Abstract

This study explored the effects of a virtual forest environment compared to a virtual urban setting on key psychological factors, including self-compassion, self-protection, self-criticism, and stress. Designed as a pilot randomized controlled trial, the study included 28 adult participants who were randomly assigned to either the virtual forest or virtual city condition. Results from the Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism Scale indicated a significant increase in state self-compassion and a decrease in state self-criticism within the Forest Group. Notably, state self-criticism also decreased in the City Group. However, participants in the City Group experienced a significant increase in perceived stress and a decline in trait compassion, as measured by the Sussex-Oxford Compassion Scale. These findings suggest that virtual forest bathing may serve as a valuable therapeutic intervention, promoting self-compassion – recognized as a transdiagnostic factor for mental well-being – while reducing self-criticism, a known transdiagnostic factor of psychopathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Previous research has documented the stress-reducing and restorative effects of exposure to natural environments, often referred to as “forest bathing” or “nature therapy,” with benefits including reduced cortisol levels, slower heart rate, and enhanced mood1,2,3,4. However, not everyone has equal access to nature, particularly those living in urban environments or with limited mobility. Virtual reality offers a promising alternative, enabling individuals to experience immersive simulations of natural settings and potentially reap similar psychological and physiological benefits4,5.

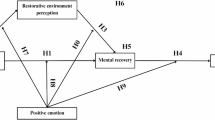

Beyond stress reduction, the potential link between forest bathing and psychological constructs such as self-compassion and self-criticism can be understood through several interconnected mechanisms. Exposure to natural environments has been found to reduce rumination and mental fatigue, facilitate emotional regulation, and support mindfulness – all of which are associated with increased self-compassion and reduced self-criticism6. According to Attention Restoration Theory7 and Stress Recovery Theory8, natural settings promote a sense of calm and psychological safety, creating conditions conducive to self-acceptance and reduced self-judgment. Compassion-focused theories9 further suggest that feelings of connectedness and safety (often evoked in nature) activate the affiliative system, thereby fostering self-compassion and inhibiting self-attacking tendencies.

A recent systematic review10 identified only a limited number of studies directly examining forest bathing in relation to self-compassion, self-protection, and self-criticism. Nevertheless, existing evidence supports the idea that forest exposure (whether real or virtual) can reduce negative psychological states, such as rumination and self-criticism, while enhancing positive processes, including introspection, mindfulness, and compassionate self-relating.

Virtual and augmented reality technologies thus offer a unique opportunity to expand the reach of these interventions. Their ability to simulate naturalistic, soothing environments with precision makes them ideal for mental health and wellbeing applications11. Unlike traditional nature exposure, VR enables the creation of highly immersive, customizable scenarios that are otherwise difficult to access or replicate in real-world conditions12. The distinctiveness of our research lies in leveraging custom-designed virtual environments to explore these restorative and self-transformative potentials.

The aim of the research study

Forest bathing, traditionally performed by walking in natural environments, was adapted for virtual reality to compare its effects to those of urban environments, as approximately 56% of the global population resides in urban areas13.

This study aimed to explore a gap in the existing research by comparing the effectiveness of two distinct virtual environments – a virtual forest and a virtual city – on the psychological constructs of self-compassion, self-protection, self-criticism, and stress. This approach seeks to expand the potential applications of virtual reality technology in promoting mental health and well-being, while simultaneously creating a reproducible research environment for future research.

Methods

Study design

This research was designed as a pilot study, with a randomized controlled trial and within-between subject design. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling through social media platforms and the snowball sampling method, whereby student networks were leveraged to expand participation.

Research study and procedure

The research sample was collected via social media using the snowball technique. The study consisted of 28 adult participants (18 + years old) were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups who completed two virtual reality sessions in the period of one week. Twenty-four of the participants completed a follow-up assessment, two months after their second exposure via online questionnaire (Fig. 1). Participants were excluded if they had a psychiatric diagnosis. Simultaneously prior to the start of the study, participants were informed about potential contraindications of virtual reality through the informed consent form. The experimental Forest Group (N = 14) was exposed to a virtual forest environment, while the control group, the City Group (N = 14), was exposed to a virtual city environment. No participants experienced both environments. Each session lasted 30 min, during which the participants were seated on a static 360-degree swivel chair. Our environments were 3D models (providing depth and immersion) of a forest (Pic. 3 and 4) and a city (Pic. 5 and 6) that provided participants with a 360-degree view of their surroundings in virtual reality In the forest environment, participants were exposed to natural sounds such as rustling leaves, wind, and birdsong, and could observe dynamic elements like swaying tree canopies, birds in flight, and the occasional squirrel. In contrast, the urban setting included distant traffic noise, human activity, and visual cues such as passing cars, changing traffic lights, and rats near garbage bins. The neutral room lacked ambient sounds but included interactive objects on a table, which participants could knock over to enhance embodiment and presence. Each participant spent 2 min in neutral room, before their exposure to either of the environments, so they would get acclimatised to virtual reality (Pic. 1 and 2). To deploy the VR application developed in Unity14, the Steam15 platform was utilized. Data collection was conducted from March to June 2024.

Data collection was occasionally disrupted by environmental and technical factors. The room was not soundproofed, and external noise may have briefly distracted participants. Minor technical issues included calibration errors, sensor dropouts, and intermittent malfunctions of the VR system, chest strap, or motion trackers. Additional difficulties such as overheating, lag, and a loose cable affected equipment performance, while the VR headset’s weight and high room temperature may have reduced participant comfort during longer sessions.

These types of technical issues are consistent with previous VR research, which reports minor disruptions in approximately 15–30% of sessions and major failures requiring data exclusion in fewer than 10% (Freeman et al., 2017; Wiederhold & Riva, 2019). In our sample, 6% of participants experienced minor technical difficulties, all of which were resolved during the session. Anticipating the possibility of such issues, we carefully documented the exact timing of each disruption and excluded data from the affected time segments. As a result, no participants (0%) were excluded due to unresolved technical problems.

The sociodemographic analysis revealed that the mean age for the Forest Group was 30.0 years (SD = 11.8), and 33.6 years (SD = 12.6) for the City Group. The majority (18) of participants identified as women. There were 10 women (71.4%) in the Forest Group and 8 (57.1%) in the City Group; and 4 men (28.6%) in the Forest Group and 5 men (35.7%) in the City Group. One City Group participant identified as non-binary. Educational levels varied, with the majority holding a bachelor or postgraduate degree. In the Forest Group 4 (14.3%) had completed High School education, 3 (10.7%) had a Bachelor’s degree: 5 (17.9%) a Master’s, and 2 (7.1%) a doctorate. The City Group contained 4 (14.3%) High School graduates, 4 (14.3%) with a Bachelor’s, 3 (10.7%) a Master’s, and 3 (10.7%) a doctorate.

Research measures

Data were collected using the following scales:

The self-compassion and self-criticism scales

The Slovak version16 of the Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism Scales (SCCS;17 is a 30-item scale that requires respondents to vividly imagine five scenarios that may evoke self-compassion or self-criticism. Responses are recorded on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). It comprises two subscales: Self-Compassion (SCO) and Self-Criticism (SCR). The Slovak version was validated on a sample of 514 adults and has internal consistency ranging from 0.75 to 0.85 and a two-factor structure16.

The perceived stress scale

The Slovak version18 of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10;19 is a 10-item questionnaire measuring perceived stress on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). It has two subscales: perceived helplessness and perceived self-efficacy. It was tested on 482 helping professionals and showed good internal consistency (α = 0.79); a confirmatory factor analysis indicated a two-factor structure.

The scale for interpersonal behaviour

The Slovak version20 of the short Scale for Interpersonal Behaviour (s-SIB;21 was used to measure self-protection with a 25-item subset focused on behaviour. Participants rated performance (frequency of behaviour) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never/not at all, 5 = always/extremely). The Slovak version was validated on 590 adults and demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.93–0.94; McDonald’s ω = 0.95). Support was found for using the total score for assertiveness as well as its subscales – Positive Assertion, Negative Assertion, Expression of and Dealing with Personal Limitations, and Initiating Assertiveness.

The Sussex-oxford compassion scales

Another measure used was the Slovak version22 of the Sussex-Oxford Compassion Scales (SOCS;23. The scales contain two 20-item versions, Self-Compassion (SOCS-S) and Other-Compassion (SOCS-O), each assessing five subscales – recognition of suffering, universality, empathy, tolerance, and motivation – using a 5-point Likert scale. The Slovak adaptation, validated on 123 adults, demonstrated high internal consistency (SOCS-O: α = 0.93; SOCS-S: α = 0.89) and supported a two-level model of self-compassion, encompassing rational and emotional/behavioural dimensions.

The forms of self-criticizing/attacking and self-reassuring scale

The Slovak version24 of The Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS;25 provided a 22-item scale, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all like me, 5 = very much like me) that measures three dimensions: Inadequate Self (IS), Hated Self (HS), and Reassured Self (RS). The Slovak validation, conducted on 1181 adults, confirmed a three-factor structure and high internal consistency (α = 0.75–0.85), indicating suitability for use in identifying highly self-critical individuals.

The nature exposure scale

The Nature Exposure Scale (NES;26, integrated with the Retrospective Nature Exposure Scale II (RNES-II;27 was adapted for the Slovak population28, excluding items related to physical activity. Both scales assess nature exposure in daily life and leisure time in present as well as in childhood using a 5-point Likert scale. The original NES26 showed moderate reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.69), and the RNES-II27 demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.85).

The Igroup presence questionnaire

Lastly, we translated the General Presence item: “In the computer-generated world, I had a sense of ‘being there’29” from the Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ;30,31,32 into Slovak for measuring perceived presence in virtual reality. The full IPQ30,31,32 consists of 14 items across four subscales: Spatial Presence, Engagement, General Presence, and Reality. Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much), assessing participants’ sense of presence in virtual environments. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the IPQ30,31,32 is 0.85.

Data analysis

Data were analysed with Jamovi33, using non-parametric mixed ANOVA (Friedman test) to assess differences between pre-test and post-test scores. To compare differences between groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed, with Bonferroni correction applied to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Results

The Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism Scale (SCCS) revealed significant improvement in the Forest Group, with state self-compassion (SCCS+) increasing from a baseline mean of 58.1 (SD = 17.7) to 65.7 (SD = 19.7), and state self-criticism (SCCS-) decreasing from 51.8 (SD = 22.9) to 40.4 (SD = 17.6). These changes were statistically significant (χ2(1) = 7.14, p = 0.008 for SCCS+; χ2(1) = 13.0, p < 0.001 for SCCS-). In the City Group, the state self-criticism scores decreased significantly (χ2(1) = 7.14, p = 0.008), from 50.9 (SD = 14.6) to 42.5 (SD = 14.3), while state self-compassion scores showed no significant change.

The perceived stress scale (PSS-10) did not change significantly in the Forest Group (χ2(1) = 0.333, p = 0.564), with scores moving from 17.9 (SD = 5.68) to 18.2 (SD = 4.28). However, stress levels increased significantly in the City Group, rising from a baseline mean of 17.8 (SD = 4.21) to 19.4 (SD = 3.97; χ2(1) = 4.57, p = 0.033). This imply that the virtual forest environment did not affect stress, whereas the urban environment may have contributed to a slight increase in perceived stress among participants.

Scale for Interpersonal Behavior – Short Form (s-SIB) scores remained stable significantly in both of the two groups. In the Forest Group (χ2(1) = 0.333, p = 0.564), χ2(1) = 0.00, p = 1.000 for the City Group.

The Forms of Self-Criticising/Attacking & Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS) scores showed no significant differences across sessions for either group, suggesting that the virtual reality environments did not increase or alleviate these traits in the short term. In the Forest Group, FSCRS + remained nearly identical (29.4 to 29.6; χ2(1) = 0.818, p = 0.366) and FSCRS- slightly decreased (32.9 to 31.5; χ2(1) = 0.0769, p = 0.782). Similarly, in the City Group, FSCRS + changed from 31.0 to 30.1 (χ2(1) = 0.692, p = 0.405) and FSCRS- from 32.6 to 30.7 (χ2(1) = 1.92, p = 0.166).

Scores for trait compassion and self-compassion, measured by the Sussex-Oxford Compassion Scale (SOCS-S for ‘self’ and SOCS-O for ‘others’), produced contrasting results. No significant changes were noted in SOCS-S for either group (χ2(1) = 1.33, p = 0.248 for the Forest Group; χ2(1) = 0.400, p = 0.527 for the City Group). SOCS-O scores in the City Group decreased significantly (χ2(1) = 6.23, p = 0.013), with means dropping from 81.2 (SD = 8.96) to 77.9 (SD = 7.88; p = 0.007). In contrast, SOCS-O scores in the Forest Group did not change significantly (χ2(1) = 0.08, p = 0.782), with means remaining stable at 76.6 (SD = 9.21) and 76.6 (SD = 6.30; p = 0.793). This decline suggests that the urban environment may have negatively influenced participants’ compassion to others, while the forest environment appeared to sustain it.

Perceived presence in the virtual reality environments, measured by a single item from IPQ30,31,32, remained consistent across the sessions in both groups, suggesting consistent levels of perceived presence across sessions (χ²(1) = 2.00, p = 0.157 for Forest group; χ2(1) = 0.111, p = 0.739 for City group).

To further explore group differences, Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to compare SOCS scores between the Forest and City groups at each time point. These analyses revealed no significant differences between groups at either pre-test (SOCS-S: U = 78.5, p = 0.382; SOCS-O: U = 76.5, p = 0.334) or post-test (SOCS-S: U = 88.5, p = 0.678; SOCS-O: U = 93.5, p = 0.854). To control for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni correction was applied to the 18 Mann-Whitney U tests conducted. After adjustment, none of the comparisons remained statistically significant (all corrected p-values ≥ 1.000).

Discussion

This study served to lay the groundwork for further exploration of this issue. By examining how different environmental exposures influence self-compassion, self-protection, self-criticism and stress, the study adds to the growing body of evidence that nature-based settings may foster mental health benefits. The results suggest that the virtual forest environment improves state self-compassion and reduces state self-criticism, with no effect on stress, trait self-criticism, self-compassion, or compassion to others. In contrast, the virtual city environment demonstrated mixed effects, reducing state self-criticism and trait compassion to others and increasing stress. These findings indicate nature-inspired virtual reality interventions may have counselling and therapeutic benefits with contrasting psychological impacts to urban virtual settings.

This research also introduces an innovative methodological approach by employing custom-designed virtual environments that enable controlled, replicable comparisons between natural and urban settings. By simulating these conditions through immersive VR, the study provides a novel way to investigate the psychological impacts of environmental exposure.

The research findings provide insights into the interplay between self-compassion, self-criticism, stress, and interpersonal behaviours in different virtual environments. The observed increase in state self-compassion and reduction in state self-criticism in the Forest Group align with previous research findings emphasizing the role of self-compassion in fostering emotional resilience and reducing negative self-evaluative tendencies34,35. The significant improvements in state self-compassion and decrease in self-criticism suggest that the virtual forest environment may act as a restorative intervention by enhancing self-compassionate states and mitigating self-critical tendencies. This finding supports prior studies indicating that nature-based interventions have therapeutic potential for promoting mental well-being6.

Interestingly, in the City Group state self-criticism fell significantly, but there was no significant change in state self-compassion. This partially support our hypotheses through reflecting the complexity of urban environments, which can act like a distractor and therefore due to that reduce self-criticism, but not foster self-compassion7,8,9. Urban environments have been linked to heightened stress and poorer emotional recovery36, which may explain why perceived stress significantly increased in the City Group. By contrast, the Forest Group exhibited no significant changes in perceived stress, which could be related to the stress typically associated with unfamiliar experiences, environments, and people8. As the intervention is new and one that people are unaccustomed to, the fact that there is no change in the level of stress in the forest virtual environment could be interpreted as a good result. One could assume that if the intervention had lasted longer, stress levels would have fallen as people became accustomed to it and benefited from being in the forest37.

Another consideration is the potential priming effect of completing the self-report measures, particularly the FSCRS (Gilbert et al., 2004), which explicitly asks participants to reflect on self-critical thoughts, feelings of inadequacy, and self-reassurance. Exposure to these items prior to the intervention may have inadvertently sensitized participants to their inner dialogue and fostered a form of implicit psychoeducation about self-criticism and its emotional impact. This effect could have contributed to reductions in self-criticism even in the absence of deep emotional engagement or immersive intervention, particularly in the urban setting where internal reflection might contrast sharply with external stimuli. Similar questionnaire-induced shifts have been noted in prior research, where measurement itself influenced participants’ self-awareness or emotional processing (McCambridge, Witton, & Elbourne, 2012). While this does not diminish the relevance of the findings, it underscores the importance of considering measurement effects when interpreting self-report outcomes in psychological intervention studies.

The stability of the self-protection and trait self-compassion and self-criticism scores across both groups indicates that short-term exposure to either virtual environment does not significantly influence interpersonal behaviours or deep-seated self-critical tendencies. This is consistent with findings from38 which highlight the trait-like stability of certain self-evaluative and interpersonal constructs over short intervention periods.

Regarding the non-significant findings on measures such as the FSCRS and s-SIB, while trait-level stability remains a plausible explanation (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998), we acknowledge that other factors may have contributed too. The brevity of the intervention and limited follow-up period may have constrained measurable change in more enduring self-related constructs (Kazdin, 2007). Moreover, technical limitations—such as occasional reductions in VR immersion due to overheating, signal dropout, or discomfort from head-mounted displays—may have weakened engagement and thus reduced the intervention’s emotional depth (Freeman et al., 2017; Wiederhold & Riva, 2019).

Regarding trait-level compassion and self-compassion, the lack of significant changes for self-compassion and compassion toward others across groups is consistent with the idea that deeply ingrained self-compassion traits require longer-term interventions for measurable change39. However, the significant decline in trait self-compassion toward others scores in the City Group is concerning and suggests that urban environments may have an adverse effect on compassion toward others. This finding is in line with research demonstrating that urban environments can suppress prosocial tendencies and empathy, potentially due to cognitive overload or reduced social connectivity40,41.

The observed decrease in compassion for others (SOCS-O) in the city group is also notable and requires further theorization. One plausible explanation is that immersion in a highly stimulating or socially dense urban environment may have activated self-protective threat responses, thereby downregulating affiliative systems related to compassion for others (Gilbert, 2010). According to evolutionary models of compassion, individuals may unconsciously prioritize self-focused regulation under perceived environmental threat, which can temporarily diminish outward social concern (Gilbert, 2005; Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010). It is also possible that the urban VR context disrupted feelings of social connectedness or increased interpersonal vigilance, both of which could reduce outward-directed compassion (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008).

Moreover, the study contributes to the conceptual development of forest bathing research by exploring its potential links to transdiagnostic psychological constructs such as self-compassion and self-criticism. Therefore, it suggests that nature-inspired VR experiences may hold promise as supportive tools for mental health and well-being, particularly in contexts where access to real natural environments is limited.

Future recommendations

It is also worth considering feedback from participants in the virtual reality interventions. During the pilot test, the urban environment was found to offer fewer sensory stimuli compared to the forest, a finding that was corroborated by participant testimonies: “After a while, I began to feel quite bored. It felt as though I was waiting for a bus that never arrived.” “The environment offered relatively few points of interest to explore within the given time frame, particularly from a seated position.” “Initially, I felt fully immersed in the world. The noise of the city was unsettling, and the presence of garbage and rats made me feel nauseous and uncomfortable.” Therefore, we recommend that the urban virtual environment should be adapted to include more stimuli. Future research could test the effectiveness of the revised virtual environments, with a bigger sample and shorter follow-up period of one month rather than two to address participant retention challenges. These adjustments could strengthen participant engagement and minimize data loss due to attrition over time. Future research should also explore the long-term effects of longer interventions and the underlying mechanisms behind these changes, incorporating both qualitative and physiological measures to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

Limitations

Several limitations of the study should be considered. The small sample limits the generalizability of the findings; future studies should include larger, more diverse populations42. The data collection room was not soundproofed and occasional external sounds from the university hall may have distracted participants. Technical issues with the virtual reality system, chest belt, and virtual reality applications disrupted the data collection on occasion. These included repeated dislocation of the virtual reality system settings, such as virtual space calibration and floor height, as well as problems with space and motion trackers and sensors, including signal dropout, automatic shutdowns, and tracker/sensor malfunctions. Additional challenges included overheating of the computer and headset, lagging of the virtual application, and difficulties with the calibration application for the virtual avatar. Signal dropout and unexpected problems with the chest strap, further contributed to the disruption. Moreover, the follow-up measurement may have been excessively long. Environmental factors such as high temperatures, made more unpleasant by use of the virtual reality headset, may have affected participant comfort and engagement. Finally, the cable was loose, and some participants complained that the headset was heavy, which may have negatively affected the overall experience.

Conclusion

The results of our pilot study, imply that a virtual forest environment can also increase the level of self-compassion as transdiagnostic factor for mental well-being and decreasing self-criticism, which is considered to be transdiagnostic factor of psychopathology38.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the ethical reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Clemente, D., Romano, L., Zamboni, E., Carrus, G. & Panno, A. Forest therapy using virtual reality in the older population: a systematic review. In Frontiers in psychology. Front. Media SA. 14, 8563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1323758 (2023).

Gao, T., Zhang, T., Zhu, L., Gao, Y. & Qiu, L. Exploring Psychophysiological restoration and individual preference in different environments based on virtual reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16, 3102 (2019).

Gentile, A., Bianco, A., Nordström, P. & Nordström, A. The stress reduction effect of nature through virtual reality (VR): a systematic review protocol. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-266331/v1.

Masters, R. et al. The impact of nature realism on the restorative quality of virtual reality forest bathing. ACM Trans. Appl. Percept. 22, 1–18 (2025).

Halim, I. et al. Individualized virtual reality for increasing Self-Compassion: evaluation study. JMIR Mental Health. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.2196/47617 (2023).

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P. & Daily, G. C. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1249 (1), 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x (2012).

Kaplan, R. & Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Ulrich, R. S. et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 11 (3), 201–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7 (1991).

Gilbert, P. An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. Int. J. Cogn. Therapy. 3 (2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.97 (2010).

Szitás, D., Halamová, J., Ottingerová, L. & Schroevers, M. The effects of forest bathing on self-criticism, self-compassion, and self-protection: a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 97, 102372 (2024).

McLaren-Gradinaru, M. et al. A novel training program to improve human Spatial orientation: preliminary findings. Front Hum. Neurosci 14, 147 (2020).

Bohil, C. J., Alicea, B. & Biocca, F. A. Virtual reality in neuroscience research and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 752–762 (2011).

The World Counts. World urban population. The World Counts. (2024). https://www.theworldcounts.com/populations/world/world-urban-population

Unity Technologies. Unity (Version 2022.1.0f1). Unity Technologies. https://unity.com/ (2022).

Valve Corporation. Steam (2003). https://store.steampowered.com/.

Halamová, J., Kanovský, M. & Pacúchová, M. Item-Response theory psychometric analysis and factor structure of the Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism scales. Swiss J. Psychol. 77, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000216 (2018).

Falconer, C. J., King, J. A. & Brewin, C. R. Demonstrating mood repair with a situation-based measure of self-compassion and self-criticism. Psychol. Psychother. 88, 351–365 (2015).

Ráczová, B., Hricová, M. & Lovašová, S. Overenie psychometrických vlastností slovenskej verzie dotazníka PSS-10 (Perceived Stress Scale) na súbore pomáhajúcich profesionálov. https://kramerius.lib.cas.cz/view/uuid:c2ebfea6-eea2-40cc-80b8-fc51f6c178e1?article=uuid:b85690df-db04-4247-9585-9ebe7a0effda.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A. Global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385 (1983).

Vráblová, V. & Halamová, J. Short version of the scale for interpersonal behavior: Slovak translation and psychometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 13, 14523 (2022).

Arrindell, W. A., Sanavio, E. & Sica, C. Introducing a short form version of the Scale for Interpersonal Behaviour (s-SIB) for use in Italy (2024).

Halamová, J. & Kanovský, M. Factor structure of the Sussex-Oxford compassion scales. Psihologijske Teme. 30, 489–508 (2021).

Gu, J. et al. Development and psychometric properties of the Sussex-Oxford compassion scales (SOCS). Assessment 27, 3–20 (2020).

Halamová, J., Kanovský, M. & Pacúchová, M. Robust psychometric analysis and factor structure of the forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring scale. Československá Psychologie. 61, 331–349 (2017).

Gilbert, P. et al. Criticizing and reassuring oneself: an exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 43, 31–50 (2004).

Francis, A. J. P. Nature Exposure Scale. unpublished work.

Wood, B. Smyth. The current and retrospective intentional nature exposure scales: development and factorial validity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16, 4443 (2019).

Szitás, D., Halamová, J. & Ottingerová, L. Slovak Adaptation of Nature Exposure Scale (Unpublished manuscript). Institute of Applied Psychology, Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences (Comenius University in Bratislava, 2024).

Slater, M. & Usoh, M. R. Systems perceptual position, and presence in immersive virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2, 221–233 (1993).

Regenbrecht, H. & Schubert, T. Real and illusory interactions enhance presence in virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 11, 425–434 (2002).

Schubert, T., Friedmann, F. & Regenbrecht, H. The experience of presence: factor analytic insights. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 10, 266–281 (2001).

Schubert, T. W. The sense of presence in virtual environments: a three-component scale measuring Spatial presence, involvement, and realness. Z. Medienpsychol. 15, 69–71 (2003).

Jamovi Team. Jamovi (Version 2.6.19). (2024). https://www.jamovi.org.

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L. & Steindl, S. R. A Meta-Analysis of Compassion-Based interventions: current state of knowledge and future directions. Behav. Ther. 48, 778–792 (2017).

Neff, K. Self-Compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2, 85–101 (2003).

Ellis, C. The new urbanism: critiques and rebuttals. J. Urban Des. 7, 261–291 (2002).

Franco, L. S., Shanahan, D. F. & Fuller, R. A. A review of the benefits of nature experiences: more than Meets the eye. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14, 864 (2017).

Zessin, U., Dickhäuser, O. & Garbade, S. The relationship between Self-Compassion and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being. 7, 340–364 (2015).

Neff, K. & Germer, C. A. Pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful Self-Compassion program. J. Clin. Psychol. 69, 28–44 (2013).

Kuo, M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 6, 1452 (2015).

Sandstrom, G. M. & Dunn, E. W. Social interactions and Well-Being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 40, 910–922 (2014).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112, 155–159 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Oliver Chrkavý, Andrea Lukač, Nataša Paľovčíková, and Emma Prišticová, for help with data gathering. We are grateful for programming the intervention to Yulian Rusyn and his supervisor Zuzana Berger Haladová from Department of Applied Informatics, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics, and Informatics at Comenius University Bratislava.

Funding

This work is supported by the Vedecká grantová agentúra (Slovak Science Grant Agency) VEGA under Grant 1/0054/24. Funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V04-00258.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS and JH designed the research, wrote the article, interpreted the results, revised the manuscript. VP helped with the forest environment selection. DS performed the statistical analysis. All authors revised, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study’s protocol was approved by the Ethical committee of the Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences at Comenius University Bratislava FSEV 1647/-4/2022/SD-CIII/1.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szitás, D., Halamová, J. & Pichler, V. Virtual exposure to natural versus urban environments: a pilot study on impacts on self-compassion, self-protection, and self-criticism. Sci Rep 15, 29963 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15009-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15009-5