Abstract

This study explores the coherent control of the photonic spin hall shift through a configuration involving a four-levels dielectric medium. The probe beam engages with a cavity containing a four-level dielectric medium. By adjusting the parameters of the driving fields, the photonic spin shift can be controlled to exhibit either positive or negative values. The maximum values of the spin hall shift is in the range of \(- 200\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le 200\lambda\) with the incidence angle (\(\theta _{i}\)= 1.2 radian and 3 radian ) and the minimum values is reported as \(\pm 24.62 \lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 24.66\lambda\) against the probe field detuning (\(\Delta _{p}=0\gamma\) and \(\Delta _{p}=14\gamma\)). The results hold significant potential for use in fields like sensing devices, spin-based electronics, magnetic storage and quantum information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photonic spin hall effect (PSHE) takes place, when an electric current flowing through a material generates a perpendicular spin current due to the interaction between spin and orbital motion. This process leads to the buildup of spins oriented in opposite directions on either sides of the material1. The spin-orbit interaction causes differences in the transverse forces acting on particles with spin-up and spin-down states, while they move through the electronic potential. This leads to a transverse displacement of the particles, referred to as the PSHE2. In PSHE, right circularly polarized and left circularly polarized components function similarly to spin-up and spin-down electrons. When interacting with the interface of a coherent medium, the left circularly polarized and the right circularly polarized photons undergo distinct shifts perpendicular to the plane of incidence as a result of spin orbit interaction3. The PSHE arises from the spin-orbit coupling of light, which causes a tiny lateral shift, effectively splitting the reflected light into two circularly polarized components. When linearly polarized light interacts with an interface, it can be considered as a superposition of right circularly polarized (RCP) and left circularly polarized (LCP) waves, each experiencing a spin-dependent separation during reflection4,5. Researchers have extensively investigated the PSHE in condensed matter systems, including semiconductors6, graphene7, topological insulators8. Among the various methods for generating and controlling spin currents, the PSHE has established a significant role since it was first identified ten years ago9,10.

Dyakonov11,12 was initially proposed the PSHE, which refers to the coupling of charge and spin currents as a result of spin-orbit interaction. The term “PSHE” was introduced by Hirsch in 1999, it is quite comparable to the typical Hall effect. where charges of differing signs gather at the edges of the sample as a result of the Lorentz force in a magnetic field. The experimental evidence was gathered later, starting with the detection of the inverse spin Hall effect, which was followed by the observation of the direct PSHE in 2003. The first experiments in this area were carried out by Fleisher’s group at the Ioffe Institute in Saint Petersburg, resulting in the initial observation of what is now known as the inverse PSHE13. The PSHE remained unobserved for 33 years until it was finally detected by two research teams in Santa Barbara, California, and Cambridge, England. These findings generated significant excitement and led to a surge of both experimental and theoretical research, resulting in hundreds of published papers14,15. This effect was investigated by Bakun and colleagues, marking the first experimental confirmation of the inverse PSHE16. In a subsequent study, Tkachuk17 noted distinct indications of nuclear magnetic resonance in the surface current. Yin18 demonstrated a large PSHE using a metasurface, a rapidly changing phase across the metasurface deflects light and a simultaneous geometric polarization rotation maintains polarization perpendicular to the new propagation direction. This geometric rotation, arising from spin-orbit interaction, results in a spin-dependent splitting of the light. In the PSHE, an electric current flowing through a material exhibiting relativistic spin-orbit coupling can produce a transverse pure spin current that is polarized orthogonally to the plane formed by the charge and spin currents. The inverse spin hall effect (ISHE) refers to the phenomenon where a pure spin current passing through a material produces a transverse charge current. The PSHE is based on the well-established anomalous hall effect (AHE), where relativistic spin-orbit coupling causes an asymmetric deviation of charge carriers based on their spin orientation19.

This study investigates the dynamics of the photonic spin Hall shift (PSHS) within a dielectric medium having four-level N-type atomic system. The results indicate that the orientation of the PSHS can be controlled to produce either beneficial or detrimental changes by adjusting the properties of the applied driving fields. Furthermore, the peak strength of the PSHS is determined by changing the angle at which light strikes the medium.

Theory and dynamics

The two layers 1,3 in atomic model consists of a mirrors having dielectric function \(\epsilon _{1,3}\) and layer 2 is four level dielectric medium having dielectric function \(\epsilon _{2}\). The thickness of mirrors is represented by \(d_{1,3}\), whereas the intracavity atomic mediums have a thickness of \(d_{2}\) as demonstrated in Fig. 1a. The dielectric medium consists of a four-level configuration having probe field \(E_{p}\) and the control fields \(E_{1,2}\), as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

The unperturbed Hamiltonian is expressed as

The modified Hamiltonian of the dielectric material is20,21.

The density matrix method is employed to evaluate the coherence aspect of the probe field22.

where \(U^{+}\)( \(U^{-}\)) denotes the creation (annihilation) operator associated with decay processes23 and indicates the decay rates between different atomic states. The steady-state coherence solution for the probe field is outlined below.

where \(H_{1-4}\) are given as:

The susceptibility of the dielectric medium is \(\chi _{die}=\frac{2N|\varrho _{die}|^{2}}{\epsilon _{0}\hbar R_{p}}\rho _{13}\). Here N is atomic number density, \(\varrho _{die}\) is dipole moments, \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{die}\) is probe field coherence. The dielectric susceptibility is expressed as24

The permittivity of the dielectric medium is \(\epsilon _{2}=1+\chi _{die}\). The light beam approaches the cavity situated between the mirrors at an incident angle \(\theta _i\) from the vacuum. The light can either reflect or transmit through the structure. As shown in Fig. 1a, The incoming beam’s left and right handed circular polarization components are separated spatially along a direction perpendicular to the plane of incidence. This lateral shift, referred to as the Photonic Spin hall Effect (PSHS), is an optical phenomenon influenced by polarization, resulting in photons with opposite helicities diverging because of the interplay between their spin and orbital angular momentum. This phenomenon can be viewed as the optical counterpart of the electron spin hall shift. For the three-layer setup under examination, the reflection coefficients are denoted as \(r_p\) for TM polarization and \(r_s\) for TE polarization in the following way25:

where \(r^{12.23}_{p}\) and \(r^{12.23}_{s}\) is the Fresnel’s reflection coefficient at the 1,2 and 3 interfaces are given by

where \(k_{1z}=\sqrt{k_{o}\epsilon _{1}-k^{2}_{x}}\), \(k_{2z}=\sqrt{k_{o}\epsilon _{2}-k^{2}_{x}}\) and \(k_{3z}=\sqrt{k_{o}\epsilon _{3}-k^{2}_{x}}\) is the wave vector within the respective layers and \(k_{x}=\sqrt{\epsilon _{1}}k_{o} sin\theta _{i}\). Where \(k_{o}=2\pi /\lambda\) denotes wave vector.

As shown in Eqs. (10) and (11), the reflection coefficients depend on the dielectric medium’s permittivity, denoted as \(\epsilon _{2}\), which can be actively modified by changing \(\chi _{die}\). This variation results in a tunable Photonic Spin hall shift (PSHS) for incident light. Once the dielectric susceptibility is known, the PSHS can be calculated using the Fresnel reflection coefficients. The transverse spin shift, represented by \(\delta ^{L}{p}\) and \(\delta ^{R}{p}\), is defined based on the reflection coefficients associated with the three layers 1,2 and 3 are26.

Here \(k_{1}=\sqrt{\epsilon _{1}}k_{0}\) and \(\omega ^{2}_{o}\) is radius of the incident beam’s waist.

Findings and analysis

In this section, the transverse spin hall shift (PSHS) of the reflected probe beam is examined within a four-layer dielectric medium. The results are obtained from Eq. (16), which describes the transverse spin shift related to the three-layer atomic configuration. Furthermore, the photonic spin shift can be adjusted to yield both positive and negative values, depending on the parameters of the applied fields.

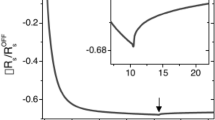

The PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) in relation to the detuning \(D_{1}/\gamma\) of the control field is illustrated in Fig. 2. The \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) is decreasing and then increases function of negative detuning and at the resonance point of the detuning \(D_{1}=0\gamma\), the PSHS is found to be \(\pm 36.98 \lambda\), while the maximum value of PSHS is \(\pm 37.0 \lambda\) at \(D_{1}= 1\gamma\) and then decreases up to \(D_{1}= 10\gamma\) is depicted in Fig. 2a,b.

The PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) in relation to the detuning \(D_{2}/\gamma\) is illustrated in Fig. 2. The \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) is decreasing function of negative detuning and the high value of PSHS is \(\pm 36.50 \lambda\) at \(D_{2}=-10\gamma\). At the resonance point of the detuning \(D_{2}=0\gamma\), the PSHS is found to be \(\pm 36.30 \lambda\), while the minimum value of PSHS is \(\pm 36.20 \lambda\) at \(D_{2}= 5\gamma\) is depicted in Fig. 3a,b.

Figure 4 examine the relationship between PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) and the probe field detuning \(D_{p}/\gamma\). The PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}{p}\) is decreases and then increases with \(D_{p}/\gamma\). The high value of PSHS is \(\pm 24.66 \lambda\) at \(D_{p}= -12\gamma\) and small PSHS is investigated to be \(\pm 24.62\lambda\) at resonance point \(D_{p}=0\gamma\) is seen in Fig. 4a,b.

Figure 5, explain the PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) versus decay rate \(\Gamma _{31}/\gamma\). The \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) is gradually increases and then decreasing function of \(\Gamma _{31}/\gamma\). The high PSHS is recorded to be \(\pm 31.72 \lambda\) at \(\Gamma _{31}=1.5\gamma\) and the small PSHS is \(\pm 31.62 \lambda\) at \(\Gamma _{31}=0\gamma\) as displayed in Fig. 5a,b.

Figure 6 explicates the PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) is strong oscillation function of control field phase \(\phi _{2}\). The maximum value of \(\delta ^{L,r}_{p}\) is noted to be \(\pm 127.0 \lambda\) at \(\phi _{2}\)= 0 radian, 3 radian and 7 radian. While the small PSHS is \(\pm 127.0 \lambda\) at \(\phi _{2}\)= 1.1 radian, 4.1 radian as displayed in Fig. 6a,b.

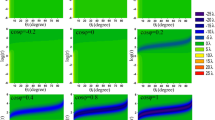

Figure 7 elucidates the PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) with angle of incidence \(\theta _{i}\). The \(\delta ^{L}_{p}\) is increasing and then decreasing function of \(\theta _{i}\) and touching the swamping point at \(\theta _{i}\)= 1.5 radian and tuned to negative value of PSHS, then its value decreases and then increases and touches the swamping point again at \(\theta _{i}\)= 3.2 radian. The value of PSHS lies in the range \(- 200\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le 200\lambda\) at \(\theta _{i}\)= 3 radian and 1.2 radian as displayed in Fig. 7a. The value of PSHS at \(\theta _{i}\)= 0 radian is minimum (touches the swamping point) and then increases upto \(\theta _{i}\)= 0.2 radian. The PSHS again decreases and touches the swamping point at \(\theta _{i}\)= 1.5 radian and increases with increases \(\theta _{i}\) upto \(\theta _{i}\)= 3 radian, then decreases and touches swamping point at \(\theta _{i}\)= 3.2 radian. The value of PSHS lies in the range \(- 200\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le 200\lambda\) at \(\theta _{i}\)= 1.2 radian and 3 radian as displayed in Fig. 7b.

Figure 8 illustrated the effect of PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) versus Rabi frequency \(R_{1}/\gamma\). The PSHS \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) slowly decreases with increases the \(\Omega _{1}/\gamma\) upto \(\Omega _{1}=24\gamma\) and then increases upto \(\Omega _{1}=40\gamma\). The PSHS is recorded in the range \(\pm 136.5\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 139.3\lambda\) at \(R_{1}=12,24\gamma\) at \(R_{1}=\gamma\) as depicted in Fig. 8a,b.

Figure 9 elucidates the effect of PSHS\(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) is increasing and then decreasing function of Rabi frequency \(R_{2}/\gamma\). The maximum and minimum value of \(\delta ^{L,R}_{p}\) lies in the range of \(\pm 126.6 \lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 127.6 \lambda\) at \(R_{2}=0,10\gamma\). as displayed in Fig. 9a,b.

Conclusion

The PSHS of a probe field induced by using a four levels dielectric medium. The incident photons with opposite spins become spatially separated along the transverse axis due to the coupling between their spin and orbital angular momentum. The probe beam is introduced into a cavity containing a four-level dielectric medium, allowing the photonic spin shift to be tuned to either positive or negative values by altering the parameters of the driving fields. The larger values of the spin hall shift is in the range of \(- 200\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le 200\lambda\) with incidence angle and smaller values of the spin hall shift is reported to be \(\pm 24.62 \lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 24.66\lambda\) against the probe field detunng. The value of PSHS lies in ranges \(\pm 136.5\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 139.5\lambda\) and \(\pm 126.6\lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 127.6 \lambda\) with control fields Rabi frequencies and with decay rate its value lies in range of \(\pm 31.62 \lambda \le \delta ^{L,R}_{p}\le \pm 31.72 \lambda\). These applications utilize the PSHE capability to create, control, and transform spin currents, facilitating advancements in computing, memory, and sensing technologies.

Data availability

Data was associated with this manuscript on reasonable request from the corresponding author

References

Sinova, J., Valenzuela, S. O., Wunderlich, J., Back, C. H. & Jungwirth, T. Spin Hall effects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213 (2015).

Hirsch, J. E. Spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1834 (1999).

Kim, M. et al. Spin Hall effect of light: from fundamentals to recent advancements. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200046 (2023).

Kim, M. et al. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200046 (2022).

Shah, M., Anwar, M. S., Asgari, R. & Xianlong, G. Phys. Rev. B 109, 235418 (2024).

Kato, Y. K., Myers, R. C., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Observation of the spin Hall effect in semiconductors. Science 306, 1910 (2004).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801 (2005).

Abbas, M., Wang, Y. & Wang, F. Tuning the Photonic Spin Hall Effect through vacuum-induced transparency in an atomic cavity. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 196, 116292 (2025).

Day, C. Phys. Today 58(2), 17 (2005).

Wunderlich, J., Kaestner, B., Sinova, J., & Jungwirth, T. (2004) arXiv:cond-mat/0410295.

Hirsch, J. E. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1834 (1999).

Bakun, A. A., Zakharchenya, B. P., Rogachev, A. A., Tkachuk, M. N. & Fleisher, V. G. Pis’ma. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz.40, 464 (1984).

Tkachuk, M. N., Zakharchenya, B. P., Fleisher, V. G. & Eksp, Z. Teor. Fiz. Pis’ma 44, 47 (1986).

Kato, Y. K., Myers, R. C., Gossard, A. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Science 306, 1910 (2004).

Wunderlich, J., Kaestner, B., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 047204 (2005).

Bakun, A. A., Zakharchenya, B. P., Rogachev, A. A., Tkachuk, M. N. & Fleisher, V. G. Pis’ma. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz.40, 464 (1984).

Tkachuk, M. N., Zakharchenya, B. P., Fleisher, V. G. & Eksp, Z. Teor. Fiz. Pis’ma 44, 47 (1986).

Yin, X., Ye, Z., Rho, J., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. Photonic spin Hall effect at metasurfaces. Science 339, 1405–7 (2013).

Nagaosa, N., Sinova, J., Onoda, S., MacDonald, A. H. & Ong, N. P. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82(2), 1539 (2010).

Khan, N., Bacha, B. A., Iqbal, A., Rahman, A. U. & Afaq, A. Gain-assisted superluminal propagation and rotary drag of photon and surface plasmon polaritons. Phys. Rev. A 96(1), 013848 (2017).

Khan, Q. et al. Conductivity Dependent Sensitivity of the Surface Plasmon Polariton Waves at the Interface of Metal and Dielectric Using Wavelength Interrogation. Plasmonics 19, 1969–1975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-023-02134-y (2024).

Bacha, B. A. & Jabar, M. S. A. The event cloaking from a birefringent medium via Kerr nonlinearity. J. Opt. 20, 095703 (2018).

Khan, Q., Abukhadra, M. R. & El-Sherbeeny, A. M. Coherent manipulation of the surface plasmon resonance sensing at the dielectric-graphene interface under Cross-Kerr nonlinearity effect. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 618(15), 172858 (2025).

Bakht Amin Bacha. Saeed Ahmad, Rashid Ahmad, Coherent manipulation of vectorial soliton beam in sodium like atomic medium. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 182, 114856 (2024).

Wan, R.-G. & Zubairy, M. S. Controlling photonic spin Hall effect based on tunable surface plasmon resonance with an n-type coherent medium. Phys. Rev. A 101, 033837 (2020).

Xiang, Y., Jiang, X., You, Q., Guo, J., & Dai, X. Enhanced spin Hall effect of reflected light with guided-wave surface plasmon resonance, Photon. Res., PRJ 5, 467 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502). Therefore, we would like to thank Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University for supporting this work.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qaisar Khan did the primary work and performed all the simulation. Ibrahim Aldayel and Meraj Ali Khan helped in writing draft. Majid Khan reviews the paper. All authors read the article and helped in improving it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, Q., Al-Dayel, I., Khan, M.A. et al. Manipulation of the photonic spin hall shift using the four levels atomic system. Sci Rep 15, 30142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15201-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15201-7