Abstract

Periodontitis is a common inflammatory disease affecting the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth, ultimately leading to tooth loss if left untreated. This study aimed to investigate the diagnostic potential of lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) and characterize the immune microenvironment landscape in periodontitis. Differential expression analysis identified differentially expressed LMRGs (DELMRGs), followed by functional enrichment analyses to elucidate their biological functions. Hub DELMRGs were identified using Random Forest, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, and XGBoost. The diagnostic performance of these genes was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Immune cell infiltration and immune function status were analyzed using ImmuCellAI and Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA), respectively. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was employed to decode the immune microenvironment and cell communication networks at single-cell resolution in periodontitis. Machine learning approaches revealed five hub LMRGs: FABP4, CWH43, CLN8, ADGRF5, and OSBPL6. ADGRF5 and FABP4 were significantly upregulated in periodontitis samples, while CWH43, CLN8, and OSBPL6 were downregulated. The combined LMRGs score exhibited excellent diagnostic performance with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.954. Immune cell infiltration analysis unveiled significant positive correlations between LMRGs score and various T cell subsets in periodontitis. GSVA indicated activation of antigen presentation processes and multiple immune-related pathways in periodontitis. scRNA-seq delineated eight distinct cell types, with key LMRGs differentially expressed across cell types. Cell communication analysis highlighted significant interactions mediated by MHC-II, CXCL, and ADGRE5 signaling pathways. Monocytes and multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs) primarily contributed to the inflammatory response. Further analysis of monocyte heterogeneity identified five monocyte clusters with distinct roles, including immune and inflammatory response activation and pathways related to cell proliferation and metabolism.In summary, the integrated LMRGs score, which reflects lipid metabolism’s role, represents a promising diagnostic biomarker for periodontitis. Additionally, detailed immune cell infiltration and single-cell analyses underscored the critical role of the immune microenvironment in periodontitis pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Periodontitis is a common inflammatory disease affecting the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth, ultimately leading to tooth loss if left untreated1. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), periodontal disease ranks as the sixth most prevalent disease in humans2,3. Severe periodontitis impacts around 11% of the global population, highlighting its status as a worldwide epidemic2. Despite significant advancements in understanding the microbial etiology of periodontitis, the precise molecular mechanisms underpinning its pathogenesis remain inadequately elucidated. Emerging evidence suggests that lipid metabolism plays a crucial role in the regulation of inflammatory responses, thereby influencing the progression of various chronic inflammatory diseases, including periodontitis4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, the specific contributions of lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) to periodontitis have not been thoroughly investigated.

The immune microenvironment in periodontitis is complex and involves various immune cells, cytokines, and chemokines that interact in a dynamic network6,11,12. This microenvironment not only responds to bacterial insults but also modulates the progression of tissue inflammation and destruction12,13. A deeper understanding of the immune microenvironment and its interaction with lipid metabolism could provide new insights into the pathogenesis of periodontitis and identify potential therapeutic targets. With advancements in high-throughput technologies, such as RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), it is now possible to profile the entire transcriptome of periodontal tissues, providing comprehensive insights into gene expression changes associated with disease states. Additionally, the integration of machine learning approaches in bioinformatics allows for the analysis of complex biological data, facilitating the identification of key genes and pathways involved in disease processes14,15.

In this study, we aim to investigate the diagnostic potential of LMRGs and decipher the immune microenvironment in periodontitis based on machine learning and transcriptional data analysis. By leveraging RNA-seq data from periodontal tissues, we seek to identify differentially expressed genes associated with lipid metabolism. Machine learning algorithms will be employed to analyze and interpret the large datasets, identifying potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets. By employing state-of-the-art machine learning techniques and comprehensive transcriptional analysis, we aim to uncover novel insights into the molecular underpinnings of periodontitis, potentially paving the way for the development of targeted therapies that could ameliorate or prevent the progression of this debilitating disease.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This study aimed to explore the involvement of LMRGs and the immune microenvironment in periodontitis through the analysis of transcriptional data using machine learning techniques. Bulk RNA-seq data from periodontitis and healthy individuals were sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, specifically the GSE16134 and GSE10334 datasets16,17. The GSE16134 dataset comprises RNA-seq data from 310 gingival tissues, with 241 samples collected from diseased sites and 69 from healthy sites. Similarly, the GSE10334 dataset includes RNA-seq data from 247 gingival samples, with 183 samples from diseased sites and 64 from healthy sites. In this study, the GSE16134 dataset served as the training dataset for identifying hub LMRGs distinguishing between periodontitis and healthy individuals, while the GSE10334 dataset was utilized as an external validation cohort. Raw data underwent normalization for subsequent analyses, with quality control measures implemented to remove samples with low read counts and normalize gene expression levels across all samples. Additionally, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data were obtained from the GSE152042 dataset18 comprising four scRNA-seq datasets from gingival tissue samples of two periodontitis patients and two healthy individuals.

Differentially expressed genes identification and functional enrichment analysis

A total of 1454 LMRGs were identified according to previous studies19,20,21,22,23. Differential expression analysis was performed using the limma package in R. Genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and a |log2 fold change (FC)| > 0.585 were considered differentially expressed. Heatmaps and volcano plots were generated using the pheatmap and ggplot2 packages in R to visualize the expression patterns of DELMRGs. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were conducted using the clusterProfiler package in R to investigate the biological functions and pathways associated with upregulated and downregulated LMRGs.

Key lipid metabolism related genes identification by machine learning framework

Three machine learning algorithms were employed to identify key diagnostic LMRGs, including Random Forest (RF), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression, and XGBoost. RF was implemented using the randomForest package, LASSO regression using the glmnet package, and XGBoost using the xgboost package in R. Importance scores and coefficients were calculated to rank the genes. Hub genes were identified based on their consistent selection across all three algorithms. Expression levels of the identified hub genes were compared between periodontitis and healthy samples using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated using the pROC package to evaluate the diagnostic performance of each gene. Delong test was adopted to estimate the 95% confidence interval of ROC curves24. An LMRGs score was developed by combining the expression levels of the hub genes using a linear regression model. The diagnostic ability of the LMRGs score was validated in an external cohort using the same statistical methods.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Immune cell infiltration was estimated using the ImmuCellAI algorithm, which provides the proportions of various immune cell types in each sample25. Immune function status was assessed using Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) with the GSVA package. Correlations between LMRGs scores and immune cell infiltration levels were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation. The Wilcoxon test was employed to assess the statistical differences in immune cell infiltration and immune function scores between periodontitis and healthy participants.

Single-Cell RNA sequencing analysis

Quality control of scRNA-seq data was performed using the Seurat package in R to filter out cells with low gene counts, high mitochondrial gene expression, or other indicators of poor-quality data by referencing previously published study26. Following quality control, the data were normalized and scaled. t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) was used to reduce dimensionality and visualize the data. Cell annotation was performed using SingleR, which uses reference transcriptomic datasets to identify and label cell types in the scRNA-seq data. This allowed for the classification of cells into distinct populations based on their expression profiles. Cell communication analysis was conducted using CellChat27 a tool that infers intercellular communication networks by analyzing the expression of ligand-receptor pairs. This analysis provided insights into the signaling interactions between different cell types in periodontitis and healthy samples. Single-cell Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using the irGSEA package to identify pathways and biological processes enriched in different cell populations. Additionally, GSVA was used to investigate immune-related pathways in different cell types by employing hallmark gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). Pseudotime analysis, conducted using the Monocle package28 was used to infer the trajectory of monocyte differentiation and to identify key transitional states and genes involved in these processes. The detailed process of scRNA-seq analysis was referred to previously publication26.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

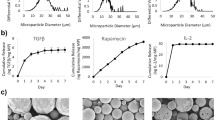

Gingival tissue samples were collected from patients with periodontitis, as well as corresponding healthy gingival tissues from control subjects, at the Department of Stomatology, Northwest University First Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to sample collection. The study protocol was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee (Ethics Approval No.: 2024KY-04) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of protein expression, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval using citrate buffer. After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies targeting FABP4 (#GB115466, Servicebio), CWH43 (#ER1906-83, HUABIO), CLN8 (#ER1906-44, HUABIO), ADGRF5 (#14047-1-AP, Proteintech), and OSBPL6 (#ab96286, Abcam). The sections were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Protein signals were detected using DAB chromogen substrate, and the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. The stained slides were observed under a light microscope to evaluate the protein expression levels of the target genes in gingival tissues from periodontitis patients and healthy controls.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R. Differences between groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed data and the t-test for normally distributed data. Correlation analyses were conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation. P-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method, and adjusted P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Identification of differentially expressed lipid metabolism related genes between periodontitis and healthy individuals

The workflow of this study is display in Fig. 1A. A total of 74 differentially expressed lipid metabolism-related genes (DELMRGs) were identified through differential expression analysis. Among these, 44 genes were upregulated, while 30 genes were downregulated (Fig. 1B). The hierarchical clustering heatmap shows the detailed expression patterns of these DELMRGs (Fig. 1C). We then investigated the biological functions of the upregulated and downregulated LMRGs using GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. GO enrichment analysis revealed that the upregulated LMRGs were primarily involved in the phospholipid metabolic process, lipid catabolic process, regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity, regulation of inflammatory response, and regulation of lipid kinase activity (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the downregulated LMRGs were mainly associated with membrane lipid metabolism, membrane lipid biosynthesis, sphingolipid metabolism and biosynthesis, and fatty acid metabolism (Fig. 1F). KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the upregulated LMRGs were significantly involved in the chemokine signaling pathway, phospholipase D signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, NF-kappa B signaling pathway, and ether lipid metabolism (Fig. 1E). Meanwhile, the downregulated genes were primarily associated with arachidonic acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 1G).

Identification of differentially expressed lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) in periodontitis and healthy individuals. (A) The workflow of this study. (B–C) Volcano plot (B) and hierarchical clustering heatmap (C) illustrating the 74 differentially expressed LMRGs in periodontitis and healthy individuals. (D–E) Significant terms of GO (Gene Ontology) enrichment analysis (D) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis (E) of the 44 upregulated LMRGs. (F–G) Significant terms of GO enrichment analysis (F) and KEGG enrichment analysis (G) of the 30 downregulated LMRGs.

Hub lipid metabolism related genes identification by multiple machine learning approaches

Next, three machine learning algorithms were employed to identify the most relevant diagnostic LMRGs for periodontitis. Random Forest (RF) identified 10 LMRGs based on importance scores, including FABP4, PLEKHA1, CWH43, CLN8, PDGFD, NEU1, HMGCR, CYP24A1, and OSBPL6 (Fig. 2A, B). Using LASSO regression, 16 LMRGs were identified after selecting the appropriate penalty parameter (Fig. 2C, D), with the coefficients of these genes shown in Fig. 2E. In the XGBoost model, the top 10 important LMRGs were CWH43, RORA, HSD11B1, PLEKHA1, ADGRF5, CLN8, FABP4, LYN, ENPP2, and OSBPL6 (Fig. 2F). Ultimately, five hub LMRGs were identified across these three algorithms: FABP4, CWH43, CLN8, ADGRF5, and OSBPL6 (Fig. 2G). We then explored the expression levels of these genes between periodontitis and healthy samples in the GSE16134 dataset. ADGRF5 and FABP4 were significantly upregulated in periodontitis samples compared to healthy tissues (Fig. 2H). Conversely, the expression levels of CWH43, CLN8, and OSBPL6 were significantly higher in healthy tissues than in periodontitis samples (Fig. 2H).

Identification of hub lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) as promising diagnostic biomarkers for periodontitis through machine learning framework. (A–B) Variable selection in the Random Forest algorithm. (A) Line plot illustrating the relationship between the number of trees and the misclassification rate and out-of-bag (OOB) error in the Random Forest model. (C–E) Variable selection in the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression model. (C) The variable selection process during LASSO regression, with the horizontal axis representing the penalized parameter lambda (log-transformed) and the vertical axis showing the coefficients of each variable. (D) The 10-fold cross-validation (CV) of the LASSO model. The blue line represents the value of lambda and the corresponding variable number with non-zero coefficients selected by lambda.1se, while the red line represents the value of lambda and the corresponding variable number with non-zero coefficients selected by lambda.min. (E) Bar plot displaying the coefficients of the LMRGs identified by LASSO regression. (F) The importance score of the top 10 variables identified by the XGBoost model. (G) Venn plot illustrating the common LMRGs identified by the three machine learning algorithms. (H–I) Facet boxplots (H) and receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curves (I) to demonstrate the expression pattern and diagnostic ability of key LMRGs in periodontitis. (J–K) Boxplots (J) and ROC curve (K) showing the expression pattern and diagnostic ability of the LMRGs score in periodontitis.

Subsequently, ROC curves were used to evaluate the diagnostic ability of these LMRGs in distinguishing between periodontitis and healthy participants. The results demonstrated that these genes performed well in differentiating periodontitis from healthy individuals (Fig. 2I). The AUC value for CWH43 was 0.898 (0.848 − 0.947), followed by OSBPL6 (0.894 [0.849 − 0.939]), CLN8 (0.864 [0.810 − 0.918]), ADGRF5 (0.855 [0.808 − 0.903]), and FABP4 (0.850 [0.794 − 0.906]) (Fig. 2I). To further enhance the diagnostic ability of these genes for periodontitis, we developed an LMRGs score using the following formula: LMRGs score = 1.137 * FABP4 + (-1.113) * CWH43 + (-1.701) * CLN8 + 2.403 * ADGRF5 + (-1.642) * OSBPL6. As expected, periodontitis patients had higher LMRGs scores than healthy individuals (Fig. 2J). Integrating these genes into one index further improved the diagnostic ability, with the LMRGs score yielding an excellent discrimination ability between periodontitis and healthy samples, with an AUC of 0.954 (0.919 − 0.988) (Fig. 2K). We also validated the expression levels and diagnostic ability of the identified hub LMRGs and LMRGs score in an external validation cohort, with consistent results observed (Figure S1A-D). Ultimately, we also validated the protein expression level of these hub genes in healthy and periodontitis human samples through IHC staining. The results indicated that CLN8, CWH43, and OSBPL6 were upregulated in periodontitis tissues, while ADGRF5 and FABP4 were upregulated in healthy tissues (Figure S2). Taken together, these results indicate that these LMRGs and their integrated index, the LMRGs score, have promising diagnostic ability for periodontitis.

Immune cell infiltration landscape and immune function status in patients with periodontitis

Next, we investigated immune cell infiltration and immune function in periodontitis using ImmuCellAI and GSVA. In the GSE16134 cohort, we observed multiple immune cells, including CD4 + T cells, Th17, follicular helper T cell (Tfh), nTreg, CD4 naive T cells, iTreg, Th1, Th2, dendritic cells (DC), exhausted T cells, and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3A). Consistent results were observed in the GSE10334 cohort (Fig. 3D). We then examined the association between LMRG scores and the infiltration levels of different immune cells in periodontitis and healthy tissues. A significant positive correlation was found between LMRG scores and the infiltration of CD4+ T cells, CD4 naive T cells, nTreg, Th1, Th17, Tfh, and exhausted T cells in periodontitis tissues in the GSE16134 dataset (Fig. 3B). In contrast, LMRG scores were significantly negatively correlated with the infiltration of macrophages and cytotoxic T cells (Fig. 3B). Similar correlation patterns were identified in healthy participants in the GSE16134 dataset (Fig. 3C) and all participants in the GSE10334 dataset (Fig. 3E, F). Boxplots demonstrated that periodontitis tissues had significantly higher infiltration levels of CD4+ T cells, Tfh, and Th17 than healthy tissues in both the GSE16134 and GSE10334 datasets (Fig. 3G, H). However, the infiltration levels of gamma delta T cells and macrophages in periodontitis were significantly decreased compared to healthy individuals (Fig. 3G, H).

Immune cell infiltration and immune function estimation in periodontitis. (A–C) Hierarchical clustering heatmap (A) and correlation heatmap (B–C) illustrating the diverse immune cell infiltration status and their correlation with lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) in periodontitis and healthy individuals in the GSE16134 cohort. (D–F) Hierarchical clustering heatmap (D) and correlation heatmap (E–F) illustrating the diverse immune cell infiltration status and their correlation with LMRGs in periodontitis and healthy individuals in the GSE10334 cohort. (G–H) Boxplots demonstrating the differences in immune cell infiltration estimated by ImmuneCellAI between periodontitis and healthy individuals in the GSE16134 (G) and GSE10334 (H) datasets. (I) Significant altered biological processes in periodontitis identified by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). ns no significance; * P-value < 0.05; ** P-value < 0.01; *** P-value < 0.0001.

GSVA was performed to investigate immune function in periodontitis. The results indicated that antigen presentation processes were significantly activated in periodontitis, as evidenced by increased scores for APC co-stimulation, HLA, and aDCs (Figures SA, B). This further triggered T cell activation and inflammation responses in periodontitis, as indicated by the increased scores of multiple T cell subsets and the inflammation-promoting score in GSVA (Figure S3A, B). GSEA was then employed to investigate significantly altered biological processes and pathways between periodontitis and healthy participants. Consistent with the GSVA analysis, multiple immune-related processes and inflammation response-related pathways were significantly activated in periodontitis, as evidenced by the activation of inflammatory response, TNF-α signaling via NF-κB, IL2-STAT5 signaling, IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, and chemokine signaling pathways (Fig. 3I and Figure S4A). Furthermore, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, apoptosis, and metabolism pathways were also significantly activated in periodontitis (Fig. 3I and Figure S4A). Collectively, these results revealed that the immune microenvironment plays pivotal roles in periodontitis.

scRNA-seq analysis identifies cell subtypes and cell communication in periodontitis

Considering the limitations of bulk RNA-seq data in reflecting the immune microenvironment components in patients, we performed scRNA-seq analysis to decipher the immune microenvironment of periodontitis at single-cell resolution. After quality control and dimensionality reduction, we identified 12 distinct clusters in both periodontitis and healthy gingival tissue (Fig. 4A and Figure S4B). The top five marker genes of each cluster were visualized using bubble plots (Fig. 4B) and heatmaps (Figure S4C). Ultimately, using the SingleR algorithm, we identified eight main cell types among the 12 clusters: plasma cells, monocytes, multipotent progenitor cells (MPP), fibroblasts, keratinocytes, CD8+ effector memory T cells (Tem), microvascular (mv) endothelial cells, and class-switched memory B cells (Fig. 4C). We then validated the expression levels of key LMRGs at the single-cell level. Our analysis revealed that ADGRF5 and FABP4 were primarily expressed in fibroblasts and microvascular endothelial cells, while CLN8 was expressed across all single-cell types. In contrast, OSBPL6 was not expressed in CD8+ Tem cells, plasma cells, or monocytes (Fig. 4D and Figure S5A-C). Subsequently, we mapped the cell communication network among these cell types, identifying strong interactions mediated by multiple signaling pathways, including MHC-II signaling, CXCL signaling, and ADGRE5 signaling (Fig. 4E). These pathways are crucial in antigen processing and the inflammatory response. Further investigation of these pathways revealed that HLA and CD4 primarily contributed to signaling from various cells to MPP (Figure S6A), CXCL12 and CXCR4 contributed to signaling from plasma cells to other cells (Figure S6B), and ADGRE5 and CD55 contributed to signaling from diverse cells (Figure S6C).

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis in periodontitis to decipher its immune microenvironment landscape. (A) The utilization of the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tsne) algorithm identified 12 clusters in gingival tissues from individuals with periodontitis and healthy individuals. (B) Dot plot visualization of the top five marker genes for each cluster. (C) Annotation of eight cell types in gingival tissues from individuals with periodontitis and healthy individuals. (D) Feature plots displaying the expression levels of hub lipid metabolism-related genes (LMRGs) across the cell subtypes. (E) Cell communication network and the contribution of MHC-II, CXCL, and ADGRE5 signaling among different cell types. (F) Ridge plots displaying the indicated biological pathway scores estimated by single-cell Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) among different cell types.

Single-cell GSEA was performed to investigate the most relevant biological functions of different cell subtypes in periodontitis. The results suggested that monocytes and MPPs primarily contributed to the inflammatory response and immune reaction in periodontitis by activating pathways such as the inflammatory response, TNF-α signaling via NF-κB, IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, IL2-STAT5 signaling, complement, and reactive oxygen species pathways (Figure S6D). Fibroblasts were mainly involved in processes like EMT, myogenesis, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Figure S6D). Keratinocytes and mv endothelial cells were engaged in cell proliferation by activating the E2F targets, MYC targets V1, and MYC targets V2 pathways (Figure S6D). We further performed single-cell GSEA to investigate the significantly altered biological processes of these cell types in periodontitis. Consistent with previous findings, the results indicated that the IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, inflammatory response pathway, TNF-α signaling via NF-κB, and interferon gamma response pathways were significantly activated in monocytes (Fig. 4F and Figure S6D). Meanwhile, EMT was exclusively activated in fibroblasts. The process of adipogenesis was activated in multiple cell types in periodontitis, except for CD8+ Tem and class-switched memory B cells (Fig. 4F and Figure S6D). Taken together, these findings highlight the important role of monocytes in periodontitis through the activation of inflammatory response pathways.

Deciphering the heterogeneity among different monocytes clusters in periodontitis

Given the important role and heterogeneity of monocytes in periodontitis, we further investigated the role of different subsets of monocytes by clustering them into distinct groups. Using the t-SNE algorithm, we identified five monocyte clusters, with the top five marker genes for each cluster summarized in Fig. 5A. Based on the unique expression patterns of these marker genes (Figure S7), we annotated the monocyte clusters as follows: C1 (APOE+SELENOP+ monocytes), C2 (CD1E+ monocytes), C3 (GZMB+PTGDS+ monocytes), C4 (CLEC9A+ monocytes), and C5 (IGHA1+ monocytes) (Fig. 5B). Trajectory analysis revealed three differentiation states among these monocyte subtypes. C1 represented the earliest stage of differentiation, while C4 appeared at the terminal stage (Fig. 5C). Additionally, BEAM analysis was conducted to investigate differentially expressed genes (DEGs) before and after branch point 1. We identified the top 100 DEGs, categorizing them into three subtypes as shown in Fig. 5D.

Deciphering the heterogeneity of monocytes in periodontitis through single-cell analysis. (A) Dot plot visualization of the top five marker genes for each monocyte cluster. (B) Annotation of five monocyte subtypes based on their unique marker genes. (C) Cell trajectory and pseudotime analysis among monocyte subtypes. (D) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of branch 1 along the pseudotime were hierarchically clustered into three subclusters, and their biological functions were estimated by Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap showcasing the activity of diverse biological processes among different monocyte subtypes.

GO enrichment analysis demonstrated that DEGs in cluster 1 were mainly involved in neutrophil activation, inflammatory response, and immune response. DEGs in cluster 2 were primarily associated with signal peptide processing, while DEGs in cluster 3 were linked to antigen presentation and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 5D). We further performed GSVA to explore the significantly altered biological processes in these monocyte subtypes. As illustrated in Fig. 5E, clusters C1 and C2 were predominantly involved in immune and inflammatory response pathways (Fig. 5E). Additionally, the EMT process was activated in C1 and C2 monocytes (Fig. 5E). In contrast, cell proliferation, adipogenesis, fatty acid metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation were activated in C3, C4, and C5 monocytes (Fig. 5E). Single-cell GSEA was conducted to validate these findings, with consistent results observed (Figure S8). Taken together, different monocyte subtypes have distinct roles in periodontitis.

Discussion

In this study, we performed a comprehensive analysis to elucidate the role of LMRGs in periodontitis. Our results identified 74 DELMRGs, with 44 upregulated and 30 downregulated, highlighting significant alterations in lipid metabolism in periodontitis. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed that these genes are involved in critical pathways, including the phospholipid metabolic process, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, and arachidonic acid metabolism. These findings align with previous studies indicating the importance of lipid metabolism in inflammatory diseases and suggest that lipid metabolic dysregulation may contribute to the pathogenesis of periodontitis4,5,6,7. Nicchio et al. investigated the association of polymorphisms in genes relevant to lipid metabolism with the occurrence of periodontitis in a case-control study7. They found that the rs1042031 SNP in the APOB gene and the rs6544718 SNP in the ABCC8 gene were associated with a significantly lower risk of periodontitis7. Matsumoto and colleagues examined the relationship between the lipid metabolism-related gene, lipase-a, and the occurrence of aggressive periodontitis through a genome-wide association study (GWAS)8. Their research revealed that the lipase-a SNP rs143793106 is associated with an increased risk of aggressive periodontitis due to its negative impact on the cytodifferentiation of human periodontal ligament cells8. Despite these findings, no study has systematically characterized the role of LMRGs in periodontitis based on transcriptional analysis.

The integration of machine learning algorithms provided a robust approach to identifying hub LMRGs with potential diagnostic value. The intersection of results from RF, LASSO, and XGBoost models highlighted five key genes: FABP4, CWH43, CLN8, ADGRF5, and OSBPL6. The differential expression patterns of these genes between periodontitis and healthy samples were validated in the GSE16134 dataset, with ADGRF5 and FABP4 being upregulated in periodontitis, while CWH43, CLN8, and OSBPL6 were downregulated. The diagnostic potential of these hub genes was further affirmed through ROC curve analysis, with high AUC values indicating excellent discriminatory power. The LMRGs score developed in this study, integrating the expression levels of these five hub genes, demonstrated superior diagnostic ability with an AUC of 0.954. These results suggest that these hub genes, particularly in combination, could serve as robust biomarkers for periodontitis diagnosis. ADGRF5, identified as a novel member of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family in 1999, has been increasingly recognized for its role in metabolism regulation29,30,31,32. However, no prior studies have investigated the expression and role of ADGRF5 in periodontitis. FABP4, a critical adipokine, plays a significant role in the progression of systemic diseases33. Recent research indicated that periodontal pathogens can stimulate lipid uptake in macrophages by modulating FABP4 expression33. CWH43 is involved in the synthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors, which attach to the C-terminus of proteins and facilitate their delivery to the external side of the plasma membrane34. While CWH43’s role has been studied in colorectal cancer34its role in periodontitis remains poorly understood. Li and colleagues recently identified CLN8 as a novel LMRG regulating avian adipocyte differentiation35 but its role in periodontitis has not been explored. OSBPL6, a member of the oxysterol-binding protein-like (OSBPL) family, is crucial for lipid transportation and cholesterol balancing36. Recent studies have highlighted its role and prognostic value in liver cancer and Alzheimer’s disease37,38 but its role in periodontitis is still unclear. Therefore, there is an urgent need for further investigation into the roles of these hub LMRGs in periodontitis. Our study provides a preliminary clue, laying the groundwork for future research to elucidate their specific functions and mechanisms in the disease.

Periodontitis is a common oral disease closely related to immune response. Our investigation into the immune cell infiltration landscape revealed significant differences between periodontitis and healthy tissues. Periodontitis samples showed higher infiltration of CD4+ T cells and Th17 cells. These findings are consistent with the known pro-inflammatory immune response in periodontitis, characterized by T cell activation and cytokine production39. GSVA further highlighted the activation of multiple immune-related pathways, including the TNF-α signaling via NF-κB and IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, emphasizing the complex immune landscape in periodontitis. The scRNA-seq analysis provided deeper insights into the cellular heterogeneity and communication networks in periodontitis. The validation of key LMRG expression at the single-cell level and the mapping of cell communication networks suggested significant interactions mediated by pathways such as MHC-II signaling and CXCL signaling, which may contribute to antigen processing and the inflammatory response. In the current study, we identified that CXCL12-CXCR4 ligand and receptor pairs contribute to the CXCL pathway in periodontitis. Recently, Xu and colleagues revealed that CXCR4/CXCL12 signal axial might contribute to the development of periodontitis by mediating neutrophil dynamics40. Notably, monocytes exhibited significant heterogeneity, with five distinct clusters identified. The trajectory and functional analyses revealed that early differentiation states of monocytes were primarily involved in immune and inflammatory responses, whereas later states were linked to cell proliferation and metabolism. However, it is important to note that while our findings suggest potential involvement of LMRG in immune signaling pathways, the direct relationship between LMRG expression and monocyte-mediated immunity remains speculative and requires further investigation. Recent studies, such as those by Gong et al.41 have highlighted the heterogeneity of monocyte populations in inflammatory conditions, underscoring the dynamic role of monocytes in disease progression. These insights provide a foundation for future research exploring the specific contributions of LMRG to monocyte-mediated immunity and their potential as therapeutic targets42,43.

The identified LMRGs and their association with altered lipid metabolism provide new insights into the potential mechanisms underlying the development and progression of periodontitis. Lipid metabolism plays a critical role in regulating inflammatory responses and immune cell function, both of which are central to pathogenesis of periodontitis44. Dysregulated lipid metabolism can lead to the overproduction of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which exacerbate inflammation and tissue destruction45. The identified LMRGs, such as those involved in the CXCL signaling pathway, may regulate lipid signaling and immune cell recruitment, suggesting a potential link between lipid metabolism and monocyte/macrophage function in the periodontal environment. Additionally, recent studies have shown that lipid metabolism dysregulation can alter macrophage polarization, shifting the balance toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype that contributes to chronic inflammation and tissue damage in periodontitis46. In this study, LMRGs may act as key regulators of lipid metabolic pathways, influencing the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory lipid mediators. Future animal models and in vitro experiments should further investigate the functional analyses of LMRGs in lipid metabolic pathways and their impact on immune cell behavior and inflammatory responses.

The evaluation of LMRG gene expression presents several potential advantages for the diagnosis of periodontitis. One significant benefit is its potential to detect disease at an earlier stage compared to traditional diagnostic methods, such as clinical probing depth or radiographic assessments, which often identify the disease only after significant tissue damage has occurred. Additionally, LMRG gene expression analysis may provide a more precise understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying periodontitis, enabling stratification of patients based on disease activity or progression risk. This could facilitate personalized treatment approaches, improving patient outcomes by tailoring interventions to the specific molecular profile of the disease. Although LMRG gene expression analysis offers unique advantages in terms of early detection and molecular insights, however, there are challenges to the clinical application of LMRG gene expression analysis due to the complexity and cost of gene expression measurements. Therefore, its current limitations in feasibility and utility must be addressed in the future before widespread adoption in clinical practice.

Despite the comprehensive nature of our study, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, our findings are primarily based on bioinformatic analyses and require experimental validation in larger, independent cohorts in the future. In addition, although we confirmed the expression patterns and diagnostic potential of the hub LMRGs in both external validation cohorts and clinical samples, further experimental studies are needed to investigate their functional roles and underlying mechanisms in regulating lipid metabolism and interacting with the immune microenvironment in periodontitis. Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to infer causal relationships between LMRGs and periodontitis. Longitudinal studies are needed to elucidate the temporal dynamics of these gene expressions and their role in disease progression. Additionally, while scRNA-seq provides valuable insights into the cellular landscape and immune microenvironment, our analysis was limited by the relatively small number of periodontitis and healthy samples available in existing datasets. A larger cohort would help refine the identification and characterization of rare or functionally important cell types, and provide a more comprehensive understanding of immune heterogeneity in periodontitis. Future studies incorporating expanded and more diverse sample sets, as well as leveraging advanced single-cell technologies, are warranted to address these important questions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides a comprehensive analysis of LMRGs expression in periodontitis, revealing significant alterations in gene regulation and associated pathways. The identification of hub LMRGs with high diagnostic potential, validated through multiple machine learning approaches, offers promising biomarkers for periodontitis. The detailed investigation of immune cell infiltration and single-cell analysis highlights the critical role of the immune microenvironment in periodontitis pathogenesis. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying periodontitis but also pave the way for the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies targeting lipid metabolism and immune responses in periodontal disease.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, GSE16134, GSE10334, and GSE152042) databases.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- DELMRGs:

-

Differentially expressed lipid metabolism-related genes

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- FC:

-

Fold change

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- GSVA:

-

Gene set variation analysis

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LMRGs:

-

Lipid metabolism-related genes

- MPPs:

-

Multipotent progenitor cells

- MSigDB:

-

Molecular signatures database

- RF:

-

Random forest

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- scRNA-seq:

-

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- Treg:

-

Regulatory T cells

- t-SNE:

-

t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

References

Könönen, E., Gursoy, M., Gursoy, U. K. & Periodontitis A multifaceted disease of Tooth-Supporting tissues. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081135 (2019).

Yang, H. et al. Exploring the potential link between MitoEVs and the immune microenvironment of periodontitis based on machine learning and bioinformatics methods. BMC Oral Health. 24, 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-03912-8 (2024).

Kassebaum, N. J. et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 93, 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514552491 (2014).

Jia, R. et al. Association between lipid metabolism and periodontitis in obese patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01366-7 (2023).

Ehteshami, A. et al. The association between high-density lipoproteins and periodontitis. Curr. Med. Chem. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867331666230726140736 (2023).

Guan, X. et al. Glucose and lipid metabolism indexes and blood inflammatory biomarkers of patients with severe periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. J. Periodontol. 94, 554–563. https://doi.org/10.1002/jper.22-0282 (2023).

Nicchio, I. G. et al. Polymorphisms in Genes of Lipid Metabolism Are Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontitis, as Comorbidities, and with the Subjects’ Periodontal, Glycemic, and Lipid Profiles. J. Diabetes Res. 2021 (1049307). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1049307 (2021).

Matsumoto, M. et al. Lipase-a single-nucleotide polymorphism rs143793106 is associated with increased risk of aggressive periodontitis by negative influence on the cytodifferentiation of human periodontal ligament cells. J. Periodontal Res. 58, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.13079 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Lipid metabolism-related gene signature predicts prognosis and depicts tumor microenvironment immune landscape in gliomas. Front. Immunol. 14, 1021678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1021678 (2023).

Thilagar, S. S., Yadalam, P. K., Ronsivalle, V., Minervini, G. & Cicciù M. and Prediction of interactomic HUB genes in periodontitis with acute myocardial infarction. J. Craniofac. Surg. 35, 1292–1297. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000010111 (2024).

Xu, X. W., Liu, X., Shi, C. & Sun, H. C. Roles of immune cells and mechanisms of immune responses in periodontitis. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 24, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.cjdr.b2440547 (2021).

Gasmi Benahmed, A. et al. Hallmarks of periodontitis. Curr. Med. Chem. https://doi.org/10.2174/0109298673302701240509103537 (2024).

Cekici, A., Kantarci, A., Hasturk, H. & Van Dyke, T. E. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 64: 57–80. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12002.

Zitnik, M. et al. Machine learning for integrating data in biology and medicine: principles, practice, and opportunities. Inf. Fusion. 50, 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2018.09.012 (2019).

Auslander, N., Gussow, A. B. & Koonin, E. V. Incorporating machine learning into established bioinformatics frameworks. International J. Mol. Sciences 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22062903

Papapanou, P. N. et al. Subgingival bacterial colonization profiles correlate with gingival tissue gene expression. BMC Microbiol. 9, 221. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-9-221 (2009).

Demmer, R. T. et al. Transcriptomes in healthy and diseased gingival tissues. J. Periodontol. 79, 2112–2124. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2008.080139 (2008).

Caetano, A. J. et al. Defining human mesenchymal and epithelial heterogeneity in response to oral inflammatory disease. Elife. 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62810.

Wu, J., Cai, H., Hu, X. & Wu, W. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the lipid metabolism-related gene regulatory characteristics and potential therapeutic agents for myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1281429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1281429 (2024).

Xu, M. et al. Screening of lipid Metabolism-Related gene diagnostic signature for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 853468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.853468 (2022).

Zheng, M. et al. Development and validation of a novel 11-Gene prognostic model for serous ovarian carcinomas based on lipid metabolism expression profile. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21239169 (2020).

Hao, Y. et al. Investigation of lipid metabolism dysregulation and the effects on immune microenvironments in pan-cancer using multiple omics data. BMC Bioinform. 20, 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-019-2734-4 (2019).

Jiang, A. et al. Lipid metabolism-related gene prognostic index (LMRGPI) reveals distinct prognosis and treatment patterns for patients with early-stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Med. Sci. 19, 711–728. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.71267 (2022).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988).

Miao, Y. R. et al. ImmuCellAI-mouse: a tool for comprehensive prediction of mouse immune cell abundance and immune microenvironment depiction. Bioinformatics 38, 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btab711 (2022).

Jiang, A. et al. Integration of Single-Cell RNA sequencing and bulk RNA sequencing data to Establish and validate a prognostic model for patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Genet. 13, 833797. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.833797 (2022).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using cellchat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9 (2021).

Trapnell, C. et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 381–386. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2859 (2014).

Jacenik, D., Hikisz, P., Beswick, E. J. & Fichna, J. The clinical relevance of the adhesion G protein-coupled receptor F5 for human diseases and cancers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1869, 166683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166683 (2023).

Georgiadi, A. et al. Orphan GPR116 mediates the insulin sensitizing effects of the hepatokine FNDC4 in adipose tissue. Nat. Commun. 12, 2999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22579-1 (2021).

Nie, T. et al. Adipose tissue deletion of Gpr116 impairs insulin sensitivity through modulation of adipose function. FEBS Lett. 586, 3618–3625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.006 (2012).

Frühbeck, G., Fernández-Quintana, B., Paniagua, M., Hernández-Pardos, A. W. & Moncada, V. V. FNDC4, a novel adipokine that reduces lipogenesis and promotes fat Browning in human visceral adipocytes. Metabolism - Clin. Experimental. 108 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154261 (2020).

Kim, D. J. et al. Periodontal pathogens modulate lipid flux via fatty acid binding protein 4. J. Dent. Res. 98, 1511–1520. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519880824 (2019).

Lee, C. C. et al. CWH43 is a novel tumor suppressor gene with negative regulation of TTK in colorectal cancer. International J. Mol. Sciences 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242015262

Li, X. et al. A novel candidate gene CLN8 regulates fat deposition in avian. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 14, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-023-00864-x (2023).

Olkkonen, V. M. OSBP-Related protein family in lipid transport over membrane contact sites. Lipid Insights. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4137/lpi.S31726 (2015).

Tian, K. et al. The expression, immune infiltration, prognosis, and experimental validation of OSBPL family genes in liver cancer. BMC Cancer. 23, 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10713-9 (2023).

Herold, C. et al. Family-based association analyses of imputed genotypes reveal genome-wide significant association of alzheimer’s disease with OSBPL6, PTPRG, and PDCL3. Mol. Psychiatry. 21, 1608–1612. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.218 (2016).

Ramadan, D. E., Hariyani, N., Indrawati, R., Ridwan, R. D. & Diyatri, I. Cytokines and chemokines in periodontitis. Eur. J. Dent. 14, 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1712718 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. CXCR4-mediated neutrophil dynamics in periodontitis. Cell. Signal. 111212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2024.111212 (2024).

Gong, Q. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing combined with proteomics of infected macrophages reveals prothymosin-α as a target for treatment of apical periodontitis. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.01.018 (2024).

Radics, T., Kiss, C., Tar, I. & Márton, I. J. Interleukin-6 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in apical periodontitis: correlation with clinical and histologic findings of the involved teeth. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 18, 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-302x.2003.180102.x (2003).

Torres-Monjarás, A. P. et al. Bacteria associated with apical periodontitis promotes in vitro the differentiation of macrophages to osteoclasts. Clin. Oral Investig. 27, 3139–3148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-023-04920-8 (2023).

Iacopino, A. M. & Cutler, C. W. Pathophysiological relationships between periodontitis and systemic disease: recent concepts involving serum lipids. J. Periodontol. 71, 1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2000.71.8.1375 (2000).

Dakal, T. C. et al. Lipids dysregulation in diseases: core concepts, targets and treatment strategies. Lipids Health Dis. 24, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02425-1 (2025).

Yan, J. & Horng, T. Lipid metabolism in regulation of macrophage functions. Trends Cell. Biol. 30, 979–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2020.09.006 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/design: SY; Collection and/or assembly of data: LW, MC; Data analysis and interpretation: LW, MC, XS, and YW; Manuscript writing: LW and MC; Final approval of manuscript: SY. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work is appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest University First Hospital (Approval No.: 2024KY-04). All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, L., Chen, M., Shi, X. et al. Exploring the role of lipid metabolism related genes and immune microenvironment in periodontitis by integrating machine learning and bioinformatics analysis. Sci Rep 15, 30008 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15330-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15330-z