Abstract

Carbohydrates are vital for honey bee energy, fitness, and survival, influencing colony dynamics and resilience. This study examined the effects of various carbohydrate sources on honeybee longevity, hypopharyngeal gland size, gene expression, and gut microbiome composition. Newly emerged bees were fed white sugar, brown sugar, corn syrup (CS), maltose, acacia honey, chestnut honey, and oligosaccharide ad libitum. Bees fed CS showed the highest longevity, followed by acacia honey and white sugar, while oligosaccharide-fed bees had the lowest longevity. CS-fed bees also exhibited larger hypopharyngeal glands, correlating with improved survival. Gene expression analysis revealed upregulation of Ilp2 and Vg and downregulation of Ilp1 in 14-day-old bees fed with CS which may be linked to enhanced longevity. Gut microbiome analysis showed the higher composition of Frischella in honey fed treatment groups and Bartonella in processed carbohydrates treated groups, potentially compensating for dietary amino acid deficiencies. However, the absence of core symbionts like Snodgrassella in CS-fed bees may weaken immunity and heighten disease susceptibility. These findings suggest starch-derived corn syrup as a promising carbohydrate source under laboratory conditions, however, long-term colony-level studies are essential to fully understand its benefits and potential risks. This research provides valuable insights for honey bee management and conservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

European honey bee (Apis mellifera) is known for its crucial role in pollinating various crops, thereby underlining its paramount importance in agricultural ecosystem1. Beyond their agricultural relevance, honey bees are decisive for preserving the biodiversity of plant species and supporting natural habitats. Nevertheless, over the past three decades, honey bee populations have experienced a significant decline with particularly high losses over the winter2,3 which Several factors are attributed to this, including presence of parasites, exposure to agrochemicals, and poor nutrition4,5. Nutrition plays a fundamental role in determining the health of honey bees and inadequate nutrition makes bees more susceptible to pesticides and compromises their immune systems, making them vulnerable to diseases.

The typical honey bee diet comprises flower nectar, which is the main source of carbohydrates to colony but also may contain a small amount of amino acids and lipids6, and pollen, either consumed fresh or stored as bee bread, providing protein and a range of lipids7. However, during certain periods of the year, natural resources can become scarce and may not align with the colony’s requirements. In addition, in specific regions with long rainy seasons, foraging is not feasible for honey bees leading to the scarcity of nutrients which can impact brood rearing, honey production, and the overall growth and development of the colony8. Artificial carbohydrate feeding can not only help maintain colony populations but also bolster their resilience in the face of environmental stressors and fluctuations in natural forage availability.

Artificial carbohydrate sources, often in the form of sugar syrup or fondant, step in as a crucial lifeline for these industrious insects. Numerous types of carbohydrates such as sucrose syrup, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), and invert sugar are being commonly used as an artificial feed because these carbohydrate sources are inexpensive, easy to obtain, and readily eaten by the bees8. Previous research has explored the impact of supplementing artificial carbohydrates on both colony and individual bee health, often finding no significant differences among the types of feeds. For instance, while sucrose syrup improved the survival of caged honey bees9, studies on colony-level experiments did not show notable variations in weight gain, honey production, cluster size, worker weight, or overwintering survival across different carbohydrate supplements9,10,11. However, given the current challenges of high winter and summer losses in honey bee colonies3,11, there is an ongoing need to research the most effective artificial supplementary diets to enhance honey bee survival.

Simply extending lifespan alone may not be the sole indicator of success. It may prove more effective when, in addition to increased longevity, other aspects of honey bee physiology and tissue health are improved. The development of hypopharyngeal glands (HPGs) can be negatively impacted by various biotic and abiotic stressors, including factors like honey bee races, food availability, seasonal variations, and exposure to pesticides12. The size of the hypopharyngeal glands (HPGs) has long served as a dependable indicator of the nutritional status of honey bees13. Numerous studies have explored the positive correlation between a supplementary diet, various types of pollen, and the size of the hypopharyngeal glands. The acini size can be increased by feeding honey bees by enriching protein source and consequently higher production of royal jelly. However, there is currently no evidence to support the effectiveness of specific carbohydrate types in improving these glands.

On the other hand, a meta-analysis examining the gut bacteria composition in other insect species suggests that the dietary choices of insects may have an influence on their bacterial community structure14,15. These gut bacteria are typically symbiotic residents, playing crucial roles in bee nutrition, digestion, reproduction, and defense against toxins and pathogens15,16. Metatranscriptome sequencing has revealed that bacteria play pivotal roles in carbohydrate substrate metabolism. Certain bacteria within this ecosystem act as primary sucrose-feeders, breaking down sugars into monosaccharides, which are subsequently metabolized into acid metabolites like acetate and lactate. These acid metabolites aid in the decomposition of potentially toxic sugars. Consequently, the gut bacteria contribute to the array of enzymes necessary for effective carbohydrate digestion15.

This study aims to investigate the impact of various carbohydrate sources on the lifespan, and other physiological factors of caged honey bees. Honey bees were treated with different types of carbohydrates including white sugar (WS), brown sugar (BS), maltose (MA), corn syrup (CS) (derived from corn starch), acacia honey (AH), chestnut honey (CH), and oligosaccharides (OS) (Table 1), and the effect of different diet on their key biological and physiological parameters, such as lifespan, feed intake, the microbial composition of the digestive system, the size of hypopharyngeal glands, and the expression of specific genes related to nutrition including Vitellogenin (Vg), insulin-like peptide (Ilp 1,2) were evaluated.

Results

Effect of different types of carbohydrates on the lifespan of caged honey bees

The survival of honey bees from different treatment groups, i.e., those fed with distinct carbohydrate source was depicted in Fig. 1. Honey bees in the group fed only water experienced complete mortality within four days. The results revealed that honey bees fed with CS exhibited significantly higher longevity, compared to the other groups. The honey bees fed with CS displayed the longest longevity, represented by median lethal time (LT50 = 26.5 days), followed by those fed with Acacia honey (LT50 = 22.7 days) and white sugar (LT50 = 19.12 days). Conversely, the lowest longevity was observed in the honey bees fed with oligosaccharide with only LT50 = 3.67 days (Fig. 1, Table S2). Notably, while comparing two honey bee groups fed with different types of honey, the lifespan of honey bees fed with Acacia honey was significantly greater than that of the group received chestnut honey. Furthermore, the group of workers fed with white sugar showed the significantly higher survival rate compare to the group fed with brown sugar. (p < 0.05 (Fig. 1, Table S2).

Food intake and energy level

Analysis of food consumption demonstrated that honey bees treated with high concentrated carbohydrates (corn syrup, acacia, and chestnut honey) consumed significantly less carbohydrate solution and significantly more water (p < 0.05) (Fig. S1). However, no differences were observed in the total amount of sugar consumption and, consequently, energy levels gained between treated groups (Table 1) (Fig. S1).

Measuring HPG acinus size

The size of HPG of honey bees fed with different diet was measured and the results indicated that except in the AH group, the size of acini in 7–day-old workers was significantly larger than those in 14-days-old workers (P < 0.05) (Table S3). Throughout both sampling dates, the smallest acini size was consistently observed in the group fed with white sugar. In 7-day-old bees, workers fed with CS displayed the largest acini size, whereas in 14-day-old bees, CS and acacia honey exhibited the largest acini sizes compared to other treatments. These results underscore the impact of food quality on the development of honey bee acini (Fig. 2).

Gene expression analysis

Significant variations were observed in the expression levels of key genes related to honey bee nutrition among honey bee workers across different age groups and dietary treatments, as illustrated in Fig. 3. in the abdomen, Ilp1 did not differ among treatments on day 7. However, the overall expression pattern of ilp1 indicated an age-related increase, with most groups showing elevated expression in 14-day-old bees and a further, though less pronounced, increase by day 21, except in bees fed corn syrup (CS) and maltose, which deviated from this trend. In the head, the primary site of Ilp expression, Ilp1 levels were highest during the first week, particularly in bees fed artificial honey (AH), while bees fed CS exhibited significantly lower expression. Notably, Ilp1 expression in the head declined significantly in 14- and 21-day-old bees across all treatment groups. The Ilp2 expression in the head closely mirrored that of Ilp1, indicating a general decline over developmental time, except in the CS-fed group. The highest Ilp2 expression was observed in 7-day-old bees, with the AH group displaying the greatest expression, followed by the WS and CH groups. While the CS-fed group showed moderate expression at day 7, a significant increase was detected in 14-day-old bees. By day 21, Ilp2 expression declined across all treatment groups. In contrast, Ilp2 expression in the abdomen tended to peak in 14-day-old bees, followed by a decline at day 21. Among the dietary treatments, bees fed with CS exhibited significantly higher abdominal Ilp2 expression on day 14 compared to the other groups. Vitellogenin (Vg) expression in the abdomen, the main site for Vg expression sharply increased in 14-day-old bees relative to day 7, then declined by day 21 across all treatments. In the head, however, Vg expression showed no consistent trend.

Relative gene expression of Insulin like peptide1 (Ilp1), insulin like peptide2 (Ilp2), and Vitellogenin (Vg) in head and abdomen of honey bee fed with different type of carbohydrates in different age (7, 14, 21 days old) relative expression Ilp1 (A), Ilp2 (B), Vg (c) in head and in relative expression Ilp1 (D), Iilp2 (E), and Vg (F) in abdomen (p < 0.05). Acacia honey (AH), brown sugar (BS), chestnut honey (CH), corn syrup (CS), maltose (MA), white sugar (WS).

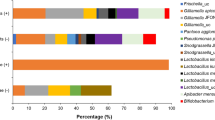

Gut Microbiome analysis

In all treatments, three primary Phylotypes, namely, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria, were consistently observed (Fig. 4A, B, C). Proteobacteria was found predominant, representing 80–90% of the overall gut microbiota, with Firmicutes following at 6–18% of the total gut microbes (Table S5). Among Proteobacteria, Bartonella emerged as the most dominant taxa across all treatment groups, except for honey bees fed with chestnut honey (Fig. 4B). Bartonella was notably higher in worker bees that received CS, constituting over 80% of the total gut bacteria. Conversely, the CH group exhibited the lowest Bartonella, accounting for only 6% of bacterial composition. Friscella, Snodgrassella, Gilliamella and Commensalibacter are the other Proteobacteria, however, three of these core bacteria (Friscella, Snodgrassella, and Commensalibacter) were absent in honey bees fed with CS, resulting in the lowest bacterial taxa richness and diversity in the gut of workers from this group (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, among Firmicutes, abundance of Lactobacillus was significantly higher in the group fed with CH, comprising 18% of the bacterial composition. Interestingly the lowest population of Lactobacillus, were observed in WS and AH group. Also information about sequence quality control analysis of gut microbiome experiment provided in table S6.

(A) The euclidean distance–based dendrogram summarizes the differentiation among gut microbiome composition in different treatments. (B) Bar charts showing the relative abundance of the dominant gut bacteria communities in 14 days old honey bees; Taxa accounting for < 1% of reads are grouped as “Other taxa”. (C) Evolutionary tree by using UPGMA methods. Bar chart layer indicates the relative abundance of ASVs in different treatment groups and different colors in the outer layer indicates the phylum level identification of ASVs (p < 0.05). (D) Correspondence analysis (CA) representing the bacterial taxa and their abundances inside the gut from different treatments. (E) Shannon diversity index of gut bacteria in honey bees fed with different type of carbohydrates. Acacia honey (AH), brown sugar (BS), chestnut honey (CH), corn syrup (CS), maltose (ML), newly emerged (New), white sugar (WS).

The PCA plot illustrates the gut microbiome variation in honey bees fed with different carbohydrates, with the first two principal components explaining 35.45% of the total variability. Chestnut honey (CH) samples are distinctly separated along Dim 1, while the other groups of bees cluster around the center or the negative side of Dim 1, suggesting a unique influence of CH on the honey bee gut microbiome (Fig. 4D). The distant relationship of the gut microbiome composition of CH-fed group is also demonstrated by dendrogram analysis (Fig. 4A).

Discussion

Carbohydrates serve as the primary energy source for honey bees, ensuring their vitality and sustenance. Especially during the dearth season when foraging becomes challenging, bees rely heavily on either stored honey or alternative forms of carbohydrates provided by beekeepers17,18.

The CS group exhibited the highest survival rate among the treatment groups, whereas the oligosaccharide group showed the lowest survival. Previous research aligns with our findings, showing that honey bees receiving diets high in oligosaccharides or polysaccharides exhibit lower survival rates due to the difficulty in digesting these complex carbohydrates19. Our initial expectation was that honey, being rich in nutrients, would serve as a superior nutritional source, supporting higher survival rates or longevity. However, contrary to our expectations, this study indicated that CS performed better in supporting honey bee survival and HPG development compared to the two tested honey types, acacia and chestnut honey. Further research including a broader range of honey types is needed to draw more general conclusions. It should also be noted that the carbohydrate treatments differed in sugar concentration, as sugar syrup was diluted to 50% (w/v), whereas honey and corn syrup were provided in their natural, undiluted form. Despite these differences, no significant variation was observed in total sugar or energy intake across treatments, as bees consuming higher-concentration feeds ingested less solution but drank more water. This behavioral adjustment likely allowed them to regulate their energy intake, but the variation in concentration may still have influenced feeding behavior or physiological outcomes and should be considered when interpreting results.

Honey bees metabolize monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose, and disaccharides like sucrose, trehalose, and maltose. The CS used in this experiment consisted of a mixture of a limited amount of glucose and sucrose, a very high proportion of maltose (57.1%) and polysaccharide (Table S1). An earlier study19, which examined the effects of different carbohydrates on honey bee lifespan, demonstrated that bees fed with honey or maltose exhibited longer lifespans compared to those fed with other carbohydrate types. The superior performing of CS compared to maltose alone may be attributed to its balanced carbohydrate composition. The limited amount of glucose in CS likely facilitates improved digestion, acting as a primer for maltose digestion. Additionally, the presence of sufficient amounts of glucose, sucrose, and maltose allows adequate time for the slower digestion of polysaccharide, which requires a longer period to break down. This staged digestion process supports the continuous release and absorption of carbohydrates, ensuring a steady supply of energy to the bees20. Barker and Lehner9 reported that worker bees fed sucrose syrup exhibited higher survival rates compared to those provided with mixed-floral honey or high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). Similarly, Sammataro and Weiss21 observed improved colony performance in colonies fed with sucrose syrup over those fed HFCS. In contrast to these findings, in our study, CS was more effective than other treatments in prolonging honey bee lifespan. A key distinction in our study is that the CS used was derived from corn starch and contained high levels of maltose and polysaccharide, setting it apart from conventional HFCS. In this study, the group of honey bees fed with acacia honey demonstrated a higher longevity compared to the group consuming chestnut honey which may be attributed to differences in their composition and effects on bee physiology. AH is characterized by a higher fructose-to-glucose ratio and greater total mono and disaccharide content (Table S1), making it a more readily digestible energy source for honey bees. This readily available carbohydrate profile likely supports bee metabolism and contributes to enhanced survival. In contrast, chestnut honey is known for its richness in minerals and complex phenolic compounds22. Studies have shown that chestnut honey contains approximately 1.83 mg/g of phenolic compounds, which is significantly higher than the 0.51–0.63 mg/g found in acacia honey. It also exhibits greater antioxidant activity, with 1.82 mg of vitamin C equivalents per gram, compared to 0.33–0.39 mg/g in acacia honey23. While these antioxidant-rich and phenolic compounds are considered beneficial to human health, they may pose metabolic challenges for bees. The complex nature of chestnut honey’s composition might be less readily metabolized and could potentially induce oxidative stress if antioxidants act in excess as pro-oxidants22.

While numerous studies have investigated the efficacy of various types of protein sources on the size of HPGs24,25,26,27 as an indicator of the protein intake from their diet, there is limited research examining the effect of carbohydrate sources on these glands. In our investigation, we observed that honey bees fed CS exhibited the largest HPG size among 7 and 14 day old bees. Ikeya et al.28 found that increased food intake or elevated nutrient stores can stimulate the synthesis of insulin-like peptides (ILPs) in insects, thereby suppressing glucagon synthesis.

In carbohydrate metabolism, the interplay between gluconeogenesis and glycolysis is crucial. Honey, through these pathways, can product amino acids such as Serine, Alanine, Aspartate, and Glutamine, potentially contributing to protein sources29. Consequently, these amino acids may play a role in modulating the size of HPGs. CS, characterized by the combination of mono, di and oligo/polysaccharides, offers a sustained energy source due to the prolonged digestion time of long-chain carbohydrate molecules. This steady energy release may lead to reduced energy consumption and protein production, influencing both honey bee longevity and HPG size. Overall, our findings suggest a complex interplay between carbohydrate sources, metabolic pathways, hormonal regulation, and HPG size in honey bees, highlighting the multifaceted nature of their nutritional physiology and its implications for colony health and performance. However, it is important to acknowledge that HPG development is heavily influenced by protein intake. In this study, no protein-rich diet (such as pollen or pollen substitute) was provided, as the experiment was intentionally designed to isolate the effects of carbohydrate sources. While this allowed for a clearer assessment of carbohydrate-specific effects, it limits the interpretation of HPG-related outcomes. The observed differences in HPG size likely reflect energy-driven physiological responses rather than direct protein-induced development. Future studies should incorporate protein supplementation to better understand how carbohydrates interact with dietary protein in shaping HPG development and overall bee physiology.

The complex interplay between feed compositions and gene expression in honey bees highlights a multifaceted relationship involving nutritional quality, physiological pathways, and colony health. The vital biomarker, Vg, not only signals developmental rate and longevity but also reflects nutritional sufficiency and resilience against stress and diseases30. This is tightly connected to the insulin/insulin-like signaling (IIS) pathway, particularly through the action of Ilp1 and Ilp231, which regulate nutrient sensing, metabolism, aging and behavioral transitions32,33. Our results show that bees fed CS had the longest lifespan, followed by those fed AH, as indicated by survival analysis. Notably, Ilp1 expression in head was relatively low in the CS-fed group, which aligns with earlier findings that associate reduced Ilp1 levels with suppressed IIS pathway activity, favoring somatic maintenance, delayed senescence, and lifespan extension34. Ilp1, acting as an agonist of the insulin receptor (InR)32, activates nutrient mobilization and metabolic pathways35, so its suppression may reflect a physiological shift toward energy conservation and longevity. Interestingly, Ilp2 expression in head increased in the CS group at day 14, suggesting a regulatory mechanism that further dampens IIS signaling by acting as an antagonist32 or competitive inhibitor of Ilp1 at InR. This balance, low Ilp1 and high Ilp2, may represent an optimal hormonal state for supporting homeostasis and survival, especially in the absence of complex nutrients.

In contrast, AH-fed bees showed elevated expression of both Ilp1 and Ilp2, along with significantly larger hypopharyngeal glands (HPGs) at day 7. The large gland size suggests enhanced nutritional intake and glandular activity36, likely driven by the diverse nutrient profile of AH. While high Ilp1 typically implies increased IIS activity, often associated with a shorter lifespan phenotype31, the co-expression of Ilp2 may serve to fine-tune the metabolic response, preventing overstimulation of the pathway. Additionally, honey’s antioxidants, amino acids, and phytochemicals could contribute to cellular protection and longevity through pathways downstream of IIS31. Although chestnut honey generally contains a higher total amount of amino acids, acacia honey has been reported to contain higher levels of essential amino acids37. These essential amino acids may play a more critical role in modulating metabolic and developmental pathways, contributing to the enhanced expression of insulin-like peptides and greater HPG development observed in AH-fed bees. The discrepancy in longevity between the AH and CH groups, despite similar Ilp expression levels, underscores that honey type and quality have differential effects on downstream physiological pathways. These differences may influence the titer of JH, and Vg, and may ultimately affect aging trajectories and task-related behavior in worker bees. Together, our findings suggest that the relationship between diet, Ilp expression, and longevity is not linear, but instead depends on a complex interaction of energy content, nutrient diversity, and endocrine regulation.

Honey bees host a fundamental gut microbiota consisting of five primary bacterial lineages: Gilliamella, Snodgrassella, Lactobacillus Firm 4, Lactobacillus Firm 5, and Bifidobacterium39,40 collectively constituting 95% of the total community. Additionally, there are less abundant but ubiquitous bacteria, including Frischella, Commensalibacter, and Bartonella41.

In our research, we noted a shift in the gut microbiota of honey bees when they were exclusively fed a carbohydrate-based diet. Specifically, less dominant bacteria like Frischella and Bartonella became more prevalent. This discovery is in line with findings by Taylor et al.15, who showed that diets rich in sucrose led to increased relative abundances of certain less dominant core bacteria, including Bartonella, Acetobacteraceae, and Lactobacillus kunkeei.

The research was carried out under controlled laboratory conditions, where the adult honey bees were supplied solely with a carbohydrate source. While carbohydrates can be converted into amino acids, this process does not yield essential amino acids, which are vital for the bees’ nutrition29. Essential amino acids must be obtained from their diet, as they cannot be synthesized internally by the bees. Given the need for these essential nutrients, it is hypothesized that the higher levels of Bartonella observed in the honey bee gut may play a significant role. These bacteria are capable of contributing nitrogen, which could potentially aid in the synthesis of amino acids, thereby compensating for the lack of essential amino acids in the bees’ diet. However, the specific biochemical pathways through which Bartonella might facilitate this contribution to amino acid synthesis have yet to be thoroughly investigated. Since the bees in our study were confined to an incubator without the opportunity to forage, their situation may resemble that of winter bees. Kešnerová et al.42 found differences in the bacterial composition of the gut between winter and summer honey bees. They observed the dominance of Bartonella during winter, accompanied by a conspicuous decrease in core bacteria. This shift was likely due to Bartonella’s enhanced fitness under reduced pollen diets, as it can utilize alternative energy sources such as lactate, acetate, and ethanol. Comparative genomics suggested that Bartonella might produce essential amino acids, serving as a crucial supplement for honey bees facing protein-deficient diets. Moreover, Bartonella was found to generate pyruvate, an important energy source utilized by both bacteria and the host. Their study indicates a potential role for Bartonella in providing essential amino acids to honey bees, potentially contributing to their health and protein synthesis for brood maintenance during winter. Our research highlights the high percentage of Bartonella in the gut microbiota of honey bees fed with different types of carbohydrates (while there was no pollen source) and suggests that this bacterium may offer substantial benefits by providing abundant energy sources and essential amino acids. This finding can also help us to understand the bigger size of acini in the hypopharingeal gland of honey bee fed with CS than in other treatments. However, it is important to note that this relationship was not directly tested in our study. While Bartonella and other microbiota members have been associated with amino acid metabolism and nutritional support in previous literature, our findings remain observational. As such, the shifts in microbial composition observed across diets should be interpreted descriptively. Further functional studies are needed to confirm whether these microbiota changes have beneficial, neutral, or adverse effects on honey bee health, physiology, or gland development.

The absence of Snodgrassella and Frischella in bees fed with CS suggests a significant alteration in the gut microbiome composition. These bacteria are typically associated with core honey bee microbiomes and play roles in gut health, immune function, and pathogen resistance43,44. Their absence might indicate that CS lacks certain nutrients or bioactive compounds that support their growth or that CS creates a gut environment less conducive to these bacteria. Conversely, the high abundance of Gilliamella and Lactobacillus in the CS-fed group highlights their adaptability to this carbohydrate source. These bacteria are known for their roles in metabolizing sugars and complex carbohydrates45, suggesting that CS provides substrates conducive to their growth. The better performance of bees fed with CS could be attributed to its high energy content and slower digestibility, providing a sustained carbohydrate supply. This suggests that despite microbiome shifts, bees can thrive on CS, at least under the conditions of this study. While these findings suggest CS can support bee longevity and metabolic activity in a controlled setting, its impact on the gut microbiome raises questions about potential long-term trade-offs, including impacts on immune function and resilience to environmental stressors or pathogens. It is important to acknowledge that this study was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions using individual bees. Although this allowed us to isolate the direct effects of carbohydrate sources on physiology and microbiome composition, it limits the ecological relevance of the findings. Colony-level studies are crucial for assessing broader outcomes such as foraging behavior, social dynamics, and overall colony health. Therefore, further field-based and colony-scale research is essential to evaluate whether the observed benefits and microbiome alterations translate into improved colony performance under natural conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our research sheds light on the intricate dynamics of honey bee nutrition, gut microbiota composition, and gene expression in response to different carbohydrate sources. We observed shifts in gut microbiota dominance, with notable increases in Frischella and Bartonella, which may be influenced by the unique metabolic properties and nutrient profile of each carbohydrates source. Gene expression pattern of insulin-like peptides and Vitellogenin further underscore the complex nutritional signaling pathways that contribute to honey bee longevity and health. While corn syrup emerged as a potentially efficient carbohydrate source in terms of energy supply and bee performance under laboratory conditions, the associated reduction in microbial diversity and the absence of key core gut bacteria suggest potential trade-offs. These findings emphasize the importance of evaluating both nutritional efficacy and microbiome integrity when selecting dietary supplements for bees. Ultimately, this research emphasizes the need to go beyond calorie content and consider the broader physiological and microbial implications of different carbohydrate sources. However, as this study was conducted under laboratory conditions and only included two honey types, further field-based and colony-level research is necessary to validate these findings and ensure that nutritional strategies contribute positively to honey bee health, productivity, and resilience in real-world environments.

Material and method

Assessing the lifespan of honey bees

This trial utilized healthy colonies of Apis mellifera derived from sister queens, located within the experimental apiary of Gyeongkuk National University in South Korea, to minimize the influence of genetic variability. Frames containing brood close to emergence were carefully chosen from the colony. Subsequently, these frames were incubated at a controlled environment of 33 °C and 60% relative humidity (RH) for a duration of 24 h and the newly emerged workers, were collected for participation in the experiments. 25 individuals were housed in cages measuring 110 × 90 × 80 mm, featuring a fine mesh top for ventilation. This experiment was conducted in five separate replications, with each cage equipped with two feeding holes on the top for the placement of two feeders for water and carbohydrate solution (Table S1). WS, BS, MA were used by making solution in 1:1 ratio, however AH, CH, OS, and CS were used directly without dilution. As white sugar (WS) is commonly used as a standard carbohydrate source in honey bee management practices, we included it as a positive control in our experiment. The negative control received only water as a food source. Honey bees maintained in incubator throughout the experiment under 30 °C with relative humidity of 60%. Daily observations were made to record bee mortality and consumption rates. Furthermore, three additional replications were incorporated into the experiment. On Days 7 and 14, ten individuals from the extra replications of each treatment group were chosen and preserved at -80 °C for subsequent analysis of their physiological characteristics and gut microbiome.

Measuring hypopharyngeal gland acinus size

The dissection and measurement of hypopharyngeal glands (HPGs) adhered to established protocols outlined by Corby-Harris and Snyder36. Worker bee heads were meticulously separated and carefully placed into individual microcentrifuge capsules, each appropriately labeled. Sterile dissection tools were utilized throughout the procedure. Following this, the HPGs were dissected and imaged using an Olympus SZX10 microscope (Olympus IE, Waltham, MA) in conjunction with an Olympus SC50 microscope camera (Olympus IE, Waltham, MA). To enhance measurement precision, five bees were selected per feeding group, with measurements recorded for ten acini per bee. Subsequently, the average acinus size for each bee within the respective groups was calculated based on a total of 50 acini from the five bees.

RNA extraction, real-time PCR and gene expression analysis

To study the effect of different carbohydrates on the gene expression profile of worker bees, total RNA was extracted from the head and abdomen of pooled five individuals from each replication at 7, 14, and 21 days’ post treatment by using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Immediately after extraction, RNA quantity and purity was evaluated using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop FC-2100, Life Real, China). Using 1 µg of extracted RNA for each treatment, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized BioFACT Reverse Transcription Kit. The synthesized cDNAs were adjusted to 50 µL with sterile water and stored at − 80 °C prior to further for the analysis, Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was conducted by preparing each reaction with a cDNA sample (100 ng) for each treatment serving as a template, along with 10 pM of gene-specific primers (Table S4), SYBR green master mix (BioFACT) and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL. For the first PCR cycle, the reaction mixture was initially denatured at 95 °C for 15 min (1 cycle), followed 30 s at 95 °C for denaturing, 30 s for annealing at 52 °C, and was extend at 72 °C for a total of 40 cycles. Fluorescence was measured at the end of the extension step. A dissociation step (95 °C for 15s, 52 °C for 60s, 95 °C for 15s) was conducted to validate the amplification of a single product in each PCR reaction. Actin served as the reference gene, known for its stable expression across honey bee tissues and commonly use in honey bee research. To obtain the relative quantities of Vg, Ilp1 and Ilp2 genes, threshold cycle (ct) values were used. Data were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔct method (2^(-ΔΔct) = 2^-(Δct treatment-Δct reference))46. In the negative control group, the absence of cDNA template was ensured. The reactions were replicated three times for accuracy. Mean values were compared using one-way analysis of variance (p < 0.05) (Table S4).

Gut microbiome analysis

DNA extraction and sequencing

To study gut microbiome analysis, gut from five samples of each treatment group were dissected and pulled together in a 1.5 mL sterile microcentrifuge tube and DNA was extracted from pooled sample using the QIAGEN DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each DNA sample, the concentration of nucleic acid was evaluated by a Life Real spectrophotometer (Bioer Technology Co., Ltd., Zhejiang, China). Extracted DNA samples were kept at -20 °C prior to library preparation. Two step PCR were used for library preparation and the V3–V4 region of 16 S rRNA was amplified using the primers 341 F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) and sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea). The sequences were submitted to NCBI through the project number PRJNA1114793.

Sequence analysis

The initial assessment of the quality of raw paired-end reads was performed using FastQC (Babraham Bioinformatics, Cambridge, UK). Subsequently, the raw sequences were imported into Qiime247 for analysis using the DADA2 algorithm. This involved trimming the length of forward reads to 270 bp and reverse reads to 220 bp to ensure high-quality reads with a Phred quality score of at least 20. The analysis also included the assembly of forward and reverse reads, as well as chimera detection. The Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) were classified against the SILVA v132 database by default to assign taxonomy. Sequences initially classified as Rhizobiaceae in SILVA were further validated using the NCBI BLASTn tool due to known limitations in the SILVA database, which currently lacks the updated family Bartonellaceae. BLAST results confirmed these sequences to be Bartonella, and the taxonomy was updated accordingly in the final analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.1.0 and SPSS software (version 16.0, SPSS, Chicago, United States). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to determine the effect of different carbohydrates on the lifespan of honey bees. Statistical significance in the time distributions among groups was assessed using the log-rank test via the “survival” package in R. The difference between the size of HPG in different treatment groups was analyzed with One-way ANOVA. One-way analysis of variance was also applied to compare the mean values of the expression of examined genes (p < 0.05). The Shannon diversity index (H’) of the gut samples from different carbohydrate groups was calculated by computing read count values in Excel and the differences between the mean values were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. The difference in biodiversity indices between the bees treated with different types of carbohydrates was measured by one-way ANOVA in SPSS 16.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). We conducted correspondence analysis (CA) to visualize the relationships between bacterial taxa and their abundances in the gut samples from different treated groups. CA was conducted with “FactoMineR” package in R.

Data availability

All sequence information has been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (project number PRJNA1114793).

References

Wright, G. A., Nicolson, S. W. & Shafir, S. Nutritional physiology and ecology of honey bees. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 63, 327–344 (2018).

VanEngelsdorp, D., Hayes, J., Underwood, R. M. & Pettis, J. A survey of honey bee colony losses in the US, fall 2007 to spring 2008. PLoS ONE. 3, e4071 (2008).

Bruckner, S. et al. A National survey of managed honey bee colony losses in the USA: results from the bee informed partnership for 2017–18, 2018–19, and 2019–20. J. Apic. Res. 62, 429–443 (2023).

Meixner, M. D. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the united States and the factors that May affect them. J. Invertebr Pathol. 103, S80–S95 (2010).

Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C. & Rotheray, E. L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347, 1255957 (2015).

Pudasaini, R., Dhital, B. & Chaudhary, S. Nutritional requirement and its role on honeybee: a review. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 3, 321–334 (2020).

Thompson, K. & Drew, B. T. Supplemental feeds and foraged corn grain dust: a comparison of the number of days survived in vitro by young adult honey bees (Apis mellifera). J. Apic. Res. 61, 1–8 (2022).

Paray, B. A. et al. Honeybee nutrition and pollen substitutes: a review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 1167–1176 (2021).

Barker, R. J. & Lehner, Y. Laboratory comparison of high Fructose corn syrup, grape syrup, honey, and sucrose syrup as maintenance food for caged honey bees. Apidologie 9, 111–116 (1978).

Severson, D. W. & Erickson, E. H. Honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colony performance in relation to supplemental carbohydrates. J. Econ. Entomol. 77, 1473–1478 (1984).

Brodschneider, R. & Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 41, 278–294 (2010).

Ahmad, S., Khan, S. A., Khan, K. A. & Li, J. Novel insight into the development and function of hypopharyngeal glands in honey bees. Front. Physiol. 11, 615830 (2021).

DeGrandi-Hoffman, G., Chen, Y., Huang, E. & Huang, M. H. The effect of diet on protein concentration, hypopharyngeal gland development and virus load in worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L). J. Insect Physiol. 56, 1184–1191 (2010).

Wahl, O. & Ulm, K. Influence of pollen feeding and physiological condition on pesticide sensitivity of the honey bee Apis mellifera Carnica. Oecologia 59, 106–128 (1983).

Taylor, M. A. et al. The effect of carbohydrate sources: sucrose, invert sugar and components of Mānuka honey, on core bacteria in the digestive tract of adult honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS ONE. 14, e0225845 (2019).

Ament, S. A., Corona, M., Pollock, H. S. & Robinson, G. E. Insulin signaling is involved in the regulation of worker division of labor in honey bee colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105, 4226–4231 (2008).

Seeley, T. D. & Visscher, P. K. Survival of honeybees in cold climates: the critical timing of colony growth and reproduction. Ecol. Entomol. 10, 81–88 (1985).

Kunert, K. & Crailsheim, K. Seasonal changes in carbohydrate, lipid and protein content in emerging worker honeybees and their mortality. J. Apic. Res. 27, 13–21 (1988).

Phillips, E. F. The utilization of carbohydrates by honeybees. U S Gov. Print. Off (1927).

Abdella, M., Rateb, S. H., Khodairy, M. M. & Omar, E. M. Sucrose, glucose, and Fructose preference in honeybees and their effects on food digestibility. Apidologie 55, 77 (2024).

Sammataro, D. & Weiss, M. Comparison of productivity of colonies of honey bees, Apis mellifera, supplemented with sucrose or high Fructose corn syrup. J. Insect Sci. 13, 19 (2013).

Akgün, N., Çelik, Ö. F. & Kelebekli, L. Physicochemical properties, total phenolic content, and antioxidant activity of chestnut, rhododendron, acacia and multifloral honey. J. Food Meas. Charact. 15, 3501–3508 (2021).

Baek, Y., Kim, Y. J., Baik, M. Y. & Kim, D. O. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of Korean domestic honey from different floral sources. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 24, 1453–1457 (2015).

Brouwers, E. V. M. Activation of the hypopharyngeal glands of honeybees in winter. J. Apic. Res. 22, 137–141 (1983).

Crailsheim, K. & Stolberg, E. Influence of diet, age and colony condition upon intestinal proteolytic activity and size of the hypopharyngeal glands in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L). J. Insect Physiol. 35, 595–602 (1989).

Babendreier, D. et al. Influence of Bt-transgenic pollen, Bt-toxin and protease inhibitor (SBTI) ingestion on development of the hypopharyngeal glands in honeybees. Apidologie 36, 585–594 (2005).

Jang, H. et al. Chlorella-supplemented diet improves the health of honey bee (Apis mellifera). Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 922741 (2022).

Ikeya, T., Galic, M., Belawat, P., Nairz, K. & Hafen, E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 12, 1293–1300 (2002).

Campbell, M. K. & Farrell, S. O. Biochemistry 8th edn (Cengage Learning, 2015).

Amdam, G. V. Social context, stress, and plasticity of aging. Aging Cell. 10, 18–27 (2011).

Corona, M. et al. Vitellogenin, juvenile hormone, insulin signaling, and queen honey bee longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104, 7128–7133 (2007).

Nilsen, K. A. et al. Insulin-like peptide genes in honey bee fat body respond differently to manipulation of social behavioral physiology. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 1488–1497 (2011).

Ortiz-Alvarado, Y. et al. Antibiotics in hives and their effects on honey bee physiology and behavioral development. Biol. Open. 9, bio053884 (2020).

Broughton, S. J. et al. Longer lifespan, altered metabolism, and stress resistance in drosophila from ablation of cells making insulin-like ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 3105–3110 (2005).

Harrison, J. F. & Fewell, J. H. Environmental and genetic influences on flight metabolic rate in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 75, 323–333 (2002).

Corby-Harris, V. & Snyder, L. A. Measuring hypopharyngeal gland acinus size in honey bee (Apis mellifera) workers. J. Vis. Exp. 139, e58261 (2018).

Pirini, A., Conte, L. S., Francioso, O. & Lercker, G. Capillary gas chromatographic determination of free amino acids in honey as a means of discrimination between different botanical sources. J. High. Resolut Chromatogr. 15, 165–170 (1992).

Quinlan, G. et al. Carbohydrate nutrition associated with health of overwintering honey bees. J. Insect Sci. 23, 16 (2023).

Jones, J. C. et al. Gut microbiota composition is associated with environmental landscape in honey bees. Ecol. Evol. 8, 441–451 (2018).

Kwong, W. K. et al. Dynamic Microbiome evolution in social bees. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600513 (2017).

Ellegaard, K. M. & Engel, P. Genomic diversity landscape of the honey bee gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 10, 446 (2019).

Kešnerová, L. et al. Gut microbiota structure differs between honeybees in winter and summer. ISME J. 14, 801–814 (2020).

Engel, P., Bartlett, K. D. & Moran, N. A. The bacterium Frischella Perrara causes scab formation in the gut of its honeybee host. mBio 6, e01012–e01015 (2015).

Emery, O., Schmidt, K. & Engel, P. Immune system stimulation by the gut symbiont Frischella Perrara in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Mol. Ecol. 26, 2576–2590 (2017).

Engel, P., Kwong, W. K. & Moran, N. A. Frischella Perrara gen. Nov., sp. Nov., a gammaproteobacterium isolated from the gut of the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 3646–3651 (2013).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable, and extensible Microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the BSRP through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AN conceived the study and wrote the early draft of the manuscript. SMN helped to design the gene expression and gut microbiome studies and conducted the bioinformatics analysis. SG had a significant contribution in gene expression study design and discussed the results of gene expression and microbiome analysis. CJ provided financial support for the study and supervised this research. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Najarpoor, A., Mohamadzade Namin, S., Ghosh, S. et al. Impact of carbohydrate sources on the longevity and physiological traits of the European honey bee workers. Sci Rep 15, 29532 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15325-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15325-w