Abstract

Psoriasis (PsO) and Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are TNF-alpha-dependent immune-mediated inflammatory diseases where dendritic cells (DC) play a critical role in disease pathogenesis. Although TNF-alpha receptor 2 (TNFR2) has been implicated in the pathology of psoriatic diseases, its specific role in DC mediated responses remains unclear. To investigate the role of TNFR2 in DC in psoriatic disease, we utilized the mannan-oligosaccharide (MOS) model of PsA on mice with either TNFR2 intact or with DC-specific TNFR2 knockout (DC-TNFR2KO). We evaluated disease severity by assessing skin scaling, joint inflammation, serum cytokine profiles, and changes in the conventional type 1 dendritic cell (cDC1) population. A significant reduction in PsA-like skin scaling and joint inflammation was observed in DC-TNFR2KO mice. In control mice, MOS stimulated a robust increase in the cDC1 population, a response that was notably suppressed in the absence of DC-TNFR2. Furthermore, serum levels of key pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-12 (IL-12), TNF-alpha, IL-23 and IL-17 A were significantly diminished in DC-TNFR2KO mice following MOS exposure. Our findings provide compelling evidence that TNFR2 signaling in DC is instrumental in promoting PsA-like inflammation. These results highlight the potential of targeting the DC-TNFR2-pathways as a novel therapeutic strategy for PsA and related immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

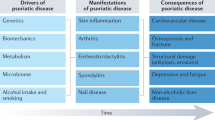

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a persistent inflammatory disorder that primarily impacts the skin and joints but may also involve the entheses leading to significant functional impairment and a diminished quality of life1,2,3,4. PsA, if untreated results in irreversible joint damage5,6. Although TNF-α neutralizing agents are the current first-line therapy for PsA, they are associated with an increased risk of opportunistic infections, reactivation of latent tuberculosis and malignancies which can hinder long-term use7,8,9. TNF-α functions through activating TNF-α receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2. Interestingly, preclinical studies in mice have shown that inhibition of TNFR1 rather than TNFR2 inhibition leads to these adverse effects10,11,12. In contrast, TNFR2 induces immune cell activation/proliferation and neoangiogenesis, all of which are hallmark features of psoriatic diseases13,14,15,16,17,18. Importantly, our previous work demonstrated that global TNFR2KO mice show reduced psoriasis-like inflammation concomitant with decreased DC activation pathways19. With the premise that TNFR2- targeted approach potentially will be effective with lower adverse effects compared to anti-TNF-α therapy, here we investigated whether depleting DC-TNFR2 can reduce PsA.

DC are a heterogeneous subset of antigen-presenting cells that link innate and adaptive immunity through antigen presentation- and cytokine-dependent activation of effector immune cells20. In humans, DC, are primarily classified into plasmacytoid DC (pDC), conventional DC-1 (cDC1), and cDC2. Both human and mouse cDCs exhibit distinct and overlapping function that are influenced by tissue localization and inflammatory state21,22. DC have been implicated in numerous inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including PsA23,24,25. Upon activation by pathogen- or damage-associated molecular pattern receptors, DCs secrete cytokines such as TNFα, IL-12, and IL-23, which are pivotal in both initiating and sustaining autoimmune inflammation in psoriatic disease21,23,26. These cytokines facilitate the differentiation of naïve T cells into the Th1 and Th17 subtypes which are crucial mediators of psoriatic diseases.

TNFR2 induces immune cell proliferation and activation13,15. Particularly, TNFR2’s role in regulating immunosuppressive T regulatory cells is well-documented27. Moreover, TNFR2 signaling enhances the polarization/proliferation of pathogenic T cells, including CD4 + and CD8 + T cells in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases14,16,28,29. TNFR2-positive cDC2 has also been implicated in the acquisition of pathological phenotypes in conditions such as asthma30. Despite the established involvement of dendritic cells in psoriatic diseases, the specific contribution of DC- expressed TNFR2 to psoriatic pathogenesis remains poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the role of DC-TNFR2 by comparing PsA-like inflammation in DC-TNFR2 knockout (DC-TNFR2KO) mice to that in TNFR2-intact mice, using the mannan-oligosaccharide (MOS) model31.

Results

PsA-like skin scaling and joint inflammation is reduced in DC-TNFR2KO

DC-TNFR2KO mice were generated by crossing TNFR2-floxed mice with CD11c-Cre mice. The mouse spleen contains ∼ 4% of dendritic cell population32. Flow cytometry analysis confirmed effective deletion of TNFR2 in dendritic cells: approximately 8.07% of CD11c⁺ splenocytes from TNFR2fl/fl control mice expressed TNFR2, compared to only 0.87% in DC-TNFR2KO mice (Fig. 1A). Following MOS-treatment, TNFR2-intact control mice exhibited profound scaling, thickness, and marked erythema (Fig. 1B, upper panel), whereas these clinical features were significantly attenuated in the DC-TNFR2KO mice (Fig. 1B, lower panel). The cumulative PASI score comprising erythema + scaling + skin thickness was significantly lower in DC-TNFR2KO mice at day 4 and day 6 post MOS treatment compared to control mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 1C). Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed that treatment had a significant effect on PASI scores (p = 0.0314, accounting for 44.49% of the total variation), whereas time (day) did not significantly influence the scores (p = 0.1001, 26.8% variation), indicating that the differences were primarily driven by the treatment. In addition to the skin findings, MOS–induced redness, swelling, and inflammation in the paws were reduced in the DC-TNFR2KO mice (Fig. 1D). Mean arthritis severity score (reflecting the clinical severity of paw arthritis) significantly decreased in DC-TNFR2KO mice on day 4 (p < 0.01) and day 6 (p < 0.001) as shown in Fig. 1E. Further, the loss of grip strength, an indicator of gross weakness of the paw due to inflammation, was partially restored in DC-TNFR2KO mice by day 6 (p < 0.05, Fig. 1F).

Reduced pathological phenotype in DC-TNFR2KO mice in the Mannan oligosaccharide (MOS)-induced PsA model. (A). Confirmation of TNFR2 depletion in spleen cells from DC-TNFR2KO (TNFR2fl/fl / CD11c-Cre) compared to control mice (TNFR2fl/fl) via FACS analysis. (B) Representative images of ear of TNFR2fl/fl (control) and DC-TNFR2KO mice treated with vehicle or MOS. (C) Cumulative PASI score (erythema + scaling + thickness) at baseline (day 0) and post MOS injection (day 2, 4 and 6). (D) Representative images of the arthritic phenotype (swelling and redness) and psoriasis-like skin lesions in the hind paws of control and DC-TNFR2KO mice. (E) Mean arthritis severity score of paws and, (F) Grip strength measurements over time. PASI and arthritis severity score were assessed in double blinded manner, with each score representing the mean of three independent scores per mouse (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as mean ± S.E (* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Histology analysis (Fig. 2A), followed by image quantification (Fig. 2B) revealed a robust increase in epidermal thickness in control mice upon MOS treatment (p < 0.001). We also found an increase in epidermal thickness in TNFR2KO mice with MOS (p < 0.001). However, the magnitude of epidermal thickness was lower in DC-TNFR2KO mice (32.18 ± 6.24 μm) compared to control mice (49.29 ± 6.33 μm) following MOS and was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Similarly, the increase in leukocyte infiltration, which can facilitate the epidermal thickening in psoriatic diseases was lower in DC-TNFR2KO mice compared to control mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 2C) upon MOS application.

Reduced epidermal thickness, leukocyte infiltration and cartilage content in DC-TNFR2KO mice following MOS treatment. (A) Representative H&E-stained ear tissue sections from TNFR2fl/fl (control) and DC-TNFR2KO mice with or without MOS treatment. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Epidermal thickness quantification. (C) Leukocyte infiltration, assessed in 3 high power fields (20X) per section by two independent blinded researchers. FOV: Field of view. (D) Representative safranin O-stained sections (cartilage staining) of distal interphalangeal joints. (E) Cartilage content quantification and, (F) Percentage cartilage loss following MOS treatment. Each dot represents the average of three independent sections per mouse (n = 6). Data are presented as means ± S.E, (**p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns = not significant). Tissue samples were collected on day 6 post-MOS.

Next, we investigated joint damage in control mice versus DC-TNFR2KO mice by assessing cartilage content in the joints using Safranin O staining (Fig. 2D). MOS treatment resulted in a significant reduction in cartilage of control mice (p < 0.001, Fig. 2E). Although there was a reduction in cartilage in DC-TNFR2KO joints with MOS treatment (p < 0.01), the effect was less. Specifically, by day 6 post-treatment, control mice exhibited a 47.70% decrease in cartilage, compared to a 29.98% reduction in DC-TNFR2KO mice (Fig. 2F).

TNFR2 depletion attenuated the increase of conventional DC1 (cDC1) population in mice with PsA-like inflammation

To investigate the effect of TNFR2 depletion on relative abundance of DC subtypes, we compared the percentage of cDC1, cDC2 and pDC population in the splenocytes of control mice and DC-TNFR2KO in the presence or absence of MOS treatment. Flow cytometry analyses (Fig. 3A) showed that cDC1 cell population increased significantly in control mice in response to MOS (7.34 ± 1.55% to 14.06 ± 2.21%, p < 0.001), whereas this effect was not observed in DC-TNFR2KO mice (Fig. 3B). The percentage difference in cDC1 population between control mice and DC-TNFR2KO with MOS treatment was also significant (p < 0.01, Fig. 3B).

Reduced expansion of conventional DC1 (cDC1) population in DC-TNFR2KO mice following MOS treatment. Flowcytometry plots of cDC1 and cDC2 populations in spleen cells from control and DC-TNFR2KO mice ± MOS. (A) representative figure showing the percentage of cDC1 and cDC2 cells among the splenocytes isolated from control or DC-TNFR2KO mice ± MOS. (B) Quantification of cDC1%. (C) Quantification of cDC2%. Data (n = 5 per group) represent means ± S.E, (D) (a) Quantification of CD80 expression in cDC1 (n = 3 per group) mean ± S.E.M. (b) Histogram of CD86 expression in cDC1, gMFI; Geometric Mean Fluorescent Intensity. (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns = not significant). Tissue samples were collected on day 6 post-MOS.

.Conversely, cDC2 cell population, showed a decreasing trend with MOS treatment in both control and DC-TNFR2KO mice, but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3C). Although there was an upward trend in plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) population in both control and DC-TNFR2KO mice with MOS, it also did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 1). The FACS strategy for measuring cDC1, cDC2 and pDC is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

To determine TNFR2’s role cDC1 activation, we measured activation markers CD80 and CD86. We found that there was no change in CD80 expression in cDC1 isolated from either control mice or DC-TNFR2KO mice with or without MOS (Fig. 3Da & b). The CD86 expression could only be assessed in a single experimental replicate, which also demonstrated no apparent difference between groups, are now presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

The activated DC can produce IL-12 and TNF-α, which can facilitate the polarization of naïve Th cells into CD4 + effector T cells including Th1 andTh17 cells as well as CD8 + T cells16,20,26. In agreement, we found an increase of DC product, IL-12 (39.61 ± 7.09 pg/ml to 104.10 ± 9.37 pg/ml, p < 0.001) in the serum of mice treated with MOS, but not in DC-TNFR2KO mice (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, we also found an increase in TNF-α in both control mice (25.93 ± 2.39 pg/ml to 65.31 ± 13.34 pg/ml, p < 0.001) and DC-TNFR2KO mice (30.38 ± 4.46 pg/ml to 40.61 ± 7.52 pg/ml, p < 0.05). However, the increase of TNF-α in DC-TNFR2KO was less pronounced and the difference between the treated groups were statistically significant (p < 0.01). Similarly, IL-23 level in the serum was elevated (from 24.5 ± 6.6 pg/ml to 93.4 ± 12.1pg/ml, p < 0.001) whereas in DC-TNFR2KO mice the induction was reduced (from 21.5 pg/ml to 45.8 pg/ml, p < 0.05), upon MOS treatment (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the serum level of Th17 product IL-17 A was also reduced in DC-TNFR2KO mice compared to control mice. As shown in Fig. 4D, the IL-17 A was undetectable in untreated, control mice and DC-TNFR2KO mice (< 5pg/ml) and it increased robustly in control mice with MOS (76.7 ± 9.2 pg/ml, p < 0.001), whereas the increase was less prominent in DC-TNFR2KO mice (28.56 ± 5.9 pg/ml, p < 0.01).

Reduced circulating cytokine levels in DC-TNFR2KO mice following MOS treatment. Serum cytokine levels were measured by ELISA: (A) IL-12 (n = 4 per group) and (B) TNF-α (n = 5 per group), (C) IL-23 (n = 4 per group), and (D) IL-17 A (n = 4 per group), Data represent means ± S.E (*p < 0.05 **< 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns = not significant). Tissue samples were collected on day 6 post-MOS.

Discussion

Although various biological agents have recently emerged for the treatment of psoriatic diseases, anti-TNF agents remain the first-line treatment for PsA33,34. These agents neutralize TNF-α thus preventing activation of both TNFR1 and TNFR235. However, preclinical studies show that the adverse effects associated with long-term use of anti-TNF agents are primarily attributed to TNFR1 inhibition12,36. Based on this background information, our results demonstrating TNFR2 inactivation in DCs effectively reduces PsA-like inflammation carry significant clinical implications. This suggests that targeting TNFR2 or it’s downstream signaling pathways in DC may offer a more targeted therapeutic option with fewer adverse effects compared to conventional anti-TNF drugs, which inhibit the activity of both TNFR1 and TNFR2.

DCs are among the most effective antigen-presenting cells, effectively bridging the gap between innate and adaptive immune responses22,37. In psoriatic diseases, TNFα activates DCs, which in turn produce cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-23, promoting the polarization of naïve Th cells and downstream effector responses in the skin and joints20,38. Our study found that deletion of TNFR2 in DCs significantly reduced skin and joint inflammation in the murine model of PsA induced by MOS. Although we observed a notable decrease in cartilage content in the paw joints of DC-TNFR2KO mice, the overall joint phenotype was mild in this mouse model. This was expected, as MOS induces robust joint disease only when reactive oxygen species (ROS) are depleted31. By designing our study to minimize ROS-sensitive macrophage responses (given that CD11c-Cre may also target macrophages), we were able to more precisely delineate the role of dendritic cells in disease pathology.

While our histological analysis focused on cartilage-loss as a measurable outcome of joint damage, we acknowledge that synovial and peri-tendon inflammation (enthesitis) are also key contributors to joint dysfunction and loss of grip strength in PsA, which warrant further investigation. Similarly, while our study showed reduced circulating IL-12, IL-23, IL-17 A and TNFα in DC-TNFR2KO mice compared to control mice upon MOS treatment, we did not directly assess intracellular cytokine production within specific dendritic cell subsets. Future studies using intracellular staining approaches are needed to demonstrate conclusively that cDC1 is the primary source of these cytokines.

TNFR2 promotes proliferation of pathogenic T cells, including CD4 + and CD8 + T cells in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases14,16,29. However, the role of TNFR2 in DC function or DC expansion, particularly in the case of cDCs during pathological conditions is not clear. One study, implicated TNFR2’s involvement in human cDC2 maturation, but not cDC1 maturation, in the lung in response to adjuvants, in mice28. We did not see a difference in the activation markers the absence of TNFR2 indicates TNFR2 modulates cDC1 mediated inflammation in this model likely through effects on cell abundance rather than activation status.

While both cDC1 and a subset of cDC2 express TNFR2, we found that only cDC1 expansion is significantly impaired in the absence of TNFR2 in our PsA mouse model. This could be attributed several factors including potential differences in the level of TNFR2 expression between cDC subsets, divergence in downstream TNFR2 signaling pathways, variations in metabolic programming, or distinct responsiveness to MOS-driven stimuli20,25,28,39,40. It is also possible that cDC2 expansion is regulated through additional compensatory pathways that do not rely on TNFR2 signaling.

The cDC1 are primarily responsible for priming CD8 + T cells by cross-presentation of antigens in conjunction with MHC class I41but cDC1 can also activate CD4 + Th1 cells42 and both CD8 + T and CD4 + cells can promote psoriatic diseases43. Further studies are needed to identify the T effector cells that are activated by TNFR2-positive cDC1 in psoriatic disease. Considering the functional overlap between murine and human cDC139, strategies aimed at modulating cDC1 function or inducing their tolerogenicity may represent a novel approach to mitigating psoriatic disease. More targeted approaches are needed to decipher the relative importance of DC subtypes in the pathogenesis of psoriatic diseases.

In summary, our study reveals a previously uncharacterized role of TNFR2/cDC1-axis in the pathogenesis of PsA. Our findings suggest that selectively targeting TNFR2 pathways in cDC1 while preserving TNFR1 mediated host defense, may ameliorate PsA effectively with potentially fewer adverse effects compared to conventional anti-TNF agents.

Materials and methods

Animals and genotyping

The animal-related experiments were approved by Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. All experiments were performed in accordance with committee’s guidelines and regulations which follow the Animal Welfare Act and Public Health Services policies.

All mice used were maintained on a C57BL/6 genetic background, kept under specific pathogen-free conditions, and provided with food and water ad libitum at the BRU facility. Experiments were performed on 8-to 10-weeks-old gender-matched mice. TNFR2-floxed mice (TNFR2fl/fl) were crossed with CD11c-Cre transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory (Strain #008068) to delete TNFR2 from dendritic cells (TNFR2fl/fl/ CD11c-CRE) mice. Prior to selecting TNFR2fl/fl mice as controls for our experiments, we compared them directly with Cre+ mice and found no discernible phenotypic differences in gross morphology or dendritic cell populations, either at baseline or following MOS treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4). Based on this, we used TNFR2fl/fl mice as the control group for the current study. TNFR2fl/fl mice were obtained from Dr. Roberta Brambilla (The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, Dept. Neurological Surgery, and the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, FL 33136, USA). Genotyping was performed on chromosomal DNA isolated from toe clips. The genotyping of the loxP-flanked (floxed) TNFR2 transgenic animals was performed using the following primers: 5’- TTG GGT CTA GAG GTG GCG CAG C-3’ and 5’-GGC CAG GAA GTG GGT TAC TTT AGG GC-3’ resulting in products of 410 bp for wildtype and 578 bp for the floxed allele. The following primers were used to detect the transgenic Cre expression: 5’-ACT TGG CAG CTG TCT CCA AG’-3’, 5’- GCG AAC ATC TTC AGG TTC TG-3’, 5- CAA ATG TTG CTT GTC TGG TG-3’ and 5’- GTC AGT CGA GTG CAC AGT TT-3’ generating products 313 bp for Cre allele and 200 bp as internal positive control.

Mannan oligosaccharide (MOS)-induced PsA model in mice

MOS (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., USA) was dissolved in PBS and injected intraperitoneally (IP) at a dose of 800 mg/kg body weight on day 0. The ear and paw thickness were measured on alternate days using an electronic digital dial thickness gauge (0-0.4”/10 mm caliper, 0.01 mm resolution, ± 0.03 mm accuracy). Inflammation in peripheral joints was assessed every two days, following the method outlined previously31. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) graded the severity of psoriatic skin lesions, which is based on the parameters of skin erythema, scaling, and thickness. PASI was scored on a scale from 0 to 4 in a blinded fashion and was recorded on days 0,2,4, and 6. The grip strength was measured using a grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments, USA).

Histology evaluation

Mice from each group were sacrificed after anesthetizing with Ketamine/Xylazine (100 mg/15 mg per kg body weight) followed by cervical dislocation. Paws were decalcified in TCA (A11156.30, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Decalcified paws and skin tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (5705, Epredia, USA) and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were stained with H&E and/or safranin O, and epidermal thickness, leukocyte infiltration, and cartilage content were assessed.

Flow cytometry analysis

CD11c+ cells from spleen underwent flow cytometry analysis. To ensure optimal recovery and purity of CD11c+ cells, spleen was initially subjected to enzymatic digestion using a spleen dissociation kit (130-095-926, Miltenyi Biotec, USA). The red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysing buffer44. The Cd11c + cells were isolated through magnetic separation using a negative selection kit (480098, Biolegend, USA).

The cells were then counted and stained with Live/dead fixable dye (L34960, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). After incubation with Fc block solution (550270, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) samples were stained with extracellular antigen-specific antibodies, for TNFR2/p75 (113406, BioLegend, USA), CD11c (117357, BioLegend, USA), CD11b (101228, BioLegend, USA), MHCII (107608, BioLegend, USA), CD8 (560778, BD biosciences, USA), CD45R (564662, BD biosciences, USA), CD80 (11-0801-81, Invitrogen, USA), CD86 (105036, BioLegend, USA), and LY6C (128044 BioLegend, USA); for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. The cells were then washed and analyzed using BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The workstation is managed by FACSDiva software, version 10 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). The data were analyzed using FlowJo v 10.8.1 (BD, 385 Williamson Way Ashland, OR 97520, USA).

Cytokine analysis

Mice were sacrificed by cardiac puncture on day 6 of MOS injection and blood was collected in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes containing heparin. Following centrifugation plasma was collected and stored at − 80 °C before cytokine analysis by ELISA. ELISA kits for IL-12p70 (BMS6004), and TNFα (BMS607-3) were purchased from Invitrogen, Thermos Fisher Scientific USA. ELISA kits for IL-23 and IL-17 A are purchased from R&D systems, catalog #M2300 and #M1700, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0(IBM, SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA) and GraphPad Prism Version 8.0.2(263) (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA. https://www.graphpad.com). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E and were assessed using two-way ANOVA or Student’s t-test. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In figures, asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001).

Data availability

All relevant data for this article is included, and any further inquiry including the protocol used can be made to the corresponding authors.

References

Ogdie, A. & Weiss, P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 41, 545–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2015.07.001 (2015).

Veale, D. J. & Fearon, U. The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Lancet 391, 2273–2284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30830-4 (2018).

Surace, A. E. A. & Hedrich, C. M. The role of epigenetics in autoimmune/inflammatory disease. Front. Immunol. 10, 1525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01525 (2019).

Carvalho, A. L. & Hedrich, C. M. The molecular pathophysiology of psoriatic Arthritis-The complex interplay between genetic predisposition, epigenetics factors, and the Microbiome. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 662047. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.662047 (2021).

Ritchlin, C. T., Colbert, R. A. & Gladman, D. D. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl. J. Med. 376, 957–970. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1505557 (2017).

Tenazinha, C., Barros, R., Fonseca, J. E. & Vieira-Sousa, E. Histopathology of psoriatic arthritis Synovium-A narrative review. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 860813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.860813 (2022).

Yasui, K. Immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the risk of biologic anti-TNF-alpha reagents. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 12, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-45 (2014).

Li, B. et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with Myelodysplasia-Related changes in a patient with crohn’s disease treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Case Rep. Oncol. 11, 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1159/000491573 (2018).

Kireev, F. D., Lopatnikova, J. A., Alshevskaya, A. A. & Sennikov, S. V. Role of tumor necrosis factor in tuberculosis. Biomolecules 15, 8563. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15050709 (2025).

Peschon, J. J. et al. TNF receptor-deficient mice reveal divergent roles for p55 and p75 in several models of inflammation. J. Immunol. 160, 943–952 (1998).

Rothe, J. et al. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature 364, 798–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/364798a0 (1993).

Wroblewski, R. et al. Opposing role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling in T cell-mediated hepatitis and bacterial infection in mice. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28551 (2016).

Tartaglia, L. A. et al. The two different receptors for tumor necrosis factor mediate distinct cellular responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 88, 9292–9296 (1991).

Ye, L. L., Wei, X. S., Zhang, M., Niu, Y. R. & Zhou, Q. The significance of tumor necrosis factor receptor type II in CD8(+) regulatory T cells and CD8(+) effector T cells. Front. Immunol. 9, 583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00583 (2018).

Khan, A. U. H. et al. The TNFalpha/TNFR2 axis mediates natural killer cell proliferation by promoting aerobic Glycolysis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 20, 1140–1155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-023-01071-4 (2023).

Alam, M. S. et al. TNF plays a crucial role in inflammation by signaling via T cell TNFR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118, 745. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2109972118 (2021).

Goukassian, D. A. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor p75 is required in ischemia-induced neovascularization. Circulation 115, 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.647255 (2007).

Li, S. et al. Low-dose TNF-alpha promotes angiogenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via TNFR2/Akt/mTOR axis. Oral Dis. 30, 3004–3017. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.14802 (2024).

Chandrasekharan, U. M. et al. TNFR2 depletion reduces psoriatic inflammation in mice by downregulating specific dendritic cell populations in lymph nodes and inhibiting IL-23/IL-17 pathways. J. Invest. Dermatol. 142, 2159–2172e2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2021.12.036 (2022).

Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M., Cardoso, A., Minutti, C. M., Pereira da Costa, M. & Reis e sousa, C. Dendritic cells revisited. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 39, 131–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-061020-053707 (2021).

Granot, T. et al. Dendritic cells display subset and Tissue-Specific maturation dynamics over human life. Immunity 46, 504–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.019 (2017).

Collin, M. & Bigley, V. Human dendritic cell subsets: an update. Immunology 154, 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12888 (2018).

Haniffa, M., Gunawan, M. & Jardine, L. Human skin dendritic cells in health and disease. J. Dermatol. Sci. 77, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.08.012 (2015).

Marzaioli, V. et al. CD209/CD14(+) dendritic cells characterization in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis patients: activation, synovial infiltration, and therapeutic targeting. Front. Immunol. 12, 722349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.722349 (2021).

Yu, J. et al. EDIL3 alleviates Mannan-induced psoriatic arthritis by slowing the intracellular Glycolysis process in mononuclear-derived dendritic cells. Inflammation https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-024-02134-y (2024).

Nestle, F. O., Di Meglio, P., Qin, J. Z. & Nickoloff, B. J. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2622 (2009).

Zou, H., Li, R., Hu, H., Hu, Y. & Chen, X. Modulation of regulatory T cell activity by TNF receptor type II-Targeting Pharmacological agents. Front. Immunol. 9, 594. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00594 (2018).

Mansouri, S. et al. Immature lung TNFR2(-) conventional DC 2 subpopulation activates modcs to promote Cyclic di-GMP mucosal adjuvant responses in vivo. Mucosal Immunol. 12, 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-018-0098-0 (2019).

Mehta, A. K., Gracias, D. T. & Croft, M. TNF activity and T cells. Cytokine 101, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.003 (2018).

Mansouri, S. et al. In vivo reprogramming of pathogenic lung TNFR2(+) cDC2s by IFNbeta inhibits HDM-induced asthma. Sci. Immunol. 6, 856. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abi8472 (2021).

Khmaladze, I. et al. Mannan induces ROS-regulated, IL-17A-dependent psoriasis arthritis-like disease in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, E3669–3678. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1405798111 (2014).

Hensel, J. A., Khattar, V., Ashton, R. & Ponnazhagan, S. Characterization of immune cell subtypes in three commonly used mouse strains reveals gender and strain-specific variations. Lab. Invest. 99, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-018-0137-1 (2019).

Coates, L. C. et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 18, 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-022-00798-0 (2022).

Singh, J. A. et al. Special article: 2018 American college of rheumatology/national psoriasis foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 71, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40726 (2019).

Sedger, L. M. & McDermott, M. F. TNF and TNF-receptors: from mediators of cell death and inflammation to therapeutic giants - past, present and future. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 25, 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.016 (2014).

Senaldi, G. et al. Corynebacterium parvum- and Mycobacterium Bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin-induced granuloma formation is inhibited in TNF receptor I (TNF-RI) knockout mice and by treatment with soluble TNF-RI. J. Immunol. 157, 5022–5026 (1996).

Kamata, M. & Tada, Y. Dendritic cells and macrophages in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 13, 941071. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.941071 (2022).

Blanco, P., Palucka, A. K., Pascual, V. & Banchereau, J. Dendritic cells and cytokines in human inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 19, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.10.004 (2008).

Robbins, S. H. et al. Novel insights into the relationships between dendritic cell subsets in human and mouse revealed by genome-wide expression profiling. Genome Biol. 9, R17. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r17 (2008).

Gallo, P. M. & Gallucci, S. The dendritic cell response to classic, emerging, and homeostatic danger signals. Implications for autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 4, 138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2013.00138 (2013).

Theisen, D. & Murphy, K. The role of cDC1s in vivo: CD8 T cell priming through cross-presentation. F1000Res 6, 98. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.9997.1 (2017).

Inui, H. et al. XCR1(+) conventional dendritic cell-induced CD4(+) T helper 1 cell activation exacerbates cardiac remodeling after ischemic myocardial injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 176, 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2023.01.011 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. The roles of T cells in psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1081256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1081256 (2023).

Brown, W. E., Hu, J. C. & Athanasiou, K. A. Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium Lysing buffer treatment of fully differentiated cells increases cell purity and resulting neotissue functional properties. Tissue Eng. Part. C Methods. 22, 895–903. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEC.2016.0184 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of our Technologist, Vincent Del Signore, BS for maintaining mouse colony used in this study.

Funding

This work is supported by NIH Grant R01AR075777 to M.E.H & U.M.C. National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Bridge-Grant: NPF1808UC to U.M.C. & M.E.H. Early Research Grant from National Psoriasis Foundation to R.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E.H, U.MC and R.K conceptualized and designed the experimental plan, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. R.K, J.L and J.E.H performed the experiments and prepared figures, R.B. provided technical help and valuable reagents and provided critical discussions. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, R., Lin, J., Harvey, J.E. et al. Targeting dendritic cell-specific TNFR2 improves skin and joint inflammation in a murine model of psoriatic arthritis. Sci Rep 15, 31574 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15175-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15175-6