Abstract

In the current study transparent solid ion conducting biopolymer blend electrolytes consisting of chitosan/cold water fish skin gelatin were prepared utilizing casting methodology. Ammonium thiocyanate (NH4SCN) salt as a source of proton provider was added to the polymer blends. The ion conductor films were characterized by various methods including XRD, FTIR and EIS. The area under crystalline and amorphous peaks in the XRD patterns were determined and used to estimate the degree of crystallinity. The bands of FTIR pattern associated with anions of the added salt was deconvoluted to determine the fractions of free ions, ion aggregate and ion triplets. Comprehensive investigations of the electrical properties, including DC and AC conductivity, dielectric constant, dielectric loss and electric modulus, were studied to understand the ion conduction mechanism. The ion transport parameters obtained from both EIS and FTIR approach were in good agreement. The shift of peaks to higher frequencies in the loss tangent spectra indicated enhanced ion mobility at shorter time scales. The observation of relaxation peaks in the electric modulus (M’’) spectra, which are absent in the dielectric loss (ε’’) spectra, underscores the effectiveness of the modulus formalism in suppressing the contribution of electrode polarization and emphasizing bulk relaxation. AC conductivity spectra revealed three distinct conduction regimes, while the Argand plots provided insights into the ion relaxation dynamics within the current solid biopolymer electrolytes. The highest room-temperature ionic conductivity of 1.19 × 10−5 S/cm was achieved at 40 wt% NH4SCN, attributed to the optimal balance between free ion concentration and polymer segmental mobility, as revealed by FTIR and EIS analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing environmental concerns and the global demand for sustainable energy solutions, have driven researchers to explore sustainable alternatives to conventional materials. Plastic pollution and substantial organic waste from the fish industry have emerged as major ecological challenges1,2. However, these waste materials, particularly fish-derived by-products, offer valuable sources of biodegradable polymers like gelatin and chitosan, which are increasingly investigated for use in eco-friendly energy systems such as polymer electrolytes3,4. Liquid electrolytes, favored in batteries and supercapacitors for their low bulk resistance and high ionic conductivity, however, problems like toxic and corrosive leaks restrict its stability and safety5. Solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) have emerged as a safer, more compatible alternative for modern electronic devices, distinguished by their low cost, light weight, flexibility, thermal stability, and user-friendly nature6. Solid polymer blend electrolytes, combining natural and synthetic polymers, are gaining consideration in energy storage applications. Despite being non-biodegradable, synthetic polymers like polyvinyl chloride, polyethylene, polymethylmethacrylate, poly-acrylonitrile, and polycarbonate remain widely used7. This has contributed to the growing electronic waste problem8. Recent efforts have focused on developing biodegradable and bio-based polymers to mitigate environmental impact6. Biopolymer-based SPEs, valued for their non-toxicity, renewability, biodegradability, and low cost, are readily derived from plant and animal sources and applied in batteries, supercapacitors, and dye-sensitized solar cells7,9. Various biodegradable natural polymers, including cellulose acetate10, starch11, pectin9, carboxymethyl cellulose12, and chitosan13, have been utilized. There have also been reports of bio-polymer electrolytes based on agar14, and gelatin15.

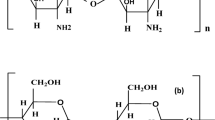

Chitosan (CS), a biopolymer derived from the N-deacetylation of chitin has gained significant attention in materials research due to its unique chemical functionality and versatile applications. Due to its high nitrogen content, which sets it apart from other materials, CS is considered as a preferred raw polymer for SPE system due to its biodegradable, biocompatible and possesses excellent adsorption capability. CS is an N-deacetylated form derived from chitin, a naturally arising biopolymer found in the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans. Structurally, its functional hydroxyl and amine groups enable extensive chemical modification and interaction, including the ability to form non-covalent complexes with other polyelectrolytes16. Critical parameters such as the deacetylation degree, the functional groups distribution across the polymer backbone, and macromolecular conformation significantly influence its complexation behavior and performance in advanced materials systems. Despite its notable properties, CS still requires significant improvements to address its low ionic conductivity and the limitations on ion transport imposed by its semicrystalline nature. On the other hand, gelatin, a naturally occurring polymer, is usually derived from the hydrolysis of collagen, can also be sourced from fish industry waste providing a sustainable method of waste management17. The primary limitations of this bio-based polymer are its low mechanical strength due to its hydrophilic nature, and minimal ionic conductivity at ambient temperature. Chitosan (CS) and cold-water fish skin gelatin (FSG) exhibit comparable semicrystalline structures, offering appropriate flexibility and morphology for functional applications. Figure S1 illustrates the extraction of gelatin via collagen hydrolysis and the conversion of chitin into CS through deacetylation.

The structural and electrical properties of polymer electrolytes critically influence electrochemical device performance. Careful selection of the polymer matrix and salt, along with strategies like polymer blending, has enabled the development of high-conductivity electrolytes with diverse advantageous properties18,19. Blending introduces additional active sites that enhance the electrical and structural characteristics of the host polymer, thereby facilitating chain segmental motion and promoting ion migration20. The appropriate select of a cross-linker is crucial for establishing strong chemical bonds, thereby enhancing the stability and functionality of the blend. In blending CS and cold-water FSG, their functional groups, including hydroxyl (O–H), amine (-NH2, -NH3+), and carboxylic (-COOH/-COO−), play a vital role. These functional groups engage in electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding, significantly improving the compatibility and cohesive integration of the polymer matrix, leading to enhanced electrical conductivity, mechanical properties, and thermal stability21. Recent studies have highlighted the exceptional film-forming capabilities of CS when combined with FSG21,22,23,24. This blend produces a biodegradable and biocompatible material that demonstrates improved bioactivity and cell adhesion properties, making it highly suitable for various applications. In addition to having a suitable polymeric host medium for SPEs, selecting a salt compatible with the polymer host is crucial to enhance ionic conductivity, mechanical strength, and chemical stability25. These materials must exhibit key properties such as low toxicity, high thermal and electrochemical stability, and resistance to moisture absorption. Ionic conductivity of electrolytes depends on both ion concentration and their mobility, which can be enhanced by salt addition. The salt’s lattice energy plays a critical role, as lower lattice energy facilitates greater ion dissociation, thereby increasing the number of mobile charge carriers26. Lattice energy is primarily influenced by ionic charge and radius; it increases with higher charges and smaller ionic sizes27.

A review of the literature indicates that bio-based polymer electrolytes containing ammonium salts are relatively scarce. To develop a novel polymer electrolyte with enhanced ionic conductivity, dopants such as SCN−, I−, CF3SO3−, ClO4−, and ammonium salts with large anions and low lattice energy could be utilized. The linear anion SCN− is known to form complexes with cations such as NH4+, Li+, Na+, and K+ through coordination to either the nitrogen or sulfur atom. Ammonium salts have been shown to efficiently donate protons, as one of the four protons associated with the nitrogen atom is weakly bound. This weakly bound proton can migrate throughout the polymer network. Optimizing an electrolyte for a given application requires considering the salt’s lattice energy, as lower lattice energy promotes faster ion association. Reports indicate that a lattice energy lower than 600 kJ/mol markedly impairs DC conductivity. In their study, Brza et al. utilized NH4BF4, which has a low lattice energy of 582 kJ/mol, as an ion provider for polymer electrolyte systems; however, this resulted in a low DC conductivity of 7.932 × 10−7 S/cm, making it unsuitable for applications27. Conversely, salts with high lattice energy exhibit limited dissociation into free cations and anions, which also leads to decreased overall ionic conductivity due to a limited concentration of free ion carriers. Therefore, it is essential to select salts with medium lattice energy, such as NH4SCN (605 kJ/mol), NH4I (634 kJ/mol), NH4NO3 (646 kJ/mol), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) (698 kJ/mol), and ammonium bromide (NH4Br) (665 kJ/mol)27. Although substantial research has been conducted on biodegradable polymer electrolytes, a comprehensive literature review reveals that there has not been any investigation into the efficacy of SPEs based on CS and FSG doped with NH4SCN.

The present work focuses on the development and characterization of natural bio-polymer electrolytes as sustainable alternatives to synthetic polymers. The goal is to use renewable, biodegradable materials to mitigate the environmental issues associated with plastic and aquaculture waste. To this end, energy storage system used a blended bio-polymer electrolyte made of CS and cold-water FSG. This mixed polymer electrolyte has several noteworthy features, including cost-effectiveness, abundance, strong film-forming capability, and compatibility with various salts. In addition, this study focuses on investigating the structural and electrical characteristics of a composite blend of CS and FSG polymers that have been doped with varying concentrations of NH4SCN. Furthermore, the study will investigate the relationship between ionic motion and the dynamics of polymer chains, which is an important point of interest in polymer electrolytes. XRD and FTIR techniques also used to analyze the structural and complexation behavior of the system. In addition, the ion conduction mechanism will be correlated with the dielectric properties and relaxation processes, which will be examined through EIS. A comprehensive evaluation will identify key parameters governing ion transport and conductivity enhancement. This study demonstrates that detailed analysis of both structural and electrical properties is essential to understanding ion dynamics in polymer electrolytes.

Materials and methodology

Materials

The research involved a host matrix made from chitosan (CS) from shrimp shell and gelatin obtained from the skin of cold-water fish (FSG). The CS used has an average molecular weight of about 310,000 g/mol and a degree of deacetylation of more than 75%. In addition, the FSG has an average molecular weight of about 60,000 g/mol. Both biopolymers used in this research were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Ammonium thiocyanate (NH4SCN), with a molecular weight of 76.13 g/mol, and acetic acid (CH3COOH) with a molecular weight of 60.05 g/mol, were supplied from Merck. Throughout the experiment, glacial and distilled water were used as the solvent, ensuring a high degree of purity and reducing the possibility of impurities that could influence the results. Moreover, every compound employed in the experiment was utilized in its original, unprocessed form without any purification.

Polymer electrolyte Preparation

A biodegradable polymer blend was prepared using the traditional casting method. Various weight percentages of chitosan were dissolved in 80 ml of 1% acetic acid to determine the most suitable amorphous blend system for the synthesis of SPEs. To achieve a homogeneous CS solution, the mixture was agitated continuously for 24 h. Subsequently, the solution was left to rest for an entire day, covered with aluminum foil, resulting in a transparent and clear solution. As detailed in Tables 1 and 80 ml of distilled water was utilized to dissolve FSG at varying concentrations (20, 40, 60, and 80 wt%) from cold-water. This mixture was stirred continuously for half an hour at ambient temperature. To create the polymer blend solutions, the CS: FSG solutions were then combined and agitated for an additional two hours. The resulting mixture was cast into clean, dry Petri dishes to form films. After allowing the samples to remain at room temperature for twenty-one days, the solvent evaporated, resulting in solvent-free polymer blend films. The schematic illustration for the prepared CS: FSG polymer blend systems was shown in Fig. 1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was employed to investigate the structural characteristics of the CS: FSG biopolymer films. Among the studied compositions, the CSFSG3 blend was identified as the optimal formulation based on its diffraction pattern. The results indicated that the CSFSG3 film exhibited the highest degree of amorphous character, suggesting its suitability as an efficient host matrix for SPE development.

Following that, six distinct SPE films were prepared utilizing biopolymer blends. Initially, 280 milliliters of 1% acetic acid were used to dissolve 4.2 g of CS, and the solution was stirred continuously for twenty-four hours at ambient temperature. In a separate step, 2.8 g of cold-water FSG was dissolved in 280 mL of distilled water at room-temperature and stirred for one hour. After this, the solutions of CS and cold-water FSG were combined and stirred continuously at room temperature for 3 h. Subsequently, the solution was covered with aluminum foil and allowed to sit for a full day, resulting in a clear, transparent solution. Next, six samples of the CS: FSG blend were transferred into 80 mL beakers. Each beaker was loaded with varying concentrations of NH4SCN salt, specifically 8%, 16%, 24%, 32%, 40%, and 48% by weight. To ensure complete dissolution of the salt, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for three hours. The resulting mixtures were designated as CGNSCN0, CGNSCN8, CGNSCN16, CGNSCN24, CGNSCN32, CGNSCN40, and CGNSCN48, corresponding to salt loadings of 0%, 8%, 16%, 24%, 32%, 40%, and 48%, as summarized in Table 2. After that the solutions were allowed to settle for an additional two hours to release any trapped air bubbles. Then, the solutions were poured onto Teflon Petri plates and left at ambient temperature for 3 weeks to allow complete solvent evaporation and the SPE film to form. After the film formation, the films were carefully peeled off and placed in a blue silica gel desiccator to facilitate additional drying and ensure proper storage. Figure 2 presents a schematic representation of the main stages of the SPE preparation, along with images taken during the preparation process in the laboratory.

Characterization of electrolytes

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) study

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to study the bonding interactions and structural features of the prepared SPE films. A Bruker Tensor-27 spectrometer was used to record FTIR spectra from the prepared films, capturing data with a precision of 1 cm⁻¹ across a wavelength range of 400 to 4000 cm⁻¹. The analysis employed a Gaussian-Lorentzian function to examine definite peaks, utilizing a deconvolution method to resolve overlapping peaks and identify various ion transport properties.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) investigation

The crystallographic structure of the prepared SPE films was investigated using data obtained from an XRD device model ADX 2700 pro diffractometer under ambient temperature conditions. The samples were subjected to CuKα radiation with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å, operating at a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 30 mA. Measurements were carried out with a step size of 0.1°, covering a glancing angle range of 10° ≤ 2𝜃 ≤ 80°.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) study

To evaluate the overall electrical performance of the SPEs, it is crucial to investigate its electrochemical properties and examine the electrical behavior at the interface between the electrodes and the electrolyte. Complex impedance spectroscopy is a non-destructive technique that can provide this information. For the EIS measurements conducted in the frequency range of 100 Hz to 2 MHz, we used a computer-synchronized Precision Keysight LCR Meter. An applied voltage amplitude of 10 mV was utilized in the measurements. The prepared SPEs were cut into discs with a surface area of 2 cm² and placed between two stainless steel electrodes under spring-loaded to ensure good electrical contact. Stainless steel electrodes are commonly used with polymer electrolytes due to their chemical stability and inertness. The experimental setup for conducting the EIS investigation is illustrated in the supplementary materials Figure S2.

The electrical characteristics of the SPEs were investigated using the collected data, and the ionic conductivity (\(\:{\sigma\:}_{dc}\)) was calculated as per the corresponding equation28.

where \(\:d\) denotes the film’s thickness measured in centimeters, \(\:A\) represents its area in square centimeters, and \(\:{R}_{b}\) signifies its bulk resistance in ohms. The value of \(\:{R}_{b}\) can be obtained by identifying the intercept on the real part \(\:Z{\prime\:}\) axis of the Nyquist plot for complex impedance \(\:{Z}^{*}\), which is composed of real (\(\:Z{\prime\:}\)) and imaginary (\(\:Z{\prime}{\prime\:}\)) parts. Additionally, the dielectric investigation of the films can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the polarization effect, ion transport properties, and conductivity behavior. In order to accomplish this, the following equations29 can be utilized for determining the dielectric parameters: the one corresponding to stored charges, the dielectric constant \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\), and the component that emphasizes the energy loss caused by the mobility of ions within the electrolyte, the dielectric loss \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\). The \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{*}\) function, which is the sum of the real part (\(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\)) and imaginary part (\(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime}{\prime\:}}\)) of the permittivity as denoted in following equations, is a material characteristic that is influenced by variables such as the type of polymer electrolyte, temperature, and the operating frequency30.

Furthermore, these equations can be utilized to derive the real (\(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\)) and imaginary (\(\:{M}^{{\prime}{\prime\:}}\)) components of the complex electrical modulus, \(\:{M}^{*}\)6,31.

where \(\:\omega\:=2\pi\:f\) represents the angular frequency corresponding to the frequency \(\:f\), the capacitance of a vacuum, denoted as \(\:{C}_{o}\), can be calculated using the equation \(\:{C}_{o}={\varepsilon\:}_{o}A/d\), where \(\:{\varepsilon\:}_{o}\) signifies the free space permittivity.

Results and discussion

FTIR study

FTIR spectroscopy is a key technique for identifying interactions in polymer electrolytes. Shifts in spectral bands indicate coordination between salt cations and polymer functional groups, primarily involving lone pairs on oxygen and nitrogen atoms. The FTIR spectra of pure CS and pure cold-water FSG are presented in Fig. 3(a). In the spectrum of pure CS, a prominent band observed around 3430 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the overlapping amine (N–H) and O–H stretching vibration groups. The symmetric stretching vibrations of carbon atoms bound to hydrogen atoms (C–H) are represented by the absorption bands at about 2927 cm⁻¹ and 2880 cm⁻¹. The bands observed at 1658 cm⁻¹ confirm the presence of residual N-acetyl groups. These bands indicate C = O stretching associated with amide I, while a smaller band at 1598 cm⁻¹ signifies the N–H bending characteristic of amide II32. Additionally, a prominent band at 1320 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C–N stretching associated with amide III. The spectra also display bands around 1424 cm⁻¹ and 1378 cm⁻¹, which confirm the bending of CH2 groups and the symmetrical bending of CH3 groups. The asymmetric stretching of the C–O–C bond corresponds to the absorption band found at 1156 cm⁻¹. Additionally, the bands at 1082 cm⁻¹ and 1030 cm⁻¹ correspond to the stretching vibrations of the carbon-oxygen (C–O) bond. Furthermore, the C–H bending vibration typical of pure CS is indicated by a distinct peak at 898 cm⁻¹. Previous studies32,33 have confirmed that the CS spectra exhibit all characteristic bands identified in this study.

A prominent band at 3395 cm⁻¹ in the pure FSG film attributes to the stretching vibrations of the –OH groups, indicating the presence of hydrogen bonds between molecules, which coincide with the N–H stretching. Additional bands at 2936 cm⁻¹ and 2880 cm⁻¹ are correspond to the symmetric and asymmetric C–H stretching vibrations, commonly observed in polysaccharide structures. In the case of amide I, the characteristic gelatin peaks are most prominently observed at a frequency of 1658 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to the carbonyl (C = O) stretching vibration. Moreover, amide II displays a peak at 1542 cm⁻¹, indicating the nitrogen–hydrogen (N–H) bending vibration. Additionally, a symmetric stretching bond seen at 1451 cm⁻¹ indicates the existence of carboxylic acid (–COOH) groups. The presence of a prominent absorption band at 1241 cm⁻¹ indicates the stretching of the C–N bond within the amide group. The band observed at 1167 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the asymmetric stretching of the C–O–C bridge in gelatin. Additionally, the signals at 1080 cm⁻¹ and 1030 cm⁻¹ correspond to the C–O stretching vibrations of gelatin. In the course of these comprehensive investigations34,35, all characteristic peaks corresponding to gelatin were meticulously identified and analyzed.

The FTIR spectra of the biopolymer blended film composed of CS and FSG are shown in Fig. 3(b). Notable changes in the O–H absorption band were observed as the concentration of FSG raised within the blend sample. In the composite film, a noticeable reduction in both the broadening and intensity of the biopolymer blend was observed. The peak associated with the overlapping O–H and N–H stretching vibrations in the pure polymers shifted to a lower wavenumber at 3307 cm⁻¹, indicating molecular interaction between CS and FSG components. In the blend film, the C–H stretching band was detected at 2949 cm⁻¹, showing a slight shift compared to the corresponding peaks in pure components. Meanwhile, the other C–H band at 2880 cm⁻¹ remained across all samples. These observations suggest molecular interactions between CS and FSG, likely facilitated by hydrogen bonding between O–H and N–H groups. Additionally, electrostatic interactions between O–H groups of FSG and the positive amine groups (NH3+) of CS may occur under acidic conditions, contributing to the structural reorganization within the blend matrix. Moreover, the Amide II band in the composite film appeared at 1539 cm⁻¹, shifted from its positions in the pure components, indicating molecular interactions within the blend. Increasing gelatin content enhanced the intensities of both Amide I and II bands, indicating potential cross-linking and intermolecular interactions involving –OH and –NH2 groups within the polymer matrix. These changes illustrate the formation of a biopolymer blend film composed of CS and FSG, where the positively charged –NH3+ ions from the CS amino group interact with the negatively charged − COO − ions in the carbonyl group of gelatins36.

To demonstrate the complexation that occurs between the CS and FSG host mix polymer with the NH4SCN dopant salt, the FTIR spectra of the produced SPE films are presented in Fig. 4. The interaction between the functional groups of polymers and the salt ions typically alters the bending/stretching vibration modes of specific bonds. The increasing NH4SCN salt concentration induced notable changes in the OH vibrational band of the host, including reduced intensity, band broadening and slight shifts in position. These alterations indicate sat-polymer interactions, likely arising from the complexation of H+ ions from the salt cation with the O–H groups of the host matrix. Additionally, as the salt content increases, the C–H stretching band is significantly reduced because the cations interact with the lone pair electrons of nitrogen in the mixing host. All SPE samples clearly display the characteristic aromatic S–C ≡ N stretching band associated with the -SCN⁻ anion from NH4SCN. As the salt content increases from 8 wt% to 48 wt%, the intensity of this peak rises, accompanied by a minor shift from 2063 cm⁻¹ to 2054 cm⁻¹. A similar observation was reported by Abdulwahid et al.37, where the anion SCN⁻ peak in the CS-PS polymer blend showed comparable interaction behavior. The increase in dissociated anions, coupled with the greater availability of cations for conduction, is highlighted by the rise in the SCN⁻ peak as more salt is added. The hydrogen bonding of the tetrahedral cation NH4+ in NH4SCN salts is well understood to occur through the N–H bonds. This bonding arrangement results in two hydrogen atoms being identically bound, one hydrogen atom being rigidly bound, and the fourth hydrogen atom being loosely bound38. The DC conductivity originates from the facile dissociation of the loosely bound H+ ion, promoted by the polar functional groups of CS: FSG host matrix. This ion can transfer to an adjacent coordination site under the influence of an applied electric field driven by a slight difference in electronegativity. Figure 4 illustrates that upon doping, the characteristic bands associated with N–H, O–H, and C–O functional groups in the pure polymer blend displayed shifts and a reduction in intensity. At extremely high salt concentrations, these bands nearly disappeared. This observation indicates that, rather than just affecting the O–H band, a broad spectrum of bands is involved in the host-salt complexation process39. Evidence of complexation is well-documented in the literature, demonstrating that the binding of cations to the host polymer functional groups leads to an increase in molecular weight. This increase subsequently results in a decrease in vibrational intensity and a shift in peak locations40. Furthermore, the SPE spectra reveal that specific salt-related bands exhibit increased intensity, mainly at 48 wt% concentration, suggesting the possible onset of ion-association at such a highly concentrated level. Achieving high ionic conductivity in SPE requires effective complexation between NH4SCN and the CS: FSG blend. This is supported by shifts in peak locations and intensities relative to the pure blend, indicating electrostatically driven interactions between the salt and the polar functional groups of the polymer matrix. As a result, the amorphous region of the SPE films may expand due to the disruption of some intra- and inter-chain bonds. Based on the preceding analysis, Figure S3 demonstrates the representation of the potential interactions between the CS: FSG biopolymer blend and the incorporated NH4SCN salt.

FTIR Deconvolution analysis

Ion dissociation can be effectively evaluated using FTIR spectroscopy. Through spectral deconvolution in the free-ions region, key transport parameters such as charge carrier number density (\(\:n\)), mobility (\(\:\mu\:\)), and diffusion coefficient (\(\:D\)) can be quantitatively determined. The ionic conductivity of CS: FSG: NH4SCN SPE is linked to these transport parameters. FTIR-based deconvolution techniques may offer more direct or reliable estimates of ion transport parameters because they provide molecular-level insight into ion–polymer interactions. This approach allows for the differentiation between free ions and ion pairs or aggregates based on specific vibrational modes, which is not always directly accessible through macroscopic techniques like impedance spectroscopy or empirical models such as those proposed by Trukhan, Rice and Roth, or Schutt and Gerdes41. The thiocyanate anion (SCN⁻) is a linear molecular ion that has two potential reactive sites. In addition to S-bonding (C–S stretching) and N-bonding (C–N stretching), this ion can form bridge complexes involving both nitrogen and sulfur atoms (S–C–N bending). Consequently, this results in the creation of free ions, particularly H+, which enhances ionic conductivity. For N-bonding to occur, the ionization state of the C–N bond must be highly responsive to stretching, and the absorption intensity should be significant42. Given that the spectral mode of the anion is dominant and distinct from other vibrational modes, it is standard practice to investigate its C ≡ N stretching vibrational mode when examining ion-ion interactions. This band has been analyzed for anions across various configurations, including spectroscopically free ions, contact ion pairs, and ion aggregates43. In their research, Aziz et al.44 state that the C ≡ N stretching mode is highly sensitive to its ionization states and exhibits a strong absorption intensity. Therefore, when studying ion dissociation in SPE using FTIR spectroscopy, the band corresponding to SCN is essential. As shown in Fig. 4, the salted system comprising CS: FSG infused with NH4SCN displays a pronounced peak of SCN. The peak’s intensity increases with concentration of NH4SCN salt in the electrolyte composition. The pronounced intensity of the SCN⁻ stretching mode in the FTIR spectra makes it a reliable probe for investigating ion association phenomena within the SPE system43.

The deconvolution of FTIR spectra for the SCN⁻ stretching modes within the CS: FSG: NH4SCN SPE system, observed in the 2110–1900 cm⁻¹ range, is illustrated in Fig. 5, for different salt concentrations. The solid and dotted lines depict the curve-fitting data, while the black solid line represent the experimental spectra. Prior research indicates that this prominent peak consists of three narrower peaks within the same range. The band at 2074 cm⁻¹ is associated with ion aggregate formation, the peak centered at 2058 cm⁻¹ corresponds to contact (NH4+ & SCN⁻) ions, and the band at 2040 cm⁻¹ relates to free SCN⁻ anions43,45. In the PVA-MC-NH4SCN electrolyte system, overlapping spectra between 2030 and 2090 cm⁻¹ suggest the dynamics of ion association and dissociation, as noted by Shamsuri et al.46. According to Ramya et al.47, the peaks found at 2072 cm⁻¹ indicate the development of ion aggregates, the peak observed at 2061 cm⁻¹ relates to contact ions, whereas the peak observed at 2047 cm⁻¹ is associated with free anions. Woo et al.42 identified a broad peak at 2074, 2062, and 2038 cm⁻¹. To clarify these results, curve fitting was utilized to deconvolute and isolate the bands into distinct component peaks. The percentage of ionic species in the CS: FSG: NH4SCN system was quantifies by calculating the area beneath each corresponding band, as expresses by41.

where \(\:{A}_{f}\), \(\:{A}_{c}\), and \(\:{A}_{a}\) represent the areas beneath the peaks corresponding to free ions, contact ions, and ion aggregates, respectively.

The spectral peak observed in the range of 2033–2036 cm⁻¹ is indicative of the presence of free ions within the system. The peaks ranging from 2070 to 2074 cm⁻¹ signify the occurrence of ion aggregation, which suggests the formation of ionic clusters. The contact ion peaks show an important change as the salt content increases. For 8, 16, 24, and 32 wt% salt, the peaks measure 2051 cm⁻¹. However, when the salt concentration reaches 40 and 48 wt%, these peaks shift down to 1990 cm⁻¹, indicating a change in the ionic environment and interaction dynamics. The percentage of ionic species can be determined by calculating the integral area fraction under the curve, as visually represented in Fig. 5. At a salt concentration of 8 wt%, most of the ionic species in the SPE are contact ions, which make up about 70.25% of all ionic species. In this environment, free ions represent a minor fraction at 14.56%, while ion aggregates account for 15.19%. As the salt concentration is raised to 16 wt%, a notable shift occurs: the proportion of contact ions declines to 62.01%. Concurrently, free ions experience an increase to 18.46%, and ion aggregates also rise to 16.53%, indicating a dynamic change in the ionic interactions present in the solution. When the salt content is further elevated to 24 wt%, the trend continues; the percentage of contact ions falls to 56.69%. In contrast, free ions gain more presence, rising to 23.03%, and ion aggregates further increase to 20.28%. This change indicates that the network of contact ions is becoming less stable, allowing more ions to move freely in the system. At 32 wt% salt concentration, the environment becomes even more ionic active, with contact ions decreasing further to 41.54%. The percentage of free ions has increased to 33.98%, while ion aggregates have risen to 24.48%. Upon reaching a salt concentration of 40 wt%, the proportion of contact ions continues its downward trend, ultimately being recorded at 29.04%. During this stage, free ions peak impressively at 37.62%, while ion aggregates rise to 33.34%.

As the proportion of free ions reaches its peak, the concentration of contact ion pairs diminishes to its lowest level. This decrease in contact ion concentration is attributed to the rising concentrations of both free ions and ion aggregates within the electrolytes. When salt concentration increases, the intensity of the peak for free ions also increases. There is a strong correlation between this increase and the trend in ionic conductivity. Conversely, at a salt concentration of 48 wt%, the distribution of ionic species exhibits a slight change. The percentage of contact ions experiences a slight uptick to 31.07%, meanwhile, free ions diminish somewhat to 31.21%, but ion aggregates significantly increase to 37.72%. The presence of both ion aggregates and contact ions limits the availability of free mobile carriers, resulting in reduced conductivity. According to findings reported by Noor and Isa48 in the PCL-NH4SCN system, the observed increase in conductivity was attributed to a rise in the number of ion dissociations, correlating with the number of free ions produced from the ammonium salt.

The following equations were used to determine the ion transport parameters, including \(\:n\), \(\:\mu\:\) and \(\:D\)41,49:

The charge of an electron, denoted as \(\:e\). Avogadro’s number, represented by \(\:{N}_{A}\). The value of Boltzmann’s constant denoted by \(\:{k}_{B}\). The absolute temperature is indicated by the letter \(\:T\), the number of moles of salt used in the process is represented by \(\:M\), and the total volume of the SPE system is denoted as \(\:{V}_{Total}\).

Figure 6(a) illustrates the percentage distribution of free ions, contact ion pairs, and ion aggregates, while Fig. 6(b) present the correlation between NH4SCN concentration and the ion transport parameters, specifically \(\:D\), \(\:\mu\:\) and \(\:n\). Notably, when the concentration of salt rises, the \(\:n\) tends to increase gradually. Meanwhile, it is shown that the \(\:D\) and \(\:\mu\:\) follow the trend in ionic conductivity. It is important to note that the value of the free ion, which gradually improved by adding more salt to the system, indicates that the ionic conductivity of the current system is enhanced by raising the \(\:n\) value. The addition of salt increases chain flexibility, which in turn causes an increase in the \(\:D\) and \(\:\mu\:\). This occurs as a result of the incorporation of more salts into the free ions, which ultimately results in an increase in the total number of charge carriers present in the system. As the concentration of NH4SCN increases to 48 wt% in this study, the value of \(\:n\) also rises correspondingly. This increase in NH4SCN incorporated into the CS: FSG-based electrolytes leads to a higher number of charge carriers being produced. However, the behavior of \(\:D\) and \(\:\mu\:\) exhibits a distinct trend. Specifically, as NH4SCN concentration rises from 8 to 40 wt%, the \(\:D\) value increases significantly from \(\:3.18\times\:{10}^{-12}\:{cm}^{2}{s}^{-1}\) to \(\:9.24\times\:{10}^{-11}\:{cm}^{2}{s}^{-1}\). Similarly, the \(\:\mu\:\) value experiences an increase from \(\:1.22\times\:{10}^{-10}\:{cm}^{2}{V}^{-1}{s}^{-1}\) at 8 wt% to \(\:3.54\times\:{10}^{-9}\:{cm}^{2}{V}^{-1}{s}^{-1}\) at 40 wt% and the value of \(\:n\) ranges from \(\:1.06\times\:{10}^{21}\:{cm}^{-3}\) to \(\:2.10\times\:{10}^{22}\:{cm}^{-3}\), as presented in Table 3.The enhancement in these two transport characteristics upon doping the CS: FSG blend with NH4SCN suggests an improvement in the chain flexibility of the mixture. As previously mentioned, an increase in salt concentration elevates the value of \(\:n\), which subsequently affects the values of \(\:\mu\:\) and \(\:D\). An optimal salt content allows the polymer blend to create a conducive environment for ion migration and balanced interactions. This finding aligns with the study by Ramli and Isa50, which demonstrated that the electrolyte exhibiting the highest conductivity also had the greatest values of \(\:\mu\:\) and \(\:D\). However, at 48 wt% salt concentration, a reduction in \(\:\mu\:\) is observed, attributed to ion overcrowding and recombination of free ions, which reduces the mobility and migration capacity of ions within the polymer matrix. Consequently, both \(\:\mu\:\) and \(\:D\) decrease in accordance with the drop in ion density. The crystallization pattern observed in the XRD analysis, discussed in the XRD section, suggests that the dipole interactions involving H+ in the CS: FSG: NH4SCN system are altered at this concentration.

XRD analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a nondestructive and highly powerful technique for examining the atomic configurations of SPEs. It provides insights into crystallinity and its impact on ionic conductivity41. The amorphous phase in SPEs is particularly important for ion transport, as enhanced polymer chain mobility in these regions, due to lowered energy barriers and increased interchain spacing, facilitates dipole reorientation and ion migration11. The XRD patterns of the pure polymers (CS & FSG) as well as the polymer blended films are provided in the supplementary materials, Figure S4. In accordance with the earlier research from the literature49,51, the presence of several crystalline peaks, accompanied by two broad amorphous beaks positioned at approximately 2θ = 20° and 40° confirms the semicrystalline nature of CS matrix. The study of pure gelatin using XRD shows that it has a primarily amorphous structure, which is determined by the presence of a large diffuse band observed at around 2θ = 20° degrees. This XRD pattern is consistent with previous reports on gelatin films and is commonly observed in related structural analyses52,53,54,55. Figure S4 shows that there is a noticeable decrease in crystalline peak intensities and the elimination of some peaks when these two polymers are blended in a ratio of 20 wt% CS: 80 wt% FSG. As a result of the breaking of interchain molecular hydrogen bonds, the chain spacing increases, the disordering becomes more elongated, and crystallinity is reduced. In the case of the CSFSG2 sample, an additional decrease in the crystalline peaks can be noted. Notably, the CSFSG3 sample exhibits a fully amorphous structure, evidenced by the absence of crystalline regions and the presence of broad diffuse humps. On the other hand, the re-growth of crystalline areas is evident in the CSFSG4 sample, which shows the reappearance of several crystalline peaks from the previous figure with greater intensities. The XRD results led to the selection of CSFSG3 as the host for the synthesis of electrolytes. This host exhibits the highest amorphous content, ensuring full polymer miscibility and enhanced ionic transport. The degree of crystallinity (\(\:{\chi\:}_{c}\)) was subsequently evaluated to examine structural changes and resolve overlapping peaks between amorphous and crystalline phases using XRD deconvolution, as defined by the following equation:

In the deconvoluted XRD analysis of the SPE films, the amorphous peaks are represented by broad and wide peaks, whereas the crystalline peaks are identified by fine, sharp, and distinct peaks. The XRD diffractograms and deconvoluted XRD analysis for CS: FSG doped with NH4SCN salt SPE films are presented in the Fig. 7 and Figure S5, respectively.

Notably, the intensity of the hump associated with the CS: FSG blend gradually diminishes with increasing salt content. Concurrently, the sharp crystalline peaks characteristic of pure NH4SCN salt decrease in intensity upon the addition of 8, 16, 24, and 32 wt% of NH4SCN. At higher salt concentration of 40 wt% and 48 wt%, several new peaks of weak intensity emerge. These are attributed to the formation of ion multiplets, indicating enhanced ion association at elevated salt concentrations56. Importantly, the XRD pattern of the CGNHSCN40 film, containing 40 wt% salts, exhibits the most amorphous structure, characterized by the broadest and weakest hump, alongside a single crystalline peak. In comparison to the other samples, CGNHSCN40 displayed a lower degree of crystallinity, with a spectral value of 4.09%. The hydrogen bonding significantly decreased due to the electrostatic interactions between the polar functional groups of the CS: FSG host matrix and the NH4SCN cation. This led to an enhancement of the amorphous phase and facilitated effective complexation. However, when the salt content reached 48 wt%, there was a notable increase in hollow intensity, accompanied by additional crystalline peaks. This phenomenon is attributed to the association of free ions, which occurs as the host’s accommodation becomes restricted at such a high salt concentration57. The findings from these analyses indicate that the amorphous CGNHSCN40 film is likely the most efficient at dissociating the salt and promoting the migration of free ions within the SPE through conduction. Further validation of this assertion will be provided through EIS studies and the calculation of ion transport parameters.

Impedance study

EIS is a reliable and effective method for assessing the ionic conductivity of SPEs. Impedance plots serve as a crucial tool for ascribing the electrical characteristics of polymer electrolytes, providing valuable insights into resistance, capacitance, and ionic mobility, making them particularly relevant for applications in energy storage devices31. Nyquist plots of polymer-based electrolytes typically display semicircles, spikes, or a combination of both, each corresponding to specific electrochemical features. A semicircle reflects bulk resistance and charge transfer processes, while a spike indicates interfacial capacitance associated with polarization and ionic diffusion. Figure 8 presents the Nyquist plots (Z′ vs. Z″) for the CS: FSG: NH4SCN SPE system at various salt concentrations. The findings of this study consistent with prior research, where the plots exhibited semi-circular arcs for sample CGNHSCN8 and semi-circular with a spike for other higher salt concentrations. To evaluate the suitability of the electrolyte for energy storage applications, which require optimal ionic transport and interfacial properties, this type of analysis is crucial.

Two distinct regions are evident: a high-frequency semicircle arising from the parallel combination of a resistor and capacitor, and a low-frequency inclined spike caused by blocking electrodes in the biopolymer electrolyte loaded with NH4SCN. The inclination reflects double layer effects at the blocking electrodes. Ramya et al.58 have noted that this inclination may also arise from the roughness of the electrode-electrolyte interface. It is important to note that increasing the concentration of the NH4SCN salt leads to noticeable reduction in the diameter of the high-frequency semicircle, indicating a decrease in bulk resistance and enhanced ionic conductivity within the electrolyte system48,59. At the microscopic level, the ionic conductivity of the electrolyte is influenced by three primary factors: the concentration of charge carriers, \(\:n\), the charge of the mobile carriers, \(\:q\), and the mobility of these carriers, \(\:\mu\:\).

Equation indicates that enhancing ionic conductivity \(\:\sigma\:\) requires increasing \(\:n\) and \(\:\mu\:\). When more salt is added to the polymeric matrix, the \(\:n\) increases. However, this rise in salt content can hinder the \(\:\mu\:\) of the polymer segments, as it may impair the polymer’s ability to solvate the salt due to interactions between metal cations and ether oxygen atoms. Consequently, increased salt content in SPEs may lead to reduced ionic conductivity, enhanced ion association, and potential crystalline complex formation. Understanding this relationship offers insights into the specific interactions between the salt and the polymer matrix. By pinpointing the location of the semi-circle intersection on the horizontal axis (\(\:{\:Z}^{{\prime\:}}\)), the bulk resistance (\(\:{R}_{b}\)) was calculated from the impedance plot. The ionic DC conductivity (\(\:{\sigma\:}_{dc}\)) was readily determined by applying Eq. (1) alongside a comprehensive understanding of the sample’s geometry. Table 4 displays the \(\:{\sigma\:}_{dc}\) values for each SPE film at ambient temperature. As the concentration of the NH4SCN salt in the biopolymer blend electrolyte gradually increased, a significant decline in the \(\:{R}_{b}\) of the SPE film was noted. This decrease in resistance is further demonstrated by the corresponding reduction in the diameter of the semicircle. The conductivity of the samples improved, as indicated by the continued shrinkage of the arc and the emergence of a tail with increasing NH4SCN content up to 40 wt%. At this concentration the conductivity reached its peak at \(\:1.19\times\:{10}^{-5}\:S\:{cm}^{-1}\). The increase in salt content results in a greater density of available mobile ions, thereby enhancing \(\:{\sigma\:}_{dc}\).

Proton transfer typically occurs through two primary mechanisms: The vehicular mechanism, where protons are transported by carrier molecules, and structural diffusion, involving proton hopping between hydrogen-bonds sites60. This latter mechanism enables more efficient proton transfer since it does not require the mobility of entire molecules. Additionally, the process of sequential proton transfer allows for the establishment of a collective mechanism that spans multiple molecules61. This concept was first proposed by Grotthuss to elucidate observations made during water hydrolysis62. A substantial body of previous research indicates that the Grotthuss mechanism is viewed as the most effective method for conductivity, as it facilitates a collective chain-like transfer of protons, enabling the net charge to be transmitted more swiftly than the protons themselves60,61,63.

The Grotthuss mechanism is responsible for transporting protons in polymer electrolytes. As a result of the transfer of H+ ions from one location to another, a vacancy is created, which will be filled by another proton ion from a nearby location. As illustrated in Figure S6, the Grotthuss mechanism facilitates proton transport through proton exchange between complexed polymer-salt sites. In low relative humidity, the vehicle’s mechanism causes the mobility to be less, whereas in higher relative humidity, the mobility is greater. On the other hand, the vehicle mechanism gradually takes over as the temperature rises and hydrogen bonds start to lengthen and break64.

The introduction of salt into the host medium led to changes in its structural characteristics, transforming crystalline sections into interconnecting amorphous regions, as indicated by the XRD data. In these amorphous regions, mobile ions can easily move from one site to another due to the greater degrees of rotational freedom and rapid segmental motion of the polymer chains and site groups. The findings from the FTIR spectroscopy indicated that the increased area of the amorphous phase allowed more free ions to move, resulting in enhanced mobility. As a result, at 40 wt% NH4SCN salt, the ionic conductivity increased due to both a higher concentration of charge carriers and improved ionic mobility. When the salt content increases to 48 wt%, there is a notable rise in \(\:{R}_{b}\), accompanied by a decrease in \(\:{\sigma\:}_{dc}\). At this elevated level of salt concentration, free ions tend to form ion pairs and clusters, leading to an increase in the re-association of ions relative to the dissociation rate65. This phenomenon is further supported by FTIR results, which indicates that the mobility of ions in the system is reduced due to the decline in the total number of free ions and an increase in the crystallinity of the host matrix, as discussed in the XRD section. Previous studies have indicated a decline in ionic conductivity at higher salt concentrations. For instance, in a PVA-CS blended electrolyte solution, Kadir et al.66 demonstrated that ionic conductivity decreased as the concentration of NH4NO3 was increased to 50 wt%. Similarly, Abdulwahid et al.37 found that exceeding 50 wt% of NH4SCN in a CS-PS matrix resulted in reduced conductivity. Furthermore, Hema et al.38 observed a comparable trend in a PVA host matrix doped with NH4Cl, NH4Br, and NH4I, noting that conductivity diminished as salt concentration increased.

Electric Equivalent Circuits (EEC) models and impedance spectrum analysis provide valuable electrical system data that deepen our understanding of sample behavior. The EEC model integrates resistors and constant phase element (CPE) arranged in both parallel and series configurations to simulate the electrical response of SPE systems. The semi-circle in the impedance spectra at high frequencies represents a parallel connection between a CPE1 element and resistance \(\:{R}_{b}\), while CPE2 in series is associated with the interval spike67. Specifically, CPE1 indicates the properties of the bulk SPE film, while CPE2 represents the electric double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface. The impedance of a CPE is described by a specific equation37.

In this context, \(\:C\) denotes the capacitance of the CPE, \(\:\omega\:\) represents the angular frequency, and \(\:p\) is a dimensionless fitting parameter that varies between 0 and 1. When the \(\:p\)-value reaches 1, the CPE functions as an ideal capacitor. In cases where the impedance plot reveals only a high-frequency semicircle, specific equations can be derived for the real (\(\:{Z}^{{\prime\:}}\)) and imaginary (\(\:{Z}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\)) components, as illustrated in following equations:

\(\:\text{W}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}\text{e}\:{\alpha\:}_{A}=C{\omega\:}^{p}\text{cos}\left(\frac{\pi\:p}{2}\right)\:;\:{\beta\:}_{A}=C{\omega\:}^{p}\text{sin}\left(\frac{\pi\:p}{2}\right);\:{\gamma\:}_{A}={C}^{2}{\omega\:}^{2p}\).

The \(\:{p}_{1}\) value for the electrolytes CGNHSCN16, CGNHSCN24, CGNHSCN32, CGNHSCN40, and CGNHSCN48 defines the shape geometry of the arc as it deviates from a perfect semicircle. Meanwhile, \(\:{p}_{2}\) tracks the variations of the spike in the low frequency range, also stated to as the deviation from the horizontal baseline68.

where \(\:{\alpha\:}_{B}={C}_{1}{\omega\:}^{{p}_{1}}{cos}\left(\frac{\pi\:{p}_{1}}{2}\right)\); \(\:{\beta\:}_{B}={C}_{1}{\omega\:}^{{p}_{1}}{sin}\left(\frac{\pi\:{p}_{1}}{2}\right)\); \(\:{\gamma\:}_{B}={C}_{1}^{2}{\omega\:}^{2{p}_{1}}\); \(\:{\chi\:}_{a}=\frac{{cos}\left(\frac{\pi\:{p}_{2}}{2}\right)}{{C}_{2}{\omega\:}^{{p}_{2}}}\:\); \(\:{\chi\:}_{b}=\frac{{sin}\left(\frac{\pi\:{p}_{2}}{2}\right)}{{C}_{2}{\omega\:}^{{p}_{2}}}\)

The experimental results closely matched the fitted data lines, and the fitting parameters were summarized in Table 4. The addition of NH4SCN led to an increase in the values of CPE2, indicating a higher ion concentration within the SPE. This elevated ionic concentration enhanced the typical resistance of the electrodes, subsequently resulting in increased capacitance in the low frequency range. The performance of the SPE improved as more ions became mobilized, allowing for greater ionic conduction across the material. Furthermore, our simulated capacitance results aligned well with those reported in existing investigations31.

It is important to note that the transport parameters obtained from EIS data are quite similar to those derived from FTIR spectroscopy analysis. Key parameters such as the \(\:D\), \(\:\mu\:\) and \(\:n\) are derived from the impedance plot, which typically features a spike and semicircle31,41. These elements form the mathematical basis for analyzing ion transport behavior and interfacial processes in SPE systems. The following equation is used to calculate \(\:D\):

where \(\:{K}_{2}\) denotes the value corresponding to the reciprocal of CPE2 as outlined in Table 4, and \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\) signifies the reciprocal of the angular frequency at which the minimum in \(\:{Z}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) occurs, specifically at the location where the spike was established. The following equations can be employed to calculate the value of \(\:\mu\:\), \(\:{\sigma\:}_{dc}\), and \(\:n\):

Table 5 illustrates the impact of increasing NH4SCN concentration on the transport parameter of SPE films. Fundamentally, CS: FSG-based biopolymer electrolytes generate more charge carriers as the salt content increases. Notably, increasing NH4SCN concentration from 8 to 48 wt% significantly enhances the value of \(\:n\). The increase in chain flexibility resulting from the doping process is evidenced by the improved transport properties. Equation (21) indicates that \(\:D\) is influenced by three parameters: \(\:{K}_{2}\), \(\:{\varepsilon\:}_{r}\), and \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\). This interdependence introduces complexity, making it challenging to obtain values of \(\:D\) and \(\:\mu\:\) that align with the trend observed in \(\:n\). The decrease in \(\:D\) and \(\:\mu\:\) can be attributed to the high ion concentration, which leads to increased interactions among free ions at various sites. As depicted in Figure S7, both the mobility and diffusivity of the ions are adversely affected due to the reduced surface area. Although FTIR and EIS yield transport values differing by about an order of magnitude, this arises from differences in their probing scale molecular (FTIR) versus bulk (EIS). Despite this, both methods show consistent trends, reinforcing the reliability of the ion transport analysis.

Dielectric constant and dielectric loss

The frequency-dependent permittivity response is a powerful tool for studying dipolar relaxation and ion mobility in polymer blend electrolytes. It provides insights into ionic/molecular interactions, structural features, and the distinct roles of bulk and interfacial regions in SPE performance69,70. The log-scale variation of the real part of the dielectric constant (\(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\)) as a function of frequency is shown in Fig. 9(a), while the corresponding variation in the imaginary part (\(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\)) is presented in Fig. 9(b), both measured at ambient temperature. The measurements commenced with high values in the low frequency region, followed by a rapid decrease in the mid-frequency range, ultimately stabilizing at high frequencies. In the low frequency region, the applied alternating field facilitates the movement of ions toward the interface, resulting in electrode polarization20. Enhanced values of \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\:\)and \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) arise due to this electrode polarization, as oriented dipoles require sufficient time to align with the direction of the applied field. The elevated dielectric values at low frequencies are primarily attributed to the presence of mobile NH4SCN ions and the polar functional groups of the CS: FSG polymer blend. In contrast, at higher frequencies, the rapid switching of the applied AC inhibits the ability of charge carriers to realign with the changing polarity, resulting in a decline and eventual stabilization of the dielectric response. In this scenario, the orientation-induced polarization becomes limited, and long-range ion migration ceases, resulting in stabilized dielectric properties31. Within the bulk of the SPE films, the polarized molecules reach a state where both the \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) values remain constant. The dielectric loss is higher than that of dielectric constant, a common observation in various SPEs systems reported by previous studies. The high value of \(\:\varepsilon\:{\prime\:}{\prime\:}\) in comparison to \(\:\varepsilon\:{\prime\:}\) ascribed to the contribution of DC conductivity to the \(\:\varepsilon\:{\prime\:}{\prime\:}\) value based on Maxwell equation. Fabrication of SPEs with high value of \(\:\varepsilon\:{\prime\:}\) compared to \(\:\varepsilon\:{\prime\:}{\prime\:}\) value is a challenge in the field of SPEs and will open new era for electrochemical devices with high performances.

The dependence of the dielectric constant peaks intensity on NH4SCN concentration is illustrated in Fig. 9(c). As the concentration of NH4SCN increased, the dielectric constant \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) continued to rise, reaching its peak in the sample with 40 wt% NH4SCN. The improved dissociation of the salt leads to an increase in free charge carriers within the polymer, corroborating the effective ion transport parameters indicated by the FTIR test results. The effective permittivity of the system correlates directly with the charge carrier density (\(\:n\)), described by the formula \(\:n={n}_{o}\:{e}^{(-U/{\varepsilon\:}_{r}{k}_{B}T)}\), where \(\:U\) represents the dissociation energy20. As cations and anions experience a weaker electrostatic force within the polymer matrix, more charge carriers become available. In contrast, the FTIR and XRD results indicated a decrease in both \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) values in CGNHSCN48, attributed to the increased salt concentrations, which reduced the number of mobile ions and enhanced crystallinity. Shukur et al.71 reported similar findings in their study on CS-PEO polymer blend electrolytes, noting a comparable outcome when the addition of NH4NO3 exceeded 50 wt%. Our findings suggest that the movement of charge carriers induces a higher degree of polarization through free ion displacement compared to the contribution from dielectric (dipolar) polarization.

Loss tangent \(\:\left({tan}{\delta\:}\right)\)

In SPE systems, the dielectric loss tangent (\(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\)) serves as a critical parameter for quantifying energy dissipation within the dielectric material, specifically, the proportion of energy converted into heat versus that stored during each cycle of dielectric relaxation. In this study, the dielectric performance of the prepared SPE films is assessed through \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) versus \(\:\text{log}\left(f\right)\) plots, providing insights into the relaxation mechanisms governing ion transport, as shown in Fig. 10(a). The graphical representation shows that \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) steadily increases until it reaches a peak at a specific frequency, after which it declines as the frequency surpasses that point. This behavior is a result of the interplay between resistive characteristics dominating the low-frequency region and the peak in rotational molecular motions occurring when the electric field aligns with molecular rotation72. As frequency increases, the impact of the resistive component on \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) diminishes, allowing the reactive part to become more significant. The highest energy transfer observed at specific frequencies corresponds to the peak of the plot, serving as a practical indicator for applications. The presence of relaxing dipoles in each system was confirmed by the variations in peak position and intensity with changes in the concentration of NH4SCN salt. With increasing salt concentration, the \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) peak shifts toward higher frequencies as shown in Fig. 10(b), indicating a reduction in relaxation time due to enhanced ion migration through coordination sites in the polymer backbone. Among all the samples tested, the CGNHSCN40 film exhibited the fastest dipole movements and the shortest relaxation times, as well as the highest peak shift frequencies. Our analysis demonstrated that the CGNHSCN40 sample exhibited the highest ionic conductivity, accompanied by a superior level of amorphous phase. The reduced relaxation period allows polymer chains to move more freely, facilitating the transfer of H⁺ ions between segments73.

Through EIS and XRD, it was established that the 40 wt% NH4SCN polymeric electrolyte film achieved the highest ionic conductivity. The observed improvement arises from increased charge carrier concentration and enhanced mobility due to lower crystallinity. Increasing the salt content to 48 wt% shifted the \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) peak to lower frequencies, indicating longer relaxation times due to increased crystallinity, which hindered chain mobility and ion transport. The frequency dependence of the \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) data can be better understood through Koop’s model and its electrical circuit representation74. This model illustrates that \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) rises with frequency until it reaches a peak, as resistive Faradaic current begins to dominate over capacitive non-Faradaic current at lower frequencies28. At elevated frequencies, the capacitive component gains more influence as the resistive part diminishes, leading to a decrease in \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) values. While the resistive aspect of the electrical circuit remains relatively stable, the capacitance component responds dynamically to changing frequencies75. In this study, relaxation behavior shows agreement with both structural and conductivity findings. This indicates that \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) is a valuable tool for detecting structural changes in the polymer matrix, an aspect that has not been extensively explored before.

AC conductivity \(\:{({\sigma}}_{{A}{C}})\) analysis

To understand the charge carrier dynamics and transport mechanisms, the frequency-dependent electrical conductivity of the current SPE membranes was analyzed across varying NH4SCN salt concentrations. It is crucial for researchers and technological specialists to acquire this knowledge in order to gain insights into the transport of charge within polymer electrolytes. Since specialized ion-conducting electrodes are not needed for analyzing frequency-dependent AC conductivity, it is a frequent approach in polymer electrolyte systems. The \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\) of each SPE film was calculated using the following equation75.

The variation of \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\) as a function of frequency at room temperature is shown in Fig. 11(a) for samples CGNHSCN8, CGNHSCN16, CGNHSCN24, and in Fig. 11(b) for samples CGNHSCN32, CGNHSCN40, CGNHSCN48. These SPE films exhibit electrical conductivity behavior that is in accordance with Jonscher’s power law within the frequency-dependent dispersion region. Such behavior indicates that the charge transport mechanisms in these films are influenced by the interactions of the electric field with the polymer matrix and the mobile charge carriers according to equation76.

where, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{\left(\omega\:\right)}\) denotes the total conductivity coming from both AC and DC currents, with \(\:{\sigma\:}_{DC}\) standing for the frequency-independent conductivity. The frequency exponent \(\:s\) relates to the relaxation time and hopping rate of the site groups, taking values between 0 and 1, while the parameter \(\:{\Lambda\:}\) is influenced by the composition and temperature of the sample.

The \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\) spectra of SPEs typically exhibit three distinct regions: (i) low-frequency dispersion due to interfacial polarization, where charge accumulation at the electrode–electrolyte interface limits mobile ion accessible28; (ii) a mid-frequency plateau corresponding to long-range ion transport, where \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\approx\:{\sigma\:}_{DC}\) due to the short field duration preventing interfacial charging77; and (iii) high-frequency dispersion associated with bulk relaxation, arising from ion hopping driven by Coulombic interactions with polar sites in the polymer matrix75,77.

Increasing salt concentration enhances the flexibility of the host polymer chains by forming complexes with its functional groups. This interaction reduces intra- and inter-molecular tensions, thereby improving segmental chain dynamics and rotational flexibility. These effects are notably observed in the SPE loaded with 40 wt% NH4SCN salt. It is evident that \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\) gradually increases with rising salt content, and the CGNHSCN40 sample exhibiting the highest \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\) value of \(\:1.19\times\:{10}^{-5}\:S\:{cm}^{-1}\), closely aligning with the \(\:{\sigma\:}_{DC}\) value obtained from impedance analysis. Consequently, this enhancement facilitates ion hopping from one unoccupied adjacent site to another, resulting in higher conductivity. However, at 48 wt% salt, a decline in \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AC}\) is observed in the SPE film. In accordance with the XRD and EIS data, this reduction can be attributed to the formation of salt crystals, which restricts chain mobility and decreases the availability of free ions.

The room-temperature ionic conductivity obtained in the present study aligns well with values reported in previous works on various biopolymer electrolyte systems, as shown in Table 6. This comparison underscores the consistency of our findings within the broader context of biopolymer-based SPE research.

Modulus analysis

Electrical modulus analysis provides insight into the dielectric properties of polymer electrolytes. This approach is particularly effective in suppressing electrode polarization and revealing high-frequency relaxation phenomena31. Figure 12(a) shows the real component (\(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\)) of the electrical modulus when adding NH4SCN salt to the CS: FSG-based electrolyte films. The value of \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\) steadily rises at a consistent rate as the frequency increases until it attains its highest value, (\(\:{\text{M}}_{{\infty\:}}=1/{\varepsilon\:}_{{\infty\:}}\)). This phenomenon occurs due to the charge carriers’ movement when applying an electric field69. Conduction mechanisms arising from the passage of ion carriers through short distances may be reflected in the peak value of \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\)84. Interestingly, this observation is contradicted by the finding that \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\) tends to decrease as the salt content increases. The observed reduction in \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\) in the low-frequency region, accompanied by an increase in \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}\), reflects the effect of higher salt content, which enhances the mobility and charge carriers of the polymer85. Figure 12(b) shows the frequency dependence of the imaginary electric modulus (\(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\)) at various salt contents. The prominent peak in the \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) spectra indicates a relaxation process. This peak underscore an important connection between the ions and the segmental motions of polymers, a relationship that is notably absent in the \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) spectra. When carriers experience higher motion velocities over shorter distances, the transition from long-distance ionic mobility to short-distance mobility is indicated by the peak in the \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) spectrum69. This peak will display Debye-like characteristics if the source of conductivity in the spectrum is the mobility of free ions within the polymer, rather than dipolar relaxations and viscoelasticity31. Nevertheless, the sample used in our study does not demonstrate this property, suggesting that its behavior is not Debye-like. The broad and asymmetric shape of the \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) spectra is attributed to the prolonged exponential decay of the electric field, which follows the stretched exponential function:

To characterize Debye-type relaxation behavior, the full width at half maximum (FWHM), denoted as \(\:w\), is commonly employed. For ideal Debye behavior, \(\:w=1.14\), and deviations are quantified using the stretching exponent \(\:\beta\:\), estimated by \(\:\beta\:=1.14/w\). In comparison to the peaks observed in the \(\:\text{tan}\delta\:\) spectra, it is important to highlight that the \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) spectra exhibited a greater prominence of relaxation peaks at higher frequencies. This was anticipated, as the formalism of the electric modulus naturally mitigated certain negative factors impacting dielectric polarization at lower measurement frequencies. Among all the samples analyzed, the CGNHSCN40 sample demonstrated the lowest peak intensity while exhibiting the highest conductivity at room temperature. A shorter relaxation time was associated with an increased conductivity and decreased peak intensity, indicating that charge carriers are likely linked to the polymer matrix instead of being spread out throughout the network. Furthermore, all SPE films exhibited a single \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) relaxation peak, indicating a strong coupling between polymer segmental motion and ion mobility.

Argand plot study

The Argand plot provides insight into the relaxation phenomena occurring in the SPE samples. As shown in Fig. 13, the plot illustrates the relationship between \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) and \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\) for all prepared SPE films at room temperature. Dipolar relaxation, arising from the presence of permanent dipoles along the polymer backbone, can induce molecular or viscoelastic relaxations in polymer-based systems86. The non-Debye behavior observed in this particular form of relaxation is defined by a semicircular arc in the Argand plot, where the diameter of the arc is located below the \(\:M{\prime\:}\) axis. This type of relaxation is characterized by a distribution of relaxation times87. Conversely, there is the potential for conductivity relaxation, a phenomenon that can occur due to the translational diffusion of ions, which is directly linked to the growth of ionic conductivity86. The presence of distribution relaxation, particularly viscoelastic relaxation, is evidenced in the current SPE systems, which display a deformed semi-circular arc, as illustrated in Fig. 13, where the radius lies below the \(\:{M}^{{\prime\:}}\) axis. Consequently, the loss tangent analysis revealed a strong correlation between ion movement and segmental mobility. This is further supported by EIS results, which show a decreasing impedance arc radius with increasing salt concentration. This change signifies a decrease in relaxation time, which effectively enhances the ionic conductivity57. In general, inhomogeneity, the hopping process, space-charge effects, electronic polarization, ion-dipole interactions, and the deviation of polymer electrolytes from a semi-circular profile are the primary factors contributing to the dispersion of relaxation times88. Similar observations have been reported across various SPE systems. For instance, Abdulwahid et al.37 demonstrated that increasing the concentration of NH4SCN salt in a CS: PS host matrix at ambient temperature has the same effect of decreasing arc diameter in the Argand plot and improving ionic conductivity. Through the emergence of an incomplete semicircle arc, they also recorded non-Debye behavior and extensive relaxation times in their systems.

Conclusions

In conclusions, a series of CS: FSG-based solid biopolymer electrolytes with varying NH4SCN contents were effectively prepared and comprehensively characterized. XRD structural analysis confirmed the semi-crystalline nature of the host biopolymer blend. Notably, the incorporation of salt, especially at 40 wt%, led to an increase in amorphous content, which associated with improved ionic transport properties. FTIR analysis confirmed effective biopolymer-salt complexation and highlighted the crucial role of free ion formation in facilitating ionic conduction. The ion transport parameters, namely, charge carrier density, mobility, and diffusion coefficient, were assessed using both FTIR spectral deconvolution and EIS measurements. The close alignment of outcomes from both techniques validates the reliability of FTIR analysis in probing ion dissociation and transport behavior within the polymer matrix. Notably, the system doped with 40 wt% NH4SCN exhibited optimal transport properties. However, exceeding this concentration led to decline in transport performance due to ion aggregation and recombination effects. These findings were reinforced through dielectric and electric modulus studies, highlighting non-Debye relaxation behavior, dipolar contributions, and frequency-dependent dielectric loss. Additionally, the emergence of incomplete semicircular arcs and the reduction in arc diameter in the Argand plots of CS: FSG: NH4SCN SPE indicated extended relaxation processes and inhanced ionic conductivity at the optimal salt concentration. Altogether, this study underscores the influence of salt concentration in modulating the electrochemical response of the biopolymer blend matrix, thereby providing valuable insights for engineering bio-derived SPEs for high-performance energy storage applications.

Data availability

All data is provided in full in the results section of this paper.

References

Mazhandu, Z. S., Muzenda, E., Mamvura, T. A., Belaid, M. & Nhubu, T. Integrated and consolidated review of plastic waste management and bio-based biodegradable plastics: challenges and opportunities. Sustainability 12, 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208360 (2020).

Borrelle, S. B. et al. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 369, 1515–1518. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba3656 (2020).

Alipal, J. et al. A review of gelatin: properties, sources, process, applications, and commercialisation. Mater. Today Proc. 42, 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.922 (2021).

Chalkias, D. A. et al. High-efficiency quasi-solid state dye-sensitized solar cells using a polymer blend electrolyte with polymer-in-salt conduction characteristics. Sol. Energy. 222, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2021.04.051 (2021).

Chong, M. Y. et al. Enhancing the performance of green solid-state electric double-layer capacitor incorporated with fumed silica nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 117, 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.02.030 (2018).

Prasanth, S. R., Prasannavenkadesan, V., Katiyar, V. & Achalkumar, A. S. Polymer electrolytes: evolution, challenges, and future directions for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Appl. Polym. 3, 499–531. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4LP00325J (2025).

Bharti, V., Singh, P. K. & Sharma, J. P. Development of polymer electrolyte membranes based on biodegradable polymer. Mater. Today Proc. 34, 856–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.06.463 (2021).

Orlins, S. & Guan, D. China’s toxic informal e-waste recycling: local approaches to a global environmental problem. J. Clean. Prod. 114, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.090 (2016).

Vijaya, N., Selvasekarapandian, S., Sornalatha, M., Sujithra, K. S. & Monisha, S. Proton-conducting biopolymer electrolytes based on pectin doped with NH4X (X = Cl, Br). Ionics (Kiel). 23, 2799–2808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-016-1852-5 (2017).

Monisha, S., Mathavan, T., Selvasekarapandian, S., Benial, A. M. F. & latha, M. P. Preparation and characterization of cellulose acetate and lithium nitrate for advanced electrochemical devices. Ionics (Kiel). 23, 2697–2706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-016-1886-8 (2017).

Shukur, M. F. & Kadir, M. F. Z. Electrical and transport properties of NH4Br-doped cornstarch-based solid biopolymer electrolyte. Ionics (Kiel). 21, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-014-1157-5 (2015).

Samsudin, A. S. & Isa, M. I. N. Structural and ionic transport study on CMC doped NH4Br: A new types of biopolymer electrolytes. J. Appl. Sci. 12, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2012.174.179 (2012).

Aziz, S. B. et al. Plasticised chitosan: dextran polymer blend electrolyte for energy harvesting application: tuning the ion transport and EDLC charge storage capacity through TiO2 dispersion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 273, 133203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133203 (2024).

Selvalakshmi, S., Vijaya, N., Selvasekarapandian, S. & Premalatha, M. Biopolymer agar-agar doped with NH4SCN as solid polymer electrolyte for electrochemical cell application. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134, 44702. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.44702 (2017).

Kadir, M. F. Z. Non-Faradaic-based supercapacitor fabricated with fish skin gelatin biopolymer electrolyte. Ionics (Kiel). 27, 2219–2229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-021-03992-4 (2021).

Ravi Kumar, M. N. V. A review of Chitin and Chitosan applications. React. Funct. Polym. 46, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1381-5148(00)00038-9 (2000).

Da Silva, E. et al. FH. Development and optimization of biodegradable fish gelatin composite film added with buriti oil. CyTA - J Food ;16:340–9. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/19476337.2017.1406005

Piana, G., Bella, F., Geobaldo, F., Meligrana, G. & Gerbaldi, C. PEO/LAGP hybrid solid polymer electrolytes for ambient temperature lithium batteries by solvent-free, one pot Preparation. J. Energy Storage. 26, 100947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.100947 (2019).

Mallaiah, Y. et al. Impact of polymer blending on ionic conduction mechanism and dielectric properties of sodium based PEO-PVdF solid polymer electrolyte systems. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 155, 110096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110096 (2021).

Arya, A., Sadiq, M. & Sharma, A. L. Salt concentration and temperature dependent dielectric properties of blend solid polymer electrolyte complexed with NaPF6. Mater. Today Proc. 12, 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.03.098 (2019).

Sethi, S. & Medha, Kaith, B. S. A review on chitosan-gelatin nanocomposites: synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 179, 105362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2022.105362 (2022).