Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the well-known neurodegenerative diseases. The main reason is the death of dopaminergic neurons that release dopamine in the brain region known as the Substantia Nigra pars Compacta (SNc). In this study, we developed a mathematical model of Parkinson’s disease incorporating a fractal-fractional operator with the Mittag–Leffler kernel to capture the complex, memory-dependent dynamics of the disease. We conduct a qualitative analysis to explore the existence and uniqueness of solutions and examine both disease-free and endemic equilibrium states. Stability conditions are explored using fixed-point theory and Lyapunov functions, while the dynamics are further analyzed through sensitivity analysis to identify the parameters most influential to the basic reproduction number. Additionally, chaos control is investigated using PID feedback strategies, and a Newton polynomial-based numerical method is implemented to simulate the system’s behavior. This approach enhances our understanding of Parkinson’s disease progression and offers a foundation for developing personalized therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is recognized as a prominent neurodegenerative disorder and mental health. The main reason involves the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons that are responsible for the secretion of dopamine in the brain region identified as the Substantia Nigra pars Compacta (SNc). Furthermore, the presence of Lewy bodies, which are aggregates of misfolded alpha-synuclein (\(\alpha\)-syn) protein, has been observed in the post-mortem examinations of individuals diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease1,2. The demise of neurons ensues when the \(\alpha\)-syn protein accumulates within a neuron, thereby obstructing the cellular autophagic processes3,4. As a result, the protein is released into the extracellular milieu, contributing to additional neuronal degeneration5,6. As a prion-like protein, the pathogenic \(\alpha\)-syn spreads from cell to cell7,8 and causes toxicity in recipient cells9,10. The body is protected from foreign antigens by the immune system. The central nervous system (CNS) contains innate immune cells called microglia, which continuously monitor the environment around the brain11,12 and respond to viruses immediately and non-selectively13,14. Anti-inflammatory cytokines are released when microglia are activated, protecting and warning nearby cells15. Additionally, they take quick action to absorb and eliminate misfolded \(\alpha\)-syn16,17 to stop neurodegeneration. But when inflammation is severe, active microglia might not be controlled, harming healthy neurons15.

In order to comprehend the dynamics of neurodegenerative disorders, mathematical models were used18,19. Puri and Li20, developed a model to investigate the interactions of amyloid-\(\beta\), neurons, microglia, and astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. They discovered that activated microglia are important in the development of neuropathy. Hao and Friedman described the interactions between neurons, microglia, astrocytes, amyloid-\(\beta\) aggregation, macrophages, and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins using nonlinear partial differential equations in21. To halt the disease’s course, they proposed a treatment strategy. A model explaining the accumulation of \(\alpha\)-syn within a neuron cell was proposed in22 for PD models. They determined that a lack of effective degradation mechanisms is the main reason for the accumulation of \(\alpha\)-syn. Furthermore, as demonstrated in23, they employed two models, diffusive and active \(\alpha\)-syn transmission, in both healthy and diseased axons. They observed that damaged axons exhibit \(\alpha\)-syn clumping in Lewy bodies. In24, a model was constructed to explain the connection between \(\alpha\)-syn aggregation and proteasome activity. They found that \(\alpha\)-syn aggregation is blocked when the proteasome to \(\alpha\)-syn ratio falls below a critical threshold. The study25 employs Hybrid NAR-RBFs networks integrated with fractional operators to analyze the dynamics of a complex non-linear COVID-19 model, enhancing predictive accuracy and system understanding. In26 explores computational techniques for monitoring a fractional-order type-1 diabetes mellitus model, aiming to optimize feedback design for artificial pancreas systems. The importance of using generalized fractal fractional operators to understand the complex dynamics of Chlamydia infection and vaccination strategies27, offering insights for effective disease control. The fractal-fractional model effectively captures the complex dynamics of tuberculosis prevalence28, demonstrating how sensitivity and stability analyses, combined with simulations under feasible scenarios, can guide optimized control strategies. A comprehensive understanding of disease dynamics across different infection stages29, offering deeper insights into transmission patterns and potential control measures. The piecewise hybrid fractional operator enhances the computational and stability analysis of the Ebola virus epidemic model30, accurately capturing the disease’s complex transmission dynamics and aiding in the design of effective control strategies. The use of fractional-order mathematical models to describe tumor dynamics under chemotherapy31. A reaction-diffusion model for Hepatitis B using real data from Thailand32 confirms stability, estimates \(R_0\), and evaluates vaccination and hospitalization impacts. A convex incidence model34 and a fractional-order norovirus model with vaccination and asymptomatic carriers33 further validate equilibrium stability and highlight key outbreak drivers through sensitivity analysis. For Ebola, the integration of vaccination within a Caputo–Fabrizio framework35 and a co-infection model with malaria36 both emphasize memory effects and targeted interventions. A dual-dosage vaccination model for Lassa fever37 and a fractional-order formulation using the Laplace-Adomian Decomposition Method38 enhance understanding of disease control. Similarly, fractional models address malaria with combined enlightenment and therapy strategies39, measles with strategic vaccination40, and computer virus spread41, highlighting the role of memory-based interventions. Within-host Chikungunya dynamics42 are also explored, revealing the impact of immune response on viral load and progression. In43 incorporates both singular and non-singular kernels to represent memory effects and the disease dynamics more accurately. The study emphasizes the impact of fractional parameters on disease progression, providing insights into control measures and the role of fractional operators in capturing real-world epidemiological trends. Recent research highlights the effectiveness of fractional and numerical modeling in understanding COVID-19 dynamics. It has been shown44 that a more transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variant will eventually outcompete less transmissible strains, and complete eradication is only possible when both variants have basic reproduction numbers below one. In a related work45, a fractional-order model using the Haar wavelet collocation method was employed to simulate the spread of Omicron in Pakistan, confirming model stability and identifying key parameters through sensitivity analysis. Similarly,46 applied finite difference and meshless methods to solve a COVID-19 model, yielding accurate estimates of the reproduction number and validating the model s stability. Additionally, a non-integer time fractional model developed in47 captures the long-term societal and economic impacts of the pandemic in Nigeria, emphasizing the value of fractional dynamics in representing persistent effects and some key factors related neural network for nonlinear system are also studied in48,49.

The study51 offers key insights into neurodegenerative disease dynamics, but most rely on classical models that overlook memory effects. In contrast, our fractal-fractional model incorporates both innate and adaptive immunity, capturing long-term biological feedback. This approach enhances realism, enables threshold analysis for disease control, and improves understanding of Parkinson s disease progression. The specific novelty of this model lies in its incorporation of a fractal-fractional operator with the Mittag–Leffler kernel, which captures the memory-dependent and complex dynamics of Parkinson’s disease more accurately than traditional integer-order models. Unlike previous models, it integrates both innate and adaptive immune responses under immunotherapy, providing a comprehensive framework to study the interplay between neurons, extracellular \(\alpha\)-syn, and immune cells. Additionally, the model employs advanced stability analysis and chaos control techniques, such as Lyapunov functions and PID controllers, to explore disease progression and therapeutic strategies. This approach offers a more nuanced understanding of PD pathophysiology and potential personalized treatment options. The fractal-fractional operator with a Mittag–Leffler kernel is employed to capture the memory and hereditary properties inherent in neurodegenerative processes like Parkinson’s disease. Biologically, it reflects the long-term interactions between neuronal damage and immune responses. Mathematically, the Mittag–Leffler kernel offers a more accurate representation of non-local dynamics and anomalous diffusion compared to classical exponential kernels, enhancing the model’s realism and analytical depth. One of the main challenges in this study lies in accurately capturing the complex, memory-dependent interactions between neuronal degeneration and immune responses. Additionally, implementing and solving the fractal-fractional model with Mittag–Leffler kernels requires advanced numerical techniques, posing both analytical and computational difficulties. The primary objective of this study is to develop a mathematically tractable model that captures the memory-dependent and nonlinear dynamics of Parkinson s disease by incorporating both neuronal degeneration and immune responses under immunotherapy. Specifically, the research seeks to address the following questions: (i) How do interactions between neurons, a-synuclein, and immune cells influence disease progression? (ii) Can fractional-order operators with Mittag–Leffler kernels better represent the long-term memory effects observed in neurodegenerative processes? (iii) What are the stability conditions and control strategies that can inform effective therapeutic interventions?

The research presents a unique model combining fractals, fractional calculations, and the Mittag–Leffler kernel for analyzing Parkinson’s disease. The structure includes: In “Introduction”, an overview of the study goals. “Preliminaries”, definitions of the operator used. “Model formulation” introduces a mathematical model for studying Parkinson’s disease. An in-depth examination of the proposed model is discussed in “Existence and uniqueness”. Stability analysis using the Lyapunov function is explained in “Stability analysis”. Chaos Control is explored in “Chaos control”. Numerical findings and results and discussion are in “Numerical scheme” and “Results of proposed scheme”. Summarizes findings in section “Conclusion”.

Preliminaries

In this section, we present several essential definitions that can significantly simplify the process of system analysis. Understanding these key concepts will help in grasping the complexities of the system.

Definition 2.1

50 According to the Atangana-Baleanu approach, which uses a generalized Mittag–Leffler type kernel, the fractal-fractional derivative of a function \(\mathfrak {U}\) belonging to \(\textbf{C}((a, b), \textbf{R})\) can be formulated as follows: it is fractally differentiable on the interval (a, b) with a fractal dimension \(0 < \vartheta \le 1\) and a fractional order \(0 < \varpi \le 1\).

where \(\mathbb{A}\mathbb{B}(\varpi )=1-\varpi +\frac{\varpi }{\Gamma (\varpi )}\).

Definition 2.2

50 As previously indicated, the Atangana–Baleanu technique, using a Mittag–Leffler type kernel, may calculate the fractal-fractional integral of the function \(\mathfrak {U}\) with a fractional order \(0 < \varpi \le 1\).

Model formulation

The dynamics of the interaction between neurons, extracellular \(\alpha\)-syn, and innate and adaptive immune cells are described in51. The proposed model comprises five distinct compartments: the density of functionally intact neurons, denoted as N(t); the density of neurons infected in the brain, I(t); the density of extracellular \(\alpha\)-syn, indicated as \(\alpha S(t)\); the density of activated microglia, referred to as M(t); and the density of activated T cells, T(t). The model is based on biologically informed assumptions that simplify the complex neuroimmune dynamics of Parkinson’s disease to enable tractable mathematical analysis. These include constant recruitment and decay rates for neurons and immune cells, and homogeneous mixing of compartments. While these assumptions facilitate analytical and numerical treatment, they can be relaxed in future work by incorporating time-dependent or spatially heterogeneous parameters. The parameter values were selected based on existing literature51 and calibrated to reflect biologically plausible behavior under both disease-free and endemic scenarios. Neurons and \(\alpha\)-syn capture disease spread, while microglia and T-cells reflect the innate and adaptive immune responses. The interaction terms model activation, apoptosis, and immune regulation based on established neuroinflammatory mechanisms in PD. The schematic diagram of model show in Fig. 1 the interaction terms \(\beta N \alpha S\) for neuron infection, \(ed_1I\) for \(\alpha\)-syn release, and \(a_1 I\) + a\(\alpha\) S for microglial activation reflect experimentally observed mechanisms, such as \(\alpha\)-syn propagation, neuroinflammation, and immune clearance. These terms align with prior biological studies51 and ensure the model captures critical PD dynamics, including neuronal loss and immune response modulation. Parameters value display in Table 1. The two cases in Table 1 represent distinct disease dynamics: \(R_0 < 1\) corresponds to a controlled or eradicated state, while \(R_0 > 1\) indicates disease persistence. These parameter sets were used in simulations to illustrate the model’s behavior under varying transmission intensities, enabling comparative analysis of stability and progression outcomes. The fractal-fractional operator as conceptualized within the Atangana-Baleanu framework, which is introduced in the current study, serves as an effective instrument for comprehending the dynamics of epidemics and the transmission of diseases, in addition to facilitating the modeling of complex systems and phenomena.

This set of non-linear fractal-fractional differential equations represents the updated fractional model, concerning the Atangana–Baleanu approach for values of \(0 < \varpi ,\vartheta \le 1\).

with the initial conditions

Positive bounded solutions

Given that the operations delineated in the suggested model are constrained and exhibit positive outcomes with a degree of certainty, we examine the specific conditions under which its application may be relevant to significant real-world situations. Regarding derivatives, for every \(\forall t \ge 0\), we have the following:

To find out the norm, we need to: \({\left\| \mathfrak {V} \right\| _\infty } = {\sup _{t \in {D_\mathfrak {V}}}}\left| {\mathfrak {V}\left( t \right) } \right| .\) Next, we find

then

According to52, system (3) solutions are always positive \(\forall t \ge 0\).

Equilibrium points

The model’s equilibrium points (3) are determined by setting the equations on the right side to zero. Thus, the model has a free equilibrium point.

The model endemic point is

where

The disease-free equilibrium represents a healthy brain state with no infection or immune activation, indicating successful control of pathological processes. In contrast, the endemic equilibrium reflects persistent \(\alpha\)-syn accumulation and immune activity, corresponding to sustained neuroinflammation and disease progression. These states help assess long-term outcomes under different biological conditions.

Next, we use the next-generation approach and the free equilibrium point to determine the basic reproduction number. The following matrices, F and V, are obtained by evaluating the Jacobian at the free equilibrium point:

Therefore, the matrix for the next generation is

Therefore, \(R_0\), the fundamental reproduction number, is provided by

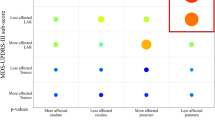

The effect of parameters on reproduction number show in Fig. 2.

Sensitivity analysis examines how variations in input parameters influence model outcomes, identifying the most impacting factors. It is widely used to improve model accuracy, prioritize interventions, and guide decision-making in complex systems. Sensitivity analysis of key parameters affecting model are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3. Parameter ranges for sensitivity analysis were chosen based on existing literature on Parkinson’s disease51. These ranges represent biologically plausible variations in key parameters. Figure 3 illustrates that parameters \(\mu _1, a_1\) and \(a_2\) have negative sensitivity indices, indicating their suppressive effect on the basic reproduction number \(R_0\), while parameters \(\beta\), e, \(\sigma\) and \(d_1\) positively influence \(R_0\). Among these, \(\beta\), e, and d1 most strongly influence R0, highlighting their critical roles in disease progression.

Existence and uniqueness

The primary objective of the analysis is to utilize fixed point theorems to establish the existence of solutions for nonlinear systems. In the realm of nonlinear functional analysis, fixed-point contractions are employed to substantiate the existence of solutions within specific systems. Within the context of Banach spaces, fixed point mappings facilitate a more profound understanding of the matter at hand. One must ascertain whether a solution exists and whether it possesses uniqueness. According to a theorem pertaining to fixed point mappings, the model represented by Eq. (3) will yield a singular solution within the interval \([0, \mathbb {T}]\). By considering Eq. (3), we may interpret it as

Mittag–Leffler kernel transforms equation into Fractal Fractional integral.

We show the basic idea behind the governing formulas (6) applying the fixed point theorem of Krasnoselski: \({\Phi }({J_1},{K_1},{L_1},{O_1},{P_1})\) as maps of contractions and \({\Psi }({J_2},{K_2},{L_2},{O_2},{P_2})\) as compact, continuous integrated elements.

Theorem 4.1

This non-linear mapping \({\Phi }({J_1},{K_1},{L_1},{O_1},{P_1}): [0,\textbf{T}]\rightarrow \textbf{R}^5\) given in (8)–(9) certify that constants satisfy the Lipschitz contractive requirement \({Q}_{{J}}\), \({Q}_{{K}}\), \({Q}_{L}\),\({Q}_{{O}}\),\({Q}_{{P}}\) \(>0\)

Proof

Examine \({\Phi }({J_1},{K_1},{L_1},{O_1},{P_1}) : [0,\textbf{T}]\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^5\) in the form of a completely normed space

(i) Initially, we will show that the details of a mapping of contractions is \({\Phi }({J_1},{K_1},{L_1},{O_1},{P_1})\). For N and \({\bar{N}}\)

where \({Q_J} = \left\| {\left( {\beta \left\| {\alpha S} \right\| + {a_1} + {a_2} + \mu } \right) } \right\|\). By employing this method, we get

where \({Q_K} = \left\| {{d_1} + {a_1} + {a_2}} \right\| ,\) \({Q_L} = \left\| {{a_1} + {a_2}} \right\| ,\) \({Q_O} = \left\| {{\mu _2}} \right\| ,\) \({Q_P} = \left\| {{\mu _3}} \right\| .\)

The following is clearly derivable for \({\Phi }(N,I,\alpha S,M,T)\).

where

\(Q=\max [Q_{{J}},Q_{{K}},Q_{{L}},Q_{{O}},Q_{{P}}]<1\) ensures the Lipschitz constant. In this sense, the operator \({\Phi }({J},{K},{L},O,P)\) is implied to be non-expansive.

(ii) We shall then demonstrate the continuous compactness of \({\Psi }({J_2},{K_2},{L_2},{O_2},{P_2})\).

Bounded operators absolute modulus J, K,L,O and P specified in (10)–(11) non-zero positive constants \({\eta _{J}},{\eta _{K}},{\eta _{L}},{\eta _{O}},{\eta _{P}},{\zeta _{J}},{\zeta _{K}},{\zeta _{L}},{\zeta _{O}}~ and ~{\zeta _{P}}\) proving the operator’s compactness by satisfying the following bounded-ness inequalities

\({\Psi }({J_2},{K_2},{L_2},{O_2},{P_2})\).

\(\mathscr {B}\) represents a closed subset of \(\mathfrak {Z}\).

For \(({J},{K},{L},O,P)\in \mathscr {B}\), we find

The same is shown for additional elements. Finding the maximum norm continues \(\Vert \psi ({J_2},{K_2},{L_2},{O_2},{P_2})\Vert\) as,

where a positive constant is denoted by \(\phi\). A uniformly bounded operator, is

We shall now demonstrate that \(t_x<t_y \in [0,\mathbb {T}]\), h is uniformly continuous. We have for \(t_1<t_2 \in [0,\mathbb {T}]\) for this purpose.

Similarly,

As \(t_2\rightarrow t_1\) is independent of \((N,I,\alpha S, M,T)\). This implies that

\(\Rightarrow \psi ({J_2},{K_2},{L_2},{O_2},{P_2}),\) represents an operator that is equi-continuous and complete.

\(\Rightarrow \psi ({J_2},{K_2},{L_2},{O_2},{P_2}),\) it is reasonably concise, according to Arzela’s theorem.

The existence of a unique singular solution is guaranteed by the compactness of the operators \({\Phi }\) and \({\Psi }\), according to the Krasnoselski theorem. \(\square\)

Theorem 4.2

The model solution (3) is regarded as unique if

where \(Q=\max \{\mathscr {W}_{{J}},\mathscr {W}_{{K}},\mathscr {W}_{{L}},\mathscr {W}_{{O}},\mathscr {W}_{{P}}\}.\)

Proof

Establish an operator \(\beth =(\beth _1,\beth _2,\beth _3,\beth _4,\beth _5): \mathfrak {Z}\rightarrow \mathfrak {Z}\) utilizing (20) as:

For \((N,I,\alpha S)\), \((\bar{N},\bar{I},\bar{\alpha S}),{\bar{M}},{\bar{T}}\) \(\in \mathfrak {Z}\), and utilizing (22) we have,

\(\Vert N-\bar{N}\Vert \rightarrow 0\) when \(N\rightarrow \bar{N}\). Hence

with

Using this approach, we find

The model unique fixed-point solution is confirmed using \(\beth\), combining Schauder and Krasnoselski theorems. \(\square\)

Stability analysis

Local stability analysis

Theorem 5.1

When \({R_0} < 1\), the Parkinson disease free equilibrium \({E_\oplus }\) is asymptotically locally stable. There is unstable if \({R_0} > 1\).

Proof

For the system (3) at \({E_\oplus }\), the Jacobian can be expressed as

The following are the resultant eigenvalues when the parameter values from Table (1) are substituted into the Jacobian matrix: \({\lambda _1} = - 0.0402\), \({\lambda _2} = - 0.0150\), \({\lambda _3} = - 0.0150\), \({\lambda _4} = -0.0407\), \({\lambda _5} = -0.0397\). Hence, the point \(E_\oplus\) is locally asymptotically stable. \(\square\)

Global stability analysis

Global stability, in this context, ensures that the system will converge to the endemic equilibrium regardless of initial conditions, reflecting the irreversible progression of Parkinson’s disease once it surpasses a critical threshold. Biologically, this highlights the importance of early intervention to prevent the system from settling into a persistent diseased state.

First derivative of Lyapunov

For the endemic Lyapunov function, \(\{ N, I, \alpha S, M, T\},\) \({}^{FFM}D_{0,t}^{\varpi ,\vartheta }L\) < 0, is the endemic equilibrium \({E^\oplus }\).

Theorem 5.2

Global asymptotic stability is achieved by the model endemic equilibrium points \({E^ \oplus }\) when the reproduction number \(R_0\) > 1.

Proof

The following is a representation of the Lyapunov function:

Differentiating both sides with respect to t.

The following is now an expression for their derivative:

Putting \(N = N - {N^ * }\), \(I = I - {{I}^ * }\), \(\alpha S = \alpha S - {{\alpha S}^ * }\), \(M = M - {{M}^ * }\) and \(T = T - {T^ * }\) leads to.

after some computational

It is achieved that if \(\mathfrak {A}_1 < \mathfrak {A}_2\), this yields \({}^{FFM}D_{0,t}^{\varpi ,\vartheta } L < 0\), however when \(N = {N^*},I = {{I}^*},\alpha S = {{\alpha S}^*},M = {M^*} ~ and ~ T = {T^*}.\)

The proposed model is shown to have the biggest compact invariant set.

Thus, if \({\mathfrak {A} _1} < {\mathfrak {A} _2}\), then the endemic equilibrium points \(E^\oplus\) are asymptotically stable globally within the invariant region. \(\square\)

The analysis confirms that when the basic reproduction number \(R_0<1\), the disease-free equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable, indicating eradication. Conversely, if \(R_0>1\), the endemic equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable, indicating the persistence of the disease.

Chaos control

In this section, we use the linear feedback control strategy to stabilize the system (3) at equilibrium positions. The fractional-order system depicted in its controlled state (3) will be the focus of the following analysis:

where \(E_\oplus\) represents the system equilibrium point and \(\varepsilon _1\), \(\varepsilon _2\), \(\varepsilon _3\), and \(\varepsilon _4\) are control variables. For the system (29), the Jacobian matrix at \(E_\oplus\) is built as

\(\varepsilon _1=1,\varepsilon _2=2,\varepsilon _3=3,\varepsilon _4=4, \varepsilon _5=5\) is the selection. The polynomial roots related to equilibrium point \(E_\oplus\) are determined.

Moreover, \(\lambda _1= -1.0402\), \(\lambda _2= -4.0150\), \(\lambda _3= -5.0150\), \(\lambda _4= -2.0403\) and \(\lambda _5= -3.0400\) are computed as the characteristic roots of Eq. (30). Given that each of the eigenvalues is a negative real number, \(E_\oplus\) is an asymptotically stable equilibrium point. The chaotic behavior of the Proposed model show in Figs. 4, 5 and 6.

Numerical scheme

In this section, we will solve the system (3) numerically using the Newton polynomial.

Simplifying the given system

Fractal-fractional integral with Mittag–Leffler kernel yields:

Reviewing the Newton polynomial

To solve equations (33), the Newton polynomial can be utilized. This provides us

To determine the integrals in the equations (34), perform the following calculations.

As a result, we finally get

Similarly solve for I, \(\alpha S\), T, M.

Where

Remark: The Newton polynomial method is chosen for its superior accuracy in approximating solutions of fractional-order systems with memory effects, especially under the Mittag–Leffler kernel. Its higher-order interpolation capability ensures better convergence and computational efficiency compared to conventional methods when modeling complex neurodegenerative dynamics.

Results of proposed scheme

A mathematical analysis of Parkinson’s disease’s non-linear model has been explained. To observe the sound affects of the parameters used in this Parkinson’s disease model, several of numerical simulations based on the parameter values are carried out to validate the effect of the fractional derivative on the compartments. The Fractal fractional derivative is used to generate the model’s numerical results for different fractional values according to the steady-state point. The graphs of the approximate solutions against different fractional-order \(\varpi\) are provided as in Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16. In Fig. 7 lower fractional orders \(\varpi\) slow the decline of N(t), indicating prolonged neuron survival compared \(\varpi =1\). This show that memory effects preserve neuron functionality for longer, delaying the onset of severe neurodegeneration. Smaller \(\varpi\) values delay the rise and reduce the peak of I(t) in Fig. 8, indicating a slower infection progression. This reflects a moderated infection spread, likely due to the influence of immune defenses or slower neuronal susceptibility to infection. In Fig. 9 when decreasing fractional order then results in a slower buildup and reduced maximum of extracellular \(\alpha\)-synuclein. This indicates reduced aggregation of toxic proteins, potentially limiting their harmful effects on neurons. Smaller fractional order values delay and moderate microglial activation in Fig. 10, resulting in a less aggressive inflammatory response. This suggests that inflammation is better regulated, reducing collateral damage to healthy neurons. In Fig. 11 decreasing fractional order value slows the activation of T cells, leading to a delayed and less intense immune response. This controlled immune activation reduces the risk of chronic inflammation and neurodegeneration. In Fig. 12\(R_0>1\), decreasing fractional order still slows neuron degradation, though the disease progression state accelerates overall decline. Slower degradation reflects improved resilience even in a worsening disease environment. Lower \(\varpi\) delays the peak of infection and reduces its intensity in Fig. 13, even in an active disease state. The slower spread of infection provides a buffer against rapid neurodegeneration. Decreasing fractional order values slow down protein aggregation and reduce toxic buildup in Fig. 14. Slower accumulation of \(\alpha\)-synuclein reduces its neurotoxic effects in disease progression. Microglial activation Fig. 15 is delayed and reduced for smaller \(\varpi\), even with disease progression. A moderated inflammatory response minimizes further neuronal damage. Decrease \(\varpi\) delays and moderates T cell activation in Fig. 16, even under worsening disease dynamics. Controlled immune activation prevents excessive inflammation, reducing overall tissue damage.

Fractional-order models capture real-world phenomena like prolonged inflammatory responses, delayed disease recovery, and memory-dependent dynamics that integer-order models cannot. They are particularly suited to biological systems with feedback loops and time-dependent processes. The fractal-fractional derivative with the Mittag-Leffler kernel effectively models the memory-dependent and prolonged dynamics of Parkinson s disease. Its non-local properties capture the slow accumulation of \(\alpha\)-synuclein and persistent immune activation, offering deeper insights into neurodegenerative processes.

Conclusion

A nonlinear compartmental model was developed in order to have a better understanding of the dynamics of Parkinson’s disease. There are five separate compartments in this model. Additionally, a fractional-order model was developed using fundamental mathematical methods. The well-posedness of the model’s nonlinear ordinary differential equations was confirmed by a thorough investigation. The Banach fixed-point theorem was utilized in the nonlinear functional analysis to ensure the existence and positivity of solutions. Finding the fractional-order Parkinson’s disease model’s equilibria required both a qualitative assessment and a quantitative investigation. Local Stability is explored, to determine the global stability of the fractional order Parkinson s disease model, a Lyapunov function was utilized. The use of PID controllers and chaos control further demonstrates the model’s applicability for exploring therapeutic interventions. Numerical simulations using Newton polynomial schemes validated the model’s behavior across disease-free and endemic states. This framework not only enhances understanding of Parkinson’s disease dynamics but also provides a robust basis for designing personalized control strategies. Future work may involve extending the model to include stochastic effects or spatial heterogeneity for more comprehensive insights.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mehra, S., Sahay, S., & Maji, S. K. a-Synuclein misfolding and aggregation: Implications in Parkinson s disease pathogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Proteins Proteom. 1867(10), 890–908 (2019).

Schwab, A. D. et al. Immunotherapy for Parkinson s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 137, 104760 (2020).

Lee, H. J. et al. Autophagic failure promotes the exocytosis and intercellular transfer of a-synuclein. Exp. Mol. Med. 45(5), e22–e22 (2013).

Overk, C. R. & Masliah, E. Pathogenesis of synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 88(4), 508–516 (2014).

Recasens, A. et al. Lewy body extracts from Parkinson disease brains trigger a-synuclein pathology and neurodegeneration in mice and monkeys. Ann. Neurol. 75(3), 351–362 (2014).

Chu, Y. & Kordower, J. H. The prion hypothesis of Parkinson s disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 15, 1–10 (2015).

Li, J. Y. et al. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat. Med. 14(5), 501–503 (2008).

Hoffmann, A. C. et al. Extracellular aggregated alpha synuclein primarily triggers lysosomal dysfunction in neural cells prevented by trehalose. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 544 (2019).

Desplats, P. et al. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of a-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106(31), 13010–13015 (2009).

Kwon, S., Iba, M., Kim, C. & Masliah, E. Immunotherapies for aging-related neurodegenerative diseases emerging perspectives and new targets. Neurotherapeutics 17(3), 935–954 (2020).

Arcuri, C., Mecca, C., Bianchi, R., Giambanco, I. & Donato, R. The pathophysiological role of microglia in dynamic surveillance, phagocytosis and structural remodeling of the developing CNS. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10, 191 (2017).

Town, T., Nikolic, V. & Tan, J. The microglial’’ activation’’ continuum: from innate to adaptive responses. J. Neuroinflamm. 2, 1–10 (2005).

Vedam-Mai, V. Harnessing the immune system for the treatment of Parkinson s disease. Brain Res. 1758, 147308 (2021).

Schonhoff, A. M., Williams, G. P., Wallen, Z. D., Standaert, D. G. & Harms, A. S. Innate and adaptive immune responses in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Brain Res. 252, 169–216 (2020).

Jurga, A. M., Paleczna, M. & Kuter, K. Z. Overview of general and discriminating markers of differential microglia phenotypes. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 198 (2020).

Bae, E. J. et al. Antibody-aided clearance of extracellular a-synuclein prevents cell-to-cell aggregate transmission. J. Neurosci. 32(39), 13454–13469 (2012).

Chatterjee, D. & Kordower, J. H. Immunotherapy in Parkinson s disease: Current status and future directions. Neurobiol. Dis. 132, 104587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104587 (2019).

Lloret-Villas, A., Varusai, T. M., Juty, N., Laibe, C., Le Novere, N., Hermjakob, H., & Chelliah, V. The impact of mathematical modeling in understanding the mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration: evolving dimensions and future directions. CPT Pharmacometr. Syst. Pharmacol. 6(2), 73-86 (2017).

Sarbaz, Y. & Pourakbari, H. A review of presented mathematical models in Parkinson s disease: black-and gray-box models. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 54, 855–868 (2016).

Puri, I. K. & Li, L. Mathematical modeling for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 5(12), e15176 (2010).

Hao, W. & Friedman, A. Mathematical model on Alzheimer s disease. BMC Syst. Biol. 10, 1–18 (2016).

Kuznetsov, I. A. & Kuznetsov, A. V. What can trigger the onset of Parkinson’s disease A modeling study based on a compartmental model of a-synuclein transport and aggregation in neurons. Math. Biosci. 278, 22–29 (2016).

Kuznetsov, I. A. & Kuznetsov, A. V. Mathematical models of a-synuclein transport in axons. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 19(5), 515–526 (2016).

Sneppen, K., Lizana, L., Jensen, M. H., Pigolotti, S. & Otzen, D. Modeling proteasome dynamics in Parkinson’s disease. Phys. Biol. 6(3), 036005 (2009).

Ahmad, A., Farman, M., Sultan, M., Ahmad, H. & Askar, S. Analysis of Hybrid NAR-RBFs Networks for complex non-linear Covid-19 model with fractional operators. BMC Infect. Dis. 24(1), 1051 (2024).

Farman, M., Hasan, A., Xu, C., Nisar, K. S. & Hincal, E. Computational techniques to monitoring fractional order type-1 diabetes mellitus model for feedback design of artificial pancreas. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 257, 108420 (2024).

Nisar, K. S., Farman, M., Hincal, E., Hasan, A. & Abbas, P. Chlamydia infection with vaccination asymptotic for qualitative and chaotic analysis using the generalized fractal fractional operator. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 25938 (2024).

Farman, M., Shehzad, A., Nisar, K. S., Hincal, E. & Akgul, A. A mathematical fractal-fractional model to control tuberculosis prevalence with sensitivity, stability, and simulation under feasible circumstances. Comput. Biol. Med. 178, 108756 (2024).

Xu, C., Farman, M., Pang, Y., Liu, Z., Liao, M., Yao, L., et al. Mathematical analysis and dynamical transmission of (SEIrIsR) model with different infection stages by using fractional operator. Int. J. Biomath. (2024).

Nisar, K. S., Farman, M., Jamil, K., Akgul, A. & Jamil, S. Computational and stability analysis of Ebola virus epidemic model with piecewise hybrid fractional operator. PLoS One 19(4), e0298620 (2024).

Nisar, K. S., Farman, M., Zehra, A., & Hincal, E. Numerical and analytical study of fractional order tumor model through modeling with treatment of chemotherapy. Int. J. Model. Simul. 1–14 (2024).

Zarin, R., Humphries, U. W. & Saleewong, T. Advanced mathematical modeling of hepatitis B transmission dynamics with and without diffusion effect using real data from Thailand. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 139(5), 385 (2024).

Raezah, A. A., Zarin, R. & Raizah, Z. Numerical approach for solving a fractional-order norovirus epidemic model with vaccination and asymptomatic carriers. Symmetry 15(6), 1208 (2023).

Zarin, R., Raouf, A., khan, A. & Humphries, U. W. Modeling hepatitis B infection dynamics with a novel mathematical model incorporating convex incidence rate and real data. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138(11), 1056 (2023).

Yunus, A. O. & Olayiwola, M. O. Dynamics of Ebola virus transmission with vaccination control using Caputo-Fabrizio Fractional-order derivative analysis. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 11(3), 1–18 (2025).

Yunus, A. O. & Olayiwola, M. O. The analysis of a co-dynamic ebola and malaria transmission model using the laplace adomian decomposition method with caputo fractional-order. Tanzania J. Sci. 50(2), 224–243 (2024).

Yunus, A. O. & Olayiwola, M. O. Epidemiological analysis of Lassa fever control using novel mathematical modeling and a dual-dosage vaccination approach. BMC. Res. Notes 18(1), 199 (2025).

Yunus, A. O., Olayiwola, M. O., Omoloye, M. A. & Oladapo, A. O. A fractional order model of lassa disease using the Laplace-adomian decomposition method. Healthc. Anal. 3, 100167 (2023).

Yunus, A. O., & Olayiwola, M. O. Mathematical modeling of malaria epidemic dynamics with enlightenment and therapy intervention using the Laplace-Adomian decomposition method and Caputo fractional order. Franklin Open 100147 (2024).

Yunus, A. O., & Olayiwola, M. O. Simulation of a novel approach in measles disease dynamics models to predict the impact of vaccinations on eradication and control. Vacunas 100385 (2025).

Yunus, A. O., Olayiwola, M. O. & Ajileye, A. M. A fractional mathematical model for controlling and understanding transmission dynamics in computer virus management systems. Jambura J. Biomath. JJBM 5(2), 116–131 (2024).

Olayiwola, M. O., Yunus, A. O., Ismaila, A., Alaje, & Adedeji, J. A. Modeling within-host Chikungunya virus dynamics with the immune system using semi-analytical approaches. BMC. Res. Notes 18(1), 201 (2025).

Farman, M., Xu, C., Shehzad, A. & Akgul, A. Modeling and dynamics of measles via fractional differential operator of singular and non-singular kernels. Math. Comput. Simul. 221, 461–488 (2024).

Zarin, R. A robust study of dual variants of SARS-CoV-2 using a reaction-diffusion mathematical model with real data from the USA. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138(11), 1–23 (2023).

Raizah, Z. & Zarin, R. Advancing COVID-19 understanding: Simulating omicron variant spread using fractional-order models and haar wavelet collocation. Mathematics 11(8), 1925 (2023).

Zarin, R. & Haider, N. Numerical solution of COVID-19 pandemic model via finite difference and meshless techniques. Eng. Anal. Boundary Elem. 147, 76–89 (2023).

Olayiwola, M. O. & Yunus, A. O. Non-integer time fractional-order mathematical model of the COVID-19 pandemic impacts on the societal and economic aspects of Nigeria. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 10(2), 90 (2024).

Han, M., Xi, J., Xu, S. & Yin, F. L. Prediction of chaotic time series based on the recurrent predictor neural network. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 52(12), 3409–3416 (2004).

Sun, Y., Zhang, L. & Yao, M. Chaotic time series prediction of nonlinear systems based on various neural network models. Chaos Solitons Fractals 175, 113971 (2023).

A. Atangana, Fractal-fractional differentiation and integration: Connecting fractal calculus and fractional calculus to predict complex system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 102, 396–406 (2017).

Al-Tuwairqi, S. M. & Badrah, A. A. Modeling the dynamics of innate and adaptive immune response to Parkinson s disease with immunotherapy. AIMS Math. 8(1), 1800–1832 (2023).

Atangana, A. Mathematical model of survival of fractional calculus, critics and their impact: How singular is our world?. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021(1), 403 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F., A.T., K.J., K.S.N., A.S., M.B. and M.H. wrote the main manuscript text and M.F., A.T., K.J., K.S.N. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farman, M., Talib, A., Jamil, K. et al. Monitoring and investigation to control the brain network disease under immunotherapy by using fractional operator. Sci Rep 15, 30161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15307-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15307-y