Abstract

Accurately estimating the state-of-charge (SOC) of lithium-ion batteries is of great significance for the energy management and range calculation of electric vehicles. With the development of graphics processing units, SOC estimation based on data-driven methods, especially using recurrent neural networks, has received considerable attention in recent years. However, existing data-driven methods often neglect internal resistance, which is highly detrimental to the accuracy of SOC estimation. In addition, commonly used network optimization algorithms do not always maximize the convergence speed and performance simultaneously. To solve these problems, this paper describes a battery test bench for producing an effective lithium-ion battery dataset containing current, voltage, temperature, and more importantly, internal resistance measurements. To improve the estimated SOC performance, the internal resistance is considered in the construction of a data-driven model. Using a convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM), we propose an optimization model that switches from Adam to stochastic gradient descent (SWATS). A well-known public battery dataset and an experimentally measured dataset are used to verify the feasibility of the SWATS scheme. The results show that, compared with existing data-driven methods, the proposed method is effective, especially in terms of robustness and generalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Under continued environmental pressure on the use of fossil fuels, the development of electric vehicles has received increased attention. A core component in the development of electric vehicles is the safe management of lithium-ion batteries1. The state-of-charge (SOC) represents the remaining power in a battery, providing an important indication of the remaining mileage of electric vehicles. Thus, SOC is an important state parameter for measuring the safety and reliability of electric vehicles2,3, and so the real-time and accurate estimation of SOC is of great significance.

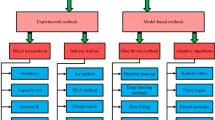

Existing methods for estimating SOC are mainly divided into the ampere-hour method4, open-circuit voltage (OCV) method5, model-based techniques6,7,8,9,10, and data-driven approaches11. Among them, data-driven approaches are the most popular because they fit the relationship between SOC and various parameters through a large amount of data, eliminating the process of battery modeling. When sufficiently extensive data are available, data-driven methods provide robust predictions of SOC under different conditions.

Following the rapid development of computer technology, artificial intelligence algorithms such as neural networks12 and deep learning13,14 have utilized the powerful parallel computing ability of graphics processing units to train models with large numbers of parameters. SOC estimation is essentially a sequential regression prediction problem. The initial state and parameters at the previous moment in time also affect SOC estimation. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have memory characteristics and enable parameter sharing, which provide unique advantages in processing time series prediction. Hence, RNNs have often been used for SOC estimations with lithium-ion batteries.

Long short-term memory (LSTM) is a kind of RNN that has a considerable advantage in dealing with sequential problems15. It also solves the issue faced by classical RNNs of the gradient vanishing or exploding in the process of reverse transmission. LSTM has been successfully applied in speech recognition and natural language processing16. A stacked bidirectional LSTM model has been developed for SOC estimation in lithium-ion batteries17, while Mamo et al.18. used LSTM with an attention mechanism for SOC estimation. Li et al.19. proposed an SOC method based on the gated recurrent unit recurrent neural network (GRU-RNN) to build a nonlinear mapping between the observable variables and SOC, and a GRU-RNN-based momentum gradient method has been developed for estimating SOC20. A Nesterov accelerated gradient algorithm based on a bidirectional GRU has also been used for SOC estimation21. To account for spatiotemporal characteristics, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are often employed due to their advantages in image processing. CNNs learn and extract the abstract visual features of the input data, and preserve the relationship between the pixels of the learned image22. Studies have proved that combining a CNN with LSTM enables the spatiotemporal relationship of sequences to be learned23,24. In addition, there have been many attempts to estimate SOC using other types of neural networks, such as backpropagation neural networks (BPNNs)25 and nonlinear autoregression with exogenous inputs (NARX)26. However, although many data-driven methods have been developed for SOC estimation in recent years, the lack of a battery test bench means that most data sources are publicly available, such as the Maryland or Stanford University datasets22,27. This has led to many constructed models being evaluated through only a single test. Additionally, internal resistance is neither included in existing datasets nor taken into account in existing data-driven approaches, even though internal resistance is strongly correlated with SOC. Furthermore, in deep neural networks, it is extremely important that the network parameters are automatically learned. Thus, the choice of optimizer is vital, and is related to the training speed and generalization performance of the model. At present, most LSTMs and their variants for SOC estimation use stochastic gradient descent with momentum (SGDM), which has high generalization performance but slow convergence speed, or the Adam optimizer, which offers fast convergence speed but poor overall convergence. As a result, it is difficult to achieve both fast optimization speed and good model generalization performance in the process of network optimization.

To overcome the above-mentioned problems, this paper proposes a CNN-LSTM-based method for SOC estimation in which the optimization process switches from Adam to SGDM (SWATS). The main contributions are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

A battery test bench is constructed to create a dataset. In the data-driven SOC estimation method, data are very important. Building a battery test bench removes the dependence on public datasets and allows abundant experimental data to be collected. The test bench can obtain current, voltage, temperature, and internal resistance measurements from various types of lithium-ion batteries at temperatures of -20–60℃ under various driving cycles.

-

(2)

A modified CNN-LSTM model with SWATS optimization is proposed for SOC estimation. The SWATS algorithm is applied to the network optimization problem of CNN-LSTM to improve the training speed and efficiency of the model. The algorithm initially uses Adam, and then switches to SGDM at the appropriate point in time. This simple hybrid strategy ensures good training speed and generalization performance. At the same time, SWATS achieves good performance under temperature changes.

-

(3)

The internal resistance of the battery is considered in the SOC estimation problem. During the discharge process, the internal resistance is closely related to the SOC, and so considering the internal resistance greatly improves the estimation performance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. "Battery test bench and dataset description" introduces the battery test bench and dataset for SOC estimation. The proposed hybrid network architecture and SWATS algorithm for SOC estimation are introduced in "SOC estimation via SWATS-based CNN-LSTM" "SOC estimation results and discussion" presents experimental results and discussion, before Sect. 5 concludes this paper.

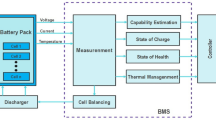

Battery test bench and dataset description

When using a data-driven method to estimate SOC, the acquisition of data is very important. Thus, a battery test bench was constructed to obtain the necessary battery measurements. All discharge processes were carried out in a temperature test chamber (ESPEC GMC-71). Batteries were discharged using a programmable electronic load (IT8818B, manufactured by ITECH). The internal resistance of the batteries was measured by a battery tester (BT3562, manufactured by HIOKI). Note that the core device in the battery test bench is the battery monitor. To solve the problem of sampling clock deviations in different instruments and equipment, preventing multiple signals from cannot be measured at the same time, a battery monitor was designed to monitor the current, voltage, internal resistance, and temperature in real time. A current sensor and temperature sensor (IN260 and TMP1117, respectively, manufactured by Texas Instruments) were used to measure the discharge current and temperature. The BT3652 battery tester was used to measure the voltage and internal resistance of the units, ensuring high accuracy and data stability. A PC terminal ensured coordination between the measuring equipment through the serial port, and the collected battery information was stored in specific files according to the requirements of the test. The test bench is shown in Fig. 1.

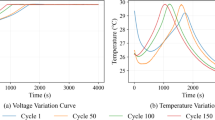

In this experiment, a Panasonic NCR18650BD battery cell was tested. The basic electrical characteristics of this battery with a rated capacity of 3000 mAh are listed in Table 1. After 20 charge–discharge cycles under a constant 2-A current, the average voltage and internal resistance characteristics were as shown in Fig. 2. Voltage is highly correlated with SOC, leading to the use of the OCV method to estimate SOC, and voltage measurements are often used as a factor in SOC estimation in data-driven approaches.

In practical applications, there is a certain correlation between the internal resistance of batteries and SOC, that is, when SOC decreases, the internal resistance steadily increases In addition, the internal resistance of batteries is usually modeled as a normal distribution with a certain variance and mean. This is because small differences in the manufacturing process, different usage environments, and long-term aging can all affect the performance of batteries, and the result of the interaction of these factors often presents a symmetrical bell shaped curve. Given the above characteristics, Pearson correlation coefficient is used to verify the correlation between internal resistance and SOC of the battery.

Furthermore, according to the correlation analysis presented in Table 2, the internal resistance of the battery also has a significant correlation with SOC, even higher than that of the voltage. The voltage of the Panasonic NCR18650BD in the process of constant discharge at 2 A is positively correlated with SOC (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.842). The internal resistance is negatively correlated with SOC (Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.960). Therefore, considering the variation of internal resistance in the data-driven method for SOC estimation should improve the accuracy and stability of the estimation.

During experimentation, the battery was exposed to four different drive cycles: New York City Cycle (NYCC), Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule (UDDS), Highway Fuel Economy Test (HWFET), and LA92 from the United States Environmental Protection Agency. The target speed driving schedules of these four drive cycles are shown in Fig. 3.

The specific steps of the test were as follows:

-

• Step 1: Fully charge the lithium-ion battery with a 2 A constant current. After a certain time, ensure that the battery’s chemical properties and voltage are stable.

-

• Step 2: Place the battery in the thermal chamber for 2 h at the set test temperature (0℃, 25℃, or 45℃).

-

• Step 3: Test profile. NYCC, UDDS, HWFET, and LA92 drive cycles were used for testing. Record the current, voltage, and internal resistance of the battery during the process.

-

• Repeat Steps 1–3.

The battery test bench was used to create a number of datasets. In addition to the current, voltage, and temperature, the internal resistance of the battery was obtained, which is of great significance for SOC estimation.

To further evaluate the accuracy and generalization performance of the proposed model, a well-recognized lithium-ion battery dataset from the University of Maryland was used as the second experimental dataset22. This dataset was collected from Samsung 18,650 LiNiMnCoO2/Graphite lithium-ion batteries by the Center for Advanced Life Cycle Engineering (CALCE). The basic electrical characteristics of the battery are listed in Table 1. The data were obtained under Dynamic Stress Test (DST), Federal Urban Driving Schedule (FUDS), and US06 drive cycles at three different ambient temperatures. Figure 4 shows the current profile and measured voltage in one discharge cycle.

Both lithium-ion battery datasets used a sampling frequency of 1 Hz for data collection, and all tests were performed at ambient temperatures of 0 °C, 25 °C, and 45 °C. Although the SWATS based CNN-LSTM proposed in this article was trained on data obtained from Panasonic NCR18650BD and Samsung INR18650 batteries, the model could also be trained on other types of battery. The well-known CALCE public dataset was used to verify the performance of the proposed model, enabling comparison with other state-of-the-art methods. The dataset collected by the battery test bench allows the generalization performance of the model to be evaluated. The experiments were conducted on a PC with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6850 K CPU @ 3.60 GHz, using Python 3.6, Tensorflow 1.13, and Keras 2.2.4.

SOC Estimation via SWATS-based CNN-LSTM

CNN-LSTM construction

LSTM is a form of RNN that was first proposed by Hochreiter et al.28. to solve the problem of gradients that are prone to long-term timing. Using memory units instead of ordinary hidden units to avoid the gradient vanishing or exploding after many time steps, LSTM overcomes the difficulties encountered in classical RNN training. The core of LSTM involves a variety of gates, including a forget gate, an input gate, and an output gate. A schematic diagram of an LSTM unit is shown in Fig. 5.

The forget gate determines what information should be discarded or retained. The input gate is used to update the unit state. The output gate determines the value of the next hidden state. The forward calculation process of an LSTM unit is as follows:

where xt, ht, and Ct are the input, output, and state of the LSTM unit, respectively. it, ft, and ot are the activation vectors of the input gate, forget gate, and output gate, respectively. W and b denote the weight matrix and bias parameter, and σ is the sigmoid activation function given by

SOC estimation is based on inference from other data, such as voltage, current, and temperature measurements. These measurements are not only continuous in time, but also have a certain spatial relationship. Thus, it is not feasible to extract their temporal relationship using only an LSTM network. Considering that CNNs can extract spatial features, this study combines CNN and LSTM to capture the spatiotemporal features of measurements in an attempt to improve the performance of the model for SOC estimation. The hidden layers are the convolutional layer, LSTM layer, and fully connected layer, respectively. In SOC estimation, the input data are the measurements of voltage, current, and temperature, and the output is the estimated SOC.

CNN-LSTM can extract complex features from multiple input variables used for SOC estimation, and can store complex irregular trends. The convolution layer receives various parameters related to SOC. In addition, features such as internal resistance and charge–discharge cycles can be extracted in the convolution layer. The vector hcnn propagates forward from the input layer to the output of the convolutional layer, and can be expressed as

where Xk is the input vector, Wcnn is the weight kernel, and bcnn is the bias.

LSTM is used to capture the time features required for SOC estimation, as extracted by the CNN. The output from the previous CNN layer is passed to the LSTM unit.

Finally, Eq. (6) is used to update the LSTM hidden state ht.

SWATS optimized algorithm

At present, the commonly used moving average algorithm, which is based on the square of the historical gradient, cannot converge to the optimal solution. Thus, the generalization error using this approach, such as in Adam, may be worse than that of SGDM and other methods. However, SGDM has disadvantages in terms of convergence speed, so the SWATS algorithm for SOC estimation is proposed. SGDM29 adds a momentum mechanism in the process of gradient descent. The gradient of the current iteration and the cumulative gradient from previous iterations affect the parameter update. In this way, SGDM prevents parameters from becoming trapped around local optima. The Adam30 optimizer has an adaptive learning rate that can be considered as a combination of the momentum method and RMSprop. Adam not only uses momentum to determine the parameter update direction, but also adjusts the learning rate adaptively. SWATS combines Adam and SGDM31. The main idea of SWATS is to allow the algorithm to switch from Adam to SGDM after a certain number of learning iterations. In this way, the convergence speed of the model is accelerated while convergence to the optimal solution is ensured. The optimization strategy of SWATS is shown in Fig. 6.

In this hybrid strategy, the switchover point and the learning rate for SGD after the switch are important parameters, and can be learned as part of the training process. Note that Keskar’s model31 monitors the SGD learning rate after the switchover using a projection of the Adam step on the gradient subspace and takes the exponential average as an estimate. Further, the switchover is triggered when no change in this monitored quantity is detected. The update equation of SGDM is given by:

where f is a loss function, wk denotes the kth iteration, αk is the learning rate, and \(\hat {\nabla }f(wk)\) denotes the stochastic gradient computed at wk. β∈[0, 1) is the momentum parameter. The update equation of Adam can be written as:

Consider wk with a stochastic gradient gk and a step pk computed by Adam. Then, gk and pk can be expressed as:

The process for calculating the switchover point and the learning rate for SGD after the switch is described in Algorithm 1.

The determination of the switchover point and the learning rate can also be established by other criteria, such as\(\gamma k=\frac{{\left\| p \right\|}}{{\left\| g \right\|}}\), involving the monitoring of gradient norms. Regarding the selection of the learning rate and switchover point, more specific derivations can be found in31.

SOC Estimation based on the proposed method

As shown in Fig. 7, the proposed SWATS-based CNN-LSTM network starts with a sequence input layer. The input vectors are some measured signals of the battery, i.e., temperature, current, voltage, and resistance: x=[T, I, V, R], T=[t1, t2,…, tn], I=[i1, i2,…, in], V=[v1, v2,…, vn], R=[r1, r2,…, rn]. Next, perform data preprocessing. In this paper, we use the minimum-maximum normalization method to preprocess the data, and scale the battery data to 0 ~ 1 range, to remove the unit limit of the data, so as to facilitate the comparison and weighting of indicators in different units or magnitudes and improve the training speed of the network. Minimum-maximum normalization:

A convolution layer then learns the spatial features based on previous inputs. The output of the convolution layer serves as the input to the LSTM layer, and the memory unit effectively retains or eliminates the influence factors according to historical training, thus learning the temporal features of the measured signals. The fully connected layer maps all distributed features to the sample label space, and merges the output. Finally, an output layer gives the SOC estimation: ŷ=SOC=[soc1, soc2,…, socn]. One-dimensional convolution is used to extract the features of the measurements. The convolution layer uses eight filters of length three to apply the convolution operation to the input multivariate time-series, and passes the result to the LSTM layer. The batch size and time steps of LSTM are set to 64 and 50, respectively. The SWATS-based CNN-LSTM for SOC estimation uses the backpropagation method. Considering possible overfitting during the training phase, the dropout algorithm with a dropout percentage of 30% is used in each hidden layer. To obtain superior training outcomes, the optimization function of the network is SWATS as mentioned above.

The root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) are used to evaluate the performance of the established model. RMSE measures the deviation between the prediction and the measurement, while MAE indicates the degree of fit between the prediction and the measurement. If ym denotes the measurement and ŷm denotes the prediction, and M denotes the number of samples, then

Model complexity and deployment feasibility analysis

The proposed method builds upon traditional CNN-LSTM architectures but introduces SWATS to reduce computational demands while maintaining high SOC estimation accuracy. From a complexity perspective, the optimized model significantly reduces both parameters and floating-point operations (FLOPs). Specifically, parameter count decreases by approximately 25% (from 35,000 to 26,250), and FLOPs reduction is around 40% (from 128 million to 76.8 million). This reduction in computational load enables the model to run efficiently on resource-constrained embedded devices, enhancing its practicality for real-world applications.

To validate the method’s real-time performance capabilities, experiments were conducted under standard testing conditions. The results demonstrate that the optimized CNN-LSTM model achieves an average inference time of 0.15 s per SOC estimation (± 0.03 s), outperforming both traditional LSTM-based approaches (0.28 s, ± 0.04 s) and DCNN variants (0.21 s, ± 0.02 s). This significant improvement in speed ensures the model’s suitability for applications requiring rapid responses.

Furthermore, this method supports hardware acceleration strategies such as integrated FPGA implementation, further enhancing the practicality of the model. For instance, inference speed improves to 0.10 s per SOC estimation (± 0.02 s) when deployed on FPGA platforms, accompanied by a 35% reduction in energy consumption. This combination of efficiency and reduced hardware costs makes the proposed method highly viable for industrial deployment.

SOC Estimation results and discussion

Complete Estimation of SOC during charging and discharging process

Figure 8 shows the SOC estimation for the FUDS test at room temperature. The SWATS-based CNN-LSTM network with 150 hidden neurons was trained over 500 epochs using data from the US06 and DST tests at 25℃. Figure 8 describes the complete SOC estimation of a lithium-ion battery during the charging and discharging process, and the error represents the distance between the estimated SOC and the measured SOC. The overall performance of the SWATS-based model is satisfactory. After a short period of fluctuation in the charging process and the early stage of discharge, high estimation accuracy is achieved (maximum error ~ 4%). In the later stage of the discharge process, the error increases, but it can still be controlled within 5%.

The prediction of the FUDS condition starts from the time of charging, and the values of RMSE = 0.019 and MAE = 0.013 indicate that the proposed model can achieve good performance in different service periods. The results show that, under a fixed temperature and mixed drive cycles, FUDS produces a stable prediction performance with an RMSE of less than 0.024.

Comparison of SWATS based CNN-LSTMs at varying epochs

In a neural network, an epoch refers to the process of updating the parameters after all training data have undergone a forward and a backward process. Various numbers of epochs were used to evaluate the impact of epochs on the estimation performance of the SWATS-based model. The DST and US06 datasets at room temperature were used as training sets. Table 3 lists the comparison results for 300, 400, and 500 epochs, tested on the FUDS datasets recorded at an ambient temperature of 25℃. Each of the layers in three networks consisted of 500 computational nodes. As the number of epochs increases, the accuracy of the model improves, but the rate of improvement obviously becomes weaker. Figure 9 shows the estimation results of the established SWATS-based model tested on the FUDS dataset. The estimation accuracy increases slowly as the number of epochs increases from 400 to 500. Too many epochs in the training process will increase the computational load with little effect on the accuracy. On the contrary, if there are too few epochs, it is difficult for the model to learn the dynamic characteristics of lithium-ion batteries. Therefore, the number of epochs needs to be determined according to the dataset. The results obtained in this study suggest that 500 epochs is the optimal number.

Note that larger errors usually occur in the middle and at the end of the discharge process. This is because the voltage is stable in the middle of the discharge process, and small voltage fluctuations may lead to larger SOC prediction errors. At the end of the discharge, the battery power is low, resulting in changes in the internal characteristics of the battery that are difficult to estimate.

Comparison of SWATS-based CNN-LSTM with LSTM and CNN-LSTM

To further verify the effectiveness of the SWATS-based model, we compared it with conventional LSTM and CNN-LSTM models. The comparison results using FUDS as a test case are shown in Fig. 10. The discharge process was simulated under various initial SOC conditions. This is because, in actual estimation cases, the battery does not always start discharging from 100%. In this experiment, the initial SOC was set to either 80%, 60%, or 40% to verify the robustness of the model under different initial conditions. The prediction results are compared in Fig. 10, and the RMSE and MAE are listed in Table 4.

It is clear that all three models can predict SOC, although the proposed SWATS-based model outperforms the LSTM and CNN-LSTM models. According to Table 4, the proposed method has the highest estimation accuracy under all initial conditions. As the initial SOC decreases, the difficulty of estimation increases. This is because as the initial SOC decreases, the amount of data used for network training and testing is greatly decreases, making it difficult to capture the spatiotemporal relationship of sequences. In addition, in the middle and late stage of discharge process, the chemical characteristics of the battery become complexly, and the factors affecting SOC estimation become more obvious, which increases the difficulty of estimation. But as the model improved, the proposed model retains good estimation accuracy.

SOC Estimation at varying ambient temperatures

SOC estimation becomes more difficult at low temperatures, and so the influence of the ambient temperature cannot be ignored. To evaluate the sensitivity of the model to temperature, US06 was used as the training set, and the FUDS dataset at various temperatures was used as the test case to verify the proposed method. The estimation results of complete charge/discharge under the FUDS conditions are shown in Fig. 11. Due to the temperature variation, the estimation of SOC presents a nonlinear and unstable trend. At low temperatures, although the classic LSTM and SWATS-based models can estimate SOC well for the lithium-ion battery, the estimation error is relatively large compared with higher ambient temperatures, and the predicted SOC fluctuates significantly over the entire estimation process. As the temperature decreases, the estimation error tends to increase. Due to the embedded LSTM memories, both LSTM and SWATS-based CNN-LSTM achieve low estimation errors over the time series, but the addition of a convolutional layer improves the ability to capture spatial characteristics such as temperature. To verify the generalization performance of the model, the DST test set was used and shown in Fig. 12.

The fluctuations in the predictions made by the proposed SWATS-based method are much smaller than those of the simple LSTM, which indicates that the proposed method is less sensitive to temperature. At 0℃, the maximum error is greater than 10%, but most of the errors are still less than 5%. At low ambient temperatures, the internal chemical characteristics inside the battery vary greatly, making them more difficult to capture. As shown in Table 5, the proposed model outperforms LSTM in terms of MAE at all temperatures, and produces better RMSE performance at 25 °C and 0 °C. At high temperature, the chemical properties of the battery are stable, the relationship between SOC and measurements are easier to capture, and the RMSE of the two models is quite different.

SOC Estimation for Panasonic NCR 18650BD (considering internal resistance)

Different from the public dataset, the lithium-ion battery dataset constructed using the battery test bench not only contains the current, voltage, and temperature of the battery, but most importantly it also contains internal resistance measurements. As the estimated performance of the SOC and the internal resistance are closely related, these data are very meaningful.

Figure 13 shows the SOC estimations for the Panasonic NCR 18650BD battery. In this experiment, the training case was a mixture of NYCC, UDDS, and HWFET, and the test case was LA92 at an ambient temperature of 25℃. The red curve in the figure indicates the estimations using only current, voltage, and temperature data. The blue curve denotes the estimations including the internal resistance data. The experimental results show that when the lithium-ion battery dataset is changed, it is difficult to capture the regular SOC due to external interference and noise in the battery test platform. This reduces the estimation performance of the model. However, considering the influence of internal resistance in the SOC estimation greatly improves the accuracy of estimation. Thus, the proposed SWATS-based network can still obtain accurate SOC estimations. The model with internal resistance taken into account provides significantly better SOC estimations during the entire discharge process than the traditional method that only considers current, voltage, and temperature, and the estimated and the measured results display a high degree of correlation. This experiment verifies the generalization performance of the proposed model. Table 6 describes the effect of the internal resistance data on the model performance. According to Table 6, under the LA92 conditions, the consideration of internal resistance reduces the MAE and RMSE significantly. Among them, MAE decreased by 52.8%, RMSE decreased by 47.6%, and maximum error decreased by 4% This strongly validates the effectiveness of increasing consideration of battery internal resistance when using this method for SOC estimation.

we use a statistical test to verify whether this improvement is statistically significant, it can strength claims about superiority over baseline methods. Paired t-test is a commonly used statistical methods for comparing the differences between two sets of related data to analyze paired designs (i.e. measuring the same group of subjects under two different conditions). The mathematical formula is as flows:

Where \(\overline {D}\) is the mean of the difference, \({S_D}\) is the standard deviation of the difference, and n is the number of samples After calculation, the sample rejected the null hypothesis, P = 0.0075, This indicates a significant difference between the two sets of data, verifying the effectiveness of considering battery internal resistance in SOC estimation problems.

To fully verify the effectiveness of internal resistance for SOC estimation of lithium-ion batteries, the Panasonic NCR 18650bd dataset was tested using different data-driven models: LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM, SWATS-LSTM, GRU, CNN-GRU, Bi-GRU, SWATS-GRU, NARX, and NARX-LSTM. The RMSE results of these ten models with two different inputs (with and without internal resistance data) are shown in Fig. 14. As the internal resistance of the battery is closely related to SOC, it should not be ignored in SOC estimation, especially when using data-driven methods. Compared with the traditional estimation models considering only the current, voltage, and temperature, the RMSEs of the models considering the battery’s internal resistance under the LA92 conditions have been reduced by nearly 50%. This further verifies the benefits of the battery test bench established in this study, as it can produce rich and meaningful battery datasets for different types of lithium-ion batteries and temperatures.

Comparison of SWATS-CNN-LSTM with SGD-CNN-LSTM and ADAM-CNN-LSTM

Finally, SGDM, Adam, and SWATS were used to train the CNN-LSTM architecture on the Samsung 18,650 LiNiMnCoO2/Graphite lithium-ion battery dataset. The training loss and validation loss of the model are shown in Fig. 15. SGDM-CNN-LSTM finally achieved the best test accuracy during training. After 1000 epochs, the training loss stabilized at 0.037, although the validation loss jittered significantly with each epoch. Adam-CNN-LSTM produced the fastest rate of decrease in the training loss, but although the training and generalization metrics of Adam are initially better than those of SGDM, the convergence stagnates and the training loss remains stuck at 0.074. SWATS uses a simple strategy to convert from Adam to SGD during training. It achieves a rapid initial decrease in the training loss, and then converges well after switching to SGDM, with an eventual loss of 0.041. This experiment demonstrates that SWATS combines the advantages of Adam and SGDM, and switches from Adam to SGDM at the appropriate point. Overall, this improves the training speed of the CNN-LSTM and guarantees good generalization and convergence.

Conclusions

This study has made three special contributions. The first is the establishment of a battery test bench, free of dependence on public datasets, which provides the ability to create datasets for various types of lithium-ion batteries at different temperatures and driving cycles. More importantly, in addition to the conventional current, voltage, and temperature data, the measurements also include internal resistance. The second contribution is a data-driven method that considers internal resistance for SOC estimation. By considering internal resistance, the RMSE of the model can be reduced by nearly half. The third contribution is the creation of a CNN-LSTM model that uses a SWATS optimization strategy. The CNN-LSTM network structure learns the spatiotemporal information of the battery measurement sequence, and better captures the spatiotemporal dependences. SWATS switches from Adam to SGDM at a specific switching point, which improves the generalization performance and training speed of the model.

Finally, two different lithium-ion battery datasets were used for simulations, and the effects of the ambient temperature, network parameters, network structure, and optimization algorithms for SOC estimation were analyzed through experiments. The results show that the proposed model has good robustness to temperature changes, and the addition of internal resistance data greatly increases the accuracy of the estimation model. In summary, the SWATS-based CNN-LSTM model considering internal resistance has the advantages of high network generalization performance and high SOC estimation accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Babu, P. S. & Indragandhi, V. Enhanced SOC Estimation of lithium ion batteries with realtime data using machine learning algorithms. Scientific Reports 14, (2024).

Li, F., Zuo, W., Zhou, K., Li, Q. & Huang, Y. State of charge Estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on PSO-TCN-Attention neural network. J. Energy Storage. 84, 110806 (2024).

Zhao, F. M., Gao, D. X., Cheng, Y. M. & Yang, Q. Application of state of health Estimation and remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries based on AT-CNN-BiLSTM. Sci. Rep. 14, 29026 (2024).

Ng, K. S., Moo, C. S., Chen, Y. P. & Hsieh, Y. C. Enhanced coulomb counting method for estimating state-of-charge and state-of-health of lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy. 86, 1506–1511 (2009).

He, H., Zhang, X., Xiong, R., Xu, Y. & Guo, H. Online model-based Estimation of state-of-charge and open-circuit voltage of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Energy 39, 310–318 (2012).

Li, F. et al. State-of-charge Estimation of lithium-ion battery based on second order resistor-capacitance circuit-PSO-TCN model. Energy 289, 130025 (2024).

Yu, Q., Huang, Y., Tang, A., Wang, C. & Shen, W. OCV-SOC-temperature relationship construction and state of charge Estimation for a series–parallel lithium-ion battery pack. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24, 6362–6371 (2023).

Hussein, H. M., Aghmadi, A., Abdelrahman, M. S., Rafin, S. S. H. & Mohammed, O. A review of battery state of charge Estimation and management systems: models and future prospective. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy Environ. 13, e507 (2024).

Knox, J., Blyth, M. & Hales, A. Advancing state Estimation for lithium-ion batteries with hysteresis through systematic extended Kalman filter tuning. Sci. Rep. 14, 12472 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. SOC Estimation of lead–carbon battery based on GA-MIUKF algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14, 3347 (2024).

Babu, P. S., V, I. & Enhanced SOC Estimation of lithium ion batteries with realtime data using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 14, 16036 (2024).

Zhao, F. M., Gao, D. X., Cheng, Y. M. & Yang, Q. Estimation of lithium-ion battery health state using MHATTCN network with multi-health indicators inputs. Sci. Rep. 14, 18391 (2024).

Jafari, S. & Byun, Y. C. Efficient state of charge Estimation in electric vehicles batteries based on the extra tree regressor: A data-driven approach. Heliyon 10, (2024).

Tang, A. et al. A novel lithium-ion battery state of charge Estimation method based on the fusion of neural network and equivalent circuit models. Appl. Energy. 348, 121578 (2023).

Tang, P., Hua, J., Wang, P., Qu, Z. & Jiang, M. Prediction of lithium-ion battery SOC based on the fusion of MHA and ConvolGRU. Sci. Rep. 13, 16543 (2023).

Ghaeminezhad, N., Ouyang, Q., Wei, J., Xue, Y. & Wang, Z. Review on state of charge Estimation techniques of lithium-ion batteries: A control-oriented approach. J. Energy Storage. 72, 108707 (2023).

Bian, C., He, H. & Yang, S. Stacked bidirectional long short-term memory networks for state-of-charge Estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Energy 191, 116538 (2020).

Mamo, T. & Wang, F. K. Long short-term memory with attention mechanism for state of charge Estimation of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Access. 8, 94140–94151 (2020).

Li, C., Xiao, F. & Fan, Y. An approach to state of charge Estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on recurrent neural networks with gated recurrent unit. Energies 12, 1592 (2019).

Jiao, M., Wang, D. & Qiu, J. A GRU-RNN based momentum optimized algorithm for SOC Estimation. J. Power Sources. 459, 228051 (2020).

Tan, C. M., Yang, Y., Kumar, K. J. M., Mishra, D. D. & Liu, T. Y. Addressing practical challenges of lib cells in their pack applications. Sci. Rep. 14, 10126 (2024).

Khan, M. K. et al. Efficient state of charge Estimation of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles using evolutionary intelligence-assisted GLA–CNN–Bi-LSTM deep learning model. Heliyon 10, (2024).

Hou, J., Xu, J., Lin, C., Jiang, D. & Mei, X. State of charge Estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on battery model and data-driven fusion method. Energy 290, 130056 (2024).

Kanouni, B., Badoud, A. E., Mekhilef, S., Bajaj, M. & Zaitsev, I. Advanced efficient energy management strategy based on state machine control for multi-sources PV-PEMFC-batteries system. Sci. Rep. 14, 7996 (2024).

Yang, F. et al. Novel joint algorithm for state-of-charge Estimation of rechargeable batteries based on the back propagation neural network combining ultrasonic inspection method. Journal Energy Storage 99, (2024).

Takyi-Aninakwa, P., Wang, S., Zhang, H., **ao, Y. & Fernandez, C. A NARX network optimized with an adaptive weighted square-root Cubature Kalman filter for the dynamic state of charge Estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Journal Energy Storage 68, (2023).

Nascimento, R. G., Viana, F. A., Corbetta, M. & Kulkarni, C. S. A framework for Li-ion battery prognosis based on hybrid bayesian physics-informed neural networks. Sci. Rep. 13, 13856 (2023).

Schmidhuber, J. & Hochreiter, S. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Sutskever, I., Martens, J., Dahl, G. & Hinton, G. On the importance of initialization and momentum in deep learning. In International conference on machine learning. 1139–1147 (2013).

Kingma, D. P. & Adam A method for stochastic optimization. Preprint Arxiv :14126980. (2014).

Keskar, N. S. & Socher, R. Improving generalization performance by switching from Adam to Sgd. Preprint Arxiv :171207628. (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62227802), the Central Guiding Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects of China under Grant 2023ZY1008, the Science and Technology Planning Project of Shijiazhuang (231130311) and the Doctoral Research Foundation for Shijiazhuang University (24BS017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z., C.L. and T.W. made the numerical simulations and experimental study. T.L. and Y.C. wrote the main manuscript text. P.Z. prepared (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14). All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Liu, C., Li, T. et al. CNN-LSTM optimized with SWATS for accurate state-of-charge estimation in lithium-ion batteries considering internal resistance. Sci Rep 15, 29572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15597-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15597-2