Abstract

The mine ventilation system is a vital component in ensuring mine safety, and optimizing it is crucial for reducing energy consumption and improving efficiency. However, traditional optimization methods face limitations when applied to complex mine ventilation systems, making it challenging to achieve optimal results. This paper presents an optimization method for mine ventilation systems utilizing an enhanced Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO). Several enhancement strategies have been made to address issues such as uncoordinated global search, limited local exploitation, and slow convergence speed in the standard DBO, including chaotic initialization, random walk strategy, and cross-strategy. The Strategy-Combined Dung Beetle Optimizer (SCDBO) is used to optimize mine ventilation systems by reducing energy consumption through improved air distribution and resistance management within the network. Experimental results show that SCDBO can effectively reduce the energy consumption of mine ventilation systems, achieving a 27% energy savings and providing a practical new approach for optimizing mine ventilation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mine ventilation system is essential for maintaining safety and efficiency in mining operations. Its main function is to provide fresh air underground, disperse and remove hazardous gases, and regulate temperature and humidity, ensuring a safe and healthy environment for miners1,2. Since the 1950s, mechanical ventilation systems have been used in China’s metal mines. However, the efficiency of ventilation fans has consistently fallen below optimal levels. Low fan efficiency mainly results from design redundancy, untimely regulation, and complex airflow paths, leading to their consistent failure to reach rated energy efficiency during actual operation. Data shows that these fans operate at about 40% efficiency, which is well below the target. Additionally, ventilation energy use accounts for roughly one-third of overall mine energy consumption, with electricity for ventilation making up around 70% of that. In large mines, the installed power of fans can reach several thousand kilowatts, resulting in annual ventilation costs of millions of yuan (approximately 40-80 thousand USD). Traditional ventilation design and management methods no longer meet the higher standards for efficiency and safety in modern mines. As a result, optimizing mine ventilation systems has become a crucial and urgent issue in the field of mining engineering3.

There are significant differences in the airflow requirements of various mine areas at different times of the day. These differences usually result from the following: multiple mining faces operating simultaneously, which requires dynamic adjustment of ventilation airflow distribution; toxic and hazardous gas (e.g., methane, CO) concentrations fluctuate over time and area, necessitating temporary increases in airflow to ensure safety; and frequent changes in operation schedules and equipment operating cycles, leading to regular adjustments in airflow needs.

These factors that directly affect the organization of mine airflow make fixed airflow design no longer suitable for the flexibility requirements of modern mine operations. Failure to dynamically allocate airflow according to actual demand will lead to safety hazards due to insufficient air supply in some areas and wasteful energy consumption in other areas. Consequently, it is crucial to investigate intelligent optimization algorithms capable of addressing ’variable air demand,’ which can enhance ventilation efficiency and energy conservation in mines.

In recent years, with the widespread application of intelligent algorithms, researchers have introduced them into the field of mine ventilation, achieving remarkable results. Lowndes et al. utilized genetic algorithms to optimize the ventilation system, evaluating and selecting the most cost-effective solution during the process, which successfully minimized the energy consumption of fan operation4. V. R. Babu Particle swarm optimization technique was applied to obtain the optimum rotational speed of the mine ventilation fan, and the optimized solution was used in underground coal mines to obtain better fan performance and lowest operating cost5. T. Fogarty and Z. Y. Yang utilized genetic methods to optimize the mine ventilation system by determining the optimal fan position to minimize the fan’s operating cost6. In China, Wei used a penalty function to transform the model constraint equations into a penalty function to establish a mathematical model of nonlinear unconstrained optimization and performed airflow optimization through the bionic ant colony algorithm7. Chen et al. introduced a novel approach that integrates an improved differential evolution algorithm with a critical path-driven methodology grounded in multivariate decoupling principles. This hybrid framework aims to improve the efficiency of finding optimal global outcomes by strategically separating interdependent variables within the solution space8. Si et al. introduced a greedy search strategy based on the study of the standard DE algorithm, and they also proposed an improved differential evolution algorithm using the greedy search strategy to solve the nonlinear optimization model of the ventilation network9.

In the field of mine ventilation optimization, a popular approach is to establish corresponding objective functions tailored to the specific needs of actual ventilation. This involves applying intelligent optimization algorithms and computer software technology to optimize the mine ventilation system by searching for an optimal solution to the objective function and generating an optimal regulation scheme. Wu et al. enhanced the fireworks optimization framework by embedding a novel opposition-based elite learning mechanism, which strengthens the algorithm’s search in spatial neighborhoods and thus improves the global search capability10. Shao et al. developed a hybrid computational framework by synergistically merging the stochastic exploration capabilities of simulated annealing with the swarm intelligence principles of an improved particle swarm optimization technique, thereby establishing a robust multi-algorithm integration paradigm for complex optimization challenges11. Song integrated an enhanced particle swarm optimization algorithm with a forbidden search algorithm. The purpose of this integration was to enhance the algorithm’s convergence velocity and precision12. Han proposed a sparrow search algorithm with multi-strategy fusion and developed an MSSA-based optimization search and solution method for the wind volume objective function13. Current research on mine ventilation optimization mainly uses intelligent algorithms, but each method has different strengths and limitations in managing complex ventilation networks. Genetic Algorithms (GA) effectively solve discrete optimization problems but encounter slow convergence and high computational costs in large networks. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) shows fast convergence; however, it often gets stuck at local optima when optimizing high-dimensional resistance parameters. Differential Evolution (DE) performs well in global exploration but has difficulty with nonlinear constraints common in ventilation safety rules. Hybrid strategies reduce individual weaknesses but add complexity due to hyperparameter tuning.

In summary, although current research has made some progress, there are shortcomings in terms of convergence speed, global optimality, and multi-objective synergy. With the development of artificial intelligence, hybrid algorithms that integrate multiple strategies have emerged as a research trend, enabling more robust and precise ventilation optimization under complex and variable working conditions. In this study, a hybrid strategy-combined dung beetle optimizer (SCDBO) method is proposed to address the nonlinear and constrained characteristics of mine ventilation systems, aiming to solve these problems. This study aims to address these issues by proposing a hybrid SCDBO approach tailored to the nonlinear, constrained nature of mine ventilation systems.

This study presents an in-depth analysis of the mine ventilation network, focusing on the challenges of variable wind demand and excessive ventilation energy consumption in the coal mine ventilation system. It aims to develop a wind control scheme that can achieve wind distribution according to demand and minimize ventilation operation costs. The outer-point penalty function method is employed to address the issue of nonlinear constraints, thereby enabling the formulation of a nonlinear unconstrained mathematical optimization model specifically designed for the mine ventilation network. SCDBO is introduced. Optimization simulation experiments were conducted based on this nonlinear, unconstrained optimization model of the ventilation network. These experiments were designed to confirm the practicality and superiority of the SCDBO when applied to optimizing airflow within the mine ventilation network.

Mathematical model for mine ventilation network optimization

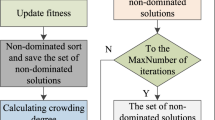

Figure 1 depicts the flowchart of the mine ventilation network optimization model, which shows the complete optimization framework from problem input to optimal solution generation in a visual form.

Constraints

To create a mathematical optimization model aimed at distributing air volume within mine ventilation networks while minimizing total energy consumption, the model must meet the following constraints14:

-

The law of airflow balance: At any point in time and any branch node in the ventilation network, the inflow air volume is always equal to the outflow air volume. The formula for the law is as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} & \sum _{\textrm{j}=1}^N a_{i j} Q_j=0, i=1,2, \cdots , J-1 \end{aligned}$$(1)$$\begin{aligned} & a_{i j}=\left\{ \begin{array}{c} 1, \text{ The } \text{ air } \text{ flow } \text{ of } \text{ branch } j \text{ flows } \text{ into } \text{ node } i \\ -1, \text{ The } \text{ air } \text{ flow } \text{ of } \text{ branch } j \text{ flows } \text{ out } \text{ of } \text{ node } i \\ 0, \text{ Node } i \text{ is } \text{ not } \text{ an } \text{ endpoint } \text{ of } \text{ branch } j \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$(2)

\(N_{\text{ and } } J_{\text{ represent } \text{ the } \text{ ner } }\) number of branches and nodes in the ventilation network, respectively. \(Q_{\textrm{j}}\) is the airflow in branch \(\textrm{j}, \textrm{m}^3 / \textrm{s}\).

-

The resistance law: The ventilation pressure of the branch is equal in magnitude but opposite in direction to the ventilation resistance.

$$\begin{aligned} H_j=R_j\left| Q_j\right| Q_j \end{aligned}$$(3)

where \(H_j\) represents the air pressure in branch j, Pa. \(R_j\) represents the resistance of branch \(\textrm{j}, \textrm{kg} / \textrm{m}^7\). In mine ventilation tunnels, environmental parameters and ventilation equipment also affect the ventilation network system. The following equation is satisfied in any ventilation tunnel:

where \(H_j^{\prime }\) is the pressure drop in branch \(\textrm{j}, _{y j}\) represents the change in resistance value during the resistance adjustment process in branch \(\textrm{j}, ^{n g}\) represents the natural air pressure in branch j, and \(H_f\) represents the fan pressure in branch j.

-

Pressure balance law: At any point in time and for any loop in the ventilation network, the algebraic sum of the pressure drops of all branches in the loop is equal to zero under the set forward flow direction15.

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j=1}^N b_{r j}\left( H_j+H_{r j}-H_{r j}-H_{f j}\right) =0, k=1,2, \cdots S \end{aligned}$$(5)where \(b_k\) represents the k-th independent loop in the independent loop matrix. S represents the number of independent loops, \(\textrm{S}=\textrm{N}-\textrm{J}+1\), and \(b_{k j}\) is an independent circuit matrix.

$$\begin{aligned} a_{i j}=\left\{ \begin{array}{c} 1, \text{ The } \text{ airflow } \text{ of } \text{ branch } j \text{ flows } \text{ into } \text{ node } i \\ -1, \text{ The } \text{ airflow } \text{ of } \text{ branch } j \text{ flows } \text{ out } \text{ of } \text{ node } i \\ 0, \text{ Node } i \text{ is } \text{ not } \text{ an } \text{ endpoint } \text{ of } \text{ branch } j \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$(6)

-

Upper and lower limits of ventilation variables

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{c} Q_{j \min }<Q_j<Q_{j \max } \\ H_{j \min }<H_j<H_{j \max } \\ H_f<0.9 H_{f \max } \\ W_{\text{ out } } / W_{\text{ in } } \ge 70 \% \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$(7)Minimizing the total power consumption of the ventilation network fans is the optimization objective of the ventilation network model, which is expressed as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \min W=\sum _{f=1}^{N_f}\left| H_f\right| \left| Q_f\right| \end{aligned}$$(8)where W denotes the total power of the fan, \(\textrm{kW}\). \(N_f\) denotes the number of fan branches in the ventilation network. \(H_f\) and \(Q_f\) denote the air pressure and air volume of the fan branches, \(\textrm{Pa}\), \(\mathrm {m^3/s}\), respectively16.

Unconstrained optimization model

Considering the complex, dynamic, and nonlinear characteristics of the coal mine ventilation network, during the ventilation optimization process, parameters such as air volume and air pressure in any branch may fluctuate due to changes in other variables. Therefore, additional constraints and penalties are required for the external anomalies of the feasible domain, so the penalty function method for outer point is used for unconstrained optimization modeling17, as shown in Eq. (9):

where \(\ln\) denotes the natural logarithm. \(\alpha , \beta\) and \(\gamma\) denote strictly ordered positive sequences.

Experimental methods

Improvement of dung beetle algorithm

The Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) is a novel population intelligence optimization algorithm first proposed by Jiankai Xue and Bo Shen in 202218. DBO was selected due to its biologically inspired behavioral mechanisms, which allow for diversified search processes. Compared to traditional methods like PSO and DE, DBO incorporates five distinct behaviors (e.g., ball rolling, dancing, and foraging), naturally balancing between exploration and exploitation. However, the DBO algorithm has some drawbacks, including low initial population diversity and a tendency to become trapped in local extreme values. The Dung Beetle optimizer does not balance global search in the early stages of the algorithm and local exploration in the late stages, resulting in a decrease in the accuracy of the solution19. To address this issue, the present study improves it through hybrid strategies, making SCDBO particularly suitable for complex ventilation optimization tasks.

-

Initialize the dung beetle population using Piecewise chaotic mapping

Since the basic dung beetle search algorithm’s initial population is randomly generated, the uniform distribution of individuals’ initial positions in the search space cannot be guaranteed, which impacts the algorithm’s search speed and optimization performance. Piecewise mapping is introduced in the initialization process of the improved dung beetle algorithm to enhance the initial population’s traversability.

The principle of piecewise mapping refers to utilizing segmented functions in order to describe an integral function. It does this by dividing the definition domain of the overall function into several subintervals and defining the corresponding expression on each subinterval. In this way, the overall function can be obtained by combining the expressions on these subintervals. The formula is as follows:

The parameter p of the segmented chaotic mapping in this study is set to 0.5-0.9, which is screened by pre-experimentation.

-

Perturbation of Dung Beetle Ball Rolling Behavior using Random Walk Strategy

The dung beetle ball-rolling behavior, as the first-stage behavior of the dung beetle algorithm, searches for the global position and determines the optimization ability of the entire algorithm. This improvement uses the random wandering strategy to perturb the dung beetle ball rolling behavior stage. To prevent increasing the complexity of the algorithm, it is set that when the optimal value of the dung beetle algorithm remains unchanged for five iterations, the random wandering strategy is used.The formula for the random wandering strategy is as follows:

Take a random function r(t) as in \(\textrm{Eq}(12)\) :

Since the action trajectory of the intelligent algorithm has a specific range, the position of the algorithm cannot be updated directly with the above equation. To ensure that the algorithm walks within a specific range, it needs to be normalized, as shown in equation (13):

where \(\quad X_i^t\) is the position of the i-th dung beetle in the t-th iteration; \(a_i\) and \(b_i\) are the minimum and maximum values of the i-th-dimensional random wandering variable, respectively; \(C_i^t\) and \(D_i^t\) are the minimum and maximum values of the i-th-dimensional random wandering variable in the t-th iteration, respectively.

The random walk perturbation is triggered when the best fitness value of the population remains unchanged for 5 consecutive iterations. This threshold was determined through sensitivity testing to balance between avoiding premature stagnation and preserving convergence stability.

-

Longitudinal and transversal crossover strategies to perturb dung beetle rolling behavior

The longitudinal crossover strategy includes both horizontal and vertical crossover. Population search using transverse crossover can reduce blind spots in the search and enhance the algorithm’s global search capability20. The premature convergence of many population-based intelligent search algorithms is often attributed to specific stagnant dimensions within the population. A vertical crossover can help address these stagnant dimensions, allowing the algorithm to escape from local optima. Furthermore, crossover operations can increase the diversity of the population, which further enhances search effectiveness. The vertical and horizontal crossover strategies also involve a competitive process, where the resulting offspring are compared with their parents to ensure that the update results in an improved direction. Horizontal crossover and vertical crossover are performed sequentially, with the two interactions enhancing the algorithm’s solution accuracy and speeding up convergence.These two crossover operations are briefly described below. A horizontal crossover is an arithmetic crossover between two different individuals operating in all dimensions. The individuals in the population are first randomly paired, and then a transverse crossover is performed between the two paired individuals. Assume that \(S M_{i 1}\) and \(S M_{i 2}\) are the paired parent individuals whose children are \(S M_{i 1}^{h c}\) and \(S M_{i 2}^{h c}\) are generated by the following equation:

where \(S M_{i 1 j}\) and \(S M_{i 2 j}\) denote the j -th dimension of \(S M_{i 1}\) and \(S M_{i 2}, \textrm{j}=1,2, \cdots , \textrm{D}, S M_{i 1 j}^{h e}\) and \(S M_{i 2 j}^k\) are the j -th dimensions of the offspring generated by the horizontal crossover of \(S M_{i 1 j}\) and \(S M_{i 2 j}\) in the j-th dimension. The generated offspring are each compared with their parents, and the individuals with smaller objective function values are retained.

A longitudinal crossover is an arithmetic crossover involving all individuals, applied across two different dimensions. Each individual performs a longitudinal crossover to update only one of these dimensions, leaving the others unchanged. This allows the stagnant dimension to potentially escape the local optimum without disrupting another dimension that might already be optimal. Assuming that the current pair performs a longitudinal crossover and randomly selects two dimensions j1 and j2, the j1th dimension of its offspring is obtained from Eq. (16), and the other dimensions are kept the same as the parent’s \(S M_i\) :

where r is a uniformly distributed random number in the range (0, 1). The generated offspring are compared with their parents, and individuals with smaller objective function values are retained. The longitudinal crossover strategy is added at the end of the dung beetle algorithm to perturb the entire population of dung beetles. Again, to avoid increasing the complexity of the algorithm, this improvement introduces a longitudinal and transversal crossover strategy factor pv, when \(\textrm{r}<\textrm{pv}\) :

where t is the current iteration number and M is the total iteration number.

When r is greater than pv, the vertical and horizontal crossover strategy is used, and when r is less than pv, this iteration skips both the vertical and horizontal crossover strategy.

All parameter settings were fine-tuned using existing literature or through pilot experiments to maximize convergence accuracy and solution robustness within the specific constraints of mine ventilation optimization.

Experimental model

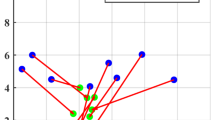

As shown in Fig. 2, the ventilation network topology of the experimental model is constructed using the ventilation network topology of the underground working face of a coal mine, which has a good experimental reference value20. Each color of the line represents an independent circuit. This model has a total of five independent circuits. The ventilation experiment includes 12 nodes, 16 branches, and 5 independent circuits. The air inlet and air outlet are atmospherically connected, represented by pseudo-branches of No. 16, and the wind resistance is zero.

Table 1 displays the basic parameters of the ventilation network, including the distribution of wind resistance and the distribution type of each branch. The values are based on a combination of practical mine design parameters and empirical data from a referenced coal mine case. In an actual mine ventilation system, due to the limitations of the roadway environment and other conditions, it is not possible to realize the adjustability of each branch. The experimental model also refers to this factor; combined with the experimental model of the network ventilation design, it takes branches 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14 as adjustable branches. The air-using branches in the ventilation network are branches 7, 8, and 9, and their target air demand is \(8m^3/s\), \(21m^3/s\), and \(21m^3/s\), respectively.

The ventilation network contains five linearly independent loops, with their distributions shown in Table 2. Counterclockwise is the positive direction of the loop; negative signs in the table indicate airflow opposite to this direction.

According to the improved dung beetle algorithm, the experiments in this study set the population size to 80, the number of iterations to 100, and the definition domain to [0,1]. In addition to testing the effectiveness and superiority of SCDBO applied to ventilation network airflow optimization, this study employs DBO, POA, and SSA to conduct a comparative experimental analysis, aiming to obtain more comprehensive results. The initial parameters of DBO, the Pelican Optimization Algorithm (POA), and the Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA) are set according to references18,21,22. The parameters of SCDBO were tuned to strike a balance between convergence speed and solution accuracy under the given mine ventilation scenario. The parameters of DBO, POA, and SSA were adopted from their respective foundational papers and adjusted via grid search within acceptable ranges based on pre-testing.

Matlab 2024 b was used to program the software for mine ventilation optimization. Based on the experimental ventilation network optimization model, simulation experiments were conducted using the four algorithms mentioned earlier.

Results and analyses

The four methods(SCDB0, DBO, POA, SSA) were repeated 30 times for comparison. The running results are shown in Fig. 3.

From Fig. 3,we see that the optimal solution and average solution of SCDBO are the smallest, 17.41 kW and 17.67 kW, respectively. This demonstrates that this algorithm performs the best and effectively reduces the system’s energy consumption compared to three other algorithms, which significantly meets the target demand of the mine ventilation network’s on-demand air distribution and energy-saving optimization.

Regarding the convergence time of the optimization, the DBO-based airflow optimization of the ventilation network has the fastest convergence speed, with an average convergence time of only 12.31 seconds. The convergence time of SCDBO is 12.37 s, while the convergence times for POA and SSA are 15.60 s and 16.21 s, respectively. The convergence time of SCDBO has a greater advantage compared with POA and SSA. Although a certain amount of time cost has been added based on SCDBO, compared to the time required for regulating the mine ventilation system, the increased time cost of SCDBO will not have any impact on the airflow optimization and regulation process of the mine ventilation network.

Meanwhile, the iterative curves of ventilation network optimization for the four algorithms within the same coordinate system are shown in Fig. 4.

As shown in Fig. 4, the SCDBO algorithm rapidly reduces the objective function value in the early iterations, with the iteration curve decreasing the fastest, escaping the local optimal solution, and then stabilizing after about 20 iterations, with the optimal power decreasing to 17.4 kW. The DBO algorithm is the second fastest, while the other two algorithms converge at a relatively slower rate. At the end of the iterations, the objective function values of all the algorithms stabilized. Among them, the SCDBO algorithm achieves the lowest objective function value and performs the best in this experiment. In terms of the smoothness of the curve, the SCDBO and DBO algorithms show better stability during the iteration process, with less fluctuation in the objective function value. The standard deviations of POA and SSA reached 1.25 and 1.10, respectively; however, the SCDBO’s standard deviation over 30 runs was 0.42 kW, compared to DBO’s 0.87 kW, confirming superior stability.

Table 3 displays the airflow of each branch before and after optimization. Among them, SCDBO and DBO ensure that the airflow of the air-using branch is the minimum of the central ventilator. In the case of natural air distribution, the fixed air volume delivered and the air pressure of the fan branch are \(107 m^3/s\) and 803.21 Pa, respectively, and the total power consumption of ventilation is 85.94 kW. Compared with natural air distribution, the ventilation network airflow optimization after optimizing SCDBO, DBO, POA, and SSA decreases the total power consumption of ventilation to meet the air volume requirement of the air-using branches. The total power consumption of the ventilation network optimization, based on the optimized airflow of SCDBO, DBO, POA, and SSA, decreases. The airflow optimization of the SCDBO-based mine ventilation network yields the most significant energy savings effect. The airflow and air pressure of the fan branch decrease to \(85.6 m^3/s\) and 732.74 Pa, and the total power consumption of ventilation drops to 62.74 kW, with the ventilation energy-saving rate reaching 27%. The 27% energy-saving rate achieved by SCDBO is primarily attributed to optimized airflow allocation in key high-resistance branches such as branches 3, 6, 10, and 14. By reallocating airflow more efficiently according to demand and resistance, SCDBO reduces the overall fan load. Moreover, the algorithm avoids over-ventilation in non-essential areas and only adjusts necessary branches, thereby minimizing total energy consumption without compromising airflow requirements at the working faces.

Although this study focuses on the single-objective optimization of the ventilation system energy consumption, it reveals multidimensional engineering value through deep mining analysis of the experimental data. While ensuring the core energy saving target, the optimized solution naturally meets the key safety constraints. The gas concentration in all the air-using branches is controlled to be at 55%-65% of the safety thresholds (branches 7/8/9 are respectively 0.32%/0.41%/0.28%, which are significantly below the 0.5% limit). When the wind demand fluctuates by ±15%, SCDBO still maintains an energy-saving rate of more than 25%, and the increase in convergence time is less than 8%. Its stochastic wandering strategy provides the algorithm with dynamic adaptability, effectively overcoming the limitations of a single scenario. The pre-study reveals that the framework has the potential for multi-objective expansion, laying the groundwork for the subsequent integration of real-time monitoring data to achieve multi-objective optimization.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a mathematical model to optimize the airflow distribution in mine ventilation networks, thereby reducing energy consumption. The model thoroughly considers the three fundamental laws governing mine ventilation networks, the operating constraints of the ventilator, the characteristics of the ventilator pressure curve, and the conditions necessary for safe and effective operation. By optimizing airflow in the mine ventilation network, it aims to reduce ventilation energy consumption. Then, the model is transformed using the exterior point penalty function method to transform the constraints into an unconstrained optimization model of mine ventilation airflow distribution. Then, the optimized dung beetle algorithm is proposed and solved. Finally, the original DBO algorithm and SCDBO algorithm are used to optimize the airflow of a typical mine ventilation network and are compared with POA and SSA. The simulation results demonstrate that the improved dung beetle algorithm performs effectively when compared with three other optimization algorithms. SCDBO exhibits superior global optimization ability with the lowest computational time cost. Furthermore, SCDBO effectively reduces the total power consumption of ventilation optimization, achieving a ventilation energy-saving rate of 27%, which significantly meets the target demand for on-demand air distribution and energy-saving optimization of the mine ventilation network.

Limitations and future work

Although the effectiveness of the SCDBO algorithm is verified by simulation in this study, numerous dynamic and uncertain factors exist in the actual mine ventilation system, including changes in the operating surface, real-time variations in wind resistance parameters, and unstable operating statuses of equipment. Moreover, the acquisition and feedback period of field data is long, which may affect the adjustment and response speed of the algorithm. To improve the feasibility of SCDBO applications in real projects, it can be integrated with digital twin technology in the future to enable real-time simulation and online optimization control, and an adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism can be introduced to address dynamic changes in mine operating conditions. This study focuses on single-objective energy-saving optimization and will explore the introduction of safety constraints, multi-objective joint modeling, and the online deployment of the algorithm in real mines in the future. The related software and hardware deployment conditions and arithmetic support requirements will also be further explored and verified in the future.

Data availability

The datasets uesd during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kurnia, J. C., Sasmito, A. P. & Mujumdar, A. S. Cfd simulation of methane dispersion and innovative methane management in underground mining faces. Applied Mathematical Modelling 38, 3467–3484 (2014).

Kurnia, J. C., Sasmito, A. P. & Mujumdar, A. S. Cfd simulation of methane dispersion and innovative methane management in underground mining faces. Applied Mathematical Modelling 38, 3467–3484 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Analysis of distribution method of designed air quantity in coal mine ventilation-a case study. Scientific reports 14, 10917 (2024).

Lowndes, I. S., Fogarty, T. & Yang, Z. The application of genetic algorithms to optimise the performance of a mine ventilation network: the influence of coding method and population size. Soft Computing 9, 493–506 (2005).

Babu, V. R., Maity, T. & Burman, S. Energy saving possibilities of mine ventilation fan using particle swarm optimization. In 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT), 676–681 (IEEE, 2016).

Lowndes, I. S., Fogarty, T. & Yang, Z. The application of genetic algorithms to optimise the performance of a mine ventilation network: the influence of coding method and population size. Soft Computing 9, 493–506 (2005).

Wei, G. Optimization of mine ventilation system based on bionics algorithm. Procedia Engineering 26, 1614–1619 (2011).

Chen, K. et al. Optimization of air quantity regulation in mine ventilation networks using the improved differential evolution algorithm and critical path method. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 25, 79–84 (2015).

Junhong, S., Xiaojun, W. & Xin, H. Nonlinear optimization solution of mine ventilation network based on improved de algorithm. Coal engineering 48, 64–67 (2016).

Xinzhong, W. et al. Optimization study of reverse enhanced fireworks algorithm for mine ventilation networks. Industrial and mining automation 45, 17–22 (2019).

Liangsuan, S., Zhen, W. & Changming, L. Mine ventilation optimization algorithm based on simulated annealing and improved particle swarms. Journal of System Simulation 33, 2085 (2021).

Jialin, S. Application of ipso-ts algorithm in air volume optimization of mine ventilation network. Mining Safety & Environmental Protection 49, 78–82 (2022).

zhenghua, H. Intelligent optimization and regulation of mine airflow based on sparrow search algorithm. Ph.D. thesis, Xuzhou: China University of Mining and Technology (2022).

Gabo, D., Hairong, Z. & Dong, W. Research on mine ventilation network optimization mathematical model and its algorithm. Metal mine 171–174 (2010).

Bigano, A., Proost, S. & Van Rompuy, J. Alternative environmental regulation schemes for the belgian power generation sector. Environmental and Resource Economics 16, 121–160 (2000).

Wang, J., Xiao, J., Xue, Y., Wen, L. & Shi, D. Optimization of airflow distribution in mine ventilation networks using the modified sooty tern optimization algorithm. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration 41, 239–257 (2024).

Fai, M. K. & Bui, S. S. A study of hybrid genetic algorithms for constrained optimization problems. Computer simulation 184–187 (2009).

Xue, J. & Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: A new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. The Journal of Supercomputing 79, 7305–7336 (2023).

Hu, W., Zhang, Q. & Ye, S. An enhanced dung beetle optimizer with multiple strategies for robot path planning. Scientific Reports 15, 4655 (2025).

Kun, L., Lu-lu, Z. & Hui, W. Whale optimization algorithm based on elite opposition-based and crisscross optimization. Journal of Chinese Computer Systems 41, 2092–2097 (2020).

Mirjalili, S. et al. Salp swarm algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Advances in engineering software 114, 163–191 (2017).

Trojovskỳ, P. & Dehghani, M. Pelican optimization algorithm: A novel nature-inspired algorithm for engineering applications. Sensors 22, 855 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. Z. conceived the experiment, and G. B.Y. conducted and analyzed it. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bingyan, G., Zhe, K. Optimization of mine ventilation energy consumption based on improved dung beetle algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 37582 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15263-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15263-7