Abstract

Grouting in fractured rock masses is crucial in numerous engineering projects such as tunnel seepage prevention, foundation reinforcement, and energy storage. However, slurry flow within fractures involves complex nonlinear behavior and significant fluid-solid coupling effects, and its accurate modeling remains a challenge. This study aims to establish a more accurate coupled model for slurry flow in fractures and rock mass deformation. Innovatively extending the Forchheimer formula for porous media to fracture flow, a nonlinear Forchheimer flow model suitable for power-law fluids is proposed, and pore and fracture flow are uniformly described by introducing a shape factor. Furthermore, by incorporating the constitutive relationship between slurry pressure and fracture deformation, a new numerical model for fluid-solid coupling of slurry in fractures is developed. Validation shows: compared with COMSOL numerical simulations, the average relative error of the calculation results for the two-phase flow model is less than 2.5%, with a deviation of only 1.1% for power-law turbulent flow velocity. When this method is used to detect slurry flow within a fracture network, the computational time is only 1/10 to 1/100 of that required by numerical methods, thus it ensures high computational accuracy while reducing computation time. Field case data indicate a prediction error of 7.26% for slurry diffusion distance. This model provides an effective tool for accurately predicting slurry diffusion behavior and fracture dynamic response during high-pressure grouting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Grouting has wide applications in various engineering fields, including oil and gas extraction1,2 hydrogeology3 groundwater development4 tunneling5,6 prevention and control of water hazards, anti-seepage measures for dams7 storage of energy and food8,9 and disposal of municipal and nuclear waste10,11 among others. Studying the flow characteristics of slurry in fractures allows for optimizing key parameters and evaluating the effectiveness of grouting projects based on the distance of slurry flow. This is essential for energy extraction12 pollution prevention, and disaster mitigation13,14.

In the mid-19th century, Darcy, a distinguished French hydraulic engineer, put forth the widely recognized Darcy’s law15. Building on this law, numerous flow models and numerical calculation methods have been developed by researchers16,17,18,19. That being said, the linear applicability of Darcy’s law to all types of flow isn’t always viable. Forchheimer20 drawing upon empirical observations of coalbed gas flow, introduced the renowned Forchheimer’s quadratic term, correlating the pressure gradient with the flow velocity in porous media.

Equation (1) is commonly applied to depict the nonlinear flow of Newtonian fluids21,22,23,24,25. However, a consensus has yet to be reached on determining the nonlinear parameter b, considering the multifaceted manifestations of nonlinearity. These encompass geometric nonlinearity induced by tortuous and blocked fracture channels, contractions and expansions of cross-section, and wall roughness26,27,28material nonlinearity brought about by non-Newtonian fluids contradicting the Newtonian law of internal friction29and motion nonlinearity triggered by localized turbulence when the fluid transitions into a turbulent state28,30,31.

Numerous experimental studies have confirmed that the transition from laminar flow to turbulent flow in turbulences32,33,34,35 can be characterized by the Reynolds number. It has been observed that, when the Reynolds number (Re) falls below 2000, the flow within capillary tubes remains laminar. Consequently, a correlation between the friction coefficient along the channel, the Reynolds number, and the channel’s relative roughness has been established.

Reynolds number is a similarity criterion number in fluid mechanics that represents the effect of viscosity. Nonetheless, in their investigation of Darcy’s flow, researchers have discovered that Darcy’s law is only verifiable at extremely low Reynolds numbers (ranging between 0 and 10). Once the Reynolds number surpasses 10, the correlation between pressure gradient and flow rate deviates markedly from Darcy’s linear law21,26,36. This deviation can be attributed to the nonlinearity of the geometry, which influences the fluid motion in a nonlinear manner, causing localized fluid to enter a “nonlinear flow state” prematurely as a result of vortex generation.

Existing literature on fracture flow predominantly employs the cubic law centered around steady laminar flow and its corresponding corrective equations. In the realm of hydraulic fracturing for example, power-law fluids have been examined by Garagash37turbulence has been explored by Zia and Lecampion38 among others, and flow non-linearity due to inertial effects with an extension providing an analytical solution for the coefficient b in Forchheimer’s equation for non-linearity in smooth and straight has been addressed by Gee and Gracie39. Nonetheless, during the majority of engineering applications, the injection pressure tends to be high and the slurry flow pattern frequently enters a nonlinear state. The current state of research still lacks a high-velocity non-Darcy flow model specifically designed for power law fluids in fractures, which can accurately depict the complete transition process from high-velocity non-Darcy flow to a linear flow state. Zou and Håkansson, et al.40 established a radial two-phase flow model of the yield power-law slurry in saturated fractures, and used analytical methods to predict the slug flow zone and propagation length. Jin and Han, et al.41 established a Forchheimer flow model for the cement slurry in static load fractures through experiments, and revealed the influence laws of water-to-cement ratio and normal load on the nonlinear coefficient. Liu and Yu, et al.42 quantified the normalized transmission rate of Newtonian fluids in rough fractures and the critical hydraulic gradient through the Navier-Stokes equation, and established a prediction model based on the fracture geometric parameters. Ding and Lei, et al.43 focused on the diffusion law of the slurry in the single fractures of the rock, established the Bingham fluid diffusion model for filling the fractures, and predicted the slurry movement by modifying the cubic law with the filling rate. Karem M and Hussein Abd et al.44 analyzed the mixed convection and chemical reactions of the power-law fluid on the stretched surface using the fifth-order finite difference method. Although this study has made progress in aspects such as the mechanism of slurry flow, the characterization of nonlinear coefficients, or the influence of geometric parameters, it generally did not involve the coupling mechanism of fracture deformation and slurry flow under high-pressure grouting conditions.

Consequently, this study introduces a Forchheimer equation, suitable for the turbulent movement of power-law fluids, taking into account both material and motion nonlinearities. A fluid-solid coupling model for injection grouting slurry has been crafted, factoring in the interaction between injection pressure and fractured rock mass. This particularly offers an effective computational and predictive approach for high-pressure injection grouting engineering endeavors.

Forchheimer’s law for parallel plate fractures

Given that the fluid pathways within the rock mass are understood to be constituted by numerous fracture channels45,46this study focuses on a single fracture for research implications. Meanwhile, the impact of geometric nonlinearity is temporarily excluded from consideration. It is hypothesized that the fractures are smooth and linear. The formula utilized for calculating pressure drop is rooted in47.

Among them, λ is the friction coefficient along the path; ρ is the density of the fluid (kg/m3); L is the length of the pipeline (m); D is the hydraulic diameter of the fracture (m), which is equal to twice the width of the fracture, D = 2b;b is the width of the fracture (m); v is the average flow velocity (m/s).

When the flow state of the fluid in the fracture is laminar (Re < 200), λ = 96/Re. Rewriting the power law48,49,50 in the form of Darcy’s law, we have:

Where k is the fracture permeability (m²), determined by the fracture geometry. For Newtonian fluids, k = D²/48. It can be easily proven that when the flow is laminar, Eq. (3) is equivalent to Eq. (4).

In instances where the fluid flow within a fracture is turbulent, defined by a Reynolds number (Re) between 400 and 100,000, the friction factor λ exhibits a correlation with Re. The scope of this discussion is solely based on channels presenting hydraulically smooth surfaces. As per Blasiu’s research51it has been established that channels with circular cross-sections adhere to the following relationship:

According to the shape factor function calculated by Conish52Eq. (5) is an approximate calculation formula obtained by the author.

In this equation, \(\phi (b/a)\)represents the shape factor between a rectangular (a×b) cross-section channel and a circular cross-section channel.

Equation (6) integrates a linear function with a half-period sine function, yielding a maximum error margin less than or equal to 0.25%. This margin of error is significantly smaller than the approximation proposed by Jones53 (refer to Fig. 1). By incorporating a shape factor, we can significantly streamline hydraulic calculations within rectangular channels. Furthermore, the shape factor provides improved precision in defining rock fractures. A clear exemplification of this application can be observed with laminar flow within parallel smooth fractures: given a fracture width to fracture opening ratio of 30:1, the permeability error, when using the shape factor against the cubic law, stands at 4.53%, which is well within acceptable engineering parameters. In light of this, we can ascertain whether the fluid channel model in experimental research could be simplified as fractures.

According to Eq. (6), the shape factor between the fracture section and the circular section can be obtained as 2/3. From the research of Jones53it is known that the along-flow resistance coefficient of the fracture section can still be calculated using Eq. (5), but it should be based on the relative Reynolds number Re*.

Where,

In addition, the permeability of the circular cross-section channel is defined as kc=D2/32. The permeability of the fracture also satisfies a conversion relationship, which is given by:

Therefore, analogously to porous media54,55,56 the Forchheimer equation for fractures can be written as:

Where, the nonlinear coefficient β can be expressed as,

In Eq. (10), the term µLv/k serves as a linear component indicative of the laminar flow state, while the term βρLv2/D stands as a nonlinear element influenced by turbulent flow. Inspection of Eq. (11) reveals that the nonlinear coefficient β can be interpreted as a form of resistance in fluid flow. Specifically, its value is null under laminar flow conditions and equals half of the discrepancy between the turbulent and laminar friction coefficients along the path of flow when the flow turns turbulent.

Forchheimer’s formula for fracture slurries

When the water-cement ratio of the grout is below 0.7, it can be considered as a power-law fluid57. Here, the study is conducted taking power-law fluids as an example. The constitutive equation for power-law fluids is as follows,

In the equation, τ represents the shear stress (Pa) within the fluid, K is the consistency coefficient (Pa·sn) of the power-law fluid, γ is the shear rate (s− 1), and n is the flow behavior index.

According to the research by Metzner and Reed58 the flow state of a power-law fluid can be determined using the Metzner-Reed Reynolds number (Repl). When Repl is less than 2000, the flow is classified as laminar flow.

The flow equation59 for laminar flow of a power-law fluid in a circular cross-section channel is given by:

Expressing Eq. (14) in the following form, resembling the Darcy equation:

From Eq. (15), it can be seen that the relationship between flow rate and pressure drop for a power-law fluid is not linear. The permeability of the power-law fluid flowing in a circular cross-sectional channel is given by:

When the flow transitions to a turbulent state, the Forchheimer model for power-law fluids was proposed.

By taking the 1/n-th power on both sides of Eq. (3), and combining it with Eq. (17), we can obtain the expression for the nonlinear coefficient.

Based on the previous analysis, the above equation can also be written as,

Where λ0 = 64/Repl, Eq. (19) further demonstrates the significance of βpl, which represents a difference between the non-linear friction factor and the linear friction factor.

The friction factor of power-law fluids can be calculated using the formula obtained from experiments by Dodge and Metzner60.

By combining the formula for laminar flow in fractured formations with power-law fluids, the shape factor for the flow of power-law slurries in fractures can be obtained.

Similarly, the relative Reynolds number (Re*pl) is to be used here.

For the convenience of calculation and application, the author further conducted an explicit fitting to Eq. (20) and obtained:

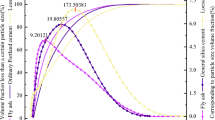

Figure 2 illustrates that when the rheological index n of the power-law fluid remains constant, mirroring Newtonian fluids, the friction factor λ diminishes with the rising Reynolds number Re along the flow direction. In instances where the Reynolds number is fixed, the friction factor escalates with the increase in the rheological index. When the rheological index n falls below 1, the fluid displays shear thickening behavior. As the Reynolds number grows, the shear rate follows suit, causing a rise in the fluid’s apparent viscosity and a pronounced fall in the friction factor. Conversely, when the rheological index n exceeds 1, the fluid reveals shear thinning behavior. With an increment in the Reynolds number, the fluid’s apparent viscosity drops, and the consequent decrease in the friction factor is gradual. If the rheological index n equals 1, the constitutive equation of the power-law fluid reduces to that of a Newtonian fluid. The friction factor also reveals that the friction factor curve under turbulent conditions (Eq. 7) for a Newtonian fluid serves as a specific instance of the power-law fluid (Eq. 23). Furthermore, during the calculation of following distinct cases, the friction factor in the transitional stage (2e3 < Re*pl< 4e3) is acquired through a linear interpolation method.

Upon determining the friction factor, the correlation between the nonlinearity coefficient β and the transformed Reynolds number (Re*pl) can be deduced from Eq. (19). Figure 3 illustrates that as the Reynolds number escalates, β experiences an initial growth before it diminishes. Concurrently, a spike in the rheological index results in a temporary increase, then a decrease in the peak value of β. Notably, the Reynolds number corresponding to this peak value progressively augments.

Fluid-solid coupling method for fracture-slurries

Establishment of a fluid-solid coupling method for fracture-slurries

Grouting slurries can be viewed as power-law fluids at water-cement ratios below 0.7. In “Forchheimer’s formula for fracture slurries” of the article, we derive the Forchheimer’s formula applicable to power-law fluids. According to the formula derivation process, the relevant parameters of grouting slurry are mainly consistency coefficient K, rheological index n and density ρ, which are represented in Eq. (12) and Eq. (13).

Taking into account that the slurry flow within the fractures will invariably influence the fractures themselves, this study posits a direct linear correlation between the fracture aperture and the slurry pressure. The connection between the fracture aperture and the slurry pressure is characterized by the normal elastic coefficient, whose value is dictated by the range of grouting influence and the elastic modulus of the rock mass on both sides of the fracture. The governing equation for the deformation of the fracture61 can be articulated as follows:

Where, b represents the opening width of the fracture after it opens, m; b0 represents the initial opening width of the fracture, m; P represents the pressure exerted on the inner wall of the fracture, in megapascals, MPa; Pc is the pressure at the beginning of the opening of the fracture, MPa; kn represents the stiffness coefficient of the surrounding rock of the fracture, in meters per gigapascal, m/GPa; kn=D/E, where D represents the hydraulic diameter of the fracture, m; and E represents the elastic modulus of the rock, GPa.

Upon deriving the aforementioned fracture control equation, we employ a specific algorithm in conjunction with the fluid equation acquired from the preceding chapter for an improved prediction of the fracture-slurry model. Detailed calculation steps are outlined below:

-

(1)

Establish computation parameters: Parameters to be set include grouting parameters such as total grouting time (t), total grouting pressure (P); fracture properties like the initial fracture aperture (b); and rheological parameters of the slurry such as consistency coefficient (K) and rheological index (n).

-

(2)

Parameter discretization: As depicted in Fig. 4, the total computation time t is discretized. Within each time interval Δt, the distance of slurry flow is labelled li (i = 1, 2, 3, ···, n), with the total slurry flow distance over time t being \(L = \sum_{i = 1}^n {l_i }\). Assuming that the aperture of each fracture stays constant within each Δt interval, denoted as bi, the pressures at both ends are Pi and Pi+1, respectively.

-

(3)

Parameter Initialization: By applying Darcy’s law without considering the fluid-solid coupling, the initial values of the parameters for iterative calculation are set. Specifically, the pressure is set to linearly decrease as \(P_i = \frac{n - i + 1}{n}P\)(i = 1, 2, 3, …, n, n + 1), and the average flow velocity is set as \(v_i = - k\frac{{P_{i + 1} - P_i }}{{\mu_{pl} l_i }}\), where \(k = \frac{b^2 }{{12}}\). Then, by using \(v_i = \frac{dl_i }{{d\Delta t}}\)62 we obtain \(l_i = \sqrt {{ - \frac{{P_{i + 1} - P_i }}{{6\mu_{pl} }}b^2 \Delta t}}\).

-

(4)

Linear Iteration: Upon initializing parameters, the primary step involves an iterative calculation of the grouting pressure, underpinned by the law of mass conservation and the fracture deformation control equation. Throughout this iterative process, there is a concurrent correction of the fracture aperture, average flow velocity, and flow distance for each time interval.

Based on the law of mass conservation, when substituting “\(v_i b_i = v_{i + 1} b_{i + 1}\)” into the equation for average flow velocity, we can obtain the result.

$$P_i = \frac{{P_{i - 1} \frac{{b_{i - 1}^3 }}{{l_{i - 1} }} + P_{i + 1} \frac{b_i^3 }{{l_i }}}}{{\frac{{b_{i - 1}^3 }}{{l_{i - 1} }} + \frac{b_i^3 }{{l_i }}}}\quad (i=2,2,3,\ldots,n)$$(26) -

(5)

Nonlinear Parameter Calculation: Utilizing the results obtained from linear iteration as initial values, we proceed with the determination and computation of pertinent parameters relevant to the Forchheimer flow of fractured slurry (also known as power-law slurry). The parameters under consideration include the calculation of the shape factor \(v_i b_i = v_{i + 1} b_{i + 1}\), relative Reynolds number Re*pl, along-flow resistance coefficient λ, and the nonlinear coefficient β.

-

(6)

Nonlinear Iteration: In a similar vein, the iterative calculation of grouting pressure is conducted according to both the principle of mass conservation and the fracture deformation control equation. Throughout this iterative process, factors such as the fracture aperture, average flow velocity, flow distance within each discrete time interval, along with the nonlinear coefficient β, are concurrently adjusted.

By substituting \(v_i b_i = v_{i + 1} b_{i + 1}\) into Eq. (17) and processing it, we can obtain the result.

$$P_i = \frac{{P_{i - 1} \frac{{b_{i - 1}^3 }}{{\lambda_{i - 1} l_{i - 1} }} + P_{i + 1} \frac{b_i^3 }{{\lambda_i l_i }}}}{{\frac{{b_{i - 1}^3 }}{{\lambda_{i - 1} l_{i - 1} }} + \frac{b_i^3 }{{\lambda_i l_i }}}}\quad (i = 2, 2, 3, \ldots, n)$$(27) -

(7)

Evaluating Calculation Errors: During the iterative calculation process, the necessity arises to validate if the iteration fulfills the stipulated requirements. This is achieved by calculating the relative error between identical iterative parameters over two consecutive iteration steps.

-

(8)

Output of Calculation Results: Upon the convergence of the calculation process and fulfillment of the error requirements in the calculation results, relevant flow parameters are outputted. These parameters comprise of pressure distribution within the fracture, coupled calculation-derived fracture aperture, non-linear coefficients, slurry flow distance, along with the distribution of average flow velocity, among others.

The calculation process is shown in Fig. 5.

Verification of the discrete model for fracture-fluid coupling

Upon the completion of the calculation program, numerical simulations were performed using COMSOL Multiphysics® software (version 6.2; https://www.comsol.com/) to validate the water flow and power-law fluids in fractures. Owing to substantial limitations in numerical computations, only Newtonian fluids can be represented as fluid parameters in the two-phase flow model and the computational expense for turbulent flow models is prohibitively high. Hence, to validate the water flow in fractures, a transient two-phase flow model driven by water is utilized. In corroborating the power-law fluids, a fracture of fixed length is created to verify the average flow velocity once the fluid reaches stability.

Initial and boundary conditions are assumed as follows: In the numerical simulation of COMSOL water-driven gas, the chosen physical fields are laminar flow and phase field, with laminar flow as a pressure boundary, inlet pressure 100 Pa and outlet 0 Pa, and the wall set as a no-slip boundary. The multiphysics field is set as a two-phase flow phase field, with fluid 1 set as air and fluid 2 as water in the phase field, and the contact angle is set as pi/2.

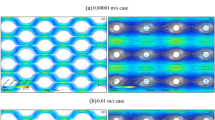

(1) Simulation of water driving gas two-phase flow.

A laminar flow model was utilized for calculations, establishing an injection pressure of 100 Pa, a fracture aperture of 1 mm, a fracture length of 0.5 m, and a segmented simulation time: 0.1–1 s and 3–15 s. Simulating water flooding with gas using the transient two-phase flow model: The “laminar flow” module and the “phase field” module are selected. The grid is a structured quadrilateral grid, with the maximum element size of 0.117 mm and the minimum element size of 0.0335 mm. The boundary layer grid has 8 layers, and the stretching factor is 1.2. The initial step size Δt is 0.1s, and the maximum step size is 1s. The relative error of pressure or velocity change between two consecutive iterations is less than 5e-3, and the maximum number of iterations is 100.

The comparison results (see Fig. 6) demonstrate a robust consistency between the model’s calculated outcomes and the numerical simulation findings during both the initial stage of 0.1–1 s and the stable stage of 3–15 s. Throughout the entire simulation period, the average relative error of the two was less than 2.5%.

(2) Simulation of Turbulent Flow of Power-Law Fluid in Fractures.

A comparative verification of the power-law fluid flow is conducted in COMSOL using the parameters listed in Table 1. Here, we temporarily disregard the fluid-solid coupling (Pc<P). It is assumed that the far end of the fracture extends to infinity and experiences zero pressure. The fractures are filled with air. The wall function is set by default, and the Reynolds number of the model is about 4.4e3 according to Eqs. (13) and (22). The Reynolds number in the flow process is 9e4 ~ 4.4e3 (the fracture mesh size is 0.1 m). Select the “Turbulence, k-ε” module. The grid adopts a structured quadrilateral grid, with the maximum element size of 0.124 mm and the minimum element size of 0.013 mm. The boundary layer grid has 10 layers, and the stretching factor is 1.2. The initial step size Δt is 0.1s, and the maximum step size is 1s. The relative error of pressure or velocity change between two consecutive iterations is less than 5e-3, and the maximum number of iterations is 100.

The software adopts the k-ε model, and the velocity distribution at the outlet of the fracture is calculated after 500s (to ensure reaching a steady flow state), as shown in Fig. 7.

Subsequent to the numerical computations, the mean flow velocity within the fracture was ascertained to be 3.66 m/s. Utilizing the model program elaborated upon within this paper, it was projected that approximately 11 s were required for fluid to traverse a distance of 60 m. This corresponded to an average flow velocity of 3.70 mm/s at that juncture. The deviation between the two is only 1.1%. Figure 8 illustrates the interrelation amongst time, flow distance, and flow velocity during the fluid’s transit process.

Numerical validation demonstrates a significant consistency with the numerical results for both laminar water flow and turbulent power-law fluid flow. This consistency affirms the accuracy of the discrete fracture-fluid model, proposed within this study, for power-law fluids. Furthermore, when this model is used to detect the slurry within the crack network, the computing time is only 1/10 to 1/100 of that of the numerical method. Therefore, it ensures high computational accuracy while reducing the computing time. Subsequently, the influence of fluid-solid coupling, as well as fluid parameters, are precisely examined through calculations derived from distinct cases.

Model analysis and application

Comparison of different flow models

Comparisons of flow models in varying states have been conducted utilizing an established model. For these comparisons, water was the fluid of choice while fluid-solid coupling was intentionally disregarded for the time being. Pertinent parameters are documented in Table 2.

It is commonly acknowledged that pressure in grouting endeavors often surpasses laboratory experiment levels, particularly in ground pre-grouting projects where grouting pressure frequently exceeds 10 MPa63. In the context of fractured grouting initiatives within wells of kilometer-depth, the peak grouting pressure can approach almost 30 MPa64. At such junctures, when the slurry’s flow distance falls short due to significant pressure gradients, the flow state will invariably deviate from the laminar. As a consequence, a grouting pressure of 10 MPa is assumed for this study. The correlation between the fluid flow distance and time is computed under the conditions of cubic law, unsteady cubic law, and Forchheimer law.

From the computational outcomes presented in Fig. 9, it is noticeable that within a logarithmic coordinate system and conforming to cubic law, there exists a linear correlation between the flow distance and flow time when the flow operates under constant pressure. During the early stages of flow, the unsteady cubic law reveals substantial deviation from the steady laminar model. However, after a brief duration of merely 0.3 s under these flow parameters, it essentially aligns with the results derived from the cubic law model.

A significant discrepancy is observed when comparing the results obtained from the application of the Forchheimer law to those of the cubic law, particularly during the initial phase of turbulence. Even at the culmination of this turbulent phase, the flow distance within an identical time span diverges by approximately 50% in comparison to the cubic law. Upon transitioning into the laminar phase, the nonlinear coefficient β approximates zero. Due to the fact that the flow distance at this juncture is lesser than that calculated by the cubic law, it leads to an enhanced pressure gradient and increased flow velocity. Consequently, as time progresses, the flow distance gradually converges towards the predictions made by the cubic law.

Influence of fluid parameters

The comparative analysis elucidates a substantial degree of error inherent in the prevalent calculation model reliant on cubic law in grouting engineering. As a corrective measure, this paper proposes a Forchheimer law-based model, centered around power-law slurry, to facilitate more precise computation of the slurry flow characteristics in a singular fracture. The effects of varying slurry parameters such as the consistency coefficient and rheological index on slurry flow velocity were examined through computational comparison. This study was conducted under conditions of a grouting pressure of 10 MPa and a fracture aperture of 1 mm.

Calculations indicate that under turbulent state, the overall distance of power-law slurry flow undergoes significant reduction with the escalation of the consistency coefficient (refer to Fig. 10). For slurry with a consistency coefficient (K) of 0.001 Pa·sn, the initial flow distance possesses greater resemblance to that of the slurry with K = 0.01 Pa·sn. This is primarily due to the high-impact energy loss induced by the flow state at this phase, which surpasses the impact of the consistency coefficient. Despite the difference in K values, their relative contributions to total resistance are overshadowed by the dominant inertial dissipation during the initial turbulent stage. This results in minimal disparity in the calculated initial flow distance. In other words, within this high-impact regime, the energy dissipation mechanism becomes the primary factor governing flow distance.

The rheological index also exerts a noteworthy influence. For a consistent consistency coefficient (K = 0.01 Pa·sn), a smaller rheological index (see Fig. 11) corresponds to a reduced apparent viscosity of the slurry during its flow, resulting in lower resistance, thereby accelerating the flow velocity. Accordingly, under the same time duration, the slurry achieves greater flow distance.

Effects of fluid-solid coupling

Upon incorporating the fluid-solid coupling into consideration, parameters for the model are set as follows: the fracture initiation pressure (Pc) is fixed at 5 MPa, the influence range (D) is determined as 1 m, and the elastic modulus (E) is set at 6 GPa. Subsequently, utilizing the parameters associated with water, the equivalent flow distance of water is computed for the same duration. In order to facilitate comparative analysis, four distinct cases are established:

Case 1

Application of the laminar flow model, excluding the consideration of fluid-solid coupling.

Case 2

Application of the laminar flow model, inclusive of the fluid-solid coupling.

Case 3

Adoption of the turbulent flow model, disregarding the fluid-solid coupling.

Case 4

Adoption of the turbulent flow model, inclusive of the fluid-solid coupling.

Considering a power-law fluid with K = 0.01 Pa·sn, n = 0.8, ρ = 1400 kg/m3, the pressure and aperture distribution inside the fracture at 1s are calculated using both turbulent flow and turbulent flow and fluid-solid coupling model, as shown in Fig. 13. The observation indicates that the expansion of the aperture within a certain threshold has a relatively minor influence on the flow distance calculated by the turbulent flow model for power-law fluids.

Figure 12 depicts the pressure and aperture distribution under various circumstances at 1 s. A noticeable observation is that the flow distance of water within the fracture follows a decreasing order, ranking from case 2, then case 1, followed by case 4, and finally case 3. In cases 2 and 4, variations in fracture apertures lead to a nonlinear distribution of pressure along the trajectory until the aperture reverts to its original value. Given the fluid-structure interaction, an enlargement in fracture aperture results in an extended fluid flow distance. Within turbulent flow models, an elevation in flow velocity induces increased flow resistance. Thus, the impact of fluid-structure interaction stands out more prominently in laminar flow models.

Engineering applications

Project overview

Qinan Coal Mine is located in Suzhou City, Anhui Province, “7244” working face is the second section of “72” coal seam in the right flank of 84 mining area, the upper part is “7242” working face; the lower part is “7246” working face, the left side is bounded by the protection coal pillar of the upper hill of the mining area body, and the right side is bounded by the boundary of 84 mining area. The design of the working face of “7244” has the length of strike of 584~623 m, the average is 603.5 m, the inclined width is 217 m, the inclined area is 130959.5 m2is a comprehensive mining face. Figure 14 show the plan view of “7244” working face and the comprehensive stratigraphic histogram.

The surrounding rock of “7244” working face has low strength and fissure development, and the anchoring condition is poor. Under the action of multiple stress disturbance, anchorage failure is very easy to occur, as shown in Fig. 15. Based on the analysis of the geological data of the treatment area, it is decided to adopt the ground pre-injection grouting technology to transform the target area. On the one hand, this technology can reinforce the fault broken area; on the other hand, the injected slurry can effectively replace the water in the fissure rock body, and at the same time cement the fissure rock body as a whole, so as to transform the aquifer into a water barrier layer, increase the thickness of the water barrier layer, and effectively prevent the sudden water accident in the process of subsequent roadway excavation.

Calculation of the seepage distance of the slurry in the fissure

When slurry seeps through a fractured rock body, its seepage pattern does not show a columnar or spherical spread. Since the slurry will preferentially flow into wider fissure channels, its actual morphology is extremely irregular. For this reason, in this section, based on the non-Darcy seepage model of slurry in a single fissure, the change of slurry seepage distance with time is calculated to study the furthest seepage distance of slurry in the surface pregrouting project.

According to the geological data of the Qinan coal mine management area, the average fissure opening of the core obtained from drilling near the fault is about 1.2 mm statistically, the grouting pressure is set to 10 MPa, 12 MPa, 14 MPa, 16 MPa, 18 MPa and 20 MPa, and the rheological parameters of the cement slurry used are shown Table 3, and the calculation results are shown in Fig. 16.

Calculation results show that the seepage distance of the slurry at the same time increases gradually with the increase of grouting pressure. When the grouting pressure is 10 MPa, the seepage distance of the slurry in 20 min is 409 m. When the grouting pressure increases to 20 MPa, the seepage distance in 20 min reaches 557 m, which is an increase of about 36%. Figure 16 shows that when the injection pressure is 16 MPa, the seepage distance of the slurry reaches 508 m. With the further increase of injection pressure, the growth rate of seepage distance decreases significantly. This phenomenon comes from the increasing resistance of the slurry due to the expansion of the seepage range. Therefore, for the geological characteristics of Qinan coal mine, the comprehensive analysis shows that the slurry injection pressure should be selected at about 18 MPa, and the seepage range of the slurry at this time is 532 m.

Analysis of the effect of ground pregrouting in fractured rock bodies in fault fracture zones

(1) Grouting volume analysis.

Qinan Coal Mine set up a main borehole and 6 sub-boreholes, the total grouting volume is 12,057 t of cement, and the grouting volume of each sub-borehole is shown in Table 4. After the injection of sufficient amount of slurry, it not only replaces the water in the fissured rock body, but also makes the fissured rock body cemented into a whole, and transforms the water-bearing layer into a water-insulating layer, which increases the thickness of the water-insulating layer effectively.

(2) Grouting diffusion distance analysis.

In order to measure the range of slurry diffusion, a number of peepholes were deployed around the grouting holes, and their positions were arranged in a spiral pattern. Based on the observation results from each viewing hole, the positions of the subsequent viewing holes will be dynamically adjusted, as shown in Fig. 17. Combined with the peephole results, cement exposure from downhole excavation, and information on slurry running in the downhole roadway, it can be seen that the seepage distance of the slurry along the fault in this grouting project is up to 496 m, which is closer to the 532 m predicted under the aforementioned 18 MPa grouting pressure condition, with an error of 7.26%. Through the implementation of segmental grouting, isolation grouting and repetitive grouting, it effectively ensures the reinforcement effect of the surrounding rock in the fault fracture zone.

Conclusion

Addressing the prediction challenges of nonlinear flow for power-law grouts in high-pressure fractured rock grouting, this study extended the Forchheimer formula to fracture flow, proposing a suitable nonlinear Forchheimer flow model. Pore and fracture flow were unified through a shape factor. Furthermore, by incorporating the slurry pressure-fracture deformation constitutive relationship, a novel fluid-solid coupling model for grout in fractures was developed, providing a theoretical tool for optimizing grouting parameters. The key findings are as follows:

-

(1)

This study derives a conversion method for calculating the mean flow velocity in pipes with circular and rectangular cross-sections. When the aspect ratio (width to opening ratio) of the fracture exceeds 30:1, the calculation results obtained using the shape factor exhibit an error of 4.53%. It can be inferred that flow in rectangular cross-section pipes with an aspect ratio exceeding 30:1 can be approximated as parallel-plate fracture flow. This provides a laboratory standard for accurately replicating fracture flow using rectangular models.

-

(2)

A Forchheimer equation suitable for power-law fluids is derived. The results indicate that the nonlinear coefficient β initially increases and subsequently decreases with increasing Reynolds number (Re). When the Reynolds number falls within the range of 1500–30,000, β reaches its peak value, ranging from 0.01 to 0.013, before gradually decreasing. Further analysis reveals that the peak value of β initially increases with the rheological index until the index reaches 1.2, after which it begins to weaken. Moreover, the Reynolds number corresponding to the peak value of β increases linearly with the rheological index.

-

(3)

The model calculation results exhibit a high degree of consistency with COMSOL numerical simulations. The average relative error between the calculation results of the water-gas two-phase flow model and the numerical simulation results is less than 2.5%, and the deviation for power-law turbulent flow velocity is only 1.1%. Furthermore, when this method is used to detect slurry flow within a fracture network, the computational efficiency is significantly superior to numerical methods, with computation time being only 1/10 to 1/100 of that required by numerical methods. Therefore, it ensures high computational accuracy while substantially reducing computation time. Additionally, field application data indicate a prediction error of 7.26% for slurry diffusion distance.

-

(4)

By integrating Forchheimer’s law for power-law fluid flow within fractures, a simplified and practicable method for fluid-solid coupling is formulated by discretizing the fractures. Simulations carried out under stipulated conditions indicate that accounting for fluid-solid coupling results in a nonlinear pressure distribution in the fractures as the fracture aperture expands. This also causes an upsurge in fluid flow distance. Yet, in the turbulence model, higher flow velocity brings about elevated flow resistance, thus minimizing the effect of fluid-solid coupling. Future research will focus on tracking the dynamic evolution of the Reynolds number during the grouting process and delving deeper into its real-time coupling characteristics with fracture deformation and variations in slurry rheological parameters.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Cheng, W., Liu, Z., Yang, H. & Wang, W. Non-linear seepage characteristics and influential factors of water injection in gassy seams. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 91, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2017.10.002 (2018).

Weiyao, Z. et al. Unstable seepage modeling and pressure propagation of shale gas reservoirs. Petroleum Explor. Dev. 43, 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1876-3804(16)30032-5 (2016).

Mięsiak-Wójcik, K., Turczyński, M. & Sposób, J. Diverse sediment permeability and implications for groundwater exchange in closed Lake-Wetland catchments (West polesie, East Poland). Wetlands 38, 779–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1027-4 (2018).

Bayer-Raich, M. et al. Estimates of horizontal groundwater flow velocities in boreholes. Groundwater 57, 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12820 (2019).

Li, H. Research on seepage properties and pore structure of the roof and floor strata in confined Water-Rich coal seams: taking the Xiaojihan coal mine as an example. Adv. Civ. Eng. 9483637 https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9483637 (2018). (2018).

Yin, L., Shi, N. & Chen, J. Research of mining depth influence on floor coupled. Taishan Acad. Forum–Project Mine Disaster Prev. Control. 224–230. https://doi.org/10.2991/mining-14.2014.35 (2014).

Sarkhosh, P., Samani, J. M. V. & Mazaheri, M. A one-dimensional flood routing model for rockfill dams considering exit height. Proc. Inst. Civil Engineers-Water Manage. 171, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1680/jwama.16.00015 (2018).

Wang, J., Liu, H., Zhang, J. & Xie, J. Lost gas mechanism and quantitative characterization during injection and production of water-flooded sandstone underground gas storage. Energies 11, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11020272 (2018).

Isa, Z., Fulford, G., Kelson, N. & Farrell, T. Flow field and traverse times for fan forced injection of fumigant via circular or annular Inlet into stored grain. Appl. Math. Model. 40, 7156–7163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2016.03.008 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. COD (glucose configuration) effects on the non-Darcy flow of compacted clay in a municipal solid waste landfill. Waste Manage. 84, 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.12.004 (2019).

Dukhan, N. Analysis of Brinkman-extended Darcy flow in porous media and experimental verification using metal foam. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4005678

Shahrad, K. B. & Farhad, E. M. Enhanced oil recovery with air injection: effect of the temperature variation with time. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b02661

Wang, Y., Wang, X. H. & Chen, J. R. Research on effect of grouting circle on seepage field of subsea tunnel. Appl. Mech. Mater. 204, 1409–1412. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.204-208.1409 (2012).

Angelini, O., Chavant, C., Chénier, E., Eymard, R. & Granet, S. Finite volume approximation of a diffusion–dissolution model and application to nuclear waste storage. Math. Comput. Simul. 81, 2001–2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2010.12.016 (2011).

Hubbert, M. K. Darcy’s law and the field equations of the flow of underground fluids. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2, 23–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626665709493062 (1957).

Nchabeleng, M. & Fareo, A. Group invariant solution for a fluid-driven fracture with a non-Darcy flow in porous medium. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 115, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2019.04.006 (2019).

Nikitin, K. D. & Yanbarisov, R. M. Monotone embedded discrete fractures method for flows in porous media. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 364, 112353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cam.2019.112353 (2020).

Hosseinejad, F., Kalateh, F. & Mojtahedi, A. Numerical investigation of liquefaction in Earth dams: a comparison of Darcy and non-Darcy flow models. Comput. Geotech. 116, 103182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.103182 (2019).

Li, Z., Tang, T., Liu, Y., Arcondoulis, E. J. & Yang, Y. Implementation of compressible porous-fluid coupling method in an aerodynamics and aeroacoustics code–Part II: turbulent flow. Appl. Math. Comput. 373, 124988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2019.124682 (2020).

Forchheimer, P. Wasserbewegung durch Boden, Zeitschrift des Vereines Deutscher Ingenieuer. (1901).

Zimmerman, R. W., Al-Yaarubi, A., Pain, C. C. & Grattoni, C. A. Non-linear regimes of fluid flow in rock fractures. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2004.03.036 (2004).

Bear, J. Dynamics of fluids in porous media. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7061(75)90077-4

Zeng, Z. & Grigg, R. A criterion for non-Darcy flow in porous media. Transp. Porous Media. 63, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-005-2720-3 (2006).

Sidiropoulou, M. G., Moutsopoulos, K. N. & Tsihrintzis, V. A. Determination of Forchheimer equation coefficients a and b. Hydrol. Processes: Int. J. 21, 534–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.6264 (2007).

Moutsopoulos, K. N., Papaspyros, I. N. & Tsihrintzis, V. A. Experimental investigation of inertial flow processes in porous media. J. Hydrol. 374, 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.06.015 (2009).

Zimmerman, R. W. & Bodvarsson, G. S. Hydraulic conductivity of rock fractures. Transp. Porous Media. 23, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.2172/60784 (1996).

Javadi, M., Sharifzadeh, M., Shahriar, K. & Mitani, Y. Critical Reynolds number for nonlinear flow through rough-walled fractures: the role of shear processes. Water Resour. Res. 50, 1789–1804. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014610 (2014).

Zou, L., Jing, L. & Cvetkovic, V. Roughness decomposition and nonlinear fluid flow in a single rock fracture. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 75, 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2015.01.016 (2015).

Zami-Pierre, F., de Loubens, R., Quintard, M. & Davit, Y. Effect of disorder in the pore-scale structure on the flow of shear-thinning fluids through porous media. J. Non-Newton Fluid Mech. 261, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2018.08.004 (2018).

Qian, J., Zhan, H., Luo, S. & Zhao, W. Experimental evidence of scale-dependent hydraulic conductivity for fully developed turbulent flow in a single fracture. J. Hydrol. 339, 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.03.015 (2007).

Zhang, Z., Nemcik, J. & Ma, S. Micro-and macro-behaviour of fluid flow through rock fractures: an experimental study. Hydrogeol. J. 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-013-1033-9 (2013).

Mullin, T. Experimental studies of transition to turbulence in a pipe. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 43, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-122109-160652 (2011).

Reynolds, O. X. X. I. X. An experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B-Biol Sci. 935–982. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1883.0029 (1883).

Shombert, G. D. Measurement of turbulent flow in vascular grafts. Proc. Fifteenth Annual Northeast Bioeng. Conf. 85–86. https://doi.org/10.1109/nebc.1989.36710 (1989).

Tam, L. M. & Ghajar, A. J. Transitional heat transfer in plain horizontal tubes. Heat. Transf. Eng. 27, 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01457630600559538 (2006).

Everts, M. Single-phase Mixed Convection of Developing and Fully Developed Flow in Smooth Horizontal Tubes in the Laminar, Transitional, quasi-turbulent and Turbulent Flow Regimes (University of Pretoria (South Africa), 2017).

Garagash, D. Transient solution for a plane-strain fracture driven by a shear‐thinning, power‐law fluid. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 30, 1439–1475. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.535 (2006).

Zia, H. & Lecampion, B. Propagation of a height contained hydraulic fracture in turbulent flow regimes. Int. J. Solids Struct. 110, 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2016.12.029 (2017).

Gee, B. & Gracie, R. Beyond poiseuille flow: a transient energy-conserving model for flow through fractures of varying aperture. Adv. Water Resour. 164, 104192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104192 (2022).

Zou, L., Håkansson, U. & Cvetkovic, V. Radial propagation of yield-power-law Grouts into water-saturated homogeneous fractures. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 130, 104308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104308 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. Experimental investigation of Grout nonlinear flow behavior through rough fractures. Processes 7, 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7100736 (2019).

Liu, R., Yu, L. & Jiang, Y. Quantitative estimates of normalized transmissivity and the onset of nonlinear fluid flow through rough rock fractures. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 50, 1063–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1147-1 (2017).

Ding, W., Lei, B., Duan, C. & Zhang, Q. Grout diffusion model for single fractures in rock considering influences of grouting pressure and filling rate. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 158, 106392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106392 (2025).

Ewis, K. M. & Allah Soliman, H. A. More accurate solution of mixed convection radiative power law fluid flow over a stretching porous surface with presence of Forchheimer and chemical reaction. Numer. Heat. Transf. Part. A. 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10407782.2024.2357589 (2024).

Bibby, R. Mass transport of solutes in dual-porosity media. Water Resour. Res. 17, 1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1029/wr017i004p01075 (1981).

Miao, T., Yang, S., Long, Z. & Yu, B. Fractal analysis of permeability of dual-porosity media embedded with random fractures. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 88, 814–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2015.05.004 (2015).

Hart, J., Hamersma, P. & Fortuin, J. Correlations predicting frictional pressure drop and liquid holdup during horizontal gas-liquid pipe flow with a small liquid holdup. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 15, 947–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9322(89)90023-2 (1989).

Neuman, S. P. Theoretical derivation of darcy’s law. Acta Mech. 25, 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01376989 (1977).

Sutera, S. P. & Skalak, R. The history of poiseuille’s law. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 25, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fl.25.010193.000245 (1993).

Liu, J. et al. Determination of full-scale pore size distribution of Gaomiaozi bentonite and its permeability prediction. J. ROCK. MECH. GEOTECH. 12, 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2019.12.005 (2020).

Blasius, H. In Mitteilungen Über Forschungsarbeiten Auf Dem Gebiete Des Ingenieurwesens: Insbesondere Aus Den Laboratorien Der Technischen Hochschulen1–41 (Springer, 1913).

Cornish, R. J. Flow in a pipe of rectangular cross-section. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 120, 691–700. (1928). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1928.0175

JonesJr O. An improvement in the calculation of turbulent friction in rectangular ducts. (1976).

Ruth, D. & Ma, H. On the derivation of the Forchheimer equation by means of the averaging theorem. Transp. Porous Media. 7, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01063962 (1992).

Skjetne, E., Hansen, A. & Gudmundsson, J. High-velocity flow in a rough fracture. J. Fluid Mech. 383, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022112098002444 (1999).

Ranjith, P. & Viete, D. Applicability of the ‘cubic law’for non-Darcian fracture flow. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 78, 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2011.07.015 (2011).

Liu, Q., Lei, G., Peng, X., Lu, C. & Wei, L. Rheological characteristics of cement Grout and its effect on mechanical properties of a rock fracture. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 51, 613–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1340-x (2018).

Metzner, A. & Reed, J. Flow of non-newtonian fluids—correlation of the laminar, transition, and turbulent‐flow regions. AICHE J. 1, 434–440. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690010409 (1955).

Bird, R. B. Transport phenomena. Appl. Mech. Rev. 55, R1–R4. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2509(61)85040-9 (2002).

Dodge, D. & Metzner, A. Turbulent flow of non-Newtonian systems. AICHE J. 5, 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690050214 (1959).

Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Liu, R. & Li, S. Grouting mechanism in fractured rock considering slurry-rock stress coupling effects. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 40, 2003–2011. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE201811006 (2018).

Ren, B. et al. Unsteady approximate model of grouting in fractured channels based on Bingham fluid. Geofluids 2021 (6671982). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6671982 (2021).

Qian, D. et al. Application and evaluation of ground surface pre-grouting reinforcement for 800-m-deep underground opening through large fault zones. Arab. J. Geosci. 10, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-017-3052-7 (2017).

ZHANG, Z. et al. Study and application of high-pressure splitting grouting modification technology in coalmine with depth more than 1000 m. J. China Coal Soc. 45 https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.SJ19.1545 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (Grant Numbers 242102320187).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kai Wang:Methodology, conceptualization, resources, writing—review & editing,supervision. Pengyu Chen: methodology, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, roles/writing—original draft. Kejian Xu: data curation, investigation. Chaojie Yang: formal analysis, investigation. Yifan Li: validation, investigation. Huining Zong: formal analysis, investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Chen, P., Xu, K. et al. A forchheimer-based fluid-solid coupling model for nonlinear flow of power-law grouts in fractured rock grouting. Sci Rep 15, 29445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15441-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15441-7