Abstract

The aim was to study the consequences of ignoring dominance effects from the genomic evaluation model on the accuracy, mean square error, bias, and dispersion of genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for a discrete threshold trait. Also, the predictive performance of the parametric and non-parametric genomic selection models was compared. A genome consisting of 10 chromosomes, on which 10,000 bi-allelic single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) were distributed was simulated. In different scenarios, 100, 500, and 1000 SNPs were assigned to quantitative trait loci (QTL). For QTL effects, different distributions (normal, uniform, and gamma) were considered. While all QTLs were assigned additive genetic effects, in different scenarios, dominance effects were given to 0.00, 10, 25, 50, and 100% of QTLs. The GEBVs were estimated using the GBLUP, Bayesian methods, ridge regression variants, and machine learning methods. The criteria of the LR method such as prediction accuracy, mean square error, bias, and dispersion were used to analyze GEBVs. The results showed that if dominance effects were present, but not included in the model, caused to 14 to 31% decrease in the accuracy of the GEBVs. Also, the mean square error of GEBVs increased between 19 and 47%, following an increase in the percentage of QTLs with a dominance effect from 0.00 to 100%. In addition, the bias of GEBVs increased between 20 and 42%, and a 50% increase was observed in the dispersion of GEBVs by ignoring dominance effects. Results showed that when the genetic architecture of the traits is purely additive, or when dominance effects are present but ignored from the genomic evaluation process, GBLUP, BayesB, and ridge regression BLUP-method 6 (rrBLUPm6) had better predictive performance, and therefore recommended for genomic evaluation of discrete threshold traits. Machine learning methods, in particular regression tree, had poor predictive performance and were not recommended for genomic selection. In general, the results showed that not accounting for dominance effects when they are really present, leads to inaccurate, biased, and dispersed estimates of GEBVs, which will ultimately reduce the efficiency of genomic selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For many years, before discovering Gregor Mendel’s principles of inheritance, which form the cornerstone of modern genetics, animal breeding was not complicated and the phenotypic records were the basis for selection. In most cases, because of environmental noises, phenotypic selection did not guarantee the selection of superior animals and, therefore, was not an effective selection strategy. From the middle of the 20th century, combining phenotypic records and genealogical information in the framework of an ‘animal model” became the standard approach to estimate so-called “breeding values” of animals by which superior animals were selected to make genetic improvements in the traits of interest1. While the animal model had a successful application in animal breeding, the accuracy of the breeding values obtained by this method was affected by several factors, including the number of phenotypic records, the depth and quality of the pedigree and the model used. In addition, there was limitation for using this method for traits that could not be measured in live animals such as carcass traits, and sex-limited traits such as milk production in dairy cows and egg production in poultry2. Inventing marker-assisted selection (MAS), claiming the increase in genetic improvement compared to the conventional BLUP method was a turning point in the world of animal breeding. However, in practice, MAS was not effective because the additional improvement it could provide was not more than 2.5%3, and for this reason, it was not widely used. During the last two decades, with the invention of new DNA technologies, it became possible to sequence the genome of domestic animals on a large scale. Genome-level studies showed that there were a large number of DNA markers in the form of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at the genome level, which created a very high diversity in livestock populations. This diversity was a prerequisite for genomic selection. Meuwissen et al.4 founded the principles of genomic selection and, for the first time, by using computer simulation and combining it with Bayesian methods, estimated the GEBVs of selection candidates using genotypic information of about 50,000 SNPs. A better estimation of the Mendelian sampling component, an increase in accuracy, and a reduction in the generation interval can be mentioned among the main advantages of the use of genomic data for breeding value estimation5. The last decade has witnessed a rapid increase in activity in this area. High-density SNP chips such as BovineHD including 777,962 SNPs have been developed, strategies to decrease the cost of genomic selection such as genotype imputation have been suggested6 and many efficient statistical methods to estimate SNP effects have been developed7. Doublet et al.8 studied the effect of genomic selection on the genetic improvement of three breeds of dairy cows in France: Montbéliard, Normandy, and Holstein, and reported that compared to conventional selection strategies, genomic selection increased the average annual genetic gain between 33% (Holstein) to 71% (Normandy).

The review of published articles in the field of genomic selection shows that in most of the studies in animal and crop species, prediction of genomic breeding values has been done without considering dominance effects9,10,11,12. It was because of (1) the lack of an informative pedigree that contains a high percentage of full-sib families, (2) an increase in the computational complexity in case of introducing non-additive effects into the model, (3) the fact that additive genetic effects capture, to some extent, dominance genetic effects, (4) the difficulty in using non-additive genetic information in breeding plans13 and (5) larger training datasets are required for the modeling of non-additive effects than datasets required for the modeling of additive effects14. This is why little efforts have been made to quantify the extent to which dominance effects contributed to the phenotypic variation of performance traits of domestic animals. However, the results of recently published articles show that dominance effects significantly contribute to the phenotypic variation of production and reproduction traits of domestic animals15,16,17,18. For example, Jasouri et al.15 investigated the contribution of dominance effects to the phenotypic variation of body weight traits and egg production traits of native fowl and reported that the contribution of dominance effects to the phenotypic variation of body weight at birth, eight weeks, and twelve weeks were 0.06, 0.08, and 0.01, respectively. In addition, for the age at sexual maturity, average egg weight and number of eggs, the ratio of dominance variance to phenotypic variance (dominance heritability) was 0.06, 0.06 and 0.08, respectively. In Adani goats, Sadeghi et al.18 estimated dominance heritability for body weight at birth, weaning, six months, nine months, and twelve months as 0.15, 0.17, 0.11, 0.19, and 0.25, respectively. For these traits, the additive heritability was in the range between 0.17 (weaning weight) and 0.38 (birth weight). The role of dominance in the Holstein and Jersey breeds was investigated for eight traits: milk, fat, and protein yields, productive life, daughter pregnancy rate, somatic cell score, fat percent, and protein percent. While for non-yield traits, dominance variances were very small for both breeds, for yield traits, dominance variance accounted for 5 and 7% of total variance for Holsteins and Jerseys, respectively19. Li et al.20 reported that dominance variance of broiler feed-related traits accounted for 29.5–58.4% of the genetic variance. In addition, the universal phenomenon of heterosis in animals and plants also indicates that dominance effects are substantial21. Therefore, according to these reports, it seems that including dominance effects in the genomic evaluation model can (1) lead to a better understanding of the genetic architecture of traits, (2) increase the accuracy of genomic evaluation, and (3) improve the efficiency of breeding programs via determining the relative importance of dominance effects13.

Many traits are phenotypically discrete but polygenically determined. These traits, which do not follow Mendel’s Law of Dominance, are termed ‘threshold’ or ‘quasicontinuous22. They are complex traits because multiple genetic and environmental factors impact the phenotype23. Liability to disease, conformation, and type scores, survival or death, degree of dystocia, and litter size are good examples of threshold traits22. In dealing with threshold traits we have two variables, the one that is observed (phenotype) and the one that is latent (latent variable or liability) (Fig. 124). As long as the latent variable (such as the level of a hormone in the blood which continuously changes in the population) is below the threshold, we observe the first phenotype, and when the latent variable crosses the threshold, the second phenotype emerges. In other words, individuals above the threshold display one phenotype, and individuals below the threshold display the alternate phenotype23,25. Phenotypic classes are determined by the number of thresholds as number of thresholds + 1. The heritability of threshold traits is typically large enough (> 0.30) to respond to modest selection intensity26. Therefore, a moderate response to selection is expected in these traits through selection. González-Recio and Forni27 performed a genomic evaluation for scrotal hernia in pigs with one threshold and reported that the accuracy of genomic evaluation was relatively low. Ghasemi et al.28 studied the effect of numbers of thresholds on the accuracy of genomic evaluation and reported that by increasing the number of thresholds, the accuracy of genomic evaluation increased. Despite these efforts, the effect of ignoring dominance effects on the accuracy of genomic evaluation of discrete threshold traits has not been studied so far. Therefore, this study was conducted in order to investigate the consequences of ignoring dominance effects from the genomic evaluation model on the accuracy, mean square error, bias, and dispersion of GEBVs. The predictive performance of different genomic selection methods was also compared.

Materials and methods

Population and genome simulation

Genome and population were simulated with package hyperd version 0.429 in R software30. Parameters used for the simulation of the genome and population are listed in Table 1. 10 chromosomes formed the genome, on which 10,000 SNPs were uniformly distributed. Coding for each genotype with alleles A1 and A2 were, respectively, 2 for A1A1, 0 for A2A2, and 1 for A1A2 or A2A1. In different scenarios, 100, 500, and 1000 SNPs were assigned to quantitative trait loci (QTL). The mutation rate at the marker loci was 2.5 × 10− 3 to provide a high probability of polymorphic marker loci. This was 2.5 × 10− 5 per locus per generation for each QTL4. The additive heritability was set to be 0.5. To simulate the population, first, a base population including 50 males and 50 females was simulated, and random mating was performed for 50 generations. Two progenies were born from each mating. Therefore, during 50 generations, the population size remained constant at 100 individuals (Ne=100). At the end of 50 generations, the linkage disequilibrium (LD) measured by r2 reached 0.23, which was in the range of 0.13–0.51 reported for different breeds of dairy cows genotyped with high-density SNP platforms31. The size of the population in the 51st generation was increased to 1000 individuals. These animals had both genotypic and phenotypic information and formed the reference (train) population. The phenotype of the animals was obtained through the sum of the genetic value of QTLs and an environmental component obtained from a normal distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation equal to the square root of the environmental variance. In order to convert the normal phenotype into a threshold phenotype, the Probit function22 was used. Using the Probit function, the phenotypic category of each individual is determined according to the individual’s phenotypic value and the threshold points. At its foundation, Probit regression assumes that there exists an unobserved (latent) continuous variable that dictates the observed binary outcome. Formally, if we denote this latent variable by \(\:\lambda\:\), the model is represented as:

where B1, B2, and Bk are regression coefficients and x1, x2, and xk are independent variables. The observed binary outcome is obtained by applying a threshold to the latent variable:

Following tradition, we fixed the threshold to be 0.

Then generation 52 was generated from individuals of the reference population. Individuals in generation 52 only had genotypic information but no phenotypic information and were labeled as validation population (selection candidates) for which GEBVs had to be predicted.

Scenarios examined

-

(1)

Number of QTL: The number of QTL was considered as a percentage of the number of SNPs (1, 5 and 10%, namely 100, 500 and 1000 QTLs).

-

(2)

Distribution of QTL effects: The distribution of QTL effects was modeled by gamma, uniform, and normal distributions. In gamma distribution, the shape (β) and scale parameters were set to 0.4 and 1.66, respectively4. In uniform distribution, the QTL effects ranged between 0 and 1 with the same probability, and in normal distribution, the QTL effects were sampled from a standard normal distribution, \(\:{g}_{\varvec{i}}\sim N\left(0,1\right)\), where \(\:g\) is the QTL effect.

-

(3)

Dominance effects: To assign dominance effects to QTLs, different scenarios were considered: in the first scenario, all QTLs were given only an additive effect (scenario A). In the second scenario, all QTLs were given an additive effect, and 10% of them were given a dominance effect (scenario A + 10%D). In the third scenario, all QTLs were given an additive effect, and 25% of them were given a dominance effect (scenario A + 25% D). In the fourth scenario, an additive effect was given to all QTLs, and a dominance effect was considered for 50% of them (scenario A + 50% D). In the fifth scenario, all QTLs were given both additive, and dominance effects (scenario A + 100%D).

Genomic evaluation methods

Genomic best linear unbiased prediction (GBLUP)

The statistical model was as follows32:

where y is the vector of phenotypic observations and µ is the overall mean. X matrix elements include codes 0, 1, and 2, which indicate the number of alleles related to each of the SNPs for each individual. b is the vector of genomic breeding values and e is the vector of residual effects. BGLR package version 1.0333 was used for GBLUP analyses in R software30.

Bayesian methods (BayesA, BayesB, BayesC)

The main assumption of BayesA is that of the total number of loci underlying a quantitative trait, only a small number have large effects, and remained others have small effects. BayesA was fitted using the following model:

where y is the vector of phenotypic observations, X is an incidence matrix associating observations to fixed effects in β, k denotes the number of SNPs, \(\:{\varvec{z}}_{k}\) is an N × 1 vector of genotypes at SNP k,\(\:{\:a}_{k}\) is the additive effect of that SNP, and e is a vector of residual effects. The BayesA uses the Student’s t-distribution as a prior of the SNPs effects, which is implemented as a mixture of normal distribution, that is, z ∼ N(0, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{z}^{2})\). In BayesB, it is assumed that only parts of the loci explain the entire genetic variance, and many loci do not contribute to genetic variance. BayesB can be written as follows:

where y is the phenotype of the animal i, µ is the mean, k is the number of marker loci, and x is the genotype of the marker at the locus j (ith allele) which is encoded as 0, 1, and 2 (number of copies of the SNP allele carried by the ith animal). βj is the effect of allelic substitution at position j and δj which is coded as 0 and 1 indicates the absence (with probability π) or the presence (with probability 1- π) of the locus j in the model4. BayesC is a special type of BayesB, and in some articles, it is also referred to as BayesCπ. In BayesC, the normal distribution is used instead of the t-distribution to model the marker effects, and as a result, the posterior distribution will also be normalized. The Bayesian methods A, B, and C were run using package BGLR version 1.0333 in R software30.

Ridge regression BLUP (rrBLUP) and ridge regression BLUP-method 6(rrBLUPm6)

In rrBLUP, the predicted GEBVs are obtained by the summing of all the marker effects of an individual. Marker effects were estimated using the following mixed model:

where y is the vector of observed phenotypes, 1n is a column vector of n ones and µ is a common intercept, Z is the design matrix for the random marker effects, and g is the vector of random marker effects. In RR-BLUP, the residuals and marker effects follow normal distributions with constant variance, i.e., e ~ N (0, I\(\:{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}\)) and g ~ N(0, I\(\:{\sigma\:}_{g}^{2}\)), where I is an identity matrix. Under the assumed model the variance of the observed data is:

In which ZT denotes the transpose of Z and R is the residual covariance matrix and equals to \(\:{\varvec{I}}_{n}{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}\). The solution for the marker effects is given by the following equation:

where \(\:\lambda\:\) =\(\:{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}/{\sigma\:}_{g}^{2}\) is the ridge penalization parameter. The R package BGLR version 1.0333 was used to run rrBLUP.

In the rrBLUPm6, the marker effects are estimated by the following Eq. 34:

The method is restricted to the case in which R = \(\:{\varvec{I}}_{n}{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}\). In case R does not meet this assumption, a linear transformation is applied to ensure R = \(\:{\varvec{I}}_{n}{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}\). Therefore, we would replace y with LRy and Z with LRZ, in which R–1 = (LR)2 such that LR is square and symmetric. LR is easily obtained from a spectral decomposition of R-1. With these replacements, analysis can proceed assuming that R =\(\:{\varvec{I}}_{n}{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}\) with \(\:{\sigma\:}_{e}^{2}\) = 1. For more details, refer to Piepho et al.34. The R package rrBlupMethod6 version 1.0335 was used to run rrBLUPm6 in R software30.

Regression tree-based methods (Regression tree, Random Forest, Boosting)

Regression tree (RT) analysis is when the predicted outcome can be considered a real number (e.g., daily milk production). Let y (n×1) be the vector observations, and X ={xi}, where xi is a (p×1) vector representing the genotype of each animal for p SNP. The RT model can be represented as follows:

1) The RT is constructed as follows: (1) different samples from the training data set, i.e., {(x1, y1),., (xn, yn)}, are drawn with replacement, (2) a small group of SNP is randomly selected from the p SNP marker and the SNP j which minimizes the lose function is selected, (3) according to the genotype of SNP j, the node is split in two child nodes and individuals go to one of the child nodes according to the SNP alleles they carry, (4) steps 2–3 are repeated until a minimum node size is reached (usually < 5) and all the terminal nodes become maximally homogeneous. The predicted value of the genotype xi for regression problems is the average phenotype of the individuals in the node27. The package rpart version 4.1.1036 was used to run RT in R software30.

Random Forest (RF) regression uses an ensemble of regression trees, grown on bootstrap samples of observations using a random subset of predictors to define the best split at each node. The RF prediction for a new observation\(\:\:x\left({\widehat{f}}_{rf}^{B}\left(x\right)\right)\), is computed by averaging the predictions over B trees,\(\:\:\{T\left(x.{\varPsi\:}_{b}\right){\}}_{1}^{B}\), for which the given observation was not used to build the tree. Where \(\:{\varPsi\:}_{b}\) characterizes the bth RF tree in terms of split variables, cut points at each node, and terminal node values. The package randomForest version 4.6.1037 was used for the analysis of data in the framework of the following model:

RF has three important hyperparameters: the number of trees to grow (ntree), the number of SNPs randomly selected at each tree node (mtry), and the minimum size of terminal nodes of trees, below which no split is attempted (nodesize). The optimum combination of these parameters should be used while running RF. With a grid search, we test different combinations of hyperparameters to identify the set of hyperparameters that result in the best model performance. The combination which provided the highest accuracy was: ntree = 1500, mtry = 100, and nodesize = 20.

The Boosting algorithm uses a regression tree as the “base” or “weak” learner and successively feeds it a random sample of the training data. Each time the base learner produces a new weak prediction rule, and after many rounds, the boosting algorithm combines these weak rules into a single and robust prediction rule that will be much more accurate than any one of the weak rules. The following model was used to fit the Boosting algorithm:

where \(\:{\beta\:}_{m}\), m = 1, 2,…, M are the basis expansion coefficients, and b(x, \(\:\gamma\:\)) are simple functions of the multivariate argument x, with a set of parameters \(\:\gamma\:\) =(\(\:\:\gamma\:\)1,\(\:\:\gamma\:\)2,…,\(\:\:\gamma\:\)M). Prediction is accomplished by weighting the ensemble outputs of all the regression trees. Important hyperparameters of Boosting are the number of tree (ntree), tree depth or tree complexity (tc), and shrinkage rate or learning rate (lr). We specified a series of values for each hyperparameter and then a grid search was used to evaluate the performance of the model with each combination of tuning hyperparameters. The combination that provided the highest accuracy was: ntree = 1500, tc = 7 and lr = 0.01. The R package gbm version 2.2.138 was used to run Boosting.

Analysing the GEBVs

Some criteria of the Legarra and Reverter39 (LR method) were used to analyze the GEBVs. These were:

1) Prediction accuracy: This criterion was calculated as Pearson’s correlation between predicted and true (simulated) breeding values.

2) Mean Square Error of prediction (MSEp): this criterion was calculated as the square root of the difference between the true and predicted genomic breeding values.

3) Bias: this criterion was calculated as the difference between the average predicted breeding values and true breeding values.

4) Dispersion: This is the slope of the regression of true breeding values on predicted breeding values. If over- or under-dispersion does not exist, the expected value of the estimator is 1. Values of \(\:\widehat{d}\) < 1 indicate over-dispersion (inflated), whereas values of \(\:\widehat{d}\) > 1 indicate under-dispersion (deflated).

Each studied scenario was analyzed 10 times and the average of 10 replications was reported.

Results

The effect of increasing the percentage of QTLs with dominance effect on the accuracy of GEBVs in different scenarios of distribution of QTL effects and the number of QTLs is shown in Table 2. As observed, when a purely additive model was used, the accuracy of the genomic evaluation decreased with the increase in the percentage of QTLs with dominance effect. For example, in the normal distribution of QTL effects and the scenario of 1000 QTLs, by increasing the percentage of QTLs with dominance effect from zero to 100%, the accuracy of genomic evaluation decreased by 31% (P < 0.05). The noteworthy point was that with the increase in the number of QTLs with dominance effect from 0.00 to 25%, the prediction accuracy did not decrease significantly, and the major decrease was observed in the scenarios of 50% and 100% QTLs with dominance effect. In addition, the slope of the decrease in accuracy of genomic evaluation as a result of assigning dominance effect to QTLs was more significant in the case where 1000 QTLs controlled the trait, and by moving from 1000 QTLs to 100 QTLs, the rate of decrease in accuracy reduced (31% vs. 16%). In each scenario of the percentage of QTLs with dominance effect, there was a slight increase in accuracy following the reduction in the number of QTLs from 1000 to 100 QTLs.

The MSEp of GEBVs is listed in Table 3. The lowest MSEp was obtained in the case where none of the QTLs had dominance effect (scenario A) and increased significantly (P < 0.05) and maximized in the scenario A + 100%D. In each scenario of the percentage of QTLs with dominance effect, MSEp decreased dramatically as the number of QTLs decreased. For example, in the normal distribution of QTL effects, in the A + 25%D scenario, by reducing the number of QTLs from 1000 to 100 QTLs, MSEp decreased by 83%.

The bias of genomic breeding values is shown in Table 4. In all the studied scenarios, the upwards-biased GEBVs (GEBVs of selection candidates were higher than their true GEBVs) were obtained even in scenario A; however, the most biased GEBVs were obtained in scenario A + 100%D. In the normal distribution of QTL effects, by moving from scenario A to scenario A + 100%D, the bias increased significantly (P < 0.05) by 32% (1000 QTLs), 28% (500 QTLs), and 20% (100 QTLs), respectively. It was 28%, 27%, and 26% in uniform distribution and 42%, 33%, and 27% in gamma distribution for 1000, 500, and 100 QTLs scenarios, respectively. Similar to MSEp, in each scenario of the number of QTLs with dominance effect, the bias of GEBVs decreased by reducing the number of QTLs from 1000 to 100 QTLs.

Table 5 shows the dispersion of the GEBVs. In all studied scenarios, there was under-dispersion (\(\:\widehat{d}\)>1), i.e., the GEBV of the selection candidates was deflated. In all the studied scenarios of the QTL number and distribution of QTL effects, the dispersion increased significantly (P < 0.05) as the number of QTLs with dominance effects increased. The least and most deflated GEBVs were observed in scenarios A and A + 100%D, respectively.

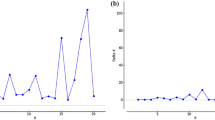

Criteria of the LR methods for genomic selection models in the scenario of 1000 QTL, Gamma distribution of QTL effects, and A + 100%D are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5 (similar results were observed in other scenarios, not shown). Among the studied models, four models had an accuracy higher than 0.7 (GBLUP, BaysA, BayesB, rrBLUPm6). RT had significantly lower accuracy than other methods and ranked last (Fig. 2). Concerning mean square error of prediction (MSEp), regression tree-based methods (RT, RF, Boosting) and rrBLUPm6 provided breeding values with the highest and least MSEp, respectively, though the difference between rrBLUPm6 with GBLUP, BaysA, BayesB, BayesC, and rrBLUP was non-significant (Fig. 3). Regarding the bias of GEBVs, here too, regression-tree based methods (RT, RF and Boosting) had significantly higher bias than other methods. BayesB and rrBLUPm6 had least bias (Fig. 4). While BayesB and rrBLUPm6 provided GEBVs with the least dispersion, the GEBVs that obtained by RT, RF, and Boosting experienced maximum dispersion (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In the current study, although dominance effects were present and contributed to the variation of the trait, a purely additive model was used to predict GEBVs to see if ignoring dominance effects from the genomic selection model negatively affected the accuracy, MSEp, bias, and dispersion of GEBVs or not. Accuracy is how close a given set of measurements (observations) are to their true value. A model whose prediction accuracy is greater and close to 1.00 is favored for genomic evaluation. Mohammadi et al.40 performed a genomic evaluation on milk yield and fat and protein content in Iranian Holstein dairy cows. Although the contribution of the dominance effects to the phenotypic variation of the mentioned traits was low (2%, 1% and, 1%, respectively), by including dominance effects in the model, the accuracy of genomic evaluation for milk yield, fat and protein content increased by 3%, 5% and 6%, respectively, compared to the model that only consider additive effects. Also, using computer simulation, Mohammadi and Sattaei Mokhtari41 showed that including dominance effects in the model increased the accuracy of genomic evaluation in a way that in the BayesA and BayesB, the accuracy of genomic evaluation increased by 9% and 3%, respectively. Nishio and Satoh42 evaluated the performance of GBLUP including dominance effect (GBLUP-D) by estimating variances and predicting genetic merits in a computer simulation and 2 actual traits in pigs. GBLUP-D yielded estimates of total genetic effects over 1.2% more accurate than those yielded by GBLUP. They concluded that, in particular, when dominance genetic variance was large, the accuracy could be substantially improved by applying GBLUP-D. For yield traits of Holsteins and Jerseys, including additive and dominance effects fit the data better than including only additive effects; average correlations between estimated genetic effects and phenotypes showed that prediction accuracy increased when both effects rather than just additive effects were included19. Nonetheless, there are reports showing no change in the accuracy by including dominance effects in the model, mainly related to crop species. For example, Morais et al.43 compared additive and additive + dominance models in the genomic evaluation of performance traits in rice and reported that presenting dominance effects to the model did not improve the prediction accuracy. Also, Yadav et al.44 evaluated the accuracy of genomic evaluation of sugarcane production traits, including cane per hectare, sugar content, and fiber content, using additive and additive + dominance models. For the cane per hectare, dominance variance accounted for nearly 70% of the total genetic variance, and the inclusion of dominance effect in the model increased the accuracy of the genomic evaluation up to 26%, but for sugar and protein content, dominance variance was negligible and had no effect on the accuracy.

The MSEp is one of the important indicators for analyzing the results of genomic evaluation. This parameter reflects simultaneously the accuracy and bias of the GEBVs and smaller and close to zero estimates of MSEp is desirable. Aliloo et al.45 investigated the effect of including dominance effects in the model for the genomic evaluation of milk yield, fat, and protein yields in Holstein and Jersey cows. The comparison of models showed that the model including both additive and dominance components led to a better data fit. The contribution of dominance effects to the phenotypic variation of investigated traits was between 3 and 4% in the Holstein breed and between 6 and 7% in the Jersey breed. For the investigated traits, in both breeds, the model that contained additive and dominance effects had lower MSEp compared to the purely additive model. By simulating a quantitative trait and considering purely additive and additive + dominance genetic architecture, Mohammadi and Sattaei Mokhtari41reported that by including dominance effects in the model , MSEp in BayesA, BayesB, and BayesL, decreased by 5%, 5%, and 4%, respectively, which is in agreement with current results.

From a breeding point of view, unbiased estimates of breeding values are needed to correctly predict response to selection. The biased estimates of GEBVs could lead to over-or under-estimation of genetic trends and to poor selection decisions46. Biased estimates of GEBVs as a result of ignoring dominance effects have been reported by Mohammadi and Sattaei Mokhtari41. In addition, Varona et al.47 stated that consequences of ignoring dominance effects may affect predictions of breeding values and can lead to the biased prediction of GEBVs, inbreeding depression, and performance of potential mates. A direct consequence of biased estimates of GEBVs of selection candidates is the erroneous ranking of top individuals. In Aliloo et al.45including dominance effects in the genomic evaluation model changed the ranking of the animals based on their GEBVs, so that the correlation of the ranking of the top animals in the two models containing and ignoring dominance effects was 0.9.

Increase in accuracy and decrease in MSEp and bias of GEBVs as a result of the decrease in the number of QTL underlying the trait have been reported by some authors including Coster et al.48 and Abdollahi-Arpanahi et al.49. By decreasing the number of QTL, the total genetic variance is divided between less QTLs and, therefore, the efficiency of methods to estimate such large QTL effects increases leading to increased accuracy and decreased MSEp and bias49,50.

Dispersion is often incorrectly referred to as “bias” in animal breeding literature. However, in the absence of bias, the expected value of dispersion is 151. A value of \(\:\widehat{d}\) close to one indicates better performance. Because \(\:\widehat{d}\)>1, there was under-dispersion (deflation) in the estimates of the genetic merit of the selection candidates. In the study by Alexandre et al.51a negative correlation between heritability and dispersion was observed, such that higher estimates of heritability were associated with overdispersion in the resulting GEBVs. Accuracy (or predictive ability) is currently the main statistic employed to compare genomic prediction methods. However, bias and dispersion of genomic predictions should be the matter of concern, especially if animals from different generations and with different amounts of information (e.g. progeny-tested and newborn animals) are among selection candidates52.

Several methods have been developed to estimate the effect of SNPs. These methods belong to parametric methods (such as GBLUP and Bayesian methods), semi-parametric methods (such as reproducing kernel Hilbert space, RKHS), and non-parametric methods (such as machine learning methods)7,12,52,53. A method with accuracy close to one, MSE close to zero, bias close to zero, and dispersion close to one is desirable for genomic evaluation46. Accordingly, in the current study, GBLUP, BayesB, and rrBLUPm6 showed a better predictive performance compared to other methods. Regression tree-based methods, in particular, RT showed poor performance and, therefore, are not recommended for genomic selection where dominance effects are ignored from genomic evaluation. Different methods have different assumptions about the distribution of the marker effects, the selection of covariates, and the genetic variances and (co)variances matrix. Different combinations of these assumptions modify the genetic variation explained by the markers, which directly reflects on the accuracy54. Moradi et al.55 compared the GBLUP and BayesB parametric methods, the semi-parametric method RKHS, and the non-parametric method RF in the genomic evaluation of traits with additive genetic architecture and reported that GBLUP and BayesB performed better than semi-parametric and non-parametric methods. Howard et al.7 with a simulation study, reported that if the genetic architecture of the trait is based on additive genetic effects, parametric methods (Bayesian methods) outperformed non-parametric (SVM) and semi-parametric (RKHS) methods, but by including dominance effects in the model, the accuracy of genomic prediction of non-parametric methods was higher than parametric methods. These reports together with our findings showed that where the genetic architecture of the traits includes only additive effects, or where dominance effects are present but ignored, parametric models such as GBLUP, Bayesian methods and rrBLUPm6 are superior to other models. But, where dominance effects are present and genomic evaluation model includes dominance component, non-parametric methods would be a good choice.

Conclusions

In general, the results of this study showed that when dominance effects were present, but were not included in the model, genomic evaluation of discrete threshold traits provides inaccurate, biased, and dispersed GEBVs. The degree of inaccuracy, bias, and dispersion had a direct relationship with the number of QTLs which had dominance effect. Among the models studied, GBLUP, BayesB, and rrBLUPm6 had better predictive performance and can be recommended for genomic evaluation of discrete threshold traits. To obtain accurate estimates of breeding values, using models containing both additive and dominance effects is recommended for genomic selection.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GEBV:

-

Genomic estimated breeding value

- BLUP:

-

Best linear unbiased prediction

- GBLUP:

-

Genomic best linear unbiased prediction

- QTL:

-

Quantitative trait loci

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- RT:

-

Regression tree

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- rrBLUP:

-

Ridge regression BLUP

- rrBLUPm6:

-

Ridge regression BLUP-method 6

- MSEp:

-

Mean square error of prediction

References

Ashoori-Banaei, S., Ghafouri-Kesbi, F. & Ahmadi, A. Comparison of regression tree-based methods in genomic selection. J. Genet. 100, 85 (2021).

Karimi, M., Ghafouri-Kesbi, F. & Zamani, P. Investigating the impact of dominance genetic effects on the accuracy of genomic evaluation. Res. Anim. Prod. 14, 145–153 (2023).

Spelman, R. & Garrick, D. Utilisation of marker assisted selection in a commercial dairy cow population. Livest. Prod. Sci. 47, 139–147 (1997).

Meuwissen, T. H., Hayes, B. J. & Goddard, M. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics 157, 1819–1829 (2001).

Schaeffer, L. Strategy for applying genome-wide selection in dairy cattle. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 123, 218–223 (2006).

Boison, S. et al. Strategies for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping to enhance genotype imputation in Gyr (Bos indicus) dairy cattle: comparison of commercially available SNP chips. J. Dairy Sci. 98, 4969–4989 (2015).

Howard, R., Carriquiry, A. L. & Beavis, W. D. Parametric and nonparametric statistical methods for genomic selection of traits with additive and epistatic genetic architectures. G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 4, 1027–1046 (2014).

Doublet, A. C. et al. The impact of genomic selection on genetic diversity and genetic gain in three French dairy cattle breeds. Genet. Selection Evol. 51, 1–13 (2019).

Hayes, B. J., Visscher, P. M. & Goddard, M. E. Increased accuracy of artificial selection by using the realized relationship matrix. Genet. Res. 91, 47–60 (2009).

Wang, C. et al. Bayesian methods for estimating GEBVs of threshold traits. Heredity 110, 213–219 (2013).

Baneh, H., Nejati-Javaremi, A., Rahimi-Mianji, G. & Honarvar, M. Genomic evaluation of threshold traits with different genetic architecture using bayesian approaches. Res. Anim. Prod. 8, 1029252 (2017).

Ahmadi, Z., Ghafouri-Kesbi, F. & Zamani, P. Assessing the performance of a novel method for genomic selection: rrBLUP-method6. J. Genet. 100, 24 (2021).

Varona, L., Legarra, A., Toro, M. A. & Vitezica, Z. G. Non-additive effects in genomic selection. Front. Genet. 9, 78 (2018).

Liu, P. et al. Hybrid performance of an immortalized F2 rapeseed population is driven by additive, dominance, and epistatic effects. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 815 (2017).

Jasouri, M., Zamani, P. & Alijani, S. Dominance genetic and maternal effects for genetic evaluation of egg production traits in dual-purpose chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 58, 498–505 (2017).

Ebrahimi, K., Dashab, G., Faraji-Arough, H. & Rokouei, M. Estimation of additive and non-additive genetic variances of body weight in crossbreed populations of the Japanese quail. Poult. Sci. 98, 46–55 (2019).

Sadeghi, S. A. T., Rokouei, M. & Faraji-Arough, H. Estimation of additive and non-additive genetic variances of average daily gain traits in adani goats. Small Ruminant Res. 202, 106472 (2021).

Sadeghi, S. A. T., Rokouei, M., Valleh, M. V., Abbasi, M. A. & Faraji-Arough, H. Estimation of additive and non-additive genetic variance component for growth traits in adani goats. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 52, 733–742 (2020).

Sun, C., VanRaden, P. M., Cole, J. B. & O’Connell, J. R. Improvement of prediction ability for genomic selection of dairy cattle by including dominance effects. PloS One. 9, e103934 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Evaluation of non-additive genetic variation in feed-related traits of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 96, 754–763 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Including dominance effects in the prediction model through locus-specific weights on heterozygous genotypes can greatly improve genomic predictive abilities. Heredity 128, 154–158 (2022).

Gianola, D. Theory and analysis of threshold characters. J. Anim. Sci. 54, 1079–1096 (1982).

Falconer, D. S. Introduction to quantitative geneticsPearson Education India,. (1996).

de Villemereuil, P. Quantitative genetic methods depending on the nature of the phenotypic trait. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1422, 29–47 (2018).

Roff, D. A., Stirling, G. & Fairbairn, D. J. The evolution of threshold traits: a quantitative genetic analysis of the physiological and life-history correlates of wing dimorphism in the sand cricket. Evolution 51, 1910–1919 (1997).

Roff, D. A. Evolution of threshold traits: the balance between directional selection, drift and mutation. Heredity 80, 25–32 (1998).

González-Recio, O. & Forni, S. Genome-wide prediction of discrete traits using bayesian regressions and machine learning. Genet. Selection Evol. 43, 1–12 (2011).

Ghasemi, M., Ghafouri-Kesbi, F. & Zamani, P. Genomic evaluation of threshold traits in different scenarios of threshold number using parametric and non-parametric statistical methods. J. Agricultural Sci. 161, 109–116 (2023).

Technow, F. R. & Package hypred Simulation of genomic data in applied genetics. University Hohenheim (2011).

Core Team, R. R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2013).

Porto-Neto, L. R., Kijas, J. W. & Reverter, A. The extent of linkage disequilibrium in beef cattle breeds using high-density SNP genotypes. Genet. Selection Evol. 46, 1–5 (2014).

VanRaden, P. M. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 91, 4414–4423 (2008).

Pérez, P. & de Campos, L. Genome-wide regression and prediction with the BGLR statistical package. Genetics 198, 483–495 (2014).

Piepho, H. et al. Efficient computation of ridge-regression best linear unbiased prediction in genomic selection in plant breeding. Crop Sci. 52, 1093–1104 (2012).

Schulz-Streeck, T., Estaghvirou, B. & Technow, F. rrBlupMethod6–Re-parametrization of RR-BLUP to allow for a fixed residual variance. (2012).

Therneau, T., Atkinson, B., Ripley, B. & Ripley, M. B. Package ‘rpart’. Available online: cran. ma. ic. ac. uk (2016). http://cran.ma.ic.ac.uk/web/packages/rpart/rpart.pdf (accessed on 20 April) (2015).

RColorBrewer, S. & Liaw, M. A. Package ‘randomforest’. University of California, Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA (2018).

Ridgeway, G. Generalized boosted models: A guide to the Gbm package. Update 1, 2007 (2007).

Legarra, A. & Reverter, A. Semi-parametric estimates of population accuracy and bias of predictions of breeding values and future phenotypes using the LR method. Genet. Selection Evol. 50, 1–18 (2018).

Mohammadi, Y. et al. The accuracy of genomic breeding value for production trait in Iranian Holstein dairy cattle using parametric and non-parametric methods. J. Anim. Prod. 18, 1–11 (2016).

Mohammadi, Y. & Sattaei Mokhtari, M. Genomic selection accuracy parametric and nonparametric statistical methods with additive and dominance genetic architectures. Res. Anim. Prod. 8, 161–167 (2018).

Nishio, M. & Satoh, M. Including dominance effects in the genomic BLUP method for genomic evaluation. PloS One. 9, e85792 (2014).

Morais Junior, O. P. et al. Relevance of additive and non-additive genetic relatedness for genomic prediction in rice population under recurrent selection breeding. (2017).

Yadav, S. et al. Improved genomic prediction of clonal performance in sugarcane by exploiting non-additive genetic effects. Theor. Appl. Genet. 134, 2235–2252 (2021).

Aliloo, H., Pryce, J. E., González-Recio, O., Cocks, B. G. & Hayes, B. J. Accounting for dominance to improve genomic evaluations of dairy cows for fertility and milk production traits. Genet. Selection Evol. 48, 1–11 (2016).

Macedo, F. L. et al. Bias and accuracy of dairy sheep evaluations using BLUP and SSGBLUP with metafounders and unknown parent groups. Genet. Selection Evol. 52, 47 (2020).

Varona, L., Legarra, A., Herring, W. & Vitezica, Z. G. Genomic selection models for directional dominance: an example for litter size in pigs. Genet. Selection Evol. 50, 1–13 (2018).

Coster, A., Bastiaansen, J. W., Calus, M. P., van Arendonk, J. A. & Bovenhuis, H. Sensitivity of methods for estimating breeding values using genetic markers to the number of QTL and distribution of QTL variance. Genet. Selection Evol. 42, 1–11 (2010).

Abdollahi-Arpanahi, R., Pakdel, A., Nejati-Javaremi, A. & Shahrbabak, M. Comparison of different methods of genomic evolution in traits with different genetic architecture. J. Anim. Prod. 15, 65–77 (2013).

Kasnavi, S. A., Aminafshar, M., Shariati, M. M., Kashan, N. E. J. & Honarvar, M. The effect of kernel selection on genome wide prediction of discrete traits by support vector machine. Gene Rep. 11, 279–282 (2018).

Alexandre, P. A. et al. Bias, dispersion, and accuracy of genomic predictions for feedlot and carcase traits in Australian Angus steers. Genet. Selection Evol. 53, 1–10 (2021).

Neves, H. H., Carvalheiro, R. & Queiroz, S. A. A comparison of statistical methods for genomic selection in a mice population. BMC Genet. 13, 1–17 (2012).

Sahebalam, H., Gholizadeh, M., Hafezian, H. & Farhadi, A. Comparison of parametric, semiparametric and nonparametric methods in genomic evaluation. J. Genet. 98, 1–8 (2019).

Andrade, L. R. B., d., Sousa, M. B., Oliveira, E. J., Resende, M. D. V. & Azevedo, C. F. d. Cassava yield traits predicted by genomic selection methods. PLoS One 14, e0224920 (2019).

AbdolahiArpanahi, R. Comparison of parametric and resampling methods in genetic evaluation of quantitative traits with different genetic structure. J. Anim. Prod. 19, 1–12 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Dr. F. Technow is gratefully acknowledged for helping us to work with Hypred package.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Farhad Ghafouri-Kesbi: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing-original draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghafouri-Kesbi, F. Consequences of ignoring dominance genetic effects from genomic selection model for discrete threshold traits. Sci Rep 15, 29693 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14877-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14877-1