Abstract

Off-the-road (OTR) waste tires of heavy mining dump trucks have devastating environmental effects. They are also a reliable source of some valuable raw materials, which could be returned to the manufacturing process by recycling. Pyrolysis is a promising and eco-friendly approach for recycling big, heavy tires. This paper aims to use a laboratory-scale reactor to investigate the pyrolysis process and analyze the recycled pyrolytic yields of OTR ultra-heavy mining waste tires in large Iranian open pit mines. After developing the pyrolyzer set up in a laboratory, eight popular tire brands used in open-pit mine dump truck fleets were selected and collected as the sampling population. Smaller samples were prepared by cutting and downsizing them into small pieces. Each tire brand was then processed under pyrolysis conditions with operating parameters including the batch weight of 2.5 kg, the maximum temperature of 600 °C, and residence time varying from 120 to 173 min based on the specific tire brand. The percentage of the main products are fuel oil (31–36%), non-condensable gases (10–13%), carbon black (31–38%), and steel wire (18–25%). The results show that the thermochemical decomposition of OTR mining waste tire samples occurs within a temperature range of 300–400 °C, proceeding through three distinct degradation phases (oil, char, and gas). As the temperature increased, due to secondary cracking reactions in volatile matter, the oil yield fell while gas yield rose in the same order. Analysis of the produced pyrolytic oil and char suggests that both products have potential applications as fuels. Moreover, the FESEM images of recycled carbon black from all studied samples show the coalesced nanoparticles, sugar fabric, and porous media due to the desulfurization process. This paper’s outputs could primarily be applied for developing any pilot or industrial plant for tire recycling in Iran and economic analysis of investment return rate as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultra-heavy dump trucks are extensively used in large open-pit mining operations and rely on massive off-the-road (OTR) tires with limited lifespans. These tires constitute a significant portion of operational costs, up to one-third in some cases, and are a major source of solid waste in mining operations1,2,3. Globally, around 800 million OTR tires are discarded annually1,4with mining trucks being responsible for 15–20% of this volume5. Nowadays, the removal of mining OTR tires is an environmental concern. Due to their large size (2–4 m in diameter, over 3 tons in weight) and complex chemical structure6,7,8these tires are difficult to transport, nearly non-biodegradable, and pose serious environmental risks if improperly disposed4,9,10. In many regions, OTR tires are left, stockpiled, or sometimes openly burned (Fig. 1), leading to soil and groundwater contamination and the release of hazardous pollutants and greenhouse gases11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

(a) Truck waste tire pollution on the shoreline20 and, (b) leaving of OTR waste tires in one of the Iranian mines (taken by the corresponding author).

To address these challenges, environmentally sustainable recycling methods are essential. Several approaches have been developed for managing OTR waste tires, including rubber powder production, tire retreading, landfilling, and pyrolysis21. Among these, pyrolysis has emerged as a particularly promising solution, offering waste reduction, resource recovery and decreasing air pollution. This thermochemical process breaks down tire components into valuable byproducts such as fuel, carbon black, and gas, making it a key technology for the sustainable management of ultra-heavy OTR waste mining tires. Based on the heterogeneity in tire compositions across manufacturers, the primary research question is whether differences in the brand of ultra-heavy OTR mining waste tires significantly influence the yield of final products when processed under identical thermal conditions. Therefore, this study investigates the potential of pyrolysis technology for managing OTR waste tires in mining applications.

Literature review

OTR waste mining truck tires are primarily composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, making up about 80% of their total mass, and they contain significant energy potential22. Due to their high carbon content, OTR exhibit a considerable calorific value of approximately 30–45 MJ/kg21,23. When effectively managed, this energy can be transformed into electricity, thermal energy, and other usable forms, thereby enhancing a nation’s energy portfolio and decreasing reliance on costly fossil fuels24. Furthermore, utilizing OTR mining waste tires as a resource not only helps in mitigating environmental impacts but also offers economic benefits, supporting the broader goal of sustainable development. Conversely, improper management of tire disposal and elimination can lead to disastrous environmental consequences.

Over the past two decades, stockpiles of scrapped passenger car tires (PCT) have exceeded those of OTR mining truck waste tires. However, with the development of the mining industry in recent years, the waste tires of ultra-heavy mining dump trucks have also significantly increased, posing a significant environmental challenge.

According to the literature, numerous researchers have investigated the pyrolysis process of waste tires from light and semi-heavy vehicles, including cars, motorcycles, bicycles, buses, trucks, and agricultural machinery21,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. The yield and quality of pyrolysis products depend on both the type of tires and the specific conditions of the pyrolysis process34. Accordingly, the chemical composition of waste tires significantly impacts the distribution of pyrolysis products. Pyrolysis primarily involves the breakdown of organic components, particularly rubber, which consists of natural rubber (NR), styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR), and butadiene rubber (BR)35. Each type of rubber exhibits unique pyrolysis behaviors. As a result, variations in the content and distribution of these rubber components across different types of waste tires lead to distinct pyrolysis characteristics and product distributions36. There are some studies about the effect of tire type on pyrolysis products. Ucar et al. investigated the differences in the aromatic content of pyrolysis oil derived from passenger car tires and truck tires at 550 °C. Their findings showed that the aromatic content in passenger car tires pyrolysis oil (41.54 vol%) was significantly higher than that in truck tires pyrolysis oil (15.41 vol%), mainly due to the higher styrene-butadiene rubber content in passenger car tires37. Similarly, Lopez et al. reported comparable results, noting that the aromatic content in passenger car tires and truck tires pyrolysis oils was 43.7 wt% and 33.4 wt%, respectively, corresponding to styrene-butadiene rubber contents of 29.6 wt% in passenger car tires and 0 wt% in truck tires38.

Numerous studies have investigated the effects of critical parameters on pyrolysis yields. These parameters primarily include reactor type, temperature, heating rate (HR), residence time (RT), and sample size29,30,32,39,40,41. Due to the low thermal conductivity of tires, the furnace (reaction chamber) and heat transfer system are the most critical components in the pyrolysis process. Advancements in technology have enabled researchers to investigate a wide variety of reactor designs, including pressurized and vacuum, continuous and batch, catalytic and non-catalytic, as well as fluidized and fixed bed systems, to optimize pyrolysis performance31,42. Reactor type can be effective on the quality and quantity of pyrolysis yields. Palos et al. indicated that the reactor type had no significant effect on char yield while the char composition was highly dependent on reactor configuration43. A direct comparison between fixed and moving bed reactors has been carried out by Mavukwana et al. They concluded that due to faster heat transfer, the cracking of pyrolysis products in moving bed reactors is higher than in fixed beds44.

Temperature is the most important parameter for the decomposition and depolymerization of rubber in the pyrolysis process. Generally, with increasing temperature, gas yield rises, whereas the amount of char and oil products declines45. Sanchís et al. conducted a pyrolysis process on truck tires to investigate the effect of temperature on product quality. They found that the oil yield peaked at 500 °C, and observed that increasing the temperature led to a significant rise in the synthesis of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX) in the liquid phase39. Additionally, researchers often select a temperature range of 500 to 600 °C to maximize char production. Hita et al. reported that char yield typically ranged from 35 to 45% between 500 °C and 600 °C46. Similarly, another study conducted pyrolysis experiments at varying temperatures (550–800 °C), finding that the maximum char yield of 45% occurred at 550 °C47.

The heating rate is another parameter significantly associated with heat and mass transfer in tires, affecting the critical pyrolysis temperature, the residence time, and the subsequent secondary reactions48. In the secondary reaction, long carbon chains initially break down during pyrolysis, releasing carbon and hydrogen molecules. In the next stage, these molecules undergo rearrangement and cross-linking to form various hydrocarbons in both liquid and gas phases15.

Generally, a higher heating rate accelerates the pyrolysis process but reduces the carbon content in char. In other words, a lower heating rate is advantageous for maximizing char and oil yields, while a higher heating rate increases gas yield49. Consequently, many studies have utilized heating rates ranging from 5 °C/min to 30 °C/min for the pyrolysis of waste tires50,51,52.

Residence time is the next critical factor in the pyrolysis process because it significantly enhances secondary reactions and increases the yield of pyrolysis gases. Studies investigating the effect of RT on pyrolysis have predominantly been conducted over durations of 30 to 120 min, typically using feedstock quantities of less than 1 kg45. Extended RT is often related to lower heating rates at a certain temperature, which enhances the devolatilization process47. Moreover, the surface area of pyrolyzed char slightly increases with prolonged RT and higher temperatures, even without the use of activating agents53.

The importance of feedstock particle size in the pyrolysis process is very high because it strongly impacts the heat transfer rate, pyrolysis completion time, mass transfer efficiency and energy consumption of the process54. Due to the rise of surface area for effective heat transfer in the particle, smaller tire particles are typically preferable because they facilitate more efficient and uniform heat transfer among the feedstocks55,56. From a scientific research perspective, the yields of pyrolysis products vary significantly with particle size. Particle size has minimal impact on product yields in fast pyrolysis (heating rate of 500 °C/min and residence time < 2 s). In contrast, smaller particles can enhance product yields during slow pyrolysis with lower heating rates. These particles require less pyrolysis time than larger ones but consume more energy57. According to the literature, particle size varying from 0.5 to 60 mm was used for the pyrolysis processes15.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, existing studies primarily focus on the pyrolysis of light (CPT) and semi-heavy waste tires, with little attention given to ultra-heavy mining waste tires. Notably, no studies have examined the impact of tire type, particularly across various brands of OTR ultra-heavy mining waste tires, on pyrolysis products. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to evaluate and simulate the pyrolysis process of several brands of OTR ultra-heavy mining waste tires using a new gravitational feeding laboratory-scale pyrolyzer. Moreover, this study conducts a preliminary evaluation of the recovered products, including carbon black and pyrolytic oil, to assess their potential for future utilization in high-value applications.

Materials and experimental

Materials

Off-the-road (OTR) ultra-heavy mining waste tires

Steel radial OTR tires are the standard choice for mining dump trucks, valued for their great strength, cut and heat resistance, and load-bearing capabilities. Engineered with advanced technology, these tires offer unmatched durability and extended service life, making them indispensable for the rigorous operational demands of the mining industry58. The tiers are made up of different main parts, including tread, steel cord belts, inner liner, steel cord carcass, and bead (Fig. 2)4,58,59. The detailed functions of each component are beyond this research’s scope and are comprehensively covered in the literature60. A critical tire component is the bead, which fixes the tire to the truck’s steel rim. The bead contains wire cores, some of which have a square cross-section designed to provide adequate strength to withstand external loads. In tire recycling plants, the first step is the separation of the bead from the tire body, typically using a “Debeader” device. Removing the bead wire before cutting and shredding produces a cleaner final product and reduces wear on the shredder’s moving parts.

Structural diagram of an OTR mining tire59.

Generally, tires can be classified into three categories based on their compositions and applications59: Cut-resistant tires that are designed to withstand damage from sharp objects, such as rocks, debris, or metal shards, which can cause cuts or punctures during operation. This property is critical in construction sites, off-road terrains, and mining operations. The second type is heat resistance, designed to perform efficiently under high-temperature conditions, such as prolonged high-speed driving or operations in hot climates. Excessive heat buildup in tires can lead to wear, reduced grip, or even blowouts. The last type is called cut-and-heat-resistant tires. This type of tire combines cut and heat resistance and is specifically engineered to perform in extreme conditions where sharp object impacts and high temperatures are common. These tires are particularly useful in demanding industries like mining, construction, and heavy transportation, where vehicles are exposed to rugged terrains and intense operational heat.

Data collection and sampling

The data collection method employed in this study is regarded as the most critical and time-consuming phase. A comprehensive database of Iranian ultra-heavy mining truck waste tires was developed to prepare feedstock for the laboratory-scale pyrolyzer. Initially, tire landfills at numerous open-pit mines were visited and inspected, with their distribution illustrated in Fig. 3. It should be noted that these mines are the largest open-pit mines in Iran or even globally, including Southern zone (Gol Gohar iron mines No. 1 to 5), Sarcheshme zone (Sarcheshme copper mine, Jalal Abad iron mine, and Sharbabak copper mine), Central Iranian zone (Northern Anomaly iron mine, Chahgaz iron mine, Mishodan iron mine, Chadormalu iron mine, and Mehdiabad lead and zinc mine), Northwestern zone (Angoran lead and zinc, Zarshouran gold and Soungoun copper) mines, and Northeastern zone (Sangan iron ore complex mines).

In the subsequent phase, 11 mines were selected as target sites due to the higher end-of-life (EOL) rates of worn OTR waste mining tires at these locations. Details of these target mines are provided in Table 1. For laboratory analysis, samples with sufficiently large dimensions were obtained from selected types of OTR waste mining tires.

Additionally, the database includes information on the number of active dump truck fleets, the volume of OTR waste tire stockpiles, the most common tire brands, and the annual EOL rate of OTR waste tires. For instance, the Gol Gohar mining complex operates the largest fleet of mining dump trucks in Iran and maintains a massive stockpile of OTR waste tires, estimated at approximately 4,000 tons. Figure 4 illustrates a portion of this stockpile.

In this phase, the number of active dump trucks in the studied mines was scientifically estimated, and the EOL rate of OTR waste tires was assessed. Field studies revealed that 515 dump trucks of various capacities are currently operating in the targeted mines, producing approximately 8,570 tons of OTR waste tires annually. This volume is sufficient to sustain a large-scale recycling plant with a daily capacity of 20 tons. Additionally, preliminary field estimates indicate that around 15,030 tons of OTR waste mining tires are currently stockpiled at these mines (Table 1).

According to the literature, no previous study has compiled such comprehensive data on OTR waste tire stockpiles, popular brands, and annual EOL rates for OTR tires. Notably, the data collection process for this study took over a year.

The thermal degradation characteristics of various OTR mining tire brands differ significantly due to component variations1. To ensure representative samples for the laboratory pyrolysis reactor, eight commonly used OTR mining tire brands were selected: Michelin-XDR2-27R49 (S1), Triangle-TB526S**27R49 (S2), Bridgestone-VERP-27R49 (S3), Goodyear- 4SL**27R49 (S4), Michelin-XDT-E4T-18R33 (S5), Bridgestone-Vsteel-18R33 (S6), Good Year-4 A+-24R35 (S7), Magna-E-4**-30R51 (S8). A total of 24 tire rings (circa 3 tons per ring) from these brands were collected from the target mines and transported to tire laboratory at Isfahan University of Technology (IUT) for analysis.

The tires had to be downsized and chipped into 5 × 5 × 5 cm pieces for the laboratory-scale pyrolysis tests. However, due to the complex multi-layered structure, large dimensions of OTR waste tires, and the unavailability of debeading and cutting devices, the cutting process was extremely challenging (Fig. 5). As shown in this figure, the cutting was performed manually using a cutter-off wheel.

Following the cutting process, a novel method for separating tire components was developed due to the unavailability of a shredder. This method involved immersing tire segments in liquid nitrogen. A styrofoam chamber was prepared, and over 500 L of liquid nitrogen were poured into it. Depending on the tire’s thickness and brand, the separation process required one to three immersion stages.

To minimize liquid nitrogen consumption, the tire segments were first pre-cooled in a freezer set to -50 °C for approximately 12 h before immersion in liquid nitrogen (Fig. 6). After immersion, the segments were removed individually and manually crushed with a hammer to separate the steel and cotton fibers from the rubber, thoroughly.

The separation process was successfully conducted for all samples. Under heavy impacts, the tire’s solid structure broke down, resulting in the separation of over 99% of the rubber. Figure 7 illustrates the different components of the Michelin-XDR2-27R49 waste tire after the separation process, including chipped and crumbed rubber granules, scraped steel wires, steel beads, and cotton fibers.

To ensure compatibility with the laboratory pyrolysis reactor, properly sized feed material in the form of chipped and crumbed rubber granules was prepared for all eight tire brands (Fig. 8). Each pyrolysis batch requires 2–2.5 kg of feed, with a maximum granule size of 5 centimetres, ensuring optimal performance of the reactor.

Development of an experimental setup

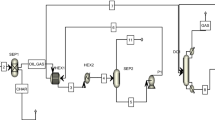

In this study, a laboratory-scale reactor was designed and manufactured to simulate the recycling process of OTR waste mining tires closely. One of the most critical technical steps in this process was selecting the appropriate reactor type, given the variety of pyrolyzers available. Reactors can be classified based on several criteria, including the method of thermal energy supply, operational efficiency, and the mechanism for feeding raw materials (feedstocks) into the reactor. The latter criterion, in particular, determines how granules are transported within the reactor. To date, three main types of reactors have been developed: pneumatic, mechanical, and gravity-based (column type) reactors61. In addition to the reactor type, other factors such as feeding mechanism, reactor volume, internal temperature and pressure, sample size, and the presence of a stirrer were considered to optimize the design. For a laboratory-scale setup and the specific nature of the materials being studied (OTR waste mining tires), a controlled feeding operation was essential. Consequently, a discontinuous (batch) feeding approach was considered most suitable. A gravity-based column-type reactor was chosen to meet these requirements for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with batch transport. Figure 9 presents a picture and schematic of the constructed atmospheric reactor, developed at the Advanced Process Simulation and Control Laboratory of Isfahan University of Technology (IUT).

The stirred pyrolyzer is a commonly used mechanical bed reactor. In this device, a stirrer is employed to mix the feedstock, ensuring efficient heat transfer without generating heat directly. Instead, heat is supplied through the reactor wall. Char produced during the process is collected at the bottom of the reactor. The reactor operates similarly to a fixed-bed reactor, with the main difference being the mobility of the feedstock.

The central component of the reactor is the heating chamber, which is equipped with a sluice at its upper end. Based on the sample size used in each batch (approximately 2 to 2.5 kg) and the optimum expected yield of recycled materials, the internal volume of the reactor was designed to be five liters. For enhanced safety, the reactor chamber features a double-walled construction. At the top of the chamber, a sluice with a diameter of 10 centimeters was designed to facilitate material feeding, provide access for maintenance, and enable periodic cleaning of the interior. The energy required for the pyrolysis process is supplied by electronic converters mounted on the exterior of the chamber. These converters efficiently transform electrical energy into heat, thereby raising the temperature inside the chamber to the desired levels for pyrolysis. The main specifications of the developed laboratory-scale reactor have been given in Table 2.

Among the pyrolysis products, the solid and liquid yields are particularly important1. To maximize their quantities, a systematic and controlled process for cooling and storing condensate is essential. Therefore, a condenser is positioned adjacent to the heating chamber to convert condensable gases into hydrocarbon condensates.

Since the recycling process for OTR mining waste tires is relatively unexplored, the reactor must be capable of operating under moderately high pressure and temperature conditions. Therefore, the reactor’s ability to withstand pressures up to 10 bar and temperatures up to 700 degrees Celsius is essential. The control panel unit is an essential component of the reactor, containing controllers and actuators for managing pressure, temperature, and engine operation. It provides real-time pressure and temperature data throughout the pyrolysis process.

Experimental procedure

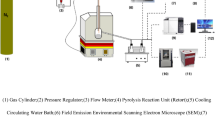

After reducing the tire particles to a maximum size of 5 cm, their characteristics were analyzed through proximate and ultimate analysis, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). Following the characterization of the waste tires, pyrolysis experiments were conducted using a custom-designed pyrolysis reactor for all samples. After obtaining the products, amounts of the pyrolysis oil and char were analyzed and calculated using the gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method according to ASTM 6370-23 standard.

The pyrolysis gas products were analyzed using a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatograph according to ASTM D2504. Olefins and paraffins were identified using a flame ionization detector (FID) equipped with an HP-Plot/Q capillary column, while carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) were quantified using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) equipped with a TDX-01 capillary column.

Proximate and ultimate analysis

Studying the physical and chemical properties of waste tires is crucial for evaluating their pyrolysis behavior. The chemical composition of tires varies significantly depending on their types and applications. Generally, tires are composed of rubber, carbon black, steel wire, fillers, and various accelerators, including reinforcing agents, vulcanizing agents, and antioxidants7,48.

Rubber is the primary component of light tires, accounting for approximately 45% of their total composition, and is responsible for providing elasticity. Tire rubber is divided into natural rubber (NR) and synthetic rubber (SR). The proportions of NR and SR differ across tire types. Truck tires typically have a higher NR content to withstand heavier loads and long-distance travel, while passenger car tires contain a higher proportion of SR48. It has been demonstrated that natural rubber creates high mechanical resistance and improves the thermal stability of tires14. Carbon black is another key component, enhancing tire elasticity, wear resistance, and providing coloration. Fillers contribute to the strength and structural support of the tire. Additionally, natural rubber, a primary ingredient, offers strong mechanical resistance and thermal stability, enabling tires to maintain their properties over extended periods and under demanding conditions14. Proximate analysis was performed to determine the moisture, ash content, volatile matter, and fixed carbon, following standard ASTM procedures: ASTM D3173, ASTM D3174, and ASTM D3175, respectively. The fixed carbon content was calculated indirectly by subtracting the combined values of moisture, volatile matter, and ash from 100%.

Ultimate analysis was conducted to quantify the elemental composition, including carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), sulfur (S), and oxygen (O). The respective ASTM standard methods employed were ASTM D3178 for carbon and hydrogen, ASTM D3179 for nitrogen, and ASTM D4239 for sulfur, while oxygen content was determined by difference. All elemental analyses were conducted using a LECO CHN600 elemental analyzer. Results of proximate and ultimate analyses of all studied tire brands are tabulated in Table 3.

TGA analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is a widely employed thermal analysis technique that monitors changes in the mass of tire samples as they are subjected to a controlled heating program, either at a constant rate or under isothermal conditions, in a defined atmosphere. TGA is frequently utilized to investigate thermal stability, decomposition kinetics, and the compositional characteristics of materials62. This study conducted TGA measurements using a TGA55 thermogravimetric analyzer (equipped with TA instruments) according to ASTM D6370-23 standard method, which features a mass resolution of 0.0001 mg and a temperature accuracy of 0.01 °C. Approximately 10 ± 0.5 mg of each sample was evenly distributed across the crucible surface to promote uniform heat transfer and minimize temperature gradients. The TGA results obtained for all samples exhibited a similar trend from room temperature to 600 °C. Therefore, the thermographic curve (TG), differential thermogravimetric (DTG) curves undergo continuous mass changes, along with differential thermal analysis (DTA) for sample number 1 (S1) are presented in Fig. 10.

It shows the initial phase the volatilization of oils and processing additives, or any other element with low molar weight and low boiling temperature till 200 °C, the weight loss reached 1.5% attributed to humidity. Consequently, due to the decomposition of the polymeric material, the release of organic vapors, and the formation of carbonaceous residues, the most significant mass loss occurred in the temperature range of 250 °C to 550 °C.

Pyrolysis experiments

Pyrolysis experiments were carried out for each sample. To do that, it was essential to determine the operation parameters. Several studies have explored the impact of residence time (RT) on pyrolysis outcomes. Most research has examined RTs between 30 and 120 min, typically using feedstock quantities under one kilogram45,50,63. However, larger feedstocks, such as 2.5 kg samples or OTR mining tires, generally require extended residence times (173 min in this study). Additionally, studies have shown that increasing RT and temperature slightly enhances the surface area of pyrolyzed char, even without using an activating agent. Residence time also plays a significant role in influencing the yield and characteristics of pyrolysis oil. In general, shorter residence times are preferable for maximizing oil production53,64.

One of the significant parameters on pyrolysis products is temperature21,34,65. Therefore, to determine the optimal thermal degradation temperature for the OTR mining waste tire pyrolysis, this study conducted tests at four different temperature stages: (1) the reactor was initially set to 350 °C, maintaining a uniform temperature throughout the pyrolyzer chamber. Despite an increase in internal pressure due to the burning of tire granules, the pressure dropped after 50 min, and the stirrer stopped due to incomplete pyrolysis. At this point, the samples had turned into an adhesive material, sticking to the chamber walls. (2) at 400 °C, similar outcomes occurred; pressure dropped after 75 min, and the stirrer stopped. The primary products at this stage were dimers and trimers. (3) with the reactor temperature set to 500 °C, the pyrolysis process proceeded without interruption for 173 min, with complete discharge of recycled products. At this temperature, a balanced yield of products was achieved by controlling pressure (2 bar), the outlet valve, and condensate discharge timing. (4) At 600 °C, due to the existence of secondary cracking reactions, the production of carbon black and oil decreased while gas yield increased.

The objective was to maintain a high reactor temperature to ensure the effective thermal decomposition of tire waste. However, high temperatures and residence times can convert oil into gas, reducing oil yield66. As a result, the optimal temperature to maximize the yields of oil, gas, and char was determined to be around 500 °C.

Table 4 summarizes various studies examining the pyrolysis of waste tires across different temperature ranges to evaluate yield outcomes. It should be noted that the experimental parameters, such as reactor type, particle size, heating rate, and feedstock residence time, vary across studies depending on the specific experimental conditions. In most studies, the optimal temperature is selected to maximize production efficiency. However, in the developed reactor, the temperature was chosen with a primary focus on minimizing environmental impacts. The lab-scale reactor utilized in this study operates within a temperature range of 350 to 600 °C, achieving an oil production yield of 31–36%, depending on the brand of the tires.

After conducting the pre-tests, the overall procedure for the main experiments was established. During the primary pyrolysis experiments, the samples were placed into the heating chamber, and all outlets were sealed. The pre-heating process was initiated by setting the temperature to 250 °C, leading to an increase in pressure within the reactor chamber. This pressure rise was closely monitored via the device control panel. Once the pressure reached 2 bar, the outlet valve was opened to release the gases and prevent delays in the testing process, allowing the condensation process to commence.

Following the outlined pyrolysis procedure, all prepared samples were tested. However, due to the variability in the chemical composition of OTR waste mining tires, the total duration of the pyrolysis process varied. The decomposition mechanism of polymers during pyrolysis occurs in a stepwise manner, influenced by the surface nature of the reaction. Specifically, heat progressively impacts the outer shell of the rubber granules, with the pyrolysis process advancing in a layer-by-layer fashion. Simultaneously, stirring the granules during the reaction displaces pyrolyzed materials, exposing the next polymer layer to heat. This dynamic increases the contact surface area between the material and the heat source, accelerating the pyrolysis process.

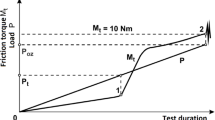

It is observed that the pressure within the reactor chamber changes throughout the pyrolysis process, as illustrated in Fig. 11. An increase in pressure at the beginning of the process indicates a proper reaction, resulting in the formation of condensable and gases. When the operating pressure of the chamber reached 2 bar (the first peak), the outlet valve connected to the condenser was manually opened, causing a subsequent pressure drop. The desulfurization and degassing process occurred at this stage, facilitated by evacuating volatile gaseous materials. Notably, the stirrer remained inactive during this phase. Following this, the reactor’s stirrer was activated. The opening of the outlet gas valve allowed the pressure within the condenser and the reactor chamber to stabilize. Under these conditions, the second pressure peak was observed approximately 15 min into the process. Pressure fluctuations persisted throughout the pyrolysis process, with a general downward trend signaling the completion of the reaction and the consumption of raw materials.

As the outer layers of the granules broke down due to heat, the resulting gases were released from the chamber, leading to periodic pressure drops. This pressure cycle decreased and subsequent gas generation continued as successive polymer layers underwent pyrolysis. The process concluded with the production of carbon black.

Overall, the initial rise in pressure after the start of the pyrolysis process signifies the effectiveness of the reaction, as it demonstrates the generation of condensable and gases.

In addition to pressure, another criterion for evaluating the pyrolysis process and determining its completion was the change in the shape, height, and color of the gas flare produced during the process (Fig. 12). As shown in the figure, at the beginning of the process (Fig. 12a), the flare was low in height and exhibited a blue color due to the production of Methane. As the process progressed, hydrogen and light hydrocarbons were released in the gaseous phase within the reactor and subsequently mixed with other gases, leading to an increase in system pressure and a distinct shift in flare color to yellow (Fig. 12b). This change signify the production of char in the reactor. Furthermore, an increase in internal gas production (rising pressure) within the chamber resulted in a higher flare height (Fig. 12c). The flare height gradually decreased as the pyrolysis process neared completion, eventually extinguishing once the reactor’s product yields were fully consumed (Fig. 12d–f).

Pyrolysis tests were conducted on all prepared samples, and the pyrolysis durations of the studied samples are presented in Fig. 13. According to the figure, the pyrolysis duration of Michelin-XDR2-27R49 was longer than that of the other samples, likely due to its specific composition. It is worth noting that the operation time for semi-industrial and industrial scales extends to 480 min per process. This increase is attributed to the larger dimensions of the reactor and the higher feeding rate61.

Results and discussion

Three main pyrolysis product yields were obtained from all the studied samples in three distinct phases: char (carbon black), oil, and gas. The product yields were measured and presented in Fig. 14. The distribution of pyrolysis products of the studied samples is roughly the same, with the solid phase being predominant, followed by the liquid phase, and the non-condensable gas being the least. According to the figure, the yields of the primary products obtained in the laboratory were fuel oil (31–36%), non-condensable gases (10–13%), and carbon black (31–38%). When scrutinized in this figure, it can be viewed from three perspectives: initially, the relationship between residence time and condensate (oil) yield indicates that Goodyear-4SL (S4) and Bridgestone-VERP (S3) show moderate residence times (147 and 145 min) accompanied by relatively high condensate yields (36%). Michelin-XDR2 (S1), with the longest residence time (173 min), has one of the lowest condensate yields (31%). Also, Michelin-XDT-E4T-18R33 (S5), with the shortest residence time (120 min), shows high condensate (36%) yield. It can be concluded that longer residence times tend to decrease condensate (oil) yield, mainly due to secondary cracking of vapors into gas, which is consistent with reports of some researchers40,63,69.

Moreover, regarding residence time and gas yield, it was observed that longer residence times (as seen in S1 and S4) resulted in higher gas yields. This is because extended residence time in the reactor allows for more extensive cracking, leading to an increased production of gaseous pyrolysis products.Shorter residence time tires (Michelin-XDT-E4T-18R33 (S5)); also maintain gas at 11%, but with a higher condensate level. So, gas yield slightly increases with residence time, consistent with extended vapor cracking. It can be explained that longer residence time of the tires within the reactor facilitates sufficient heat transfer, thereby promoting a higher extent of pyrolysis. Conversely, limited residence time restricts heat absorption, resulting in incomplete or less efficient pyrolysis48,70,71.

However, no strong correlation was observed between residence time and the yields of solid phase, as these components are primarily influenced by the composition of the tire material rather than the thermal decomposition behavior. In contrast, residence time has a significant impact on the distribution of volatile products. Shorter residence times tend to favor higher yields of condensate (pyrolysis oil) by facilitating the rapid removal of vapors before secondary cracking occurs48,72. Overall, while the yields of steel and carbon black remain relatively constant, optimizing residence time is crucial for maximizing oil recovery and controlling gas output in tire pyrolysis processes.

Analysis of the three-phase product yield

From an economic perspective, recycled gas is the most cost-effective product for use as a source of technological heat, especially after purification for electricity generation. Raw char is also relatively inexpensive; however, it can be converted into carbon black, widely reused in manufacturing off-the-road (OTR) mining tires (as an additive), when upgraded. Oil is the most valuable yield globally among pyrolysis products, provided it is not utilized as a liquid fuel or diesel61. In recent years, tire pyrolysis has gained significant attention for the production of carbon black, which has a wide range of applications, including rubber manufacturing, paints, inks, pigments, graphite, bitumen, asphalt, concrete, pipes, and conveyor belts45,73. Therefore, this study primarily focuses on characterizing the char and oil product yields.

After the pyrolysis process, the resulting char and oil products were collected for analysis. Figure 15 illustrates the recycled carbon black obtained from Michelin XDR2-27R49 (S1) tires as a representative example.

The char produced during the pyrolysis of waste tires mainly consists of the carbon black originally added to the tire formulation to enhance its anti-abrasive properties. The quality of the char significantly impacts the overall economic feasibility of the tire pyrolysis process28. Carbon black serves as a critical reinforcing filler in tire manufacturing, providing functions such as coloring, reinforcement, electrical and thermal conductivity, and UV resistance. It also plays a vital role in determining the physical and mechanical properties, as well as the processing characteristics of rubber compounds14,34.

However, the carbon black generated in the process is often polluted with a small amount of volatile non-carbon substances like sulfur and inert gases, ash content, moisture, etc74. The presence of such disturbing elements reduces the quality of carbon black and has an impact on its porous structure75,76. Therefore, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) was utilized for all samples to study the structural composition of the recycled carbon black. Figure 16 shows micrographs of recycled carbon black of the Michelin-XDR2-27R49 sample (S1). In this study, we do our best to remove gas pollutants using the desulfurization and degassing processes. For this purpose, gas evacuation frequency was increased to provide enough time for the gas to release and then condense to become a liquid. In other words, as the residence time decreases, the pressure drops sharply and the sulfur gases are dramatically evacuated from the carbon black. Macroporous (pore size > 50 nm)77 illustrates the rapid escape of volatile gases like hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur from carbon black particle bodies, by reducing the residence time in the reactor (Fig. 16b–d). This enhances the char’s porosity and specific surface area, making it more effective for use as an adsorbent because provide ample space for contaminants to be adsorbed78,79. Furthermore, the images shown in Fig. 16e and f reveal that the recycled carbon black derived from waste ultra-heavy mining tires exhibits a sugar-like texture and a nanostructured morphology, which contributes to its ultra- high surface area, well- distributed por structure, and high efficiency at lower doses.

Oil components GC/MS analysis

Even though the main objective is to produce char, the hydrocarbon condensates, which are liquids collected during the cooling of pyrolysis vapors, are also considered valuable. These are essentially pyrolysis oils or fuel oils, which can be used as alternative fuels or feedstocks in diesel engines and chemical industries. In other words, while the experiment is primarily focused on obtaining carbon black, the liquid by-products (fuel oils) generated during the process also have economic and practical value. Figure 17 shows the hydrocarbon condensates (liquid) of the studied samples, which are dark brown color.

To investigate the main chemical composition of the fuel oil, an Agilent 7890B-5977B gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system, according to ASTM D8274, was employed for all studied samples of pyrolysis oil. A 0.5 mL oil sample was diluted with 10 mL of ethanol to prepare the analysis solution. Approximately 1 µL of the diluted solution was injected into the GC-MS system using a sampling needle. Separation was performed using an RTX-VMS capillary column with a maximum operating temperature of 230 °C. The analysis was conducted under the following conditions: the injector split ratio was set at 20:1, and helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 2.0 ml/min. The temperature program for the GC oven started at an initial temperature of 50 °C, held for 3 min, followed by a ramp to 230 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, and held at the final temperature for 15 min. The chemical components of the pyrolysis oil were identified by comparing their mass spectra with entries in the NIST Mass Spectrometry Library. Based on the test, the main ingredients of the fuel oil of Michelin-XDR2-27R49 (S1) have been illustrated in Fig. 18.

As can be seen in this figure, the amount of benzene in the liquid yield is higher than other components, comprising 22.84%, suggesting a high aromatic content typical of tire pyrolysis oil. Cyclohexene accounts for 8.8%, a significant fraction of cyclic alkenes. Limonene (5.65%) and Naphthalene (5.5%) are also present. Limonene is a known product of natural rubber pyrolysis, and naphthalene is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. Xylene (4.36%) and Butene (1.3%) represent lighter hydrocarbons. Pentene is only 2.14%, suggesting a minor role among light alkenes. The high content of benzene, xylene, and naphthalene indicates that the oil is rich in aromatic hydrocarbons, which are valuable as industrial feedstock but may require refining for fuel use due to toxicity. The presence of Limonene can be leveraged as a high-value chemical product. The large “other” category suggests that further GC-MS analysis could help identify additional components for better characterization.

Some researchers have reported similar findings, while others have observed differing results. Díaz et al. performed pyrolysis on waste mining tires and reported that the resulting oil primarily consisted of 41.4% butene, 25% benzene, 10% hexane, and 8.43% pentene80. Similarly, Martin et al. analyzed pyrolysis products using chromatographic techniques and found the liquid fraction to contain 19.8% benzene, 16% butene, 13.6% hexane, and 6% pentene31.

Based on findings from both the current study and existing literature81,82,83,84 on the liquid fraction of pyrolysis products, it is evident that the chemical composition varies among different types of tires. This variability is likely attributable to differences in the material formulations used by various tire manufacturers.

Conclusions

In this study, the pyrolysis products of OTR ultra-heavy mining waste tires have been investigated in a laboratory scale. For this end, initially, it has been conducted a characterization analysis of eight popular brands of waste tire particles, including elemental and TGA analyses. According to the TGA results, the most significant mass loss happened in 250 to 550 °C for the studied samples. Secondly, a new lab-scale batch-type stirred reactor with gravitational feeding was developed to study the pyrolysis characteristics of the eight brands of OTR ultra-heavy mining truck waste tires for the first time. To prepare the feedstock of the reactor, a comprehensive database of the waste tires from the haulage fleets of large Iranian open pit mines was developed. After performing the pyrolysis process on the prepared samples (optimal temperature of 500 °C), three product yields were obtained in three phases: solid (char and metal), oil, and gas. It can be concluded that the distribution of pyrolysis products of the studied samples is roughly the same, with the solid phase being predominant, followed by the liquid phase, and the non-condensable gas being the least. In other words, the type of tire does not have a great effect on the amount of pyrolysis product yields. The composition of the pyrolysis products is influenced by both the type of rubber and the residence time. As a result, the produced char exhibits a high specific surface, and the condensate demonstrates high energy due to its elevated benzene content in spite of its toxicity. For further investigation, a field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) was carried out for recycled carbon blacks of all samples. It has been revealed that a porous and nanostructured medium which suitable for adsorbents. Moreover, a gaseous chromatography test using a mass spectrometer (GC-MS) was performed to study the composition of the produced condensates and find that the amount of benzene is more than the other components and recycled oil required refinement.

According to the findings of this study, the pyrolysis process can be utilized for the recycling of OTR waste ultra-heavy mining tires without causing harmful effects on the environment. Finally, it should be noted that the limitation of this study is its small-scale lab setup, a narrow selection of tire samples (8 brands), and basic analysis of pyrolysis products. Further research with semi-industrial scale systems and advanced characterization is recommended in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gao, N. et al. Tire pyrolysis char: processes, properties, upgrading and applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 93, 101022 (2022).

Noakes, M. et al. Cost Estimation Handbook for the Australian Mining Industry. (1993).

Pascual, R., Román, M., López-Campos, M., Hitch, M. & Rodovalho, E. Reducing mining footprint by matching haul fleet demand and route-oriented tire types. J. Clean. Prod. 227, 645–651 (2019).

Mayer, P. M. et al. Where the rubber Meets the road: emerging environmental impacts of tire wear particles and their chemical cocktails. Sci. Total Environ. 927, 171153 (2024).

Oyola-Cervantes, J. & Amaya-Mier, R. Reverse logistics network design for large off-the-road scrap tires from mining sites with a single shredding resource scheduling application. Waste Manage. 100, 219–229 (2019).

Amari, T., Themelis, N. J. & Wernick, I. K. Resource recovery from used rubber tires. Resour. Policy. 25, 179–188 (1999).

Sienkiewicz, M., Kucinska-Lipka, J., Janik, H. & Balas, A. Progress in used tyres management in the European union: A review. Waste Manage. 32, 1742–1751 (2012).

Abnisa, F. & Wan Daud, W. M. A. Optimization of fuel recovery through the Stepwise co-pyrolysis of palm shell and scrap tire. Energy. Conv. Manag. 99, 334–345 (2015).

Hejna, A. et al. Waste tire rubber as low-cost and environmentally-friendly modifier in thermoset polymers – A review. Waste Manage. 108, 106–118 (2020).

Goodyear Goodyear Off-The-Road Engineering Data. (2021).

Singh, R., Chen, Y., Gulliver, J. S. & Hozalski, R. M. Leachability and phosphate removal potential of tire derived aggregates in underground stormwater chambers. J. Clean. Prod. 395, 136428 (2023).

Kalbe, U., Krüger, O., Wachtendorf, V., Berger, W. & Hally, S. Development of leaching procedures for synthetic turf systems containing scrap tyre granules. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 4, 745–757 (2013).

Zinatloo-Ajabshir, S. et al. Novel rod-like [Cu(phen)2(OAc)]·PF6 complex for high-performance visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of hazardous organic dyes: DFT approach, Hirshfeld and fingerprint plot analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 350, 119545 (2024).

Rowhani, A. & Rainey, T. Scrap tyre management pathways and their use as a Fuel—A review. Energies 9, 888 (2016).

Doja, S., Pillari, L. K. & Bichler, L. Processing and activation of tire-derived char: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 155, 111860 (2022).

Superior Watershed Partnership (SWP). (2022). https://superiorwatersheds.org/2024-hp-projects/pdf/10-Tons-of-Great-Lakes-Debris-Removed-Flyer.pdf.

Howarth, D. F. & Rowlands, J. C. Quantitative assessment of rock texture and correlation with drillability and strength properties. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 20, 57–85 (1987).

Gołasa, P., Lenort, R., Wysokiński, M. & Baran, W. & Bieńkowska-gołasa, W. Concentration of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union. Metal 23, (2014).

Tsimnadis, K., Kyriakopoulos, G. L. & Leontopoulos, S. Practical improvement scenarios for an innovative Waste-Collection recycling program operating with mobile green points (MGPs). Inventions 8, 80 (2023).

EGLE. Michigan Scrap Tire Program Study Finds Opportunities in New Markets. (2020). https://www.recycle.com/latest/michigan-scrap-tire-program-study-finds-opportunities-in-new-markets.

Afash, H., Ozarisoy, B., Altan, H. & Budayan, C. Recycling of tire waste using pyrolysis: an environmental perspective. Sustainability 15, 14178 (2023).

Grigoratos, T., Gustafsson, M., Eriksson, O. & Martini, G. Experimental investigation of tread wear and particle emission from tyres with different treadwear marking. Atmos. Environ. 182, 200–212 (2018).

Barbosa, A. R. et al. A contribution for an optimization of the polishing quality of stone slabs: simulation and experimental study using a single-head polishing machine. In International Conference on Stone and Concrete Machining (ICSCM) 3, (2015).

Mentes, D., Tóth, C. E., Nagy, G., Muránszky, G. & Póliska, C. Investigation of gaseous and solid pollutants emitted from waste tire combustion at different temperatures. Waste Manage. 149, 302–312 (2022).

Babu, B. V. & Chaurasia, A. S. Heat transfer and kinetics in the pyrolysis of shrinking biomass particle. Chem. Eng. Sci. 59, 1999–2012 (2004).

Afrin, H., Huda, N. & Abbasi, R. Study on End-of-Life tires (ELTs) recycling strategy and applications. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 1200, 012009 (2021).

Alvarez, J. et al. Evaluation of the properties of tyre pyrolysis oils obtained in a conical spouted bed reactor. Energy 128, 463–474 (2017).

Lopez, G. et al. Waste truck-tyre processing by flash pyrolysis in a conical spouted bed reactor. Energy. Conv. Manag. 142, 523–532 (2017).

Yazdani, E., Hashemabadi, S. H. & Taghizadeh, A. Study of waste tire pyrolysis in a rotary kiln reactor in a wide range of pyrolysis temperature. Waste Manage. 85, 195–201 (2019).

Jiang, H. et al. Production mechanism of high-quality carbon black from high-temperature pyrolysis of waste tire. J. Hazard. Mater. 443, 130350 (2023).

Martín, M. T. et al. Influence of specific power on the solid and liquid products obtained in the Microwave-Assisted pyrolysis of End-of-Life tires. Energies 15, 2128 (2022).

Policella, M., Wang, Z., Burra, K. G. & Gupta, A. K. Characteristics of Syngas from pyrolysis and CO2-assisted gasification of waste tires. Appl. Energy. 254, 113678 (2019).

Díez, C., Sánchez, M. E., Haxaire, P., Martínez, O. & Morán, A. Pyrolysis of tyres: A comparison of the results from a fixed-bed laboratory reactor and a pilot plant (rotatory reactor). J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 74, 254–258 (2005).

Han, W., Han, D. & Chen, H. Pyrolysis of waste tires: A review. Polymers 15, 1604 (2023).

Evans, A. And E. R. The Composition of a Tyre: Typical Components5 (The Waste & Resources Action Programme, 2006).

Williams, P. T. & Besler, S. Pyrolysis-thermogravimetric analysis of tyres and tyre components. Fuel 74, 1277–1283 (1995).

Ucar, S., Karagoz, S., Ozkan, A. R. & Yanik, J. Evaluation of two different scrap tires as hydrocarbon source by pyrolysis. Fuel 84, 1884–1892 (2005).

Lopez, G., Olazar, M., Amutio, M., Aguado, R. & Bilbao, J. Influence of tire formulation on the products of continuous pyrolysis in a conical spouted bed reactor. Energy Fuels. 23, 5423–5431 (2009).

Sanchís, A. et al. The role of temperature profile during the pyrolysis of end-of-life-tyres in an industrially relevant conditions Auger plant. J. Environ. Manage. 317, 115323 (2022).

Pazoki, A., Ghasemzadeh, R. & Barikani, M. Pazoki1. Investigating the impact of process parameters on waste tire pyrolysis and characterizing the resultant Chars and oils. Int. J. Hum. Capital Urban Manage. 9, 509–520 (2024).

Čepić, Z. et al. Experimental analysis of temperature influence on waste tire pyrolysis. Energies 14, 5403 (2021).

Labaki, M. & Jeguirim, M. Thermochemical conversion of waste tyres—a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 9962–9992 (2017).

Palos, R. et al. Waste refinery: the valorization of waste plastics and End-of-Life tires in refinery units. A review. Energy Fuels. 35, 3529–3557 (2021).

Mavukwana, A. & Sempuga, C. Recent developments in waste tyre pyrolysis and gasification processes. Chem. Eng. Commun. 209, 485–511 (2022).

Zerin, N. H., Rasul, M. G., Jahirul, M. I. & Sayem, A. S. M. End-of-life tyre conversion to energy: A review on pyrolysis and activated carbon production processes and their challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 905, 166981 (2023).

Hita, I. et al. Opportunities and barriers for producing high quality fuels from the pyrolysis of scrap tires. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 56, 745–759 (2016).

Kumar Singh, R. et al. Pyrolysis of three different categories of automotive tyre wastes: product yield analysis and characterization. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 135, 379–389 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. A review on waste tires pyrolysis for energy and material recovery from the optimization perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 199, 114531 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. High-value utilization of waste tires: A review with focus on modified carbon black from pyrolysis. Sci. Total Environ. 742, 140235 (2020).

Banar, M., Akyıldız, V., Özkan, A., Çokaygil, Z. & Onay, Ö. Characterization of pyrolytic oil obtained from pyrolysis of TDF (Tire derived Fuel). Energy. Conv. Manag. 62, 22–30 (2012).

Bahri, M., Ghasemi, E., Kadkhodaei, M. H., Romero-Hernández, R. & Mascort-Albea, E. J. Analysing the life index of diamond cutting tools for marble Building stones based on laboratory and field investigations. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 7959–7971 (2021).

Shen, B., Wu, C., Wang, R., Guo, B. & Liang, C. Pyrolysis of scrap tyres with zeolite USY. J. Hazard. Mater. 137, 1065–1073 (2006).

Acosta, R., Tavera, C., Gauthier-Maradei, P. & Nabarlatz, D. Production of oil and Char by intermediate pyrolysis of scrap tyres: influence on yield and product characteristics. Int. J. Chem. Reactor Eng. 13, 189–200 (2015).

Tan, V. et al. Secondary reactions of volatiles upon the influences of particle temperature discrepancy and gas environment during the pyrolysis of scrap tyre chips. Fuel 259, 116291 (2020).

Haydary, J., Jelemenský, Ľ., Gašparovič, L. & Markoš, J. Influence of particle size and kinetic parameters on tire pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 97, 73–79 (2012).

Antoniou, N. & Zabaniotou, A. Experimental proof of concept for a sustainable end of life tyres pyrolysis with energy and porous materials production. J. Clean. Prod. 101, 323–336 (2015).

Oyedun, A., Lam, K. L., Fittkau, M. & Hui, C. W. Optimisation of particle size in waste tyre pyrolysis. Fuel 95, 417–424 (2012).

Mamani Israel, V. & Angélica, A. E. Assessing operational damage impact on mining tires (Case Study). J. Min. Environ. (JME). 15, 845–861 (2024).

GmbH. Off-The-Road Tires, Technical Data Book (Continental Reifen Deutschland GmbH, 2019).

Yokohama. Tire construction. (2024). https://www.yokohamaotr.com/otr/tires-101/otr-technology/tire-construction

Lewandowski, W. M., Januszewicz, K. & Kosakowski, W. Efficiency and proportions of waste tyre pyrolysis products depending on the reactor type—A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 140, 25–53 (2019).

Qi, J. et al. Study on pyrolysis of waste tires and condensation characteristics of products in a pilot scale screw-propelled reactor. Fuel 353, 129225 (2023).

Putra, A. E. E., Amaliyah, N., Syam, M. & Rahim, I. Effect of residence time and chemical activation on pyrolysis product from tires waste. J. Japan Inst. Energy. 98, 279–284 (2019).

Ma, S. et al. Effects of pressure and residence time on limonene production in waste tires pyrolysis process. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 151, 104899 (2020).

Menares, T., Herrera, J., Romero, R. & Osorio, P. Arteaga-Pérez, L. E. Waste tires pyrolysis kinetics and reaction mechanisms explained by TGA and Py-GC/MS under kinetically-controlled regime. Waste Manage. 102, 21–29 (2020).

Jahirul, M. I. et al. Transport fuel from waste plastics pyrolysis – A review on technologies, challenges and opportunities. Energy. Conv. Manag. 258, 115451 (2022).

Abdallah, R., Juaidi, A., Assad, M., Salameh, T. & Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Energy recovery from waste tires using pyrolysis: Palestine as case of study. Energies 13, 1817 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Effect of high heating rates on products distribution and sulfur transformation during the pyrolysis of waste tires. Waste Manage. 118, 9–17 (2020).

Wen, Y. et al. Insight into influence of process parameters on co-pyrolysis interaction between Yulin coal and waste tire via rapid infrared heating. Fuel 337, 127161 (2023).

Susa, D. J. H. Tire pyrolysis in a continuous screw reactor. Kautsch Gummi Kunstst. 6, 53–67 (2015).

Mui, E. L. K., Cheung, W. H. & McKay, G. Tyre Char Preparation from waste tyre rubber for dye removal from effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 175, 151–158 (2010).

Rofiqulislam, M., Haniu, H. & Rafiqulalambeg, M. Liquid fuels and chemicals from pyrolysis of motorcycle tire waste: product yields, compositions and related properties. Fuel 87, 3112–3122 (2008).

Jessica, N. Lizarazu. Haul Truck Tires Recycling. (2016).

Li, T. et al. Desulfurisation and Ash reduction of pyrolysis carbon black from waste tires by combined Fe3 + oxidation-flotation. J. Clean. Prod. 384, 135489 (2023).

Ayanoğlu, A. & Yumrutaş, R. Production of gasoline and diesel like fuels from waste tire oil by using catalytic pyrolysis. Energy 103, 456–468 (2016).

Yahya, M. A., Al-Qodah, Z. & Ngah, C. W. Z. Agricultural bio-waste materials as potential sustainable precursors used for activated carbon production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 46, 218–235 (2015).

Saleh, T. A. & Gupta, V. K. Processing methods, characteristics and adsorption behavior of tire derived carbons: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 211, 93–101 (2014).

Abram, J. C. Carbon Blacks as model porous adsorbents. Interface Sci. 27, 1–6 (1968).

Wang, J. & Man, H. L. S. Carbon Black: A Good Adsorbent for Triclosan Removal from Water. Water 14, (2022).

Díaz-Ferrán, G., Chudinzow, D., Kracht, W. & Eltrop, L. Solar-powered pyrolysis of scrap rubber from mining truck end-of-life tires – A case study for the mining industry in the Atacama desert, Chile. in 020003. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5067012 (2018).

Ding, K., Zhong, Z., Zhang, B., Song, Z. & Qian, X. Pyrolysis characteristics of waste tire in an analytical pyrolyzer coupled with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Energy Fuels. 29, 3181–3187 (2015).

Pyshyev, S. et al. Obtaining new materials from liquid pyrolysis products of used tires for waste valorization. Sustainability 17, 3919 (2025).

Sholokhova, A. Y. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the liquid fraction of car tire pyrolysis products by gas Chromatography–Mass spectrometry. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 94, 122–128 (2021).

Laresgoiti, M. et al. Characterization of the liquid products obtained in tyre pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 71, 917–934 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The current paper is a result of research project was funded by Iranian Minerals Production and Supply Co. (IMPASCO) under the contract number of 99.10255. Thus, financial support of IMPASCO and technical support of all mentioned mining companies during the data collection and field study is warmly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equal contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharifian, M., Farhadian, A., Almasiyeh, H. et al. Composition analysis of ultrapyrolytic recycled products from various brands of ultra-heavy mining truck waste tires. Sci Rep 15, 28692 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14755-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14755-w