Abstract

Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is a bedside imaging technique in which voltage data arising from current applied on electrodes is used to compute images of admittivity in real time. Due to the severe ill-posedness of the inverse problem, good spatial resolution poses a challenge in EIT. Conversely, the temporal resolution is high, facilitating dynamic bedside imaging. In this work, we propose a real-time linearized reconstruction algorithm that makes use of an anatomical atlas to provide prior spatial information at two stages of the reconstruction with the goal of improving the spatial resolution. The algorithm updates a non-constant initial estimate of an anatomically relevant distribution of conductivity and susceptivity obtained from the mean of the atlas, and using the Schur complement method as a post-processing technique. Two atlases are constructed from a database of CT scans of 89 infants; one for the reconstruction of ventilation and one for the reconstruction of pulsatile perfusion. The algorithm is applied to data collected on 16 premature infants with lung disease of prematurity and 5 healthy control infants to reconstruct conductivity and susceptivity images of both ventilation and pulsatile perfusion in real time using the ACT 5 EIT system. EIT parameters describing homogeneity of ventilation distribution throughout the lung and the distribution anterior/posterior and in the left versus right lung were computed for each infant. The left/right ventilation distribution was found to distinguish between the healthy and the preterm infants with statistical significance (p-value< 0.05). The reconstructions demonstrate qualitatively improved resolution when compared to the NOSER algorithm currently used on the ACT 5 system for real-time bedside imaging, and the ability to image changes due to ventilation and pulsatile perfusion, as well as regional inhomogeneity. Since CT scans were not available for these infants, there is no gold standard for validation. In conclusion, we present a novel real-time algorithm with the goal of improving spatial resolution for bedside imaging with EIT for conductivity and susceptivity imaging of ventilation and pulsatile perfusion, with the potential to aid in the evaluation of lung function in infants at the bedside.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is a bedside imaging modality suitable for patients from birth through adulthood in which low-frequency (10 to 250 kHz), low-amplitude current is applied on electrodes placed circumferentially on the patient’s chest, resulting in voltage data on the electrodes that is used to compute images of changes in conductivity and susceptivity in real time. Cross-sectional dynamic images are formed by solving a nonlinear ill-posed problem to reconstruct the admittivity distribution in the plane of the electrodes for each frame of data. The ill-posedness of the inverse problem results in a sensitivity to noise in the data and the need for high precision voltage measurements. The regularization techniques that are applied to overcome the ill-posedness typically result in images with blurred organ boundaries and lower contrast. While EIT images are of low spatial resolution, the temporal resolution is high, often in excess of 50 frames/s. This makes EIT particularly attractive for bedside imaging and as-needed monitoring since it also imparts no ionizing radiation. EIT has been well-studied for monitoring patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1,2,3,4,5, including those with COVID-196,7,8,9 and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome10,11,12,13. EIT has been used to study ventilation and pulsatile perfusion in preterm infants14,15, including longitudinally16, as well as for optimizing positive end expiratory pressure in ventilated infants17. The effects of suction on mechanically ventilated infants have been studied with EIT18,19,20, as well as the effects of time and body position21. Lung volume and air distribution in preterm infants has been studied using EIT22,23,24,25. Other studies have used EIT to evaluate lung function in neonates26,27. For further background, the reader is directed to review articles on pulmonary applications of EIT28,29,30, and its application to neonatal imaging31.

The primary purpose of this paper is to propose a reconstruction method that provides improved resolution over the standard Newton One-Step Error Reconstructor (NOSER)32 algorithm used in the ACT series of simultaneous multi-current source EIT systems. The MEan Atlas Noser-based (MEAN) algorithm computes a perturbation from a non-constant initial estimate of the conductivity that is obtained from the mean conductivity distribution of a representative anatomical atlas33. The novel improvements proposed here to the MEAN algorithm permit real-time imaging of both conductivity and susceptivity for both ventilation and pulsatile perfusion from clinical data collected on premature infants. The MEAN algorithm was originally developed to compute single-frame images of simulated data for conductivity distributions of ventilation at maximum inspiration. Novel to this work is a more efficient method of computing the Jacobian matrix and the introduction of the susceptivity, which is the imaginary part of a complex conductivity, in the atlas and the MEAN algorithm. Furthermore, the MEAN algorithm is applied for the first time to compute dynamic images of ventilation and pulsatile pulmonary perfusion on human subject data. The reconstruction of pulsatile perfusion in EIT is well-known to be more challenging than ventilation due to the small signal amplitude.

The inclusion of a priori information about features of the conductivity has been shown to be an effective method for improving the low spatial resolution of EIT images. Various techniques for doing this can be found in the literature. Iterative methods34,35,36,37 include an a priori conductivity distribution in the penalty term of the cost functional. The a priori distribution could be based on a patient’s previous CT or MRI scan, an anatomical atlas, or from a generic expected distribution, for example. Multi-step iterative methods have the disadvantage of requiring an accurate forward problem simulation at each iteration, and are therefore challenging to develop and require longer computation times. Care must be taken when the prior is in the penalty term not to bias the solution towards the prior by over-weighting the penalty term. Edge-preserving techniques38,39 make use of the knowledge that organ boundaries correspond to discontinuities in the conductivity distribution and improve resolution by promoting those features. However, including a priori knowledge of the conductivity distribution itself requires combining these techniques with other approaches, which may be quite promising. Bayesian approaches39,40,41,42 provide a natural framework for including a priori information, but have the drawback of requiring longer computation times. While much progress has been made in developing faster algorithms, real-time reconstruction still remains a challenge to be met. More recently Finite Element Method (FEM) grouping43 has been proposed to simultaneously reduce ill-posedness and computational cost by using an adaptive FEM scheme and Tikhonov regularization with an \(H^1\) seminorm penalty. While this method is promising with its improved efficiency and proven convergence in the sense of providing a sequence that converges to the solution of the optimality system for the continuous situation, it also does not provide real-time reconstructions, and a priori information is included in the penalty term. Additionally, many machine learning approaches have been proposed. At the time of this writing, it is arguably the fastest-growing body of approaches. Examples of machine learning algorithms for EIT imaging include end-to-end reconstruction approaches44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58 and post-processing of EIT reconstructions59,60,61,62,62. However, it is a well recognized concern that machine approaches introduce a black box solution that is not readily analyzed as to how the solution is produced. Our work differs from the above approaches in that the information from the anatomical atlas serves as a starting point for the algorithm, which assumes that the solution is a perturbation from the mean admittivity distribution of the atlas and takes one iterative step toward a solution that provides better fidelity to the data. The single iteration facilitates real-time reconstructions. In this work we study further improvement in resolution by applying a post-processing technique known as the Schur complement method to the MEAN reconstruction. The Schur complement method was introduced to improve the resolution of D-bar images63, and has been extended here to post-process the susceptivity images for the first time.

This is the first work in which the MEAN and MEAN + Schur complement methods are applied to a suite of dynamic human subject EIT data sets to image ventilation and pulsatile perfusion in infants. As a secondary goal of this paper, we study the images and several EIT-derived measures from an archival EIT data set collected at Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHCO) on 16 preterm infants with lung disease of prematurity and 5 healthy full-term infants.

Extremely preterm infants are at high risk of developing a chronic lung diseases known as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). BPD is the most common cause of lung disease in infants64 and affects 10,000–15,000 premature infants in the United States every year65. Extremely preterm infants, defined to be those born at gestational age 28 weeks or younger, are at high risk of neonatal mortality66. Infants with BPD present with a variable mix of parenchymal, airway, and pulmonary vascular disease that results in a heterogeneous lung architecture with areas of atelectasis and over-expansion67,68. Imaging this heterogeneity could inform treatment strategies including medications and ventilatory settings. In this work we demonstrate the ability of our algorithm to capture heterogeneity in the infants’ lungs. Validation of the results will be a subject of future study.

Methods

The 2-D generalized Laplace equation serves as the mathematical model for the inverse problem of EIT69 for the reconstruction of the unknown admittivity. The admittivity will be denoted by \(\gamma (x,y) = \sigma (x,y)+i\omega \epsilon (x,y)\), where \(\sigma (x,y)\) is the conductivity, \(\omega\) is the frequency of the applied current, and \(\epsilon (x,y)\) is the electric permittivity. The quantity \(\omega \epsilon\) is known as the susceptivity.

The anatomical atlases

Construction from CT scans

In order to implement prior information about the typical infant anatomy, two anatomical atlases were developed to capture general structures of infant bodies and to represent average conductivity and susceptivity tissue values when alternating current is applied at 93 kHz during ventilation and pulsatile perfusion. The atlases were built from CT scans of 89 infants aged 0 to 3 months, acquired from the New Mexico Decedent Database70. Upon receipt and selection of applicable data, the scans were then segmented into tissues of varying electrical properties using the ITK-SNAP71 software. Based on the visible contrast of the scans, the scans were able to be segmented into soft tissue, trachea, lung, and bone. However the scans did not allow for systematic segmentation of the heart, and a representative average heart was manually placed in the center of the chest cavity.

The three-dimensional segmentation models were then saved as neuroimaging information technology initiative (NIFTI) files and imported into Seg3D 2.5.172 to divide into two-dimensional tomographic images in the transverse plane. A total of 8,171 slices containing lung tissue were retained to be used in constructing the anatomical atlas.

The slices were then imported into MATLAB73 for processing. For each slice, the boundaries between each tissue type were found and randomized conductivity and susceptivity values at 93 kHz74,75 were applied for that tissue type according to the statistical tissue descriptions during ventilation and perfusion processes as shown in Table 1. This randomization process was repeated 10 times for each slice to result in a complete dataset of 81,710 axial slices for each of the two atlases, one to represent ventilation, and one to represent perfusion.

Domain shape modeling

Since the true contour of the torso is unknown for the human subjects in our archival data set, a canonical infant shape was used for the EIT recontruction mesh. Each 2-D slice in the atlas was conformally mapped to this canonical shape. An example of one of these mappings of the conductivity distribution is shown in Fig. 1a. After conformally mapping each slice, the mean over all of the distributions is computed from a pixel-wise averaging of complex admittivity values across each of the two atlases. Reconstructions were computed on the Joshua tree mesh, which was introduced on a circlular domain32, conformally mapped to the canonical infant shape (Fig. 2). The mean of each atlas was discretized to the conformally mapped Joshua tree mesh using the nearest-neighbor to the centroid of each component. The MEAN initial admittivity estimate for ventilation is shown in Fig. 1b.

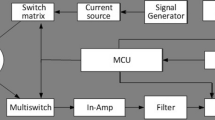

Voltage data simulation

Since data sets collected on infants with the ACT 5 EIT system76 were the targeted application in this work, simulations were designed to mimic data collected with ACT 5. Voltages arising from trigonometric current patterns were computed using a 2-D finite element method (FEM) with approximately 18,000 elemeents using the complete electrode model (CEM)69. ACT 5 applies linearly independent trigonometric current patterns defined for L electrodes by

where \(\theta _\ell = \frac{2\pi \ell }{L}\) represents the angle from a central reference point in the body to the \(\ell\)th electrode. In the simulations, the current amplitude was \(M=0.35\ mA\), and \(L=\)16 electrodes with a width and height of 3.3 cm were applied. The CEM accounts for the shunting effect of the electrodes and the contact impedance between the electrodes and tissue, which was set to \(z=0.05\ \Omega \cdot m^2\). Measured voltages were computed for each slice of the anatomical atlas separately, with a constant admittivity distribution extended in the transverse plane with a height of 3.3 cm, corresponding to the electrode height. No corrections were made to account for out-of-plane effects in the simulations. Noise simulating that of the ACT 5 EIT system was included by adding random Gaussian noise of magnitude 0.1% of the maximum voltage signal to the matrix of simulated voltages.

The MEAN atlas NOSER-based algorithm

As in the NOSER algorithm32, a linearized least-squares approach is taken to find an admittivity distribution that minimizes the error between the measured and simulated voltages. Denote the voltage measured on the \(\ell\)th electrode arising from the kth current pattern by \(V_{\ell }^k\). Since only one step in the iterative algorithm is taken, we only need to compute simulated voltages corresponding to the initial estimate in the algorithm, \(\bar{\gamma }\). These will be denoted by \(U_{\ell }^k\), and were computed using the method in Section 2.1.

Reconstructions were computed on the canonical infant torso shape using a 2-D Joshua tree mesh of \(N=496\) elements mapped to that shape as in Fig. 2. Assuming the admittivity is constant on each mesh element, for any point (x, y) in the canonical domain, we can write

where \(\chi _n\) is the characteristic function for the nth mesh element, which we denote \({\Omega _n}\). Let \(\varvec{\gamma }\) be the vector with entries \(\gamma _n\). Then we seek to solve the minimization problem

A necessary condition for a minimizer is \(\frac{\partial E(\varvec{\gamma })}{\partial \gamma _n} = 0\), or

We then wish to solve

Taking one step in a Gauss-Newton method with initial guess \(\varvec{\bar{\gamma }}\) to solve (5) results in an approximation \(\varvec{\hat{\gamma }}\) to the admittivity given by

where \(\varvec{F}'(\varvec{\bar{\gamma }})\) is the Jacobian matrix of \(\varvec{F}\) with entries

Taking a linearized approximation to (7) results in32

To compute the partials, we expand \(\frac{\partial \varvec{U}^k(\varvec{\bar{\gamma }})}{\partial \gamma _n}\) in the basis of trigonometric current patterns \(\varvec{T^k}=[T_1,\ldots ,T_L]\) as follows:

Representing \(\langle \varvec{T}^s,\varvec{U}^k\rangle\) as a discretization of the integral

and differentiating the right side with respect to \(\gamma _n\), we see

For the last two terms, we integrate by parts and differentiate the governing equations of EIT with respect to \(\gamma _n\) to find

Differentiating (2) we see \(\frac{\partial \gamma }{\partial \gamma _n} = 1\) on \(\Omega _n\) and 0 elsewhere. Recognizing that the dot product is commutative, we can exchange s and k and substitute into (11) and further discretize to find

where \(E_j\) denotes a triangular element the FEM forward solution mesh. The gradients \(\nabla u^k_j\) are estimated on each triangular element \(E_j\) of the FEM mesh by computing the gradient of the unique plane that passes through the three points \((\varvec{x}, u^k(\varvec{x},\varvec{\bar{\gamma }}))\) making up the element. The integration is further discretized by summing over each element with center located within the nth component, \(\Omega _n\), of our conformally remapped Joshua tree mesh. This approach allows the gradients to be efficiently estimated using a single solving of the forward problem for each current pattern.

Finally, we note that the matrix \(\varvec{F'}(\varvec{\tilde{\gamma }})\) as computed above is ill-conditioned, and so in practice we regularize the matrix using a two-step process. First, let the matrix A be defined by its entries

where \(\delta _{n,m}\) is the Kronecker delta function, and \(\beta\) is a regularization parameter, chosen empirically, which will ensure A is diagonally dominant and positive definite if chosen sufficiently large. Next, let

where \(\alpha\) is a second regularization parameter, determined empirically. For the reconstructions shown in Section 3, the regularization parameters were \(\beta = 20\) and \(\alpha = 0.00025\).

Finally, the reconstructed admittivity distribution is computed from the formula

Note that the MEAN algorithm computes absolute images, and time-difference images are formed by subtracting two absolute images.

Schur complement

In addition to allowing us to compute and implement an improved initial condition for the NOSER method, the anatomical atlas can be used to post-process reconstructed images based on prior statistical data using a Schur Complement property63,77. The conductivity and susceptivity are post-processed separately, but analogously, so we describe the method for the conductivity here.

Since we have known numerical phantoms \(\varvec{\sigma }\) for each image in our anatomical atlas, we can compute a covariance matrix, \(\Gamma\), of the joint distribution between each pixel in the numerical phantom images and the corresponding conductivity distribution on the Joshua tree mesh given by \(\varvec{\hat{\sigma }}\). Writing \(\Gamma\) as a block matrix,

where \(\Gamma _{\varvec{\sigma \sigma }}\) and \(\Gamma _{\varvec{\hat{\sigma }\hat{\sigma }}}\) are the covariance matrices of the numerical phantom and reconstruction images, respectively, and \(\Gamma _{\varvec{\sigma \hat{\sigma }}} = \Gamma _{\varvec{\hat{\sigma }\sigma }}^\intercal\) represent the cross-covariance matrices. Letting \(\varvec{\mu _\sigma }\) and \(\varvec{\mu _{\hat{\sigma }}}\) denote the pixel-wise means of each numerical phantom image and segment-wise mean of the corresponding MEAN reconstructions, respectively, we suppose we have a joint multivariate Gaussian distribution of \(\varvec{\sigma }\) and \(\varvec{\hat{\sigma }}\) given by

As a covariance matrix, \(\Gamma\) is a symmetric positive definite matrix, so the Schur complements of \(\Gamma\) are defined by

which we use to rewrite \(\Gamma ^{-1}\) in the form78

Then, for a given reconstruction \(\varvec{\hat{\sigma }}\), the conditional distribution is of the form78

from which the expected value of the true conductivity distribution given a reconstructed image \(\varvec{\hat{\sigma }}\) is given by

In practice, since \(\Gamma _{\varvec{\hat{\sigma }\hat{\sigma }}}\) is typically ill-conditioned we regularize the matrix using diagonal ridge regression by adding a diagonal term \(\kappa I\) using \(\kappa = 10^{-3}\). This updated estimate of \(\mathbb {E}(\varvec{\sigma }|\varvec{\hat{\sigma }})\) is the Schur complement post-processed reconstruction of the conductivity distribution. That is,

For implementation, we recognize that this equation can be rewritten in the form \(\varvec{\hat{\sigma }}_S = \varvec{A}_{\kappa }\varvec{\hat{\sigma }} + \varvec{b}_\kappa\) where we precompute

allowing post-processing to be performed as a single matrix multiplication and addition, adding a minimal amount of time to processing.

Since the admittivity distribution provides us with images of both the conductivity and susceptivity, we can follow the same process to post-process output susceptivitity images as well, resulting in a Schur post-processed admittivity distribution \(\varvec{\hat{\gamma }}_S = \varvec{\hat{\sigma }}_S + i\varvec{\widehat{\omega \epsilon }}_S\).

Human subject data collection

The archival EIT data were collected at Children’s Hospital Colorado as part of a larger study and under the approval of the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) (approval number COMIRB 18-1843), Aurora, CO. Informed parental consent was obtained prior to participation. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all relevant guidelines and regulations. In that study EIT data were collected every 4-5 weeks on each patient for up to five visits or until discharge. Each EIT data collection period is referred to as a “visit”, and so each visit is 4 to 5 weeks later than the previous one. Control subjects were only imaged once. Reconstructions of pulsatile perfusion were computed from data collected during a breath pause identified by the power waveform as opposed to using bandpass filtered EIT signals. Due to the high SNR of the ACT 5 data76, we do not need to average or filter the voltage data to compute these reconstructions.

Reconstructions on three representative subjects, A, B, and C are presented in the following section. The healthy control, Subject A, was an infant born at 40 weeks gestational age and imaged at 106 days chronological age. Subjects B and C were male twins born prematurely at 28 weeks gestational age. Subject B received 3 imaging visits. Subject B was imaged first at 19 days chronological age while receiving ventilatory support through continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Visit 2 was at 51 days on low flow nasal cannula. At Visit 3 the patient was still receiving low flow nasal cannula and diagnosed with lung disease of prematurity. The infant was discharged from the hospital after Visit 3. Subject C is the twin of Subject B and was diagnosed with Grade 3 BPD and received 5 imaging visits. Visit 1 was at 19 days chronological age, while the patient was receiving CPAP. Visit 2 was at 51 days chronological age, on invasive mechanical ventilation. Visit 3 was at 79 days chronological age, while the patient was receiving oxygen via high flow nasal cannula. Visit 4 was at 106 days chronological age, with high flow nasal cannula. Visit 5 was at 136 days chronological age, still with high flow nasal cannula.

Derived measures and statistical analysis

The global inhomogeneity (GI) index79, anterior/posterior center of ventilation (CoV), and left/right lung ventilation distribution were computed for each of the 16 preterm infants at the visit closest to gestational age 36 weeks, since that this is the age at which a diagnosis of BPD is made, and for each of the 5 healthy full-term infants. The GI index was computed from the conductivity difference image \(\varvec{DI} \equiv \hat{\varvec{\sigma }}(t_{insp}) -\hat{\varvec{\sigma }}(t_{exp})\), where \(t_{insp}\) represents end-inspiration and \(t_{exp}\) end-expiration for each breath, on a segmentation of the lung region, Lung, using the formula

The reported GI index value was taken as the mean value across all recorded breaths. The anterior/posterior CoV was found as follows. First, the estimated volumes of air80 in each element of the Joshua tree mesh were found and mapped to a 64x64 image of square pixels. Since each element of the 64x64 mesh may contain multiple pixels, air volume was assumed be uniformly distributed among all pixels contained in any specific component \(\Omega _n\). Then, starting with the posterior-most row of the image the cumulative air volume was computed with the CoV defined to be the distance to the first row in which the cumulative volume exceeds half of the total tidal volume. This position is presented as a percentage of the distance from the posterior-most position on the domain to the anterior-most position on the domain. The left/right lung ventilation distribution is found by assigning each component \(\Omega _n\) to the left and right side of the body. The air volume contained on the right side is accumulated and found as a percentage of the total computed air volume at end-inspiration. An unequal variance (independent) t-test was used to analyze whether each measure could distinguish between healthy controls and the patients with lung disease.

Code availability

Code implementing the MEAN algorithm can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/cjrocheleau/MEAN_EIT_Algorithm

Results and discussion

Statistical results

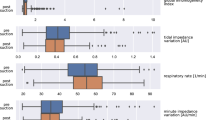

The right/left ventilatory volume distribution of air at full inspiration was found to distinguish between the healthy subjects and those with chronic lung disease with statistical significance (\(p < 0.05\)). Computations of the anterior/posterior center of ventilation (CoV) and the global GI index did not distinguish between the groups with statistical significance. The box-whisker plot for the right/left ventilatory volume distribution is found in Fig. 3. Sample statistics corresponding to images shown in sections 3.3-3.5 are presented in Table 2.

Reconstructed images

CT scans were not performed on these subjects, and so there is no adjunct modality for comparison of anatomical structure in the reconstructions. However, the inclusion of a healthy control, and comparison to NOSER images demonstrate qualitatively the improved spatial resolution of the proposed approaches. Reconstructions of difference images of conductivity and susceptivity are presented in Figs. 4,5,6 for each patient’s visits. After an approximately 30 second initialization period to compute the gradients for a specific subject, the MEAN reconstruction takes on average 10 ms for each frame of current patterns on a Ryzen 7 3.20 GHz CPU, 16 GB RAM laptop computer, or 13 ms including the Schur post-processing. For comparison, processing took 7 ms and 7.7 ms for MEAN and MEAN with Schur post-processing, respectively, on a Core i7 3.40 GHz CPU, 64 GB RAM desktop computer. Since data for a full set of current patterns takes 18 ms to collect, results can be computed and displayed in real time.

All ventilation images shown in this section are difference images at full inspiration with reference image at full expiration. Pulsatile perfusion images are difference images at a frame chosen at the end of T-wave, expected to be systole, identified from the EIT ECG, with a reference frame at the end of the QRS complex. Images were normalized and displayed using identical contrast ranges and presented in arbitrary units (A.U.).

Subject A: control case

Comparisons of the reconstruction methods to NOSER for visualizing ventilation and pulsatile perfusion are shown in Fig. 4a and b, respectively, for data collected on the healthy control infant. For this subject, the NOSER ventilation difference image shows a large ventilated region with little definition between the two lungs, and the heart is not visible. The MEAN and Schur images show clear lung definition in both the conductivity and susceptivity images, with the right lung slightly larger than the left, as is expected in a healthy infant. All of the reconstructions show both lungs being well-ventilated, as would be expected as well. In the conductivity and susceptivity images post-processed by Schur, a large, well-defined heart region is present, very similar to the shape one sees in the mean of the atlas in Fig. 1b. This may be an artefact potentially caused by overweighting of the contribution of the atlas, but was not mitigated by decreasing the parameter \(\kappa\), at least not to the extent that a reasonable image was still preserved.

When studying the NOSER reconstruction of the pulsatile perfusion difference image of the healthy infant in Fig. 4b the lungs are filled with blood as expected during the systole phase. In each of the images, one sees that the heart is less conductive than in the reference frame, and therefore contains less blood, and the lungs are more conductive than in the reference frame, therefore containing more blood. In the both the MEAN images, the lung region is larger than that of the NOSER reconstruction. The Schur reconstructions again have a large, well-defined heart, that may be due to bias from the atlas.

Subject B: lung disease of prematurity

Figure 5a and b contain the ventilation and pulsatile perfusion difference images for the three visits with images displayed on the same scale across visits. The ventilation difference images for Visit 1 show a high degree of heterogeneity with a GI Index of 0.63, with only 29.8% of total lung volume contained within the right lung. The ventilatory balance improves with Visits 2 and 3, and the heterogeneity decreases with GI indices of 0.30 and 0.38, respectively. The pulsatile perfusion images are more homogeneous than the ventilatory images. It is to be noted that the possible large heart artefact is also present in the Schur complement pulsatile perfusion images for Subject B for all three visits.

Subject C: Grade 3 BPD

Figure 6a and b contain the ventilation and pulsatile perfusion difference images for Subject C for the five visits. In this case the NOSER ventilation images for Visit 1 show clear definition of the lungs with right slightly less ventilated than the left. Subsequent visits show less overall ventilation in the NOSER images. That is, the conductivity of the lungs show a much smaller decrease in value at full inspiration compared to the reference image of full expiration than they do for Visits 1 and 2. This may be attributable to the use of the high flow nasal cannula in Visits 2 - 5 as opposed to invasive ventilation in Visit 1. The same phenomenon holds true in MEAN reconstructions for Visits 3, 4, and 5, although to a lesser extent. Inhomogeneity in the aerated region is also evident in both conductivity and susceptivity images. The Schur images show a large well-defined heart, similar to what was observed for the healthy control infant. The pulsatile perfusion difference images for all five visits in Fig. 6b demonstrate fairly homogeneous pulsatile perfusion to both lungs. However, the dynamic range is smaller in Visits 2, 3, 4, and 5 than in Visit 1. As a representative sample of real-time display, movies of the reconstruction sequences for ventilation and pulsatile perfusion for each of the methods during Visit 1 can be found in the supplemental data.

Further discussion and limitations

While ventilatory heterogeneity is apparent to the eye in the ventilation images, it was not well-captured by the GI index. This lack of sensitivity could be due to a canceling-out effect between larger homogeneous regions and smaller one with inhomogeneities.

A consideration surrounding the pulsatile perfusion reconstructions is that the reconstruction may not account for collapse of small pulmonary vessels and is influenced by their distensibility and the patency of the pulmonary microvascular bed81. An injection of hypertonic saline solution has been suggested and used in some studies as an EIT contrast agent to measure perfusion82. However, this technique is generally unsafe for use in infants, and the measurement of pulsatility has been shown to correlate well with stroke volume measured by thermodilution83.

The presence of the larger heart in the reconstructions post-processed by the Schur complement method is conjectured to be caused by a high variance that was observed upon inspection of the matrix \(\Gamma _{\sigma \hat{\sigma }}\) in the Schur complement method. This could result in an over-estimate of the weighting of heart pixels in the post-processing formula. One strategy to mitigate this could be to take a dynamic post-processing approach that accounts for each frame’s timing in the cardiac cycle. However, the development of such a technique is beyond the scope of this paper.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the effectiveness on in vivo EIT data of a novel Newton One-Step Error Reconstruction Method in which the initial condition in the algorithm is derived from the mean of an anatomical atlas created from CT scans from infants age 0 to 3 months. EIT images are characteristically low resolution due to the severe ill-posedness of the inverse problem, and this approach addresses that issue by providing the algorithm with a starting point that is closer to the patient’s true anatomy than a constant. The method is coined “MEAN” due to the choice of the mean of the infant atlas as the initial guess. The resolution is further improved by the application of a post-processing technique known as the Schur complement method to the MEAN reconstruction. The MEAN approach was introduced for simulated data33, and this is the first application of the method to human data. The method has also been extended here to apply to complex valued conductivities - that is, reconstructions of both conductivity and susceptivity. The Schur complement method has also been extended here to post-process the susceptivity images. Both methods run in real time on the ACT 5 EIT system.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Cinnella, G. et al. Physiological effects of the open lung approach in patients with early, mild, diffuse acute respiratory distress syndrome: An electrical impedance tomography study. Anesthesiology 123, 1113–1121 (2015).

Franchineau, G. et al. Bedside contribution of electrical impedance tomography to setting positive end-expiratory pressure for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-treated patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Critical Care Medicine 196, 447–457 (2017).

Heines, S. J. H., Strauch, U., van de Poll, M. C. G., Roekaerts, P. M. H. J. & Bergmans, D. C. J. J. Clinical implementation of electric impedance tomography in the treatment of ARDS: a single centre experience. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. (2018).

Pulletz, S. et al. Dynamics of regional lung aeration determined by electrical impedance tomography in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Multidiscip Respir. Medicine 7, 44 (2012).

Spadaro, S. et al. Variation of poorly ventilated lung units (silent spaces) measured by electrical impedance tomography to dynamically assess recruitment. Critical care (London, England) 22, 26 (2018).

Cardinale, M. et al. Lung-dependent areas collapse, monitored by electrical impedance tomography, may predict the oxygenation response to prone ventilation in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical Care Medicine https://doi.org/10.1515/cdbme-2021-2070 (2022).

Chen, R., Lovas, A., Benyó, B. & Moeller, K. Electrical impedance tomography might be a practical tool to provide information about COVID-19 pneumonia progression. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 7, 276–278. https://doi.org/10.1515/cdbme-2021-2070 (2021).

Morais, C. C. A. et al. Bedside electrical impedance tomography unveils respiratory chimera in COVID-19. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 203, 120–121. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202005-1801IM (2021) (PMID: 33196303).

van der Zee, P., Somhorst, P., Endeman, H. & Gommers, D. Electrical impedance tomography for positive end-expiratory pressure titration in COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Critical Care Medicine 202, 280–284. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0816LE (2020) (PMID: 32479112).

Chatziioannidis, I., Samaras, T. & Nikolaidis, N. Electrical impedance tomography: a new study method for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome?. Hippokratia 15, 211 (2011).

Chatziioannidis, I., Samaras, T., Mitsiakos, G., Karagianni, P. & Nikolaidis, N. Assessment of lung ventilation in infants with respiratory distress syndrome using electrical impedance tomography. Hippokratia 17, 115 (2013).

Miedema, M., De Jongh, F. H., Frerichs, I., Van Veenendaal, M. B. & Van Kaam, A. H. Changes in lung volume and ventilation during lung recruitment in high-frequency ventilated preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome. The J. pediatrics 159, 199–205 (2011).

Rahtu, M. et al. Early recognition of pneumothorax in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome with electrical impedance tomography. Am. J. Respir. Critical Care Medicine 200, 1060–1061 (2019).

Tingay, D. G., Waldmann, A. D., Frerichs, I., Ranganathan, S. & Adler, A. Electrical impedance tomography can identify ventilation and perfusion defects: a neonatal case. Am. J. Respir. Critical Care Medicine 199, 384–386 (2019).

Enzer, K. G. et al. Electrical impedance tomography imaging of ventilation and perfusion in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Perinatol. 1–3 (2025).

Enzer, K. et al. Longitudinal characterization of ventilation and perfusion in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia using electrical impedance tomography. In C26. NOVEL TECHNOLOGIES AND IMAGING APPROACHES IN PEDIATRIC RESPIRATORY MEDICINE, A5161–A5161 (American Thoracic Society, 2024).

LaVita, C. J. et al. Identifying optimal positive end expiratory pressure with electrical impedance tomography guidance in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. In Respiratory Care, vol. 68, 3951869 (Daedalus Enterprises Inc., 2023).

van Veenendaal, M. B. et al. Effect of closed endotracheal suction in high-frequency ventilated premature infants measured with electrical impedance tomography. Intensive care medicine 35, 2130–2134 (2009).

Hough, J. L., Shearman, A. D., Liley, H., Grant, C. A. & Schibler, A. Lung recruitment and endotracheal suction in ventilated preterm infants measured with electrical impedance tomography. J. Paediatr. Child Heal. 50, 884–889 (2014).

Händel, C. et al. Effect of routine suction on lung aeration in critically ill neonates and young infants measured with electrical impedance tomography. Sci. Reports 13, 20842 (2023).

Hough, J., Trojman, A. & Schibler, A. Effect of time and body position on ventilation in premature infants. Pediatr. research 80, 499–504 (2016).

Bhatia, R., Davis, P. G. & Tingay, D. G. Regional volume characteristics of the preterm infant receiving first intention continuous positive airway pressure. The J. pediatrics 187, 80–88 (2017).

van der Burg, P. S., Miedema, M., de Jongh, F. H., Frerichs, I. & van Kaam, A. H. Changes in lung volume and ventilation following transition from invasive to noninvasive respiratory support and prone positioning in preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 77, 484–488 (2015).

Inany, H. S., Rettig, J. S., Smallwood, C. D., Arnold, J. H. & Walsh, B. K. Distribution of ventilation measured by electrical impedance tomography in critically ill children. Respir. Care 65, 590–595 (2020).

Rossi, F. d. S., Yagui, A. C. Z., Haddad, L. B., Deutsch, A. D. & Rebello, C. M. 2013. Electrical impedance tomography to evaluate air distribution prior to extubation in very-low-birth-weight infants: a feasibility study. Clinics 68, 345–350 (2013).

Gaertner, V. D., Mühlbacher, T., Waldmann, A. D., Bassler, D. & Rüegger, C. M. Early prediction of pulmonary outcomes in preterm infants using electrical impedance tomography. Front. pediatrics 11, 1167077 (2023).

Kallio, M. et al. Electrical impedance tomography reveals pathophysiology of neonatal pneumothorax during nava. Clin. case reports 8, 1574–1578 (2020).

de Castro Martins, T. et al. A review of electrical impedance tomography in lung applications: Theory and algorithms for absolute images. Annu. Rev. Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2019.05.002 (2019).

Holder, D. S. Electrical impedance tomography: methods, history and applications (CRC Press, 2004).

Frerichs, I. et al. Chest electrical impedance tomography examination, data analysis, terminology, clinical use and recommendations: consensus statement of the translational EIT development study group. Thorax 72, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208357 (2017).

Ako, A. A., Ismaiel, A. & Rastogi, S. Electrical impedance tomography in neonates: a review. Pediatr. Res. 1–11 (2025).

Cheney, M., Isaacson, D., Newell, J., Simske, S. & Goble, J. NOSER: an algorithm solving the inverse conductivity problem. Int’l J. Imaging Syst. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ima.1850020203 (1990).

Howard, K. et al. A comparison of techniques to improve pulmonary EIT image resolution using a database of simulated EIT images (2024).

Avis, N. J. & Barber, D. C. Incorporating a priori information into the Sheffield filtered backprojection algorithm. Physiol. Meas. 16, A111–A122 (1995).

Dehghani, H., Barber, D. C. & Basarab-Horwath, I. Incorporating a priori anatomical information into image reconstruction in electrical impedance tomography. Physiol. Meas. 20, 87–102 (1999).

Dobson, D. & Santosa, F. An image-enhancement technique for electrical impedance tomography. Inverse Probl. 10, 317–334 (1994).

Kaipio, J. P., Kolehmainen, V., Vauhkonen, M. & Somersalo, E. Inverse problems with structural prior information. Inverse Probl. 15, 713 (1999).

Hamilton, S. J., Hauptmann, A. & Siltanen, S. A data-driven edge-preserving d-bar method for electrical impedance tomography. Inverse Probl. Imaging 8, 1053–1072. https://doi.org/10.3934/ipi.2014.8.1053 (2014).

Harhanen, L., Hyvönen, N., Majander, H. & Staboulis, S. Edge-enhancing reconstruction algorithm for three-dimensional electrical impedance tomography. SIAM J. on Sci. Comput. 37, B60–B78. https://doi.org/10.1137/140971750 (2015).

Dimas, C., Alimisis, V. & Sotiriadis, P. P. Electrical impedance tomography using a weighted bound-optimization block sparse bayesian learning approach. In 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), 243–248, https://doi.org/10.1109/BIBE55377.2022.00058 (2022).

Pham, Q. H. & Hoang, V. H. Bayesian inversion for electrical impedance tomography by sparse interpolation. Inverse Probl. Imaging 19, 1037–1074. https://doi.org/10.3934/ipi.2025007 (2025).

Roininen, L., Huttunen, J. & Lasanen, S. Whittle-matérn priors for bayesian statistical inversion with applications in electrical impedance tomography. Inverse Probl. Imaging 8, 561–586. https://doi.org/10.3934/ipi.2014.8.561 (2014).

Jin, B., Xu, Y. & Zou, J. A convergent adaptive finite element method for electrical impedance tomography. IMA J. Numer.Analysis 37, 1520–1550, https://doi.org/10.1093/imanum/drw045 (2016).

Adler, A. & Guardo, R. A neural network image reconstruction technique for electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Transactions on Med. Imaging 13, 594–600. https://doi.org/10.1109/42.363109 (1994).

Hu, D., Lu, K. & Yang, Y. Image reconstruction for electrical impedance tomography based on spatial invariant feature maps and convolutional neural network. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/IST48021.2019.9010151 (2019).

Manning, M. et al. A deep neural network for a hemiarray eit system. Appl. Math. for Mod. Challenges 1, 39–60. https://doi.org/10.3934/ammc.2023004 (2023).

Martin, S. & Choi, C. T. M. Nonlinear electrical impedance tomography reconstruction using artificial neural networks and particle swarm optimization. IEEE Transactions on Magn. 52, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2015.2488901 (2016).

Michalikova, M., Abed, R., Prauzek, M. & Koziorek, J. Image reconstruction in electrical impedance tomography using neural network. In 2014 Cairo International Biomedical Engineering Conference (CIBEC), 39–42, https://doi.org/10.1109/CIBEC.2014.7020959 (2014).

Wei, Z., Liu, D. & Chen, X. Dominant-current deep learning scheme for electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Transactions on Biomed. Eng. 66, 2546–2555. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2019.2891676 (2019).

Wei, Z. & Chen, X. Induced-current learning method for nonlinear reconstructions in electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Transactions on Med. Imaging 39, 1326–1334. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2019.2948909 (2020).

Fan, Y. & Ying, L. Solving electrical impedance tomography with deep learning. J. Comput. Phys. 404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2019.109119 (2020).

Huang, S.-W., Cheng, H.-M. & Lin, S.-F. Improved imaging resolution of electrical impedance tomography using artificial neural networks for image reconstruction. In 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 1551–1554, https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2019.8856781 (2019).

Li, X. et al. An image reconstruction framework based on deep neural network for electrical impedance tomography. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 3585–3589, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296950 (2017).

Ren, S., Guan, R., Liang, G. & Dong, F. Rcrc: A deep neural network for dynamic image reconstruction of electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 70, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2021.3092061 (2021).

Seo, J. K., Kim, K. C., Jargal, A., Lee, K. & Harrach, B. A learning-based method for solving ill-posed nonlinear inverse problems: A simulation study of lung eit. SIAM J. on Imaging Sci. 12, 1275–1295. https://doi.org/10.1137/18M1222600 (2019).

Tan, C., Lv, S., Dong, F. & Takei, M. Image reconstruction based on convolutional neural network for electrical resistance tomography. IEEE Sensors J. 19, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2018.2876411 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Shape reconstruction with multiphase conductivity for electrical impedance tomography using improved convolutional neural network method. IEEE Sensors J. 21, 9277–9287. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3050845 (2021).

Yang, D., Li, S., Zhao, Y., Xu, B. & Tian, W. An eit image reconstruction method based on densenet with multi-scale convolution. Math. Biosci. Eng. 20, 7633–7660. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2023329 (2023).

Martin, S. & Choi, C. A post-processing method for three-dimensional electrical impedance tomography. Sci Rep 7, 7212 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. V-shaped dense denoising convolutional neural network for electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation Meas. 71, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3166177 (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Deepeit: Deep image prior enabled electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Mach. Intell. 45, 9627–9638. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3240565 (2023).

Cen, S., Jin, B., Shin, K. & Zhou, Z. Electrical impedance tomography with deep calderón method. J. Comput. Phys. 493, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2023.112427 (2023).

Santos, T. B. R., Nakanishi, R. M., Kaipio, J. P., Mueller, J. L. & Lima, R. G. Introduction of sample based prior into the D-bar method through a Schur complement property. IEEE Transactions on Med. Imaging 39, 4085–4093 (2020).

Stoll, B. J. et al. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA 314, 1039–1051, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10244 (2015).

Stenmark, K. R. & Abman, S. H. Lung vascular development: Implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 623–661. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.102229 (2005) (PMID: 15709973).

Howson, C. P., Kinney, M. V., McDougall, L., Lawn, J. E. & Born Too Soon Preterm Birth Action Group. Born too soon: preterm birth matters. Reproductive health 10 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S1 (2013).

Jobe, A. H. The new BPD. NeoReviews 7, e531–e545 (2006).

Coalson, J. J. Pathology of new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. In Seminars in neonatology, vol. 8, 73–81 (Elsevier, 2003).

Somersalo, E., Cheney, M. & Isaacson, D. Existence and uniqueness for electrode models for electric current computed tomography. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 52, 1023–1040 (1992).

Edgar, H. et al. New Mexico decedent image database, https://doi.org/10.25827/5s8c-n515 (2020).

Yushkevich, P. et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015 (2006).

Center for Integrative Biomedical Computing, . Seg3d version: 2.5.1 (2021).

The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB version: 9.14.0 (R2023a) (2023).

Mueller, J. L. & Siltanen, S. Linear and Nonlinear Inverse Problems with Practical Applications (SIAM, 2012).

Tissue Frequency Chart; IT’IS Foundation — itis.swiss. https://itis.swiss/virtual-population/tissue-properties/database/tissue-frequency-chart/. [Accessed 21-11-2024].

Rajabi Shishvan, O. et al. ACT5 electrical impedance tomography system. IEEE Transactions on Biomed. Eng. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2023.3295771 (2023).

Santos, T. B. R. et al. Improved resolution of D-bar images of ventilation using a Schur complement property and an anatomical atlas. Med. Phys. (2022).

Kaipio, J. & Somersalo, E. Statistical and computational inverse problems Vol. 160 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2005).

Zhao, Z., Möller, K., Steinmann, D., Frerichs, I. & Guttman, J. Evaluation of an electrical impedance tomography-based global inhomogeneity index for pulmonary ventilation distribution. Intensive Care Med 35, 1900–1906 (2009).

Muller, P. et al. Estimating a regional ventilation-perfusion index. Physiol. measurement 36, 1283 (2015).

Schuster, D. P. & Haller, J. Regional pulmonary blood flow during acute pulmonary edema: a pet study. J. Appl. Physiol. 69, 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1990.69.1.353 (1990) (PMID: 2118497).

Borges, J. a. B. et al. Regional lung perfusion estimated by electrical impedance tomography in a piglet model of lung collapse. J. Appl. Physiol. 112, 225–236, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01090.2010 (2012). PMID: 21960654

Vonk-Noordegraaf, A. I. et al. Determination of stroke volume by means of electrical impedance tomography. Physiol. measurement 21, 285–293 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants and their families for agreeing to participate in this study and Allison Keck for her assistance with data collection on some of the infants. We also thank David Isaacson for a helpful discussion about the gradient calculation. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Biomedical Imaging And Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD113290. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. conceived the overall concept, supervised the direction of the project, and analyzed results. C.R., T.O. and N.R. performed computations and analyzed results. O.R.S. and G.S. analyzed data and results. K.E. and C.B. interpreted results. J.M., C.R., K.E. and C.B. wrote the manuscript. The manuscript was reviewed by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rocheleau, C.J., Overton, T.D., da Rosa, N.B. et al. Use of an anatomical atlas in real-time EIT reconstructions of ventilation and pulsatile perfusion in preterm infants. Sci Rep 15, 29622 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15543-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15543-2

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in experimental and clinical applications of chest electrical impedance tomography: a narrative review

Intensive Care Medicine Experimental (2026)

-

An improved Wexler algorithm for electrical impedance tomography using finite element method and gradient based overrelaxation

Scientific Reports (2026)