Abstract

Application of hybrid low salinity water and polymer flooding (LSPF) as an enhanced oil recovery (EOR) method takes advantage from the wettability alteration by low salinity water and enhancement of mobility ratio by addition of polymer. Recently it is shown that polymer affects the possible interactions in oil/brine/rock system e.g., interfacial tension, contact angle, pH and zeta potentials. However, in the case of highly heterogeneous systems such as fractured porous media, the present understanding of the effect of LSPF on pore scale displacing mechanisms and enhanced oil recovery is very limited compared to the low salinity water. With this aim, in the present study, a series of injection scenarios were performed in fractured micromodels. Different experiments were conducted to illustrate the effects of brine composition, addition of HPAM to brine solution and injection scenario (either secondary or tertiary) on pore scale displacement mechanisms, sweep efficiency and oil recovery. Sea water (SW) and twice concentrated SW (2xcSW) and 10 times diluted SW (10xdSW) as well as 1000ppm HPAM (based on the previously study on the optimum oil/brine and rock/brine interactions) were considered. The results showed that in the case of secondary injection and absence of HPAM, the difference between the recovery factors of different brines is minimal and none of them are capable of producing the oil from the matrix. In the secondary injection scenario, combination of 2xcSW and polymer didn’t improve the oil recovery considerably, but the success of the hybrid process in the cases with lower salinity (i.e., SW and 10xdSW) was remarkable. For tertiary injection, adding HPAM to the formerly injected brine (which was injected in the secondary model) improved the EOR considerably. The amount of improvement was significantly larger in the case of brines with lower salinities. For all the investigated hybrid cases, the ultimate oil recovery after tertiary injection scenario was larger than secondary counterparts. The results are discussed based on the possible interactions in the oil/brine/rock system, rheological properties and visualized displacing mechanisms in the case of each investigated injectant and injection scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Produced oil from an oil reservoir using just its initial pressure is not significant. In order to preserve the reservoir pressure and enhance the oil recovery, water flooding is commonly implemented as a key technique1,2. Jadhunandan and Morrow (1995) indicated that performance of waterflooding has strong reliance on different factors such as wettability of the porous media and the compositions of the encountered brines3. These findings were inspiring for scientists to manipulate the composition and salinity of injected brine4,5. It is proven that low salinity water flooding (LSWF) and adjusted composition water injection are able to increase oil recovery in both sandstone6 and carbonate7 reservoirs.

In recent years many researchers have focused on understanding the involved fluid/fluid and fluid/rock interactions to shed light on the dominating mechanisms of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) by LSWF8. Most of the researches on LSWF are focused on the impact of concentration of potential determining ions (PDI) such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ on the wettability alteration of the rock surface9. These divalent ions can act as bridges to connect the polar compounds of oil to the negatively charged surface of sandstones. By reducing the salinity of water, and the consequent detachment of these positive ions (to compensate their diluted amount in the brine), some of these bonds break and thus negative polar compounds of oil would release10, which in turn cause the wettability alteration of the rock surface from oil-wet towards water-wet.

The ineffectiveness of LSWF is very severe in highly heterogeneous reservoir rocks i.e., fractured systems11. Mahmoudzadeh et al., (2022) compared the enhanced oil recovery (EOR) capability of formation water, seawater and diluted seawater on oil recovery in four different fractured micromodels12. The results proved that LSWF was not adequately capable of oil recovery from single matrix (under either counter current or co-current conditions). Hybrid methods using chemicals can achieve dramatic improvements in the EOR in such highly heterogeneous porous media13,14,15,16. One of the chemicals which have been used commonly along with waterflooding is polymer. Polymer increases the viscosity of injected brine and so reduces its mobility17, and as a result, sweep efficiency and oil recovery increases18.

As one step further, scholars have demonstrated that the combination of LSWF and polymer flooding has positive effects on oil recovery19. However the ionic composition of reservoir brine and injection brine influences on the process performance10,20. As the ionic strength of brine increases, the effect of polymer on viscosity decreases21. Divalent ions (Mg2+ and Ca2+) in the brine are absorbed on negatively charged carboxylic groups of the backbones of HPAM (Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide). In such a case, the expansion of polymer chains reduces and solution loses the viscosity22,23.

Vermolen et al., (2014) injected brines with different salinities (reservoir brine and its 2, 4, 10 times diluted counterparts) into various sandstone core plugs24. They proved that with increasing the salinity, degradation increases and viscosity decreases. Based on their results the viscosity of low salinity brine (1500ppm TDS) with 1000ppm HPAM was as much as the viscosity of reservoir brine (260000 ppm) with 3900ppm HPAM. Several core flood experiments also were performed by Kozaki et al., (2012) on Berea sandstone in order to evaluate the effect salinity (33793ppm and 1000ppm TDS) of the polymer solution on oil recovery factor25. They reported 10% reduction in the residual oil saturation by using tertiary mode of this low salinity polymer solution. Almansour et al. (2017) conducted core flooding experiments with Bentheimer and Berea sandstone cores to study the effect of rock type, salinity (197451 ppm and 3360ppm TDS) and presence of HPAM (5000 ppm) on the oil recovery factor26. They indicated that in Berea sandstone, recovery factor in secondary low salinity and tertiary low salinity polymer flooding (LSPF) scenario was higher than secondary high salinity (HS) followed by tertiary HS with polymer injection. While for Bentheimer sandstones the results of oil recovery at high and low salinity injection scenarios were close to each other. Generally, ultimate oil recovery factor in Berea sandstone was considerably less than Bentheimer sandstone, and results were attributed to their initial wettability (contact angle of brine with different salinity level (formation brine and sea water) was 70° for Bentheimer while for the Berea sandstone this was 90°).

The synergistic effect of low salinity water and polymer was also confirmed through sandstone core flooding tests27. They investigated the effectiveness of LSPF after extended waterflooding (either of HS water (27500 ppm) and LS water (2498 ppm)) as well as high salinity polymer flooding (HSPF). To increase the viscosity of low salinity water, 1400ppm HPAM was added into the solution. To reach the same viscosity in HS water, 2300 ppm HPAM was added into injection brine. Their results showed 8.0 to 10% incremental oil recovery by injection of LSPF after extended waterflooding or HSPF. Viscoelasticity effect of the polymer solution was proposed as the main contributing factor in increasing oil recovery.

Sedaghat et al. (2013) micromodel experiments with different HPAM solutions (300, 600, 900 and 1200ppm in the absence of salinity) showed that addition of HPAM to the injection brine after secondary water flooding increases oil recovery28. Also, their results showed that with increasing HPAM concentration oil recovery increases. Algharib et al. (2014) performed a series of flooding experiments in sandstone cores29. A preflush slug of 0.05 PV (pore volume) of formation water (30,000ppm TDS) was followed by 0.2 PV of polymer solution, which in turn was displaced by formation water. The oil recovery achieved by this intermittent injection scenario was 86%, while in continuous polymer flooding mode oil recovery was 70%. They also showed that oil recovery factor increases by increasing the concentration of polymer, which was attributed to the viscosity effect.

Emamimeybodi et al. (2008) evaluated the effect of the heterogeneity of reservoirs on polymer flooding by using quarter five spot glass micromodels30. They indicated that due to viscosity effect, the recovery factor of polymer flooding (300 ppm HPAM) in both homogenous and heterogeneous porous media was higher than waterflooding (20000ppm TDS). Yousefvand and Jafari (2015) studied the oil recovery in a glass micromodel after low salinity water flooding (30000ppm) and polymer flooding (8000 ppm HPAM). The ultimate recovery for LSWF and polymer flooding were reported 16.63% and 26.32% respectively. Higher viscosity of the polymer solution was proposed as the main reason for the additional recovery31.

Based on the above literature in most cases the better performance of the LSPF is attributed to the viscosity effects. There are extensive studies which have separately investigated the possible effect of polymer on the viscosity. Cancela et al. (2022) measured the viscosity of HPAM solutions at different concentrations (1000, 2000 and 3000ppm) in a brine with TDS of 1600ppm for different shear rates32. At concentration of 1000ppm HPAM, with increasing the shear rate, the viscosity decreased (5.3, 4.1 and 3.7 cp. for shear rate of 50, 125, and 200 s− 1 respectively). Almansour et al., (2017) measured the viscosity of 5000ppm HPAM in 10 times diluted seawater (TDS of 3360 ppm) at 60℃. They observed viscosity decreased from 100cp to approximately 60cp with increasing the shear rate from 8 to 90s− 1 which shows shear thinning behavior of polymer26. Baek et al. (2020) measured the viscosity of HPAM solution with and without surfactant at different shear rates33. The HPAM concentration was 5400ppm in brine with TDS of 56,456 ppm. The viscosity of HPAM was nearly 150 cp. at shear rate of 1s− 1 and it decreased to 18cp at shear rate of 100s− 1 while in the brine solution with HPAM and 5000ppm surfactant (phenol-7PO-15EO) the viscosity was stable at around 200cp from shear rate of 0.05 to 0.8s− 1. From shear rate of 0.9− 1 the viscosity started decreasing and at higher values it overlapped HPAM solution graph and showed the same results.

Effect of HPAM concentration on shear viscosity was investigated by Jung et al., (2013). HPAM at different concentrations (1500, 3000, 5000 and 8000ppm) was dissolved in 5000ppm NaOH solution34. At high HPAM concentrations (8000 and 5000ppm) the viscosity was 1200 cp. and 700 cp. respectively at shear rate of 2s− 1 while at concentrations of 3000 and 1500 ppm the viscosity was 300 and 30cp at the same shear rate. The ultimate viscosity for different HPAM concentrations (1500, 3000, 5000 and 8000ppm) at shear rate of 300s− 1 was 80, 40, 10 and 5 cp. respectively. They reported that at all HPAM concentrations with increasing the shear rate, viscosity decreased and due to uncoiling and aligning of polymer chains at high shear rates, viscosity showed shear thinning behavior. In another test they measured the viscosity of HPAM at concentration of 1500ppm at different salinity levels of NaCl (0, 10000, 30000 and 50000ppm). The highest amount of viscosity belonged to HPAM solution without salinity which was 400cp at shear rate of 2s− 1 and 20cp at shear rate of 300s− 1.

Another rheological study was performed by Unsal et al. (2018). The polymer concentration in the higher salinity solution (TDS of 6230ppm) was 3100 ppm, while the lower salinity solution (TDS of 623ppm) contained 1400 ppm35. They reported that both brine solutions exhibited shear thinning rheology. Also, at shear rates of less than 5s− 1 the viscosity of the LSP (low salinity polymer) solution was higher than the HSP (high salinity polymer) solution. At shear rates of higher than 5s− 1, the viscosity of the LSP was lower than the HSP solution, because at high shear rates polymer coil-stretch transition occurs.

Abdullahi et al., (2022) investigated rheological behavior of the HPAM solution at different concentrations (i.e., 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000 and 5000ppm) in deionized water36. At low shear rate (10s− 1) the highest (1000 cp.) and lowest (110 cp.) amounts of viscosity belonged to 5000ppm and 1000ppm HPAM solutions, respectively. The same trend was observed at shear rate of 1000s− 1 with viscosity of 50 and 8cp respectively. They attributed their observations to the higher degree of intermolecular entanglement. In fact, molecular chain interactions are function of HPAM concentration and at high HPAM concentrations, greater molecular interactions between chain networks occur; therefore, viscosity enhances. Also, Abdullahi et al., (2022) conducted another test to evaluate the effect of types of ions in HPAM solutions (concentration of HPAM was 2000ppm and TDS of both brines was 30000ppm but one of the solutions just contained NaCl and the other one was a combination of different salts, i.e., MgCl2, CaCl2 and NaCl). At all shear rates the viscosity of brine with different salts was less than the HPAM solution with just NaCl. It was concluded that cations neutralize or shield the negative charges of HPAM. Moreover, the ionic strength of divalent ions (Ca2+ and Mg2+) are greater than monovalent ions such as Na+. The ionic strength directly affects viscosity degradation of HPAM molecules by shrinking the HPAM chain electrical double layer.

Based on the above extensive literature, in most cases, the main dominating mechanism of the enhanced oil recovery by LSPF is attributed to the viscosifying capability of the polymers. However these researches have not investigated the detailed rheological behavior of aqueous phases in the presence of polymer. Although there are some other researches which have investigated the effect of polymer on the viscosity of the aqueous phase, they do not consider the possible effect of rheology on the oil recovery. In addition, in most of the researches, other possible interactions in oil/brine/rock system (such as IFT between oil and brine, wettability) and their effect on the synergy of low salinity water and polymer are overlooked. As a result, the effect of such interactions on the displacing mechanisms of the oil by LSPF are not investigated. In addition, although some researches considered the permeability variations in the porous media, highly heterogeneous porous media such as those in fractured reservoirs are not well investigated and the involved recovery mechanisms from them are not understood yet. Limited studies in fractured models are limited to dual-permeability models where both fracture and matrix are contributing in the production. More realistic and representative fractured models, i.e., double-porosity single-permeability systems, in which both injection and production of the fluids should happen through the fracture media (and as a result any production from matrix should happen through the interaction with fracture) are overlooked. With this aim, the application of hybrid low salinity and polymer flooding in single permeability fractured porous media is investigated in the present study. Brines with three different levels of salinity were prepared, with (1000ppm concentration) and without polymer and were injected through designed fractured micromodel. In addition, different injection scenarios (secondary vs. tertiary) are implemented. The predominant effective displacement and recovery mechanisms, as well as the amount of the recovered oil are evaluated. To further investigate the results, pH, IFT, contact angle and rheological tests were performed.

Materials and methodology

Materials

Crude oil

The physical properties of the used crude oil sample (from an oil field in south western of Iran) are presented in Table 1.

Brine samples

The sea water (SW) composition used in this study was formulated based on Persian Gulf seawater, as reported by Farhadi et al. (2021)37, which is presented in Table 2. To prepare the brines, the required amounts of salts were accurately weighed and dissolved in distilled water to obtain clear and homogeneous solutions. Additional brines, i.e. 10 times diluted SW (10×dSW) and 2 times concentrated SW (2×cSW), were prepared using the same salt components, with concentrations adjusted based on the desired brine composition.

Polymer solutions

To prepare desired polymer solutions, 1000ppm of HPAM (Fig. 1, molecular weight: 8 million Da; hydrolysis degree: 20–30%) was added to the chosen brine and then it was slowly stirred by the magnetic stirrer in 600 rpm for one hour.

The reason of choosing this amount of HPAM is based on the presented results of Amiri et al. (2022)38. They investigated the effect of brine with different salinities (sea water (SW) and its two different dilutions, i.e. twice concentrated (2xcSW) and 10 times diluted (10xdSW)) along with different concentrations of HPAM as polymer, i.e. 250, 500, 1000 and 2000 ppm, on contact angle of oil droplets on quartz surface in the presence of aqueous phases. The initial contact angle of the surfaces after aging in crude oil was 175°, which showed strong oil-wet state. In the absence of the HPAM, the largest contact angle changes observed in the case of 10xdSW (50°). In the case of 10xdSW, the highest degree of wettability alteration was observed for 1000 ppm HPAM (85°) and with further increasing the polymer concentration to 2000 ppm the final contact angle was higher than the case of 1000 ppm counterpart, which showed the detrimental effect of using too much HPAM on the wettability alteration. Similar results were reported in the case of other two salinities (i.e., SW and 2xcSW) in which 1000 ppm HPAM was the optimum concentration for wettability alteration.

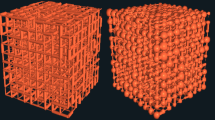

Glass micromodel

Based on the CT scan images of a core thin section, two-dimensional pattern of the porous medium (12 cm × 2 cm) was designed using Corel Draw software and then, it was engraved on the glass (4 mm thickness) through a laser machine. In the next stage, the engraved glass plate, was fused to the similar plain glass in the furnace, at 700℃.

Figure 2 show the designed pattern of micro-model. The injection and production are just via fracture and any production from the matrix shall happen through its interaction with this fracture. The properties of the designed micro-model are listed in Table 3.

Methodology

pH measurement

pH of different brine samples (SW, 10xdSW, 2xcSW) without and with 1000ppm of HPAM are measured using AZ-86,555 pH meter at ambient temperature. For this purpose, 20 cm3 of each brine sample was required and the pH was monitored until reaching a constant value.

Rheological test

The rheological behavior of the aqueous phase was determined using a rotational rheometer with concentric cylindrical device (Anton Paar, MCR 302, Fig. 3). For different brines without and with polymer (at 1000ppm HPAM), shear stress was measured versus shear rate (in the range of 1 to 1000 s− 1).

IFT and contact angle measurements

The interfacial tension between crude oil and brine was measured using the Wilhelmy plate method (Fig. 4a) with a Krüss K100C Force Tensiometer (Fig. 4b). To do this at first, the Wilhelmy plate was completely immersed in the liquid of the lighter phase which is oil in this study and tared the balance in this state. The vessel with the lighter liquid was then removed from the sample table. In the second step, to form the interfacial lamella, the plate was immersed in a vessel containing the heavier liquid which is brine in this study. Then oil was carefully poured into the existing container with water and the Wilhelmy plate is pulled back up to the interface.

Sesile drop method (Fig. 5) is used for wettability determination throgh contact angle measurement of the crude-oil droplet on the quartz substrate in the presence of the desired aquoues solution. To prepare oil-wet quartz substrates, clean and dry thin sections were aged in the crude oil at 80 °C for 72 h and then the extra crude oil on the surface was cleaned with kerosene. To measure the contact angle, at first a drop of oil was placed on top surface of the thin section, then desired aquoues phase was injected slowly from the bottom to fill the contact angle measurement chamber. The images of the oil droplet were recorded through a digital microscope and the contact angle between the oil and rock surface has been measured through the aquous phase using digimizer software. To record the dynamic changes in wettability, images of the oil drop are taken from the first moment to the next 72 h at the appropriate time intervals until it reaches equilibrium state (no further changes for the last 10 h).

Micromodel tests

In order to inject the fluids into the micromodel, a syringe pump (SP120, Soraco) was used (with the minimum possible injection rate of 0.000003 ml/min). The micromodel setup (Fig. 6) includes a syringe pump, a micromodel holder and micro-model, light source, a microscope, a digital camera and a recording system. Macroscopic and microscopic images were taken by digital camera (SM-A207F/DS) and microscope (Vanpower USB 1000x LED) respectively and they were analyzed by Image-J software.

Dried and cleaned micromodel was vacuumed from gas and then it was fully saturated with the crude oil. The oil-wettability of the grains’ surfaces was created by aging the fully crude-oil saturated micro-model in the oven at 80 °C for two weeks. This time and temperature is selected based on the aging and contact angle tests on the glass surfaces in which one week aging in the same crude oil sample at 80 °C was adequate to change the surface wettability to strongly oil-wet condition. To avoid any pore-plugging due to asphaltene precipitation and also enhancing the process of wettability alteration (by providing fresh polar component towards grains), 1 PV of oil was injected in the micromodel every 8 h.

In all the main experiments the rate of injection fluid was 0.005 ml/min (equal to the velocity of 0.6 m/day). This injection rate is selected based on the criteria of capillary dominant flow regime and is in line with the range of typical velocity of the fluids in the oil reservoirs. Injection of fluids in each flooding period extended until no variations in the saturation of phases was observed and the oil/brine/rock system reached equilibrium, and the recovery curves was plateau. Table 4 lists the performed tests in this research (which are performed at 25 °C). For both micromodels, in the first experiment, brine with the highest amount of salinity (2xcSW) was injected into the micromodel as secondary injection scenario and once the recovery factor reached the plateau, the injection switched to the 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM as tertiary injection scenario. In the 2nd experiment, 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM was injected into an oil saturated micromodel as the secondary injection scenario. In the third experiment, test started with secondary SW injection, which subsequently changed to the tertiary SW + 1000ppm HPAM. In the 4th experiment SW + 1000ppm HPAM solution was injected in secondary mode. In the 5th test, brine solution with the lowest amount of salinity (10xdSW) was injected in secondary mode which followed by tertiary injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM. In the last test, 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM was injected into the micromodel in the secondary mode.

Results and discussion

pH, IFT and contact angles

pH slightly increases with decreasing the salinity and the presence of HPAM (Fig. 7). The amount of divalent cations such as Ca+ 2 and Mg+ 2 in the aqueous phase increases with the increase in the salinity. These cations tend to interact with hydroxide ions (OH⁻) in the solution, which are crucial for maintaining higher pH levels, and as a result the pH decreases with increasing the salinity. As for the polymer, the carboxylic groups in the HPAM structure interact with divalent cations, resulting in reducing the available cations to interact with OH−, and as a result pH shows higher value compared to the counterparts without polymer. Nevertheless differences are insignificant and the measured values for different aqueous samples are in the range of 7.3 to 8.4.

Measured IFT values between the aqueous phases (used in the flooding tests) and crude oil are shown in Fig. 8. Results indicate that for all the samples, the measured equilibrium IFT values are in the range of 15.4 to 5.7 mN.m− 1, with the highest values for the case of 10xdSW (with or without HPAM) and lowest ones for 2xcSW brines (with or without HPAM). With the increase in the amount of cations at higher salinity, the amount of oil polar compounds which can be attracted into interface (via their negatively charged hydrophilic sections) will be promoted, and consequently the oil/brine IFT will be reduced further. In the presence of polymer the amounts of equilibrium IFTs values are slightly higher (compared to the counterpart cases without polymer). As was discussed earlier, the amount of active cations in the solutions reduced with adding polymer, due to ionic bond between oxygen from polymer and cations. As a result, the amount of available cations at the interface (to interact with polar component of oil) will be less and consequently the equibilrium IFTs show higher values in the presence of HPAM.

Measured contact angles in the presence of different brines are shown in Fig. 9. The values are reported based on the angle measured through the aqueous phase (the 180° means strongly oil-wet and 0° means strongly water-wet condition). Results show that the degree of wettability alteration is lowest for 2xcSW solutions and highest for the 10xdSW brines. In addition, presence of HPAM promotes the wettability alteration in the case of each brine sample. The lowest contact angle observed for the 10xdSW + HPAM, in which the ultimate wettability status is neutral-wet (90°).

Divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) form bridges between quartz surface and negative polar compounds of the oil, which makes the surface oil-wet (Fig. 10). Reducing the number of divalent cations at lower salinity leads to break up of these bridges (to compensate the reduced amount of these cations in the aqueous phase). As a result, the attached oil components will be released and the oil-wetness of the surface will be reduced. In the presence of polymer, active oxygen of the HPAM interacts with the bridging cations on the silica surface, which enhances the release of bridging cations from silica surface (Figs. 11 and 12). As a result the wettability of the system becomes less oil-wet compared to the brine samples without the polymer.

Since the main aim of the present study is to investigate the mechanisms of EOR using hybrid low salinity water and polymer, detailed investigation on the adsorption is not included. However, Amiri et al. (2022) proposed that chemical adsorption of HPAM on the sandstone surface plays a significant role in wettability alteration during LSPF. The measured reductions in contact angle and changes in rock/brine zeta potentials confirm this adsorption-driven surface modification mechanism. HPAM adsorption in sandstone is a complex process influenced by factors like polymer type and concentration, salinity, and rock properties39. Adsorption often increases with salinity since salinity can affect polymer chain conformation and interactions with the rock surface. However, the relationship can be non-linear40. Adsorption represents polymer loss from the injected fluid, reducing the effectiveness of the EOR process. From macroscopic point of view, adsorption can lead to pore plugging and permeability reduction, impacting the ability to inject the polymer solution into the reservoir. While adsorption can be detrimental, it also plays a role in altering flow paths and improving sweep efficiency, potentially enhancing oil recovery41.

Rheological tests

Rheological properties of different aqueous phases used in the flooding tests (different brines with HPAM concentration of 1000 ppm) were investigated (Fig. 13). All samples show a yield stress (as the shear stress required to initiate the flow of material) at very low shear rates. At all shear rates, the highest amount of shear stresses belongs to 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM. At shear rates of 1 s− 1 shear stress was 2.13 Pa, while with increasing the shear rate to 1000 s− 1 it reached 18.03 Pa. In the case of SW + 1000 ppm HPAM, shear stresses are lower than 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM (at shear rates of 1 and 1000 s− 1, shear stresses are 0.93 and 8.88 Pa respectively). The changes of shear stresses vs. shear rates are negligible in the case of 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM, as it increased from 0.21 Pa at shear rate of 1 s− 1 to 3.73 Pa at shear rate of 1000 s− 1.

Figure 14 shows measured viscosities vs. shear rates. The highest viscosity at all shear rates belongs to 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM (168 and 18.07 mPa.s at shear rates of 1 and 1000s− 1, respectively). In the case of SW + 1000ppm HPAM, at the lowest shear rate the viscosity is 73.66 mPa.s and at the highest shear rate (1000 s− 1) it decreased to 8.89 mPa.s. HPAM solution with the highest amount of salinity (2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM) showed the lowest viscosity at all shear rates. At shear rate of 1s− 1 the viscosity is 14.76 mPa.s and at the shear rate of 1000s− 1 it declined to 3.1 mPa.s. Results show that with increasing the shear rate, the viscosity of all HPAM solutions decreased and shear thinning behavior is clearly visible. This behavior can be attributed to the molecular alignment, uncoiling and straightening of the polymer chains under shear rates which make the flow easier, and therefore, the viscosity decreases with increasing the shear rate. From another point of view, with decreasing the salinity of brine, repulsive forces between carbocyclic groups of HPAM chains increase, HPAM chains expand, and tend to repel each other and as a result the viscosity increases42. At high salinity, HPAM chains coil around divalent ions (Mg2+ and Ca2+) and electrical double layer around HPAM chains decrease, therefore, HPAM chains shrink and viscosity decreases43.

The experimental results were fit with the Herschel-Bulkley rheological model. The rheological parameters were estimated based on the following equation:

where τ, τy, K, γ and n are shear stress, yield stress, consistency coefficient, shear rate, and flow index, respectively. The fitting parameters of the Herschel–Bulkley equation are presented in Table 5. With increasing the salinity yield stress and consistency coefficient “K” decreased due to losing viscosity. However, the flow behavior index “n” increased with increasing the salinity.

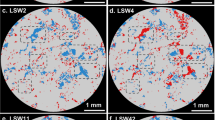

Micromodels tests

In order to understand the effective mechanisms of LSPF in fractured porous media and effect of water composition on the interactions between fracture and matrix, different brines (with and without HPAM) were injected in the designed fractured micromodels. Flooding experiments were repeated to evaluate the accuracy of the results. It should be mentioned that in all experiments, water injection is through the fracture (from left hand side) and production is also through the right-hand side of the fracture (see Fig. 2). In the preliminary tests, different extra low rates i.e., 0.0005 and 0.001 ml/min were tried, however due to the presence of very high permeable fracture in the micro-model, none of the injection fluids (either brines or HPAM solutions), were able to overcome the capillary forces of the oil-wet matrix (Fig. 15). As a result, in the subsequent main tests, the injection rate of the fluids raised to 0.005 ml/min.

Test 1

Secondary 2xcSW injection

Figure 16 shows the distribution of the phases in the fractured micromodel during the secondary injection of 2xcSW. In just 0.01 ml injection, water breakthrough was occurred through the high permeable fracture. Injection continued for 7.2 ml, however no considerable change in the oil saturation of the matrix was observed. The final contact angle for 2xcSW is 175° which shows almost 0º change in the wettability of the system. Surface charges of the micro model grains are negative and cations (e.g., Mg2+ and Ca2+), provide bridges to attach the oil polar compounds (with negative charge) to the surface of the grains which results in oil-wet state of the rock. Because of high amount of divalent ions in the case of 2xcSW, this mechanism is dominant and bridges between oil and surface cannot be broken, and therefore wettability didn’t change. The extended injection of 2xcSW is not able to conquer the capillary forces of the oil wetting layers on the walls of the fracture (Fig. 16e) and water couldn’t imbibe into the matrix medium to sweep the oil (capillary number is equal to 0.07403 × 10− 7 in this case). As a result, very small amount of oil was recovered (14.12% IOIP) which is just due to the production of the fracture oil in place.

Tertiary injection of 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM

In the case of tertiary injection of 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM (Fig. 17), in some limited sections, imbibition of the water into the porous medium was observed and the oil saturation in the matrix was slightly reduced. The recovery factor in this case was raised to 17.33% IOIP. The final contact angle for 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM is 155° which shows 20° wettability alteration (Fig. 9). This shows that addition of HPAM to the high salinity brine is not effective in wettability alteration. Divalent cations in the 2xcSW interact with negative charges of HPAM structure, therefore polymer is not able to effectively react with the bridging cation on the grains of the micromodel and as a result the wettability alteration is minimal. Also, the viscosifying effect of HPAM is not significant considering the high salinity of brine. The limited water encroachment into the matrix, has happened just in most larger pores at the inlet, where the capillary forces are the minimum and might be conquered considering the slightly more favorable wettability condition and higher viscosity of the HPAM solution compared to the 2xcSW case (without HPAM).

Test 2

Secondary injection of 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM

Figure 18 shows the ultimate oil saturation after secondary injection of 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM. Although fracture is saturated with water, the water could not enter the matrix. As a result, recovery factor was insignificant (14.15% IOIP) which is very close to the value obtained for the secondary 2xcSW (which is just due to the production of the fracture oil in place).

Recovery curves during tests 1 and 2 are compared in Fig. 19, which indicates the effect of adding HPAM to 2xcSW in secondary and tertiary modes. Injection of 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM in secondary mode performed almost the same as secondary 2xcSW. This can be explained considering the small effect of HPAM on both wettability alteration and viscosity of the fluid in the case of 2xcSW, which in turn has minimal effect on mobility ratio and capillary number. Contrary to the secondary injection, tertiary injection of HPAM solution showed higher oil recovery compared to both secondary 2xcSW and secondary 2xcSW + HPAM.

Microscopic images during the tertiary 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM (Fig. 20) show that oil wetting layers are stable on the fracture/matrix boundaries and the grains of the matrix remain oil-wet. Due to effect of the applied drag force by the HPAM solution, oil layers (remained after secondary 2xcSW) discharge towards the downstream and form some temporary oil blobs on the walls of the fracture (peeling off mechanism, Fig. 20b). Formation of these blob-like oil phase, restricts the flow of aqueous phase in the fracture and promotes the diversion of the water towards the matrix at the upstream of these blobs. As a result, brine can enter into small fraction of the larger pores in the vicinity of the fracture, where the capillary forces are smallest (the encroachment is promoted due to the high viscosity and low mobility of the brine + HPAM solution, Fig. 21). This mechanism which is not observed during the secondary 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM and secondary 2xcSW injections is responsible for additional oil recovery in the case of tertiary 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM. However, these oil blobs are limited and temporary and as shown in Fig. 20c, after 24 h of injection the thickness of oil film on the walls of the fracture decreased remarkably as these oil wetting layers discharges to the downstream of the micromodel. Since the viscous forces (capillary number of 0.797 × 10− 7 ) are not adequate to break the oil wetting layers in the model dominantly, water cannot enter most of the oil-wet pores (Fig. 21). As a result, almost all of the pores of the matrix medium remain un-swept. Figure 21 also shows that although aqueous phase has entered the matrix in one or two locations and displaced considerable oil from the pores, the grains are remained oil-wet.

Test 3

Secondary injection of SW

This test started by injecting SW into the completely oil saturated micromodel, which extended for 24 h and distribution of phases were monitored (Fig. 22). In just 0.01 ml injection, water breakthrough was occurred through the high permeable fracture. Injection continued for 24 h (7.2 ml injection), however no considerable change in the oil saturation of the matrix was observed. The small amount of recovered oil (14.4%IOIP) is just due to the production of the fracture oil in place.

Wettability alteration for SW is just 25º (ultimate contact angle of 150°) which is very small. This ineffective wettability alteration is also confirmed in the flooding tests since the oil wetting layers are stable on the fracture boundary and the grains of the matrix remain oil-wet (Fig. 23). However as shown in Fig. 23, after 24 h of injection the thickness of oil film on the walls of the fracture decreased remarkably due to effects of viscous forces and the applied drag force which discharge the oil phase towards the downstream of these layers. Contrary to the cases with HPAM (as already discussed earlier), in this case (as well as other brines without HPAM) during the discharge of wetting oil layers, formation of oil blobs on the fracture’s walls (see Fig. 20) was not observed, which can be attributed to the low viscosity of the displacing fluid. Nevertheless, the present viscous forces are not adequate to break the oil wetting layers (capillary number of 0.0391 × 10− 7) and water cannot enter strongly oil-wet pores (Fig. 24) and as a result most of the pores of the matrix remain un-swept (Fig. 22b).

Tertiary injection of SW + 1000ppm HPAM

Subsequently, 1000ppm HPAM + SW was injected into the fractured porous media in tertiary mode. The HPAM solution effectively invaded the matrix and recovery factor reached to 42.88%IOIP (Fig. 25). As it is observed in the microscopic image (Fig. 25) the oil wetting layers on some grains was swept completely (red ovals) by brine invasion. These are the grains which are located adjacent to the fracture and in the main flow path of the polymer solution (larger pores). It should be noticed that based on the limited degree of wettability alteration (ultimate contact angle of 130°), this observation is mainly attributed to the high viscosity of the aqueous phase in this case and the resultant applied drag forces on the oil wetting layers. These high drag forces, peel off the oil wetting layers from the grains which are located in the main flow path of polymer solution. Nevertheless, in the adjacent smaller pores the oil wetting layers remained stable on the grains’ surfaces (red arrows) or the pores even remained completely unswept (blue ovals).

The final contact angle for SW + 1000ppm HPAM is 130º, which is 20° less than SW case (without HPAM). Although the difference in wettability alteration is small, its synergy with the high viscosity of the HPAM solution, is clearly adequate to trigger the entrance of the displacing fluid into the matrix (Fig. 25c).

Test 4

Secondary injection of SW + 1000ppm HPAM

Figure 26 shows the distribution of phases in micromodel during the secondary injection of SW + 1000ppm HPAM. Although the secondary injection of SW + 1000ppm HPAM has a considerable effect on enhanced oil recovery, but it couldn’t sweep the oil as much its tertiary counterpart, and in many areas of the matrix oil remained unswept. In fact, the oil recovery in this process is 35.4% which is 7.48% less than its tertiary counterpart. Microscopic images (Fig. 26d) show that in some parts of the matrix, the oil layer on the grains which are located in the main flow stream of the aqueous phase are very narrow. In some larger pores, the oil wetting layers are peeled off the grains by the polymer solution and just some very small droplets are remained on the surface (red arrows in Fig. 26c). Considering the high ultimate contact angle in the case of this (130°) this observation is attributed to the drag forces (peeling off mechanism) due to high viscosity of the polymer solution (72 cp.).

Recovery curves of test 3 and 4 are compared in Fig. 27. Injection of SW + 1000ppm HPAM in both secondary and tertiary modes showed higher oil recovery compared to the SW without HPAM, which proves the positive effect of adding HPAM to SW. This superior performance is attributed to the considerably higher viscosity of the HPAM solution (72 cp.) compared to its counterpart brine without polymer (1.12 cp.). The higher performance of tertiary SW + 1000ppm HPAM compared to its secondary counterpart can be explained by the formation of oil bridges in both fracture and matrix (Fig. 28) as the high viscosity polymer solutions peels off the residual oil wetting layers (formed during the secondary SW injection).

Test 5

Secondary injection of 10xdSW

Figure 29 shows macro-scale image of the fractured porous media at the end of secondary 10xdSW. The injection fluid entered the fracture and after 0.01 ml injection, brine breaks through at the outlet of the micro-model. The test was continued for 4 PV but no changes was observed in the oil saturation of the matrix and the recovery factor was just 14.88% IOIP (which is due to the production of the oil inside the fracture).

Among the investigated brines (without HPAM), 10xdSW with 50º had the highest degree of wettability alteration (ultimate contact angle of 125°). The final contact angle is considerably less than the case of 2xcSW + HPAM (with ultimate contact angle of 155°, Fig. 9), and is very close to the SW + HPAM (with ultimate contact angle of 130°). However contrary to these cases, 10xdSW (without HPAM) was not able to enter the matrix. This observation supports the idea of the effect of low mobility and high viscous forces in the efficiency of HPAM solutions. In the case of 10xdSW with viscosity of 1 cp., the mobility of the injectant fluid in the fracture is high and low viscous forces (capillary number is equal to 2.30 × 10− 9) are not able to overcome the high capillary force of the matrix oil-wet pores.

Tertiary injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM

In tertiary injection of 1000ppm HPAM + 10xdSW, a large amount of oil of the matrix was swept (Fig. 30) and recovery factor reached 74.89% IOIP (increased by 60.01% compared to the preceding secondary injection of 10xdSW).

Wettability alteration in the case of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM is 85º (final contact angle of 90° which is known as neutral-wet condition). Taking into account the low concentration of cations in low salinity brine, HPAM chains are not reacted in the brine and there is a higher chance (compared to the high salinity brines) for them to interact with the adsorbed cations on the rock surface (which are acting as bridge between rock negative surface and oil polar component). Therefore the bonds between oil droplets and rock surface break, and the wettability of surface changes dramatically towards less oil-wet (Figs. 10 and 11). Distribution of the phases after secondary injection of 10xdSW and tertiary injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM are compared in Fig. 31. In the case of 10xdSW, oil wetting layers are thick and quite stable, while for the case of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM, the oil layers are narrow and are even ruptured by the peeling off mechanism of the polymer solution in some sections, where injectant fluid can enter the pores of the matrix (red ovals).

It is obvious in Fig. 32 that the oil is completely swept from the walls of some grains (red arrows) which proves the synergistic effect of high viscosity of HPAM solution and large wettability alteration on oil displacement which leads to increasing oil recovery. It should be mentioned that unlike HPAM solutions in 2xcSW and SW (Figs. 20 and 28, respectively), in the case of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM, breaking the brine continuous phase by oil filament was not observed. This is attributed to the thin oil wetting layers on the fracture walls (due to large wettability alteration) after the preceding secondary 10xdSW injection (compared to the thick residual oil layers after secondary 2xcSW and SW injections).

Test 6

Secondary injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM

In this test the 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM solution was injected to the oil saturated micromodel (Fig. 33). The encroachment of polymer solution into the matrix and sweeping the oil resulted in an oil recovery factor of 58.21% IOIP. This considerable oil recovery is attributed to the synergistic effect of wettability alteration and high viscosity of the 10xdSW + HPAM. Effect of viscous forces on peeling off the wetting oil layers from the surface of grains are obvious after tertiary injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM (red circles in Fig. 34).

Recovery curves of test 5 and 6 are compared in Fig. 35. Injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM in both secondary and tertiary modes showed considerably higher oil recovery compared to the secondary injection of 10xdSW without HPAM, which proves the positive effect of adding HPAM. 10xdSW + HPAM has a considerably higher viscosity compared to the 10xdSW without polymer. This viscosity reduces the mobility of the aqueous phase inside the fracture, which in turn enhances the transverse flow of the polymer solution towards the matrix. From another point of view, due to the high viscosity of the polymer solution viscous forces can overcome the capillary forces of the pores near the fracture, which dramatically enhances the brine encroachment into the matrix compared to the counterpart case without HPAM.

Ultimate oil recovery in the case of tertiary injection of 10xdSW + HPAM solution is 16.68% higher compared to secondary 10xdSW + HPAM. The encroachment of the brine inside the matrix (macroscopic sweep efficiency) are enhanced in the case of tertiary injection (Fig. 30e) compared to its secondary counterpart (Fig. 33f). During the 10xdSW secondary injection scenario, the wettability of some pores adjacent to the matrix is changed from strongly oil-wet to neutral-wet. In spite of this wettability alteration, 10xdSW cannot effectively enter the matrix due to its high mobility through the fracture (low viscosity of the brine) and negligible viscous forces (compared to the strong capillary forces of the small pores). In the case of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM tertiary injection, the polymer solution was injected in the system in which the wettability of the fracture and some of the pores adjacent to the fracture is already changed from strongly oil-wet to intermediate-wet (during the former secondary 10xdSW injection). High viscosity of the polymer solution, results in its low mobility through the fracture as well as dominance of the viscous forces on capillary forces. Both these phenomena promote the entrance of aqueous phase into the matrix, which explain the superior performance of tertiary 10xdSW + HPAM compared to the preceding secondary 10xdSW. The same mechanisms contribute to the enhanced performance of secondary 10xdSW + HPAM compared to the secondary 10xdSW.

The amount of ultimate oil recovery at the end of tertiary 10xdSW + HPAM is higher compared to secondary 10xdSW + HPAM. This can be also attributed to the fact that in the case of tertiary 10xdSW + HPAM the diversion of the flow into the matrix is promoted since the wettability of some of the pores are already changed toward neutral-wet by former 10xdSW, while in the case of secondary 10xdSW + HPAM, the initial wettability of the system is strongly oil-wet. This means that in secondary injection, part of HPAM in polymer solution is interacted with the bridging cations in the fracture and adjacent pores to change the wettability towards neutral-wet. It should be mentioned that in the secondary injection, the flow diversion towards matrix is dominant before the breakthrough and there is no considerable change in distribution of the phases in the matrix afterwards.

Effect of Brine salinity

The results of secondary injection of different brines (10xdSW, SW and 2xcSW) without and with HPAM are shown in Figs. 36 and 37. Recovery factors of all of the mentioned brines (without HPAM) in secondary injection scenario were very close to each other (14.88, 14.4 and 14.12% IOIP for 10xdSW, SW and 2xcSW respectively). In the presence of HPAM, the obtained recovery factors of secondary injections are considerably different. In the case of 10xdSW + HPAM recovery factor was 58.21% IOIP which was considerably higher than the other two HPAM solutions (35.4 and 14.15% IOIP for SW + HPAM and 2xcSW + HPAM respectively).

In Fig. 38 recovery factors of brines without HPAM in secondary injection scenario and brine after adding HPAM in tertiary injection scenario are clearly visible. As previously mentioned, the amount of recovered oil by all of the brines in secondary injection mode were close to each other but in tertiary injection scenario significant differences were observed. Generally, the highest amount of oil recovery belonged to tertiary injection of 10xdSW + 1000ppm HPAM which was 74.89% IOIP. Recovery factor in tertiary injection mode for SW + 1000ppm HPAM was 42.88% IOIP and for 2xcSW + 1000ppm HPAM was 17.33% IOIP.

It should be mentioned that formation of microemulsion was not dominant observation in the micromodel flooding tests; therefore, it cannot be the key recovery mechanism. Furthermore, in this study, micromodels were not coated with any chemical or mineral before running the tests. As a result, fine migration could not be considered as an effective mechanism. Also the measured pH values for different aqueous phases are in the range of 7.3 to 8.5, so the effect of pH increment is minimal. In addition, since the IFT (as a fluid/fluid interaction) values are higher in the case of 10xdSW brines (in the presence and absence of HPAM) and lowest in the case of 2xcSW brines, IFT variations cannot be the contributing mechanism behind the observed additional oil recovery. High viscosity of the HPAM solutions results in low mobility of the injectant in the fracture and high viscous forces. As was discussed earlier, based on macroscopic and microscopic images, both these phenomena promote the intrusion of the HPAM solution into the matrix and higher oil recovery factor.

The ratio of the viscous force to the capillary force is represented by capillary number (NCa) and is defined as:

where v is the velocity of displacing fluid, µ is the viscosity of water, σ is the interfacial tension between water and oil, and NCa is a dimensionless variable. Based on this formula, increasing capillary number by either increasing viscosity of displacing fluid or decreasing interfacial tension decreases residual oil trapped by capillary forces. The amount of viscosity, equilibrium IFT and capillary number for each brine sample (with and without polymer) were calculated and presented in Table 6 (the velocity in this study is 3.47 × 10− 8 m/s). Table 7 shows the amount of residual oil saturation at the end of each injection scenario.

Capillary desaturation curve (CDC, Fig. 39) shows that for the case of all secondary injection scenarios in the absence of HPAM, the amount of residual oil saturations are very close and insensitive to the variation of the capillary number (Nca. is in the range of 10− 9 to 10− 8 for these cases). In addition, in the case of both secondary and tertiary injection of 2xcSW + HPAM, the amount of residual oil saturation change is insignificant although the Nca. is increased to 8 × 10− 8. With further increase in Nca. the residual oil saturation reduction is obvious. It can be concluded that 8 × 10− 8 is around the critical capillary number for the present system, where for higher capillary numbers viscous forces are dominating the capillary forces and reduce the amount of residual oil saturation accordingly.

Although the capillary numbers in the case of secondary and tertiary injections of the HPAM solutions are the same, the amount of residual oil saturation is lower for the tertiary counterparts. As discussed in the previous sections, this is attributed to the peeling off mechanism of HPAM solutions on the oil wetting layers (on the walls of the fracture), which bring about formation of oil blobs (2xcSW + HPAM) or even oil bridges (SW + HPAM) in the fracture. This in turn results in further reduction in the mobility of the HPAM solution in the fracture which promotes the diversion of flow in transverse direction towards the pore in the matrix. As is obvious from Fig. 39, the amount of difference between residual oil saturations increases with the dilution of the brine from 2xcSW to 10xdSW. As explained in the previous sections, this is due to the beneficial effect of wettability alteration of the walls of the fracture during the preceding secondary brine injection, which is especially very effective in the case of 10xdSW, as the wettability is changed from strongly oil-wet to neutral-wet state.

Future studies

-

Changes in oil composition, particularly the presence of surface-active components like asphaltenes, resins, and waxes, can affect the IFT37,44,45. Asphaltenes, Resins and Waxes components in crude oil, can act as surfactants and reduce the IFT between oil and brine. The acid and base numbers of crude oil, which reflect the concentration of acidic and basic components, can also influence IFT. For example, at basic conditions, acidic species can interact with other compounds to reduce IFT. The presence and concentration of polar components in crude oil can affect its interaction with brine, particularly with the hydration shell of ions, and thus influence IFT.

-

In brine/oil system, both temperature and pressure can influence wettability and IFT. However the final effect depends on other involved parameters. For example, Okasha (2018) experiments showed that the IFT between dead oil and brine decreased with increasing temperature and increased with increasing pressure at constant temperature46. However, for live oil-brine system, they observed an opposite trend, in which the IFT values increased with temperature. At reservoir conditions, the IFT of live oil was higher than that of dead oil. The measured contact angle values for live oil-brine/rock system increased with temperature. Tang and Morrow (1997, 2005) reported a transition toward more water-wet behavior in Berea sandstone, when temperature increased from ambient to 75 °C under water imbibition/flooding process4,47. Lu et al. (2017) experiments on an oil sample, produced from a sandstone reservoir, tested on mica and quartz substrates showed that raising the temperature from 25 to 50 °C has no discernible effect on measured contact angle, regardless of substrate type, brine type, or salt concentration48. However, testing another oil sample, obtained from a carbonate reservoir, on calcite substrates, showed that contact angles decrease as the temperature increases from 25 to 65 °C, and this temperature effect also strongly depends upon the brine type and salt concentration. In the case of presence of polymer, wettability alteration can be influenced by other factors as well, e.g., polymer adsorption and temperature-induced desorption of carboxylic acids49,50. It is believed that increased temperature can lead to a shift in wettability towards a more water-wet state. Polymers can adsorb onto the rock surface, influencing wettability. Although at higher temperatures, the adsorption of some polymers may decrease, the overall effect can still be a shift towards water-wet conditions due to other factors like desorption of carboxylic acids. Carboxylic acids, which contribute to oil-wetting of the rock, may be desorbed from the rock surface at higher temperatures, promoting a more water-wet state. Generally, it can be stated that in brine/oil/rock systems, temperature increase tends to enhance the wettability alteration of the rocks towards more water-wet, while pressure has a less direct significant impact (though it might affect wettability through influencing fluids properties and interfacial tension especially in the case of live oils).

-

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for the practical implementation of hybrid low salinity–polymer flooding in oil-wet double porosity single permeability fractured systems. The demonstrated effectiveness of low salinity brines combined with optimized polymer concentrations in enhancing wettability alteration and promoting matrix-fracture interaction suggests a promising strategy for EOR field applications, especially where conventional waterflooding fails. Future researches might focus on performing high pressure high temperature experiments, scaling micromodel observations to core-scale or pilot field tests, as well as investigating long-term chemical retention, adsorption, and economic feasibility studies.

Conclusions

In this research, the effects of brine salinity and presence of polymer on oil displacement mechanisms of effectiveness in double porosity single permeability fractured porous media are studied. Three different brine salinities along with absence and presence of HPAM (1000 ppm) were considered. Experiments include both secondary and tertiary injection modes.

-

In secondary injection scenario and absence of polymer, the oil recovery increased with decreasing the salinity of injected brine. Nevertheless, the difference between different cases as well as the amount of enhanced oil recovery from matrix were negligible.

-

Addition of the HPAM to the injectant in the tertiary injection scenario, enhanced the oil recovery from the matrix. 2xcSW + HPAM was not able to increase the oil recovery significantly, however for SW and 10xdSW, adding HPAM increased the oil recovery by 28.48% and 60.01% respectively which proves the positive effect of hybrid LSPF.

-

In secondary injection modes of 10xdSW and SW, addition of HPAM improved the oil recovery compared to the counterpart injectants without polymer. However, the effect of hybrid injection with HPAM was negligible in the case of 2xcSW.

-

For all the investigated hybrid cases, ultimate oil recovery factors were higher in the case of tertiary injections compared to the secondary counterparts.

-

High viscosity of the HPAM solutions (especially in the cases of SW and 10xdSW brines), results in low mobility of the injectant in the fracture and high viscous forces (compared to the capillary forces of oil-wet matrix). Both these phenomena promote the intrusion of the HPAM solution into the matrix and higher oil recovery factors compared to the counterpart brines without HPAM.

-

In the cases of 2xcSW + HPAM and SW + HPAM tertiary injection, peeling off mechanism of the oil wetting layers on the fracture walls, is an axillary mechanism which promotes the formation of oil blobs and bridges in fracture. This mechanism also reduces the mobility of the polymer solution in the fracture and enhances the diversion of the flow towards the matrix. The effectiveness of the mechanism is owed to the already low mobility of the solution as well as high capillary forces in the presence of HPAM.

-

High degree of wettability alterations of the fracture walls and some of the pores (towards neutral-wet condition) was observed in the secondary 10xdSW. This phenomenon acts as the axillary recovery mechanism, in the case of following tertiary 10xdSW + HPAM, as it promotes the imbibition of the polymer solution into the matrix. Peeling off mechanism in the fracture was minimal in this case, due to the thin oil layers at the end of secondary 10xdSW.

Data availability

The datasets are available upon the request from corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- 10xdSW:

-

10 time diluted sea water

- 2xcSW:

-

2 time concentrated sea water

- CA:

-

Contact Angle

- EOR:

-

Enhanced Oil Recovery

- HPAM:

-

Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide

- IOIP:

-

Initial Oil in Place

- IFT:

-

Interfacial Tension

- LSPF:

-

Low Salinity Polymer Flooding

- LSW:

-

Low Salinity Water

- LSWF:

-

Low Salinity Water Flooding

- PDI:

-

Potential Determining Ions

- PV:

-

Pore Volume

- SW:

-

Sea Water

- TDS:

-

Total Dissolved Solids

- ZP:

-

Zeta Potential

References

Carll, J. F. The geology of the oil regions of Warren, Venango, Clarion and Butler Counties, Report III, Board of Commissioners for the Second Geological Survey, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. (1880).

Wei, J., Zhang, D., Zhang, X., Zhao, X. & Zhou, R. Experimental study on water flooding mechanism in low permeability oil reservoirs based on nuclear magnetic resonance technology, energy. Part. B. 278, 127960 (2023).

Jadhunandan, P. P. & Morrow, N. R. Effect of wettability on waterflood recovery for crude-oil/brine/rock system. SPE Form. Eval. 10 (1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.2118/22597-PA (1995).

Tang, G. Q. & Morrow, N. R. Salinity, temperature, oil composition, and oil recovery by waterflooding. SPE Reserv. Eng. 12 (4), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.2118/36680-PA (1997).

Tang, G. Q. & Morrow, N. R. Influence of Brine composition and fines migration on crude oil/brine/rock interactions and oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 24 (2–4), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-4105(99)00034-0 (1999).

Alotaibi, M. B., Azmy, R. M. & Nasr-El-Din, H. A. Wettability studies using low-salinity water in sandstone reservoirs. Proceedings of the Annual Offshore Technology Conference, 3, 1808–1822. (2011). https://doi.org/10.4043/20718-ms

Zahid, A., Shapiro, A. A. & Skauge, A. Experimental studies of low salinity water flooding carbonate: A new promising approach, paper SPE 155625 presented at the SPE EOR Conference at Oil and Gas West Asia, held by the Society of Petroleum Engineers, Muscat, Oman, 16–18 April, (2012). https://doi.org/10.2118/155625-MS

Siadatifar, S. E., Fatemi, M. & Masihi, M. Pore scale visualization of fluid-fluid and rock-fluid interactions during low-salinity waterflooding in carbonate and sandstone representing micromodels. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 198, 108156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.108156 (2021).

Garcia-Olvera, G. & Alvarado, V. The Potential of Sulfate as Optimizer of Crude Oil-Water Interfacial Rheology to Increase Oil Recovery During Smart Water Injection in Carbonates. SPE - DOE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, (2016). https://doi.org/10.2118/179544-MS

Tahir, M., Hincapie, R. E. & Ganzer, L. Influence of Sulfate Ions on the Combined Application of Modified Water and Polymer Flooding—Rheology and Oil Recovery. Energies 2020, Vol. 13, Page 2356, 13(9), 2356. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/EN13092356

Hatzignatiou, D. G., Giske, N. H. & Stavland, A. Polymers and polymer-based gelants for improved oil recovery and water control in naturally fractured chalk formations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 187, 302–317 (2018).

Mahmoudzadeh, A., Fatemi, M. & Masihi, M. Microfluidics experimental investigation of the mechanisms of enhanced oil recovery by low salinity water flooding in fractured porous media. Fuel 314 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.123067 (2022).

Torrijos, P. et al. An experimental study of the low salinity smart Water - Polymer hybrid EOR effect in sandstone material. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 164, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.01.031 (2018).

Javadi, A. H. & Fatemi, M. Impact of salinity on fluid/fluid and rock/fluid interactions in enhanced oil recovery by hybrid low salinity water and surfactant flooding from fractured porous media. Fuel 329, 125426 (2022).

Ghaedi, A., Nabipour, M. & Azdarpour, A. Mechanistic investigation of using low salinity alkaline surfactant solutions in carbonate reservoirs based on Polarity of crude oil. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 123098 (2023).

Ahmadi, Y., Hemmati, M., Vaferi, B. & Gandomkar, A. : Applications of nanoparticles during chemical enhanced oil recovery: A review of mechanisms and technical challenges. J. Mol. Liq., 126287. (2024).

Lopes, L. F., Silveira, B. M. & Moreno -State, Z. L. R. B. Rheological Evaluation of HPAM fluids for EOR Applications. In International Journal of Engineering & Technology IJET-IJENS (Vol. 14, Issue 03). (2014).

Sheng, J. J., Leonhardt, B. & Azri, N. Status of polymer-flooding technology. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 54 (2), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.2118/174541-PA (2015).

Shiran, B. & Skauge, A. Enhanced oil recovery (EOR) by combined low salinity water/polymer flooding. Energy Fuels. 27 (3), 1223–1235. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef301538e (2013).

Vermolen, E. C. et al. Pushing the Envelope for Polymer Flooding Towards High-temperature and High-salinity Reservoirs with Polyacrylamide Based Ter-polymers. presented at the SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and (2011). https://doi.org/10.2118/141497-MS

Elhajjaji, R. R. et al. Systematic study of viscoelastic properties during polymer-surfactant flooding in porous media. Soc. Petroleum Eng. - SPE Russian Petroleum Technol. Conf. Exhib. 2016. https://doi.org/10.2118/181916-/MS (2016).

Shakeel, M., Pourafshary, P. & Hashmet, M. R. Hybrid Engineered Water–Polymer Flooding in Carbonates: A Review of Mechanisms and Case Studies. Applied Sciences 2020, Vol. 10, Page 6087, 10(17), 6087. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/APP10176087

Kakati, A., Bera, A. & Al-Yaseri, A. A review on advanced nanoparticle-induced polymer flooding for enhanced oil recovery. Chem. Eng. Sci. 262, 117994 (2022).

Vermolen, E. C. M., Almada, P., Monica, Wassing, B. M., Ligthelm, D. J. & Masalmeh, S. K. : Low-Salinity Polymer Flooding: Improving Polymer Flooding Technical Feasibility and Economics by Using Low-Salinity Make-up Brine. Paper presented at the International Petroleum Technology Conference, (2014). https://doi.org/10.2523/IPTC-17342-MS

Kozaki, C. Efficiency of Low Salinity Polymer Flooding in Sandstone Cores. Master Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA. (2012).

Almansour, A. O. et al. Efficiency of enhanced oil recovery using polymer-augmented low salinity flooding. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 7, 1149–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-017-0331-5 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. Performance of Low Salinity Polymer Flood in Enhancing Heavy Oil Recovery on the Alaska North Slope. (2020). https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2020-1082

Sedaghat, H., Ghazanfari, M. H., Parvazdavani, M. & Morshedi, S. Experimental investigation of microscopic/macroscopic efficiency of polymer flooding in fractured heavy oil Five-Spot systems. J. Energy Res. Technol. 135 (3). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4023171 (2013).

Algharaib, M., Alajmi, A., Gharbi, R. & & Improving polymer flood performance in high salinity reservoirs. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 115 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2014.02.003 (2014).

Emamimeybodi, H., Kharrat, R. & Ghazanfari, M. H. Effect of Heterogeneity of Layered Reservoirs on Polymer Flooding: An Experimental Approach Using 5- Spot Glass Micromodel. In Europec/EAGE Conference and Exhibition (p. SPE-113820-MS). (2008). https://doi.org/10.2118/113820-MS

Yousefvand, H. & Jafari, A. Enhanced oil recovery using polymer/nanosilica. Procedia Mater. Sci. 11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mspro.2015.11.068 (2015).

Cancela, B. R., Palermo, L. C. M., de Oliveira, P. F. & Mansur, C. R. Rheological study of polymeric fluids based on HPAM and fillers for application in EOR. Fuel 330, 125647 (2022).

Baek, K. H., Argüelles-Vivas, F. J., Abeykoon, G. A., Okuno, R. & Weerasooriya, U. P. Low-tension polymer flooding using a short-hydrophobe surfactant for heavy oil recovery. Energy Fuels. 34 (12). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02720 (2020).

Jung, J. C., Zhang, K., Chon, B. H. & Choi, H. J. Rheology and polymer flooding characteristics of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide for enhanced heavy oil recovery. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 127, 4833–4839. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.38070 (2013).

Unsal, E., Ten Berge, A. B. G. M. & Wever, D. A. Z. Low salinity polymer flooding: lower polymer retention and improved injectivity. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 163, 671–682 (2018).

Abdullahi, M. B., Jufar, S. R., Kumar, S., Al-shami, T. M. & Negash, B. M. Synergistic effect of Polymer-Augmented low salinity flooding for oil recovery efficiency in Illite-Sand porous media. J. Mol. Liq. 358, 119217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119217 (2022).

Farhadi, H., Ayatollahi, S. & Fatemi, M. The effect of Brine salinity and oil components on dynamic IFT behavior of oil-brine during low salinity water flooding: diffusion coefficient. EDL establishment time, and IFT reduction rate. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 196, 107862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. petrol.2020.107862 (2021).

Amiri, M., Fatemi, M. & Delijani, E. B. Effect of Brine salinity and hydrolyzed polyacrylamide concentration on the oil/brine and brine/rock interactions: implications on enhanced oil recovery by hybrid low salinity polymer flooding in sandstones. Fuel 324, 124630 (2022).

Ali, M. & Mahmud, H. B. : The effects of concentration and salinity on polymer adsorption isotherm at sandstone rock surface. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 78, No. 1, p. 012038). IOP Publishing. (2015).

Motaz, S. & Jadhawar, P. Surface complexation modeling of HPAM polymer–Brine–Sandstone interfaces for application in Low-Salinity polymer flooding. Energy Fuels. 37, 9, 6585–6600 (2023).

Alajmi, A., Algharaib, M. & Ali, M. Experimental study on the injectivity, adsorption, and in-situ rheology of HPAM polymer in intact and fractured sandstone. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 15, 58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-025-01962-4 (2025).

Al-Hamairi, A. & AlAmeri, W. Development of a novel model to predict HPAM viscosity with the effects of concentration, salinity and divalent content. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 10, 1949–1963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-020-00841-4 (2020).

Mao, J. et al. Design of salt-responsive low-viscosity and high-elasticity hydrophobic association polymers and study of association structure changes under high-salt conditions. Colloids Surf., A. 650 (June), 129512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129512 (2022).

Soleymanzadeh, A. et al. Theoretical and experimental investigation of effect of salinity and asphaltene on IFT of Brine and live oil samples. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol. 11, 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-020-01020-1 (2021).

Mazinani, S., Farhadi, H. & Fatemi, M. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the impact of crude-oil on the wettability behavior of calcite and silicate due to low salinity effect. Fuel 349, 128608 (2023).

Okasha, T. M. : Investigation of the effect of temperature and pressure on interfacial tension and wettability, SCA2018_062, presented at the International Symposium of the Society of Core Analysts, Trondheim, Norway. (2018).

Tang, G. Q. & Morrow, N. R. : Wettability Control by Adsorption from Crude Oil-Aspects of Temperature and Increases Water Saturation. In Paper Presented in Int’l Symposium of Society of Core Analysts, Toronto, Canada. (2005).

Lu, Y., Najafabadi, N. F. & Firoozabadi, A. Effect of temperature on wettability of oil/brine/rock systems. Energy Fuels. 31 (5), 4989–4995 (2017).

Li, Z. et al. Microscale effects of polymer on wettability alteration in carbonates. SPE J. 25, 1884–1894. https://doi.org/10.2118/200251-PA (2020).

Hamouda, A. A. & Karoussi, O. Effect of temperature, wettability and relative permeability on oil recovery from oil-wet chalk. Energies 1 (1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.3390/en1010019 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Sharif University of Technology for supporting this research as a part of QB030713 research program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.: Implementation, Investigation, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Writing Original DraftM.F.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing Original Draft, Review and Editing, Resources, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amiri, M., Fatemi, M. Microfluidics study on immiscible displacement mechanisms of oil by hybrid low salinity water and polymer in fractured porous media. Sci Rep 15, 29630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15609-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15609-1