Abstract

Exposure to lead has various health effects. Studies have correlated the δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism rs1800435 (ALAD1 and ALAD2) with blood lead levels, but the results have been inconsistent. This meta-analysis evaluated the associations between the rs1800435 and blood lead levels. Studies reporting the relationships of rs1800435 with blood lead levels were included. The sample size, means, and standard deviations were calculated. Subgroup analysis was performed on the basis of the presence or absence of lead exposure, age, sex, and geographic latitude of the investigated people. Twenty-seven studies with 17,344 individuals were included. There was no significant association between rs1800435 status and blood lead levels, either in the lead-exposed group (p = 0.280), nonlead-exposed group (p = 0.642), or overall analysis (p = 0.165). Among those exposed to lead, for people living at non-low latitudes (latitude > 30°), ALAD2 allele carriers had higher lead levels than ALAD1 homozygotes did (p = 0.001). For non-lead-exposed respondents, blood lead levels in male ALAD2 allele carriers demonstrated a marginally significant decrease compared with those in male ALAD1 homozygotes (p = 0.061). Lead exposure levels and the geographical latitude of long-term residence may modify the ALAD2-associated effects on blood lead concentrations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lead is a toxic element that is widespread in the human environment worldwide and has numerous industrial applications. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Toxicology Program (2012), lead remains an important environmental and public health problem, even though population exposure levels are decreasing. A statistically significant relationship was observed between pediatric sensorineural hearing loss and a blood lead level (BLL) greater than 10 µg/dL1. Cognitive deficits in children have been linked to environmental lead exposure, even when peak blood lead concentrations remain below 7.5 µg/dL2. Many scholars believe that there is no safe lead exposure threshold for children3. Low exposure levels can affect the physiology of multiple systems, including the hematopoietic, alimentary, immune, urinary (i.e., kidneys), peripheral and central nervous, and cardiovascular systems, especially in children4. Evidence has shown that certain genetic, environmental, and socioeconomic factors alter the effects of lead, indicating that individual susceptibility to lead may play an important role5,6. The interaction between lead and the heme synthesis enzyme δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) is a widely concerning problem.

Human ALAD is a single gene located on chromosome 9q34. Human ALAD encodes an enzyme that catalyzes two δ-aminolevulinate acid (ALA) molecules that condense into one porphobilinogen molecule, which is a precursor of heme, cytochromes, and other hemoproteins. Gene polymorphisms in ALAD may modify the toxicokinetics of lead. The most studied polymorphism is the ALAD G177C (dbSNP ID: rs1800435) variant located in exon 4. Rs1800435 results in two alleles, ALAD1 and ALAD2, and a polymorphic system with three enzymes: ALAD1-1, ALAD1-2, and ALAD2-2. Since ALAD2-2 homozygotes are rare, ALAD1 (ALAD1-1 homozygote) and ALAD2 (ALAD1-2 heterozygote and ALAD2-2 homozygote) are the most commonly used protein abbreviations. The changes in the amino acid sequence include the substitution of Lys59 in ALAD1 with Asn59 in ALAD2. Consequently, ALAD2 becomes more electronegative and increases its affinity for lead7,8. The overall impact of this change on the body is relatively complex. One plausible explanation is that the ALAD2 protein can bind more tightly to lead than ALAD1 does, allowing the lead to remain in the red blood cells and to be less readily available to other target cells, resulting in a decrease in lead toxicity9,10. However, the correlation between BLLs and rs1800435 has always been controversial. Some studies have reported that people who carry ALAD2 have higher BLLs than ALAD1 homozygous carriers do. However, some studies have reported no relationship between BLLs and the rs1800435 polymorphism. In 2007, two meta-analyses combined the results of these studies and reached similar conclusions. That is, rs1800435 could affect human susceptibility to lead, and ALAD2 allele carriers had higher BLLs than ALAD1 homozygous carriers did11,12.

Subsequently, numerous new research results and conclusions have been reported. Considering the important impact of lead on health and these new research results, in the present study, we reexamined previous research and incorporated later research data into a new meta-analysis to further explore the relationship between BLLs and rs1800435 status.

Methods

Study selection

The MEDLINE and Web of Science databases were searched on August 14, 2024, for studies published only in English. The references of the articles were also searched and read to find those that met the inclusion criteria. Common text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to lead and ALAD were used. The detail search strings were “Lead“[Mesh] and delta-Aminolevulinic Acid Dehydratase, “Lead“[Mesh] and δ-Aminolevulinic Acid Dehydratase, “Lead“[Mesh] and ALAD, rs1800435. No attempts were made to contact the authors.

Eligible articles included the following data: sample sizes, BLLs, arithmetic means, and standard deviations (SDs) for the ALAD1 and ALAD2 genotype participants. For SD, the article should either provide the SD directly or provide statistics from which the SD can be derived. Notably, some series of studies used the same population cohort and were included only once for calculation in this analysis, and the study with the largest sample size was prioritized for inclusion. The reasons for the inclusion or exclusion of this manuscript will be clearly explained in the results section.

Data extraction

Two data managers independently entered the data into an electronic database.

Lead-exposed individuals were defined as people with a clear, direct and continuous history of lead exposure, which is usually occupational lead exposure, and children with possible lead poisoning determined by elevated free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (FEP) levels. Nonlead-exposed individuals were defined as people without such a history of lead exposure or elevated FEP levels. The following information was extracted from the study: first author, publication year, whether the study included adults and/or children, identification of people with lead exposure, sex composition of the sample population (male, female, or both), Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), mean, and SD of the BLLs of ALAD1 homozygotes and ALAD2 carriers. The approximate latitudinal range of the area where the investigated population resided was extracted according to the literature. A low-latitude area generally refers to areas within 30° N–30° S (cities that cross the 30-degree latitude line are included), whereas a non-low-latitude area is the latitudinal zone above 30°.

The BLLs were converted to micrograms per deciliter (µg/dl). The procedure for converting the standard error (SE) to SD was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3, 2022. If the study provided subgroup stratum information that met the preset criteria, then each subgroup stratum was entered separately to effectively use the data. To minimize data entry errors, the two authors independently input data, which were then compared to determine whether there was a mistake.

If the cohort consisted of only children, the variable “age” was annotated as “children.” If it consisted of only adults, then “adults” was used. If the population was lead-exposed according to the definition above, the population was marked “yes” in the “exposed” column, including the children reported by Wetmur et al.13 in 1991. If non-lead-exposed, for example, the population simply resided nearby a lead factory or an office worker with no lead exposure at work, the variable “no” was given. “Both” represents the presence of two or more classes of variables in the study. For the “exposed” column, “both” means combined lead-exposed and non-lead-exposed populations within one group; the means and SDs of the BLLs in the ALAD1 and ALAD2 groups were composed of data from a mixed population queue consisting of lead-exposed and non-lead-exposed populations.

If the studies provided city or approximate geographical range information on where the respondents resided, the dimensional information was annotated as appropriate. Each “unknown” marker was explained in detail.

PROSPERO ID: CRD42024528422.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome of this study was the occurrence of a mean difference in BLLs between ALAD1 homozygotes (ALAD1-1) and ALAD2 carriers (ALAD1-2 and ALAD2-2). The results are presented as 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The fixed-effects model assumes homogeneity of the sizes of effects from different studies, whereas the random-effects model allows the effect sizes to vary as a random variable from a specified distribution with a certain mean and variance.

Heterogeneity was tested using the likelihood ratio test to compare the log-likelihoods and using the chi-square test and I2 measure of inconsistency. Significant heterogeneity was defined using the chi-square test, with a p value < 0.1. I2 values range from 0 to 100%, with higher values indicating a greater degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 0–25%, no heterogeneity; I2 = 25–50%, moderate heterogeneity; I2 = 50–75%, large heterogeneity; I2 = 75–100%, extreme heterogeneity)14. Subgroup analysis and regression analysis for the variables of lead exposure, age, sex, latitude, and HWE were performed to explore the causes of heterogeneity. If I2 was ≥ 50%, the random-effects model was used; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used.

For sensitivity analysis, a leave-one-out analysis was conducted by excluding individual studies one by one to test the robustness of the pooled effect size.

Publication bias was assessed using the methods proposed by Begg and Egger. STATA 15.1 software (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for the statistical calculations and image production.

Results

The search yielded 27 references5,13,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 which are summarized in Fig. 1. For the studies of Schwartz et al.19,40 the samples were from the same target population: Korean lead-exposed workers. BLLs were generally dynamic, but the individual genotypes did not change. Subsequent studies did not confirm or deny whether the same individuals participated in previous studies. Therefore, to prevent double counting of individual genetic data and reduce heterogeneity, in the present study, we included only the study with a larger sample size, which was Schwartz et al.19 In Kim et al.24 the data grouped on the basis of “lead workers” and “nonlead workers” did not provide data regarding BLLs in ALAD 1 homozygotes and ALAD 2 carriers in published available article. In Kim et al.’s24 study, both lead-exposed and nonlead-exposed individuals were included in the ALAD1 or ALAD2 groups, which means that the average and SD of BLLs in the ALAD1 and ALAD2 groups were composed of data from a mixed population queue consisting of occupational lead-exposed and nonoccupational lead-exposed populations. Although the exposure group comprised most of the sample including it in this meta-analysis’s lead-exposed group would increase heterogeneity. Thus, it was represented as “both” and counted in the overall data analysis.

For Hu et al.41, Wu et al.42, Weuve et al.29 and Fang et al.33 all cases were derived from the National Registry of U.S. Veterans. Except for the Fang et al.33 study, the other three studies included 2,280 men from the greater Boston area who were 21–80 years old. Studies that may contain duplicate human genetic data are summarized in Table 1.

One study included high-, medium-, and low-exposures groups on the basis of the exposure environment28. The BLLs of the high- and medium-exposure groups are similar to those of the occupational exposure groups in other studies. Workers in the moderate-exposure group, although not directly handling lead during their work, worked at the same workstations as those in the high-exposure group did. Therefore, in this study, this group was also classified as the exposure group. The BLL data of the low-exposure group were incomplete and not included in this study.

Another study also included high, low and control exposure groups on the basis of the exposure environment26. The BLLs of the high-exposure group are similar to those of the occupational exposure groups in other studies. The low-exposure group was composed of workers who were not in direct contact with lead oxides and not working in the same area as the high-exposure group. Although the BLLs of the low-exposure group were still significantly greater than those of the control group in the same study, they were similar to the BLLs of the non-lead-exposed population reported in other studies. The low-exposure group was divided into non-lead-exposed groups in this meta-analysis.

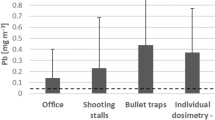

A total of 17344 individual genes and BLLs were included, and children accounted for 17.01% (2951) of the included data. The data are summarized in Table 2, and the corresponding geographic information is displayed in Fig. 2.

Overall analysis

According to the random-effects model, pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) analysis revealed high heterogeneity among the studies (WMD = − 0.318, 95% CI − 0.766 ~ 0.130, p = 0.165, I2 = 98.4%) (Fig. 3; Table 3). Subgroup analysis on the basis of age and exposure failed to eliminate heterogeneity. Regression analyses of age, exposure, sex, and latitude failed to identify the causes of heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses and regression modeling (Adj R-squared = 59.34%, I-squared_res = 98.47%, the model accounted for 59.34% of the heterogeneity, and there was still 98.47% residual heterogeneity) revealed that deviations from HWE partially accounted for the observed heterogeneity, as in a previous meta-analysis12. After the removal of studies that were not in HWE and those in which the state of HWE was unknown, the I2 was still at 98.6%. There were also no significant differences between rs1800435 and BLLs (lead-exposed group p = 0.887, non-lead-exposed group p = 0.617, or overall analysis p = 0.535). Therefore, a pooled analysis was conducted regardless of HWE.

The bias of Egger’s test (p = 0.357) did not show significant deviation, but both Begg’s rank correlation (z = − 4.29, p < 0.001) and Egger’s regression asymmetry tests (slope = − 0.902, 95% CI − 1.226 to − 0.579, p < 0.001) provided evidence of publication bias. The direction of bias implied that smaller studies disproportionately reported stronger ALAD2–BLL associations (e.g., Yun et al.35), whereas larger studies predominantly demonstrated minimal or null associations (e.g., Scinicariello et al.32).

Forest map for the meta-analysis, grouped by history of lead exposure. (a) High lead exposure. (b) Moderate lead exposure. (c) Low lead exposure. (d) Controls. (e) Uygur population group. (f) Han population group. (g) Non-Hispanic Whites. (h) Non-Hispanic Blacks. (i) Mexican Americans. (j) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients. (k) Individuals without ALS. CI: confidence interval, DL: DerSimonian‒Laird.

The sensitivity analysis of the overall analysis revealed that the combined effect estimate exhibited substantial robustness, as sensitivity analyses revealed consistent directional stability and nonsignificant findings following sequential exclusion of each included study.

The lead-exposed group

According to the random-effects model, there were no significant differences between the BLLs of ALAD2 allele carriers and the BLLs of ALAD1 homozygous allele carriers in the lead-exposed group (WMD = − 1.653, 95% CI − 4.656 ~ 1.349, p = 0.280, I2 = 82.6%) (Fig. 4; Table 3). Generally, low-latitude areas refer to those within 30°N–30°S, whereas other regions are considered to have non-low latitudes. Further subgroup and regression analyses conducted only on the data of the lead-exposed group revealed that latitude may be a source of heterogeneity and might be an important moderator variable. The model accounted for 44.50% (Adj R-squared) of the heterogeneity, and the heterogeneity decreased from 82.6 to 66.84% (I-squared_res). In the lead-exposed group, for individuals who lived in non-low-latitude areas (non-low-latitude subgroup), the ALAD2 allele carriers had higher BLLs than the ALAD1 homozygous carriers did (WMD = − 4.019, 95% CI − 6.466 ~ − 1.573, p = 0.001, I2 = 62.1%) (Fig. 4). For individuals living in low-latitude areas (low-latitude subgroup), there were no statistically significant associations between BLLs and rs1800435 status.

For the lead-exposed group, both Begg’s rank correlation test (z = 0.37, p = 0.714), Egger’s bias (p = 0.928) and linear regression (slope = − 1.97, 95% CI − 8.51 to 4.58, p = 0.522) indicated no statistically significant evidence of publication bias.

Sensitivity analysis indicated that the deletion of the literature by Siha et al.38 in 2019 had a significant effect on the lead-exposed group results of the meta-analysis. After deletion, the meta-analysis revealed that for the overall results of lead exposure (including data from both low-latitude and non-low-latitude regions), the blood lead concentration of ALAD2 carriers was greater than that of ALAD1 carriers (WMD = − 2.742, 95% CI − 5.061 ~ − 0.422, p = 0.021, I2 = 62.7%). However, the deletion had no significant impact on the results of the meta-analysis of the low-latitude and non-low-latitude subgroups. Siha et al.‘s38 investigation of Egyptian male workers occupationally exposed to lead revealed that ALAD2 allele carriers presented significantly lower BLLs than their ALAD1 counterparts did, with study characteristics fully satisfying the inclusion criteria of the present meta-analysis. Therefore, the data from this study were still retained, and the results of the meta-analysis that included these data were used in the conclusion.

The non-lead-exposed group

According to the random-effects model, there were no significant differences in the nonlead-exposed group (WMD = − 0.11, 95% CI − 0.59 ~ 0.36, p = 0.642, I2 = 99%) (Fig. 5; Table 3). In the nonlead-exposed group, latitude (low or non-low) did not influence the relationship between BLLs and rs1800435 status. However, in both adults and children, BLLs in male ALAD2 allele carriers were marginally significantly lower than those in male ALAD1 homozygotes (WMD = − 0.349, 95% CI − 0.016 ~ 0.713, p = 0.061, marginal significance, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 5). No positive results were found in the female population (WMD = − 0.567, 95% CI − 2.035 ~ 0.901, p = 0.449, I2 = 90.3%).

In the non-lead-exposed group, subgrouping analysis was performed on the basis of the sex of the population. (c)Low lead exposure.(d) Controls. (e) Uygur population group. (f) Han population group. (g) Non-Hispanic Whites. (h) Non-Hispanic Blacks. (i) Mexican Americans. (j) ALS patients. (k) Individuals without ALS. CI: confidence interval, DL: DerSimonian‒Laird.

The bias of Egger’s test (p = 0.278) did not show significant deviation. However, both Begg’s rank correlation (z = − 3.98, p < 0.001) and Egger’s regression asymmetry tests (slope = − 0.952, 95% CI − 1.373 to − 0.532, p < 0.001) indicated significant publication bias, suggesting selective underreporting of studies with null or inverse associations. This result is similar to the publication bias analysis results of the overall group. This bias likely inflated the apparent ALAD2-high BLL in small-sample studies (e.g., Yun et al.35, whereas larger studies predominantly reported near-null effects (e.g., Scinicariello et al.32. These findings may imply that the bias associated with smaller studies was due to the preferential publication of ‘positive’ findings. Conversely, larger, methodologically rigorous studies predominantly yielded null associations.

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis demonstrated the sustained robustness of the aggregated effect estimates in the non-lead-exposed population. The timing of maternal blood sampling at delivery in Yun et al.‘s35 study constituted a methodological distinction from other investigations with differing sampling windows. Nevertheless, post-exclusion sensitivity analyses demonstrated preserved effect magnitude stability, with recalculated estimates consistently residing within the initial CI ranges. Importantly, the nonlead-exposed and female-specific subgroup analyses revealed consistency between datasets incorporating and excluding Yun et al.‘s35 results. The data from this study were also retained and utilized.

In this study, although the analysis results of the fixed-effects model showed statistically significant differences, considering the significant heterogeneity that could not be excluded from the study, the analysis results of the random-effects model were more reasonable.

Although independent of lead exposure status, BLLs were significantly higher in pediatric ALAD2 allele carriers than in ALAD1 homozygotes (p = 0.05). Only one study investigated the relationship between ALAD1/2 polymorphisms and BLLs in lead-exposed children and demonstrated that ALAD2 carriers presented higher BLLs than ALAD1 homozygotes under lead exposure conditions13. After exclusion of this single lead-exposed pediatric study, all remaining studies focused on nonlead-exposed children, and meta-analysis revealed no statistically significant associations between ALAD1/2 polymorphisms and blood lead concentrations (Table 3).

Discussion

After approximately ten thousand individual data points were included in this meta-analysis, no correlation between rs1800435 status and BLLs was found in the lead-exposed group, non-lead-exposed group, or entire investigated population. In 2007, two articles independently summarized previous data and published meta-analyses, and the conclusions were similar11,12. These results indicate that ALAD2 allele carriers had significantly greater BLLs than ALAD1 homozygous carriers did, especially among people with higher BLLs. The estimated results for low- or nonlead-exposed adults in the two meta-analyses were all negative. These findings suggest that the correlation between ALAD genotype status and BLLs may occur only in the highly lead-exposed population or in people with high blood lead concentrations. The included studies published after 2007 doubled the amount of data included in the present analysis. Those data were obtained from people in different regions of the world, including occupational lead-exposed workers, pregnant women, and children, and provide new insights for this research area.

BLLs and dietary calcium intake can mutually influence each other43,44. Vitamin D serves as the primary regulator of calcium homeostasis, with endogenous synthesis of vitamin D being dependent on the duration of sunlight exposure. A study conducted among Chinese university students revealed that the overall prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency increases with increasing latitude45. Research on nutritional supplementation during pregnancy indicates that vitamin D recommendations (typically 10 µg/day in high-latitude regions) are more frequently emphasized in high-latitude, high-income countries46. A study focusing on children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) demonstrated that vitamin D insufficiency rates in children from high-latitude regions exceed those in low-latitude areas, with significant proportions remaining insufficient even by late summer. This phenomenon becomes more pronounced during winter and in regions north of 37°N latitude47. These findings indirectly suggest that latitudinal factors may influence lead metabolism through their effects on calcium regulation. Latitude has not been systematically included as a study variable in previously published meta-analyses. We found that in some of the studies included in this analysis, the latitudinal ranges of the locations where the target populations were located were relatively fixed. Different studies have also been conducted at different geographical latitudes. These factors make the latitude factor a relatively reliable calculation index. Subgroup and regression analyses identified latitude as a source of heterogeneity and a potential moderating variable. The prevention of lead toxicity represents a critical public health priority, and incorporating latitudinal considerations could inform region-specific prevention strategies and policy formulations. Consequently, in the present study, we incorporated geographical latitude as a subgroup analysis parameter.

This research reveals novel findings and has important implications. In the lead-exposed group, for people living at non-low-latitudes (non-low latitude subgroup), ALAD2 allele carriers had higher BLLs. For people living in low-latitude areas (low-latitude subgroup), there were no statistically significant associations. In the nonlead-exposed group, latitude (low or non-low) did not significantly influence the relationship between BLLs and ALAD gene polymorphism status. However, for nonlead-exposed respondents, the BLLs of male ALAD2 allele carriers were marginally significantly lower than those of male ALAD1 homozygotes (p = 0.061).

These findings partially support previous hypotheses regarding the dose-dependent effect of ALAD2 on BLLs—specifically, that ALAD2 carriers exhibit higher blood lead concentrations than ALAD1 carriers under high lead exposure conditions11,12. In a study48 of Slovenian adult males with low lead exposure, the results revealed marginally significantly lower BLLs in ALAD2 carriers than in ALAD1 carriers at relatively low exposure levels (however, this study did not meet the inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis, and relevant data were excluded). This finding is similar to the results of this meta-analysis. The proposed hypothesis explaining this phenomenon is that δ-ALAD is highly expressed not only in erythrocytes but also in hepatic, endocrine, renal, proximal gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and GI epithelial cells9. A portion of ingested lead may be sequestered by ALAD in these tissue compartments before entering systemic circulation. At low exposure levels, ALAD2 may facilitate increased lead accumulation in cells, e.g., GI epithelial cells and hepatocytes, resulting in relatively lower BLLs than those in ALAD1 carriers. This differential effect may diminish at higher exposure levels, as substantial lead influx overwhelms tissue sequestration capacity, leading to comparable blood lead accumulation in both genotypes48.

Findings regarding the impact of ALAD2 on blood lead concentrations in females under low exposure remain highly inconsistent. A Romanian study of nonpregnant women revealed no ALAD2-mediated effect on BLLs49 (although this study did not meet inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis, relevant data were excluded). An Italian study of pregnant women demonstrated a mild reduction in maternal peripheral blood lead concentrations in ALAD2 carriers, with no observable effect on umbilical cord BLLs. In this study, the peripheral blood sampling times were as follows: 78% were collected during the second trimester (75% between 20 and 21 weeks gestation, 1% at 18–19 weeks, 2% at 22–26 weeks), and 22% during the third trimester (19% between 31 and 32 weeks, 20% at 27–30 weeks, and 1% at 33–36 weeks gestation)5. Conversely, a study of pregnant Han Chinese women suggested that ALAD2 significantly increases peripheral blood lead concentrations, with all samples collected at term delivery35. Hormonal fluctuations across pregnancy stages differentially influence the absorption, transport, and distribution of metal ions such as calcium. Research indicates that lead’s lifetime accumulation in the skeletal system may undergo mobilization during pregnancy (particularly in later stages), entering the bloodstream and transplacental transfer, potentially contributing to cumulative prenatal lead exposure5,50. Current evidence remains limited regarding female-specific lead exposure studies, particularly those investigating ALAD2 or other genetic polymorphisms under low-exposure conditions. The paucity of research and inconsistent findings preclude definitive conclusions at this time.

The paradoxical lack of association in nonexposed populations despite plausible biological mechanisms (e.g., ALAD2’s higher lead-binding affinity) may reflect gene‒environment interactions. Occupational exposure to high lead levels might amplify ALAD2-higher BLLs, whereas in general populations with lower exposure, the BLLS could be attenuated by confounding factors.

The analysis of BLLs is economical and convenient and is a clinically useful therapeutic and risk assessment biomarker for assessing the risk of lead toxicity. Zinc and erythrocyte protoporphyrin may be altered because of lead exposure, but their sensitivity and specificity are not sufficient as primary indicators. Many factors are known to affect BLLs, including gene polymorphisms, dietary calcium ion intake, nutritional status, vitamin D status, smoking, and alcohol consumption. The effects of rs1800435 on BLLs may be enhanced or weakened by other factors. Herbal supplement use helps to increase the levels of essential metals, vitamins, and dietary phytochemicals in humans, and can also have a beneficial influence by reducing lead levels. Animal studies have demonstrated that Etlingera elatior extract51zingerone52and aqueous leaf extracts of Corchorus olitorius53 exhibit protective effects against lead toxicity through their antioxidant activity and/or inhibition of lead deposition in tissues. Qader54 et al. summarized edible plants and phytochemicals that can either reduce lead levels or reverse lead toxicity, and it may be beneficial to recommend these plants and other isolated dietary phytochemicals as major dietary supplements to mitigate or prevent heavy metal poisoning.

Lead can inhibit ALAD, coproporphyrinogen oxidase, and ferrochelatase activity55,56. According to the current research, the ALAD2 allele carrier rate depends on the particular population and geographical area. The highest percentage of this allele was found in Caucasian populations. The proportion of ALAD2 gene carriers in Asian populations is relatively low5,9,35,57.

An increase in lead bound to ALAD2 results in decreased lead availability to inhibit ferrochelatase, which catalyzes heme and hemoglobin formation in the presence of Fe2+. In contrast, the weaker binding of lead to ALAD1 results in increased bioavailability of lead, which is then free to inhibit ferrochelatase. This increases the formation of zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP) and decreases the production of heme and hemoglobin. Studies have revealed that workers with the ALAD1 homozygote genotype have worse kidney function and hematological profiles than those with the ALAD2 genotype34,38. Notably, some studies have also reported different results; workers carrying the ALAD2 allele exhibited greater susceptibility to lead-induced renal impairment, particularly at elevated exposure concentrations57.

ALAD is an octameric Zn-containing enzyme that catalyzes the condensation of two ALA molecules into one porphobilinogen molecule55. Lead competes with Zn ions and displaces them from the binding site, which inhibits enzyme activity. The inhibition of ALAD results in high levels of ALA, which is structurally similar to γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) and can bind GABA receptors in the central nervous system. One study revealed that the mean urinary ALA (U-ALA) content was lower in male ALAD2 carriers than in ALAD1 males. In female children, U-ALA levels did not differ significantly. These findings indicate that ALAD2 may have a protective effect6. Other studies have also shown that ALAD2 is neuroprotective; as the BLL increases, ALAD2 is associated with increased visual attention and working memory36. Maternal BLL during delivery can affect infants, and the neonatal neurobehavioral development score (NANB) score in the high-blood lead neonatal group was obviously lower than that in the low blood lead group; however, on the basis of data in the literature, ALAD gene polymorphisms were not significantly correlated with neonatal NANB scores35.

Limitations

This study also had the following limitations: (1) the heterogeneity of the included studies was high, and the source of heterogeneity could not be fully identified by subgroup and regression analyses. (2) the included studies were from multiple countries with different latitudes, sunlight exposure times, lifestyle habits, and dietary nutrient compositions. Confounders other than latitude are difficult to assess accurately and quantitatively. Factory workers in the same region are likely to have similar dietary and lifestyle habits, which may explain why some single-center studies have positive results. (3) Our research is currently limited to rs1800435. Research has shown that many genes, including the ALAD gene, can affect the dynamic characteristics of lead metabolism. Among them, many studies have investigated rs1800435, and many studies have also demonstrated the importance of rs1800435 in lead metabolism. However, rs1800435 is not the only SNP of ALAD that can affect lead metabolism. A recent study revealed that specific combinations of ALAD SNPs can explain greater variations in lead metabolism5,48. Conducting in-depth and extensive research is highly important. (4) Unfortunately, many papers did not meet the inclusion criteria and were not included in this meta-analysis. This reduced the number of included samples and coverage areas. On the premise of protecting privacy, encouraging authors to provide detailed standardized raw data in the appendix of the main text would be more conducive to conducting such research and would also increase the influence of the original article. (5) There was publication bias in the overall group and non-lead-exposed group. These findings suggest the selective underreporting of studies with null or inverse associations. This bias likely inflated the apparent protective effect of ALAD2 in small-sample studies, whereas larger studies predominantly reported near-null effects. This implies that smaller studies disproportionately reported exaggerated protective effects of ALAD2, possibly owing to preferential publication of ‘positive’ findings in underpowered cohorts. Conversely, larger, methodologically rigorous studies (e.g., population-based cohorts with standardized lead assays) predominantly yielded null associations. The homogeneous and borderline significant results in male populations warrant further sex-specific investigations to clarify potential biological mechanisms. Future investigations should prioritize prospective designs with preregistered analysis protocols to mitigate publication bias and use individual participant data meta-analysis to disentangle gene, age, exposure, geographical latitude, etc., interactions.

Conclusions

When combining the existing work, it appears that the relationship between ALAD and BLLs could be influenced by multiple factors. The latitude of the residential area may also be a significant influencing factor because, in lead-exposed populations, ALAD2 carriers living in non-low-latitude areas had higher BLLs than ALAD1 carriers did. Sex, pregnancy status, and different stages of pregnancy may be influencing factors, and further research is needed for clarification. The role of gene–gene and gene–environment (such as dietary composition and light duration) interactions in lead poisoning needs to be further studied.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusion of this article is included in the article.

References

Vasconcellos, A. P., Colello, S., Kyle, M. E. & Shin, J. J. Societal-level risk factors associated with pediatric hearing loss: A systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 151, 29–41 (2014).

Lanphear, B. P. et al. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: An international pooled analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 894–899 (2005).

Betts, K. CDC updates guidelines for children’s lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, a268 (2012).

Bah, H. A. F. et al. Delta-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, low blood lead levels, social factors, and intellectual function in an Afro-Brazilian children community. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200, 447–457 (2022).

Palir, N. et al. ALAD and APOE polymorphisms are associated with lead and mercury levels in Italian pregnant women and their newborns with adequate nutritional status of zinc and selenium. Environ. Res. 220, 115226 (2023).

Tasmin, S., Furusawa, H., Ahmad, S. A., Faruquee, M. H. & Watanabe, C. Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism in lead exposed Bangladeshi children and its effect on urinary aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Environ. Res. 136, 318–323 (2015).

Wetmur, J. G., Kaya, A. H., Plewinska, M. & Desnick, R. J. Molecular characterization of the human delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase 2 (ALAD2) allele: Implications for molecular screening of individuals for genetic susceptibility to lead poisoning. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 49, 757–763 (1991).

Battistuzzi, G., Petrucci, R., Silvagni, L., Urbani, F. R. & Caiola, S. delta-Aminolevulinate dehydrase: A new genetic polymorphism in man. Ann. Hum. Genet. 45, 223–229 (1981).

Kelada, S. N., Shelton, E., Kaufmann, R. B. & Khoury, M. J. Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype and lead toxicity: A huge review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154, 1–13 (2001).

Süzen, H. S., Duydu, Y., Aydin, A., Işimer, A. & Vural, N. Influence of the delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism on biomarkers of lead exposure in Turkish storage battery manufacturing workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 43, 165–171 (2003).

Zhao, Y. et al. Association between delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism and blood lead levels: A meta-regression analysis. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 70, 1986–1994 (2007).

Scinicariello, F. et al. Lead and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase polymorphism: where does it lead? A meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 35–41 (2007).

Wetmur, J. G., Lehnert, G. & Desnick, R. J. The delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase polymorphism: higher blood lead levels in lead workers and environmentally exposed children with the 1–2 and 2–2 isozymes. Environ. Res. 56, 109–119 (1991).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Smith, C. M., Wang, X., Hu, H. & Kelsey, K. T. A polymorphism in the delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase gene May modify the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of lead. Environ. Health Perspect. 103, 248–253 (1995).

Alexander, B. H. et al. Interaction of blood lead and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype on markers of Heme synthesis and sperm production in lead smelter workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 106, 213–216 (1998).

Fleming, D. E. et al. Effect of the delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase polymorphism on the accumulation of lead in bone and blood in lead smelter workers. Environ. Res. 77, 49–61 (1998).

Sakai, T., Morita, Y., Araki, T., Kano, M. & Yoshida, T. Relationship between delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotypes and Heme precursors in lead workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 38, 355–360 (2000).

Schwartz, B. S. et al. Associations of blood lead, dimercaptosuccinic acid-chelatable lead, and tibia lead with polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor and [delta]-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genes. Environ. Health Perspect. 108, 949–954 (2000).

Hsieh, L. L. et al. Association between aminolevulinate dehydrogenase genotype and blood lead levels in Taiwan. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 42, 151–155 (2000).

Shen, X. M. et al. Delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase polymorphism and blood lead levels in Chinese children. Environ. Res. 85, 185–190 (2001).

Duydu, Y. & Süzen, H. S. Influence of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism on the frequency of sister chromatid exchange (SCE) and the number of high-frequency cells (HFCs) in lymphocytes from lead-exposed workers. Mutat. Res. 540, 79–88 (2003).

Kamel, F. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, lead, and genetic susceptibility: Polymorphisms in the delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and vitamin D receptor genes. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 1335–1339 (2003).

Kim, H. S. et al. The protective effect of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase 1–2 and 2–2 isozymes against blood lead with higher hematologic parameters. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 538–541 (2004).

Pérez-Bravo, F. et al. Association between aminolevulinate dehydrase genotypes and blood lead levels in children from a lead-contaminated area in antofagasta, Chile. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 47, 276–280 (2004).

Wu, F. Y., Chang, P. W., Wu, C. C., Lai, J. S. & Kuo, H. W. Lack of association of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype with cytogenetic damage in lead workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 77, 395–400 (2004).

Montenegro, M. F., Barbosa, F. Jr., Sandrim, V. C., Gerlach, R. F. & Tanus-Santos J. E. A polymorphism in the delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase gene modifies plasma/whole blood lead ratio. Arch. Toxicol. 80, 394–398 (2006).

Wananukul, W., Sura, T. & Salaitanawatwong, P. Polymorphism of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and its effect on blood lead levels in Thai workers. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health. 61, 67–72 (2006).

Weuve, J. et al. Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase polymorphism and the relation between low level lead exposure and the Mini-Mental status examination in older men: the normative aging study. Occup. Environ. Med. 63, 746–753 (2006).

Chen, Y. et al. Lack of association of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype with blood lead levels in environmentally exposed children of Uygur and Han populations. Acta Paediatr. 97, 1717–1720 (2008).

Miyaki, K. et al. Association between a polymorphism of aminolevulinate dehydrogenase (ALAD) gene and blood lead levels in Japanese subjects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 6, 999–1009 (2009).

Scinicariello, F., Yesupriya, A., Chang, M. H. & Fowler, B. A. Modification by ALAD of the association between blood lead and blood pressure in the U.S. Population: Results from the third National health and nutrition examination survey. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 259–264 (2010).

Fang, F. et al. Association between blood lead and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 171, 1126–1133 (2010).

Wan, H., Wu, J., Sun, P. & Yang, Y. Investigation of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase polymorphism affecting hematopoietic, hepatic and renal toxicity from lead in Han subjects of Southwestern China. Acta Physiol. Hung. 101, 59–66 (2014).

Yun, L., Zhang, W. & Qin, K. Relationship among maternal blood lead, ALAD gene polymorphism and neonatal neurobehavioral development. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8, 7277–7281 (2015).

Sobin, C., Flores-Montoya, M. G., Gutierrez, M., Parisi, N. & Schaub, T. δ-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase single nucleotide polymorphism 2 (ALAD2) and peptide transporter 2*2 haplotype (hPEPT2*2) differently influence neurobehavior in low-level lead exposed children. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 47, 137–145 (2015).

Mani, M. S. et al. Modifying effects of δ-Aminolevulinate dehydratase polymorphism on blood lead levels and ALAD activity. Toxicol. Lett. 295, 351–356 (2018).

Siha, M. S., Shaker, D. A., Teleb, H. S. & Rashed, L. A. Effects of delta-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase gene polymorphism on hematological parameters and kidney function of Lead-exposed workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 10, 89–93 (2019).

Alvarez-Ortega, N., Caballero-Gallardo, K. & Olivero-Verbel, J. Toxicological effects in children exposed to lead: A cross-sectional study at the Colombian Caribbean Coast. Environ. Int. 130, 104809 (2019).

Schwartz, B. S. et al. Associations of delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype with plant, exposure duration, and blood lead and zinc protoporphyrin levels in Korean lead workers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 142, 738–745 (1995).

Hu, H. et al. The delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism and bone and blood lead levels in community-exposed men: the normative aging study. Environ. Health Perspect. 109, 827–832 (2001).

Wu, M. T. et al. A delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) polymorphism May modify the relationship of low-level lead exposure to uricemia and renal function: the normative aging study. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 335–341 (2003).

Mahaffey, K. R., Gartside, P. S. & Glueck, C. J. Blood lead levels and dietary calcium intake in 1- to 11-year-old children: The second National health and nutrition examination survey, 1976 to 1980. Pediatrics 78, 257–262 (1986).

Han, S. et al. Effects of lead exposure before pregnancy and dietary calcium during pregnancy on fetal development and lead accumulation. Environ. Health Perspect. 108, 527–531 (2000).

Luo, Y. et al. Geographic location and ethnicity comprehensively influenced vitamin D status in college students: A cross-section study from China. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 42, 145 (2023).

Saros, L. et al. Micronutrient supplement recommendations in pregnancy vary across a geographically diverse range of countries: A narrative review. Nutr. Res. 123, 18–37 (2024).

Miller, M. C. et al. Vitamin D levels in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Association with seasonal and geographical variation, supplementation, inattention severity, and theta:beta ratio. Biol. Psychol. 162, 108099 (2021).

Stajnko, A. et al. Genetic susceptibility to low-level lead exposure in men: Insights from ALAD polymorphisms. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 256, 114315 (2024).

Rabstein, S. et al. Lack of association of delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase polymorphisms with blood lead levels and hemoglobin in Romanian women from a lead-contaminated region. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 71, 716–724 (2008).

Skerfving, S. & Bergdahl, I. Lead. In: (eds Nordberg, G. F., Fowler, G. F. & Nordberg, M. Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, fourth ed. Elsevier, Academic Press, New York, 911–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2011-0-07884-5. (2015).

Haleagrahara, N., Jackie, T., Chakravarthi, S., Rao, M. & Pasupathi, T. Protective effects of Etlingera elatior extract on lead acetate-induced changes in oxidative biomarkers in bone marrow of rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48, 2688–2694 (2010).

Amin, I. et al. Zingerone prevents lead-induced toxicity in liver and kidney tissues by regulating the oxidative damage in Wistar rats. J. Food Biochem. 45, e13241 (2021).

Dewanjee, S., Sahu, R., Karmakar, S. & Gangopadhyay, M. Toxic effects of lead exposure in Wistar rats: Involvement of oxidative stress and the beneficial role of edible jute (Corchorus olitorius) leaves. Food Chem. Toxicol. 55, 78–91 (2013).

Qader, A., Rehman, K. & Akash, M. S. H. Genetic susceptibility of δ-ALAD associated with lead (Pb) intoxication: Sources of exposure, preventive measures, and treatment interventions. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 28, 44818–44832 (2021).

Warren, M. J., Cooper, J. B., Wood, S. P. & Shoolingin-Jordan, P. M. Lead poisoning, haem synthesis and 5-aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 217–221 (1998).

Onalaja, A. O. & Claudio, L. Genetic susceptibility to lead poisoning. Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (Suppl 1), 23–28 (2000).

Chia, S. E. et al. Association of renal function and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase polymorphism among Vietnamese and Singapore workers exposed to inorganic lead. Occup. Environ. Med. 63, 180–186 (2006).

Wetmur, J. G. Influence of the common human delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase polymorphism on lead body burden. Environ. Health Perspect. 102 (Suppl 3), 215–219 (1994).

Schwartz, B. S. et al. Associations of subtypes of hemoglobin with delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype and dimercaptosuccinic acid-chelatable lead levels. Arch. Environ. Health. 52, 97–103 (1997).

Schwartz, B. S. et al. delta-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype modifies four hour urinary lead excretion after oral administration of dimercaptosuccinic acid. Occup. Environ. Med. 54, 241–246 (1997).

Sithisarankul, P., Schwartz, B. S., Lee, B. K., Kelsey, K. T. & Strickland, P. T. Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genotype mediates plasma levels of the neurotoxin, 5-aminolevulinic acid, in lead-exposed workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 32, 15–20 (1997).

Lee, B. K. et al. Associations of blood pressure and hypertension with lead dose measures and polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase genes. Environ. Health Perspect. 109, 383–389 (2001).

Lee, S. S. et al. Associations of lead biomarkers and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and vitamin D receptor genotypes with hematopoietic outcomes in Korean lead workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 27, 402–411 (2001).

Weaver, V. M. et al. Associations of renal function with polymorphisms in the delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, vitamin D receptor, and nitric oxide synthase genes in Korean lead workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 1613–1619 (2003).

Weaver, V. M. et al. Associations of uric acid with polymorphisms in the delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, vitamin D receptor, and nitric oxide synthase genes in Korean lead workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 1509–1515 (2005).

Weaver, V. M. et al. Effect modification by delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, vitamin D receptor, and nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms on associations between patella lead and renal function in lead workers. Environ. Res. 102, 61–69 (2006).

Acknowledgements

JK, J and XJ, X designed the study, writing plans and literature search strategies. XJ, X and JK, J separately conducted the literature search, data evaluation, and input, and the as well as statistical and meta-analyses separately. JK, J wrote the draft of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. This study was conducted without funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing published literature. As such, it did not involve direct collection of new human/animal data or human tissue samples. Ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board or ethics committee and informed consent were therefore not required for this work. All methods were performed in strict accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. The ethical compliance of each primary study included in this analysis remains the sole responsibility of its original investigators, as stated in their respective publications.

Data availbility

The dataset supporting the conclusion of this article is included in the article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, J., Xie, X. Effects of the δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase polymorphism rs1800435 on blood lead levels: a new systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 30123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14850-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14850-y