Abstract

The French Poison Centers database is a tool of choice for the analysis of poisoning cases requiring the administration of an antidote although not all uses are systematically reported. This national retrospective study aims to report trends of use of antidotes in France over a 7-year period from 2015 to 2021. A total of 25,289 cases of poisoning required the administration of an antidote, among which 46.7% were moderate to severe. While 77.1% of poisonings progressed toward recovery, the observed mortality rate was 1.7%. The 3 most frequently used antidotes according to data from Poison Centers were N-acetylcysteine (n = 13,555 [53.6%]), flumazenil (n = 3102 [12.3%]) and naloxone (n = 1740 [6.9%]) reflecting the most common types of poisoning involving acetaminophen, benzodiazepines, and opioids. The observed use of methylthioninium chloride, hydroxocobalamin, cyanocobalamin and DOAC reversal agents increased, both in terms of absolute numbers and proportions, revealing new behaviors leading to poisoning, such as nitrous oxide consumption. Conversely, the observed use of ethanol-based therapy, L-carnitine, and dantrolene decreased over time, reflecting both current medical practices and shifts in guidelines. This study provides a novel insight into the typology (circumstances, severity, development) of poisonings requiring an antidote, as well as the description of the causative agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poisoning remains a major global health issue, affecting millions each year. The xenobiotics involved in poisoning, as well as the circumstances under which poisoning occurs, are diverse. Xenobiotics—including pharmaceuticals, pesticides, industrial chemicals, and natural toxins from plants, fungi, and animals—can cause severe physiological complications, potentially leading to irreversible damage or death if not managed promptly and effectively1,2. The management of poisoning requires a multifaceted approach, including supportive care, decontamination, and, when appropriate, the use of antidotes3.

Antidotes are specific pharmacological agents that neutralize or counteract the harmful effects of xenobiotics. They act through various mechanisms, such as neutralizing the xenobiotic, inhibiting its absorption, accelerating its elimination, or reversing its physiological effects. Several factors contribute to limiting the use of antidotes. The first, and most obvious, is that there are many xenobiotics for which no antidote is available. The second is that for some antidotes, the administration of which is sometimes based on pathophysiological factors, scientific evidence proving they modify patient prognosis is lacking. The third is that the use of antidotes often requires precise knowledge of the toxicological profile of the involved agent and the clinical condition of the patient4. Finally, even when proven to be effective, their use is often limited by their availability, which may be constrained by storage conditions (often restricted to hospital use or administered upon the recommendation of a Poison Center) or by regulations in the country5,6,7,8. Consistently, antidotes which represent a highly heterogeneous class of drugs, in terms of recommendation and frequency of use, geographical distribution and cost clinicians’ knowledge and practices vary widely, which can lead to sub-optimal use of these drugs (misuse, delayed treatment)9.

Limited data is available on the national use of antidotes9,10. This study aims to describe trends in antidote use in France from 2015 to 2021, based on an analysis of the French National Poisoning Database maintained by the French PCs.

Methods

Data source

In France, eight PCCs operate a 24/7 phoneline, responding to all calls from the public and healthcare professionals regarding any type of toxic exposure. These calls are not mandatory in cases of exposure or poisoning and are left to the discretion of individuals. For each case, information is collected about the patient’s characteristics, exposure circumstances, the toxic agents involved, and the treatment recommended and carried out. Data are then stored anonymously in the French National Database of Poisonings (FNDP). The FNDP is administered by the French Ministry of Health.

Case selection

We first extracted all cases mentioning the use of an antidote (recommended or administered) from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2021, based on treatments categorized as antidotes in our database. The Supplementary Table 1 presents the pre-set list of antidotes in the database. Certain therapies were then redefined as emergency treatments rather than antidotes (oxygen therapy, diazepam, atropine, anticholinergic antiparkinsonian) and the corresponding cases were excluded, as were certain extremely specific treatments (iodine, Prussian blue, potassium iodide) (a). We have also excluded cases corresponding to administrations of sodium polystyrene sulfonate, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), other antibodies and chelators (a). Furthermore, cases for which the administration of an antidote was not documented were not included in the analysis (b). Antidotes with less than 10 reported uses over the study period were excluded (botulinum antitoxin, cyproheptadine, dexrazoxane, lipidic emulsion, nitrite, riboflavin, sodium salts, sodium thiosulfate, uridine triacetate) (c). Exclusion was carried out by filtering therapies according to criteria (a, b, c). Thus, cases relating to the use of the following antidotes were eligible for selection: N-acetylcysteine (NAC), flumazenil, naloxone, antivenoms, phytomenadione (vitamin K), glucagon, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), fomepizole (4-methylpyrazole), digoxin-specific antibodies, silymarin, high-dose insulin therapy, ethanol-based therapy, methylthioninium chloride, hydroxocobalamin, L-carnitine, folic acid (B9), dantrolene, calcium gluconate (topic), calcium salts, pralidoxime, octreotide, cyanocobalamin (B12), physostigmine, deferoxamine, protamine and reversal agents for DOACs11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

Data collection

For each case, we extracted the following information: patient characteristics (sex and age), causative agents, circumstances of poisoning, severity, and outcome. Circumstances defined as unintentional include circumstances referred to as accidental, therapeutic error/accident, depackaging, housework/gardening, fire, dietary, indoor air pollution, and siphoning. The circumstances defined as intentional include the following categories: suicide attempt, non-suicidal drug misuse or overuse, intentional other or undetermined, drug abuse/addiction, and criminal/malicious act. Poisoning severity was assessed using the Poisoning Severity Score (PSS) that includes five severity grades, i.e., 0 (no symptoms related to the poisoning), 1 (minor symptoms), 2 (moderate symptoms), 3 (severe symptoms) and 4 (fatal poisoning)37. Poisoning clinical outcome assessed as recovery, sequelae, death, or unknown when no follow-up was available.

Statistics

We presented quantitative variables as means ± standard deviations, and qualitative variables as numbers and percentages. If relevant, we compared variables using appropriate statistical tests: Student’s t-test or non-parametric Wilcoxon’s test for quantitative variables and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative ones. We performed statistical analysis using R Studio® 2023.06.0 + 421 for Windows® (R version 4.1.3) and using LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing) curves within the ggplot2 package. Bar plots and circular diagrams were performed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation (2019) Microsoft Excel (Version 18.08) for Windows®).

Ethics

The FNDP is registered and approved by the French Data Protection Authority (FDPA no 2020-131—Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés). The informed consent of patient’s personal data and its use for the purpose of research is waived in accordance with French law. The protocol was approved by the French PCC Research Group. All methods were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations as directed by FDPA. The research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

During the study period, 1,392,365 cases of exposure were recorded by French Poison Centers, or approximately 199,000 per year. Initially, 56,388 cases of poisoning mentioning the use of an antidote (recommended or administered) were extracted from the FNDP. After excluding (a, b, c), we included 25,289 cases (mean ± SD age: 35.0 ± 25.1 years; 59.6% were females) in the study, representing patients for whom a French PC was contacted and who received at least one antidote between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2021 (Fig. 1).

Over the 7-years study period, poisoning cases requiring antidote administration were intentional in more than three quarters of cases (77.0%) (Table 1). Poisoning severity was assessed as none in 16.8% of cases, minor in 35.1%, moderate in 27.1%, and severe in 19.6%. The overall mortality rate was 1.7% (n = 436).

Figure 2 presents for all antidotes used from 2015 to 2021, the poisoning circumstances, the implicated agents, as well as severity and outcomes.

Circumstances, implicated agents, severity and outcomes of poisonings requiring an antidote. The circumstances of poisoning are represented by stacked bar graphs, separating the types of unintentional circumstances from the intentional ones. The subdivisions represent the share (%) of each circumstance in each diagram. The agents involved and their frequencies are represented by pie charts. Severity and outcomes are represented by stacked bar charts. Severity is represented in red when high, orange when moderate, yellow when low, green when absent and gray when unknown. The outcome is represented in red when death, orange when sequelae, green when recovery and gray when unknown.

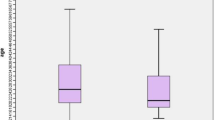

The Fig. 3 provides a descriptive summary of the data presented in (Fig. 2). For unintentional circumstances, the most common were accidental (mean = 45.4%) and therapeutic error/accident (mean = 35.1%). In contrast, indoor air pollution (mean = 0.3%) and practical work (mean = 0.1%) were rarely reported. Regarding intentional circumstances, suicide attempt was by far the most frequent (mean = 76.9%), while criminal/malicious act was rare (mean = 1.7%). The most commonly involved agents were drugs (mean = 47.4%), chemical products (mean = 13.1%), and other agents (mean = 15.3%). Less frequently reported were animals (mean = 3.8%), illicit drugs (mean = 2.8%), and plants (mean = 1.4%). In terms of severity, cases were most frequently classified as severe (mean = 31.5%) or moderate (mean = 30.6%). The absence of severity (none) was less common (mean = 12.9%). For outcomes, recovery was the most frequent conclusion (mean = 71.3%), followed by unknown outcomes (mean = 21.7%). Death and sequelae were rare, with means of 4.9 and 2.0%, respectively.

Eight antidotes were used more than 500 times during the study period, in descending order: N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (n = 13,555), flumazenil (n = 3,012), naloxone (n = 1,740), antivenoms (n = 1,131), phytomenadione (vitamin K) (n = 871), glucagon (n = 709), pyridoxine (vitamin B6) (n = 673), and fomepizole (n = 638) (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Tables 2–9). While the recorded proportion of NAC use increased from 48% in 2015 to 61% in 2021, the absolute number of uses remained relatively stable or slightly declined. This means that despite a relatively stable absolute number of cases requiring the administration of NAC, the proportion of this antidote out of the total number of administrations has increased over the period. In contrast, the use of other antidotes decreased both in absolute numbers and proportions over the same period. Fomepizole accounted for 2.6% of all antidote administrations recorded in 2015, falling to 1.8% in 2021. Over the period, the use of flumazenil fell from 14.8 to 9.2%, pyridoxin fell from 3.8 to 1.4%, phytomenadione from 5.4 to 2.2% and glucagon from 3.4 to 2.2%.

Eighteen antidotes were used less than 500 times during the study period: digoxin-specific antibodies (n = 454), silymarin (n = 327), high-dose insulin euglycemic therapy (n = 287), ethanol therapy (n = 272), methylthioninium chloride (n = 246), hydroxocobalamin (n = 243), L-carnitine (n = 223), folic acid (vitamin B9) (n = 222), dantrolene (n = 157), calcium gluconate (n = 93), calcium salts (n = 85), pralidoxime (n = 74), octreotide (n = 61), cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) (n = 54), physostigmine (n = 51), deferoxamine (n = 50), protamine (n = 33), and reversal agents for DOACs (n = 28) (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Tables 10–27). The observed use of methylthioninium chloride, hydroxocobalamin, cyanocobalamin and DOAC reversal agents increased, both in terms of absolute numbers and proportions. Conversely, the observed use of ethanol-based therapy, L-carnitine, and dantrolene decreased over time. Pralidoxime, octreotide, physostigmine, deferoxamine and protamine tended to decrease in both absolute numbers and proportions. For certain antidotes, such as silymarin and digoxin-specific antibodies, trends were more difficult to define due to significant year-to-year variations or a decline in absolute numbers despite an increase in proportional use. Among these antidotes, folic acid appeared to be the only one with stable use both in absolute numbers and proportion over time.

Of the 26 antidotes analyzed, they were used in both voluntary and involuntary circumstances. In fact, 13 antidotes were mainly used for deliberate poisonings (insulin, methylthioninium chloride, carnitine, calcium salts, pralidoxime, cyanocobalamin, physostigmine, octreotide, NAC, flumazenil, naloxone, phytomenadione, glucagon and pyridoxin) in relation with suicide attempts or addictive behavior. Interestingly, among the reported uses of flumazenil (n = 3012), 196 (6.5%) involved multiple intoxications with benzodiazepines and other proconvulsant drugs such as escitalopram (N = 76), amitriptyline (N = 59), fluoxetine (N = 51), clozapine (N = 8) and methylphenidate (N = 2).

Eleven antidotes were mainly indicated for unintentional poisoning (digoxin-specific antibodies, folic acid, silymarin, antivenom, hydroxocobalamin, protamine, reversal agent for DOAC, deferoxamine, calcium gluconate gel, dantrolene), involving exposure to natural toxins (fungi, snakes) or environmental phenomena (fires), but also exposure to drugs with narrow therapeutic index (digoxin or methotrexate). Fomepizole and ethanol, both indicated in the treatment of toxic alcohol poisoning, were used equally in cases of voluntary or involuntary poisoning.

Observed mortality rates above 5% concerned poisonings requiring the following antidotes: digoxin-specific antibodies (7.3%), insulin (7.7%), methylthioninium chloride (6.5%), hydroxocobalamin (21.5%), dantrolene (5.1%), calcium salts (11%), pralidoxime (10%), protamine (15%) and reversal agents for DOAC (14%).

For additional details, the complete dataset is available for each antidote in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Tables 2–27). A description of each tables is available in additional results.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide a comprehensive overview of antidote use in France from 2015 to 2021, based on data from the French National Database of Poisonings of French PCCs. Poisonings that required the use of an antidote were primarily intentional which is consistent with the relevant literature on this type of poisoning38,39,40. In almost 50% of cases poisonings requiring the administration of an antidote were moderate or severe, whereas previous studies usually reported poisonings of low or no severity40,41,42. The overall mortality rate was 1.7% over the study period but varied greatly according to the type of poisoning.

NAC, flumazenil, and naloxone were by far the most commonly represented antidotes in this study, which aligns with their status as the most frequently used antidotes11,43. However, the data presented are likely not exhaustive, as not all clinicians contact a PC before administering them. French PCs may play an important role in advising and training healthcare providers, even for common and well-known poisonings such as those involving paracetamol, benzodiazepines, and opioids. However, it is quite interesting to note that flumazenil was used in situations with risk of seizures in 196 of cases (6.5%) when multiple poisonings occurred with proconvulsant drugs.

Certain antidotes were used in a non-negligible proportion in the treatment of poisoning by natural toxins. Digoxin-specific antibodies were used in the treatment of plant poisonings, particularly oleander44,45. NAC was used in more than 400 cases of mushroom poisoning during the study period, often in combination with silymarin, which remains the only specific antidote for treating phalloidin syndrome to date20. Hydroxocobalamin was employed in some cases of bitter almond poisoning, known to contain cyanogenic compounds. Finally, poisonings by plants with anticholinergic properties were treated with physostigmine, particularly in certain cases of poisoning by datura and belladonna.

Phytopharmaceutical products remained a cause of severe poisonings, as evidenced by the number of vitamin K treatments administered to patients who had ingested rodenticides, often voluntarily. Although banned in the European Union, rare cases of poisoning by organophosphates—including malathion, dichlorvos, mevinphos, and chlorpyrifos – still persist.

Our data revealed a shift in the use of antidotes over time, in line with trends reported in the literature. For example, we observed a gradual replacement of ethanol by fomepizole in cases of toxic alcohol poisoning18. The use of fomepizole may further increase in the coming years due to its potential indication in severe paracetamol poisoning46. Regarding antidotes used in cardiotropic poisonings—such as glucagon, euglycemic insulin, and calcium salts—it is notable that glucagon continues to be widely used in the management of beta-blocker poisonings, and even in cases of calcium channel blocker poisonings, despite ongoing debate about its efficacy in these indications47. Euglycemic insulin-based treatment increased in the management of calcium channel blocker poisonings, whereas it remains limited for beta-blocker poisonings while evidences are increasing regarding its use in beta-blocker poisonings21. Therefore, it would be beneficial to develop training programs and standardized treatment protocols in France to harmonize clinical practices and promote the use of antidotes in accordance with current scientific evidence.

Interestingly, our original approach based on cases of poisoning requiring an antidote, has highlighted the most frequently implicated agents, distinguishing it from approaches focused on exposure. For example, fomepizole is primarily used for poisonings involving coolant, windshield washer fluid, antifreeze, or methylated spirits, rather than adulterated alcohol. Similarly, calcium gluconate is more often administered in cases of exposure to pure hydrofluoric acid or metal strippers, rather than rustproofing products containing the acid.

This study also shows that trends in antidote use reflect the emergence of new types of poisoning. We observed a significant and growing use of methylene blue (methylthioninium chloride) and cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12). Several studies have reported a marked increase in poisonings caused by methemoglobinemia-inducing agents, such as poppers or sodium nitrite, which are treated with intravenous administration of methylene blue23,48,49,50. Additionally, multiple studies have highlighted the rising incidence of poisonings related to nitrous oxide use31,49, for which the administration of cyanocobalamin is recommended, although its efficacy also relies on stopping substance abuse51,52.

Finally, antidotes are often expensive, and certain antidotes are rare and prone to stock-outs. Antivenom serum combines all these criteria. However, our work shows that they are widely used in France, with more than 1,100 cases requiring their administration. The antivenom serum of reference in France is Viperfav®, which is recommended in cases of grade II and III envenomations by snakes of the Viperidae family53. This study shows how important it is for clinical toxicologists to have effective and available antivenoms, and to alert the health authorities to the need to have sufficient stocks at regional level. In France, a software called SLOGAN (Système de LOcalisation et de Gestion des ANtidotes or Antidote Tracking and Management System) has been created to enable real-time visualization of antidote stocks in hospital pharmacies. This is a mapped network of establishments that provides healthcare professionals with information on the availability of key antidotes in hospital pharmacies. This network is managed by PCCs and is a major asset in optimizing patient referral within facilities and ensuring the loan of certain antidotes between hospitals if necessary. One of the current challenges is to ensure the long-term viability of this solution and roll it out nationwide.

Our study has some limitations, such as the exclusion of certain therapies or cases where the administration of an antidote was not confirmed. The main limitation remains the selection bias. There are several reasons for this. The first is that there is no obligation in France to contact a Poison Center in the event of poisoning. For patients, this is a public service, while for health professionals, it is a request for expert advice that is at their discretion, even if an antidote needs to be administered. Antidotes are generally stored in hospital pharmacies and dispensed by pharmacists, and are not systematically prescribed by toxicologists. The second is that the use of common antidotes, such as NAC, flumazenil or naloxone, is probably underreported as these poisonings and antidotes are generally known to emergency physicians. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that PCs are more likely to be contacted in severe clinical situations or unusual poisonings. This would be the third reason for selection bias. The latter also supports the moderate to severe severity in almost 50% of cases. Furthermore, due to the data available, it was not possible to assess the appropriateness of antidote use in terms of indication, dosage, and timing. A further, updated study would therefore be beneficial and of clinical interest.

However, it also has notable strengths. The main strength is the large number of cases analyzed (n = 25,289) and the extended study period 7 years, which enhances the robustness of the data. This novel approach, focusing on antidote use, has allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the agents involved, as well as a detailed description of the clinical severity of poisonings. This study can serve as a valuable reference by cross-referencing data on the causative agents of poisonings and the severity of clinical outcomes, thereby facilitating increased vigilance for certain agents and potentially informing preventive measures.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide numerous observations of importance to clinicians and toxicologists. Firstly, they provide a clear overview of the epidemiology of poisoning in France through the use of antidotes. They also provide an insight into medical practices over the seven-year period. One of the main observations is that the use of antidotes has remained stable over time; however, there are variations in use depending on the molecule. Fomepizole has gradually replaced ethanol in cases of toxic alcohol poisoning. The increase in the use of methylthioninium chloride and vitamin B12 also indirectly reflects the rise in the recreational use of poppers and nitrous oxide, which were emerging phenomena at the time are still prevalent today, as well as suicide attempts using sodium nitrite. This study also provides a detailed description of the agents involved in poisonings in France, such as the fact that ethylene glycol poisoning is mainly caused by the ingestion of coolant, or that certain banned products, such as organophosphate pesticides, were still responsible for a significant number of poisonings. The study also describes situations in which an antidote is administered that sometimes exceed the main indication. For example, pralidoxime is administered in cases of carbamate poisoning despite its questionable or even non-existent efficacy in such cases. Or that poisoning with oleander sometimes requires the administration of specific anti-digoxin antibodies, whose only official indication is digoxin poisoning.

In summary, this study opens up possibilities for further research and investigation, both on the uses and indications of antidotes and on the clinical situations encountered, thereby making an important contribution to practical toxicological knowledge.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Prevention and management of cases of poisoning. https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/chemical-safety-and-health/incidents-poisonings/prevention-and-management-of-cases-of-poisoning (2024).

Deaths from poisoning, part of the following publication: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser (2016) - “Global Health”. Data adapted from IHME, Global Burden of Disease. https://archive.ourworldindata.org. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-from-poisoning (2025).

Karami M. Principles of toxicotherapy: General & special therapy.

Chacko, B. & Peter, J. V. Antidotes in poisoning. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. Peer-Rev Off. Publ. Indian Soc. Crit. Care Med. 23(Suppl 4), S241–S249 (2019).

Al-Sohaim, S. I., Awang, R., Zyoud, S. H., Rashid, S. M. D. & Hashim, S. Evaluate the impact of hospital types on the availability of antidotes for the management of acute toxic exposures and poisonings in Malaysia. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 31(3), 274–281 (2012).

Buckley, N. A., Dawson, A. H., Juurlink, D. N. & Isbister, G. K. Who gets antidotes? choosing the chosen few. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 81(3), 402–407 (2016).

Dart, R. C. et al. Expert consensus guidelines for stocking of antidotes in hospitals that provide emergency care. Ann. Emerg. Med. 71(3), 314-325.e1 (2018).

Al-Taweel, D. et al. Availability of antidotes in Kuwait: A national audit. J. Emerg. Med. 58(2), 305–312 (2020).

Antidotes and Related Agents: Recognition of Need, Availability, and Effective Use. ISMP Canada. https://ismpcanada.ca/bulletin/antidotes-and-related-agents-recognition-of-need-availability-and-effective-use/ (2025).

Lapostolle, F. et al. Availability of antidotes in French emergency medical aid units. Presse Med. Paris Fr 30(4), 159–162 (2001).

Heard, K. & Green, J. Acetylcysteine therapy for acetaminophen poisoning. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 13(10), 1917–1923 (2012).

Sanders, L. D. et al. Reversal of benzodiazepine sedation with the antagonist flumazenil. Br. J. Anaesth. 66(4), 445–453 (1991).

Sadove, M. S., Balagot, R. C., Hatano, S. & Jobgen, E. A. Study of a narcotic antagonist-N-allyl-noroxymorphone. JAMA 183, 666–668 (1963).

de Haro, L. et al. Envenimations par vipères européennes. Étude multicentrique de tolérance du ViperfavTM nouvel antivenin par voie intraveineuse. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Réanimat. 17(7), 681–687 (1998).

DeZee, K. J., Shimeall, W. T., Douglas, K. M., Shumway, N. M. & O’Malley, P. G. Treatment of excessive anticoagulation with phytonadione (Vitamin K): A meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 166(4), 391–397 (2006).

Peterson, C. D., Leeder, J. S. & Sterner, S. Glucagon therapy for beta-blocker overdose. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 18(5), 394–398 (1984).

Vech, R. L., Lumeng, L. & Li, T. K. Vitamin B6 metabolism in chronic alcohol abuse the effect of ethanol oxidation on hepatic pyridoxal 5’-phosphate metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 55(5), 1026 (1975).

Druteika, D. P., Zed, P. J. & Ensom, M. H. H. Role of fomepizole in the management of ethylene glycol toxicity. Pharmacotherapy 22(3), 365–372 (2002).

Chan, B. S. H. & Buckley, N. A. Digoxin-specific antibody fragments in the treatment of digoxin toxicity. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 52(8), 824–836 (2014).

Mengs, U., Pohl, R. T. & Mitchell, T. Legalon® SIL: the antidote of choice in patients with acute hepatotoxicity from amatoxin poisoning. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 13(10), 1964–1970 (2012).

Engebretsen, K. M., Kaczmarek, K. M., Morgan, J. & Holger, J. S. High-dose insulin therapy in beta-blocker and calcium channel-blocker poisoning. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 49(4), 277–283 (2011).

Beatty, L., Green, R., Magee, K. & Zed, P. A systematic review of ethanol and fomepizole use in toxic alcohol ingestions. Emerg. Med. Int. 2013, 638057 (2013).

Modarai, B., Kapadia, Y. K., Kerins, M. & Terris, J. Methylene blue: a treatment for severe methaemoglobinaemia secondary to misuse of amyl nitrite. Emerg. Med. J. EMJ. 19(3), 270–271 (2002).

Shepherd, G. & Velez, L. I. Role of hydroxocobalamin in acute cyanide poisoning. Ann. Pharmacother. 42(5), 661–669 (2008).

Lheureux, P. E. R. & Hantson, P. Carnitine in the treatment of valproic acid-induced toxicity. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 47(2), 101–111 (2009).

Shea, B. et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013(5), 000951 (2013).

Ward, A., Chaffman, M. O. & Sorkin, E. M. Dantrolene. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in malignant hyperthermia, the neuroleptic malignant syndrome and an update of its use in muscle spasticity. Drugs 32(2), 130–168 (1986).

Roblin, I., Urban, M., Flicoteau, D., Martin, C. & Pradeau, D. First-aid treatment of hydrofluoric acid skin burns with 2.5% calcium gluconate gel: an experimental controlled study. Crit. Care 10(1), P186 (2006).

Salhanick, S. D. & Shannon, M. W. Management of calcium channel antagonist overdose. Drug Saf. 26(2), 65–79 (2003).

Johnson, M. K., Vale, J. A., Marrs, T. C. & Meredith, T. J. Pralidoxime for organophosphorus poisoning. Lancet Lond. Engl. 340(8810), 64 (1992).

McLaughlin, S. A., Crandall, C. S. & McKinney, P. E. Octreotide: an antidote for sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia. Ann. Emerg. Med. 36(2), 133–138 (2000).

Mayall, M. Vitamin B12 deficiency and nitrous oxide. Lancet 353(9163), 1529 (1999).

Moore, P. W., Rasimas, J. J. & Donovan, J. W. Physostigmine is the antidote for anticholinergic syndrome. J. Med. Toxicol. 11(1), 159 (2014).

Picchioni, A. L. Deferoxamine (desferal)—a new antidote for iron poisoning. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 24(9), 524–525 (1967).

van Veen, J. J. et al. Protamine reversal of low molecular weight heparin: clinically effective?. Blood Coagul. Fibrinoly. Int. J. Haemost. Thromb. 22(7), 565–570 (2011).

White, K., Faruqi, U., Cohen, A. & Ander, T. New agents for DOAC reversal: a practical management review. Br. J. Cardiol. 29(1), 1 (2022).

Persson, H. E., Sjöberg, G. K., Haines, J. A. & Pronczuk de Garbino, J. Poisoning severity score. Grading of acute poisoning. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 36(3), 205–213 (1998).

Thanacoody, R. & Anderson, M. Epidemiology of poisoning. Medicine (Baltimore) 48(3), 153–155 (2020).

Salem, W. et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associated cost of acute poisoning: a retrospective study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 17(1), 2325513 (2024).

Asad, A. H., Suryawanshi, V. R. & Raut, A. Epidemiology, severity, and associated factors of poisoning cases and patient outcomes. Epidemiol. Health Syst. J. 11(4), 171–177 (2024).

Rapport Annuel 2023 - InfoTox Suisse. https://www.toxinfo.ch/customer/files/1083/9241306-Tox-Jahresbericht-2023-FR-Web-150dpi.pdf (2025).

Gummin, D. D. et al. 2023 annual report of the national poison data system® (NPDS) from America’s Poison Centers®: 41st annual report. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 62(12), 793–1027 (2024).

Licata, A. et al. N-acetylcysteine for preventing acetaminophen-induced liver injury: A comprehensive review. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 828565 (2022).

Shumaik, G. M., Wu, A. W. & Ping, A. C. Oleander poisoning: treatment with digoxin-specific Fab antibody fragments. Ann. Emerg. Med. 17(7), 732–735 (1988).

Pillay, V. V. & Sasidharan, A. Oleander and datura poisoning: An update. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 23(S4), 0 (2019).

Link, S. L., Rampon, G., Osmon, S., Scalzo, A. J. & Rumack, B. H. Fomepizole as an adjunct in acetylcysteine treated acetaminophen overdose patients: a case series. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 60(4), 472–477 (2022).

Rotella, J. A. et al. Treatment for beta-blocker poisoning: a systematic review. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 58(10), 943–983 (2020).

Lefevre, T., Nuzzo, A. & Mégarbane, B. Poppers-induced life-threatening methemoglobinemia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 198(12), e137–e138 (2018).

Barrangou-Poueys-Darlas, M. et al. Poppers use and high methaemoglobinaemia: ‘Dangerous Liaisons’. Pharmaceuticals 14(10), 1061 (2021).

Vodovar, D., Tournoud, C., Boltz, P., Paradis, C. & Puskarczyk, E. Severe intentional sodium nitrite poisoning is also being seen in France. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 60(2), 272–274 (2022).

Cheng, H. M., Park, J. H. & Hernstadt, D. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord following recreational nitrous oxide use. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, bcr2012008509 (2013).

Brunt, T. M., van den Brink, W. & van Amsterdam, J. Rare but relevant: Nitrous oxide and peripheral neurotoxicity, what do we know?. Addict. Abingdon. Engl. 120(5), 1046–1050 (2025).

Boels, D. et al. Snake bites by European vipers in Mainland France in 2017–2018: comparison of two antivenoms Viperfav® and Viperatab®. Clin. Toxicol. Phila Pa. 58(11), 1050–1057 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: N.D.; Methodology: A.-M.P., I.B.-B., S.G., F.P, N.D.; Formal analysis: A.-M.P., S.G., M.G.; Investigation: A.-M.P., S.G., N.D.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.-M.P., S.G., N.D.; Writing—review and editing: A.-M.P., D.V., N.D.; Supervision: N.D. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. French PCC Research Group members collected the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pouget, AM., Blanc-Brisset, I., Guillotin, S. et al. Trends in antidote use in France from 2015 to 2021: a nationwide poison centers study. Sci Rep 15, 30253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15475-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15475-x