Abstract

The caregiver-patient dynamic is a complex relationship. While caregivers’ potential psychological and physical burdens have received much attention, few studies have focused on the patient’s perspective. This study investigated how the presence of a caregiver affects perceived stress, mental health and metabolic function in individuals with physical disabilities (PDis). The study included individuals with a PDis living with a full-time caregiver and those with a PDis living alone. The severity of perceived stress, the state of mental health, and the amount of social support were assessed using standardized questionnaires. Urine samples were collected and analyzed using a proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy-based metabolomics approach to investigate if different living situations affect biochemical pathways. Although there were no statistically significant differences in stress outcomes or mental health between the two groups, metabolomic analysis revealed a significant impact of the living situation on metabolic pathways, including histidine metabolism and alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism. Aspartic acid levels positively correlated with perceived stress and depressive symptoms in the Caregiver Group, while inosine positively correlated with stress in the Alone Group. This study highlights the unique psychological and metabolic profiles associated with a PDis based on living arrangements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The caregiver-patient dynamic is a complex relationship. Patients who require a caregiver may need support with daily tasks such as cleaning, dressing, cooking, and transportation, or even full-time support, wherein the client relies on homecare caregivers who often live with these patients. Caregivers may be family members, supportive roommates, or several assigned formal paid homecare caregivers who rotate shifts. It was reported that 49.5% of individuals with a disability of any kind rely on either formal or informal family homecare caregivers1. The relationship between caregiver and patient can be multifaceted, depending on whether the caregiver is a family member or hired, the compatibility of personalities, the level of care needed, and the possibility of communication difficulties. When an individual with a physical disability (PDis) requires a caregiver for extended periods or full-time, it is reasonable to expect that the relationship between the patient and the caregiver has a direct emotional, social, and physical impact on both individuals.

Most previous research regarding the caregiver-patient relationship has been directed toward the caregiver’s mental health, stress, and social support systems2. Earlier studies have shown that the emotional weight that comes with being a caregiver often negatively impacts their mental health, wherein caregivers of individuals with PDis may perceive higher levels of distress and adverse mental health symptoms3,4. To fully appreciate the dynamics of the caregiver-patient dyad, however, it is critical to also consider the patient’s perspective, as living with a PDis can significantly impact the quality of life, adding challenges to daily tasks and potentially leading to social exclusion5. Individuals with cerebral palsy (CP), stroke, or spinal cord injury (SCI) have recorded an increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes such as increased depression and anxiety symptoms6,7,8. Those with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (AMC), however, have not been found to have a higher risk of adverse mental health outcomes9,10. Additionally, perceived psychological stress has been linked closely to mental health. In general, those with PDis recorded higher perceived stress levels than the general population11,12,13, and those with PDis who exhibit high levels of perceived stress may be particularly vulnerable to accelerated cellular aging14. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the significant health impacts of social isolation15. Specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the ability of individuals with PDis to receive healthcare and negatively impacted their mental well-being while also possibly increasing vulnerability to stress16,17,18.

In caregiver-patient relationships, few studies have assessed the patient’s stress and emotional burden or have attempted to confirm that the availability of a caregiver has a positive psychological impact on the patient’s mental health and perceived stress. Of the limited research in this area, one study showed that mental health among caregivers and their non-PDis adolescent patients is positively correlated19. Factors such as whether the caregiver is a family member or not, the patient’s cognitive and physical capabilities, and the overall workload can dictate the quality of the relationship between caregiver and patient20. The lack of data in this realm limits how healthcare personnel and policymakers may maximize this relationship. Additionally, a limited understanding exists of how living alone impacts individuals with PDis. Non-PDis individuals who live alone are at a higher risk of suicide and musculoskeletal disorder (sarcopenia) compared to individuals who live with others21,22. Addressing these gaps may benefit from integrating biological data, such as metabolomics, which comprehensively analyzes biological functions. Metabolomic profiles can objectively quantify biological responses to stress in stroke and SCI patients23,24,25,26 and reveal vulnerability to adverse mental health outcomes27,28.

The present study evaluated the emotional and biopsychosocial well-being of individuals with PDis, focusing on the patient perspective within the caregiver-patient relationship. The study population included individuals who use a wheelchair as their primary mode of transportation, encompassing conditions such as AMC, spastic quadriplegia CP, type 2 SMA, ischemic stroke, and SCI. We hypothesized that individuals with PDis who live with a full-time caregiver would report higher perceived social support and lower levels of adverse mental health symptoms compared to those with PDis who were living alone. Additionally, we expected to identify metabolomic differences between these groups and explore potential metabolomic biomarkers associated with emotional and psychosocial well-being.

Results

The presence of a caregiver and its psychological impact on the patient

Figure 1 shows the results of the questionnaires concerning mental health, stress, resilience, and physical activity levels for individuals with a physical disability (PDis) either living alone (Alone Group) or with a caregiver (Caregiver Group). Higher scores corresponded to higher recorded symptoms for the PSS-10 (Perceived Stress Scale), Analog Stress Scale, PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire Version 9), MDI (Major Depression Inventory), and GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder). In contrast, for the BRS (Brief Resilience Scale) and Godin (leisure-time exercise questionnaire) assessments, higher scores corresponded to higher recorded resilience or physical activity, respectively. None of the questionnaire scores showed a statistically significant difference between groups (all p’s > 0.05), but slight differences were observed in some areas. The Caregiver Group scored higher than the Alone Group regarding the PSS over the last month (p = 0.09). The Analog Stress Scale rated current perceived stress levels on a 1–5 scale at the time of assessment, which revealed similar results for each group. In the PHQ and MDI questionnaires for depressive symptoms, the PHQ screened better for suicidal ideation, and the MDI had more in-depth answer choices. The Caregiver Group recorded a lower PHQ score than the Alone Group but a higher MDI score. In the GAD questionnaire for anxiety symptoms, the Caregiver Group recorded a higher score than the Alone Group. The BRS for resilience was slightly higher for the Alone Group. The Godin score used to measure physical activity was lower for the Caregiver Group.

Mental health, stress, activity levels (Alone n = 8; Caregiver n = 12) and resilience scores (caregiver n = 7, alone n = 7) from indicated questionnaires. Blue bars represent the alone group, and red bars represent the caregiver group. The x-axis represents the questionnaire types, and the y-axis represents the questionnaire score. Depression symptoms were assessed through the Major Depression Inventory (MDI)/Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), anxiety through the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD), and stress-related emotions through the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and Analog Stress Scale. Resilience was assessed via the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) and physical activity levels via the Godin scale. Note the trend for higher perceived stress among individuals in the Caregiver Group. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 2 reveals the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ) scores, broken down into SSQa for appraisal, SSQb for belonging and SSQt for tangible social support. Appraisal refers to social support involving confidence-building, positive feedback, and affirmation. Belonging refers to a sense of social inclusion, the perception of being part of a group or community. Tangible, or instrumental support, involves receiving concrete assistance through financial aid, services, or physical assistance. The higher the score, the greater the perceived social support. None of the results regarding SSQ scores showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups (all p > 0.05). The SSQ scores were similar across all portions of the SSQ, where SSQ total, SSQa, and SSQb all showed lower scores for the Caregiver Group, and SSQt showed a higher score for the Caregiver Group relative to the Alone Group.

Perceived social support (Alone n = 7, Caregiver n = 7). The x-axis represents the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ) sections, and the y-axis represents the SSQ score. Blue bars indicate the Alone Group and red bars indicate Caregiver Group. SSQ total for the accumulated score, SSQa represents appraisal, SSQb represents belonging, and SSQt represents tangible. The error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Figure 3 displays the retrospective PSS data regarding before, during COVID-19 and within the last month to evaluate participants’ perceived stress. COVID-19 was used here as a contextual example of extreme isolation and social disruption for individuals with a PDis. The global average score for the PSS was 13, measured in 1983 (n = 2387)29. None of the differences within the COVID-19 results showed statistical significance (all p’s > 0.05), but some trends were observed. Before COVID-19, perceived stress levels among the Caregiver Group were slightly below those of the Alone Group and the global average. During COVID-19, both groups experienced a sharp increase in perceived stress levels with the Caregiver Group having a slightly higher score than the Alone Group. This increased perceived stress from before to during COVID-19 is conceptualized in the ΔPSS1 bar graph on the right side of Fig. 3B. Perceived stress levels then dropped from during COVID-19 to within the last month (i.e., post-COVID-19) in both groups. The results obtained within the last month showed that the Caregiver Group was close to the global average and similar to the levels observed before COVID-19. By contrast, levels in the Alone Group dropped lower than the global average and the levels before COVID-19. This change from during COVID-19 to the levels reported last month (i.e., post-COVID-19) is conceptualized via ΔPSS2 in Fig. 3B. These retrospective results provide preliminary insight into how periods of extended isolation and social disruption may differentially affect perceived stress among individuals with physical disabilities, depending on caregiver reliance.

Retrospective Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores over three time points (n = 20). The blue dotted line and triangles represent the Alone Group, the red solid line and squares represent the Caregiver Group. The x-axis indicates the PSS time point inquired about in the questionnaire, and the y-axis indicates the PSS score. The mean difference between the PSS score before and during COVID-19 is represented on the right bar graph labelled ΔPSS1, and the difference between the PSS score during COVID-19 and the last month is represented by the rightmost bar graph labelled ΔPSS2. Note the trend for higher perceived stress levels among the Caregiver Group during and after COVID-19. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Urine metabolome differences between caregiver and alone groups

Table 1 displays the most significantly altered metabolites, their chemical shift, p-values and their regulation when comparing the Caregiver and Alone Groups. These 16 unique metabolites were identified out of 385 bins that were deemed significant via Variable Importance Analysis based on random Variable Combination (VIAVC) or Mann-Whitney U (MWU) tests. Of these metabolites, six were found to be upregulated, and ten were found to be downregulated in the Caregiver Group relative to the Alone Group.

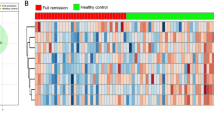

Figure 4 shows multivariate modelling techniques to analyze the metabolomic data across the two groups. Initially, unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to all bins, and then a supervised Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA), which also utilized all bins, failed to meet the criteria for validation during permutation and cross-validation tests. Following these findings, VIAVC bins, identified as significantly altered through multivariate analyses, were used for further modelling. Using the VIAVC bins, the supervised OPLS-DA modelling showed significant separation between the groups, as illustrated in the OPLS-DA scores plot in Fig. 4. The OPLS-DA model explained a large amount of the variation between groups (R²Y = 0.891), showed strong group classification (Q² = 0.755), and passed permutation testing utilizing 2,000-permutations (p < 0.001). These validation metrics suggest that the separation observed was unlikely to be due to random chance and reflected robust metabolic differences between the groups. The Alone and Caregiver Groups clustered distinctly along the primary component (T score), indicating that their metabolic profiles differed substantially when based on the VIAVC metabolites.

OPLS-DA scores plot for urine metabolites found to be statistically significant via VIAVC best subset testing. Red and squares represent the Caregiver Group (n = 11), and blue and triangles represent the Alone Group (n = 9). Each square and triangle represents one participant. The shaded oval regions show the 95% confidence interval for each respective group. The x-axis represents predictive variation (between-group differences), while the y-axis indicates orthogonal variation (within-group variation). The plot also includes measures from cross-validation (Q2) and permutation (R2) testing for the OPLS-DA model.

Figure 5 represents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve that was produced to measure the model’s classification and predictive accuracy. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was 0.971, indicating excellent classification performance. The 95% confidence interval (CI: 0.815–1.0) confirms the robustness of this result, and the predictive accuracy of 88.8% suggests strong potential for generalization. The ROC curve provided complementary validation of model performance, reinforcing the conclusion that metabolomic profiles differed meaningfully between the groups.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve based on the Variable Importance Analysis based on random Variable Combination (VIAVC) best subset bins. The related area under the curve (AUC), 95% confidence interval and the predictive accuracy are specified in the figure. The predictive accuracy is based on 8 VIAVC bins.

Metabolic Pathway Topology Analysis. The x-axis and the size of the circle represent the impact factor, which measures how the identified metabolites influence the given pathway. The y-axis and the colour represent the p-value in -log10; the higher the value, the greater the statistical significance and the darker the colour. The pathways that are less than p = 0.05 are labelled. (1) Histidine metabolism, p = 0.0001, impact = 0.41. (2) beta-Alanine metabolism, p = 0.009, impact = 0. (3) Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, p = 0.01, impact = 0.31. (4) Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, p = 0.02, impact = 0.078. (5) Thiamine metabolism, p = 0.05, impact = 0.

Figure 6 shows the pathway topology analysis results used to investigate potential underlying pathway disruptions that may be present based on the list of metabolites identified as significantly altered by either the MWU or VIAVC tests. The metabolism pathways displayed in order of p-value are histidine (1), beta-alanine (2), alanine, aspartate and glutamate (3), glycine, serine, threonine (4), and thiamine (5) metabolism.

Metabolite levels reflect perceived stress, mental health and physical exercise habits

Correlations between metabolite levels and the questionnaire data are presented in Fig. 7, and all correlates were initially tested for homogeneity of variance to determine the correlation test to apply. None of the data distributions were normal; therefore, the Spearman correlation was calculated for each dataset. For the Caregiver Group, there were positive correlations between aspartic acid/PSS (Rho = 0.882, p = 0.001) and aspartic acid/PHQ (Rho = 0.812, p = 0.01) and negative correlations between l-isoleucine/Godin (Rho=−0.927, p = 0.0001) and 3-hydroxyisovalerate/Godin group (Rho=−0.817, p = 0.01). These significant correlations were not found for the Alone Group. Thus, as levels of perceived stress and depression increased, so did aspartic acid, and a decrease in physical activity was reflected in a decrease in levels of l-isoleucine and isovalerate. A positive correlation between the analog stress scale and inosine was found for the Alone Group (Rho = 0.933, p = 0.001) but not for the Caregiver Group. Thus, in the Alone Group, higher levels of inosine reflected higher levels of perceived stress.

Correlations between metabolites and questionnaire data. The blue dotted line and triangles represent the Alone Group, and the red solid line and squares represent the Caregiver Group. All correlations were found via Spearman’s due to non-parametric data. Both axes are ranked, questionnaire data on the x-axis and metabolite data on the y-axis. For graph A, aspartic acid and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores were found to correlate positively within the Caregiver Group, Rho = 0.882, p = 0.0003. For graph B, aspartic acid positively correlated with Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) scores within the caregiver group, Rho = 0.812, p = 0.002. For graph C, l-isoleucine negatively correlated with Godin Leisure-Time Exercise (Godin) scores within the Caregiver Group, Rho =−0.927, p = 0.00004. For graph D, inosine levels positively correlated with the analog stress scale score within the Alone Group, Rho = 0.933, p = 0.0007. For graph E, 3-hydroxy isovalerate correlated with Godin scores within the Caregiver Group, Rho =−0.817, p = 0.002. For graphs A, B, C, and E, no significant correlations were found for the Alone Group; for graph D, no significant correlation was found for the Caregiver Group. Both axes are ranked in descending order. Asterisks represent significance: * represents a p-value of less than 0.005, and ** represents the Bonferroni corrected 0.0004 p-values based on the total number of comparisons.

Discussion

This proof-of-principle study explored how caregiver presence influences psychological well-being and metabolic function in individuals with physical disabilities (PDis). While no statistically significant differences in questionnaire scores were found between groups, significantly distinct metabolomic profiles suggest underlying physiological differences related to stress and mental health. Specific correlations regarding metabolite levels and questionnaire scores were also found, suggesting that physiological changes may represent sensitive and robust biomarkers of mental well-being and stress.

Mental health, stress and COVID-19 impact

Although no significant group differences were found in perceived stress, depression, anxiety, or resilience, trends suggested that caregiver reliant individuals had higher PSS, MDI, and GAD scores. In contrast, those living alone scored higher on the PHQ, BRS, and physical activity measures. This divergence, particularly between PHQ and MDI, may reflect the different diagnostic scope of the tools and highlights the complexity of assessing depression in individuals with physical disabilities30,31. Retrospective perceived stress scores also indicated that those with caregivers experienced greater stress increases during COVID-19, while those living alone showed greater stress recovery, which may be due to individuals living alone having greater independent autonomy, as higher perceived control is protective against stress32. It is possible that the Caregiver Group’s caregivers experienced heightened stress, similar to other public health workers, and that those being cared for indirectly increased their stress levels via bystander or vicarious stress effects33,34. Of note is the retrospective nature of these data, and it is important to consider that the results may have differed if data collection had occurred longitudinally. Demographic factors, such as higher employment rates and higher education levels among the Alone Group, may also account for the variance in these results. Despite these trends, these observations should be cautiously interpreted while awaiting further investigation in a follow-up study with a larger patient population.

Social support dynamics

The social support results suggested that individuals with a physical disability who live alone may perceive slightly better social support appraisal and a stronger sense of belonging than those with a caregiver; however, the perception of tangible support is slightly higher for those living with a caregiver. Despite these trends, the results were not statistically significant, as the perceived social support differences between groups were minimal. This suggests that social support can be independently cultivated outside caregiving arrangements, consistent with research on older adults who form effective non-familial or caregiver-unrelated support networks35. It is also possible that the questionnaire did not cover the relevant areas of social support provided by caregivers versus other social support networks.

Metabolomic pathway analysis

Metabolomic pathway analysis provides a systems-level perspective on how biological processes are altered under different conditions. This study identifies coordinated shifts in metabolic regulation between individuals living alone and those reliant on caregivers. Because metabolites are the functional outputs of cellular metabolism, changes in their levels may reflect underlying biochemical activity. Significant changes in multiple metabolites from a shared pathway suggests differential pathway regulation, offering insight into the physiological adaptations or stress responses that may underlie group differences.

Pathway analysis revealed specific differentially regulated metabolic pathways among individuals living with caregivers and those living alone, including the histidine metabolism pathway. The upregulation of L-histidine and histamine and the downregulation of aspartic acid in the Caregiver Group suggest substantial metabolic adaptations. Histidine and its derivatives play critical roles in numerous physiological processes, including neurotransmission, immune response, and gastric secretion36. The elevated histamine levels may indicate increased stress or inflammatory responses in the Caregiver Group, potentially reflecting greater psychological and physical demands on these individuals. Previous studies have linked upregulated histidine metabolism to stress and activated pro-inflammatory pathways37,38.

Pathway analysis also indicated that the alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism pathways were affected by the presence of a caregiver. The downregulation of aspartic acid and upregulation of L-histidine in the Caregiver Group highlights differences in amino acid metabolism. Aspartic acid and glutamate are pivotal in energy production and neurotransmitter synthesis39. The observed changes could impact the physiological stress responses and cognitive functions of individuals in the Caregiver Group, potentially leading to increased vulnerability to stress-related disorders40,41. This pathway was also disrupted in serum analysis following SCI and traumatic brain injury patients, suggesting that this pathway may have direct, measurable effects on the nervous system and its regulatory responses to neuronal injuries25,42.

Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism showed a moderate pathway impact and statistical significance. The upregulation of betaine and guanidoacetic acid in the Caregiver Group suggests alterations in methylation processes and creatine synthesis43,44. These metabolites are crucial for cellular energy homeostasis and neurotransmission45. Changes in this pathway may reflect adaptations to the increased physical and mental demands experienced by individuals living with caregivers46.

Correlation of metabolites with questionnaire data

The correlation between metabolite levels and questionnaire scores within each group provided insights into how metabolic profiles might be associated with psychological well-being and physical activity levels. The correlation between aspartic acid and both PSS and PHQ scores within the Caregiver Group indicates that aspartic acid may play a critical role in the stress and depressive states of individuals with PDis who rely on caregivers. Aspartic acid is an important excitatory neurotransmitter and is involved in the urea cycle and energy production, potentially linking it to stress and mood regulation47. Previous research has shown that aspartic acid levels were found to be significantly lower in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) compared to healthy controls, and abnormalities in neurotransmission involving amino acids such as aspartic acid have been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression48,49. The Alone Group did not display this correlation, yet had similar PHQ/MDI scores. Still, this difference could be based on lower PSS scores and the complexity of metabolic responses to different living conditions. The specific nature of stressors, coping mechanisms, and metabolic pathways likely varies between those living with caregivers and those living alone; furthermore, this could diminish the direct influence of aspartic acid on stress and depressive symptoms. Understanding these nuanced differences is crucial for developing tailored interventions that address the unique needs of individuals with PDis in varying living arrangements.

The negative correlation between the Godin score and both l-isoleucine and 3-hydroxyisovalerate within the Caregiver Group indicates that these metabolites may be related to physical activity levels. L-isoleucine is a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) involved in muscle metabolism, and its reduction may reflect increased muscle utilization during physical activity50. 3-Hydroxyisovalerate, a metabolite in the leucine degradation pathway51, also showed a similar correlation and suggests that higher physical activity is linked to increased catabolism of BCAAs, possibly as an adaptive mechanism to meet energy demands52. Previous studies have shown that higher physical activity levels are associated with lower serum levels of isoleucine and leucine53,54. The presence of a caregiver might facilitate higher-intensity physical activities, leading to increased muscle metabolism and energy demands. Higher overall physical activity levels recorded by the Alone Group might reflect a broader range of activities, some of which may not be as metabolically demanding. This variation in activity intensity could result in less pronounced metabolic changes, hence the absence of strong correlations between physical activity and BCAA levels in the Alone Group.

The positive correlation between the analog stress scale score and inosine observed for the Alone Group may reflect the metabolomic impacts of stress on those with PDis who live alone. Inosine is a purine nucleoside that can have neuroprotective effects and is involved in energy metabolism55. The elevated levels of inosine in response to stress might reflect a compensatory mechanism to counteract stress-induced neuronal damage, as its neuroprotective effects have been shown in multiple sclerosis research to improve clinical outcomes, in pulmonary disease patients, where it is related to disturbances in energy metabolism in muscle tissue and in relation to reperfusion following ischemia, reflecting the body’s response to acute cellular stress and damage56,57,58,59. The Alone Group in the present study displayed this correlation, but not the Caregiver Group, even with both groups showing similar analog stress scale scores, which may be due to distinct metabolic adaptations to their living conditions. Thus, inosine’s role in neuroprotection and energy metabolism may be particularly relevant for individuals who manage stress independently without the immediate support of a caregiver. Elevated inosine levels in response to stress reflect a compensatory mechanism that counteracts stress-induced neuronal damage and maintains metabolic balance.

Limitations and future directions

Limitations within the present study include small sample size, use of retrospective data, data collection limited to two different time points, a variety of PDis distributions, and sub-optimal alignment of the two groups, namely incomplete matching of participants by sex, PDis, clinical characteristics, education levels, employment, and socioeconomic status. These group differences, combined with a smaller sample size, increase variability within each group, expanding the possibility of confounding variables within this study. The small sample size limits the study’s statistical power, thus increasing the likelihood of Type II error and reducing the ability to detect subtle group differences. This limitation also affects the external validity of the findings, making it difficult to generalize the results to the broader population of individuals with PDis. In particular, the uneven sex distribution between groups may introduce bias or obscure previously documented sex-specific patterns in stress, mental health, resilience, or metabolomic profiles60,61. The data collection occurring over two different time points also increases the possibility of confounding variables within the metabolomics outcomes and makes the retrospective PSS data further from their designated time points. Another limitation of this study is the lack of direct measurement of physical activity levels, such as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), accelerometer data, or heart rate monitoring. Additionally, ICU mobility scores could have been objectively measured rather than relying solely on self-reported assessments. Future research should consider using shorter or adaptive questionnaires and incorporating response validity items. Based on these limitations, the present study should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating. While the findings offer preliminary insights into potential psychological and metabolomic differences related to caregiver reliance, they require replication and validation in larger, more demographically balanced samples. The conclusions of this study highlight several areas for future research that could enhance the understanding of the metabolic and psychological differences in individuals with PDis based on their living arrangements.

Conclusion

This proof-of-principle study explored the complex relationships between metabolomic profiles, psychological well-being, perceived stress, social support and living arrangements among individuals with a PDis. Key findings indicate significant metabolic differences between individuals living with caregivers and those living alone, particularly in histidine and aspartic acid pathways. These differences suggest that the metabolic adaptations associated with different living conditions may influence stress and depressive states, especially in individuals reliant on caregivers. Despite these metabolic disparities, questionnaire assessments revealed no statistically significant differences in social support, mental health and stress levels between the two groups, although trends suggest that those who live with caregivers might experience higher levels of anxiety and stress. The trend of the COVID-19 lockdown impact on increased perceived stress in those who live with a caregiver further underlines the complex interplay between living arrangements, stress susceptibility and resilience. The pathway analysis revealed possible significant impacts on several pathways, such as histidine metabolism and alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism. These dysregulations can be the focus of potential targeted interventions to address the specific metabolic differences associated with those with PDis across living situations. Correlation analyses between metabolite levels and questionnaire data, as observed in a positive correlation between aspartic acid levels with depression/stress symptoms within the Caregiver Group and a positive correlation between inosine levels with stress symptoms in the Alone Group, provide critical insights into the biochemical foundations of stress and depressive states in PDis individuals while also indicating their potential for possible biomarkers. Thus, this study highlights the importance of a holistic approach to understanding the complex interactions between those with PDis who live with a caregiver versus those who live alone, as well as their psychological well-being and the metabolic and physiological impact of these experiences. If a more extensive study reinforces these findings, developing tailored interventions may address specific needs based on living situations to improve these individuals’ quality of life and overall health.

Methods

All data collection and recruitment methods were approved by the human research ethics board from the University of Alberta (July 6th, 2022, Pro00120950, Health Research Ethics Board - Health Panel) and Fanshawe College (June 27th, 2023, Pro2306121, Fanshawe College Research Ethics Board), all research was performed following relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardian(s) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study participants

Participant recruitment

For this study, 21 individuals with a physical disability (PDis) were recruited from various community organizations, including the Calgary Power Hockey League, Calgary Cerebral Palsy Association, Alberta Cerebral Palsy Sports Association, Spinal Muscular Atrophy Canada, Lethbridge Powerchair Soccer Program, Canadian Electric Wheelchair Hockey Association and via word of mouth. It is worth noting that these individuals did not regularly participate in a powerchair sport for at least six months when data were initially collected. The inclusion criterion was that individuals use a wheelchair as their primary mode of transportation for a period of at least ten years.

Study participants

PDis participants were differentiated by either living with a full-time caregiver (Caregiver Group) or having no caregiver, partner, or roommate (Alone Group). The Caregiver Group included twelve individuals (female n = 2, male n = 10, overall mean age = 34.5 years), and the Alone Group included nine individuals (female n = 1, male n = 8, overall mean age = 32.4 years). PDis participants in the Caregiver Group had relied on full-time caregivers, familial or non-familial, for at least one year. However, participants in this group showed variation in how much assistance they needed. Some individuals needed help with a few tasks, such as transportation (both to and from locations, including assistance in and out of wheelchairs/powerchairs) and food preparation or consumption, to instances where caregiver support was necessary for all activities of daily living, including eating, sleeping, transportation, and communication. Individuals in the Alone Group were included in this study if they had lived independently without the presence of caregivers, family members, partners or roommates for a minimum duration of one year. The PDis patient characteristics between the two groups can be seen in Table 2. This table highlights the patient information within each group, including sample size, age, sex, PDis, mean ICU mobility score, the highest level of education attained, employment, and religiousness. One individual from the Alone Group did not complete the questionnaire besides information regarding PDis, age, and caregiver situation, and a different individual from the Caregiver Group did not supply urine.

Data collection

Questionnaire data and urine samples were collected during a home visit. Data was collected between July and September in the summers of 2022 and 2023. The assessment of psychological distress and mental health utilized self-administered questionnaires. Assistance was provided as needed to complete the questionnaires by reading them out and filling out the form based on the participants’ answers. The individual assisting with the questionnaires only read the questionnaire to the participant, reiterated the participant’s answer to ensure clear communication, answered questions on what specific questions or answers meant, and did not provide feedback when participants gave their answers. Questionnaire completion took approximately 20–40 min, with breaks offered after each questionnaire section was finished.

Questionnaire and urine collection protocols

As seen in Table 3, questionnaires covered a range of domains, including demographics, analog scales, perceived stress, anxiety, depression, exercise, independent mobility, resilience and social support. The sociodemographic questionnaire captured information on age, sex, housing situation, caregiver status, education, employment, religion, the nature of PDis symptoms, and age at diagnosis. Analog scales assessed current stress levels (1–5, from no stress to stress as bad as could possibly be), mental well-being (1–5, from excelled to not well at all), and screen time (from 1 to 13 < hours). Standardized questionnaires of stress and well-being included the following: the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) was used to measure the individual’s relative recorded stress62 and was broken down into three sections: before, during COVID-19 lockdowns, and “over the last month”; the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) assessed depression levels63; the Major Depression Inventory questionnaire (MDI-12), which provided a more detailed exploration of depressive symptoms64,65; the Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire, (GAD-7) assessed anxiety66; the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (Godin) evaluated exercise habits over a typical one-week span64,65; and the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) mobility scale measured participants’ mobility levels67. In addition, after the first round of data collection, the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS-6) for resilience68 and the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ-12) for social support69 were added (n = 14) (Cronbach’s alpha 0.825). SSQ scoring was then broken down into appraisal, belonging and tangible social support. Fasting urine was collected using a sterilized collection cup between 7:00 am and 10:30 am before the participants had breakfast or used the bathroom, and individuals fasted for at least 8 h prior to urine collection. Subsequently, the cup was capped, the collection date and time were recorded, and the sample was promptly frozen at −18 °C and transported within four days to the University of Lethbridge for storage in a −80 °C freezer.

Urine metabolomics

Sample Preparation of Urine: A standardized procedure was followed for all 20 urine samples28. Each microcentrifuge tube received a mixture comprising 160 µL of buffer, 40 µL of 0.02709% w/v D2O containing trimethylsilyl propanoic acid (TSP), and 500 µL of urine. The buffer (pH 7.4 ± 0.05) consisted of a 4:1 ratio of dibasic potassium phosphate (K2HPO4) to monobasic potassium phosphate (KH2PO4) with a concentration of 0.625 M, 3.75 mM of NaN3 as an antimicrobial agent, and 3.75 mM of potassium fluoride (KF). Following vortexing and centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min, 550 µL of the resulting supernatant was transferred to an NMR tube.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired using a 700 MHz Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer (Bruker Ltd., Milton, ON, Canada) employing a 1-D NOESY gradient water suppression pulse sequence. Each urine sample underwent 128 scans, a total acquisition size of 128 k, which was subsequently zero-filled to 256k, and a spectral window of 20.51 ppm. Spectra were automatically phased, baseline corrected, and line-broadened by 0.3 Hz before being exported to MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) for recursive segment-wise peak alignment70 and subsequent binning using Dynamic Adaptive Binning followed by manual correction71. Data were normalized, log-transformed, and Pareto-scaled prior to modelling72, with all spectra referenced to the TSP peak (0.00δ).

Data analysis

In metabolomics analyses, the normality of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, with the result that all bins were non-parametric. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test (MWU) was then used for non-parametric data analysis73, with Bonferroni-Holm correction applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Variable Importance Analysis based on random Variable Combination (VIAVC) identified significantly altered bins for metabolite identification74. Orthogonal Projection to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA), a supervised multivariate test75, was conducted for group comparisons. Multivariate models were validated by double ten-fold cross-validation and permutation testing using 2000 permutations76,77. Metabolite identification utilized Chenomx 8.2 NMR suite software (Chenomx Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada) with the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), followed by pathway topology analysis using Metaboanalyst with human pathway library, hypergeometric test, and relative betweenness utilized78,79,80. Subsequent analyses used SPSS, encompassing parametric and non-parametric tests for hypothesis testing, with correlations analyzed using Pearson’s and Spearman’s methods.

All questionnaires were scored using the standardized methods recommended by the original authors. No additional scoring modifications (e.g., custom composite scores, lie scales, or reverse-coded consistency checks beyond those built into the scales themselves) were applied. This approach ensured consistency with previously validated uses of these tools. Questionnaire analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM, version 27, Armok, NY, USA), where independent t-tests combined with Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances were used to find p-values when comparing means between the two groups. Correlations were analyzed using Pearson or Spearman tests based on homogeneity of variance tests. These tests were conducted across the questionnaire and metabolite data to determine correlations between metabolite levels and questionnaire scores. The relative differences between the three PSS time frames were labelled as follows: ΔPSS1 - the difference between before COVID-19 and during COVID-19; ΔPSS2 - the difference between during COVID-19 and the last month. Bonferroni correction was conducted for the questionnaire data based on the total number of comparisons conducted for each analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to protect sensitive information. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Del Duca, G. F., Thumé, E. & Hallal, P. C. Prevalence and factors associated with home care among older adults. Rev. Saude Publica. 45 (1), 113–120 (2011).

Pinquart, M. & Sörensen, S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging. 18 (2), 250–267 (2003).

Malm-Buatsi, E. et al. Mental health and parenting characteristics of caregivers of children with spina bifida. J. Pediatr. Urol. 11 (2), 65e1–65e7 (2015).

Foster, H. & Elntib, S. Stress and well-being of unpaid carers supporting claimants through disability benefit assessments. Health Soc. Care Community. 28 (5), 1525–1534 (2020).

Morris, J. Social exclusion and young disabled people with high levels of support needs. Crit. Soc. Policy. 21, 161–183 (2001).

Medeiros, G. C. et al. Post-stroke depression: A 2020 updated review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 66, 70–80 (2020).

Schultz, K. R., Mona, L. R. & Cameron, R. P. Mental health and spinal cord injury: clinical considerations for rehabilitation providers. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil Rep. 10 (3), 131–139 (2022).

Cribb, C. F. et al. Mental health, physical activity, and sports among children with cerebral palsy. Child. Care Health Dev. 49 (6), 1104–1111 (2023).

Wohnrade, C. et al. Health-Related quality of life in spinal muscular atrophy patients and their Caregivers-A prospective, Cross-Sectional, Multi-Center analysis. Brain Sci., 13(1), 110 (2023).

Sarveswaran, S., Mortenson, W. B. & Sawatzky, B. Mental health in adults living with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin Med. Genet. 193 (2), 139–146 (2023).

Han, A., Yuen, H. K. & Wilroy, J. D. Exploring associations of psychological inflexibility with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress in individuals living with a spinal cord injury: A cross-sectional study. Rehabil. Psychol. 67 (2), 170–178 (2022).

Jood, K. et al. Self-perceived psychological stress and ischemic stroke: a case-control study. BMC Med. 7 (1), 53 (2009).

Turner, R., Lloyd, D. & Taylor, J. Physical disability and mental health: an epidemiology of psychiatric and substance disorders. Rehabil. Psychol. 51, 214–223 (2006).

Lahav, Y. et al. Shorter telomeres among individuals with physical disability: the moderating role of perceived stress. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 77 (8), 1384–1393 (2022).

Faraji, J. & Metz, G. A. S. Aging, social distancing, and COVID-19 risk: who is more vulnerable and why?? Aging Dis. 12 (7), 1624–1643 (2021).

Lebrasseur, A. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on people with physical disabilities: A rapid review. Disabil. Health J. 14 (1), 101014 (2021).

Steptoe, A. & Di Gessa, G. Mental health and social interactions of older people with physical disabilities in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Public. Health. 6 (6), e365–e373 (2021).

Reber, L. et al. Fear, isolation, and invisibility during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of adults with physical disabilities in marginalized communities in southeastern Michigan in the united States. Disabil. (Basel), 2, 119-130 (2021).

Stratton, K. J. et al. Caretaker mental health and family environment factors are associated with adolescent psychiatric problems in a Vietnamese sample. Psychiatry Res. 220 (1–2), 453–460 (2014).

Del-Pino-Casado, R. et al. Sense of coherence, burden and mental health in caregiving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 242, 14–21 (2019).

Olfson, M. et al. Living alone and suicide risk in the united states, 2008–2019. Am. J. Public. Health. 112 (12), 1774–1782 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. The association of living alone and social isolation with sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 91, 102043 (2023).

Petersson, J. N. et al. Unraveling metabolic changes following stroke: insights from a urinary metabolomics analysis. Metabolites 14 (3), 145 (2024).

Bykowski, E. A. et al. Urinary biomarkers indicative of recovery from spinal cord injury: A pilot study. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 10, 178–185 (2021).

Bykowski, E. A. et al. Identification of serum metabolites as prognostic biomarkers following spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Metabolites 13 (5), 605 (2023).

de Kluiver, H. et al. Metabolomic profiles discriminating anxiety from depression. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 144 (2), 178–193 (2021).

DeBerardinis, R. J. & Thompson, C. B. Cellular metabolism and disease: what do metabolic outliers teach us? Cell 148 (6), 1132–1144 (2012).

Heynen, J. P. et al. Urinary (1)H NMR metabolomic analysis of prenatal maternal stress due to a natural disaster reveals metabolic risk factors for Non-Communicable diseases: the QF2011 Queensland flood study. Metabolites, 13(4), 579 (2023).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24 (4), 385–396 (1983).

Bech, P. et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J. Affect. Disord. 66 (2–3), 159–164 (2001).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (9), 606–613 (2001).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55 (1), 68–78 (2000).

Bryant-Genevier, J. et al. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, Post-Traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic - United states, March-April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 70 (26), 947–952 (2021).

Guitar, N. A. & Molinaro, M. L. Vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress in health care professionals. Univ. Western Ont. Med. J. 86 (2), 42–43 (2017).

Torres, S. Aging alone, gossiping together: older adults’ talk as social glue. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 74 (8), 1474–1482 (2019).

Brosnan, M. E. & Brosnan, J. T. Histidine metabolism and function. J. Nutr. 150, 2570S–2575S (2020).

Joseph, D. R. et al. Characterization and expression of the complementary DNA encoding rat histidine decarboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87 (2), 733–737 (1990).

Hirasawa, N. Expression of histidine decarboxylase and its roles in inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (2), 376 (2019).

Reitzer, L. Biosynthesis of glutamate, aspartate, asparagine, L-Alanine, and D-Alanine. EcoSal Plus. 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.3 (2004).

Popoli, M. et al. The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 22–37 (2011).

Engskog, M. et al. β-N-Methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) perturbs alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism pathways in human neuroblastoma cells as determined by metabolic profiling. Amino Acids. 49, 905–919 (2017).

Bykowski, E. A. et al. Blood-Derived metabolic signatures as biomarkers of injury severity in traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. Metabolites 14 (2), 105 (2024).

Marie Joncquel-Chevalier, C. et al. Creatine biosynthesis and transport in health and disease. Biochimie 119, 146–165 (2015).

Tachikawa, M. et al. Distinct cellular expressions of creatine synthetic enzyme GAMT and creatine kinases uCK-Mi and CK-B suggest a novel neuron–glial relationship for brain energy homeostasis. Eur. J. Neurosci., 20, 144–160 (2004).

Marques, E. P. et al. Cross-talk between Guanidinoacetate Neurotoxicity, Memory and Possible Neuroprotective Role of Creatine (Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease, 2019).

Oudman, I., Joseph, F. C. & Brewster, L. The effect of the creatine analogue Beta-guanidinopropionic acid on energy metabolism: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 8, e52879 (2013).

Birken, D. L. & Oldendorf, W. H. N-acetyl-L-aspartic acid: a literature review of a compound prominent in 1H-NMR spectroscopic studies of brain. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 13 (1), 23–31 (1989).

Fu, X. Y. et al. [Alterations of plasma aspartic acid, Glycine and asparagine levels in patients with major depressive disorder]. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 41 (2), 132–138 (2012).

Salvadore, G. et al. An investigation of amino-acid neurotransmitters as potential predictors of clinical improvement to ketamine in depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15 (8), 1063–1072 (2012).

Kota, F. et al. Metabolic profiling of total physical activity and sedentary behavior in Community-Dwelling men. PLoS ONE, 11, e0164877 (2016).

Berg, L. et al. Biochemical characterisation and whole genome expression profiling of cultured skin fibroblasts from two South African adults with urinary 3-Hydroxyisovaleric acid and 3-Methylcrotonylglycine. J. Rare Disorders: Diagnosis Therapy, 2, 379-385 (2016).

Sureda, A. et al. l-Citrulline-malate influence over branched chain amino acid utilization during exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 110, 341–351 (2010).

Brodan, V. et al. Changes of free amino acids in plasma of healthy subjects induced by physical exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 35, 69–77 (1976).

Xiaobo, Z. et al. Association of leisure time physical activity and NMR-detected Circulating amino acids in peripubertal girls: A 7.5-year longitudinal study. Sci. Rep., 7, 14026 (2017).

Srinivasan, S. & Torres, A. G. and L. Ribas de pouplana, Inosine in biology and disease. Genes (Basel), 12(4), 600 (2021).

Spitsin, S. et al. Inactivation of peroxynitrite in multiple sclerosis patients after oral administration of inosine May suggest possible approaches to therapy of the disease. Multiple Scler. J. 7 (5), 313–319 (2001).

Pouw, E. M. et al. Elevated inosine monophosphate levels in resting muscle of patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 157 (2), 453–457 (1998).

Fox, A. C. et al. Release of nucleosides from canine and human hearts as an index of prior ischemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 43 (1), 52–58 (1979).

Szabó, G. et al. Effects of inosine on reperfusion injury after heart transplantation. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 30 (1), 96–102 (2006).

Labaka, A. et al. Biological sex differences in depression: A systematic review. Biol. Res. Nurs. 20, 383–392 (2018).

Stroud, J. E. et al. Longitudinal metabolomic profiles reveal sex-specific adjustments to long-duration spaceflight and return to Earth. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79 (11), 578 (2022).

Camargo, L. et al. GAD-7 generalised anxiety disorder scale in Colombian medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: construct validity and reliability. Rev. Colomb Psiquiatr. (Engl Ed). 52 (3), 245–250 (2023).

Kroenke, K. et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (5), 317–325 (2007).

Sikes, E. M. et al. Use of the Godin leisure-time exercise questionnaire in multiple sclerosis research: a comprehensive narrative review. Disabil. Rehabil. 41 (11), 1243–1267 (2019).

Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time physical activity questionnaire. Health Fit. J. Can. 4 (1), 18–22 (2011).

Simon, P. D. The 10-item perceived stress scale as a valid measure of stress perception. Asia Pac. Psychiatry. 13 (2), e12420 (2021).

Tipping, C. J. et al. The ICU mobility scale has construct and predictive validity and is responsive. A multicenter observational study. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 13 (6), 887–893 (2016).

Julian, M. et al. Resilience resources scale: A brief resilience measure validated with undergraduate students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 70 (5), 1434–1443 (2022).

İnan-Budak, M. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the social support questionnaire for transactions in Turkish gender-based violence sample. Arch. Psychiatr Nurs. 45, 184–191 (2023).

Veselkov, K. A. et al. Recursive segment-wise peak alignment of biological 1H NMR spectra for improved metabolic biomarker recovery. Anal. Chem. 81 (1), 56–66 (2009).

Anderson, P. E. et al. Dynamic adaptive binning: an improved quantification technique for NMR spectroscopic data. Metabolomics 7, 179–190 (2011).

Craig, A. et al. Scaling and normalization effects in NMR spectroscopic metabonomic data sets. Anal. Chem. 78 (7), 2262–2267 (2006).

Goodpaster, A. M., Romick-Rosendale, L. E. & Kennedy, M. A. Statistical significance analysis of nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabonomics data. Anal. Biochem. 401 (1), 134–143 (2010).

Yun, Y. H. et al. Informative metabolites identification by variable importance analysis based on random variable combination. Metabolomics 11, 1539–1551 (2015).

Worley, B. & Powers, R. Multivariate analysis in metabolomics. Curr. Metabolomics. 1 (1), 92–107 (2013).

Szymanska, E. et al. Double-check: validation of diagnostic statistics for PLS-DA models in metabolomics studies. Metabolomics 8. S3–S16, (2012).

Westerhuis, J. A. et al. Assessment of PLSDA cross validation. Metabolomics 4, 81–89 (2008).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB: a knowledgebase for the human metabolome. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (suppl_1), D603–D610 (2009).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB 3.0—the human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (D1), D801–D807 (2012).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB: the human metabolome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (suppl_1), D521–D526 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the individuals who participated in this study. We are grateful to Vincent Weiler for technical assistance with the metabolomics assays and Nasrin Soltanpour for assistance with sample collection and preparation. In addition, we thank the University of Lethbridge for the use of the Magnetic Resonance Facility, which provided access to and training on the NMR spectrometer.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant #05628 to GM. CP was also supported by an Alberta Innovates Summer Research Award and by the Canada Graduate Scholarships - Master’s Program (Canadian Institutes of Health Research).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP, TM and GM conceptualized and designed the study. CP acquired ethics approval, pursued participant recruitment, data collection, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. JF assisted with study design, ethics application, data collection and data analyses. JD assisted with ethics application, data collection and manuscript preparation. JL assisted with participant recruitment and data analyses. TM guided the metabolomic analyses and assisted with manuscript preparation. GM provided supervision and funding, assisted with ethics application, guided the data collection and data analysis and assisted with manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petruska, C., Faraji, J., Doan, J. et al. Psychological and physiological differences related to supportive living situations amongst individuals with physical disabilities. Sci Rep 15, 29927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15893-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15893-x