Abstract

This study aimed to ascertain the incidence, clinical characteristics, and risk factors of hospital-acquired pressure injuries in neurosurgery inpatients and to provide a reference for preventive care. Adhering to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines, we conducted a prospective cohort study involving 1,192 patients admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery at a grade A tertiary hospital in western China from April 2023 to March 2024. During a total of 14,091 patient-days of follow-up, the incidence density of hospital-acquired pressure injuries was 0.003 per patient-day, with a cumulative incidence of 3.6%. Standardized forms were utilized to collect demographic, clinical, laboratory, and pressure injury data. The study revealed that the buttocks (20 cases, 37%) and sacral region (13 cases, 24.1%) were the predominant sites of hospital-acquired pressure injuries, predominantly presenting as stage 1 (21 cases, 38.9%) and stage 2 (27 cases, 50%) pressure injuries. Edema (P = 0.014) and albumin (P = 0.049) were identified as independent risk factors for the development of hospital-acquired pressure injuries. The results of this study highlight the need to monitor patients’ edema status and albumin levels, emphasize the importance of rapid control of acute inflammation, and suggest appropriate albumin supplementation to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired pressure injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pressure injury (PI) is a localized injury to the skin and subcutaneous tissue resulting from pressure or the combined effects of pressure and shear forces, typically manifesting at bony prominences or areas in contact with medical devices1. PI occurring beyond 24 h post-hospital admission is classified as a hospital-acquired pressure injury (HAPI)2. PI is a sensitive hospital indicator closely linked to the quality of clinical nursing care3. Based on research surveys, the overall prevalence of PI among hospitalized adults was 12.8%, with an overall incidence rate of HAPI at 8.4%4. Catherine VanGilder reported in a decade-long research study that the prevalence of HAPI among hospitalized patients in the United States ranges from 3.1–6.2%5. Another study reported the overall incidence rates of PI and HAPI in intensive care units in China as 12.36% and 4.31%, respectively6. As a global public health concern, HAPI not only elevates treatment costs for patients but also impose a significant economic burden on the healthcare system7,8,9. According to a survey, the average cost of HAPI treatment for patients in the United States during hospitalization is $18,00010, with the annual U.S. fiscal expenditure on HAPI treatment reaching as high as $26.8 billion11. A recent cost-of-illness analysis estimated that PIs in Australian public hospitals incurred a total cost of $9.11 billion, with HAPIs accounting for approximately $5.5 billion of this expenditure8.

Most HAPIs are preventable. Accurate and effective risk assessment is crucial for preventing HAPIs, as it can substantially reduce patient readmission and mortality rates, and lower medical expenses12. The Braden Scale is currently a widely used assessment tool for PI in general wards. It evaluates PI risk across six dimensions: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, friction, and shear. A lower total score indicates a higher risk of developing a PI13. However, a meta-analysis concluded that the Braden Scale exhibits only moderate predictive validity for assessing PI risk, attributed to variations across studies14. Referring to the “Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline,” it is recognized that factors such as lack of physical activity, advanced age, diabetes, inadequate perfusion and oxygenation, malnutrition, and other indicators contribute to the development of HAPI1,15. Moreover, the Braden Scale has shown limited applicability in specialized units such as emergency departments and intensive care units (ICU)14. Among neurosurgical patients, those with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury admitted to the ICU have a reported pressure injury incidence ranging from 6.5 to 20%, largely attributable to disease-related hemodynamic instability, immobility, and prolonged pressure over prominent bony areas16. This heightened risk underscores the need for tailored assessment approaches in this population. Therefore, the present study aims to clarify the overall incidence of HAPI among neurosurgical inpatients and to explore the complex interplay of contributing risk factors, with the goal of informing clinical judgment and improving targeted prevention strategies.

Materials and methods

Research design and object

This study is a prospective cohort study adhering to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. It was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.chictr.org.cn) under registration number ChiCTR2300070879. We gathered data from 1,192 patients admitted to the neurosurgery department of a grade A tertiary hospital in western China from April 30, 2023, to March 28, 2024. Inclusion criteria comprised patients older than 18 years who were admitted to the neurosurgical service for at least 24 h due to cerebrovascular disease, intracranial tumors, traumatic brain injury, or congenital malformations and who had no evidence of PI at admission. Exclusion criteria encompassed patients with conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, burns, other skin injuries, or instances of polytrauma, and our study did not include medical device-related pressure injuries (MDRPIs). Follow-up endpoints included (i) occurrence of PI and (ii) discharge from neurosurgery or mortality.

Data collection and classification

A data collection tool is designed and developed for this study, encompassing demographic data, general clinical information, and laboratory test results. Demographic details (sex, age, body mass index) were extracted from admission records. General clinical data, including smoking status, diabetes mellitus, surgical interventions, medication use (such as vasoactive medications, hormones, antibiotics, sedatives, analgesics, anticoagulants), hemiplegia, edema (In this study, edema was defined as applying pressure on the patient’s area of suspected edema. If the local skin appears with deep indentation and recovers slowly, it is determined to be edema17.), a incontinence, nutritional therapy, nutrition days, fasting days, days in bed, mechanical ventilation duration, physical restriction duration, length of stay, patient’s state of consciousness (clear, somnolence, stupor, shallow coma, moderate coma, deep coma), and vital signs (maximum body temperature, minimum SPO2and minimum blood pressure recorded during hospitalization; hypotension defined as systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure < 60 mmHg), Braden Scale, Barthel Scale, and Glasgow Coma Scale, were retrieved from the hospital information system (HIS). Laboratory tests included lactic acid, creatinine, prealbumin, albumin, hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cells, and red blood cells. All laboratory data were based on initial examinations following admission to the neurosurgery department.

Data management

The quality and completeness of the reported data were rigorously checked. Missing values, extreme values, or implausible entries were referred back to the data collectors for review. If uncertainties remained, the principal investigator made the final decision on study inclusion through mutual agreement. Missing values that were deemed to meet the inclusion criteria were statistically imputed, while remaining missing values were excluded from the analysis.

Endpoints

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of HAPI, assessed according to the criteria established by the NPIAP in 20191.

Stage 1 Pressure Injury: Intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema.

Stage 2 Pressure Injury: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis.

Stage 3 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin loss.

Stage 4 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin and tissue loss.

Unstageable Full-Thickness Pressure Injury: Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss.

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: Persistent nonblanchable deep red, maroon, or purple discoloration.

The designated primary care nurse, who was responsible for the patient’s daily care, observed, assessed, and recorded the skin condition of the patient’s pressure sites daily. Upon identifying a HAPI, the diagnosis was confirmed and the stage of the PI was determined by certified wound care specialists. To ensure the accuracy of the diagnosis and staging, the researchers and wound care experts jointly re-evaluated the findings. In cases of disagreement, a third certified wound care specialist was consulted to make the final decision.

Sample size

This study identified 23 potential risk factors. According to the requirements of the Cox regression model, each variable requires 10 times the number of positive events. The literature indicates that the incidence of PI in neurosurgery is 20.2%19. Therefore, the required sample size was calculated as 23 × 10 ÷ 0.202 = 1138.6, approximately 1139 cases. Ultimately, we collected 1192 samples, and after excluding those that did not meet the criteria, 1165 cases were included in the final analysis.

Data analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (mean (SD)) if they followed a normal distribution, as determined by histogram and Shapiro-Wilk test. Data that did not conform to a normal distribution were expressed as median and interquartile range (median [IQR]). Categorical data were presented as number of cases and percentage (n (%)).

Incidence density and cumulative incidence were calculated using the following formulas:

Incidence density (per patient-day) = number of neurosurgery inpatients with PI/total number of follow-up days for neurosurgery inpatients.

Cumulative incidence (%) = number of neurosurgery inpatients with PI/total number of neurosurgery inpatients in the sample × 100.

If fewer than 20% of values were missing, multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) was used to fill in the missing variables. Predictive mean matching was applied to impute continuous data, while logistic regression was employed for binary data. Next, a univariate Cox regression model was employed to identify risk factors associated with HAPI in neurosurgical inpatients. Variables that showed statistical significance in the univariate analysis were then included in a backward stepwise Cox regression model for multivariate analysis, aiming to determine the independent risk factors of HAPI in neurosurgical inpatients (α = 0.05, β = 0.10). All reported p-values were two-sided, with a significance level set at 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using R statistical software (version 4.3.2), with the following R packages utilized: mice, tableone, survival, and broom.

Ethical considerations

This study adhered to the ethical principles stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and has received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Zhongjiang County People’s Hospital (Ethics Approval No.: JLS-2023-001). Patients with capacity or their legal representatives provide voluntary participation in clinical trials and signed the informed consent.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the study period, 1192 patients were admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery. Of these, 13 were excluded because they were younger than 18 years, and 14 were excluded due to more than 80% of their data being missing, resulting in a final cohort of 1165 patients (Fig. 1). Lactic acid and prealbumin were excluded from the analysis because their missing rates were 89.9% and 80.2%, respectively. The mean age of the patients was 67.0 years (interquartile range, 54.0 to 74.0); 463 (39.7%) were female. The mean length of stay was 10.0 days (interquartile range, 5.0 to 17.0). Detailed patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Occurrence and distribution characteristics of HAPI

During the study period, a total of 54 HAPIs were recorded in 42 patients; 34 patients had 1 HAPI, 4 patients had 2 HAPIs, and 4 patients had 3 HAPIs. We followed up with neurosurgical inpatients for a total of 14,091 patient-days, resulting in an incidence density of 0.003 HAPIs per patient-day and a cumulative incidence of 3.6%. The most common sites of neurosurgical HAPIs were the buttocks (20 cases, 37%) and the sacral region (13 cases, 24.1%), and the most common stages were stage 1 (21 cases, 38.9%) and stage 2 (27 cases, 50%) (Table 2).

Risk factors for HAPI-univariate analyses

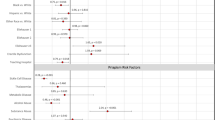

Univariate analysis revealed that the administration of vasoactive medications, antibiotics, and sedatives, as well as hemiplegia, edema, enteral nutrition, fasting days, days in bed, mechanical ventilation duration, physical restriction duration, state of consciousness, maximum body temperature, Braden Scale, Barthel Scale, Glasgow Coma Scale, albumin, and hemoglobin, were significantly associated with the incidence of HAPI (all P < 0.05, Table 3).

Risk factors for HAPI-multivariate analyses

The association between HAPI and potential risk factors was further examined using multivariate Cox regression analysis. The results in Table 4 indicate that edema (HR = 3.50, 95% CI, 1.29 to 9.54; P = 0.014) and albumin (HR = 0.95, 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.00; P = 0.049) were independent risk factors for HAPI in neurosurgery inpatients.

Discussion

Incidence of HAPI in neurosurgery

In this study, the cumulative incidence rate of HAPI in neurosurgery inpatients was 3.6%, which is significantly lower than the 20.2% reported by Mustafa Qazi in his study18. This discrepancy is likely attributable to differences in economic conditions and medical standards across regions. A meta-analysis on the epidemiology of HAPI reported a global incidence of 8.4%, with the incidence in Asia being 3.0% (95% CI, 2.0 to 4.1)4. Another study on the prevalence of HAPI in Chinese ICU patients reported an incidence of 4.31%6. The study was conducted in a grade A tertiary hospital in China, consistent with previous research findings and of significant reference value. HAPIs typically develop at bony prominences or in areas where the skin is in contact with medical devices1. According to existing reports19,20,21the most common sites of HAPIs include the sacral region, heel, ischium, and the region above the greater trochanter of the femur; notably, approximately 75% of pressure injuries are located around the pelvic girdle, reflecting the distribution of pressure in both supine and sitting positions. The study by Alshahrani et al., conducted in an intensive care environment, also confirmed that the sacrum, coccyx, buttocks, and ischium are high-incidence areas for PIs, accounting for 44.8% of all cases22. In this study, HAPI was mainly found in the buttocks (37%) and the sacral region (24.1%). This finding fits with Vandenkerkhof et al.23. on the coccyx sacrum (27%) and Imet al.24 on the coccyx (39.3%). The reason can be attributed to the traumatic brain injury (TBI) and other severe neurosurgery patients in the process of treatment, or due to physical disability to take the head and trunk suspension straight sitting posture, resulting in the sacral caudal area to bear greater pressure20. Many severely ill patients with neurological conditions have relatively low levels of awareness, perception, and mobility. Impairment of consciousness reduces sensory perception and motor capacity and causes the patient to increase the risk of HAPI by three to six times25. In this study, the majority of HAPIs were classified as stage 2 (50%) and stage 1 (38.9%), consistent with a systematic review of patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, in which stage 2 was the most frequently reported (52.6% and 51.5%)17.

Risk factors for HAPI in neurosurgery

In this study, 42 patients developed a total of 54 HAPIs. We systematically identified and analyzed 36 potential risk factors associated with the development of HAPIs. The results of univariate analysis revealed correlations between the occurrence of HAPIs and the administration of vasoactive medications, antibiotics, and sedatives, as well as conditions such as hemiplegia, edema, enteral nutrition, fasting days, days in bed, mechanical ventilation duration, physical restriction duration, state of consciousness, maximum body temperature, and assessments including the Braden Scale, Barthel Scale, Glasgow Coma Scale, albumin, and hemoglobin levels. These findings are corroborated by multiple studies20,26,27,28. By multivariate COX regression analysis, edema (HR = 3.50, 95% CI, 1.29 to 9.54; P = 0.014) and albumin (HR = 0.95, 95% CI, 0.90 to 01.00; P = 0.049) were independent risk factors for HAPI in neurosurgical patients, consistent with the findings of Reese29 and Cheng30. In the pathogenesis of PIs, inflammation and edema are interrelated physiological processes that occur in the context of tissue damage induced by sustained mechanical pressure31. Neurogenic inflammation is frequently observed in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke32. During this period, the liver’s remodeling function triggers a marked increase in acute-phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A, while the synthesis of visceral proteins, including albumin and prealbumin, is concomitantly reduced. This shift results in a decreased serum albumin concentration33. Albumin, a critical plasma protein, serves not only as a transporter of nutrients but also plays a vital role in maintaining osmotic pressure balance and providing antioxidant defense34. The study revealed that systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is an independent predictor of poor outcome in patients with cerebral hemorrhage and is tightly associated with albumin levels. Approximately 40% of SIRS patients also exhibit low protein levels35. As an indicator of the inflammatory response, low serum albumin levels compromise plasma osmotic balance, leading to interstitial fluid extravasation, subsequent edema, and increased risk of PIs36,37. Research conducted by Serra et al.38. has further substantiated that albumin supplementation significantly lowers the incidence of PIs in patients within intensive care settings. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring edema and serum albumin levels, as early intervention through inflammation control and albumin supplementation may help prevent PIs. The economic implications are substantial. An observational study conducted in Sichuan Province, China, found that patients with pressure injuries had a median hospital stay of 20 days and incurred median costs of ¥8,039.12. In contrast, patients without complex wounds had a median stay of 7 days and median costs of ¥3,337.1639. These figures suggest that PIs may lead to nearly threefold increases in both length of hospitalization and healthcare expenditures. As both hypoalbuminemia and edema are modifiable risk factors, their early identification and management could significantly reduce not only clinical complications but also the financial burden on patients and the healthcare system.

Limitations

Although this was a large-scale prospective cohort study, its single-center design at a grade A tertiary hospital in western China limits the generalizability of the findings. Variations in healthcare delivery models, resource availability, clinical practice standards, and patient demographics across regions and hospital tiers may influence the incidence and risk factors of HAPIs. For example, patients in lower-tier hospitals may be at higher risk due to limited access to advanced medical equipment, reduced staffing levels, and less frequent implementation of standardized preventive protocols. In non-Asian healthcare settings, variations in cultural practices, healthcare delivery models, and patient case mix, could also influence both the occurrence and management of PIs. Compared with multi-center studies, our findings may be more reflective of high-resource neurosurgical units. To enhance external validity, future research should include multi-center studies encompassing diverse geographic and institutional contexts. Due to limitations in medical insurance coverage, lactic acid and prealbumin levels were not routinely tested, resulting in substantial missing data (89.9% and 80.2%, respectively). As a result, these potentially important biochemical markers were excluded from the final analysis, which may have limited the comprehensiveness of our risk factor assessment. Considering this limitation, future studies incorporating more complete datasets, ideally from centers with broader access to laboratory testing, are recommended to validate and extend our results. Although this study focused on PIs over bony prominences, MDRPIs were not included in the analysis. This decision was made to maintain consistency in staging criteria and risk factor evaluation, as MDRPIs often involve mucosal membranes or irregular skin surfaces for which the standard staging system is not applicable. However, we acknowledge that the exclusion of MDRPIs may have underestimated the overall burden of HAPIs in neurosurgical patients. Future studies should consider MDRPIs as a distinct category, with appropriate classification methods and prevention strategies tailored to device-related risks. Although all nursing staff involved in this study received standardized training and competency assessment for edema evaluation, which was part of routine clinical practice, we did not perform a formal statistical assessment of inter-rater reliability. This may limit the ability to fully account for potential variability in subjective assessments.

Conclusion

This study provides critical insights into the incidence and risk factors associated with HAPI among neurosurgical inpatients. The incidence density of HAPI was 0.003 per patient-day, with a cumulative incidence of 3.6%. Predominantly affecting the buttocks and sacral region, HAPI primarily manifested in stages 1 and 2. In our final survival multivariate analysis, edema and albumin emerged as independent risk factors for HAPI in neurosurgical inpatients. These findings emphasize the importance of monitoring edema and albumin levels, and underscore the role of timely inflammation control and albumin supplementation in mitigating the risk of PI.

Data availability

Data available on request from the authors; The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ed., E. H. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance.Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. 3Rd Ed. Osborne Park, Australia: Cambridge Media;. (2019).

Gaspar, S., Peralta, M., Marques, A. & Budri, A. Gaspar de matos, M. Effectiveness on Hospital-Acquired pressure ulcers prevention: A systematic review. Int. Wound J. 16, 1087–1102 (2019).

Afaneh, T., Abu-Moghli, F. & Mihdawi, M. Identifying Nursing-Sensitive indicators for hospitals: A modified Delphi approach. Cureus 16, e59472 (2024).

Li, Z., Lin, F., Thalib, L. & Chaboyer, W. Global prevalence and incidence of pressure injuries in hospitalised adult patients: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 105, 103546 (2020).

VanGilder, C., Lachenbruch, C., Algrim-Boyle, C. & Meyer, S. The international pressure ulcer prevalence™ survey: 2006–2015: A 10-Year pressure injury prevalence and demographic trend analysis by care setting. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 44, 20–28 (2017).

Lin, F. F. et al. Pressure injury prevalence and risk factors in Chinese adult intensive care units: A Multi-Centre prospective point prevalence study. Int. Wound J. 19, 493–506 (2022).

Mervis, J. S. & Phillips, T. J. Pressure ulcers: pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 81, 881–890 (2019).

Nghiem, S., Campbell, J., Walker, R. M., Byrnes, J. & Chaboyer, W. Pressure injuries in Australian public hospitals: A cost of illness study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 130, 104191 (2022).

Padula, W. V. et al. Value of hospital resources for effective pressure injury prevention: A Cost-Effectiveness analysis. Bmj Qual. Saf. 28, 132–141 (2019).

Bauer, K., Rock, K., Nazzal, M., Jones, O. & Qu, W. Pressure ulcers in the united states’ inpatient population from 2008 to 2012: results of a retrospective nationwide study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 62, 30–38 (2016).

Padula, W. V. & Delarmente, B. A. The National cost of Hospital-Acquired pressure injuries in the united States. Int. Wound J. 16, 634–640 (2019).

Wassel, C. L., Delhougne, G., Gayle, J. A., Dreyfus, J. & Larson, B. Risk of readmissions, mortality, and hospital-Acquired conditions across hospital-Acquired pressure injury (Hapi) stages in a Us National hospital discharge database. Int. Wound J. 17, 1924–1934 (2020).

Jansen, R., Silva, K. & Moura, M. Braden scale in pressure ulcer risk assessment. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 73, e20190413 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Predictive validity of the Braden scale for pressure injury risk assessment in adults: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Open. 8, 2194–2207 (2021).

Kottner, J., Black, J., Call, E., Gefen, A. & Santamaria, N. Microclimate: A critical review in the context of pressure ulcer prevention. Clin. Biomech. 59, 62–70 (2018).

Ribeiro, R. N., Oliveira, D. V. D., Paiva, W. S., Sousa, R. M. C. & Vieira, R. D. C. A. Incidence of pressure injury in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Bmj Open. 14, e89243 (2024).

Trayes, K. P., Studdiford, J. S., Pickle, S. & Tully, A. S. Edema: diagnosis and management. Am. Fam Physician. 88, 102–110 (2013).

Qazi, M., Khattak, A. F. & Barki, M. T. Pressure ulcers in admitted patients at a tertiary care hospital. Cureus 14, e24298 (2022).

Hajhosseini, B., Longaker, M. T. & Gurtner, G. C. Pressure injury. Ann. Surg. 271, 671–679 (2020).

Yoon, J. E. & Cho, O. H. Risk factors associated with pressure ulcers in patients with traumatic brain injury admitted to the intensive care unit. Clin. Nurs. Res. 31, 648–655 (2022).

Labeau, S. O. et al. Prevalence, associated factors and outcomes of pressure injuries in adult intensive care unit patients: the decubicus study. Intensive Care Med. 47, 160–169 (2021).

Alshahrani, B., Middleton, R., Rolls, K. & Sim, J. Pressure injury prevalence in critical care settings: an observational Pre-Post intervention study. Nurs. Open. 11, e2110 (2024).

VanDenKerkhof, E. G., Friedberg, E. & Harrison, M. B. Prevalence and risk of pressure ulcers in acute care following implementation of practice guidelines: annual pressure ulcer prevalence census 1994–2008. J. Healthc. Qual. 33, 58–67 (2011).

Im, M. & Sook, H. A. Study on the pressure ulcers in neurological patients in intensive care units. J. Korean Acad. Fundamentals Nurs. 13, 190–199 (2006).

Kwak, H. R. & Kang, J. Pressure ulcer prevalence and risk factors at the time of intensive care unit admission. Sŏngin Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 27, 347 (2015).

McEvoy, N. et al. Effects of vasopressor agents on the development of pressure ulcers in critically ill patients: A systematic review. J. Wound Care. 31, 266–277 (2022).

Liao, X. et al. Risk factors for pressure sores in hospitalized acute ischemic stroke patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 28, 2026–2030 (2019).

Lima, S. M., González, M. M., Carrasco, C. F. & Lima, R. J. Risk factors for pressure ulcer development in intensive care units: A systematic review. Med. Intensiv. 41, 339–346 (2017).

Reese, T. J. et al. Implementable prediction of pressure injuries in hospitalized adults: model development and validation. Jmir Med. Inf. 12, e51842 (2024).

Cheng, H. et al. Risk factors and the potential of nomogram for predicting Hospital-Acquired pressure injuries. Int. Wound J. 17, 974–986 (2020).

Edwards, S. L. Tissue viability: Understanding the mechanisms of injury and repair. Nurs. Stand. 21, 48–56 (2006).

Sorby-Adams, A. J., Marcoionni, A. M., Dempsey, E. R., Woenig, J. A. & Turner, R. J. The role of neurogenic inflammation in Blood-Brain barrier disruption and development of cerebral oedema following acute central nervous system (Cns) injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1788 (2017).

Evans, D. C. et al. The use of visceral proteins as nutrition markers: an Aspen position paper. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 36, 22–28 (2021).

Caironi, P. & Gattinoni, L. The clinical use of albumin: the point of view of a specialist in intensive care. Blood Transf. 7, 259–267 (2009).

Di Napoli, M. et al. Hypoalbuminemia, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and functional outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Crit. Care. 41, 247–253 (2017).

Serra, R. et al. Low serum albumin level as an independent risk factor for the onset of pressure ulcers in intensive care unit patients. Int. Wound J. 11, 550–553 (2014).

Van Damme, N. et al. Physiological processes of inflammation and edema initiated by sustained mechanical loading in subcutaneous tissues: A scoping review. Wound Repair. Regen. 28, 242–265 (2020).

Serra, R. et al. Albumin administration prevents the onset of pressure ulcers in intensive care unit patients. Int. Wound J. 12, 432–435 (2015).

Jiang, Q., Dumville, J. C., Cullum, N., Pan, J. & Liu, Z. Epidemiology and disease burden of complex wounds for inpatients in china: an observational study from Sichuan Province. Bmj Open. 10, e39894 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to Ya Yin, Heng Li, Yang Liu, and Juan Zhang from the People’s Hospital of Zhongjiang County for their contributions to the data collection endeavors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Medical Youth Innovation Research Project (Grant No. Q22096); and the Deyang City Key Research and Development Guidance Project in the field of social development (Project No. 2023SZZ119).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D., M. L. and C.W. wrote the main manuscript text. Y.D. was responsible for the statistical analysis of the study and prepared all the figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Y., Liu, M., Wang, C. et al. Risk factors for hospital-acquired pressure injury in neurosurgery inpatients: a real-world prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 29327 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15648-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15648-8