Abstract

Triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS) are recently widely employed in thermal engineering applications due to their smooth surfaces, high surface area to volume ratio and mathematically controlled geometry features. Although the sheet-type TPMS shows good heat transfer capacity between the fluid and the skeleton surface, the pressure drop of this structure is large resulting from its partially disconnected surface. In this paper, four TPMS structures, sheet Gyroid, solid Gyroid, solid Primitive and solid Diamond were designed and manufactured by 3D printing technology. The heat transfer performance of different TPMS structures and the fin structure was researched by means of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and experimental methods. The results showed that the heat dissipation capability of the fin structure was better than that of the TPMS structures under ultra-low speed airflow. Otherwise, the heat transfer performance of the solid TPMS is better than both of the sheet TPMS and the fins structures. Although the sheet TPMS has higher surface area compared to the solid TPMS, the flow speed was decreased along the internal channels leading to greater thermal resistance and lower thermal transferring efficiency. When the gas velocity was less than 4 m/s, the solid Gyroid expressed the best performance among the three solid TPMS structures caused by its higher surface area connected to the heat source. Under higher gas velocity, the solid Diamond was proved to have better performance led by higher flow speed within channels. The heat transfer coefficient of solid Diamond was 110% and 59% larger than that of the solid Primitive and the solid Gyroid, respectively. The Nusselt number of solid Diamond was 10% and 12% greater than that of the solid Primitive and the solid Gyroid, respectively. The research proves that the solid TPMS can be used to replace the fin structure in heat exchangers and provides a basis for design and optimization of TPMS-based heat exchangers in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increased level of miniaturization and integration of electronic devices, there is high-power thermal energy generation per unit volume1. Effective heat exchangers could guarantee normal work of electronic devices especially for high-power heat loads such as automotive vehicles, aerospace, nuclear power, defense electronics and chemical industries. It is important to improve the heat exchange rate and reduce the dimensions and cost of heat exchangers2,3. Various types of heat exchangers are available such as the shell and tube heat exchangers, plate fin heat exchangers, fin and tube heat exchangers etc4.

Shell and tube heat transfer systems are the most widely used types in high-pressure industrial and commercial fields5. To promote efficiency, geometrical parameters are optimized including changing the appearance of the heat exchanger, adding more inserts in the tube and redesigning the baffles on the shell side6. Plate fin heat exchangers have been extensively used in the commercial genre of heat exchangers because of their compactness, flexibility, maintainability, greater surface area to volume ratio and greater heat transfer performance compared to the shell and tube heat exchangers7. Various kinds of inserts have been employed in the heat exchangers8, such as plate fins9,10,11, interleaved fins12, cylindrical fins13,14 and needle fins15,16. Besides, the shape and size of the flow path and the obstructions significantly affect the heat exchange performance17. Corrugated or modified surface can effectively increase the heat transfer area and improve flow turbulence, but it can also induce intricate fluid flow due to formation of swirling patterns and recirculation zones18.

Owing to mechanical limits, the conventional commercially manufactured heat exchangers have obstructions when it comes to microscale19. Thanks to the recent revolution in additive manufacturing (AM) technology, heat exchangers with complex geometric structures can now be efficiently fabricated, overcoming traditional manufacturing limitations. Triple periodic minimal surface (TPMS) heat exchanger is a new type of heat exchanger that can be quickly designed by mathematical equations and manufactured by AM technologies20. Learning from the architectures of biological tissue, beetle scales, butterfly wings and shells21,22,23, the 3D periodic structure with entangled surfaces and locally minimized surface area of zero mean curvature express superior physical characteristics24. Moreover, TPMS structures are featured by their smooth surface, highly interconnected porous structure and mathematically controllable geometrical features25. Benefiting from its structure, TPMS is currently widely used in thermal management devices.

The most commonly used TPMS structures include the Diamond, the Primitive and the Gyroid structures26. Baobaid et al.27 tested the competence of heat exchangers designed using seven TPMS structures to transfer heat. The findings indicated that heat exchangers using TPMS structures were 48–61% more effective in heat transfer than conventional ones. Attarzadeh et al.28 analyzed the interdependence among gas flow velocity, heat exchange and thermal capacity concerning the walls of varying thickness designed using the Diamond structure and reported that the ability of the heat exchange was significantly affected by the variation in wall thickness. Jaisree et al.29 compared the heat transfer capacity of TPMS to that of another porous structure PNS, and observed that Diamond structure displayed superior heat exchange performance with notably smaller volume. Thomas et al.30 analyzed spacer strips fabricated using five different TPMS structures and used mesh-type spacers in membrane distillation. The findings indicated that a 63% improvement in the overall heat transfer coefficient of the film was observed for the structures based on TPMS in contrast to conventional structures.

It is noteworthy that the TPMS structures can be categorized into sheet TPMS and solid TPMS structures by thickening the minimal surface. At present, the research mainly focuses on the sheet TPMS. The sheet TPMS exhibit higher surface area to volume ratio compared to their solid counterparts at a unit cell size31. Although the sheet TPMS is found to have superior thermal performance as a result of their larger surface, it exhibits greater pressure drop compared to the solid TPMS32. The natural convection heat transfer properties of enriched types of TPMS structures need to be investigated under forced convection heat exchangers, which is the goal of this study.

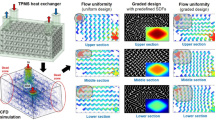

To solve the above problems, this paper explores the flow and heat transfer mechanism of four TPMS structures including the sheet Gyroid, solid Gyroid, solid Primitive and solid Diamond. The porous TPMS heat exchangers were designed and manufactured by 3D printing technology. The heat transfer performance of different TPMS structures and the fin structure was researched by means of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and experimental methods. The pressure drop and friction coefficient of the air flow were evaluated to determine the air flow characteristics. The thermal performance of the structures was explored by evaluating the convection heat transfer coefficient (h), Nusselt number (Nu) and convection heat transfer quantity (Q). All of the computational results were further verified through experimental tests.

Methods

Mathematical design of TPMS structures

Primitive, Gyroid and Diamond surfaces can be described by the following equations given in Table 1. The function f(x, y, z) is and iso-surface evaluated at an iso-value C. The space is separated by the TPMS surface as two parts when the equation f(x, y, z) < C and f(x, y, z) > C. In these equations, l adjusts the period of the unit in x, y and z directions and c determines the relative densities. By offsetting the minimal surface along its normal direction and against the normal direction by solving the equation –C ≤ f(x, y, z) ≤ C, a double surface can be created. The spatial nodes bounded by these two double surfaces then construct the sheet TPMS structure (Fig. 1a). On the contrary, by solving the equation f(x, y, z) < C and f(x, y, z) > C, solid TPMS structures can be generated where one of the two spaces separated by the minimal face are solidified. In this work the Gyroid TPMS is designed to both sheet and solid type, while the Primitive and the Diamond TPMS are utilized as a solid type (Fig. 1b, c and d).

TPMS structures, TPMS unit cell and fabricated TPMS structures. (a) Sheet-type Gyroid structure, (b) Solid-type Gyroid, (c) Solid-type Primitive, (d) Solid-type Diamond, (e) fabricated TPMS structures (Top view), (f) fabricated TPMS structures (Front view). (By Adobe Photoshop (26.0.0) drawn, visit website: https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html).

On the basis of the above equations, the modeling process was conducted using Wolfram Mathematica 11.0 software. The three dimensional models were generated using the RegionPlot3D function. TPMS structures with different morphologies were designed. The parameters were exhibited in Table 2, where Area represents the surface area, and A denotes the wetted area, which is the contact area with the fluid, also known as the heat transfer area required to calculate the hydraulic diameter. Then these models were exported as STL files for further additive manufacturing and numerical analyses.

Materials and manufacturing

In this study, Ti-6Al-4 V powder (15–53 μm) was used as the raw material for printing TPMS structures, the O, N, H, C, Fe and other trace elements in Ti-6Al-4 V powder are low, which conforms to ASTM F136-02a standard. In addition, Ti-6Al-4 V powder can eliminate residual stress in porous structures. The TPMS structures were manufactured using L-PBF equipment. Using additive manufacturing technology for printing porous structures, L-PBF technology can increase printing accuracy. The main process parameters of L-PBF equipment include laser power, scanning speed and layer height. When printing the TPMS porous structure sample, the parameters set were shown in Table 3.

Due to the inherent limitations of the L-PBF process, manufacturing tolerances were considered. For the dimensions of the cuboid samples, a tolerance of ± 0.15 mm was applied. This tolerance was determined based on established L-PBF manufacturing standards. Furthermore, the surface finish of L-PBF fabricated parts is known to be inherently rough. To mitigate the potential impact of surface roughness on experimental results, several measures were taken. The L-PBF process parameters were optimized to minimize surface roughness. A layer thickness of 30 μm, a laser power of 200 W, and a scan speed of 800 mm/s were employed. These parameters were selected based on prior research and optimization studies to achieve a balance between part density and surface finish. considering the scale of our experiment, where the characteristic length (25 mm cube edge) is significantly larger than the expected average surface roughness (on the order of micrometers), the relative roughness (ratio of roughness height to characteristic length) is very small. This implies that the additional pressure drop and boundary layer modifications due to surface roughness would be negligible compared to the overall system behavior. Therefore the surface roughness, at the expected level, has a minimal impact on the overall experimental results.

Governing equation of the mathematical model

The TPMS 3D models were imported into COMSOL Multiphysics 5.5 software for finite element analysis under multi-physical phenomena coupling environment and verified the accuracy of simulation results through experiments.

The underlying theory of the finite element method is the principle of minimum potential energy and the principle of minimum complementary energy. The method relies on using several regular shaped continuous sub-domains known as “grid cells” to approximately represent the whole solution domain. The physical quantities at the vertices of these cells can accurately satisfy the original governing equations. The governing equations in COSMOL are always converted into a weak form first, followed by construction of a set of finite element equations used for calculation.

Conservation of mass, momentum, and energy govern fluid flow and heat transfer. The physical laws equations for fluid flow are as presented below.

The equation on conservation of mass:

The equation shows that the increase in mass in is equal to the mass acting on the governing body.

The equation on conservation of momentum:

This equation indicates that the increase in momentum in the governing body is equal to the momentum acting on the governing body plus the impulse acting on the surface of the governing body and the impulse of the volume force on the governing body .

Equation on conservation of energy:

This equation indicates that the change in energy within the governing body is equal to the energy flowing into the governing body Ω plus the effect of the forces on the surface of the governing body plus the effect of the volume forces plus the heat flowing into the control body.

In this study, the thermal conductivity of the material used to fabricate the TPMS structure (Ti-6Al-4 V) is 7.955 W/m·K, significantly higher than that of air (0.0258 W/m·K). This substantial difference promotes efficient heat transfer between the solid structure and the surrounding fluid, leading to a minimal local temperature difference between the phases. Furthermore, according to the Stefan-Boltzmann law, radiative heat flux is negligible under the low temperature difference conditions relevant to this work. Therefore, the radiation effect can be excluded and assume local thermal equilibrium in this study. The heat transfer equation describing the average temperature of a solid and fluid in the case of local thermal equilibrium can be expressed as:

In this study, the laminar flow model for single-phase flow was used to manage the thermal dissipation issue in TPMS. The assumption of the sliding wall boundary condition in a single-phase flow physical field interface is that the speed of the fluid tangential to the wall is equal to that of the wall. This means that there is no effect of boundary layer disturbance, and the mathematical expression is presented as shown below:

At the macroscopic scale, the relationship between u(m/s) and p(Pa) is:

where µ denotes the fluid’s viscosity and the permeability κ is calculated using the formula:

where the porosity ε is the proportion of the pore volume to the total volume, as expressed in Eq. (10) and the equivalent pore diameter dp can be written as Eq. (11)33.

CFD modeling and boundary conditions

A common heat exchanger comprises two fin types: outer fin and inner fin. In this study, the wall in contact with the hot fluid represented the solid heat source (Fig. 2). The conventional fins used to increase heat transfer were replaced with TPMS (50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm). The TPMS was placed in an area slightly larger than itself (51 mm × 51 mm × 51 mm). Air was used as a coolant, flowing in from the inlet through the TPMS and then out of the outlet. The boundary conditions can be seen in Fig. 2. The wall of the channel was adiabatic except for the entrance and the exit. The bottom was in contact with a heating source producing one joule per second of heat energy.

Illustration of the heat changer modeling process and finite element analysis. (By Adobe Photoshop (26.0.0) drawn, visit website: https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html)

A rectangle slightly larger than the TPMS was used to surround the TPMS in COSMOL, which served as a channel for the air to flow through the system. A rectangular sheet was employed as a heat producer located at the bottom of the TPMS. A joint was formed and the boundary conditions were set. The computational domain was meshed and solved with the laminar steady state solver in conjugate heat transfer. A mesh independence study was conducted by incrementally refining the grid from 1.2 to 4.5 million elements. Heat source temperature and pressure drop varied by less than 1.5% between 3.2 and 4.5 million elements, confirming mesh adequacy. Final simulations used 3.2 million tetrahedral elements with three boundary layers (total thickness 0.1 mm) to resolve near-wall gradients. The characteristics of all materials used in the model are depicted in Table 4. Aluminum was used as a reference material for comparative analysis of the specific thermal properties of Ti-6Al-4 V TPMS.

Post-processing of results

The characteristic of each structure were analyzed using the Reynolds number Re and friction coefficient f. Re was expressed as:

where ρ represents fluid mass density, v is the fluid’s speed in the flow direction, dh represents the hydraulic diameter, and µ denotes the fluid’s viscosity. The hydraulic diameter was four times the ratio of the area of the inlet through which the fluid was flowing through the section to the circumference, expressed as: dh=4A/c, where A represents the cross section area and c denotes the wetted circumference. The cross section area and wetted circumference of a TPMS structure can vary throughout its length, thus the hydraulic diameter in this study was defined based on the volume and surface area29 expressed as dh=4V/AS, where V stands for the volume, while the wetted area is denoted by AS in this expression28.

The fan friction factor (f) is commonly used to compare pressure loss in channels, and it can be expressed as shown below:

where ΔP represents the pressure decrease through the channel, ΔL denotes the characteristic length and U represents the speed.

The performance of heat exchange was measured using the heat transfer coefficient h and the Nusselt number Nu was utilized to determine the proportion of convection heat transfer to total heat transfer. The following equations were employed to compute the heat transfer coefficient and Nusselt number.

where Qy denotes the difference in heat between the input and output segments, A represents the contact area, Tα is used to represent the mean surface temperature, whereas T∞ refers to the temperature of the wall. In the second equation, dh denotes the hydraulic diameter and κ represents the fluid’s heat conductivity coefficient.

Results and discussion

The heat exchange capacity of the fins and that of the sheet and the solid Gyroid structures were first compared. Then the heat exchange capacities of the three solid TPMS configurations, i.e., the Primitive, Gyroid and Diamond, were further analyzed.

Air flow and heat transfer characteristics of fins and gyroid TPMS

The fins have the same dimensions as the TPMS heat exchangers and the enclosure for all models has the same size. The temperature of the heat source was the lowest for the fins compared with the Gyroid when the inlet air velocity was low. The temperature of the heat source for the Gyroid structure was lower than the fins at high air velocity. The rate of decrease in temperature was maximum under the solid Gyroid structure. The heat transfer efficiency of the solid Gyroid structure was 21% superior to that of the fins (Fig. 3a).

The interface region where the air comes into contact with the heat source through the fins was 1.35 and 1.92 times larger than the sheet Gyroid and solid Gyroid structures, respectively. This finding indicates that the fins exhibited the highest heat dissipation efficiency when the inlet velocity was low. However, the internal structure of Gyroid is compact and designed to decrease flow resistance, therefore as the inlet velocity gradually increased, the fluid velocity was also faster in the Gyroid structure compared with the fins. As a result, the boundary layer of the Gyroid structure was thinner than the that of the fins. The findings revealed that the air velocity along the surface showed a slight increase due to the abundance of cavities and openings internally in the fin-based heat exchanger. On the contrary, the velocity of fluid in the Gyroid structure was significantly high due to the compact internal structure. The highest air flow velocity was observed along the inside of the channel in solid Gyroid structure. The solid Gyroid exhibited air flow rates 1.31 and 1.93 times higher than those of the sheet Gyroid and fins, respectively. This indicates that the Gyroid architecture exhibited the least hydrodynamic drag and the greatest flow rate within the channel.

The streamline illustrations of the sheet and solid Gyroid structures are demonstrated in Fig. 3b. The results validated that the fluid spread across the whole surface of the sheet Gyroid structure through its internal small channels (presented as channel 2 in Fig. 3b). The findings indicate that the air velocity reduced but the surface area was larger. The streamline illustration showed that the flow was discontinuous, resulting in thicker thermal boundary layer, which reduced the effectiveness of thermal energy exchange. The air flow speed in the Gyroid structure only increased within channel 1 (Fig. 3b). As a result, the solid structure type showed a better thermal conduction efficiency than the sheet type.

Analysis of heat transfer and fluid flow in fins and Gyroid structures. (a) The effect of temperature on inlet velocity, (b) A representation of the fluid flow in Gyroid structures in the form of sheets and solids(By Adobe Photoshop (26.0.0) drawn, visit website: https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html).

Heat transfer performance of the solid TPMS structures

For all the TPMS structures, there was a linear increase in the Reynolds number Re as the inlet velocity increased. The Diamond structure exhibited the lowest rate in increase in Re owing to smallest length scale.

The heat source temperature decreased rapidly for all TPMS structures as the inlet velocity increased (Fig. 4a). Heat conduction through solid TPMS structures was mainly dependent on the thermal conduction between the TPMS structure and heat source. The touching area between the Gyroid structure and the heat source was 1023 mm2, whereas the Diamond structure exhibited a contact area of 701 mm2. This implies that the thermal conductivity effectiveness of the Gyroid architecture was better than that of the Diamond structure for small inlet velocity. The Primitive structure had the worst heat transfer efficiency compared with the remaining two TPMS structures. The heat source temperature for the Diamond structure became the lowest when the inlet velocity increased due to its more compact structure, which was beneficial for forced convection and created a more stable and continuous flow. The heat source temperature was close to the air inlet temperature for all TPMS structures when the inlet velocity increased to a certain level.

For all TPMS structures, an elevation in Reynolds number resulted in a rise in pressure loss (Fig. 4b). The pressure reduction of Diamond structure was two-fold that of the Primitive structure. Because the sum of kinetic and pressure energy is constant under steady flow, thus a smaller increase in kinetic energy corresponds to a smaller decrease in pressure energy, leading to smaller pressure drop. Therefore, the Primitive structure exhibited the lowest pump consumption and needed the least amount of energy to convey the fluid. However, The TPMS structures failed to show a similar decreasing trend of the friction coefficient against the increase in the Reynolds number (Fig. 4c). At low Reynolds numbers, the friction coefficient of Primitive is the highest, while the friction coefficient of Diamond is the lowest. This is due to the fact that Primitive has larger and continuous channels, while Diamond’s channel is more complex. Therefore, at the same Reynolds number, the pressure drop of Primitive is lower than that of Diamond. However, due to the larger hydraulic diameter of Primitive, it results in a higher friction coefficient.

Analysis of heat transfer capability of TPMS

The temperature gradients of all structures moved from blurred to clear when the Reynolds number experienced a transition from 50 to 300, which can be attributed to the overall temperature difference. The temperature gradient of Diamond was smaller than that of the Primitive and Gyroid structures at the same Reynolds number, indicating that the Diamond structure was more efficient in heat transfer (Fig. 5).

The change in Reynolds numbers was consistent with the trend of the heat transfer coefficients (Fig. 6a). The heat transfer coefficients gradually increased as the Reynolds number increased between the range of 50 to 300. The heat transfer coefficients were highest for the Diamond structure compared with the other structures. The heat transfer coefficient of Diamond was 210% of that of the Primitive structure and 159% of Gyroid structure when the Re is 300. The Nu value was highest for Diamond followed by Primitive and Gyroid (Fig. 6b). The Nu value for the Primitive and Gyroid structures were closer and the three structures had closer values at relatively lower Re. The Nu value for the Diamond structure was 1.10 and 1.12 times greater than that of the Primitive and Gyroid structures. This observation can be credited to the efficiency of convective heat transfer. The Nu value for the Primitive structure was greater than that of the Gyroid when Re > 150. This trend can be attributed to the stability of flow in the Primitive structure at high Re due to its simple internal structure.

Experimental verification

The printed TPMS structural model has dimensions of 25 mm × 25 mm × 25 mm, representing 12.5% of the dimensions in the simulation. The experimental sample was scaled down to match fabrication constraints, while maintaining geometric similarity. High-resolution micro-computed tomography (µ-CT) was employed to scrutinize the as-printed morphology and quantify manufacturing fidelity (Fig. 7a–f). Subsequent image analysis revealed a high degree of geometric precision; the deviation between the measured and designed porosity was quantified, yielding an average relative error of merely 3.21% (Fig. 7g). This low error margin confirms the robustness of our fabrication protocol in accurately replicating the complex topology of the TPMS design.

Characterization and fidelity of fabricated TPMS structures. (a–c), Pho-tographs of printed samples: (a) Primitive, (b) Gyroid, and (c) Diamond. (d–f), Corresponding µ-CT cross-sections visualizing the internal morphology. (g) Co-mparison of designed versus measured porosity, quantified from µ-CT scans. (By Adobe Photoshop (26.0.0) drawn, visit website: https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html).

Non-dimensional parameters (Re, Nu) were preserved between simulations and experiments for TPMS structures. This ensures comparable flow and heat transfer behavior27. Sheet-type Gyroid was excluded from experiments due to its high pressure drop (as shown in simulations) and structural fragility during L-PBF fabrication. Future studies will optimize its manufacturability. The experimental setup is placed as shown in Fig. 8. A fan is served as the air source, the gas velocity is adjusted by a regulating valve connected to the fan to achieve the desired gas velocity and a shape converter is used to create a rectangular channel. The heat source consists of a copper piece connected to a DC regulated power supply, with a metal piece resistance of 0.1 Ω. The DC regulated power supply is regulated to maintain a current of approximately 3.3 A through the copper piece, ensuring a stable power of 1 W. The resulting heat flux was selected, in part, due to the small size of the TPMS structures under investigation. Furthermore, the primary aim of this study was a focused comparative analysis of the relative thermal performance across different TPMS configurations under identical boundary conditions. A limitation of this approach, however, is that it restricts the direct applicability of the findings to higher-power scenarios. Therefore, future work will examine performance at heat fluxes relevant to electronics cooling applications, including measurements of pressure drop and detailed temperature mapping, to more fully assess the potential of these TPMS structures. The copper piece is placed on a insulating board to minimize heat exchange with the surrounding environment, ensuring more accurate experimental results. The TPMS model is positioned on the copper piece and surrounded by heat-insulating material, placing it within a rectangular channel. When the TPMS structure was replaced in the middle of the experiment, the heat was preheated for 10 min first, and then the average temperature of the heat source for the next 10 min was recorded with the SMD thermocouple.

Among the three sets of experimental data, when fluid flow is undisturbed, the Gyroid structure exhibits the best heat dissipation performance, this result is consistent with the simulation result. When flow perturbations (e.g., pulsation, turbulence) introduced via the regulating valve (these conditions were simulated using transient velocity profiles (0.5–2 Hz fluctuations) at the inlet boundary) the data from Fig. 8b and c suggest that at higher fluid velocities, around 4 m/s, the heat dissipation effectiveness of the Diamond structure surpasses that of the Gyroid structure. This observation is also consistent with the corresponding simulation results. In the simulations, the Primitive structure consistently exhibits lower heat dissipation performance compared to the Gyroid and Diamond structures. However, due to non-ideal experimental conditions, factors such as fluctuating environmental temperature, inconsistencies in the size of sample, surface smoothness, varying electrical currents, and non-standardized procedures introduce errors in the obtained results under the same conditions. To mitigate these concerns, we employed a high-precision current source (accuracy within ± 0.1%) to minimize current variations, and sample dimensions were meticulously measured using digital calipers, where observed variations (within ± 0.05 mm) contributed a maximum of ± 1.5% uncertainty to the calculated results. Furthermore, temperature measurements were performed using surface-mount device (SMD) thermocouples, which were calibrated to an accuracy of ± 0.1 °C, contributing a relative error of approximately ± 1.2% to the determination of ΔT. Ambient heat loss was rigorously estimated via comprehensive insulation testing, demonstrating a heat loss of less than 2% of the total input power, and this was subsequently incorporated as a systematic error of ± 0.5 °C in our calculations. A thorough propagation analysis, utilizing the root-sum-square methodology, yielded a combined standard uncertainty for ΔT of ± 1.8 °C (at a 95% confidence interval), thereby providing a robust quantification of the experimental precision, particularly critical given the small ΔT values encountered in this study. In Fig. 8a, the Primitive structure demonstrates the highest heat dissipation capability. This discrepancy may be attributed to the non-ideal smoothness of the structural surfaces, the increased complexity of real flow conditions compared to simulated environments, non-standardized operations, measurement errors, and other contributing factors, leading to this experimental outcome. While both simulations and experiments show heat transfer enhancement with increasing velocity (Figs. 4a and 9), discrepancies arise for the Primitive structure. Experimentally, its performance deviates due to surface roughness (Ra = 15 μm) and airflow bypass effects caused by minor geometric distortions (± 0.3 mm). In order to quantify and statistic the error between simulation and experiment, statistical analysis was carried out through the ratio between the temperature drop ratio and the gas flow rate. The average value of the three groups of experiments in Fig. 8 was compared with the results in Fig. 4a, and the error was 9.258 ± 3.247%.

Beyond the analysis of temperature drop uncertainties, we have also characterized the key dimensionless flow parameters, Re and Nu. These parameters were derived from indirect measurements of fundamental experimental variables. A quantitative comparison of these experimentally derived Re and Nu values against CFD simulations, along with an associated error analysis highlighting the percentage deviations, is presented in Table 5. This allows for a comprehensive assessment of the agreement between our experimental findings and the numerical model for critical flow and heat transfer characteristics.

Conclusions

In this research, the thermal performance of solid TPMS were investigated and compared with the efficiency of fins and sheet TPMS. The results obtained through numerical models were verified by experiments. The results indicate that solid TPMS structure has better thermal performance than the conventional fins and sheet TPMS under high gas velocity. The friction factor was lowest in the Primitive structure owing to the simple geometric shape. The Gyroid structure with larger contact area to the heat source exhibited the best heat transferring effect under low gas velocity (about < 4 m/s). The Diamond structure had the highest heat transfer coefficient under high gas velocity. However, Although the present study provides a comprehensive analysis of the thermal performance, the experimental data have not been utilized to compute the Nusselt number and heat transfer coefficient for direct comparison with the simulations. Future work will focus on incorporating these metrics to enhance the completeness of the study and further validate the numerical results.Studies should be conducted to explore the correlation between the heat exchange efficiency and the porosity of the TPMS structures. These findings provide information for the development of heat exchanger equipment based on TPMS structures.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- u :

-

x component of velocity [m/s]

- v :

-

y component of velocity [m/s]

- w :

-

z component of velocity [m/s]

- U :

-

Velocity of the gas [m/s]

- ρ :

-

Density [kg/m3]

- v :

-

Kinematic viscosity [kg/ms]

- µ :

-

Dynamic viscosity [m2/s]

- P :

-

Pressure [kPa]

- m :

-

Quality [kg]

- n :

-

Normal vector

- F :

-

Body force [N]

- E :

-

Internal energy [J]

- τ :

-

Stress tensor [N/m]

- C P :

-

Specific heat capacity [J/kg K]

- T :

-

Temperature [K]

- κ :

-

Thermal conductivity [W/m K]

- V :

-

Volume [m3]

- d h :

-

Characteristics length or Hydraulic diameter [m]

- h :

-

Convective heat transfer coefficient [W/m2 K]

- A tot :

-

Total area[m2]

- A :

-

Contact area

- T α :

-

Average surface temperature

- T ∞ :

-

Wall temperature

- Re :

-

Reynolds number [–]

- Nu :

-

Nusselt number [–]

References

Zhang, X., Wu, S., Zhang, C. & Chen, Y. Dynamic heat transfer characteristics of gravity heat pipe with heat storage. J. Energy Storage. 53, 105134 (2022).

Patel, B. V., Sarviya, R. & Rajput, S. Numerical investigations for the performance improvement of a tubular heat exchanger with anti-clockwise clockwise twisted tape inserts. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 44 (2), 4381–4397 (2022).

Carpio, J. & Valencia, A. Heat transfer enhancement through longitudinal vortex generators in compact heat exchangers with flat tubes. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 120, 105035 (2021).

Rao, R. V., Saroj, A., Oclon, P. & Taler, J. Design optimization of heat exchangers with advanced optimization techniques: A review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 27 (2), 517–548 (2020).

Lu, D., Wang, Y. & Yuan, B. Porous media algorithm for thermal-hydraulic numerical simulation of shell and tube heat exchanger. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 54 (3), 429 (2020).

Lin, W., Cao, J., Fang, X. & Zhang, Z. Research progress of heat transfer enhancement of shell-and-tube heat exchanger. Chem. Ind. Eng. Progress. 37 (4), 1276–1286 (2018).

Li, K., Wen, J. & Wang, S. Effect of axial heat conduction on heat transfer performance of plate fin heat exchanger under different thermal boundary condition. CIESC J. 72 (4), 1956–1964 (2021).

Ao, C., Yan, S., Hu, W., Zhao, L. & Wu, Y. Heat transfer analysis of a PCM in shell-and-tube thermal energy storage unit with different V-shaped fin structures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 216, 119079 (2022).

Haghighi, S. S., Goshayeshi, H. & Safaei, M. R. Natural convection heat transfer enhancement in new designs of plate-fin based heat sinks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 125, 640–647 (2018).

Lei, X., Lin, Z., Wang, Y., Li, X. & Liu, Y. Numerical investigation of condensation characteristics of a moist air-to-air plate-fin heat exchanger and experimental validation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 191, 122846 (2022).

Allahyarzadeh-Bidgoli, A., Mehrpooya, M. & Yanagihara, J. I. Geometric optimization of thermo-hydraulic performance of multistream plate fin heat exchangers in two-stage condensation cycle: thermodynamic and operating cost analyses. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 162, 631–648 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Peng, J., Yang, R., Yuan, L. & Li, S. Weight and performance optimization of rectangular staggered fins heat exchangers for miniaturized hydraulic power units using genetic algorithm. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 28, 101605 (2021).

Yang, A., Chen, L., Xie, Z., Feng, H. & Sun, F. Constructal operation cost minimization for in-line cylindrical pin-fin heat sinks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 129, 562–568 (2019).

Kore, S. S., Yadav, R., Chinchanikar, S., Tipole, P. & Dhole, V. Experimental investigations of conical perforations on the thermal performance of cylindrical pin fin heat sink. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43 (1), 3431–3442 (2022).

Markal, B., Kul, B., Avci, M. & Varol, R. Effect of gradually expanding flow passages on flow boiling of micro pin fin heat sinks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 197, 123355 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Topological Studies on Arrays of the Manifold Micro-Pin-Fin Heat Sinks, Available at SSRN 4174800.

Baïri, A. Water–Copper nanofluid free convective heat transfer between concentric cones. Heat Transf. Eng. 44 (1), 57–64 (2023).

Rabby, M. I. I. & Uddin, M. W. Convection heat transfer augmentation inside a hybrid corrugated channel by varying the positions of corrugated configurations. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 52 (2023).

Niknam, S. A., Mortazavi, M. & Li, D. Additively manufactured heat exchangers: a review on opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 112, 601–618 (2021).

Jihong, Z. et al. A review of topology optimization for additive manufacturing: status and challenges. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 34 (1), 91–110 (2021).

Guo, X. F., Zheng, X. Y., Yang, Y., Yang, X. Y. & Yi, Y. Mechanical behavior of TPMS-based scaffolds: a comparison between minimal surfaces and their lattice structures. SN Appl. Sci., 1(10) (2019).

Fu, J. J. et al. Design and mechanical characterization of an S-Based TPMS Hollow isotropic cellular structure. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 131 (2), 695–713 (2022).

Kapfer, S. C., Hyde, S. T., Mecke, K., Arns, C. H. & Schröder-Turk, G. E. J. B. Minimal Surf. Scaffold Designs Tissue Eng. 32(29) 6875–6882. (2011).

Sychov, M. M., Lebedev, L. A., Dyachenko, S. V. & Nefedova, L. A. Mechanical properties of energy-absorbing structures with triply periodic minimal surface topology. Acta Astronaut. 150, 81–84 (2018).

Feng, J., Fu, J., Yao, X. & He, Y. Triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) porous structures: from multi-scale design, precise additive manufacturing to multidisciplinary applications. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 4 (2), 022001 (2022).

Cheng, Z., Xu, R. & Jiang, P. X. Morphology, flow and heat transfer in triply periodic minimal surface based porous structures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 170, 120902 (2021).

Baobaid, N., Ali, M. I., Khan, K. A. & Al-Rub, R. K. A. Fluid flow and heat transfer of porous TPMS architected heat sinks in free convection environment. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 33, 101944 (2022).

Attarzadeh, R., Rovira, M. & Duwig, C. Design analysis of the Schwartz D based heat exchanger: A numerical study. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 177, 121415 (2021).

Iyer, J., Moore, T., Nguyen, D., Roy, P. & Stolaroff, J. Heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics of heat exchangers based on triply periodic minimal and periodic nodal surfaces. Appl. Therm. Eng. 209, 118192 (2022).

Thomas, N., Sreedhar, N., Al-Ketan, O., Rowshan, R. & Al-Rub, R. K. A. Arafat, 3D printed triply periodic minimal surfaces as spacers for enhanced heat and mass transfer in membrane distillation. Desalination. 443, 256–271 (2018).

Al-Ketan, O., Rowshan, R. & Abu Al-Rub, R. K. Topology-mechanical property relationship of 3D printed strut, skeletal, and sheet based periodic metallic cellular materials. Addit. Manuf. 19, 167–183 (2018).

Yan, G. H. et al. Simulation and experimental study on flow and heat transfer performance of sheet-network and solid-network disturbance structures based on triply periodic minimal surface. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 219 (2024).

Cheng, Z., Li, X., Xu, R. & Jiang, P. Investigations on porous media customized by triply periodic minimal surface: heat transfer correlations and strength performance. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 129, 105713 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171358, 52005268), the Open Research Fund of Guangdong Key Laboratory of Minimally Invasive Surgical Instruments and Manufacturing Technology, Guangdong University of Technology (MISIMT-2021-5), the Natural Science Fund for Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province (20KJA460004) and the Graduate Research and Innovation Projects of Jiangsu Province (KYCX22_1621).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.: Methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft, X.W.: Software, validation, writing-original draft, H.L.: Methodology, formal analysis, J.S.: Data curation, funding acquisition, W.T.: Project administration, funding acquisition, B.G.: Methodology, writing-review and editing, J.Y.: Supervision, funding acquisition, L.Z.: Project administration, resources, writing-review and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Xu, W., Liang, H. et al. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of 3D printed sheet and solid triply periodic minimal surfaces porous structures. Sci Rep 15, 29255 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15029-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15029-1