite incurs exceedingly high costs2.

Both of the above resolution and SWaP challenges can be addressed by new spectroscopy techniques based on photonic integrated circuits14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Among these, the thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) platform stands out due to its exceptionally low propagation loss, wide optical transparency window (near-UV to mid-IR), and efficient optical tuning using electro-/thermal-optical modulations21,22,23,24. Of particular relevance to spectroscopy are ultra-high-Q micro-ring resonators (MRR) in TFLN, for which an intrinsic Q-factor of \(2.9\times 10^7\) has been demonstrated25. Recently, we used thermally tunable MRR on lithium niobate on insulator (LNOI) for CO\(_2\)26 and O\(_2\)27 absorption spectroscopy to measure their atmosphere concentration, with millimeter sizes and picometer resolution.

Here, we explore LNOI circuits for emission spectroscopy, and demonstrate a novel capability in retrieving the temperature of the light sources. Our system consists of a single photon detector with low dark counts and a sweeping LNOI MRR filter with 2 pm spectral resolution in the visible and near-infrared regimes. With the wildfire sensing application in mind, we test our system with a hollow cathode lamp (HCL) to emulate the K-line emission, and show how the models of Doppler and collision broadening in the plasma can be used for temperature retrieval. With favorable SWaP parameters, high resolution, and temperature retrieval capabilities, our technique can find broad applications in environmental monitoring, astrophysics, plasma physics, and so on28,29.

Results

Device design and calibration

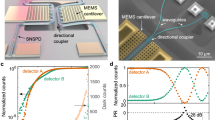

Figure 1a shows the circuit layout of the MRR filter used in this demonstration. It consists of a high-Q ring resonator and two pulley bus waveguides on the two sides of the ring, respectively26,27. On one side are the input and output ports, and on the other sides are the add and drop ports. The incoming signal is injected into the input port, and the filtered signal is collected at the drop port. To sweep the filter center wavelength, a zigzag heater surrounding the ring is deposited on top of the MRR, enabling thermal tuning of its resonant wavelengths. The efficiency of this control-termed tunability-is defined as the resonance wavelength shift per unit of heating power (\(\Delta \lambda _{res}/\Delta P_h\)) and is typically expressed in pm/mW. Here, the zigzag layout is to increase the heating area of the electrode and thus the heating efficiency. Alternatively, instead of the thermo-optic tuning, electro-optic tuning can be applied to utilize LN’s large electro-optic coefficients23. In comparison, the former is more power efficient, but the latter can achieve ultrahigh tuning speed (at hundreds of GHz, versus hundreds of KHz).

Unlike typical interference filters, the MRR filter has periodic transmission spectral windows, separated by free-spectral range (FSR) given by30

where \(\lambda\) is the center wavelength, R is the ring radius, and \(n_g\) is the group refractive index at the center wavelength. In typical settings, FSR is on the order of nanometers, so that the filter will admit not only the target signal photons, but also those in other periodic windows. Hence, if there is broad background noise, a coarse filter is needed to apply around the target wavelength for noise suppression.

For the current experiment, we design and fabricate the circuits on a 300-nm TFLN wafer, shallow etched to a height of 180 nm. The ring radius is \(R=40\) \(\mu\)m. The pulley and ring waveguides have top widths of 280 nm and 480 nm, respectively, with a sidewall angle of 82 degree. The detailed fabrication process and the circuit dimensions of the MRR can be found in the Methods section. These waveguide dimensions ensure that only the fundamental TE mode propagates in the waveguides and all the other modes are suppressed. For the center wavelength \(\lambda =770\) nm, the simulated group refractive index \(n_g=2.4038\), so that the FSR is 0.98 nm by design.

The microscope image of the fabricated chip is shown in Fig. 1a. To characterize its transmission spectrum, we use a tunable laser (New Focus TLB-6700) whose output wavelength can be swept using both coarse and fine scans, the latter of which significantly enhances the calibration accuracy over our previous measurement to reduce the measurement error from 2 pm to 0.03 pm27. The details of the calibration method can be found in the Methods section.

Because of the 0.98-nm FSR and the limited maximum fine scan range of 150 pm, we first use the laser internal coarse scan to locate the resonance wavelength. Then we perform a fine scan around the resonance wavelength with a scanning range of 51 pm. The measurement results are shown in Fig. 1b, where two TE00 modes are shown with a 0.98 nm FSR, as simulated. The resonance profile has a FWHM of 2-pm as shown in the inset of Fig. 1b, corresponding to a loaded cavity of \(Q=0.38\times 10^{6}\). Also shown in the figure are two wide transmission peaks, which correspond to TM00 modes, which have much higher propagation losses due to the waveguide dimension. The wavemeter measurement details of MRR characterization can be found in the Methods section.

(a) Microscope images of the MRR chip. (b) Calibration results, where we show a coarse scan of laser output for resonance characterization, alongside a fine scan using external frequency modulation for linewidth characterization. The fine scan range (51 pm) is indicated as the grey shaded region, with the inset showing a 2-pm FWHM measurement. The dashed lines represent the starting point of the scan wavelength. The left y-axes of the figures represent the photodiode (PD) output voltage, which is linear proportional to the output optical power from the MRR drop port. The right y-axes of the main figure and the inset indicate the DC motor voltage and the piezoelectric transducer (PZT) voltage of the laser, respectively, for the calibration.

In this experiment, we measure specifically the potassium emission lines for potential wildfire detection. To this end, we use a potassium hollow cathode lamp (HCL), which emits the K-line doublet at 766.5 nm and 769.9 nm, respectively. The spacing between the two is 3.4 nm, so that only one line can be transmitted by the MRR at a time when its resonance is thermo-optically tuned. To simultaneously detect both transmission lines, one may cascade two MRR’s in serial, with each’s resonance tuned to be at one line and the input port of a second MRR connected to the through port of the first. Because of the on-chip integration, there is no insertion loss between the two. By cascading more MRR’s, signals in many emission lines can be measured simultaneously.

In our chip design, the heating electrode will introduce additional loss to the cavity, due to the evanescent light absorption by the metal21,31. Thus it is desirable to spatially separate the electrode and the waveguide, so that there is little evanescent light reaching the electrode. However, if the gap between the two is large, the heater efficiency will be weak, so that the wavelength tunability is reduced. To achieve both low loss (thus high spectral resolution) and high tunability, we use a zigzag-shaped heater to encircle the ring, to increase the heating area and thus its efficiency. Positioning the zigzag on both sides of the ring waveguide increases the heating area while reducing the temperature gradient to provide uniform heating.

Figure 2 shows the measured trade-off between the cavity linewidth and thermo-optic tunability when the lateral distance is varied between the electrode and waveguide. From the figure, when the distance exceeds 2.8 \(\mu\)m, the linewidth is nearly not affected by metal absorption. Yet the tunability remains sufficiently large for this experiment. In our current design, the distance is 2.8 \(\mu\)m as we are interested in measuring accurately the emission linewidth. To characterize the tunability, we apply voltage manually from 17 to 26 V, at a step size of 0.5 V. For each voltage, the heater power is calculated using \(P_{h}(V)=V^2/R_{h}\), where \(R_{h}\) is the heater’s resistance. The shifted resonance wavelength \(\lambda _{res} (V)\) is measured using the tunable the laser. Figure 3 shows tunability of MRR with distance 2.8 \(\mu m\) used for our experiment. The slope of the linear fitting line \(\Delta \lambda _{res}/\Delta P_{h}\) indicates a tunability of 6.3691 pm/mW. The coefficient of fitting determination, \(r^2 = 1\), confirms the excellent linearity of the response. For other applications, one may choose an appropriate distance according to the trade-off, based on the specific application needs.

Experiment

The experiment for detecting potassium D lines is illustrated in Fig. 4. A hollow cathode lamp (HCL, Scinteck SI-HC-200042) is used as the light source for the K doublet emission. We apply a current of 8 mA and a voltage of 280 V to generate an intense electric field between the lamp’s cathode and anode, where the inert Ne gas is ionized. The electrons emitted from the cathode, along with Ne ions, form a conducting plasma that excites potassium atoms to higher energy states. As the potassium atoms decay, they emit narrow D lines through a quartz window. A thin lens \(L_1\) with a focal length of 100 mm collimates the diverging thermal light, which is then focused by a second lens \(L_2\) with a 75 mm focal length. Short-pass (SP) and long-pass (LP) filters are employed to limit the spectral range to 750–800 nm, while effectively avoiding interference from other emission lines. The light is coupled into a multimode fiber (MMF) via a fiber coupler, where a single-mode fiber (SMF) is spliced with the MMF. The light passes through a fiber polarization controller (FPC) before coupled into the MRR chip via a lensed fiber. The MRR is mounted on a stage equipped with a thermoelectric cooler (TEC, Vescent Photonics, Slice-QTC) that actively stabilizes the temperature at \(300\pm 0.003\) K, which is the same as the stage temperature used during calibration. This ensures a stable thermal environment, effectively mitigating ambient fluctuations that could otherwise induce resonance shifts. A power supply (GWINSTEK GPD-2303S) is used to sweep the resonance wavelength of the MRR by 200 pm by adjusting the applied voltage. When the resonance wavelength aligns with the potassium D-line, the emitted photons will pass through the MRR and reach a single-photon detector (PerkinElmer SPCM-AQR-14-FC-11260) through the drop port. The detector output pulses are registered by a counter (Thorlabs SPCNT) over a 1-second integration time to suppress Poissonian noise. During the process, a computer tunes the MRR resonance wavelength by controlling the power supply and records the photon counts at the same time.

Experiment setup. HCL: hollow cathode lamp. L\(_1\): thin lens with 100 mm focal length. LP: long-pass filter. SP: short-pass filter. L\(_2\): thin lens with 75 mm focal length. MMF: multi-mode fiber (orange line). SMF: single-mode fiber (blue line). FPC: fiber polarization controller. TEC: thermoelectric cooler. SPCM: single photon counting module. SPCNT: single photon counting device. The green lines denote the 780 nm lens fiber. The black lines represent electric wires.

The photon counting results are shown in Fig. 5, where (a) and (b) are for the potassium D2 and D1 lines, respectively. For the D2 line, the power supply voltage is increased from 17 to 26 V, at a step size of 0.1 V scanned automatically by the computer. The computer also automatically converts the applied voltage to the corresponding resonance wavelength by the relationship

where the second term calculates the resonance wavelength shift induced by the heater power difference between the applied voltage V and the initial voltage \(V_0\). As a result, the D-line profiles directly show photon counts as a function of wavelength. Hence, the accuracy of the calibrated tunability \(\Delta \lambda _{res}/\Delta P_{h}\) and initial wavelength \(\lambda _{res}(V_0)\), determines the precision of the measured wavelengths of the D-lines. The filtered wavelengths match well with the NIST database values of 766.5 nm and 769.9 nm6. The dark count is measured as \(147\pm 11\) Hz.

Temperature retrieval by linewidth

Thus far, the reported method for temperature retrieval of wildfire relies on broadband spectral radiance fitted by the Planck function10. It is susceptible to errors due to the background spectrum of reflected solar radiance background which is also broadband. On the other hand, temperature in plasma is typically determined by the Boltzmann plot of multiple emission lines, which is prone to significant retrieval errors due to intensity fluctuations29. Similarly, temperature retrieval of stars using luminosity in the Stefan-Boltzmann equation requires stellar radius or angular diameter data32, with radius or distance uncertainty affecting accuracy. Spectral contamination further impacts luminosity accuracy.

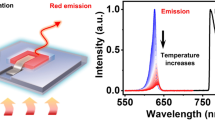

Here, we introduce a novel method of temperature retrieval using the fine measurement of emission linewidth with the MRR filter. In this experiment, by varying the lamp current from 8 mA to 40 mA, the cathode temperature is raised, which, in turn, boosts the emitted current from the cathode. This leads to a higher plasma charge density and, consequently, an elevated plasma temperature33. The increase in temperature enhances the thermal motion of potassium atoms, resulting in greater Doppler broadening of the linewidth. Therefore, linewidth broadening is observed with increasing lamp current.

Measured linewidth vs lamp current. The lamp current is scanned from 8 to 40 mA. For each applied lamp current, the linewidth measurement was repeated three times. The scattered points represent the mean linewidth values, with error bars indicating the standard deviation across the repeated measurements.

Figure 6 plots the change of linewidth as the lamp current is varied. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three repeated linewidth measurements taken at each lamp current. The emitted light spectrum from the lamp is a convolution of Doppler broadening, caused by thermal motion, and collision broadening, which arises from the reduced lifetime of the excited state of potassium atoms due to collisions11. This results in a Voigt profile \(V_{e}(\lambda ,T)=G(\lambda ,T)\otimes L_1(\lambda ,T)\), where \(G(\lambda , T)\) is the Gaussian profile describing the Doppler broadening and \(L_1 (\lambda , T)\) is the lamp collision broadening Lorentzian profile. The observed linewidth is the result of a further convolution between the Voigt profile \(V_e(\lambda ,T)\) and the Lorentzian profile of the ring resonator \(L_2(\lambda )\). Associative property of convolution allows us to first convolve the lamp collision Lorentzian with the ring Lorentzian, yielding a combined Lorentzian profile \(L(\lambda ,T) = L_1(\lambda ,T)\otimes L_2(\lambda )\). The total observed spectrum is therefore a Voigt profile

In the retrieval model, we first compute the linewidth of the combined Lorentzian profile \(L(\lambda ,T)\) to simplify the calculation, as the resulting combined Lorentzian profile has a linewidth just equal to the sum of the individual Lorentzian linewidths:

where \(\Delta \lambda _{1,2}\) are the FWHM of \(L_{1,2}\), respectively. The collision broadening linewidth, as given by34, can be extended to address the specific conditions in this work. An illustration of the collision processes is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a. Here, the Ne gas is partially ionized to form Ne ions. These Ne ions and electrons, present in equal densities, form a conducting plasma between the cathode and anode of the HCL. Therefore, we have \(n=n_{Ne}+n_{Ne^+}\), where n represents the total number density of particles, that consist of unionized neutral Ne with density \(n_{Ne}\) and ionized Neon with density \(n_{Ne^+}\). The density of Neon ions in plasma is equal to the density of electrons, expressed as \(n_{Ne^+}=n_e\). The collision broadening linewidth is then modified to account for these plasma conditions as

Here \(\Delta \lambda _0\) is the potassium natural linewidth, which is 0.012 pm35. The subscript K denotes the potassium atoms, and s represents the species that the potassium atoms collide with in the medium of the HCL glass tube, such as electrons (e), Ne ions (Ne\(^+\)), or neutral Ne atoms (Ne). The mole fraction of the species s is denoted by \(\chi _s\). The scattering cross section is given by \(\sigma _{s-K}=\pi (a_s+a_K)^2\) where \(a_s\) and \(a_K\) are the radii of the mole fraction of the species s and potassium atoms, respectively. \(\bar{v}_{s-K}\) is the mean relative speed, with \(\bar{v}_{s-K}=\sqrt{\bar{v}_s^2+\bar{v}_K^2}\), where \(\bar{v}_s=\sqrt{8k_BT/\pi M_s}\), and \(\bar{v}_K=\sqrt{8k_BT/\pi M_K}\). \(M_s\) and \(M_K\) are masses of species s and potassium atoms, respectively. \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant. In this context, the relations \(\chi _{Ne}+\chi _e=1\) and \(\chi _e=\chi _{Ne+}\) hold. Given that the lamp plasma is considered to be weakly ionized and assuming local thermal equilibrium (LTE) for particles in the glass tube, the fraction of Ne ions \(\chi _{Ne+}\), or the electron fraction \(\chi _e\), also referred to as the degree of ionization, can be related to the temperature via the Saha equation36.

in which the thermal de Broglie wavelength is \(\lambda _{\text {th}}=h/\sqrt{2\pi M_e k_B T}\). The degeneracy ratio of Neon ion to neutral Neon is given by \(g_1/g_0=4\)37. The first ionization energy of Ne is \(\epsilon =21.56454\) eV38. In the retrieval calculation we use neutral Ne and Ne ion radii \(a_{Ne}=0.02\) nm and \(a_{Ne+}=0.112\) nm, Ne mass \(M_{Ne}=M_{Ne+}=20.1797\) amu, potassium atomic radius \(a_{K}=0.235\) nm, potassium mass \(M_{K}=39.0983\) amu, electron radius \(a_{e}=2.8179\times 10^{-6}\) nm, and electron mass \(M_{e}=9.11\times 10^{-31}\) kg. Because the sealed glass tube has a constant volume and inert gas Ne particle numbers, we can determine the total number density, which is independent of temperature, by applying the ideal gas law, \(n=p/kT\). By using \(p=5\) torr at \(T=300\) K, the calculated total number density is \(n=1.61\times 10^{23}\) m\(^{-3}\), which is on same order as reported in Ref.29.

The Doppler broadening linewidth is defined as34

Then, by using the approximation relation between the FWHM of Voigt, Gaussian, and Lorentzian profiles, the FWHM of Voigt spectrum for the observed light in Eq. (3) is then given to a very good approximation as39:

The retrieved temperature using plasma model is shown in Fig. 7.

Retrieved temperature vs the lamp current with the plasma model incorporated, where the error bar is calculated through error propagation using the data in Fig. 6.

As a comparison, the retrieved temperature is on the same order of magnitude (\(\times 10^4\) K) of the temperature retrieved by Boltzmann plot in Ref. 29, where a similar hollow cathode discharge was employed for a laboratory-scale astrophysics experiment. To verify the validity of the retrieval model and gain insight into broadening mechanisms, we analyze the plasma ionization and the broadening competition in Supplementary Section S1. Note that this retrieved temperature is almost one order of magnitude less than the model without considering plasma (completely unionized); see more discussions in Supplementary Section S2.

The validity of the LTE assumption in this model can be evaluated using Griem’s criterion, which defines the critical electron density required for collisional rates to dominate over radiative decay: \(n_e\gtrsim 9.2\times 10^{23}\bigl (E_{12}/{E_1^H}\bigr )^3\sqrt{kT/{E_1^H}}\) m\(^{-3}\), where \(E_{12}\) is the excitation energy from state 1 to state 2, and \(E_H\) is the ionization energy (13.6 eV) of the hydrogen atom in the ground state40,41,42. Taking \(E_{12}=1.61\) eV of potassium atom and \(T\approx 10^4\) K, the criterion gives \(n_e\gtrsim 1.12\times 10^{21}\) m\(^{-3}\). Given the total particle density \(n=1.61\times 10^{23}\) m\(^{-3}\), a degree of ionization \(\chi _e\gtrsim 0.7\%\) would be sufficient to satisfy the LTE condition. Reported electron densities in HCL plasmas (\(\sim 10^{23}\) m\(^{-3}\))29 and our Supplementary Fig. S1 (showing \(\chi _e\) from \(0.0065\%\) to \(18\%\)) support this. Starting from \(I=10\) mA, where \(\chi _e=1.6\%>0.7\%\), the electron densities are beyond the threshold of the Griem’s criterion. At lower currents, plasma density may fall short of LTE conditions. In such non-LTE regimes, applying the Saha equation may lead to temperature errors. A more accurate alternative is to use a collisional–radiative model (CRM), which accounts for both collisional and radiative processes43.

Application

The demonstrated single-photon counting MRR spectroscopy have broad applications, ranging from detecting wildfires, to measuring fusion plasma and celestial bodies such as stars and black hole accretion disks in active galactic nuclei (AGN). For those applications, distinct circuit designs and retrieval models may be required to achieve the optimal performance. Table 1 lists the emission bands, temperature range, emission linewidth, underlying broadening mechanisms, and some key physical properties of various light sources. As seen, most of the bands fall entirely or partially in the transparency window of lithium niobate, which spans from the UV to the mid-IR (MIR) (0.4-5 \(\mu m\))21,22. This provides an opportunity of applying the current LNOI MRR circuits to those various uses. For all of them, the 2 pm FWHM spectral resolution of the current MRR devices is adequate to quantitatively measure the line broadening effects, from which the source temperature can be retrieved. In Supplementary Section S3, we discuss several simple models for the temperature retrieval in those applications.

The important metrics for temperature retrieval in environmental sensing are the linewidth broadening sensitivity to the temperature change, \(d(\Delta \lambda _{obs})/dT\), and the temperature retrieval resolution, \(\Delta T_{ret}=2\ pm/|d(\Delta \lambda _{obs})/dT|\), based on the 2-pm resolution of the MRR spectrometer. In the HCL model, we calculated the sensitivity which ranges from 0.0005 to 0.02 pm/K, yielding a resolution between 106 and 3952 K. While the resolution appears limited, Fig. 7 demonstrates that temperature changes in our HCL are typically hundreds to thousands of Kelvin per 2 mA lamp current step (minimum step is 1 mA). This large change relative to \(\Delta T_{ret}\) ensures our method remains applicable in the HCL temperature retrieval, as evidenced by the discernible linewidth broadening in Fig. 6. In higher-temperature regimes, the linewidth becomes less sensitive to temperature increases, as Doppler broadening dominates (\(\Delta \lambda _G\propto \sqrt{T}\)), resulting in a sensitivity that approximately scales as \(d(\Delta \lambda _{obs})/dT\sim T^{-1/2}\). However, such temperatures exceed typical operating conditions of HCL and are more relevant in fusion or astrophysical plasmas, where Stark broadening may enhance sensitivity.

In real-world wildfire detection scenarios, additional techniques may be needed to enhance solar background suppression beyond the laboratory bandpass filters. Initial passive detection of potassium D lines is performed using a combination of bandpass filters and the high-resolution MRR filter. Upon detection, active fluorescence sensing can be triggered, in which a pulsed UV laser excites free potassium atoms in the plume44,45. Time-gated detection captures only the resulting fluorescence at D line wavelengths, effectively rejecting continuous solar photons during off-gate intervals. The fluorescence signal is subsequently analyzed for spectral linewidth broadening in the 11–17 pm range (see Table 1), arising from Doppler and collisional effects, and for temperature retrieval in the 1000–2500 K range (see Table 1). These spectral characteristics, along with the precise temporal correlation between the excitation pulses and detected emissions, enable robust discrimination of fire-induced potassium fluorescence from background noise.

Furthermore, different applications have different measurement requirements not only on wavelength bands and resolution, but also the scanning range and speed. For the thermo-optic tuning, the tunability is given by59

Here, \(\Delta P_h\) is the change of the applied electric power for the heater and \(\Delta \lambda _{res}\) is the resultant shift in the resonant wavelength. \(L_{h}\) is the heater length. R is the ring radius. \(\Delta T\) is the temperature change of the heated ring waveguide. \(\partial n_{eff}/\partial T\) is the thermal-optic coefficient. \(\Delta T/\Delta P_{h}\) is the heater efficiency (i.e., thermal resistance).

In Eq. (9), the thermal-optic coefficient can be calculated by computing the relevant transverse mode properties using finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations. In our case, \(\partial n_{eff}/\partial T=1.79\times 10^{-5}\) K\(^{-1}\). The heater efficiency can be efficiently adjusted by changing the distance between the heater and the MRR waveguide. Figure 8 and its inset plot the heater efficiency versus distance derived from Fig. 2 and Eq. (9), and \(n_{eff}\) as a function of the temperature from the FDTD simulation.

The heater efficiency depends on the distance and thermal conductivity of the cladding material between the heater and waveguide, and the heater’s electrode material composition and geometry14,30. It is, however, nearly independent of the waveguide geometry, suggesting that the above result can serve as a good design guideline empirically across a broad range of wavelengths. For field deployment, GHz-rate electro-optic tuning could supplement thermal tuning to more effectively compensate for ambient thermal fluctuations (\(\ll\)1 kHz), albeit with a moderate increase in optical loss. Finally, despite the periodicity in the MRR’s resonant lines, the spectral measurement range can exceed the FSR by adding a tunable coarse filter with bandwidth narrower than FSR to block cross-talk interference from unwanted channels.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a high-precision emission spectrometer using a chip-integrated microring resonator on thin-film lithium niobate, which measures the K lines from a HCL plasma source with a FWHM of 2 pm. We have also presented a temperature retrieval method to estimate the source temperature based on the precise linewidth measurement. Because of lithium niobate’s wide transparency window, this device and temperature retrieval techniques could find broad applications in wildfire detection, atomic physics research, fusion reactor diagnostics, and astrophysics observations. With high resolution and chip integration, our device offers high performance, low cost, and robustness for airborne and spaceborne missions.

Also, our technique allows the integration of multiple MRR filters on the same chip, to simultaneously measure multiple emission lines. In this demonstration, we have measured the K doublet lines using a single chip but individually. In the future, one can couple the outputs of cascaded MRRs each to a single photon detector and sweep their resonance all at the same time, for hyper-spectral measurement. Potential challenges include thermal crosstalk between MRRs and tuning synchronization. Thermal crosstalk can be mitigated by optimizing MRR spacing, while synchronized tuning under a common voltage source is achieved via an auxiliary circuit that individually biases each MRR heater, establishing resonator-specific operating voltages. Another prospect is to integrate other optical components on the same chip, such as WDM, quantum frequency converters, optical parametric amplifiers, and single photon detectors, to realize complex functions with exceptional SWaP parameters and operation robustness60,61,62,63.

Methods

MRR fabrication

The MRR chip is fabricated from a commercial 300-nm thin film X-cut LiNbO\(_3\) with 4.7-\(\mu m\) SiO\(_2\) and 0.5-mm Si. For lithography, we spin 800-nm HSQ resist on the sample. The MRR pattern is written by a 150 keV E-beam lithography tool (EBL, Elionix ELS-BODEN 150) with 1 nA current. The HSQ is then developed by TMAH for 30s and the sample is etched by an ion beam etching tool (IBE, INTLVAC Nanoquest) for 180 nm depth. We use RCA-I to clean the redeposition of LN and BOE 6:1 to clean the remaining HSQ. The sidewall angle (\(82^{\circ }\)) and top width are checked by a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Nova NanoSEM). Then we add 1.5-um SiO\(_2\) cladding by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD, PlasmaPro NGP80).

Next, PMMA 495A11 (in large thickness for easy lift-off) and PMMA 950A4 (for high resolution writing pattern) with a total thickness of 1.5 \(\mu m\) is spun as a resist. A 50 keV EBL (Elionix ELS-LS50) is used to write the heater pattern. By using IPA:MIBK 1:1 as the resist developer, the pattern is created and 10/100 nm Ti/Pt is deposited by electron-beam deposition (E-beam evaporator, Angstrom Ultra High Vacuum Nexdep). Finally, the lift-off by Remover PG for 30 minutes removes the remaining resist and produces the zigzag metal heater pattern.

Calibration methods

The calibration system is shown in Fig. 9.

Calibration setup. PZT: piezoelectric transducer. BS: beam splitter. FPC: fiber polarization controller. PD: photodiode. AWG: arbitrary waveform generators. TEC: thermoelectric cooler. The blue, green, and black lines represent the SMF, the 780 nm lens fiber, and the electric wires, respectively. The coarse and fine scan waveforms are monitored by the oscilloscope.

The calibration laser should have high resolution and minimal fluctuation. A tunable laser (New Focus TLB-6700) is used, with its output split by a beam splitter (BS). One output path is directed to a wavemeter (Msquared SolsTis) to monitor the wavelength scanning over time. The other path passes through a fiber polarization controller (FPC) and is coupled into the input port of the micro-ring resonator (MRR) using a 780 nm lens fiber (OZ OPTICS LTD). Light with a wavelength aligned to the resonator’s resonance wavelength is filtered and directed to the drop port. The MRR is mounted on a stage with a thermoelectric cooler (TEC) that maintains a thermal environment of \(300\pm 0.003\) K. The filtered light is coupled into another 780 nm lens fiber, connected to a single-mode fiber (SMF), and detected by an amplified photodiode (PD, Thorlabs PDA100A2), which converts the optical signal to an electrical signal. The electrical signal is then monitored by an oscilloscope (Tektronix DPO 2004B) to find the resonance peaks. Simultaneously, the laser performs coarse wavelength scanning using an internal DC motor, with the wavelength monitored by the wavemeter and the corresponding electrical signals observed on the oscilloscope.

The fine scanning of the laser wavelength can be achieved through the external frequency modulation of a piezoelectric transducer (PZT) driver using channel 1 (CH1) of an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG, Rigol DG4162). The synchronized electrical signal from CH2 can be monitored via an oscilloscope.

To assess the resolution and stability of the laser, we compared its coarse and fine scanning capabilities as shown in Fig. 10. For coarse scan, we set a minimum scan range of 10 pm and a minimum scan speed of 10 pm/s. The minimum scan step resolution reaches 0.5 pm, but the fluctuation was as large as 1 pm in the forward scan and up to 2 pm in the reverse scan.

The wavemeter reading of the wavelength scan for laser coarse scan by an internal DC motor and fine scan by external frequency modulation of a PZT. The top subfigure shows the coarse scan, with 10-pm minimum scan range. For fine scan, ramp (0.1-pm minimum range) and square waveforms are applied to obtain laser step resolution and fluctuation, respectively. The bottom subfigure presents the fine scan with a ramp waveform applied (51-pm range) used to characterize the MRR linewidth.

In the fine-scan mode, a ramp waveform with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 2 mV and a period of 2 s is applied from the AWG to the PZT, producing an output wavelength range of 0.1 pm. A square waveform from the AWG is also used as input signal to monitor the fluctuation of laser when the output wavelength remains constant. By analyzing the ramp and square scan data points, we determine that the laser resolution reaches 0.01 pm with a fluctuation of 0.03 pm.

Here, we also present the methods of characterizing the MRR chip. For coarse scan, a low laser input power − 15 dBm is given to prevent skewing of the resonance peak due to optical bistability30,64, which may give inaccurate linewidth measurements. The scan range is set to 2 nm with a speed of 1 pm/ms, starting at a wavelength of 766.1 nm. The time interval between starting time and the resonance peak time is measured on oscilloscope and converted to wavelength by the scan speed.

For the fine scanning, a peak-to-peak voltage of 2.2 V is applied to the laser PZT, resulting in a laser output wavelength range of 51 pm. The frequency of AWG is set to 500 mHz (2-second period), therefore the scanning speed is 0.051 pm/ms. By setting percent of the maximum PZT voltage to 50\(\%\) we can adjust the fine scan range near the resonance wavelength located by the coarse scan, as shown in Fig. 10. Since the PD output voltage is linear to the incident light power, its FWHM can be found by directly reading the voltage at half of the maximum voltage value. By checking time interval on oscilloscope we can convert time to wavelength to obtain the resonance wavelength and linewidth precisely with accuracy ±0.03 pm.

Using the above characterization procedure, we calibrated two parameters prior to the experiment: the initial resonance wavelength \(\lambda _{res}(V_0)\) and the tunability \(\Delta \lambda _{res}/\Delta P_h\). These values were used as input parameters in a MATLAB code, which mapped the applied voltage to the corresponding resonance wavelength during the experiment, as described by Eq. (2).

In addition, the stability of the thermal environment of the chip stage controlled by the TEC was evaluated. Based on Eq. (9), a \(\pm 3\) mK temperature fluctuation of the stage yields a resonance wavelength fluctuation \(\Delta \lambda _{res}=\pm 0.02\) pm. In the calculation, we used \(\lambda _{res}=766.5\) nm, \(n_{eff}=1.98\), \(L_h=140\) \(\mu m\), \(R=40\) \(\mu m\), \(\partial n_{eff}/\partial T=1.79\times 10^{-5}\) K\(^{-1}\), and \(\Delta T=\pm 3\) mK.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Amici, S., Wooster, M. J. & Piscini, A. Multi-resolution spectral analysis of wildfire potassium emission signatures using laboratory, airborne and spaceborne remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 1811–1823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2011.02.022 (2011).

Bonaventura, N., Jakobsen, P., Ferruit, P., Arribas, S. & Giardino, G. The near-infrared spectrograph (NIRSpec) on the James Webb Space Telescope: V. Optimal algorithms for planning multi-object spectroscopic observations. Astron. Astrophys. 672, A40. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202245403 (2023).

Greenhouse, M. The James Webb space telescope: Mission overview and status. In 2016 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO.2016.7500940 (2016).

Fantz, U. Basics of plasma spectroscopy. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 15, S137–S147. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/15/4/S01 (2006).

Sharma, S. et al. Diverse organic-mineral associations in Jezero crater. Mars. Nature 619, 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06143-z (2023).

Morton, D. C. Atomic data for resonance absorption lines. III. Wavelengths longward of the Lyman limit for the elements hydrogen to gallium. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 149, 205–238. https://doi.org/10.1086/377639 (2003).

Falke, S., Tiemann, E., Lisdat, C., Schnatz, H. & Grosche, G. Transition frequencies of the \(d\) lines of \(^{39}{\rm K}\), \(^{40}{\rm K}\), and \(^{41}{\rm K}\) measured with a femtosecond laser frequency comb. Phys. Rev. A 74, 032503. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.74.032503 (2006).

Vodacek, A. et al. Remote optical detection of biomass burning using a potassium emission signature. Int. J. Remote Sens. 23, 2721–2726. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431160110109633 (2002).

Waigl, C. F., Prakash, A., Stuefer, M., Verbyla, D. & Dennison, P. Fire detection and temperature retrieval using EO-1 Hyperion data over selected Alaskan boreal forest fires. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 81, 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2019.03.004 (2019).

Dennison, P., Charoensiri, K., Roberts, D., Peterson, S. & Green, R. Wildfire temperature and land cover modeling using hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. Environ. 100, 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2005.10.007 (2006).

Tipler, P. A. & Llewellyn, R. A. Modern physics 6th edn. (W. H Freeman Co, 2012).

Ding, S. et al. A high-density and high-confinement tokamak plasma regime for fusion energy. Nature 629, 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07313-3 (2024).

Jaspers, R. J. E. et al. A high etendue spectrometer suitable for core charge exchange recombination spectroscopy on ITER. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 10D515. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4732058 (2012).

Zheng, S. N. et al. Microring resonator-assisted Fourier transform spectrometer with enhanced resolution and large bandwidth in single chip solution. Nat. Commun. 10, 2349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10282-1 (2019).

Pohl, D. et al. An integrated broadband spectrometer on thin-film lithium niobate. Nat. Photonics 14, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0529-9 (2020).

Yuan, S., Naveh, D., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Xia, F. A wavelength-scale black phosphorus spectrometer. Nat. Photonics 15, 601–607. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-021-00787-x (2021).

Grotevent, M. J. et al. Integrated photodetectors for compact Fourier-transform waveguide spectrometers. Nat. Photonics 17, 59–64 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Silicon photonic spectrometer with multiple customized wavelength bands. Photonics Res. 12, 1016–1023 (2024).

Graydon, O. On-chip spectroscopy. Nat. Photonics 12, 189–189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-018-0149-9 (2018).

Liapis, A. C., Gao, B., Siddiqui, M. R., Shi, Z. & Boyd, R. W. On-chip spectroscopy with thermally tuned high-Q photonic crystal cavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 021105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4939659 (2016).

Zhu, D. et al. Integrated photonics on thin-film lithium niobate. Adv. Opt. Photonics 13, 242. https://doi.org/10.1364/AOP.411024 (2021).

Boes, A. et al. Lithium niobate photonics: Unlocking the electromagnetic spectrum. Science 379, eabj4396. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj4396 (2023).

Jin, M., Chen, J.-Y., Sua, Y. M. & Huang, Y.-P. High-extinction electro-optic modulation on lithium niobate thin film. Opt. Lett. 44, 1265. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.44.001265 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Efficient parametric frequency conversion in lithium niobate nanophotonic chips. OSA Continuum 2, 2914. https://doi.org/10.1364/OSAC.2.002914 (2019).

Zhu, X. et al. Twenty-nine million intrinsic Q-factor monolithic microresonators on thin-film lithium niobate. Photonics Res. 12, A63. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.521172 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Carbon-dioxide absorption spectroscopy with solar photon counting and integrated lithium niobate micro-ring resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 171103. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0045869 (2021).

Zhang, J., Sua, Y. M., Hu, Y., Ramanathan, J. & Huang, Y.-P. Oxygen a-band absorption spectroscopy with solar photon counting and lithium niobate nanophotonic circuits. Front. Remote. Sens. 3, 1064244. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsen.2022.1064244 (2022).

Sarmiento, L. F. et al. Comparing the emission spectra of U and Th hollow cathode lamps and a new U line list. Astron. Astrophys. 618, A118. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201832871 (2018).

Srećković, A., Dimitrijević, M. S. & Djeniže, S. Stark broadening in O III spectrum. Astron. Astrophys. 371, 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20010343 (2001).

Bogaerts, W. et al. Silicon microring resonators. Laser Photonics Rev. 6, 47–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201100017 (2012).

Pozar, D. M. Microwave Engineering 4th edn. (Wiley, 2012).

Boyajian, T. S. et al. Stellar diameters and temperatures. I. Main-sequence A, F, and G stars. Astrophys. J. 746, 101. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/746/1/101 (2012).

Goebel, D. M., Becatti, G., Mikellides, I. G. & Lopez Ortega, A. Plasma hollow cathodes. J. Appl. Phys. 130, 050902. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0051228 (2021).

Loudon, R. The quantum theory of light (OUP Oxford, 2000).

Wang, H., Gould, P. L. & Stwalley, W. C. Long-range interaction of the 39K (4s)+ 39K (4p) asymptote by photoassociative spectroscopy. I. The g-pure long-range state and the long-range potential constants. J. Chem. Phys. 106, 7899–7912. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.473804 (1997).

Fridman, A. A. Plasma Chemistry 1st edn. (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Saloman, E. B. & Sansonetti, C. J. Wavelengths, energy level classifications, and energy levels for the spectrum of neutral neon. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 33, 1113–1158. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1797771 (2004).

Sansonetti, J. E. & Martin, W. C. Handbook of basic atomic spectroscopic data. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 34, 1559–2259. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1800011 (2005).

Olivero, J. & Longbothum, R. Empirical fits to the Voigt line width: A brief review. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 17, 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4073(77)90161-3 (1977).

Griem, H. R. Principles of plasma spectroscopy. In Cambridge Monographs on Plasma Physics (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Numano, M. Criteria for local thermodynamic equilibrium distributions of populations of excited atoms in a plasma. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 43, 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4073(90)90020-7 (1990).

Drawin, H. W. Validity conditions for local thermodynamic equilibrium. Z. Physik 228, 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01397532 (1969).

Tallents, G. J. An Introduction to the Atomic and Radiation Physics of Plasmas (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Weng, W., Brackmann, C., Leffler, T., Aldén, M. & Li, Z. Ultraviolet absorption cross sections of KOH and KCl for nonintrusive species-specific quantitative detection in hot flue gases. Anal. Chem. 91, 4719–4726. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00203 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Potassium upconversion violet light generation under two-color two-photon excitation to 4D, 6S level. Eur. Phys. J. D 76, 88. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjd/s10053-022-00411-9 (2022).

Amici, S., Spiller, D., Ansalone, L. & Miller, L. Wildfires temperature estimation by complementary use of hyperspectral PRISMA and thermal (ECOSTRESS & L8). J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 127, e2022JG007055. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JG007055 (2022).

Creely, A. J. et al. Overview of the sparc tokamak. J. Plasma Phys. 86, 865860502. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022377820001257 (2020).

Greenwald, M. et al. A new look at density limits in tokamaks. Nucl. Fusion 28, 2199. https://doi.org/10.1088/0029-5515/28/12/009 (1988).

Kado, S., Suzuki, K., Iida, Y. & Muraki, A. Doppler and Stark broadenings of spectral lines of highly excited helium atoms for measurement of detached recombining plasmas in MAP-II divertor simulator. J. Nucl. Mater. 415, S1174–S1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2011.01.048 (2011).

Griem, H. R. & Barr, W. L. Spectral line broadening by plasmas. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 3, 227–227 (1975).

Neyskens, P. et al. The temperature and chronology of heavy-element synthesis in low-mass stars. Nature 517, 174–176. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14050 (2015).

Burdonov, K. et al. Laboratory evidence for an asymmetric accretion structure upon slanted matter impact in young stars. Astron. Astrophys. 642, A38. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202038189 (2020).

Sahal-Bréchot, S. & Elabidi, H. Stark broadening for Br VI and Kr V-VII lines in hot star atmospheres. Astron. Astrophys. 652, A47. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140729 (2021).

Frémat, Y. et al. Gaia Data Release 3: Properties of the line-broadening parameter derived with the Radial Velocity Spectrometer (RVS). Astron. Astrophys. 674, A8. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202243809 (2023).

Padovani, P. et al. Active galactic nuclei: What’s in a name?. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 25, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00159-017-0102-9 (2017).

Akylas, A. & Georgantopoulos, I. Distribution of the coronal temperature in Seyfert 1 galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 655, A60. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202141186 (2021).

Foschini, L. On the broadening of emission lines in active galactic nuclei. Astron. Astrophys. 385, 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20020231 (2002).

Kollatschny, W. & Zetzl, M. The shape of broad-line profiles in active galactic nuclei. Astron. Astrophys. 549, A100. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201219411 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Highly efficient thermo-optic tunable micro-ring resonator based on an lnoi platform. Opt. Lett. 45, 6318–6321. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.410192 (2020).

Sayem, A. A., Cheng, R., Wang, S. & Tang, H. X. Lithium-niobate-on-insulator waveguide-integrated superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 151102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5142852 (2020).

Prencipe, A. et al. Wavelength-sensitive superconducting single-photon detectors on thin film lithium niobate waveguides. Nano Lett. 23, 9748–9752. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c02324 (2023).

Lu, J. et al. Ultralow-threshold thin-film lithium niobate optical parametric oscillator. Optica 8, 539. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.418984 (2021).

Stone, J., Westly, D., Moille, G. & Srinivasan, K. On-chip Kerr parametric oscillation with integrated heating for enhanced frequency tuning and control. Opt. Lett. 49, 3118. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.523704 (2024).

Almeida, V. R. & Lipson, M. Optical bistability on a silicon chip. Opt. Lett. 29, 2387–2389. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.29.002387 (2004).

Acknowledgements

YD thanks Zhaohui Ma and Zhan Li for training and helps on nanofabrication. This work was supported in part by NASA (Grant No. 80NSSC22K0286). Device fabrication was performed at Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC), City University of New York (CUNY), Columbia Nano Initiative (CNI), Columbia University, and Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. and Yu.H. wrote the main manuscript. Y.D. fabricated the MRR chip, conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed experimental data, and performed theoretical and numerical calculations. Y.M.S., Yo.H., and P.G. contributed to the conceptualization of the project. Y.M.S. and S.K. assisted in resource preparation and project coordination. J.Z. provided guidance on chip fabrication and experimental design. X.L. helped on the chip fabrication process. Y.M.S. and Yu.H. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Y., Sua, Y.M., Kumar, S. et al. Chip-integrated spectroscopy capable of temperature retrieval. Sci Rep 15, 30437 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14754-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14754-x