Abstract

The prompt diagnosis of pulmonary infections with unknown etiology in patients in severe condition remains a challenge due to the lack of rapid and effective diagnostic methods. While metatranscriptomic sequencing offers a powerful approach, its clinical utility is often limited by issues of timeliness. In this study, we conducted metatranscriptomic sequencing on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collected from critically ill, severely ill, and ICU patients. Based on microbial detection results, patients were classified into four types: negative, bacterial infection, viral infection, and fungal infection. To identify host gene expression signatures associated with infection, we screened characteristic genes from human metatranscriptomic data by comparing 70% of patients with confirmed infections vs. non-infections. Leveraging these characteristic genes, we constructed classification sub-models employing 13 types of machine learning algorithms, and we further integrated these sub-models into stacking-based ensemble models with Lasso regression, resulting in diagnostic models that required only a small set of gene expression inputs. The average performance of five-fold cross-validation demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy: distinguishing infection from non-infection (AUC = 0.984), bacterial infection from non-bacterial infection (AUC = 0.98), and viral infection from non- viral infection (AUC = 0.98). Test cohorts’ results demonstrated the method’s high diagnostic accuracy consistency with metatranscriptomic sequencing in discerning patient infection status (AUC = 0.865) and the type of infection (viral: AUC = 0.934, bacterial: AUC = 0.871). Our study presented a rapid and inexpensive adjunctive diagnostic strategy that achieves diagnostic accuracy comparable to metatranscriptomic sequencing, enabling timely identification of both infection status and type in pulmonary infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a vital organ for gas exchange between the human body and the external environment, the lungs are highly susceptible to infection due to various factors, including microbial invasion, environmental exposure, and iatrogenic causes. However, the histopathological features of pulmonary infections, such as inflammatory infiltration and tissue necrosis, often closely resemble those of non-infectious diseases, posing a significant diagnostic challenge for surgical pathologists. Failure to establish a timely and accurate diagnosis may lead to disease progression, including pulmonary fibrosis or even systemic dissemination to other organs. In severe cases, patients can rapidly deteriorate into respiratory failure or sepsis, ultimately resulting in death1. Therefore, timely and precise diagnosis, followed by targeted intervention, is critical for improving clinical outcomes.

Patients with severe illness, critical condition, and those admitted to the ICU frequently often face life-threatening pulmonary infections of undetermined etiology, posing major diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in clinical management2,3. While conventional methods for detecting pulmonary infections encompass physical examinations, imaging studies, microbial cultures, and blood tests, they are encumbered by issues such as low specificity, delays, restricted detection capabilities, and intricate operational procedures4,5. In the absence of a confirmed diagnosis, empirical therapy predominates, typically involving the combination use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, antiviral agents, and/or antifungal drugs. This approach is associated with considerable costs, lacks specificity, and contributes to antibiotic misuse, drug resistance, and potential adverse effects3.

In recent years, metagenomic sequencing has emerged as a promising strategy for diagnosing pulmonary infections6,7. Both metagenomic and metatranscriptomic detection technologies offer substantial improvements in detection accuracy8 and microbial spectrum coverage including bacteria9 viruses10 and fungi, thereby enabling personalized treatment11. Nonetheless, these techniques present notable limitations, including data analysis complexity, and the necessity for specialized knowledge and skills, resulting in prolonged turnaround times for results12. These limitations could result in the oversight of optimal treatment opportunities for patients with severe illness, critical conditions, and those admitted to the ICU. Consequently, the development of rapid and inexpensive diagnostic approaches with diagnostic precision akin to metagenomic sequencing, capable of discerning infection status and type, assumes paramount importance. Such advancements would be pivotal in guiding timely, targeted antibiotic, antiviral, or antifungal interventions for these patients. This not only can significantly decrease drug selection pressure and adverse drug reactions, but also contribute to improving patient outcomes.

To address this critical need, we collected BALF samples from critically ill and ICU patients for metatranscriptomic sequencing analysis. Based on the metatranscriptomic microbial detection results, patients were categorized into negative, bacterial infection, viral infection, and fungal infection, and characteristic gene screening was conducted on the transcriptome data of human genes. Using the transcriptome data of these characteristic genes, classification diagnostic sub-models were constructed employing various machine learning algorithms. However, a solitary machine learning model may encounter limitations stemming from data quality, risks of overfitting, and deficiencies in model generalization within the biological context. In contrast, ensemble learning amalgamates the strengths of diverse models, thereby reducing model bias and overfitting risk, ensuring generalizability across subsets, laying the foundation for robust ensemble learning and enhancing the robustness of feature interpretation. Therefore, stacking-based ensemble learning models for each sub-model were developed using Lasso, ultimately yielding a rapid, cost-effective classification diagnostic method that only necessitates the detection of a few characteristic genes. Test results indicated that the developed method exhibited high consistency in diagnostic accuracy with metatranscriptomic sequencing in distinguishing whether patients were infected and the type of infection (viral and bacterial), thus serving as a potential auxiliary diagnostic method for pulmonary infections of unknown etiology in patients with severe illness, critical condition, and those admitted to the ICU.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study analyzed BALF specimens collected from 180 critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) between 2021 and 2023 from Zhengzhou Kingmed Diagnostics. Patients with respiratory system infections of unknown etiology were included, while those under 18 years of age were excluded. All specimens underwent metatranscriptomic sequencing. Based on metatranscriptomic data analysis (Supplementary Table S1), data from non-infected patients (n = 41) and infected patients (n = 139) were included in subsequent analyses. Infected patients were further stratified into three diagnostic groups: bacterial infection (n = 91), viral infection (n = 33), and fungal infection (n = 15). The pathogenic microbial infection model incorporated 41 non-infected cases alongside 139 confirmed infected cases. For pathogenic bacterial infection classification, the cohort comprised 91 bacterial infected patients compared with 89 non-bacterial patients. Similarly, the pathogenic viral infection model analyzed 33 viral infected cases against 147 non-viral infected cases. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Kingmed Diagnostics (No.2023160), and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the ethics committee of Kingmed Diagnostics waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Metatranscriptomic sequencing

The Metatranscriptomic sequencing was carried out by KingMed Diagnostics. General DNA/RNA extraction kit (TR202-50) from GENSTONE Biotech was employed to extract total RNA from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Pathogenic microbial RNA detection kits (KS619-RNAmN48) from KingCreate Biotechnology were used to construct sequencing libraries, with library lengths ranging from 250 to 400 base pairs. Sequencing was performed using the Illumina NextSeq 550 platform. Each sample yielded over 2 Gb of raw data.

Bioinformatics analysis and statistical tests

Metatranscriptomic data of microbiota processing: After undergoing quality control with the fastp software13 the raw data underwent filtering to remove low-quality and low-complexity reads. Subsequently, adapter sequences and duplicate reads were eliminated, followed by sequence alignment. Reads aligned to microorganisms were then quantified. The proprietary database developed by KingMed Diagnostics comprised over 11,000 bacterial species, 7,300 viral species, and 1,600 fungal species.

Metatranscriptomic data of human processing: FastQC14 was employed to assess the quality of raw sequencing reads, followed by alignment using Hisat2 software15,16 and deduplication and sorting using Samtools software17. Subsequently, featureCounts software18 was utilized to obtain count data and calculate Transcripts Per Million (TPM). Utilizing the cmdscale function and Vegan package19 both t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (tSNE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) were conducted on TPM data derived from two sample groups. Differential analysis on count data from the same two sample groups was carried out using DESeq220, EdgeR21and Limma packages22. Simultaneously, statistical analysis on Transcripts Per Million (TPM) data from the two groups was performed using Wilcoxon tests. Hyperparamter details were set as follows: DESeq2: fitType = “mean”, minReplicatesForReplace = 7, parallel = FALSE. Genes with padj < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1 were considered significant; limma: The design matrix was constructed using model.matrix(~ GroupLabel), and empirical Bayes moderation was applied via eBayes(). Significance thresholds: P.Value < 0.05, |logFC| > 1; Wilcoxon test: Non-parametric rank-sum test applied on a per-gene basis, using default settings. Genes with p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1 were retained; edgeR: Normalization with calcNormFactors(), dispersion estimated using estimateDisp(), followed by glmFit() and glmLRT() for model fitting and hypothesis testing. Design matrix: model.matrix(~ GroupLabel). Genes with P.Value < 0.05 and |logFC| > 1 were selected. Subsequently, intersecting genes identified from the four differential analysis methods were selected to determine differentially expressed genes, and the ggpubr package23 was employed to generate a Venn diagram. Heatmaps were generated using the pheatmap package24. Additionally, the clusterProfiler package25 was utilized for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)26,27,28 pathway analysis, while the IOBR package29 was employed for immune infiltration analysis.

Machine learning model construction

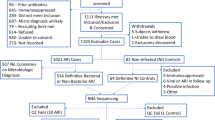

This study included a total of 180 samples for a binary classification task (infection vs. non-infection, bacterial infection vs. non-bacterial infection or viral infection vs. non- viral infection). The samples were randomly divided into training set and testing set at a 7:3 ratio, resulting in 126 samples used for training and 54 for testing. Differential genes were analyzed using the training set and further screened using three machine learning algorithms: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (Lasso). The intersection genes, representing the input features for the model, were obtained through analysis using the ggpubr package. Subsequently, thirteen algorithms, including Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Naive Bayes, Neural Network, RF, Elastic Net, Ridge Regression, Decision Tree, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Linear Model (LM), SVM, RPart, Generalized Linear Models (GLM), and Lasso, were employed to construct diagnostic sub-models. The performance of each model was assessed, and finally, the efficiency of each sub-model was integrated using the Lasso algorithm to build a classification diagnostic model based on ensemble learning. The hyperparamter details of each model were shown in Supplementary Table S2. The effectiveness of the model was evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation on the training set samples, visualized via pROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) package30 and further tested on the test set samples to assess its performance (Fig. 1). The key components of the entire modeling pipeline are as follows:

The workflow of this study. This study presents a comprehensive procedure for analyzing host transcriptional profiles in severe respiratory infections. BALF specimens from 180 critically ill patients were subjected to metatranscriptomic analysis. Samples were categorized into four groups based on microbiological findings: microbial infection, bacterial infection, viral infection, and non-infected. Each group was randomly divided into training and testing sets at a 7:3 ratio. Due to limited fungal samples and substantial interindividual variability, fungal specimens were excluded from subsequent analysis. Differential analysis of host transcriptomes identified differentially expressed genes. SVM, RF, and Lasso methods were utilized for host biomarker selection. Integration learning was employed to construct a final diagnostic model by combining 13 machine learning sub-models. The effectiveness and validation of the model were assessed using five-fold cross-validation on the training set and validation on the testing set.

-

1.

Dependent Variable (Target): The outcome variable (AllLable) is a binary classification label indicating clinical infection status: - Class 0: non-infected, - Class 1: infected. We constructed four types of datasets: negative, bacteria, virus, and fungus. This binary variable serves as the target (y) for all supervised classification models.

-

2.

Predictor Variables (Features): Input features are selected from differentially expressed genes (DEGs), identified through statistical comparisons (DESeq2, limma, Wilcoxon). Prior to modeling, genes with low variance were removed. Features were ranked using standard deviation, and selected genes were assembled into the predictor matrix: x_train <- as. matrix (gene_expression [, colnames(gene_expression) %in% ModelGene$ENSG]).

-

3.

Feature Selection and Cross-Validation: Each model incorporates feature selection and validation were showed in Supplementary Table S3.

-

4.

Classification Task Type: All models were built for binary classification, aiming to distinguish between infected and non-infected samples using gene expression data.

-

5.

Evaluation Metrics: To assess model performance and robustness, we applied Accuracy (Proportion of correctly predicted samples), AUC (Reflects model discrimination ability), Mean Predicted Probability (Average model confidence for each sample), Cross-validation average score (Stability across folds), four assessment criteria.

Results

Model construction for pathogenic microbial infection

To develop a diagnostic model for pathogenic microbial infections, we first established comparative cohorts based on metagenomic sequencing results. There were no significant differences in gender and age between the pathogenic microbial infected and non-infected cohorts (Fig. 2A). tSNE analysis revealed significant differentiation between the two groups of samples (p = 0.002), and consistent results were obtained through PCA analysis (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B and Figure S1A). Immune cell composition analysis in the BALF showed a significant increase in immune cells promoting the immune response, including B cells, eosinophils, CD4 + T cells, CD8 + T cells, Th2 cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, in the cohort with pathogenic microbial infections compared to those without, whereas the population of M2-type macrophages suppressing the immune response was significantly reduced. This suggested a heightened immune response in patients with detected pathogenic microbes compared to those without (Fig. 2C).

Model construction for pathogenic microbial infections. (A) Analysis of age and gender disparities in patients with detected and undetected pathogenic microorganisms. (B) tSNE of host genes in the metatranscriptomic data of patients with detected (n = 139) and undetected (n = 41) pathogenic microorganisms. (C) Analysis of immune cell composition in BALF from two groups of patients using the deconvolution algorithm. (D) Venn diagram analysis of differential genes commonly identified by four differential gene algorithms, Wilcoxon screening threshold as adjust-p < 0.05. (E) GO enrichment analysis of differential genes, all the terms’ pvalue < 0.05. (F) KEGG enrichment analysis of differential genes, all the pathways’ pvalue < 0.05. (G) Input genes for feature selection by SVM, RF, and Lasso models. (H-I) Coefficient path of integrated model based on Lasso (H) and 10-fold cross-validation regularization path (I). (J) The coefficients of each sub-model in the Lasso linear regression integrated model. (K) Five-fold cross-validation of training set samples for model evaluation and (L) testing set samples for model test.

To identify DEGs between the two cohorts, we employed three algorithms (Figure S1B-D). Furthermore, we performed DEG analysis using Wilcoxon test. By intersecting the results from these four methods, we identified a set of DEGs between the two cohorts, with 132 genes downregulation, compared to the pathogenic microbial non- infection cohort (Fig. 2D and Figure S1E). GO enrichment analysis indicated that these DEGs are associated with cellular translation, oxidative phosphorylation, cellular respiration, electron transport chain, respiratory complexes, cytochrome c oxidase activity, as well as cell adhesion and migration (Fig. 2E). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the differential genes mainly affect ribosome biogenesis, mitochondrial energy metabolism and quality control, and intracellular oxidative stress (Fig. 2F). The combined results of GO and KEGG enrichment analyses suggested that these DEGs mainly impact cellular energy metabolism and substance metabolism, which are significantly affected following pathogenic microbial infections.

Subsequently, we conducted screening of DEGs related to the presence or absence of pathogenic microbial infections. SVM algorithm identified 66 genes, RF algorithm identified 66 genes, and Lasso algorithm identified 9 genes. By taking the intersection of these three sets of genes, FIS1, MARCKSL1, RPL8, RPS15, RPS5, and STUB1 were selected as input genes for the sub-model (Fig. 2G). We then constructed thirteen classification sub-models using thirteen algorithms, and the prediction outputs of each sample in the test set across all 13 models are presented in Supplementary Table S4. The SHAP values of each input gene were shown in Figure S1F. Subsequently, we integrated these sub-models using Lasso algorithm and selected the best regularization parameter (Lambda) through coefficient calculation (Fig. 2H) and 10-fold cross-validation (Fig. 2I), obtaining the optimal Lambda value of 3.3e-03. The determined lambda value was subsequently employed to construct a classification model, formally expressed as: S = −0.13 + 0.14EMLP + 0.04 ENaiveBayes + 0.11 ENeuralNet + 0.49 ERF + 0.48 EGBM (Fig. 2J). Five-fold cross-validation results on the training set demonstrated the model’s robust diagnostic performance, with an AUC value of 0.984 (Fig. 2K). Furthermore, test using the test set yielded an AUC value of 0.865 (Fig. 2L), indicating good consistency of the metatranscriptomic detection of pathogenic microbial infections.

Model construction for pathogenic bacterial infection

In this part of the research, we aimed to establish a diagnostic model that aligned with the results of metatranscriptomic detection of solely bacterial infection. Cases without bacterial infection and with bacterial infection were identified (Fig. 3A). A substantial disparity emerged between the cohorts, as evidenced by tSNE (p < 0.001) and PCA(p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B and Figure S2A). DEGs were discerned using the same method as described above, with 1719 genes downregulation and 44 genes upregulation compared to cases without infection (Fig. 3C and S2B-E). GO enrichment analysis unveiled associations with bacterial infection, such as regulation of innate immune response, response to lipopolysaccharide, response to molecule of bacterial origin, focal adhesion, MHC protein complex binding (Fig. 3D). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed differential gene impacted on TNF signaling, NF-kappa B signaling, Tight junction, Necroptosis, MAPK signaling and bacterial invasion of epithelial cells, which were all associated with bacterial infection (Fig. 3E). Besides, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) enrichment analysis also identified numerous pathways associated with bacterial infection, for instance antigen processing and presentation, natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity, lysosome, apoptosis, endocytosis and MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 3F). These results suggested that the screened DEGs were highly correlated with bacterial infection.

Model construction for pathogenic bacterial infections. (A) Examination of demographic variations in individuals infected with Bacteria (n = 91) and without pathogenic microorganisms (n = 89). (B) Utilization of tSNE to analyze the genetic makeup of hosts in metatranscriptomic datasets of patients harboring bacterial infection and non-bacterial infection. (C) Investigation into the overlap of significant gene differences derived from four distinct algorithms using Venn diagrams, employing a Wilcoxon threshold with adjust-p < 0.05. (D) GO enrichment analyses on disparate gene sets, with significance established at a p-value threshold of < 0.05 for all terms. (E) Assessment of KEGG enrichment on differential gene sets, setting a significance threshold of < 0.05 for all pathways. (F) GSEA enrichment analysis, setting a significance threshold of < 0.05 for all pathways. (G) Selection of feature genes for predictive modeling through SVM, RF, and Lasso methodologies, the Mann-Whitney U was used to define significant differences, ***p < 0.001. (H-I) Visualization of coefficient paths within an integrated model based on Lasso regularization (H) and elucidation of regularization paths via 10-fold cross-validation (I). (J) Determination of individual coefficients within the integrated Lasso linear regression model. (K) Application of five-fold cross-validation to assess model performance on training set samples and (L) Test model efficacy on independent testing set samples.

DEGs underwent further screening, resulting in 10 genes identified by SVM, 10 genes selected by RF, and 17 genes determined by Lasso. By identifying the intersecting genes, AKT1, CRIP1, GTF3A, HDGF, HLA-DPB1, OGFR, PEBP1 and RPL13 genes were obtained and as input genes for next model constructions (Fig. 3G). The 13 classification sub-models were constructed, and the prediction outputs of each sample in the test set across all 13 models are presented in Supplementary Table S4. The SHAP value of each input gene were shown in Figure S2F. The 13 sub-models were integrated via the Lasso algorithm, coupled with selection of the optimal regularization parameter (Lambda) through coefficient calculation (Fig. 3H) and 10-fold cross-validation (Fig. 3I), yielded an optimal Lambda value of 5.63e-04. Leveraging this Lambda value, an integrated learning model was constructed, as represented by: S = −0.05 + 0.06EMLP + 0.25 ENeuralNet + 0.47 ERF + 0.33 EGBM (Fig. 3J). Five-fold cross-validation results on the training set underscored the model’s robust diagnostic prowess, with an AUC value of 0.98 (Fig. 3K). Furthermore, test utilizing the test set yielded an AUC value of 0.871 (Fig. 3L), indicating substantial concordance with the metatranscriptomic detection of pathogenic bacteria infections.

Model construction for pathogenic viral infection

Following our investigation, we endeavored to formulate a diagnostic framework congruent with findings from metatranscriptomic assessments exclusive to viral infections. Among our cohort, delineation revealed 147 cases devoid of viral infection and 33 cases characterized by viral infection (Fig. 4A). A conspicuous dichotomy surfaced between these cohorts, as substantiated by tSNE (p < 0.001) and PCA (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B and Figure S3A). Employing analogous methodologies as aforementioned, we identified 598 genes exhibiting downregulation and 2 genes displaying upregulation in comparison to non-viral infection cases (Fig. 4C and Figure S3B-E). GO enrichment analysis illuminated associations indicative of viral infection, encompassing the viral process, antigen processing and presentation, MHC protein complex assembly, aerobic respiration, immune receptor activity and peptide antigen binding (Fig. 4D). Moreover, KEGG enrichment analysis unveiled perturbed genes implicated in TH17 cell differentiation, Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation, Oxidative Phosphorylation, influenza A, COVID-19, Necroptosis, lysosome, antigen processing and presentation (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, GSEA identified numerous pathways linked to mitochondrial function, including Huntington disease, Parkinson disease and Oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 4F). These findings collectively indicated a correlation between the identified DEGs and viral infection.

Model construction for pathogenic viral infections. (A) Exploration of demographic disparities between individuals infected with Viral infection (n = 33) and those lacking pathogenic microorganism infection (n = 147). (B) Utilization of tSNE to analyze the genetic composition of hosts in metatranscriptomic datasets from patients with viral infection and non-viral infection. (C) Investigation into overlapping gene disparities using Venn diagrams derived from four distinct algorithms, employing a Wilcoxon threshold with adjust-p < 0.05. (D) Conducting GO enrichment analyses on diverse gene sets, with significance determined at a p-value threshold of < 0.05 for all terms. (E) Assessment of KEGG enrichment on differential gene sets, setting a significance threshold of < 0.05 for all pathways. (F) Analysis using GSEA, with a significance threshold of < 0.05 for all pathways. (G) Selection of feature genes for predictive model via SVM, RF, and Lasso methodologies, with significant differences defined using Mann-Whitney U test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (H-I) Representation of coefficient paths within an integrated model utilizing Lasso regularization (H) and elucidation of regularization paths via 10-fold cross-validation (I). (J) Determination of individual coefficients within the integrated Lasso linear regression model. (K-L) Application of five-fold cross-validation to assess model performance on training set samples (K) and test model efficacy on independent testing set samples (L).

Subsequently, DEGs underwent further screening, yielding CPVL, DENND4C, MAFB, PTGER4, SLAMF8, TSPO and UBE2Q2 genes, which served as input features for subsequent model construction (Fig. 4G). Thirteen classification sub-models were assembled and the prediction outputs of each sample in the test set across all 13 models are presented in Supplementary Table S4. The SHAP value of each input gene were shown in Figure S3F. The sub-models were integrated through the Lasso algorithm, incorporating the optimal regularization parameter (Lambda) determined via coefficient calculation (Fig. 4H) and 10-fold cross-validation (Fig. 4I), resulting in an optimal Lambda value of 1.29e-03. Leveraging this Lambda value, a composite classification model was devised, represented by the equation: S = −0.20 + 0.28EMLP + 0.15 ENeuralNet + 0.91 ERF + 0.05 EGBM + 0.10 EElastic − 0.05 ENaiveBayes (Fig. 4J). Five-fold cross-validation on the training set underscored the robust diagnostic efficacy of the model, yielding an AUC value of 0.98 (Fig. 4K). Furthermore, test using an independent test dataset yielded an AUC value of 0.934 (Fig. 4L), indicating significant concordance with metatranscriptomic detection of pathogenic viral infections.

Robustness assessment of three stacking-based models

To further evaluate the robustness, we designed a comprehensive evaluation framework to quantitatively compare the performance stability of the three-stacking model against 13 conventional classifiers using the test cohorts. Specifically, we introduced a 5-dimensional evaluation scheme capturing both accuracy and generalization performance across heterogeneous subsets: AUC (measures overall discrimination ability); Accuracy (measures performance at a fixed threshold); Subset Accuracy Std (reflects prediction stability across different subgroups); Subset AUC Std (captures discrimination consistency across subsets); Subset Top3 Score (quantifies how often the model ranks in the top three across key subsets). All test set samples were used to evaluate the three stacking models and their 13 constituent sub-models, and average of the five metrics were calculated (Supplementary Table S5). We further formulated the following scoring function to aggregate these metrics into a single robustness score: 0.2 × AUCaverage + 0.2 × Accuracyaverage + 0.2 × (1 − Subset Accuracy Std) average + 0.2 × (1 − AUC Std across Subsets) average + 0.2 × Subset Top3 Score (Normalized)average. This balanced scoring system prioritizes both global predictive quality and cross-scenario stability, with a modest boost from localized subset performance. The results showed that stacking models achieved the highest robustness score 0.93, outperforming all single model. This was further illustrated with visualizations including radar plots (Fig. 5A) and score distribution (Fig. 5B), highlighting its superior stability and resilience in diverse clinical conditions. In summary, we quantitatively and visually demonstrated that the stacking model was not only accurate but also robust across multiple data partitions, substantiating its advantage over individual models.

Robustness assessment of three stacking-based models. (A) Radar plot visualization of the average scores across five evaluation metrics for the three stacking models and each individual sub-model on all test set samples. (B) Robustness scoring comparison between the stacking models and 13 single machine learning models.

Discussion

Particularly concerning are patients in critical conditions, including those in ICU, where delayed diagnosis of severe pulmonary infections can lead to organ dysfunction and increased mortality risk31. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antiviral agents, and antifungal medications are frequently employed as empiric therapies. However, up to half of ICU patients receiving empirical antimicrobial therapy lack definitive confirmation of infection. Administration of antimicrobial agents to non-infected patients not only fails to confer benefits but may also introduce potential risks of adverse events, secondary opportunistic pathogen infections, and drug resistance. Traditional microbiological detection methods, primarily microbial culture, suffer from limitations such as stringent technical requirements and conditions, resulting in unstable culture outcomes and poor timeliness, which may impede disease progression monitoring in critically ill patients awaiting results. The advent of sequencing technologies has introduced metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses, enabling discrimination between infection and non-infection states and accurate identification of microbial taxa. However, the technical complexity of these assays, combined with prolonged turnaround times for data analysis and result interpretation (typically 2–7 days in clinical settings), often compromises timely clinical decision-making. In China’s diagnostic landscape, the substantial cost (approximately 3,000 RMB per sample) and time requirements for BALF metatranscriptomic sequencing further limit its routine clinical application for critically ill, severely ill, and ICU patients. On the other hand, compared to metagenomic analyses, metatranscriptomic sequencing can identify the impact of infecting microorganisms on host gene expression32facilitating the identification of host gene biomarkers for infection diagnosis33. However, effective host biomarkers have yet to be fully elucidated, and diagnostic models based on basic biomarkers require further development.

In this study, we proposed a targeted framework that simultaneously addresses. Retrospective samples of BALF from respiratory and critically ill patients were collected, followed by metatranscriptomic sequencing. Based on metatranscriptomic microbial detection results, patients were categorized into 41 negative cases, 33 bacterial infections, 91 viral infections, and 15 fungal infections. Due to the limited number of fungal infection cases and substantial inter-individual variations (p = 0.475) (Figure S4A-B), further analysis was not pursued, constituting a major limitation of this study. However, further investigation will be conducted as more samples of fungal infections are continuously collected. Transcriptomic data of host genes were selected as characteristic genes from patients’ data with microbial detection results indicating bacterial or viral infections and those without detection. Using these characteristic gene transcriptomic data, various machine learning algorithms were employed to construct classification diagnostic sub-models. Subsequently, a stacking-based ensemble learning model was constructed using Lasso to integrate the sub-models, ultimately forming a rapid and inexpensive classification diagnostic method requiring the detection of only a few host gene biomarkers. Compared to utilizing a single model, ensemble learning models allowed for the consideration of the efficacy of multiple models in result evaluation, thereby enhancing predictive performance, mitigating the risk of overfitting, bolstering robustness, and providing increased flexibility and interpretability34,35. We emphasized that the choice to apply a unified set of 13 models across all datasets was not arbitrary, but rather driven by a need to maintain methodological consistency and ensure fair cross-cohort evaluation. The final stacking model was thus selected based on its superior performance and robustness across all datasets, balancing predictive power with technical uniformity. The average performance of the five-fold cross-validation models for distinguishing infection from non-infection was AUC = 0.984, for distinguishing bacterial infection from non-bacterial infection was AUC = 0.98, and for distinguishing viral infection from non- viral infection was AUC = 0.98. Moreover, test set results demonstrated that the developed method exhibited high consistency in diagnostic performance compared to metatranscriptomic sequencing in differentiating patients with infection (AUC = 0.865) and infection types (viral AUC = 0.934 and bacterial AUC = 0.871), serving as a potential adjunctive diagnostic method for unidentified pulmonary infections in critically ill, severely ill, and ICU patients.

Our study presents a prospective adjunctive diagnostic approach based on qPCR detection of 21 genes, which requires only approximately 210 RMB (∼93% reduction compared to conventional metatranscriptomic sequencing) with a turnaround time of less than 6 h while maintaining diagnostic accuracy comparable to metatranscriptomic sequencing, enabling the identification of infection status and type in pulmonary infections of undetermined etiology among critically ill, severely ill, and ICU patients. Our developed detection method holds promise for reducing medical costs, mitigating drug selection pressures and adverse effects, and improving patient outcomes. Future directions of this study could involve integrated analysis linking pathogen metagenomic features with host immune signatures. A multi-omics data fusion approach would help elucidate critical molecular patterns of pathogen-host interactions, ultimately enhancing clinical diagnostic performance.

Data availability

The metatranscriptomic raw data generated and analyzed in this project are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

References

Kradin, R. L. & Mark, E. J. 8 - Pathology of Pulmonary Infection (Elsevier, 2018).

Whiteside, S. A., McGinniss, J. E. & Collman, R. G. The lung microbiome: progress and promise. J. Clin. Invest. 131 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI150473 (2021).

Timsit, J. F. et al. Rationalizing antimicrobial therapy in the ICU: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 45, 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05520-5 (2019).

Jain, S. et al. Community-Acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl. J. Med. 373, 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1500245 (2015).

Versporten, A. et al. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob Health. 6, e619–e629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30186-4 (2018).

Guo, Y. et al. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing to identify pathogens and cancer in lung biopsy tissue. EBioMedicine 73, 103639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103639 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Clinical application and evaluation of metagenomic Next-Generation sequencing in pulmonary infection with pleural effusion. Infect. Drug Resist. 15, 2813–2824. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S365757 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Metagenomic Next-Generation sequencing versus traditional pathogen detection in the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary infectious lesions. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S235182 (2020).

Charalampous, T. et al. Nanopore metagenomics enables rapid clinical diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory infection. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0156-5 (2019).

Zhu, N. et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in china, 2019. N Engl. J. Med. 382, 727–733. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 (2020).

Carr, V. R. & Chaguza, C. Metagenomics for surveillance of respiratory pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 285. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00541-8 (2021).

Diao, Z., Han, D., Zhang, R. & Li, J. Metagenomics next-generation sequencing tests take the stage in the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infections. J. Adv. Res. 38, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2021.09.012 (2022).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Andrews, S. (Cambridge, United Kingdom, (2010).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 12, 357–360. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 (2014).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. EdgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 (2010).

Smyth, G. (New York: Springer, (2005).

Hornik, K. The comprehensive R archive network. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Stat. 4, 394–398 (2012).

Kolde, R. Pheatmap: pretty heatmaps. R Package Version. 1, 726 (2019).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics: J. Integr. Biology. 16, 284–287 (2012).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2024).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. K. E. G. G. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Zeng, D. et al. Multi-Omics Immuno-Oncology biological research to Decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 12, 687975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.687975 (2021).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 1–8 (2011).

Detsis, M., Karanika, S., Mylonakis, E. I. C. U. & Acquisition Rate Risk factors, and clinical significance of digestive tract colonization with Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing enterobacteriaceae: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 45, 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002253 (2017).

Ramachandran, P. S. et al. Integrating central nervous system metagenomics and host response for diagnosis of tuberculosis meningitis and its mimics. Nat. Commun. 13, 1675. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29353-x (2022).

Fan, S. et al. Integrating host transcriptomic signatures for distinguishing autoimmune encephalitis in cerebrospinal fluid by metagenomic sequencing. Cell. Biosci. 13, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-023-01047-x (2023).

Polikar, R. Ensemble based systems in decision making. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 6, 21–45 (2006).

Kuncheva, L. I. & Rodríguez, J. J. A weighted voting framework for classifiers ensembles. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 38, 259–275 (2014).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of Young Scientists of China (32200438).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J.-L. and W.F.-L. designed and performed the project, wrote and revised the manuscript, supervised the project. T.-Z. and Y.-D. designed this project, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. W.T.-W. and Z.-Z. collected and interpretated the samples and analyzed the data. H.Q.-W. revised the manuscript and supervised the project. Y.L.-W. and S.T.-X. assisted in revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Kingmed Diagnostics (2023160), and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the ethics committee of Kingmed Diagnostics waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Code availability

Code supporting the study are available in https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15655782.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Deng, Y., Wang, W. et al. Stacking ensemble learning models diagnose pulmonary infections using host transcriptome data from metatranscriptomics. Sci Rep 15, 30516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15914-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15914-9