Abstract

The aim of this case-control study was to evaluate the ability of digital health technology (DHT) to detect and quantify mobility alterations in late-onset Pompe Disease. The study enrolled eight subjects with Pompe Disease, including three young mildly affected/asymptomatic subjects, who underwent an extensive DHT mobility assessment and were contrasted to 52 matched controls. DHT enabled the detection of subtle mobility alterations, indicating a lower speed in walking, and worse performances in postural transition and turning in patients compared to controls. Interestingly, in the three mildly affected/asymptomatic cases, step time variability and step length showed detectable alterations compared to controls, despite scores within the normal range on clinical scales and timed tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pompe disease, also known as Glycogen storage disease type II (GSDII), is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a deficiency of the acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) enzyme, whose function is to hydrolyze glycogen to glucose in the lysosome1,2.

GSDII has been classified according to age at onset into severe infantile form and late-onset form (LO- GSDII) which presents a more heterogeneous involvement of respiratory and skeletal muscles2,3,4. Since 2006, the use of the recombinant enzyme alglucosidase alfa (Myozyme®/Lumizyme®) has demonstrated its efficacy in stabilizing motor and pulmonary function, leading to a life-changing scenario for both infantile and adult patients3,5. However, among LO-GSDII patients, a high level of variability in their responses to the treatment was observed, and many subjects experienced some degree of secondary decline after 3–5 years6. During the last decade, this led to several studies aimed at expanding the therapeutic options to include novel rhGAAs (avalglucosidase alfa), chaperone- enhanced rhGAA (cipaglucosidase), and even gene therapy7,8.

One of the main issues in managing LO-GSDII patients is the best way to assess the response to treatment because the sensitivity of the current clinical scales and timed tests does not seem optimal, especially in evaluating mild forms2,9.

Recent studies have supported the use of digital health technologies (DHTs) to assess subtle mobility changes in response to interventions in different clinical conditions10,11,12.

In this study we applied a comprehensive DHT assessment of gait, turning, and postural transition to detect subtle mobility impairment in LO-GSDII patients and investigate a subgroup of mildly affected or asymptomatic LO-GSDII subjects. The study demonstrated that step length and time variability are altered in all patients, including those who are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms. Furthermore, subjects with mild to moderate symptoms also exhibited alterations in the maximal velocity during a task of postural transition and angular velocity during turning when compared to matched controls.

Patients and methods

Clinical assessment

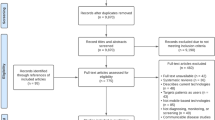

This prospective study included patients with a genetic diagnosis of LO-GSDII followed at the ERN-Euro NMD Center for Neuromuscular Diseases in Brescia, Italy (Unit of Neurology and NeMO-Brescia Clinical Center for Neuromuscular Diseases, ASST Spedali Civili and University of Brescia) under enzyme-replacement treatment (ERT) with alglucosidase alpha.

Neurologically healthy controls were recruited from patients’ families and from healthy volunteers and were matched for age with the patients. The following inclusion criteria were applied for both groups: (i) age over 18 years old, (ii) ability to walk without aids, (iii) lack of medical conditions or medication with potential impact on gait and mobility (including other neurological diseases, orthopaedic issues), other than LO-GSDII for the case group. No limitations were imposed regarding the utilization of non-invasive ventilatory devices.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Brescia Hospital, Brescia, Italy (DMA study, NP 1471). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Each LO-GSDII patient underwent an extensive clinical protocol including several clinical scales used in clinical trials and observational studies. Functional endurance was assessed by the 6-minute walking test (6MWT), which measures aerobic capacity by the distance (meters) walked in 6 min and is a well-known secondary outcome measure in clinical trials for GSDII7. The motor performances in daily life were evaluated by the Gardner-Medwin-Walton (WGM) scale, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, and Gait, Stairs, Gower, Chair score (GCSG) scale9. WGM scale is a validated score ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating the normal conditions and 10 the inability to conduct any activity. GSGC scale has recently been introduced and investigate the performances in four motor tasks (Gait by walking or 10 m, climbing 4 steps on a stair, Gower’s manoeuvre, rising from a Chair), ranging from 4 (normal performance) to 27 (worst performance in non-ambulatory patients).

The daily life impact of the disease was assessed by Rasch-Built Pompe-specific Activity scale (R-Pact), Pompe Disease Symptom Scale (PDSS) and Pompe Disease Impact Scale (PDIS). These scales are simple self-report questionnaires based on daily or social activities that may be affected by the disease. The R-Pact consists of 18 items in order of increasing difficulty and the score for each item is defined as 0 = unable to perform, 1 = able to perform with difficulty, 2 = able to perform without difficulty13. The PDSS is based on 12 items with specific focus on fatigue, in which patients rate the severity of symptoms in the last 24 h from 0 to 1014. Nevertheless, the 15-item PDIS questionnaire provides a picture of mood and mobility-related activities over the previous 24 hours9,14.

Digital health technology assessment

The RehaGait® system consists of three mobile inertial sensors (dimensions: 60 × 15 × 35 mm); each sensor comprises a 3-axis accelerometer (± 16 g), a 3- axis gyroscope (± 2000 °/s) and a 3-triaxial magnetometer (± 1.3 125 Gs). The sensors were attached to the lateral side of each shoe using special straps and at the level of the fifth lumbar spine segment close to the centre of mass to measure linear acceleration, angular velocity and the magnetic field at a sampling rate of 100 Hz15.

Raw data were processed using Matlab R2022b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). To analyse gait parameters the raw data of the IMU from the lower back was used. As stated in the method session, only variables with a percentage of missing data lower than 5% were considered. Outliers were defined by a value higher or lower than 3 standard deviations of the disease-specific group and were excluded from the analyses. As described in the references, the raw accelerometer and gyroscope data were processed to first detect the gait events16,17. Step time was defined as the time between two consecutive heel strikes, step time variabilities were calculated extracting standard deviation (SD) from all steps18. Step length was calculated as previously reported by Welzel and coauthors19. 6MWT-Fatigability was specifically evaluated by contrasting steps-4-104 with the last 100 steps detected during the 6 min walking test. Asymmetry was defined as the average absolute difference between left and right steps for each walking pass. The parameters included in the final analyses were duration of TUG, duration of turns, peak and mean angular velocities (in degrees per second), for the whole turning. Mean values from the clockwise and counterclockwise turns were used20,21. Postural transition digital assessment included PT duration, speed and angular velocity based on vertical displacement of the IMU placed on the low bac16,22.

Statistical analysis

Differences in demographic and clinical parameters between participants with LO-GSDII and controls were not normally distributed and non-parametric tests adjusted for age and sex were used for all analyses. The sample size was calculated using the g*power 3.1.9.4 software, with a 0.05 alpha level, an 80% power (Cohen 1988), and an effect size of 0.85 to account for the small sample size and a 3:1 ratio. The model also accounted for the non-normal distribution between the groups, given the small sample size. Based on these assumptions, the number of calculated matched controls for eight patients was 24 subjects; the size was doubled in order to potentially expand the analyses on a subset of symptomatic vs. asymptomatic patients. For the secondary analyses focused on mildly affected/asymptomatic cases, a younger group of controls (n = 21, age 27 ± 1.9) was thus selected. All analyses were 2-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

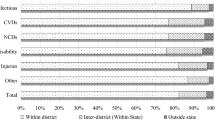

Eight LO-GSDII patients (mean age 43 years, Female 3/8, 37%), five symptomatic and three mildly affected/asymptomatic and 52 matched controls (mean age 44 years, female 38%) entered the study (Table 1).

The five symptomatic patients presented heterogeneous motor impairment, as scored by clinical scales and 6MWT. Out of the three mildly affected/asymptomatic patients, only one was diagnosed because of mild fatigability during adolescence, while the other two were asymptomatic at diagnosis (incidental finding of hyperCKemia, diagnosis in first grade relative). Asymptomatic patients at diagnosis later started ERT due to magnetic resonance imaging of muscle fatty substitution. At the clinical scale and timed test, all mildly affected/asymptomatic subjects scored within the normal range except one patient with borderline GSGC score. Differences in digital parameters have been summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

In the walking task, LO-GSDII patients exhibited a lower number of steps with a longer step time, shorter step length and increased step time variability, compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 1, Table 2). The comparison between the first and last 100 walking bouts showed similar trends in patients and controls during the 6MWT task (Table 3).

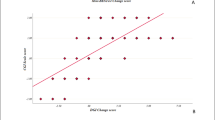

In the turning task, LO-GSDII patients exhibited lower angular and peak velocities, and a slightly higher turning duration, than controls. In the postural transition task during TUG, LO-GSDII patients showed a longer duration of standing. Moreover, in the Five Times sit-to-stand Test, they showed lower extension maximal velocity during the standing up phases and a longer duration of the standing phases between the transitions (Supplementary Fig. 1, Table 4). Clinical scores correlated significantly with peak angular velocity of turning, sit to stand duration of the Five Times sit-to-stand Test and number of steps of the 6MWT (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Mildly affected/asymptomatic LO-GSDII subjects exhibited higher step time variability and lower step length, compared to age-matched controls, whereas no significant differences in the number of steps and step time were detected (Table 5). In turning and sit-to-stand tasks, a trend towards reduced peak and normal angular speed and longer task duration was observed (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

LO-GSDII is a debilitating, progressive disorder that imposes significant challenges on affected individuals and their families23,24. Characterized by insidious onset and gradual progression, LO-GSDII primarily affects the skeletal and respiratory muscles, leading to increased morbidity and decreased quality of life23,24. In this context, the development and implementation of robust outcome measures is essential for accurately tracking disease progression, evaluating therapeutic efficacy, and ultimately improving patient care and outcomes.

One of the foremost needs of LO-GSDII outcome measures is their sensitivity to detect subtle changes over time. LO-GSDII progresses slowly, and often the incremental decline in muscle strength or respiratory function can be missed by less sensitive measures25,26. Tools that can capture these minute changes are useful for early intervention and for assessing the true impact of therapeutic strategies. Without such sensitivity, we risk underestimating the disease’s progression and overestimating the efficacy of interventions.

To date, outcome measures used in Pompe Disease, as derived from clinical trials, include functional tests such as the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and the timed up-and-go (TUG) test, alongside assessments of activities of daily living (ADLs), respiratory function assessments (forced vital capacity), and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) able to detect patients’ perceptions of their own health, symptoms, and the impact of the disease on daily life7,27,28,29,30.

As new therapies emerge, outcome measures must evolve to capture their specific impacts. This adaptability ensures that the measures remain relevant and continue to provide meaningful data that reflects the benefits or limitations of novel treatments.

Digital parameters obtained by DHTs have recently demonstrated their validity as outcome measures in several conditions, including movement disorders and Duchenne muscular dystrophy10,11,12,13. In LO-GSDII, only one preliminary study has been conducted in this area using FitBit OneTM data to track the number of steps taken by moderately and severely affected patients14. The study showed a reduction in total step count in LO-GSDII, with a reasonable correlation with disease severity and disease duration.

To our best knowledge, ours is the first study to use a comprehensive DHT assessment to study motor impairment in LO-GSDII. The results of this small pilot study may be relevant for the research community, which is still searching for reliable outcome measures2,6,14,25,26. It shows a wide range of alterations in mobility among both fully symptomatic and mildly affected/asymptomatic subjects.

Considering the total number of LO-GSDII subjects, significant changes in the walking task (lower number of steps, longer step time, shorter step length, and increased step time variability), turning task (lower angular and peak velocities, and slightly higher turning duration), and postural transition task (longer duration of standing) were observed compared to controls. A significant correlation with clinical scores was found for peak angular velocity of turning, sit-to-stand duration of the Five Times sit-to-stand Test, and number of steps of the 6MWT.

Interestingly, our study went further to evaluate mildly affected or asymptomatic LO-GSDII patients in a supervised setting, focusing on a wider range of components, namely walking, turning, and postural changes. Gait analysis in this subgroup of subjects showed reduced step length and increased variability, despite normal scores on clinical scales and timed motor tests. Overall, the variability of walking parameters in LO-GSDII was slightly increased but substantially like the control group between the first and last 100 steps. This may suggest that the differences in walking parameters are related to a stable deficit undetectable by routine scores rather than fatigability. Turning and postural transition tasks also revealed subtle changes that could be related to axial muscle weakness, even though they did not reach statistical significance in this subgroup.

Our findings demonstrate that digital motor metrics potentially have the capacity to detect subtle motor impairments in individuals with mild or asymptomatic Pompe disease, including those not identified by conventional clinical scales. Digital metrics may provide a richer and continuous readout of motor performance that could enhance disease monitoring and – if supported byu longitudinal studies- progression tracking. In conditions such as Pompe disease, where early therapeutic intervention can modify the course of the disease, digital health assessments could serve as valuable tools to facilitate more timely and personalised treatment decisions. These tools have the potential to reduce the frequency of invasive or time-consuming procedures by offering reliable remote assessments, thereby improving patient care and potentially reducing healthcare burden31,32.

However, while digital metrics show significant promise, a critical next step will be establishing clinically meaningful thresholds that define when a detected digital change reflects true disease progression or necessitates clinical action. Furthermore, it should be noted that our cross-sectional data is not sufficiently comprehensive in terms of capturing the evolution of the disease. Ongoing Longitudinal studies are essential to validate the prognostic value of digital assessments, determine their sensitivity to change over time, and define their role in guiding treatment decisions.

The small number of subjects remains the main limitation of this study, although we have demonstrated the validity of DHT assessment even with a limited sample size and high heterogeneity of motor involvement. The sensitivity of promising digital markers such extension max velocity in 5-times raising from chair, angular velocity in turning transitions and step alterations in length, time and time variability will be investigated on a larger on-going longitudinal study. We would also extend these measures to unsupervised settings, which are known to be more effective and sensitive to detect multiple symptoms in different conditions, as demonstrated in Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and even healthy aging17,33.

Notwithstanding this limitation, our preliminary results suggest that wearable technologies can identify subtle walking abnormalities also in mildly affected or asymptomatic patients not otherwise evident by usual clinical evaluation. They may have important implications for management, follow-up, and treatment decisions in clinical practice. Importantly, our results suggest that DHT deserve to be evaluated as a promising outcome measure for clinical trials.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the correspondent author, without undue reservation.

References

Lim, J. A., Li, L. & Raben, N. Pompe disease: from pathophysiology to therapy and back again. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00177 (2014).

Labella, B. et al. A comprehensive update on Late-Onset Pompe disease. Biomolecules 13 (9), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13091279 (2023).

Kishnani, P. S. et al. Recombinant human acid α-glucosidase: major clinical benefits in infantile- onset Pompe disease. Neurology. 68(2):99–109 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04. Erratum in: Neurology. 71(21):1748 (2008).

Angelini, C. & Engel, A. G. Comparative study of acid Maltase deficiency. Biochemical differences between infantile, childhood, and adult types. Arch. Neurol. 26 (4), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1972.00490100074007 (1972).

Kuperus, E. et al. Long-term benefit of enzyme replacement therapy in Pompe disease A 5-year prospective study. Neurology 89 (23), 2365–2373. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004711 (2017).

Harlaar, L. et al. Large variation in effects during 10 years of enzyme therapy in adults with Pompe disease. Neurology 93 (19), e1756–e1767. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008441 (2019).

Diaz-Manera, J. & COMET Investigator Group. Safety and efficacy of avalglucosidase alfa versus alglucosidase alfa in patients with late-onset Pompe Disease (COMET): a phase 3, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 20(12):1012–1026 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00241-6. Erratum in: Lancet Neurol. 21(4):e4 (2022).

Schoser, B. & Laforet, P. Therapeutic thoroughfares for adults living with Pompe disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 35 (5), 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000001092 (2022).

Angelini, C. Exercise, nutrition and enzyme replacement therapy are efficacious in adult Pompe patients: report from EPOC consortium. Eur. J. Transl Myol. 31 (2), 9798. https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2021.9798 (2021).

Servais, L. et al. First regulatory qualification of a digital primary endpoint to measure treatment efficacy in DMD. Nat. Med. 29 (10), 2391–2392. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02459-5 (2023).

Artusi, C. A. et al. Implementation of mobile health technologies in clinical trials of movement disorders: underutilized potential. Neurotherapeutics 17 (4), 1736–1746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-020-00901-x (2020).

Bortolani, S. et al. Technology outcome measures in neuromuscular disorders: A systematic review. Eur. J. Neurol. 29 (4), 1266–1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15235 (2022).

Van der Beek, N. A., Hagemans, M. L., van der Ploeg, A. T., van Doorn, P. A. & Merkies, I. S. The Rasch- built Pompe-specific activity (R-PAct) scale. Neuromuscul. Disord. 23 (3), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2012.10.024 (2013).

Hamed, A., Curran, C., Gwaltney, C. & DasMahapatra, P. Mobility assessment using wearable technology in patients with late-onset Pompe disease. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 70. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0143-8 (2019).

Geritz, J. et al. Motor, cognitive and mobility deficits in 1000 geriatric patients: protocol of a quantitative observational study before and after routine clinical geriatric treatment - the ComOn- study. BMC Geriatr. 20 (1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1445-z (2020).

Pham, M. et al. Validation of a step detection algorithm during straight walking and turning in patients with parkinson’s disease and older adults using an inertial measurement unit at the lower back. Front. Neurol. 8, 457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00457 (2017).

Pilotto, A. et al. Unsupervised but not supervised gait parameters are related to fatigue in parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1279722. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1279722 (2023).

Paraschiv-Ionescu, A. et al. Locomotion and Cadence detection using a single trunk-fixed accelerometer: validity for children with cerebral palsy in daily life-like conditions. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-019-0494-z (2019).

Welzel, J. et al. Step length is a promising progression marker in parkinson’s disease. Sens. (Basel). 21 (7), 2292. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072292 (2021).

Van Uem, J. et al. Health-Related quality of life in patients with parkinson’s disease– A systematic review based on the ICF model. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 61, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.11.014 (2016).

Zatti, C. et al. Turning alterations detected by mobile health technology in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10 (1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00682-6 (2024).

Atrsaei, A. et al. Postural transitions detection and characterization in healthy and patient populations using a single waist sensor. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 17 (1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-020-00692-4 (2020).

Schoser, B. et al. The humanistic burden of Pompe disease: are there still unmet needs? A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 17 (1), 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0983-2 (2017).

Hagemans, M. L. et al. Late-onset Pompe disease primarily affects quality of life in physical health domains. Neurology 63 (9), 1688–1692. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000142597.69707.78 (2004).

Lachmann, R. & Schoser, B. The clinical relevance of outcomes used in late-onset Pompe disease: can we do better? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8, 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-160 (2013).

Claeys, K. G. et al. Minimal clinically important differences in six-minute walking distance in late- onset Pompe disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19 (1), 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03156-3 (2024).

Van der Ploeg, A. T. et al. A randomized study of alglucosidase Alfa in late-onset pompe’s disease. N Engl. J. Med. 362 (15), 1396–1406. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0909859 (2010).

Hamed, A. et al. Qualitative interviews to improve patient-reported outcome measures in late- onset Pompe disease: the patient perspective. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16 (1), 428. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-02067-x (2021).

Kishnani, P. S. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Avalglucosidase Alfa in Patients With Late-Onset Pompe Disease After 97 Weeks: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. Jun 1;80(6):558–567. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.0552

Toscano, A. et al. Effect of avalglucosidase Alfa on disease-specific and general patient-reported outcomes in treatment-naïve adults with late-onset Pompe disease compared with alglucosidase Alfa: meaningful change analyses from the phase 3 COMET trial. Mol. Genet. Metab. 141 (2), 108121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2023.108121 (2024).

Maulet, T. et al. Determinants and characterization of locomotion in adults with Late-Onset Pompe disease: new clinical biomarkers. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 10 (5), 963–976. https://doi.org/10.3233/JND- (2023).

Porcino, M. et al. Management of presymptomatic juvenile patients with late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD). Neuromuscul. Disord. 47, 105277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2025.105277 (2025).

Warmerdam, E. et al. Long-term unsupervised mobility assessment in movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 19 (5), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30397-7 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in this study for their time and willingness to contribute this research. Andrea Pilotto, Beatrice Labella, Andrea Rizzardi, Chiara Trasciatti, Filomena Caria, Barbara Risi, Simona Damioli, Emanuele Olivieri, Lucia Ferullo, Loris Poli, Alessandro Padovani and Massimiliano Filosto are part of the ERN Euro NMD, HCP ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy.

Funding

The study was partially financially supported for the assessment of controls by the Airalzh Foundation AGYR2021 Life-Bio Grant, The LIMPE-DISMOV Foundation Segala Grant 2021, the H2020 IMI IDEA- FAST (ID853981), Italian Ministry of Health, Grant/Award Number: RF-2018-12366209 and PNRR- Health PNRR-MAD-2022-12376110.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Pi., B.L., A.R., C.Z., W.M., A.Pa. and M.F. contributed to the conception and design of the study; A.Pi, B.L., A.R., C.Z., C.H., R.R., J.G., S.C.P, E.O., L.F., L.P., W.M and A.Pa. contributed to the acquisition and analyses of data; A.Pi., B.L., A.R., C.Z., C.H., R.R., F.C., B.R., S.D., W.M., A.Pa and M.F contributed to drafting the text; A.Pi., A.R., C.Z., C.T., C.H. and R.R contributed to statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Andrea Pilotto received grant support from Airalzh Foundation AGYR2021 Life-Bio Grant, The LIMPE-DISMOV Foundation Segala Grant 2021, the Italian Ministry of University and Research PRIN COCOON (2017MYJ5TH) and PRIN 2021 RePlast, the H2020 IMI IDEA-FAST (ID853981), Italian Ministry of Health, Grant/Award Number: RF-2018-12366209 and PNRR-Health PNRR-MAD-2022-12376110.Walter Maetzler receives or received funding from the European Union, the German Federal Ministry of Education of Research, German Research Council, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Neuroalliance, Lundbeck, Sivantos and Janssen. He received speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Bayer, BIAL, GlaxoSmithKline, Heel, Licher MT, Rölke Pharma, Takeda and UCB, was invited to Advisory Boards/Consultancies of Abbvie, Aptar Digital Health, Atheneum, Biogen, Kyowa Kirin, Lundbeck and Pfizer, is an advisory board member of the Critical Path for Parkinson’s Consortium and the MDS e-Diary Working Group, and an editorial board member of Geriatric Care. He is a member of the MDS Technology Working Group.Alessandro Padovani received grant support from Ministry of Health (MINSAL) and Ministry of Education, Research and University (MIUR), IMI H2020 initiative (IMI2-2018-15-06).Massimiliano Filosto received grant support from Telethon Italy Foundation and Italian Ministry of University and Research PRIN PNRR 2022.The other authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

The Ethics Committee approved the Brescia Hospital’s research protocol (NP 3710). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pilotto, A., Labella, B., Rizzardi, A. et al. Extensive digital health technology assessment detects subtle motor impairment in mild and asymptomatic Pompe disease. Sci Rep 15, 29798 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14993-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14993-y