Abstract

Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), a modulator of motor symptoms and synaptic plasticity, may contribute to freezing of gait (FOG)—a significant gait disturbance in Parkinson’s disease with an unclear pathophysiology—and its associated impairments in balance learning. However, this potential relationship has not been investigated until now. This preliminary study explores the potential role of AQP4 in FOG and its associated balance learning deficits. The study involved fifteen patients with FOG, fifteen patients without FOG, and fifteen healthy controls. Serum AQP4 levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and balance learning was assessed using a voluntary dynamic balance task performed on a stabilometer. Notably, patients who were FOG-positive exhibited significantly higher serum AQP4 levels compared to the other two groups (p < 0.001). These elevated levels showed a positive correlation with FOG severity (ρ = 0.51, p = 0.004). Furthermore, the serum AQP4 levels were inversely correlated with both the slope (ρ = -0.65, p < 0.001) and rate (ρ = -0.46, p = 0.01) of balance learning in PwPD. FOG-positive individuals exhibited impaired voluntary balance learning compared to both FOG-negative and healthy participants. FOG-negative participants showed initial improvement, while healthy individuals demonstrated continuous enhancement across consecutive learning blocks (the first significant main effect of time on balance performance, comparing Blocks 1 and 2, was p = 0.02 for FOG-negative and p = 0.03 for healthy groups), with both groups maintaining their acquired skills over time. These findings suggest that AQP4 may play a significant role in FOG and its associated learning impairments, warranting further investigation for potential treatments. Additionally, alternative balance learning protocols may be necessary for FOG-positive patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), a water channel protein, plays a critical role in maintaining water homeostasis in the brain1. These channels are most abundantly located in the cell membranes of astrocytes1 and are highly expressed in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, as well as in various other organs. Their diverse sites of action highlight their importance in several physiological functions, including motor control2. Emerging evidence suggests that AQP4 is involved in the pathophysiology of various neurodegenerative diseases3, including Parkinson’s disease (PD)4. AQP4 deficiency may contribute to PD progression through multiple mechanisms5, as its post-translational modifications are crucial in the disease’s development. These modifications can lead to the formation of cytotoxic oligomers and aggregates that drive neurodegeneration5. Additionally, AQP4 regulates the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in astrocyte perivascular processes6. GFAP, an astroglial protein, has been identified as a potential biomarker for monitoring and predicting disease progression in PD7. Elevated GFAP levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood serum have been proposed as early biomarkers for neurological conditions such as PD8. Moreover, these increased GFAP levels correlate with the postural instability and gait disorder motor subtype9, which is strongly linked to freezing of gait (FOG)10,11,12,13, one of the most significant motor symptoms in people with PD (PwPD). A positive relationship has also been reported between FOG severity and blood GFAP levels14, suggesting a potential but yet uninvestigated connection between AQP4 and FOG. The underlying pathophysiology of FOG remains unclear. Notably, FOG, together with postural control and balance impairments, accounts for approximately 80% of falls in PwPD15 and is associated with deficits in balance learning. Identifying possible mechanisms, such as the role of AQP4 in FOG, and investigating its relationship to balance learning impairments in patients with FOG (FOG-positive) is therefore of great clinical interest for developing optimal treatment protocols. Animal studies suggest that AQP4 is involved in key synaptic plasticity mechanisms, including long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP), as well as in memory processes such as spatial retention and memory consolidation16,17,18. This raises the intriguing possibility that AQP4 may also play a critical role in learning processes among PwPD specifically those with FOG — an area that, despite its clinical importance, remains largely unexplored in human population.

Acquisition (encoding) and retention (consolidating) of balance performance — known as balance learning — are essential components of neurorehabilitation for PwPD, particularly those with FOG19. Motor learning is broadly categorized into two types: conscious/voluntary (explicit) learning, which involves conscious awareness and verbal instruction, and unconscious/involuntary (implicit) learning, which occurs without conscious awareness of what has been learned20. Unconscious learning is primarily associated with the basal ganglia, whereas conscious learning is more closely linked to the medial temporal lobe20. Given the degeneration of basal ganglia structures in PD, individuals with the disease, including those with FOG, may experience impairments in unconscious learning21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, leading them to rely more on conscious, attention-driven strategies29. For example, FOG-positive patients may exhibit greater deficits in involuntary lower limb tasks requiring symmetrical stepping or automatic protective steps to control backward center of mass (COM) displacement30,31,32 —key elements of postural control30, despite demonstrating some ability to unconsciously improve balance strategies30,33. Despite these challenges, PwPD can learn voluntary postural control (COM displacement) by consciously leaning toward a target34. This highlights the need for voluntary, attention-focused balance protocols critical for both therapy and daily functioning. However, research specifically focusing on this type of learning for improving balance in FOG-positive patients is limited. Some studies have combined voluntary approaches, like training limits of stability, with involuntary methods, such as reactive postural control35, or have utilized action observation focused on combining gait and balance maneuvers36,37,38,39. Nevertheless, none have specifically implemented a dedicated voluntary balance learning protocol aimed at enhancing balance in FOG-positive patients. This gap, along with the importance of task-dependent motor behavior changes during learning40, underscores the need for further research on focused voluntary balance learning in this population. Although most balance tasks operate unconsciously, adults become highly cautious when facing novel, complex balance challenges that require constant postural adjustments41 like using stabilometer. Notably, this approach has not yet been used to assess voluntary balance learning in FOG-positive patients or to explore its relationship with AQP4.

Alterations in brain AQP4 levels may be reflected in the blood42. However, the origin of blood AQP4 is unclear. It could diffuse across the blood-brain barrier via AQP4 vesicles43 and flow through CSF from the central nervous system to the blood8. Alternatively, it could be directly absorbed from CSF into the circulation through arachnoid villi driven by concentration gradients44. Environmental changes in the blood are widely accepted as markers of brain changes in PD and can help identify new biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases45. Therefore, we utilized serum AQP4 to achieve our objectives. Given the connection between AQP4 and GFAP — with elevated serum GFAP levels linked to FOG — along with AQP4’s key role in basic mechanisms of neuroplasticity and the known relationship between FOG and impaired balance learning, we defined two primary aims for this study. The first aim was to assess serum AQP4 levels in PwPD and to investigate their relationship with FOG. The second aim was to compare balance performance and learning ability during a voluntary, complex dynamic balance task using a stabilometer, and to explore how serum AQP4 levels relate to balance learning among PwPD with and without FOG. We hypothesized that patients with FOG would exhibit higher serum AQP4 levels compared to both FOG-negative patients and healthy controls, and that these elevated levels would correlate positively with FOG severity. Furthermore, we hypothesized that FOG-positive patients would demonstrate poorer voluntary balance performance and reduced balance learning ability relative to FOG-negative patients, potentially associated with AQP4 dysregulation.

Results

The mean (standard deviation, SD) of demographic and clinical variables is summarized in Table 1. A significant difference was found between the FOG-positive and healthy groups (p < 0.001) and between the FOG-negative and healthy groups (p = 0.01) only on the Mini Balance Evaluation Systems Test (Mini-BESTest). However, no significant difference was observed between the FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups on this test (p = 0.23). The groups showed no significant differences in disease severity, disease duration, cognition, anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, and sleep. Balance performance time across three days and the total scores of the NASA task load index (NASA-TLX) and its subcategories are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. There were also no significant differences in the NASA-TLX scores, which assess the perceived difficulty and challenge of the balance task. Therefore, any significant differences in learning parameters observed between the groups can be attributed exclusively to the presence of FOG. As a result, these parameters can be reliably compared between the FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups.

Serum AQP4 levels

The one-way ANOVA test revealed a significant difference in serum AQP4 levels between groups (F (2,42) = 11.71, p < 0.001, η² = 0.36). Multiple comparisons showed higher serum AQP4 levels in the FOG-positive (mean (SD) = 4.99 (1.47)) compared to the FOG-negative (mean (SD) = 3.33 (0.90)) and healthy groups (mean (SD) = 3.23 (0.90)), which was statistically significant (P = 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in AQP4 serum levels between the FOG-negative and healthy groups (P = 0.97). Correlation analyses across all variables in PwPD revealed significant associations between serum AQP4 levels and both Mini-BESTest scores (ρ = − 0.48, p = 0.01) and new freezing of gait questionnaire (NFOGQ) scores (ρ = 0.51, p = 0.004). A stepwise regression model explained 32.2% of the variance in serum AQP4 levels, identifying FOG severity and balance function as the strongest predictors, respectively (see Table 4).

Although the difference in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores was not statistically significant, the FOG-positive group showed a trend toward higher scores (see Fig. 1-C). To further explore this, we conducted a two-way ANOVA to examine the effects of group (FOG-positive, FOG-negative, and healthy controls) and sleep status (with and without sleep problems) as between-subject factors. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of group (F (2, 39) = 11.44, p < 0.001, η² = 0.37), indicating differences in serum AQP4 levels among the groups (Fig. 1-B). However, there was no significant main effect of sleep status (F (1, 39) = 0.28, p = 0.60, η² = 0.01) (Fig. 1-A), nor was there a significant interaction between group and sleep status (F (2, 39) = 1.67, p = 0.20, η² = 0.08) (Fig. 1-C). Post hoc comparisons showed that FOG-positive individuals had significantly higher serum AQP4 levels compared to both FOG-negative patients (p = 0.001) and healthy controls (p < 0.001), regardless of sleep status. Notably, within each group, there was no significant difference in AQP4 levels between participants with and without sleep problems. In the FOG-positive group, there was a trend toward lower serum AQP4 levels in patients with sleep disturbances, aligning with previous research in chronic insomnia disorder42. However, this trend did not reach statistical significance and warrants further investigation (Fig. 1-C). Therefore, serum AQP4 levels were not influenced by sleep problems or other variables in this study, except for FOG severity—which was the main outcome measure—and balance performance, which did not differ significantly between the FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups. Thus, we can confidently attribute higher serum AQP4 levels to the presence of FOG.

Comparison of the mean and standard deviation of serum Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) levels across groups differentiated by the presence or absence of sleep problems (main effect of sleep status) (A), by the presence or absence of freezing of gait (FOG) and healthy controls (main effect of FOG) (B), and by the interaction effect of Group × Sleep (C)

Balance performance

The mixed ANOVA test revealed significant main effects of group (F (2,42) = 16.11/25.68, p < 0.001/<0.001, η² = 0.43/0.55), time (F (4,168) = 22.49/6.79, p < 0.001/<0.001, η² = 0.35/0.14), and the group*time interaction (F (8,168) = 5.83/2.45, p < 0.001/=0.03, η² = 0.22/0.10) on balance performance time during the first/seventh days, respectively. Multiple comparisons showed significantly lower initial balance performance in PwPD compared to healthy subjects (FOG-positive compared to healthy: P = 0.04 and FOG-negative compared to healthy: P = 0.002), with no significant differences between FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups (P = 0.86). Pairwise comparisons on the first day showed no significant improvement in balance performance time in the FOG-positive group. In contrast, the FOG-negative group showed significant improvement only in the initial blocks (B1D1–B2D1: p = 0.02; B1D1–B3D1: p < 0.001; B1D1–B4D1: p = 0.01; B1D1–B5D1: p < 0.001). Healthy participants, however, demonstrated continuous improvement, with balance time in each block significantly better than the previous one (B1D1–B2D1: p = 0.03; B1D1–B3D1: p < 0.001; B1D1–B4D1: p < 0.001; B1D1–B5D1: p < 0.001; B2D1–B5D1: p < 0.001; B3D1–B5D1: p = 0.001; B4D1–B5D1: p = 0.02), except between B2D1–B3D1, B2D1–B4D1, and B3D1–B4D1.

On the seventh day, pairwise comparisons indicated possible improvement in the healthy group, mainly in the early blocks and between B2D7 and B5D7, except for B1D7–B2D7 (B1D1–B3D1: p = 0.003; B1D1–B4D1: p = 0.01; B1D1–B5D1: p = 0.001; B2D1–B5D1: p = 0.04). No such differences were observed in the FOG-positive or FOG-negative groups. A one-way ANOVA on the second day also demonstrated a significant difference between groups in balance performance (B1D2): (F (2,42) = 26.05, p < 0.001, η² = 0.55). Multiple comparisons revealed significant differences between PwPD, including both FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups, and healthy subjects (p < 0.001), but not between FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups (Fig. 2).

Mixed ANOVA comparison of the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) for balance performance time across different blocks of the voluntary balance task over three days, both within and between groups of healthy participants and Parkinson’s disease patients with and without freezing of gait (FOG).

Acquisition stage of balance learning during the first and 7th day

The one-way ANOVA test for acquisition stage of learning revealed significant differences in the slope (F (2,42) = 31.38, p < 0.001, η² = 0.60) and rate (F (2,42) = 18.33, p < 0.001, η²=0.47) of balance learning among the three groups on the first day. Multiple comparisons showed that balance learning ability was significantly poorer in FOG-positive compared to FOG-negative (balance learning rate: P = 0.005, balance learning slope: P = 0.008) and healthy groups (balance learning rate: P < 0.001, balance learning slope: P < 0.001). Additionally, this ability was significantly lower in FOG-negative compared to healthy participants (balance learning rate: P = 0.03, balance learning slope: P < 0.001). A significant difference in the 7th day learning slope (χ2 = 7.10, p = 0.03) was observed between groups. Healthy subjects demonstrated a significantly higher ability to improve balance performance with continuous training compared to the other two groups (healthy and FOG-positive: P = 0.01, healthy and FOG-negative: P = 0.05), while no such differences were observed between the FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups (P = 0.44). Additionally, no significant difference was found between groups for learning rate on the 7th day (χ2 = 2.01, p = 0.37) (Table 5).

Correlation analysis in PwPD were also found significant association between the balance learning slope on the first day and FOG severity (ρ = − 0.45, p = 0.01). Additionally, the balance learning rate on the first day showed significant correlations with both disease duration (r = − 0.40, p = 0.03) and FOG severity (ρ = − 0.53, p = 0.002). Furthermore, stepwise regression models explained 18.30% and 24.60% of the variance in the balance learning slope and rate, respectively, with FOG severity emerging as a significant predictor (p = 0.02 and p = 0.01).

Retention stage of balance learning (1-day- and 7-day retention)

The one-way ANOVA test for retention showed no significant difference between groups for second-day (F (2,42) = 0.24, p = 0.79, η² = 0.01) and seventh-day retention (F (2,42) = 2.15, p = 0.13, η² = 0.09). This indicates that 1-day- and 7-day retention remained stable across groups without change (Table 5).

Correlation analysis between serum AQP4 levels and balance learning parameters in PwPD

Spearman analysis revealed a significant moderate negative correlation was observed between serum AQP4 levels and both the slope (ρ = −0.65, p < 0.001) and rate (ρ = −0.46, p = 0.01) of balance learning on the first day in PwPD. However, no significant correlations were found between serum AQP4 levels and the rate (ρ = 0.01, p = 0.95) or slope (ρ = −0.08, p = 0.68) of balance learning on the seventh day, nor with one-day (ρ = 0.02, p = 0.90) or seven-day (ρ = 0.24, p = 0.21) retention (Fig. 3).

Discussion

AQP4, a key water channel protein, plays an important role in motor performance and fundamental neuroplasticity mechanisms. Despite these critical functions, its role in the pathophysiology of FOG—a major yet poorly understood motor symptom of PD—and the associated balance learning impairments remains unclear. This study investigated the role of AQP4 in FOG and its relationship to voluntary dynamic balance learning using a stabilometer. The results indicate that serum AQP4 levels are elevated in FOG-positive patients, showing a positive correlation with FOG severity. Furthermore, higher serum AQP4 levels are inversely associated with voluntary balance learning ability in PwPD.

AQP4 concentration

Our pilot study demonstrated higher serum AQP4 levels in FOG-positive compared to FOG-negative and healthy individuals, consistent with previous research. Additionally, serum AQP4 levels were positively correlated with FOG severity, which emerged as the strongest predictor of AQP4 concentration. Elevated AQP4 expression as a common feature of neurodegenerative disorders, including PD4, demonstrated in the brain, CSF, and blood. Increased AQP4 levels were found in layers 5 and 6 of the temporal neocortex in PwPD, negatively correlating with α-synuclein aggregation4. On the other hand, a decreased blood α-synuclein level was demonstrated in FOG-positive46. Elevated AQP4 in the CSF has also been reported in frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and AD47,48, positively correlating with basal ganglia perivascular enlargement47. This perivascular enlargement has also been associated with the presence and severity of FOG in PD49. Additionally, increased serum AQP4 levels in patients after ischemic43 and thrombosis stroke demonstrated a relationship to severe neurological symptoms50. A positive relationship has also been observed between the FOG severity and blood GFAP levels14 which is regulated by AQP46. However, Thamizh et al.‘s results showed decreased AQP4 mRNA expression in PwPD blood, without considering FOG51, which might stem from methodological differences and the fact that mRNA expression and protein levels may not always align. This is because various factors, such as protein localization, can influence protein expression52. We propose that elevated AQP4 levels and their redistribution between the brain and bloodstream (in either direction) may contribute to FOG through several interconnected mechanisms, including: (1) neuroprotective responses, (2) blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, and (3) an initial rise in peripheral blood before brain involvement. Each of these mechanisms requires further investigation to clarify the precise underlying pathways.

-

1.

Neuroprotection: AQP4 levels may rise in the brain to accelerate the clearance of α-synuclein and amyloid-beta, both of which are linked to FOG46,53. Elevated levels of these proteins can increase FOG risk by disrupting synaptic function, promoting protein misfolding, and indirectly impairing cognitive processes54,55,56 critical for balance learning. The resulting excess AQP4 in the brain may then pass into the bloodstream along a concentration gradient.

-

2.

BBB leakage: BBB breakdown has been observed in PwPD, particularly in the substantia nigra57. Such impairment allows proteins, including AQP4, to leak into the lymphatic system, raising their levels in the blood43,50. Conversely, AQP4 deficiency or dysregulation (reflected as increased levels) may further compromise the BBB by weakening tight junctions or causing swelling of astrocytic end-feet6, creating a vicious cycle. Ultimately, BBB disruption can trigger inflammation, which may contribute to FOG58 and affect future balance learning by influencing motivation and motor skill acquisition59.

-

3.

Peripheral origin: According to the Braak hypothesis, PD may have a peripheral origin60. Misfolded alpha-synuclein may arise from the enteric plexus or erythrocytes and migrate to the brain, where it accumulates in PwPD61 (mechanism 1). Peripheral inflammation can also disrupt the BBB, contributing to both PD progression62 and FOG58 (mechanism 2). Both pathways may ultimately increase AQP4 levels in the blood, leading to FOG and affect balance learning ability. Additionally, AQP4 levels may initially rise in the blood of FOG-positive patients and later migrate to the brain, similar to patterns observed in neuromyelitis optica patients63, who present with Parkinson-like symptoms.

In summary, elevated serum AQP4 levels, along with these mechanisms, may ultimately contribute to FOG and affect balance learning ability in PwPD—learning-related processes that will be further discussed in the following section.

The association between serum AQP4 levels and both balance performance and balance learning

The first study assessed the role of AQP4 in motor learning related to balance in humans. We observed that elevated serum AQP4 levels were negatively correlated with both balance ability (measured by the Mini-BESTest), which emerged as the second strongest predictor of serum AQP4 concentration, and balance learning metrics (rate and slope) in PwPD. However, as these conclusions is based on a single significant correlation, it should be interpreted with caution and requires further investigation.

AQP4 plays a significant role in somatosensory, motor, psychological, and cognitive functions, all critical components of balance2,64,65,66. This supports the observed relationship between AQP4 and balance ability. Furthermore, AQP4 may be crucial during various learning stages—including acquisition motivation67, retention, and consolidation16,17—through multiple mechanisms. These include: regulation of dopamine (crucial for learning and motivation68, LTP and LTD (as physiological processes of motor skill learning18, neurogenesis and neuronal migration in the dentate gyrus (a vital region for acquisition, memory storage, and consolidation)69; clearance of amyloid plaques (a significant factor in both FOG53 and learning deficits70; and modulation of inflammation, which can reduce dopamine availability in corticostriatal pathways, impairing motivation and motor skill acquisition59. Thus, AQP4 dysregulation can be associated to motor learning through various mechanisms. The only animal study demonstrated that cerebral damage following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus acutely reduced AQP4 expression in the piriform cortex and hippocampus, potentially leading to motor learning impairments71. These results may be due to the selection of different species and types of pathologies/models, which warrant further investigation.

Balance performance

The results indicate that PwPD exhibit poorer balance performance, as evidenced by stabilometer and Mini-BESTest assessments, compared to healthy individuals, consistent with previous research72. However, FOG-positive and FOG-negative patients showed no significant baseline balance differences. FOG-positive may have greater postural instability in the anterior-posterior direction compared to the medio-lateral direction73. The medio-lateral nature of the task and the relatively low NFOGQ scores among FOG-positive patients may have resulted in this similar baseline balance abilities74. FOG-positive patients showed no ability to improve their balance performance compared to FOG-negatives, who exhibited balance performance improvement during the initial training blocks on the first day, according to a previous study75. FOG-positive individuals exhibit specific directional-control deficits during voluntary weight shifting, as well as impairments in scaling and timing of postural responses76. Additionally, the presence of FOG has a more pronounced negative impact on dynamic balance compared to static balance, due to impairments in weight shifting77, which all may result in an inability to react promptly and in a timely manner to reverse the stabilometer to a balanced position, thereby hindering performance improvement. Compensatory increases in cerebellar activity, involved in initial learning, and the relatively intact caudate nucleus may have contributed to early performance improvements in FOG-negative individuals78,79 — areas that are impaired in FOG-positive patients80,81. In contrast, putamen dysfunction, which degenerates sooner, likely resulted in fewer sustained improvements79. On the 7th day, PwPD did not exhibit any significant improvement in balance performance, indicating no improving effect of continuous training on balance function in contrast to healthy subjects.

Acquisition stage of balance learning

PwPD, particularly those with FOG, demonstrated impaired voluntary dynamic balance learning compared to healthy subjects. Interestingly, impaired balance learning was positively correlated with FOG severity, as suggested by a previous study focused on upper limb learning82. Given that the groups did not exhibit significant differences in factors potentially influencing the learning process—such as disease severity, disease duration, cognitive function, anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, or sleep disturbances—any observed differences in balance learning can be attributed to the presence of FOG. The only significant difference noted was in the Mini-BESTest scores between the healthy control group and both the FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups. However, there was no significant difference in Mini-BESTest scores between the FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups, which were the primary focus of our study. However, this difference does not compromise the validity of our study’s conclusions due to the methodological approach employed. By calculating learning parameters (e.g., learning rate and slope) separately within each group prior to conducting between-group comparisons, we effectively controlled for potential confounding variables, including baseline balance ability. This methodological strategy ensures that the learning parameters can be validly compared between groups. Bradykinesia, akinesia, and reduced proprioceptive and sensory inputs can affect the acquisition phase, contributing to decreased balance learning in these patients83. The circuits involved in motor learning, particularly dynamic balance tasks, are more affected in PwPD, especially in FOG-positive individuals. Key regions for motor learning, such as the cerebellum, striatum, and their interconnected circuits (cortico-cerebello-thalamo-cortical and cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical), along with the hippocampus, can be more affected in FOG-positive84,85,86,87. FOG is also associated with functional impairments of the circuits connecting the frontal lobe and the basal ganglia88, while the prefrontal cortex is crucial in stabilometer performance as an attention-demanding task89. The increase in pre-motor cortex activity is also related to FOG and dynamic balance performance90, potentially causing more dynamic balance learning impairment in FOG-positive. Dynamic balance learning is associated with changes in gray matter volume of the cerebellum and hippocampus85, regions that are impaired in FOG-positive patients91,92 but remain relatively intact in FOG-negative individuals93. These brain regions can help offset striatal dysfunction during the initial stage of motor learning. However, the decreased balance learning ability in FOG-negative compared to healthy participants suggests that this compensation does not fully compensate for the dysfunction94. This reduced efficiency also occur due to the recruitment of different neural networks during learning compared to healthy controls95. These mechanisms can hinder the improvement of balance learning in PwPD compared to healthy controls.

Retention stage of balance learning (1-day retention and 7-day retention)

One-day retention and 7-day retention remained stable in PwPD and healthy participants. Consolidation, a progressive post-acquisition stabilization of memory96, is initially dependent on the hippocampus and then the cerebellum, and is reinstated in the neocortex96,97,98, with a contributing effect of the basal ganglia in the early consolidation, long-term retention, and development of automaticity99,100. Therefore, the ability to store information undamaged in FOG-negative after 24 h and 1 week further supports the idea that the hippocampus and cerebellum are perfectly stable, compensating for the dysfunctional striatum93. In this regard, previous research has found that PwPD can retain skills task-dependently101 and have the potential to maintain even complex balancing tasks30,34.

For the first time, elevated serum AQP4 levels were observed in FOG-positive patients and showed a positive correlation with FOG severity. Serum AQP4 levels also exhibited a negative correlation with voluntary balance learning ability. Modulating inflammation in peripheral organs and the brain may offer a promising approach for developing novel therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases, particularly PD102. Our findings suggest that modulating AQP4 could provide a new avenue for addressing FOG and associated motor learning deficiencies, potentially aiding in the development of new treatments. However, these results are preliminary and require further investigation in the brain, CSF, and blood. We also investigated a novel balance learning protocol for FOG-positive patients and found they have a reduced ability to voluntarily learn dynamic balance compared to FOG-negative individuals. While FOG-negative subjects show some balance enhancement and learning capacity, it is less than in healthy individuals. These results can be attributed to learning impairments in PwPD, particularly those with FOG, given the lack of significant differences between groups in factors influencing balance function and learning, including cognition.

The study’s limitations, including the small sample size and the focus solely on the ON-drug phase—which is susceptible to placebo effects and biases—highlight the need for further research to enhance the generalizability of our findings. Future studies should explore a range of tasks based on both voluntary and involuntary learning protocols and investigate the role of AQP4 in the brain and CSF using larger sample sizes in FOG-positive individuals. These studies should include longitudinal follow-up and employ more precise methods; such as center of mass measurements. Additionally, identifying FOG phenotypes or including patients with upper limb freezing in future studies could help further elucidate the role of AQP4 across different FOG subtypes.

Methods

Participant

Thirty PwPD (18 men and 12 women), with a mean age of 59.67 years (± 11.23), were recruited through consecutive sampling for this pilot study from Iranian rehabilitation and movement disorders clinics. The participants were selected based on the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Diagnostic Criteria103 during a six-month period. The eligibility criteria for inclusion were: the ability to stand unassisted for 1 h, mild-moderate PD stage (Hoehn and Yahr stage I–III), postural instability score ≤ 1 on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) (Part 3, question 30), no history of falls over the past six months, and no familiarity with a stabilometer. Exclusion criteria included a history of deep brain stimulation, upper limb freezing due to our focus on gait specific problems, other neurological diseases, conditions that affect AQP4 levels, such as optic neuritis, orthopedic impairments affecting balance, cognitive impairment (Montreal cognitive assessment battery (MoCA) score < 24104, severe anxiety/depression (Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS-A/D) score > 7105, and loneliness (De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale total score ≥ 3106 due to its documented impact on balance107. Additional exclusion criteria were a history of all musculoskeletal surgery and substance use within the past year. PwPD were classified as FOG-negative (score = 0; n = 15) and FOG-positive (score = 1; n = 15) based on their responses to item 1 of the NFOGQ108 after viewing a video of different FOG episodes. The presence of FOG was confirmed through direct observation during a clinical examination by a movement disorder neurologist. We focused on FOG-positive patients whose condition did not increase the risk of falls during the task. Patients who experienced a fall during the task or were unable to recover the stabilometer due to severe FOG were excluded from the study (n = 2 from the FOG-positive group). Age, body mass index (BMI), and sex were matched across groups due to their impact on balance. All PwPD were levodopa-responsive and did not take antianxiety, antidepressant, or AQP4-affecting medications. Fifteen age, sex, and BMI-matched healthy controls without cognitive impairment (MoCA ≥ 24104, a history of falls over the past six months, musculoskeletal or neurological disorders, loneliness (DJG total score ≥ 3106, and anxiety/depression (HADS-A/D ≤ 7105 also participated.

The most affected side was determined by a summed lateralized UPDRS-III score (items 20–26). Levodopa equivalent dose (LED) was calculated using the formula by Tomlinson et al.109. Balance function, executive function, pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, and quality of life were evaluated using Mini-BESTest, Trail Making Test (TMT), visual analog scale for pain (VAS-p), fatigue severity scale (FSS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), PSQI, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), sleep duration after training and before retention, and the 39-item PD Quality of Life Questionnaire (PDQ-39). Blood samples (10 cc) were collected between 8 and 9 A.M. from the venous blood of the hand in all groups on the same day that participants began the balance learning protocol. The samples were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the serum was separated and stored at −80 °C43. Serum AQP4 levels were examined in duplicate using an ELISA kit (ZellBio GmbH, Germany, cat. No: ZB-10616 C-H9648) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

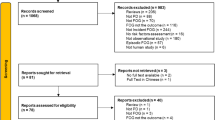

Balance learning task

The study utilized a stabilometer, which required constant postural adjustments (COM displacement) in the medio-lateral direction, making it an attention-demanding balance task41. This is a widely used, ecologically valid tool for investigating complex dynamic balance skills110. The learning process, consisting of different blocks of balance performance, spanned three days, based on previous studies related to balance learning in PD111,112. A pilot study was also conducted on PwPD with and without FOG to further validate the number and duration of balance performance blocks. Initially, the stabilometer was calibrated. Participants then stood on a 15-degree platform with their eyes open and were instructed to keep the platform as horizontal as possible while wearing a safety harness. Each participant’s initial comfortable foot position was marked and used consistently across all trials and testing days. A millisecond-precision timer integrated into the stabilometer recorded the duration within each 30-second trial that participants maintained the platform within ± 5° of horizontal (balance maintenance time). The balance learning protocol was completed over three days (Fig. 4). On the first day (D1), participants completed two familiarization trials to become accustomed to the equipment and ensure they understood the instructions for maintaining balance. This was followed by 15 trials, divided into five blocks (B1–B5), aimed at increasing balance maintenance time and assessing balance learning in the first day. On the second day (D2), they completed two familiarization trials and one block of three trials to assess 1-day retention. On the seventh day (D7), they completed a similar protocol to the first day to assess 7-day retention and the potential to balance performance improvements with continued practice. After each trial, participants received standardized, firm feedback—based on their acquired balance time recorded by the millisecond timer—encouraging them to maintain their current balance strategy while striving to improve performance in subsequent trials. There were 60-second breaks between trials and 120-second breaks between blocks. All three sessions were conducted at the same time of day for each participant.

Following each balance task training session, participants completed the NASA-TLX, a visual analog scale assessing subjective workload and task difficulty in balance tasks113, due to the importance of task challenge in motor learning. A total of six aspects were averaged in the assessment, with each rating ranging from 0 (not demanding) to 20 (very demanding), representing mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration. All assessments and protocols were performed in the ON-state (One hour after taking dopaminergic medication) to minimize the bias of motor symptom effects and safely perform the balance task. Participants did not receive any rehabilitation, including balance exercises, during this procedure. The assessor was blinded to the study’s aim. If errors occurred, such as displacement of the participant’s foot or leaning on the harness, the individual was excluded from the study (two participants in the FOG-positive group were excluded).

Data processing

The mean balance maintenance time per block—calculated from the durations of three trials recorded by a millisecond-precision timer—was used as the balance performance time, in accordance with established methodologies111,112. We then assessed balance learning parameters separately for each group, including acquisition (learning rate and slope) and retention (measured on the first and seventh days).

The balance learning rate was calculated as the percentage change in balance performance time from the first block to the fifth block on either the first or seventh day, using the following formula36,114:

Additionally, the learning slope for the first or seventh day was determined by calculating the slope of the linear fit (tan θ) of balance performance changes from the first to the fifth block on the respective day114.

One-day retention was assessed by calculating the percentage change in balance performance from the final block on the first day (block5_day1) to the first block on the second day (block1day2), using the formula:

Similarly, seventh-day retention was evaluated by calculating the percentage change in balance performance from the final block on the first day (block5_day1) to the first block on the seventh day (block1day7), using the formula:

Statistical analysis

A type I error probability of 0.05, a type II error probability (statistical power) of 0.80, and a dropout rate of 10% were used in a prior power analysis. The analysis, based on a pilot study for the SD of balance maintenance time, indicated that 15 subjects were necessary for each group. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for all demographic variables, learning parameters (balance learning rate and slope on the first and seventh days, as well as one-day and seven-day retention), balance performance time (B1 to B5), and serum AQP4 concentrations. To evaluate group differences in demographic variables (e.g., age), balance learning parameters, and AQP4 levels, appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests were applied. The independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to assess group differences for normally distributed continuous data. For non-normal distributions of continuous data, the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed. The chi-square test was also used to evaluate categorical variables.

Separate mixed ANOVAs were performed to evaluate balance performance both between and within groups on the first and seventh days. The group (FOG-negative, FOG-positive and healthy) was treated as a between-subject factor, while time (B1-B5) was treated as a within-subject factor. Due to the non-normal distribution of the first day’s balance performance data (B1D1–B5D1) and the absence of an appropriate non-parametric alternative for mixed ANOVA, a logarithmic transformation was applied. In contrast, the 7th day data met the assumptions of normality, allowing for the application of mixed ANOVA without the need for data transformation. One-way ANOVA tests were also conducted to compare groups for learning rate and slope in the first day, 1-day and 7-day retention, and serum AQP4 levels, given the normal distribution of these variables within each group. A two-way ANOVA was also conducted to examine the effects of group (healthy, FOG-negative, and FOG-positive) and sleep status (with and without sleep problems) on AQP4 levels, as the data were normally distributed within each group. For all one-way, two-way and mixed ANOVA tests, post hoc analyses were performed using Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Partial eta squared (η2), which is divided into three categories: small (η2 > 0.01), medium (η2 ≥ 0.06), and large (η2 ≥ 0.14), was used to calculate the effect size115. Additionally, a Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni adjustment was performed for comparison between groups for the rate and slope of learning on the 7th day (due to the non-normal distribution of data). The correlation between serum AQP4 levels and both the severity of FOG (NFOGQ scores) and balance learning parameters—the rate and slope of learning, as well as retention on days one and seven—was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation in PwPD, encompassing both FOG-positive and FOG-negative groups, due to the non-normal distribution of AQP4 data in PwPD participant. We conducted additional correlation analyses between AQP4 levels and balance learning parameters with various variables—including sex, marital status, educational level, disease duration, and others—were assessed across all PwPD. Depending on the distribution of the data, either Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients were applied: Spearman’s rank correlation was used for AQP4 and balance learning slope (owing to non-normality), while the learning rate, which was normally distributed, was analyzed using the appropriate correlation based on each variable’s distribution. For variables that were normally distributed, including age, BMI, LED, disease duration, UPDRS, TMT-A/B, FSS, DjG, STAI, BDI, PSQI, ESS, and PDQ-39, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was applied to other variables that were not normally distributed- mini-BESTest, NFOGQ, VAS-p and hours of sleep. Variables that showed significant correlations with AQP4 concentrations or learning parameters were then separately entered into stepwise regression models to identify potential predictors (R²). The power of correlations was categorized as weak, moderate, and strong, with corresponding values of 0.10–0.39, 0.40–0.69, and ≥ 0.70, respectively116. The level of statistical significance was considered at P ≤ 0.05.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT-4 and QuillBot to improve the structure and grammar of our manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Ethic declarations

The Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as amended in 2013, and the ethical guidelines established by the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, according to the authors, apply to all procedures used in this work. An informed consent was filled out by participants, and all experiment protocols involving patients or human subjects were approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences’ Ethics Committee (IR.IUMS.REC.1402.497).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author. Please note that the data are not publicly accessible due to privacy and ethical considerations.

References

Iacovetta, C., Rudloff, E. & Kirby, R. The role of Aquaporin 4 in the brain. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 41 (1), 32–44 (2012).

Jazaeri, S. Z. et al. Aquaporin 4 Beyond a Water Channel; Participation in Motor, Sensory, Cognitive and Psychological Performances, a Comprehensive Review271p. 114353 (Physiology & Behavior, 2023).

Natale, G. et al. Glymphatic system as a gateway to connect neurodegeneration from periphery to CNS. Front. NeuroSci. 15, 639140 (2021).

Hoshi, A. et al. Expression of Aquaporin 1 and Aquaporin 4 in the Temporal neocortex of patients with parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol. 27 (2), 160–168 (2017).

Lapshina, K. V. & Ekimova, I. V. Aquaporin-4 and parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (3), 1672 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Altered blood–brain barrier integrity in adult aquaporin-4 knockout mice. Neuroreport 19 (1), 1–5 (2008).

Lin, J. et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein as a biomarker of disease progression in parkinson’s disease: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 21 (1), 420 (2023).

Lotankar, S., Prabhavalkar, K. S. & Bhatt, L. K. Biomarkers for parkinson’s disease: recent advancement. Neurosci. Bull. 33, 585–597 (2017).

Che, N. N. & Shang, H. The potential use of plasma GFAP as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of motor subtype in early Parkinson’s disease. (2023).

Lord, S. R. et al. Freezing of gait in people with parkinson’s disease: nature, occurrence, and risk factors. J. Parkinson’s Disease. 10 (2), 631–640 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Clinical features and related factors of freezing of gait in patients with parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. 11 (11), e2359 (2021).

Wang, F. et al. Predicting the onset of freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 22 (1), 1–12 (2022).

Wang, F. et al. Predicting the onset of freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 22 (1), 213 (2022).

Ou, R. et al. Longitudinal Analysis of Plasma Biomarkers for Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease.

Michałowska, M. et al. Falls in parkinson’s disease. Causes and impact on patients’ quality of life. Funct. Neurol. 20 (4), 163–168 (2005).

Fan, Y. et al. Aquaporin-4 promotes memory consolidation in Morris water maze. Brain Struct. Function. 218 (1), 39–50 (2013).

Xu, Z. et al. Deletion of aquaporin-4 in APP/PS1 mice exacerbates brain Aβ accumulation and memory deficits. Mol. Neurodegeneration. 10 (1), 58 (2015).

Szu, J. I. & Binder, D. K. The role of astrocytic aquaporin-4 in synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Front. Integr. Nuerosci. 10, 8 (2016).

Paul, S. S., Dibble, L. E. & Peterson, D. S. Motor learning in people with parkinson’s disease: implications for fall prevention across the disease spectrum. Gait Posture. 61, 311–319 (2018).

Olson, M., Lockhart, T. E. & Lieberman, A. Motor learning deficits in parkinson’s disease (PD) and their effect on training response in gait and balance: a narrative review. Front. Neurol. 10, 62 (2019).

Nissen, M. J. & Bullemer, P. Attentional requirements of learning: evidence from performance measures. Cogn. Psychol. 19 (1), 1–32 (1987).

Reber, P. J. & Squire, L. R. Parallel brain systems for learning with and without awareness. Learn. Mem. 1 (4), 217–229 (1994).

Reber, P. J. & Squire, L. R. Encapsulation of implicit and explicit memory in sequence learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 10 (2), 248–263 (1998).

Brown, R. G. et al. Pallidotomy and incidental sequence learning in parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport 14 (1), 21–24 (2003).

Doyon, J. et al. Role of the striatum, cerebellum, and frontal lobes in the learning of a visuomotor sequence. Brain Cogn. 34 (2), 218–245 (1997).

Ferraro, F. R., Balota, D. A. & Connor, L. T. Implicit memory and the formation of new associations in nondemented parkinson′ s disease individuals and individuals with senile dementia of the alzheimer type: A serial reaction time (SRT) investigation. Brain and cognition, 21(2) 163–180. (1993).

Sarazin, M. et al. Procedural learning and striatofrontal dysfunction in parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disorders: Official J. Mov. Disorder Soc. 17 (2), 265–273 (2002).

Vakil, E. et al. Motor and non-motor sequence learning in patients with basal ganglia lesions: the case of serial reaction time (SRT). Neuropsychologia 38 (1), 1–10 (2000).

Wu, T., Hallett, M. & Chan, P. Motor automaticity in parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 82, 226–234 (2015).

Peterson, D. & Horak, F. Effects of freezing of gait on postural motor learning in people with parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 334, 283–289 (2016).

Mohammadi, F. et al. Motor switching and motor adaptation deficits contribute to freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 29 (2), 132–142 (2015).

Smulders, K. et al. Postural inflexibility in PD: does it affect compensatory stepping? Gait Posture. 39 (2), 700–706 (2014).

de Ribeiro, C. et al. Perturbation-based balance training leads to improved reactive postural responses in individuals with parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait. Eur. J. Neurosci. 57 (12), 2174–2186 (2023).

Jessop, R. T., Horowicz, C. & Dibble, L. E. Motor learning and Parkinson disease: refinement of movement velocity and endpoint excursion in a limits of stability balance task. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 20 (4), 459–467 (2006).

Schlenstedt, C. et al. Moderate frequency resistance and balance training do not improve freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Front. Neurol. 9, 1084 (2018).

Mezzarobba, S. et al. Action observation plus sonification. A novel therapeutic protocol for parkinson’s patient with freezing of gait. Front. Neurol. 8, 723 (2018).

Mezzarobba, S. et al. Action observation improves sit-to-walk in patients with parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait. Biomechanical analysis of performance. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 80, 133–137 (2020).

Pelosin, E. et al. Action observation improves freezing of gait in patients with parkinson’s disease. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 24 (8), 746–752 (2010).

Pelosin, E. et al. Effect of Group-Based rehabilitation combining action observation with physiotherapy on freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. Neural Plast. 2018 (1), 4897276 (2018).

Kurtzer, I., DiZio, P. & Lackner, J. Task-dependent motor learning. Exp. Brain Res. 153, 128–132 (2003).

Wulf, G. et al. Attentional focus on suprapostural tasks affects balance learning. Q. J. Experimental Psychol. Sect. A. 56 (7), 1191–1211 (2003).

Yang, S. et al. Aquaporin-4, connexin-30, and connexin-43 as biomarkers for decreased objective sleep quality and/or cognition dysfunction in patients with chronic insomnia disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 856867 (2022).

Ramiro, L. et al. Circulating Aquaporin-4 as A biomarker of early neurological improvement in stroke patients: A pilot study. Neurosci. Lett. 714, 134580 (2020).

Silverberg, G. D. et al. Alzheimer’s disease, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, and senescent changes in CSF circulatory physiology: a hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 2 (8), 506–511 (2003).

Caronti, B. et al. Reduced dopamine in peripheral blood lymphocytes in parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport 10 (14), 2907–2910 (1999).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Using gastrocnemius sEMG and plasma α-synuclein for the prediction of freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS One. 9 (2), e89353 (2014).

Sacchi, L. et al. Association between enlarged perivascular spaces and cerebrospinal fluid aquaporin-4 and tau levels: report from a memory clinic. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1191714 (2023).

Arighi, A. et al. Aquaporin-4 cerebrospinal fluid levels are higher in neurodegenerative dementia: looking at glymphatic system dysregulation. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14 (1), 1–10 (2022).

Lin, F. et al. Enlarged perivascular spaces are linked to freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 13, 985294 (2022).

He, Y. et al. Effect of blood pressure on early neurological deterioration of acute ischemic stroke patients with intravenous rt-PA thrombolysis May be mediated through oxidative stress induced blood-brain barrier disruption and AQP4 upregulation. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 29 (8), 104997 (2020).

Thamizh Thenral, S. & Vanisree, A. Peripheral assessment of the genes AQP4, PBP and TH in patients with parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 37, 512–515 (2012).

Huang, J. et al. The internalization and lysosomal degradation of brain AQP4 after ischemic injury. Brain Res. 1539, 61–72 (2013).

Kim, R. et al. CSF β-amyloid42 and risk of freezing of gait in early Parkinson disease. Neurology 92 (1), e40–e47 (2019).

Hatcher-Martin, J. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait: an exploratory analysis. NPJ Parkinson’s Disease. 7 (1), 105 (2021).

Ti, Y. et al. Correlation of plasma α-Synuclein with cerebral blood flow in patients with Parkinson disease with freezing of gait. Clin. Lab., 71(3). (2025).

Clinton, L. K. et al. Synergistic interactions between Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein: acceleration of neuropathology and cognitive decline. J. Neurosci. 30 (21), 7281–7289 (2010).

Al-Bachari, S. et al. Blood–brain barrier leakage is increased in parkinson’s disease. Front. Physiol. 11, 593026 (2020).

Factor, S. A., Weinshenker, D. & McKay, J. L. A possible pathway to freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinson’s Disease. 15 (2), 282–290 (2025).

Felger, J. C. & Treadway, M. T. Inflammation effects on motivation and motor activity: role of dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 (1), 216–241 (2017).

Braak, H. et al. Idiopathic parkinson’s disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types May be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J. Neural Transm. 110, 517–536 (2003).

Ritz, B. et al. α-Synuclein genetic variants predict faster motor symptom progression in idiopathic Parkinson disease. PloS One. 7 (5), e36199 (2012).

Huang, X., Hussain, B. & Chang, J. Peripheral Inflammation and blood–brain Barrier Disruption: Effects and Mechanisms 27 36–47 (CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 2021). 1.

Bejerot, S. et al. Neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorder with increased aquaporin-4 microparticles prior to autoantibodies in cerebrospinal fluid: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 13, 1–9 (2019).

Paul, S. S. et al. Motor and cognitive impairments in Parkinson disease: relationships with specific balance and mobility tasks. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair. 27 (1), 63–71 (2013).

Nallegowda, M. et al. Role of sensory input and muscle strength in maintenance of balance, gait, and posture in parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 83 (12), 898–908 (2004).

Šumec, R. et al. Psychological benefits of nonpharmacological methods aimed for improving balance in parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Behav. Neurol. 2015 (1), 620674 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Glia protein aquaporin-4 regulates aversive motivation of Spatial memory in Morris water maze. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 19 (12), 937–944 (2013).

Wise, R. A. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5 (6), 483–494 (2004).

Zheng, G. et al. Beyond water channel: aquaporin-4 in adult neurogenesis. Neurochem. Int. 56 (5), 651–654 (2010).

Ewers, M. et al. Associative and motor learning in 12-month-old Transgenic APP + PS1 mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 27 (8), 1118–1128 (2006).

Tang, H., Shao, C. & He, J. Down-regulated expression of aquaporin-4 in the cerebellum after status epilepticus. Cogn. Neurodyn. 11, 183–188 (2017).

Vervoort, G. et al. Progression of postural control and gait deficits in parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait: A longitudinal study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 28, 73–79 (2016).

de Souza Fortaleza, A. C. et al. Dual task interference on postural sway, postural transitions and gait in people with parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait. Gait Posture. 56, 76–81 (2017).

Bekkers, E. M. et al. Adaptations to postural perturbations in patients with freezing of gait. Front. Neurol. 9, 377581 (2018).

Peterson, D. S., Dijkstra, B. W. & Horak, F. B. Postural motor learning in people with parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 263 (8), 1518–1529 (2016).

Bekkers, E. et al. Balancing between the two: are freezing of gait and postural instability in Parkinson’s disease connected? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.. 94, 113–125 (2018).

Korkusuz, S. et al. Effects of freezing of gait on balance in patients with parkinson’s disease. Neurol. Res. 45 (5), 407–414 (2023).

King, B. R. et al. Neural correlates of the age-related changes in motor sequence learning and motor adaptation in older adults. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 142 (2013).

Morrish, P., Sawle, G. & Brooks, D. An [18F] dopa–PET and clinical study of the rate of progression in parkinson’s disease. Brain 119 (2), 585–591 (1996).

Fasano, A. et al. Lesions causing freezing of gait localize to a cerebellar functional network. Ann. Neurol. 81 (1), 129–141 (2017).

Pasquini, J. et al. Clinical implications of early caudate dysfunction in parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 90 (10), 1098–1104 (2019).

Vandenbossche, J. et al. Impaired implicit sequence learning in parkinson’s disease patients with freezing of gait. Neuropsychology 27 (1), 28 (2013).

Olson, M., Lockhart, T. E. & Lieberman, A. Motor learning deficits in parkinson’s disease (PD) and their effect on training response in gait and balance: a narrative review. Front. Neurol. 10, 417264 (2019).

Doyon, J., Penhune, V. & Ungerleider, L. G. Distinct contribution of the cortico-striatal and cortico-cerebellar systems to motor skill learning. Neuropsychologia 41 (3), 252–262 (2003).

Sehm, B. et al. Structural brain plasticity in parkinson’s disease induced by balance training. Neurobiol. Aging. 35 (1), 232–239 (2014).

Ehgoetz Martens, K. A. et al. The functional network signature of heterogeneity in freezing of gait. Brain 141 (4), 1145–1160 (2018).

Schweder, P. M. et al. Connectivity of the pedunculopontine nucleus in parkinsonian freezing of gait. Neuroreport 21 (14), 914–916 (2010).

Chiviacowsky, S., Wulf, G. & Wally, R. An external focus of attention enhances balance learning in older adults. Gait Posture. 32 (4), 572–575 (2010).

Taubert, M. et al. Dynamic properties of learning-related grey and white matter changes in the adult human brain. Klinische Neurophysiologie. 41 (01), ID43 (2010).

Belluscio, V. et al. The association between prefrontal cortex activity and turning behavior in people with and without freezing of gait. Neuroscience 416, 168–176 (2019).

Bharti, K. et al. Abnormal cerebellar connectivity patterns in patients with parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait. Cerebellum 18, 298–308 (2019).

Kostić, V. et al. Pattern of brain tissue loss associated with freezing of gait in Parkinson disease. Neurology 78 (6), 409–416 (2012).

Hanoğlu, L. et al. Accelerated forgetting and verbal memory consolidation process in idiopathic nondement parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 70, 208–213 (2019).

Ghilardi, M. F. et al. The differential effect of PD and normal aging on early explicit sequence learning. Neurology 60 (8), 1313–1319 (2003).

Nieuwboer, A. et al. Motor learning in parkinson’s disease: limitations and potential for rehabilitation. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, S53–S58 (2009).

Dudai, Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55 (1), 51–86 (2004).

Sekeres, M. J., Moscovitch, M. & Winocur, G. Mechanisms of memory consolidation and transformation. Cogn. Neurosci. Memory Consolidation 17–44. (2017).

Dudai, Y. The restless engram: consolidations never end. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35 (1), 227–247 (2012).

Doyon, J. et al. Contributions of the basal ganglia and functionally related brain structures to motor learning. Behav. Brain. Res. 199 (1), 61–75 (2009).

Beeler, J. A., Petzinger, G. & Jakowec, M. W. The enemy within: propagation of aberrant corticostriatal learning to cortical function in parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 4, 134 (2013).

Cristini, J. et al. Motor memory consolidation deficits in parkinson’s disease: A systematic review with Meta-Analysis. J. Parkinson’s Disease, (Preprint) 1–28. (2023).

Jeon, M. T. et al. Emerging pathogenic role of peripheral blood factors following BBB disruption in neurodegenerative disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 68, 101333 (2021).

Hughes, A. J. et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 55 (3), 181–184 (1992).

Badrkhahan, S. Z. et al. Validity and Reliability of the Persian Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-P) Scale among Subjects with Parkinson’s Disease (Adult, 2019).

Montazeri, A. et al. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 1, 1–5 (2003).

De Jong-Gierveld, J. & Kamphuls, F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 9 (3), 289–299 (1985).

Quadt, L. et al. Brain-body interactions underlying the association of loneliness with mental and physical health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.. 116, 283–300 (2020).

Taghizadeh, G. et al. Clinimetrics of the freezing of gait questionnaire for Parkinson disease during the off state. Basic. Clin. Neurosci. 12 (1), 69 (2021).

Tomlinson, C. L. et al. Systematic review of Levodopa dose equivalency reporting in parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 25 (15), 2649–2653 (2010).

Brouwer, R. et al. Validation of the stabilometer balance test: bridging the gap between clinical and research based balance control assessments for stroke patients 67 77–84 (Gait & posture, 2019).

Wanner, P. et al. Acute exercise following skill practice promotes motor memory consolidation in parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 178, 107366 (2021).

Steib, S. et al. A single bout of aerobic exercise improves motor skill consolidation in parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 328 (2018).

Akizuki, K. & Ohashi, Y. Measurement of functional task difficulty during motor learning: what level of difficulty corresponds to the optimal challenge point? Hum. Mov. Sci. 43, 107–117 (2015).

Gheorghe, D. A., Panouillères, M. T. & Walsh, N. D. Psychosocial stress affects the acquisition of cerebellar-dependent sensorimotor adaptation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 92, 41–49 (2018).

Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual McGraw-Hill Education (UK) (Open University, 2013).

Schober, P., Boer, C. & Schwarte, L. A. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analgesia. 126 (5), 1763–1768 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the patients and caregivers for their collaboration. Funding for this research was provided by the research deputy of Iran University of Medical Sciences (grant number 27658).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [Mohammad Taghi Joghataei, Ghorban Taghizadeh]; Methodology: [Ghorban Taghizadeh, Hamed Montazeri], Data curation [Seyede Zohreh Jazaeri, Akram jamali], Formal analysis and investigation: [Ghorban Taghizadeh, Seyede Zohreh Jazaeri], Writing - original draft preparation: [Mohammad Taghi Joghataei, Seyede Zohreh Jazaeri]; Writing - review and editing: [Ghorban Taghizadeh, Akram Jamali, Hamed Montazeri], Supervision: [Mohammad Taghi Joghataei, Ghorban taghizade], Funding acquisition [Mohammad Taghi Joghataei]. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jazaeri, S.Z., Joghataei, M.T., Jamali, A. et al. The Role of Aquaporin-4 in Freezing of Gait and Dynamic Balance Learning in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci Rep 15, 31949 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15161-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15161-y