Abstract

Blended learning has been widely used and popularized in recent years. It was originally designed to create a highly engaging learning experience for students; however, in practice, it often falls short. In particular, online learning within blended learning environments suffers from a lack or inadequacy of online presence, which is likely to trigger students’ negative academic emotions during online learning, leading to poor learning outcomes. However, the impact of online academic emotions on learning performance in blended learning has received little attention in empirical studies. This study examines the relationships among online academic emotions, online presence, and learning performance in blended learning. A stratified sampling questionnaire was used to survey 1,192 college and university students, and 971 valid questionnaires were returned. Through descriptive and correlational analyses of each research variable, the predictive relationships among the variables and the mediating effect of online academic emotions in the process of influencing online presence on blended learning performance were explored. The findings indicate that online presence significantly positively predicts positive online academic emotions and significantly negatively predicts negative online academic emotions in a blended learning environment. Online presence has a positive predictive effect on learning performance, and positive-low arousal academic emotions (calmness and relaxation) partially mediate the relationship between online presence and learning performance. This study may encourage instructors to emphasize the impact of online academic emotions on learning performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid development of information technology and the continuous improvement and popularization of mobile devices have created excellent conditions for the development of blended learning. Blended learning is a teaching method widely used in the field of higher education that integrates the traditional teaching mode and modern information technology. The Horizon Report 2022 (Teaching and Learning Edition) by the American Association for Information Technology in Higher Education focuses on new trends in the development of global higher education in the era of digital intelligence convergence, highlighting the mainstreaming of blended learning. Blended learning was originally conceived to enhance student engagement through the strategic integration of online and face-to-face modalities. However, meta-analytic evidence reveals that these anticipated benefits have not been consistently realized in practice10, demonstrating a persistent divergence between theoretical expectations and empirical outcomes. The vast majority of instructors have not significantly changed the content or methods of traditional face-to-face teaching, and blended learning continues to face many problems and challenges42,46. The successful implementation of blended learning depends on specific enabling conditions, particularly deliberate pedagogical design, yet many current implementations lack the strategic planning required to effectively integrate both modalities. This implementation gap highlights unresolved challenges in adapting instructional approaches to blended learning environments, ultimately limiting its educational potential without effective instructional design.

Additionally, blended learning suffers from a lack of positive learning attitudes, low engagement9,19,54, low learning efficiency20, insufficient motivation, poor learning quality50, insufficient learning competence6, and insufficient mastery of learning strategies18, among other problems. In conclusion, these issues indicate that online learning within blended learning environments suffers from a lack of or insufficient online presence. These problems are likely to trigger negative academic emotions in students engaged in online learning, leading to poor learning performance. Although previous studies have focused on the impact of components of online presence on learning performance within the Community of Inquiry framework from various perspectives, few studies have specifically investigated how online presence influences emotional experiences in blended learning environments. This study addresses this critical gap through a theoretical model that resolves negative academic emotions arising from insufficient online presence in blended education. The model establishes a theoretical foundation for designing instructional practices that enhance learning performance by regulating online academic emotions.

Literature review

The predictive role of online presence in online academic emotions in blended learning

Online presence is derived from the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework, which reflects a collaborative constructivist approach to learning and a collaborative environment based on open and purposeful communication. As meaningful educational experiences are viewed as embedded in a Community of Inquiry composed of teachers and students, this structural framework emphasizes the important role of the environment in shaping the learning experience. The Community of Inquiry framework consists of three basic elements: social presence (SP), cognitive presence (CP), and teaching presence (TP). These three types of presence overlap, interact with, and reinforce each other to enable the formation of meaningful learning experiences for learners in the blended learning process22.

The concept of academic emotions was first articulated by Pekrun et al.38, who defined “academic emotions” as emotions that are directly related to classroom instruction, coursework, and academic performance. Academic emotions can be systematically categorized into four distinct dimensions based on valence (positive/negative) and arousal (high/low). Positive-high arousal academic emotions (e.g., enjoyment, excitement) refer to pleasant affective states accompanied by elevated psychological activation levels that typically enhance motivation and cognitive engagement. Positive-low arousal academic emotions (e.g., relaxation, calmness, contentment) represent pleasant affective states characterized by reduced psychological activation, often associated with sustained focus and tranquil task engagement. Negative-high arousal academic emotions (e.g., anxiety, frustration) constitute unpleasant affective states with heightened psychological activation, commonly associated with perceived urgency, stress, or acute discomfort. Negative-low arousal academic emotions (e.g., exhaustion, boredom, hopelessness) reflect unpleasant affective states exhibiting diminished psychological activation, frequently manifesting as reduced behavioral initiative or withdrawal tendencies.

Research on teaching presence and academic emotions has reported that teacher support not only directly affects learners’ learning outcomes but also influences their emotions. For example, teacher support is significantly positively correlated with positive academic emotions and negatively correlated with negative academic emotions44. Instructional design influences learners’ cognitive processing and learning outcomes by inducing emotional factors37.

In research on social presence and academic emotions, Mu et al.36 reported that student-to-student interactions allow students to feel the presence of their peers and teachers, mitigating the loneliness of online learning. With respect to their cognitive presence and academic emotions, students construct knowledge by stimulating, discussing, and actively seeking innovation with their peers under the guidance of teachers. It can be inferred that teacher guidance and how peer discussions are conducted can affect academic emotions. However, previous studies have only addressed either offline or fully online learning environments, and few have focused on online academic emotions in blended learning.

Online presence and learning performance

A review of the literature indicates that online learning within blended learning environments suffers from missing or insufficient online presence9,19,20,50,54. These issues are likely to trigger negative academic emotions in online learners, which may lead to unsatisfactory learning outcomes. Learning performance is a measure of learners’ learning outcomes and is one of the main criteria for assessing the quality of teaching and learning, which is essential across all disciplines during teaching and learning activities. In 2004, the American Educational Communication and Technology Association (AECT) defined educational technology, emphasizing that learning performance refers to the ability of learners to apply newly acquired knowledge and skills. It refers not only to the acquisition of basic knowledge and skills but also to the ability to flexibly apply the knowledge and skills learned. In this study, learning performance was considered the result of students’ performance in cognitive, affective, skill, and behavioural aspects after a certain kind of learning51 and was measured using four indicators: communicative ability, self-regulated learning ability, learning perseverance, and innovative thinking ability.

Teaching presence refers to students’ interactions with instructional tools and learning activities. Interactive instructional design, appropriate pedagogical methods, visual layouts of instructional courseware, and flexible course structures not only increase the effectiveness of online learning but also promote students’ reflection on learning and deep learning16. Online teaching can be tailored to specific content and can use digital technology to design and organize better learning experiences than offline teaching41. Social presence is important in learning activities where students not only acquire new knowledge but also construct knowledge with their peers39, and students with greater social presence show better academic performance with these activities15. Curriculum design plays an important role in students’ social presence by increasing meaningful interactions among students, which can positively affect their academic performance27.

The development of online learning environments requires understanding how to facilitate the collaborative knowledge-building process and create learning environments that support meaningful student engagement and interaction. Asynchronous online discussions are designed to support knowledge construction and higher-level thinking because of their predictive role in learning performance. Cognitive presence, as categorized by the Community of Inquiry framework, consists of exploration, integration, and resolution. High-achieving learners are more likely to engage in discussion tasks related to exploration, integration, and resolution34. Other studies have examined how student behaviour in asynchronous online discussions (AOD) affects academic performance, showing that certain levels of cognitive presence are associated with students’ academic performance and that students’ levels of exploration and integration predict their final academic performance21. However, previous studies have focused only on the impact of online presence on learning outcomes in fully online learning environments, with little research on the relationship between online presence and learning outcomes in blended learning.

Academic emotions and learning performance

Pekrun et al.38 proposed a “cognitive‒motivational” model of the relationship between academic emotions and learning performance, which posits that academic emotions and learning performance interact such that academic emotions can affect learning performance in various direct and indirect ways that are sometimes simple and sometimes complex. Positive academic emotions have a crucial impact on students’ academic performance17. Neuroscience research has shown that positive emotions can have beneficial effects on cognitive functioning by encouraging individuals to overcome the limits of thinking and increase cognitive flexibility. When people feel happy and comfortable, their brains become more flexible and creative when dealing with problems33. High task valence, high success expectancy, and positive pretask emotions increase the level of effort during a task, which in turn promotes better task performance. In addition, high success expectancy predicts more positive emotions during the task. In contrast, more negative emotions predict poorer task performance28. Negative academic emotions (anger, anxiety, shame, boredom, and helplessness) negatively correlate with academic performance, and anxiety and helplessness fully mediate the relationship between critical thinking and academic performance48.

During online learning activities, students may develop positive or negative emotions that can affect the continuing process and effectiveness of their learning or online interactions60. Positive academic emotions can predict academic achievement and strengthen the positive relationships among motivation, cognitive resources, and academic achievement49. Online learning motivation positively influences online learning performance and positive academic emotions, and positive academic emotions are positively related to online learning performance62. Happiness and anxiety in online learning can promote self-directed learning57.

If teachers are unprepared for online teaching, such as failing to effectively use online teaching technology to present content clearly, design engaging courses and foster a positive online learning atmosphere, or communicate with students, it can trigger negative academic emotions such as boredom and learning weariness3. All of these factors can negatively affect students’ cognitive processes and learning performance, leading to reduced learning performance4.

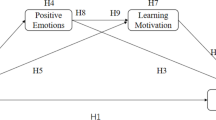

However, previous studies have focused only on the effects of academic emotions on learning performance in traditional offline or fully online learning environments, and no research has been conducted on the relationship between academic emotions and learning performance in blended learning. We propose three research questions and three hypotheses. The theoretical model hypothesized in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

H1

Online presence is a positive predictor of positive-high arousal academic emotions (H1a) and positive-low arousal academic emotions (H1b) and a negative predictor of negative-high arousal academic emotions (H1c) and negative-low arousal academic emotions (H1d).

H2

Teaching presence (H2a), social presence (H2b), and cognitive presence (H2c) significantly and positively predict learning performance.

H3

Online presence may indirectly affect learning performance through the mediation of positive-high arousal academic emotions (H3a), positive-low arousal academic emotions (H3b), negative-high arousal academic emotions (H3c), and negative-low arousal academic emotions (H3d) during online learning.

Materials and methods

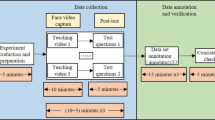

Participants and procedure

A stratified sampling method was used to administer the questionnaire survey, with stratification based on the type of school, which was divided into three levels. First, nine different categories of colleges and universities were selected in Hangzhou (1 “double first class” university, 4 provincial key universities, and 4 provincial higher vocational colleges). The proportion distribution method was then used to draw samples at each level of colleges and universities by a simple random sampling method: “double first class” university (11.3%), provincial key universities (39.5%), and provincial higher vocational colleges (49.1%). A total of 1,192 questionnaires were distributed to nine different universities in Hangzhou in several categories, and 971 valid questionnaires were returned, for an effective response rate of 81.46%. The percentages of male and female students were 55.8% and 44.2%, respectively, and the mean age was 19.17 ± 0.04 years. The respondents consisted primarily of freshmen and sophomores (92.9%), with juniors and seniors making up 7.1%. By major, 51.0% of the respondents studied humanities and social sciences, 38.1% studied science and technology, 3.9% studied agriculture and medicine, and 7.0% studied arts. By academic achievement, respondents were divided into three groups: the top third of the class (34.91%), the middle third (57.37%), and the bottom third (7.72%).

Measures

Online presence scale

This scale was adapted from Wertz’s53 Online Presence Scale, which includes three dimensions (teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence) and consists of 18 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = comparatively inconsistent, 3 = not sure, 4 = comparatively consistent, and 5 = fully consistent). The higher the score on the online presence question item is, the stronger the degree of online presence. A factorial test of all the items in the scale across the three dimensions revealed good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient of 0.980. The reliability coefficients for each dimension were as follows: teaching presence (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.962), social presence (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.957), and cognitive presence (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.959). In addition, although χ2/df = 6.643, this result was attributed to the large sample size. For the same hypothetical model, as the sample size increases, the χ2 value becomes correspondingly larger, while the value of the degrees of freedom df remains unchanged, resulting in a larger χ2/df value8,29. Therefore, in a general sense, the χ2 value or the χ2/df value alone cannot be used as a key indicator for judging the fit of the fitted model55. For the other fit indicators, the overall fit of the confirmatory factor analysis was more satisfactory, and all key indicators met the fit criteria: RMSEA = 0.076 (acceptable if < 0.08), NFI = 0.949, RFI = 0.941, IFI = 0.955, TLI = 0.948, and CFI = 0.955. The fit of this model was thus good.

Online academic emotions scale

The Online Academic Emotions Scale was adapted from the Academic Emotions Scale17, consisting of 18 items across four dimensions (positive-high arousal academic emotions, positive-low arousal academic emotions, negative-high arousal academic emotions, and negative-low arousal academic emotions) scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = comparatively inconsistent, 3 = uncertain, 4 = comparatively consistent, and 5 = fully consistent). The higher the score on the positive academic emotions item is, the greater the positive academic emotions; the higher the score on the negative academic emotions item is, the greater the negative academic emotions, and the lower the positive academic emotions. A factorial test of all the items in the scale across the four dimensions yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.789. The reliability coefficients for each dimension were as follows: positive-high arousal academic emotions (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.935), positive-low arousal academic emotions (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.914), negative-high arousal academic emotions (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.834), and negative-low arousal academic emotions (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.937). The four dimensions of online academic emotions demonstrated strong composite reliability (CR = 0.844–0.938, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.7) and satisfactory convergent validity (AVE = 0.648–0.748, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.5). Although χ2/df = 10.658, this again was due to the large sample size8,29,55, this could additionally result in an increased RMSEA. While RMSEA = 0.100, slightly exceeding the 0.08 threshold, in structural equation modelling (SEM), the evaluation of model fit requires comprehensive consideration of multiple indices, and model rationality should not be assessed based solely on any single index. The overall fit of the confirmatory factor analysis was more satisfactory based on other fit metrics, with NFI = 0.914, RFI = 0.898, IFI = 0.922, TLI = 0.907, and CFI = 0.922. Moreover, SRMR = 0.058 (below the goodness-of-fit criteria of SRMR < 0.08). The SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) was included to further validate the model’s goodness-of-fit. This robust absolute fit index quantifies the standardized discrepancy between the observed covariance matrix and model-implied covariance matrix. The model fit was acceptable.

Learning performance scale

This scale is selected from Shen’s43 Deep Learning Capability Scale, which consists of four dimensions (communication ability, self-regulated learning ability, learning persistence, and innovation thinking ability) and 16 items scored on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, and 4 = always). The higher the score on the learning performance questions is, the more effective the learning. Questions with low scale factor loadings were deleted, and the factor test showed good reliability across the four dimensions, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.977. The reliability coefficients for each dimension were as follows: communication ability (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.910), self-regulated learning ability (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.916), learning persistence (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.947), and cognitive presence (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.949). The overall fit of the confirmatory factor analysis was relatively satisfactory, with major indicators meeting the fit criteria: χ2/df = 4.492, RMSEA = 0.060 (below the goodness-of-fit criteria of RMSEA < 0.08), NFI = 0.976, RFI = 0.970, IFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.977, and CFI = 0.981, indicating a good model fit.

Statistical analyses

The statistical software used in this study were SPSS 23.0 and AMOS 24.0. First, the coefficient of internal consistency and confirmatory factor analysis were used to test the reliability, validity, and common method bias of the measurement tools, ensuring that the questionnaire method and research instruments met the required standards. The descriptive and correlational results of each research variable were then analysed to explore the predictive relationships among the research variables. To test for mediation effects, Model 4 in the SPSS micro PROCESS was used. Finally, AMOS 24.0 was used to test the model fit of the mediation model between online presence and learning performance. Structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis was conducted in AMOS using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method. ML estimation was selected for its robustness under the assumption of multivariate normality. To address potential deviations from normality and enhance robustness, bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples was applied. Bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals were generated for all path coefficients, ensuring reliable parameter estimates.

Results

Control and testing of common method bias

The data in this study were collected by the self-reports of the participants, and the relationships between the variables may have been affected by common method bias. In accordance with the recommendations of related studies, appropriate controls were applied in the measurement procedures, such as the use of anonymity during the completion of the questionnaire61. Harman’s single-factor test revealed the first factor accounted for 53.07% of the variance, exceeding the 40% threshold. To rigorously assess common method variance, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on all self-assessment items prior to data analysis. The results demonstrated poor model fit (χ2/df = 19.530, RMSEA = 0.138, NFI = 0.578, RFI = 0.570, IFI = 0.580, TLI = 0.583, and CFI = 0.599), indicating no substantial common method bias.

Descriptive and correlation results

The results of the correlation analysis revealed that the variables were significantly correlated (Table 1). Online presence was significantly and positively correlated with positive-high arousal academic emotions (p < 0.01) and positive-low arousal academic emotions (p < 0.01) and significantly and negatively correlated with negative high-arousal academic emotions (p < 0.01) and negative-low arousal academic emotions (p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d were all valid. In addition, teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence were all significantly and positively correlated (p < 0.01) with learning performance. Thus, Hypotheses H2a, H2b, and H2c were valid.

Structural model

In this study, we analysed the mediating effects of online presence, positive academic emotions, and learning performance (using AMOS 24.0), developed a model with positive-low arousal academic emotions as the mediating variable, and estimated the model using maximum likelihood estimation. The corrected model was obtained by constructing an initial model and correcting it according to a correction indicator, yielding χ2/df = 13.122, RMSEA = 0.072 < 0.08, SRMR = 0.031 < 0.08, NFI = 0.958, RFI = 0.943, IFI = 0.961, TLI = 0.947, and CFI = 0.961. In the same hypothetical model, as the sample size increases, the χ2 value increases, whereas the value of the degrees of freedom df remains unchanged, resulting in a larger χ2/df value8,29,55. However, in terms of the other fit indicators, the overall fit of the confirmatory factor analysis was relatively satisfactory, with all important indicators meeting the fit criteria. Therefore, the fit of this model was good, as shown in Fig. 2. The figure illustrates the two-dimensional structure of positive-low arousal academic emotions, comprising four items in total: two measuring calmness (Items ‘Calmness Q1’ and ‘Calmness Q2’) and two measuring relaxation (Items ‘Relaxation Q1’ and ‘Relaxation Q2’).

The mediating effect of positive-low arousal academic emotions was tested using the bootstrap method with 5,000 resamples to ensure robust confidence intervals. The results showed that the mediating effect of positive-low arousal academic emotions between online presence and learning performance in blended online learning was within the bootstrap 95% confidence interval, with the upper and lower bounds excluding 0 (0.052, 0.161); that is, the indirect effect of online presence on learning performance through positive-low arousal academic emotions was significant (supporting H3b). As shown in Table 2, online presence has a significant positive effect on positive-low arousal academic emotions (β = 0.728, p < 0.001) and learning performance (β = 0.586, p < 0.001). In addition, positive-low arousal academic emotions have a significant positive effect on learning performance (β = 0.208, p < 0.001).

In addition, the direct effect of online presence on academic performance fell within a bootstrapped 95% confidence interval that did not include 0 (0.318, 0.456); that is, the direct effect of online presence on academic effectiveness was also significant. Thus, the mediating effect was partially mediated. The indirect effect of online presence on learning performance through the positive-low arousal of academic emotions was 20.57% of the total effect, and the direct effect of online presence on learning performance was 79.43%, which was statistically significant. In summary, the main finding of this study is that positive-low arousal academic emotions partially mediate the relationship between online presence and learning performance. Thus, only H3b was supported, whereas H3a, H3c, and H3d were not validated.

Discussion

Teaching presence positively predicts learning performance

Teaching presence includes instructional design, teacher support, teacher attitudes, and online learning resources. This study shows that teaching presence in a blended learning environment can positively predict student learning performance, such that the stronger the teaching presence is, the better the learning performance. The findings of the present study are consistent with those of previous studies. First, the quality of online learning programs plays an important role in online learning performance, and the instructional design is particularly critical, as it determines whether learners are willing to choose online learning. Designing interactive teaching, selecting appropriate teaching strategies, optimizing the visual design of teaching materials, and flexibly adjusting the course structure can not only improve the effectiveness of online learning but also stimulate students’ thinking and facilitate deeper learning. The design of online learning activities affects students’ metacognitive abilities, learning attitudes, learning behaviours, and other aspects16,58.

Previous research has shown that course flexibility and quality are significantly correlated with learning satisfaction and learning transfer ability24. In addition, online learning resources, material selection, and the rationality of the arrangement all affect learning performance. Students’ online learning needs mainly include whether the course resources are sufficient, whether the course objectives are clear, whether the knowledge content is clearly explained, whether important and difficult points are emphasized and easy to understand, and whether the learning tasks in the “pre-course,” “during-course,” and “post-course” can be clearly arranged31.

Teacher support consists of teachers’ intellectual, social, emotional, and instrumental support to students26. From the perspective of social support, teacher–student interactions during the learning process has a significant effect on learner satisfaction. From the perspective of emotional support, teachers’ prompt response to students’ messages, enthusiasm, the learning atmosphere2, and the use of humorous language can predict learners’ satisfaction and reduce learning burnout59, which can contribute to learning performance. In addition, teacher‒student interaction is an important aspect of online learning that determines whether online learning occurs and the level at which it occurs14. The more online interactions students experience, the more positive their learning experiences and the better their learning outcomes will be7. The level of teacher‒student interaction can influence the effectiveness of online learning, with students who have higher levels of interaction with their teachers and peers experiencing greater learning performance45. Teacher interaction can promote greater cognitive engagement, with higher levels of interaction leading to better student learning outcomes5.

Research has shown that low-performing teachers have more difficulty managing student behaviour in cooperative learning, whereas high-performing teachers are better able to regulate student behaviour. This is due to differences in teachers’ attitudes when implementing cooperative learning; teachers’ positive attitudes before implementing cooperative learning, along with positive learning outcomes during implementation, are important factors in the success of cooperative learning in practice47. Teachers play an important role in both face-to-face and online learning, and their attitudes towards learning activities influence the effectiveness of students’ online learning. If teachers recognize the value of online learning and consider it an important method of learning, students will be more enthusiastic. In contrast, if teachers have a negative attitude towards online learning or lack enthusiasm when teaching online, it will be difficult to stimulate students’ motivation, and the learning effect will be poor24. Blended learning is an innovation in traditional teaching methods. It can be inferred that teachers’ attitudes towards blended learning affect students’ learning experiences and performance in such environments.

Social presence positively predicts learning performance

Social presence mainly includes peer support and group membership. This study shows that in a blended learning environment, social presence positively predicts students’ learning performance, and increased social presence can promote learning performance. Consistent with previous research, peer support was significantly and positively correlated with the persistence and reflectiveness of learners’ listening behaviours in asynchronous online discussions. All dimensions of online listening were significantly and positively related to online speaking, learning performance, and learning satisfaction, and online listening was a significant predictor of learning performance11. In other words, increasing peer support aids learners’ listening behaviour in asynchronous online discussions, whereas the actual effect of listening behaviour can affect their learning performance.

Previous research has shown that collaborative learning, in which students exhibit better social interaction behaviours in computer-supported collaborative learning environments, requires frequent interactions in the early stages of collaboration and that the establishment of a sense of online community and group affiliation contributes to learning performance30. In addition, based on constructivist or collaborative learning models, interactive communication and media presentation can facilitate the development of learners’ higher-order thinking skills and the construction of conceptual knowledge. Interactive discussion and brainstorming during the online learning process, as well as the management of the learning process and multimedia presentation of learning materials, can stimulate learners’ motivation to continuously participate in online learning and form an effective learning model13, thus contributing to improving blended learning performance.

Cognitive presence positively predicts learning performance

Cognitive presence refers to knowledge construction. This study shows that cognitive presence in a blended learning environment positively predicts students’ learning performance such that improving cognitive presence can promote learning performance. In support of the findings of previous research, a strong relationship was found between collaborative constructivism and higher-order learning performance. Establishing and sustaining cognitive presence and deep learning in a blended learning environment relies on a dynamic balance of teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence1. Instructional approaches that enhance cognitive presence significantly improve learner performance13. In online forums, students’ cognitive presence can be enhanced by reflecting on course materials, applying lectures to practice, and constructing knowledge, which can also improve academic performance21.

Mediating effect of online academic emotions

Online presence in blended learning significantly positively predicted positive online academic emotions and significantly negatively predicted negative online academic emotions. The results of the present study are consistent with those of previous studies. Online presence includes teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence; among these, teaching presence had the most critical effect on online academic emotions. Previous studies have shown that instructional design can influence learners’ cognitive processing and learning outcomes by influencing emotional factors37. Teacher support is significantly related to students’ academic emotions, and these relationships are moderated by culture, age, and gender56. In an online learning environment, teachers’ online support is significantly negatively correlated with learners’ online learning anxiety levels32.

High-quality online learning resources can make learners more interested in learning; if online learning content and offline face-to-face content are connected to each other, learners will not feel bored due to repetition or feel complete disconnection, whereas too much repetition and minimal or no connection between online learning content and offline face-to-face content are likely to make learners feel distracted and bored. The long duration of boring video courses and a single learning environment can easily trigger negative emotions among learners35. Enhancement and emotional design of key elements on online learning screens have shown that the combination of anthropomorphic and colourful screen designs can significantly enhance learners’ mental effort and increase positive academic emotions52.

Research on social presence and academic emotions has shown that student‒student interactions allow students to feel the presence of classes and peers and that the sense of isolation in online learning is reduced36. Conversely, cognitive presence refers to the extent to which all learners in an online learning and inquiry community are able to coconstruct contexts and meanings during the learning and communication process23 and is influenced by instructional and social presence25. Previous studies have shown that both teaching presence and social presence, that is, the way teachers organize and guide instruction and the way they conduct discussions among their peers, affect academic emotions. Thus, it can be inferred that cognitive presence influences academic emotions.

Positive online academic emotions in blended learning were a positive predictor of learning performance, whereas negative online academic emotions were a negative predictor of learning performance. This result is largely consistent with the findings of previous studies. Positive academic emotions positively predict academic performance and influence the process and effectiveness of students’ continued learning and online interactions49,60. Students’ self-efficacy influences their academic emotions and metacognitive learning strategies, which in turn affect their academic performance40.

In a blended learning environment, positive-low arousal academic emotions mediate the relationship between online presence and learning performance. In other words, increased online presence may indirectly affect learning performance through the mediating variable of positive-low arousal academic emotions, supporting previous research. As online presence can influence online academic emotions, increased online presence implies the emergence of more positive-low arousal academic emotions and a decrease in negative academic emotions in blended learning. Since online academic emotions influence learning performance62, increasing online presence implies more positive-low arousal academic emotions, a decrease in negative academic emotions, and better academic performance in blended learning.

Limitations and further directions

First, the method of evaluating blended learning performance in this study was based on the results of students’ performance in cognitive, affective, skill, and behavioural aspects51, which included four indicators—communication ability, self-regulated learning ability, learning perseverance, and innovative thinking ability—but was not evaluated by students’ course grades. Future research could also add an assessment of student course grades and learning satisfaction to more fully evaluate blended learning performance. Second, this study used a cross-sectional research design; however, academic emotion is a complex psychological variable. Future research could use a longitudinal or experimental design and incorporate the interview method to explore the relationships among online academic emotions, online sense of presence, and learning performance in a blended learning environment. As learning engagement is also an important factor affecting learning performance, future research could explore the mechanism between learning engagement and online academic emotions, online sense of presence, and learning performance in a blended learning environment.

Conclusions

The results of this study show that in a blended learning environment, teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence all positively predict learning performance. By exploring the relationships among academic emotions, online presence, and learning performance in blended learning, this study revealed that (1) online presence significantly positively predicts positive online academic emotions and significantly negatively predicts negative online academic emotions; (2) positive online academic emotions positively predict learning performance, and negative online academic emotions negatively predict learning performance; and (3) positive-low arousal academic emotions mediate the relationship between online presence and learning performance.

Practical implications

This study constructed a theoretical model of the relationship between online presence and learning performance as mediated by online academic emotions in a blended learning environment. This theoretical model extends academic emotion research by examining how online academic emotions predict learning performance, how online presence predicts online academic emotions, and how online academic emotions mediate the effect of online presence on learning performance in blended learning. The model also explores the predictive role of online presence in learning performance, which improves the theoretical study of learning performance.

This study can help researchers understand the role of online academic emotions in how online presence influences learning performance. This study can provide a theoretical basis from the perspective of improving online academic emotions so that teachers can pay attention to the influence of online academic emotions on blended learning performance and serve as a theoretical reference for the further development and improvement of blended learning. In addition, from the perspective of teaching practice, this study has important implications for the instructional design of blended courses and for improving the teaching quality of blended learning. Teachers need to focus on reducing negative academic emotions and increasing positive-low arousal academic emotions during students’ online learning processes when implementing blended learning, which can improve learning performance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akyol, Z. & Garrison, D. R. Understanding cognitive presence in an online and blended community of inquiry: assessing outcomes and processes for deep approaches to learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 42 (2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01029.x (2011).

Arbaugh, J. B. How instructor immediacy behaviors affect student satisfaction and learning in Web-Based courses. Bus. Commun. Q. 64 (4), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056990106400405 (2001).

Artino, A. R. & Jones, K. D. Exploring the complex relations between achievement emotions and self-regulated learning behaviors in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 15 (3), 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.01.006 (2012).

Baker, R. S., D’Mello, S. K., Rodrigo, M. T. & Graesser, A. C. Better to be frustrated than bored: the incidence, persistence, and impact of learners’ cognitive-affective States during interactions with three different computer-based learning environments. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 68 (4), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.12.003 (2010).

Bernard, R. M. et al. A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Rev. Educ. Res. 79 (3), 1243–1289. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309333844 (2009).

Bralić, A. & Divjak, B. Integrating MOOCs in traditionally taught courses: achieving learning outcomes with blended learning. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 15 (2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0085-7 (2018).

Boling, E. C., Hough, M., Krinsky, H., Saleem, H. & Stevens, M. Cutting the distance in distance education: perspectives on what promotes positive, online learning experiences. Internet High. Educ. 15 (2), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.006 (2012).

Byrne, B. M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (Lawrence Erlbaum Press, 2001).

Cai, M. J., Tang, R. & Wei, Y. Research on online learning behavior of college students based on two-dimensional quadrant analysis: taking SPOC practices in blended learning environment as an example. e-Educ Res. 44 (08), 49–56 (2023).

Cao, W. A meta-analysis of effects of blended learning on performance, attitude, achievement, and engagement across different countries. Front. Psychol. 14, 1212056. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1212056 (2023).

Chai, H. Y. Learners’ listening behavior in asynchronous online discussions: measurement, aftereffects, antecedents, and a framework for designing supportive environments (Doctoral dissertation). Central China Normal University. (2020).

Chen, H. H. An analysis of influential factors on college students’ learning satisfaction in online courses (Master Dissertation). Nanjing Normal University. (2017).

Chen, H. L. & Chang, C. Y. Integrating the SOP2 model into the flipped classroom to foster cognitive presence and learning achievements. Educ. Technol. Soc. 20 (1), 274–291 (2017).

Chen, L. & Wang, Z. J. Principles of instructional interaction in three generations of distance education. China J. Distance Educ. 10, 30–37 (2016).

Cheng, L. T. W. & Wang, J. W. Enhancing learning performance through classroom response systems: the effect of knowledge type and social presence. Int. J. Manag Educ. 17 (1), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.01.001 (2019).

Dabbagh, N. The online learner: characteristics and pedagogical implications. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 7 (3), 217–226 (2007).

Dong, Y. & Yu, G. L. The development and application of an academic emotions questionnaire. Acta Psychol. Sinica. 39 (5), 852–860 (2007).

Ellis, R. A. & Bliuc, A. M. An exploration into first-year university students’ approaches to inquiry and online-learning technologies in blended environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 47 (5), 970–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12385 (2016).

Flynn, N. et al. Schooling at home’in Ireland during COVID-19’: parents’ and students’ perspectives on overall impact, continuity of interest, and impact on learning. Ir. Educ. Stud. 40 (2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916558 (2021).

Friedman, C. Students’ major online learning challenges amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pedagog Sociol. Psychol. 1 (1), 45–52 (2020).

Galikyan, I. & Admiraal, W. Students’ engagement in asynchronous online discussion: The relationship between cognitive presence, learner prominence, and academic performance. Internet High. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100692 (2019).

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T. & Archer, W. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2 (2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6 (1999).

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T. & Archer, W. Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. Am. J. Distance Educ. 15 (1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527071 (2001).

Hu, Y. & Zhao, F. M. Theoretical analysis model and measurement of online learning effectiveness. e-Educ Res. 36 (10), 37–45 (2015).

Jia, W. & Gao, X. Y. A community of inquiry model for blended learning of college English: An analysis of the mediating effects of emotional and social presence. Foreign Lang. World 4, 82–90 (2023).

Jiang, Z. H., Zhao, C. L., Li, H. X., Hu, P. & Huang, Y. Influencing factors of online learners’ satisfaction, comparison of live and recorded contexts. Open. Educ. Res. 23 (04), 76–85 (2017).

Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., Kovanović, V., Riecke, B. E. & Hatala, M. Social presence in online discussions as a process predictor of academic performance. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 31 (6), 638–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12107 (2015).

Kiuru, N. et al. The dynamics of motivation, emotion, and task performance in simulated achievement situations. Learn. Individ Differ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101873 (2020).

Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Guilford Press, 1998).

Kwon, K., Liu, Y. H. & Johnson, L. P. Group regulation and social-emotional interactions observed in computer supported collaborative learning: comparison between good vs. poor collaborators. Comput. Educ. 78, 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.004 (2014).

Le, C. Y. & Xu, R. H. The effectiveness, problems and deepening of online teaching in colleges and universities. Res. Educ. Dev. 40 (11), 18–24 (2020).

Li, A. An empirical study on the effect of online teacher support on college students’ learning anxiety (Master’s Dissertation), Shanxi Normal University. (2019).

Li, L., Gow, A. D. I. & Zhou, J. The role of positive emotions in education: A neuroscience perspective. Mind Brain Educ. 14 (3), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12244 (2020).

Liu, Z., Kong, X., Liu, S., Yang, Z. & Zhang, C. Looking at MOOC discussion data to uncover the relationship between discussion pacings, learners’ cognitive presence and learning achievements. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27 (6), 8265–8288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10943-7 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. A study of learners’ emotional characteristics and their relationship to learning effectiveness in SPOC forum interaction. China Educ. Technol. 04, 102–110 (2018).

Mu, S., Wang, X. J., Feng, G. Z. & Zhang, H. Design and implementation of interaction in synchronous online teaching. China Educ. Technol. 11, 52–59 (2020).

Park, B., Knörzer, L., Plass, J. L. & Brünken, R. Emotional design and positive emotions in multimedia learning: an Eyetracking study on the use of anthropomorphisms. Comput. Educ. 86, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.016 (2015).

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W. & Perry, R. P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37 (2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4 (2002).

Picciano, A. G. Beyond student perceptions: issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 6 (1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v6i1.1870 (2002).

Putwain, D., Sander, P. & Larkin, D. Academic self-efficacy in study-related skills and behaviours: relations with learning-related emotions and academic success. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 83 (4), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02084.x (2013).

Rapanta, C. et al. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigit Sci. Educ. 2 (3), 923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y (2020).

Rasheed, R. A., Kamsin, A. & Abdullah, N. A. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103701 (2020).

Shen, X. J. Research on blended learning design for deep learning of college students (Doctoral dissertation). Shanxi Normal University. (2021).

Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G. & Kindermann, T. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: part of a larger motivational dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 100 (4), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840 (2008).

Swan, K. Virtual interaction: design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Distance Educ. 22 (2), 306–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158791010220208 (2001).

Vanslambrouck, S. et al. An in-depth analysis of adult students in blended environments: do they regulate their learning in an old school way? Comput. Educ. 128 (1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.008 (2019).

Veldman, A., Van Kuijk, M. F., Doolaard, S. & Bosker, R. J. The proof of the pudding is in the eating? Implementation of cooperative learning: differences in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. Teach. Teach. 26 (1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1740197 (2020).

Villavicencio, F. T. Critical thinking, negative academic emotions, and achievement: a mediational analysis. Asia-Pac Educ. Res. 20 (1), 118–126 (2011).

Villavicencio, F. T. & Bernardo, A. B. I. Positive academic emotions moderate the relationship between self-regulation and academic achievement. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 83 (2), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02064.x (2013).

Walters, T., Simkiss, N. J., Snowden, R. J. & Gray, N. S. Secondary school students’ perception of the online teaching experience during COVID-19: the impact on mental wellbeing and specific learning difficulties. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 92 (3), 843–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12475 (2022).

Wang, J. X., Yuan, S. & Zhao, G. D. Impact of blended teaching on college students’ learning effectiveness: an empirical study based on the effect of MOOC application in top universities in China. Mod. Distance Educ. 05, 39–47 (2018).

Wang, X., Mayer, R. E., Han, M. & Zhang, L. Two emotional design features are more effective than one in multimedia learning. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 60 (8), 1991–2014. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331221090845 (2023).

Wertz, R. E. H. Learning presence within the Community of Inquiry framework: An alternative measurement survey for a four-factor model. Internet High. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2021.100832 (2022).

Wu, F., Chen, S. M. & Zhao, Z. N. A comparative study of college students’ learning engagement, learning time and learning performance: based on a survey of online and offline learning experiences of college students in Province F. China High. Educ. Res. 10, 22–27 (2022).

Wu, M. L. Structural equation modeling: The operation and application of AMOS (Chongqing University Press, 2010).

Xu, B. Mediating role of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 24705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75768-5 (2024).

You, J. W. & Kang, M. The role of academic emotions in the relationship between perceived academic control and self-regulated learning in online learning. Comput. Educ. 77, 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.04.018 (2014).

Zhang, W. L., Yu, X. & Liu, B. Design, implementation, and effectiveness analysis of leading online learning activities. e-Educ Res. 37 (10), 42–48 (2016).

Zhao, C. L., Li, H. X., Jiang, Z. H. & Huang, Y. Eliminating online learners’ burnout, a study on the impact of teachers’ emotional support. China Educ. Technol. 02, 29–36 (2018).

Zheng, H. H. & Liu, T. A study on the development of online independent learning ability of engineering students in the digital era: based on social presence theory. Res. High. Educ. Eng. 01, 92–97 (2023).

Zhou, H. & Long, L. R. Statistical tests and control methods for common method biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 06, 942–950 (2004).

Zhu, Y. et al. The impact of online and offline learning motivation on learning performance: the mediating effect of positive academic emotion. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27 (7), 8921–8938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10961-5 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to all the students who participated in this study. We also extend our sincere gratitude to Yan Li, Xuesong Zhai, Jing Wang, Licui Chen for their invaluable suggestions and insights contributed to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-Q. L. conducted the survey and wrote the manuscript. Y.-H. Y. reviewed and revised the manuscript. Both authors were responsible for the overall research design.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Education, Zhejiang University, China. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their parent/guardian. All procedures adhered to the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Ye, Y. Mediating role of online academic emotions between online presence and learning performance in blended learning environments. Sci Rep 15, 29875 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15947-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15947-0