Abstract

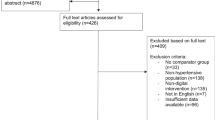

Despite the widespread use of antihypertensive medications, many patients struggle to achieve hypertension control, underscoring the need for additional strategies like lifestyle modification. Limited evidence exists on the impact of healthy lifestyle groups on hypertension control among individuals taking or not taking medication. This study assessed the effect of healthy lifestyle categories and scores on blood pressure control, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) among hypertensive adults in Iran. Data from the 2021 nationwide STEPwise Approach to non-communicable disease Risk Factor Surveillance survey were analyzed. Lifestyle variables, including physical activity, body mass index, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and dietary habits, were scored for 9388 hypertensive adults ≥ 18 years across rural and urban regions from 2016 to 2021. Multivariable analysis, adjusted for antihypertensive medication use, showed that moderate and good lifestyle groups were associated with 9% (OR 0.91 [95% CI 0.85–1.04]) and 15% (OR 0.85 [95% CI 0.72–1.01]) lower odds of uncontrolled hypertension, respectively. These groups also significantly lowered SBP by − 1.22 (− 2.16 to − 0.23) and − 1.39 (− 2.54 to − 0.26) mmHg and DBP by − 1.01 (− 1.62 to − 0.41) and − 1.47 (− 2.21 to − 0.73) mmHg. These findings emphasize the potential of lifestyle interventions as part of public health strategies for blood pressure control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

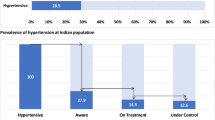

Hypertension, the most prominent non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factor, is the leading cause of overall mortality and disability worldwide, with a global burden of approximately 10 million deaths and 200 million years of healthy life lost annually1. According to the latest World Health Organization report in 2023, the number of hypertensive adults (systolic blood pressure [SBP] ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure [DBP] ≥ 90 mmHg) has doubled since 1990, reaching 1.3 billion individuals in 2019. Nearly half of hypertensive adults are aware of their hypertension status, around 40% are receiving treatment, and controlled hypertension is achieved in only about 20% of adults2. Reports in Iran have estimated that about 25% of Iranians are affected by hypertension3. Therefore, given the heavy global and regional burden of hypertension, identifying effective approaches for its management is critical.

Hypertension management relies not only on pharmacologic interventions but also on sustained lifestyle modification4. A healthy lifestyle—defined by regular physical activity, maintaining a normal body mass index (BMI), avoiding tobacco and excessive alcohol use, and adhering to a balanced diet—has consistently been associated with lower blood pressure levels and improved overall cardiovascular health5,6,7. Healthy lifestyle changes, even minor improvements, can effectively contribute to lowering blood pressure. Unfortunately, in many instances, following a healthy lifestyle may be challenging or insufficient, and a majority of patients do not adhere to lifestyle modification after diagnosis, which ultimately necessitates the use of antihypertensive medications8,9. One behavioral factor for nonadherence may be patients lacking motivation or support to maintain lifestyle changes, especially if they do not immediately see the benefits of such adjustments7. Notably, studies have shown that individuals on antihypertensive medications often display poorer lifestyle habits than those untreated, suggesting a possible overreliance on pharmacologic therapy10. Uncontrolled hypertension rates despite treatment reach 26% worldwide, further highlighting the crucial role of healthy lifestyle changes in early prevention and hypertension management.

Evidence regarding the combined effect of multiple lifestyle behaviors on hypertension control is limited11,12,13,14, especially in the context of accounting for antihypertensive medication use. . While some studies have investigated the role of individual lifestyle factors on blood pressure, fewer have evaluated their collective impact using comprehensive lifestyle scores15,16. Furthermore, the interplay of these behaviors is rarely explored in both treated and untreated populations. Given that several risk factors often coexist and compound health outcomes, a composite lifestyle index may better capture their cumulative influence on hypertension management17. Also, while prior studies have reported associations between lifestyle scores and hypertension control, few have included SBP and DBP as continuous outcomes. Overall, there is a need for large studies on this topic, both globally and regionally in Iran.

Based on the nationwide STEPwise Approach to NCD Risk Factor Surveillance (STEPS) method by the World Health Organization, STEPS studies have been conducted on national and subnational levels in Iran since 2005 to collect and analyze detailed data on NCD risk factors in order to provide valuable input for healthcare administrators. Iran presents a particularly urgent context for studying hypertension due to growing urbanization, shifting dietary patterns, and difficulties in accessing healthcare. While previous studies in Iran16,18 have examined the relationship between lifestyle factors and hypertension, this study builds on prior work by using 2021 STEPS data to explore temporal changes and extends the analysis by assessing the association of healthy lifestyle scores and categories with SBP and DBP, as well as hypertension control, among treated and untreated hypertensive adults (both aware and unaware of their condition).

Methods

Study design and participants

We obtained data from the 2021 nationwide STEPS survey conducted by the NCD Research Center in Iran. The detailed design protocol and methodology of the STEPS study 2021 have been described elsewhere19. Briefly, the World Health Organization introduced the STEPS studies according to its framework for NCD risk factors surveillance, assessment, and reporting. In Iran, the STEPS national surveys were first implemented in 2005 with eight follow-up rounds, with the latest survey being carried out in 2021.

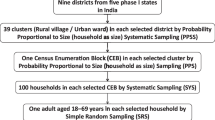

The STEPS 2021 study utilized a systematic cluster classification method to calculate the sample size. After using a proportion-to-population size method, 3176 clusters were calculated to conduct this national survey, with 10 participants in each cluster (reduced to 9 due to COVID-19 restrictions in some clusters). The survey collected demographic, lifestyle behaviors, and metabolic information through three steps: (1) questionnaires (n = 27,874) (2) physical (n = 27,745) and (3) laboratory measurements (n = 18,119).

In this study, we included adults ≥ 18 years with self-reported hypertension, SBP ≥ 140, DBP ≥ 90, or antihypertensive medication use, who resided in rural and urban regions of 31 provinces in Iran (n = 9561). Individuals with severe mental or physical disabilities unable to answer the questionnaires or participate in anthropometry measurements; individuals who refused to provide laboratory samples; and pregnant women were excluded from the study. As illustrated in Fig. 1, after excluding cases with missing values, 9388 patients were included in the final analysis.

Questionnaires

The STEPS questionnaire is primarily based on the standard tool created by World Health Organization, specifically utilizing the most recent version (version 3.2)20. This questionnaire has consisted of two main sections: core questions and expanded questions. This survey incorporated all core questions along with a majority of the expanded questions, which cover areas such as demographics, dietary habits, physical activity, and tobacco usage.

Physical measurements

Weight was recorded using a calibrated digital scale (Inofit), which was adjusted with a 5 kg reference weight each time it was moved. Height was assessed using a standard meter stick while the individual stood straight against a wall, ensuring that their heels, hips, and the back of their head were aligned with the wall. Blood pressure readings were taken in three separate rounds from the brachial artery, with each round separated by a three-minute interval. This process started after a 15-min rest period in a seated position, utilizing standard Beurer sphygmomanometers. The final blood pressure value was determined by averaging the second and third measurements.

Variables

We adopted five lifestyle factors, namely, physical activity, BMI, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and dietary habits, to create a healthy lifestyle behavior score. Each lifestyle factor was classified into different levels based on a predetermined criteria, and patients were assigned points for each level. The full description of the criteria and scoring are outlined in Supplementary Table S1. In brief, physical activity was defined as total recreational and travel time in minutes per week and scored in tertiles; BMI was categorized with ≤ 24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 values21; alcohol consumption and tobacco use were classified based on individuals’ history of use as current, former, or never; and dietary habit items such as, mean fruits and vegetables intake were calculated from servings/day * days per week divided by 7, dairy products, and other nutritional variables including dairy type (based on fat content), red meat, fish, processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, salt intake, high-salt processed foods, main meal, snack, breakfast, whole grains, nuts, and nutrition facts label were scored based on frequency of consumption determined by expert opinion. Then we calculated a healthy lifestyle behavior score from the sum of all five lifestyle factor points for each patient. Using the tertile system, the healthy lifestyle behavior score (minimum score 0 to maximum 9) was divided into three groups of poor, moderate, and good lifestyle behavior for the first to third tertile, respectively. We then examined the relationship of each lifestyle behavior category and the trend of scores from 0 to 9 with the study outcomes.

The study outcomes consisted of uncontrolled hypertension, SBP, and DBP levels. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, self-reported, diagnosed during physical assessment, or using antihypertensive medication. Patients diagnosed by a physician or using medication were classified as the aware group. Additionally, we defined controlled hypertension as SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg1.

Ethical approval

All individuals gave informed consent to the study conditions before participation, and the Research Council and Medical Ethics Committee at the Endocrine and Metabolism Research Institute approved the 2021 STEPS study protocol (IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1403.071). All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

The weighting process was done based on the age, sex, and area stratifications at the provincial level of the 2016 Iranian census, which the detailed process is described elsewhere19,22, and the nonresponse rate was considered in statistical analyses. After that it was cleared of unusual values. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables were presented as proportions and confidence intervals (CI), and numerical variables were described in terms of weighted means and corresponding CI. The chi-square test was used to compare all categorical variables pairwise (e.g., sex and lifestyle index). In addition, an independent t-test was used to show the difference between the means of the numerical variables.

Logistic regression was performed to assess the association between healthy lifestyle as an independent variable (in three levels: poor, moderate, and good) and uncontrolled hypertension as an outcome. First, the univariable model was run to illustrate the crude odds ratio (OR). Subsequently, the age- and sex-adjusted model and the fully adjusted model were created to control for the effects of potential confounders. In addition, the linear regression model was performed to examine the relation between a healthy lifestyle and mean SBP and DBP. As mentioned above, crude and adjusted models were created to control for confounding factors. A stepwise regression model with backward approach was used to select variables for the adjusted models. Therefore, all potential covariates were entered in model firstly, and then, variables with p-values under 0.20 were retained in the model and selected as covariates for adjustment23. The final covariates in the fully adjusted models were: age, sex, education, hypertension medication use, hypertension status, comorbidity, and marital status. To evaluate multicollinearity between the independent variables, the variance inflation factor criteria were tested in all models. The average variance inflation factor was below 5, indicating that there was no collinearity between the variables24.

Cases with missing values were dropped, and all analyses were performed using the complete cases strategy, as missing data did not significantly alter the results under sensitivity analysis with amputated data. Stata version 18 was used to analyze the data. The level of confidence was set at 95%, and p < 0.05 was assumed as a statistically significant.

Results

We found good lifestyle status to be significantly more prevalent in males, single individuals, urban residents, those with higher education (> 12 years), retired individuals, and individuals with basic health insurance (all p-values < 0.05). Also, patients with good lifestyle status recorded lower mean DBP than patients with poor lifestyle (85.1 [95% CI 84.5–85.7] vs. 86.6 [95% CI 86.1–87.1] mmHg; p-value = 0.042) (detailed statistical results are shown in Table 1).

As outlined in Table 2, unaware patients (23.2% [95% CI 21.6–24.8]) tended to adopt good lifestyle more than aware patients taking medication (19.9% [95% CI 18.7–21.3]) (p-value < 0.001). Conversely, aware individuals not taking antihypertensive medication reported poor lifestyle (39.5% [95% CI 36.7–42.4]) more than unaware individuals (34.2% [95% CI 32.4–35.9]; p-value < 0.001).

Regarding healthy lifestyle factors, aware patients taking medication had much poorer levels of physical activity (51.6% [95% CI 50.0–53.2]) and had a higher BMI (≥ 30.0 kg/m2) (41.8% [95% CI 40.2–43.5]) compared with patients not taking medication (40.6% [95% CI 37.8–43.5] and (35.1% [95% CI 32.3–37.9], respectively) and unaware patients (44.2% [95% CI 42.4–46.1] and (33.5% [95% CI 31.7–35.3]), respectively). Aware patients under no antihypertensive medication quit smoking more often than the others (34.9% [95% CI 32.2–37.7] vs 28.2% [95% CI 26.7–29.6] in patients taking medication and 28.3% [95% CI 26.6–29.9] in unawares). Also, aware patients who took medication consumed less alcohol (3.8% [95% CI 3.2–4.6]) than aware patients not taking medication (8.9% [95% CI 7.4–10.8]) and unawares (7.1% [95% CI 6.2–8.2]). Furthermore, aware patients with medication had the least number of current smokers among all groups (9.3% [95% CI 8.4–10.3]). Lastly, good dietary habits were more common in aware patients taking medication (37.1% [95% CI 35.5–38.7]) than in aware patients not taking medication (31.2% [95% CI 28.6–34.0]) and patients unaware of their condition (33.6% [95% CI 31.8–35.4]).

As depicted in Fig. 2, among treated patients, uncontrolled hypertension was most prevalent in patients with poor lifestyles (59.9%) and the least in those with good lifestyles (55.5%). Similarly, among patients not taking medication, 46.6% of patients with poor lifestyles and 44.1% with good lifestyles had uncontrolled hypertension, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Our multivariable linear and logistic regression regarding the relationship between healthy lifestyle categories and uncontrolled hypertension, SBP, and DBP is presented in Table 3. Although statistically insignificant, in the fully adjusted model, aware patients with moderate and good lifestyles were 9% and 15% more likely to achieve controlled hypertension compared to those with poor lifestyles (OR 0.91 [95% CI 0.85–1.04] and OR 0.85 [95% CI 0.72–1.01], respectively). Moreover, a 1-unit increase in healthy lifestyle score was related to an 8% decrease in the chance of uncontrolled hypertension, although not statistically significant (OR 0.92 [95% CI 0.85–1.00]). Adherence to a good lifestyle was associated with a decrease in SBP (β coefficient: − 1.39 [95% CI − 2.54 to − 0.26]; p-value = 0.016) and DBP (β coefficient: − 1.47 [95% CI − 2.21 to − 0.73]; p-value < 0.001) in the total population. Also, a healthy lifestyle score trend was found to lower SBP (β coefficient: − 0.75 [95% CI − 1.31 to − 0.20]; p-valuetrend = 0.008) and DBP (β coefficient: − 0.76 [95% CI − 1.13 to − 0.41]; p-valuetrend < 0.001) per unit increase.

Discussion

Our findings suggest a trend indicating the influence of healthy lifestyle score trends and categories on control of hypertension, SBP, and DBP levels. Although we did not find a statistically significant difference, improving and achieving a higher lifestyle score was tied to better hypertension control and reduction in SBP and DBP.

Our results indicated a non-significant inverse trend, independent of antihypertensive medication use, between healthy lifestyle score trends and categories and uncontrolled hypertension. Our observations are consistent with other studies in the literature. A cross-sectional study on 311,994 hypertensive individuals found higher healthy lifestyle scores and healthier lifestyles to reduce the risk of uncontrolled hypertension15. A randomized community intervention trial conducted in rural China on patients with hypertension showed higher rates of blood pressure control (56%) by lifestyle interventions as well as improved biochemical and physiological results compared with the control group after one year of lifestyle intervention25. Akbarpour et al.16 surveyed 2577 hypertensive patients and found a 37% lower risk of uncontrolled hypertension in patients who followed a moderate healthy lifestyle; however, this study did not examine the association of a healthy lifestyle score with hypertension control, and similar to our study, no statistically significant relationship was found between a good healthy lifestyle and uncontrolled hypertension. These statistically insignificant findings could pertain to a small sample size compared to other studies with significant results15. A longitudinal analysis of the FRESH study conducted in Japan revealed that a change in lifestyle from unhealthy to healthy was associated with a 46% lower risk of failure to achieve controlled hypertension compared to those who did not alter their unhealthy lifestyle behaviors13. This evidence highlights the crucial role of lifestyle modification in the effective management of hypertension. This takes greater significance as following a healthy lifestyle and improvements in healthy lifestyle scores reduce the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients26. Our non-significant results could be attributed to several factors. We have not gathered data on patients’ compliance with antihypertensive medication use; therefore, irregular usage may have contributed to this result. In addition, individuals taking medication are likely to have recorded higher levels of blood pressure compared to those who do not take medication. Thus, lifestyle changes may have a limited impact on managing the hypertension of those taking medication, as they still might require it.

Our analysis showed that a healthier lifestyle lowers the SBP and DBP independent of antihypertensive medication use. This is on par with an analysis of the UK Biobank study that found participants with favorable and higher healthy lifestyle scores to have around 4–5 mmHg lower SBP than those with unfavorable and low healthy lifestyle scores27. Although the UK Biobank study assessed the association of each lifestyle risk factor with blood pressure levels, it failed to reflect the impact of healthy lifestyle categories on blood pressure changes and sufficed to present this relation quantitatively. They also made no adjustments for antihypertensive medication in their analysis and calculated healthy lifestyle scores without including the smoking variable. In another study, SBP and DBP were decreased by 4.32 mmHg and 1.96 mmHg, respectively, in patients within healthier lifestyle clusters; however, these clusters were mainly focused on one or two lifestyle risk factors rather than a combination of them, which led to paradoxical results in some instances. This differs from our approach of presenting the combined effect of lifestyle risk factors on blood pressure changes18. Similarly, a healthier Mediterranean lifestyle status (only including physical activity and dietary items) managed to significantly decrease nighttime SBP by 3.17 mmHg28. A meta-analysis29 revealed that interventions led by healthcare professionals, including lifestyle modifications, effectively lowered SBP by 5 mmHg. Unlike other studies, our study investigated the association of healthy lifestyle groups and scores on blood pressure changes in one comprehensive analysis, and not all studies included major lifestyle factors in developing a healthy lifestyle index.

Lifestyle modification remains the first step in hypertension management, and patients’ awareness of their disease affects their lifestyle choices30. In our study, aware individuals not taking medication demonstrated better lifestyles compared with those taking medication, although this difference was small. Akbarpour et al.16 also reported better lifestyle choices in aware individuals without medication use compared with those using medication. This can be explained by the fact that patients taking medication may rely solely on antihypertensive drugs and do not feel prompted to make adjustments to their lifestyle patterns, as it is a cumbersome task to follow healthy lifestyle decisions for a long time31.

It is anticipated that patients who are aware of their condition will adjust their lifestyle patterns or exhibit behaviors that differ from unaware individuals. Surprisingly, we found a significant difference between unaware and aware patients regarding their lifestyle behaviors; this is suggested in other studies16,32,33, which was not statistically significant. Our results showed unaware individuals followed healthier lifestyle patterns compared with aware individuals. This is contradictory to the results of other studies that suggested a higher prevalence of better lifestyle choices in aware subjects14,34. A few reasons may have contributed to this finding. Firstly, patients unaware of their hypertension may not experience the anxiety or stress associated with their diagnosis. This lack of concern can lead to a more relaxed approach to life, potentially resulting in healthier lifestyle choices, such as regular physical activity, compared to those who are burdened by the knowledge of their condition and its implications7. Secondly, constant monitoring of health and adherence to strict lifestyle modifications may be overwhelming for some individuals, which can lead to a decline in adherence to healthy behaviors over time, while those unaware may continue with a more flexible and less restricted lifestyle. Thirdly, the self-reported status of adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors in individuals aware of their disease may be exaggerated, which influences the results of the studies that yielded results contrary to ours34.

Unexpectedly, our results indicated unaware patients have higher rates of physical activity and lower BMI than aware patients. This significant difference has been reported in some studies16,32,35, while others have found small and opposing results14. As mentioned earlier, unawareness of disease diagnosis may lead to less stressful and healthier lifestyle habits. Moreover, age may be a contributing factor, as unaware individuals are generally younger than those who are aware and thus physically more active16. Obesity is a significant factor that may contribute to the development of hypertension, particularly before an individual is diagnosed, which could increase the likelihood of being diagnosed with hypertension in obese individuals32. Unaware patients were more likely to be current smokers, as seen in other reports16 and most ex-smokers in our study were aware untreated patients, which could pertain to their attempt to modify their lifestyle choices. Overall, we found that aware patients with medication use significantly adhere to better lifestyle choices than unaware patients, except for BMI and physical activity. Other studies14,35 have also discovered aware individuals to have a healthier status for smoking, alcohol consumption, and salt intake compared to those unaware of their disease, but not for the other healthy lifestyle recommendations in which no significant difference was detected.

To promote healthier lifestyles, we suggest developing national guidelines that integrate lifestyle modification counseling into primary care settings while implementing community-based programs focused on promoting physical activity and healthy eating. Additionally, providing training for healthcare professionals on effective communication techniques will further encourage lifestyle changes among patients. Furthermore, proposing policies that support environments conducive to healthy living, such as the creation of more public recreational spaces, will enhance these efforts and foster a culture of wellness in communities.

The main strengths of our study were the inclusion of both treated and untreated patients, the examination of healthy lifestyle score trends, and the quantitative impact of lifestyle on blood pressure. National data gathering, sampling techniques, few missing data, and also a large sample size enhanced the study’s representativeness.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, it lacks information on some dietary variables, such as oil consumption and the salt intake amount, which may impact the accuracy of our findings regarding dietary influences on hypertension. We attempted to compensate for this by using the type of dairy products and self-impression of salt intake. Secondly, our healthy lifestyle score needs to be further evaluated and validated by other studies, especially cohort investigations. Thirdly, because of the cross-sectional study design, we could not establish any causality. Fourthly, as this study is based on a self-reported questionnaire, the results could be subject to recall bias. Future research should focus on incorporating a broader range of dietary variables and exploring the long-term effects of lifestyle interventions on hypertension management.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that adherence to a healthier lifestyle can effectively impact the control of hypertension, independent of antihypertensive medication use, and can reduce SBP and DBP. Although not all findings reached statistical significance, the observed trends still hold practical importance for hypertension management. Given these findings, healthcare policymakers should prioritize the promotion of lifestyle modification as a critical component of hypertension management through education, patient training, and involving healthcare providers to enhance public health outcomes. Further prospective studies are needed to validate our findings and evaluate the effect of lifestyle changes on hypertension management in hypertensive individuals.

Data availability

The corresponding author will readily share the raw data that supports the conclusions of this article upon request.

References

World Health Organization. Global Report on Hypertension: The Race Against a Silent Killer (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2023). https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/372896

Kario, K., Okura, A., Hoshide, S. & Mogi, M. The WHO Global report 2023 on hypertension warning the emerging hypertension burden in globe and its treatment strategy. Hypertens. Res. 47, 1099–1102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01622-w (2024).

Oori, M. J. et al. Prevalence of HTN in Iran: Meta-analysis of Published Studies in 2004–2018. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 15, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573402115666190118142818 (2019).

Oparil, S. et al. Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 18014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.14 (2018).

Barbaresko, J., Rienks, J. & Nöthlings, U. Lifestyle indices and cardiovascular disease risk: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 55, 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.046 (2018).

Baena, C. P. et al. Effects of lifestyle-related interventions on blood pressure in low and middle-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 32, 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000000136 (2014).

Ojangba, T. et al. Comprehensive effects of lifestyle reform, adherence, and related factors on hypertension control: A review. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 25, 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14653 (2023).

Nguyen, Q., Dominguez, J., Nguyen, L. & Gullapalli, N. Hypertension management: An update. Am. Health Drug Benefits 3, 47–56 (2010).

Silva, B. V., Sousa, C., Caldeira, D., Abreu, A. & Pinto, F. J. Management of arterial hypertension: Challenges and opportunities. Clin. Cardiol. 45, 1094–1099. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23938 (2022).

Neutel, C. I. & Campbell, N. Changes in lifestyle after hypertension diagnosis in Canada. Can. J. Cardiol. 24, 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70584-1 (2008).

Setiadi, A. P. et al. Knowing the gap: Medication use, adherence and blood pressure control among patients with hypertension in Indonesian primary care settings. PeerJ 10, e13171. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13171 (2022).

Cherfan, M. et al. Unhealthy behaviors and risk of uncontrolled hypertension among treated individuals-The CONSTANCES population-based study. Sci. Rep. 10, 1925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58685-1 (2020).

Yokokawa, H. et al. Association between control to target blood pressures and healthy lifestyle factors among Japanese hypertensive patients: Longitudinal data analysis from Fukushima Research of Hypertension (FRESH). Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 8, e364–e373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2013.08.004 (2014).

Scheltens, T. et al. Awareness of hypertension: Will it bring about a healthy lifestyle?. J. Hum. Hypertens. 24, 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2010.26 (2010).

Dong, T. et al. Association of healthy lifestyle score with control of hypertension among treated and untreated hypertensive patients: a large cross-sectional study. PeerJ 12, e17203. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17203 (2024).

Akbarpour, S. et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and control of hypertension among adult hypertensive patients. Sci. Rep. 8, 8508. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26823-5 (2018).

Khaw, K. T. et al. Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: The EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med 5, e12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050012 (2008).

Akbarpour, S. et al. Relationship between lifestyle pattern and blood pressure—Iranian national survey. Sci. Rep. 9, 15194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51309-3 (2019).

Djalalinia, S. et al. Protocol design for surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: An experience from Iran STEPS survey 2021. Arch. Iran. Med. 25, 634–646. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2022.99 (2022).

World Health Organization. The WHO STEPwise Approach to Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factor Surveillance (STEPS): WHO STEPS Instrument (Core and Expanded) (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2015). https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/steps/instrument

World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 894, i–xii, 1–253 (2000).

Population and Housing Censuses, https://amar.org.ir/english/Population-and-Housing-Censuses (2016).

Bursac, Z., Gauss, C. H., Williams, D. K. & Hosmer, D. W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 3, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 (2008).

Kim, J. H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 72, 558–569. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19087 (2019).

Xiao, J. et al. Effectiveness of lifestyle and drug intervention on hypertensive patients: A randomized community intervention trial in rural China. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 3449–3457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05601-7 (2020).

Lu, Q. et al. Association of lifestyle factors and antihypertensive medication use with risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality among adults with hypertension in China. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2146118–e2146118. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46118 (2022).

Pazoki, R. et al. Genetic predisposition to high blood pressure and lifestyle factors. Circulation 137, 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030898 (2018).

Talavera-Rodríguez, I. et al. Mediterranean lifestyle index and 24-h systolic blood pressure and heart rate in community-dwelling older adults. GeroScience 46, 1357–1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00898-z (2024).

Treciokiene, I. et al. Healthcare professional-led interventions on lifestyle modifications for hypertensive patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 22, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01421-z (2021).

Chobanian, A. V. et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 289, 2560–2572. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 (2003).

Schutte, A. E., Srinivasapura Venkateshmurthy, N., Mohan, S. & Prabhakaran, D. Hypertension in low- and middle-income countries. Circ. Res. 128, 808–826. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.318729 (2021).

Kim, Y. & Kong, K. A. Do Hypertensive individuals who are aware of their disease follow lifestyle recommendations better than those who are not aware?. PLoS ONE 10, e0136858. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136858 (2015).

Diendéré, J. et al. A comparison of unhealthy lifestyle practices among adults with hypertension aware and unaware of their hypertensive status: Results from the 2013 WHO STEPS survey in Burkina Faso. BMC Public Health 22, 1601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14026-7 (2022).

Gee, M. E. et al. Prevalence of, and barriers to, preventive lifestyle behaviors in hypertension (from a national survey of Canadians with hypertension). Am. J. Cardiol. 109, 570–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.051 (2012).

Banegas, J. R. et al. Achievement of cardiometabolic goals in aware hypertensive patients in Spain: A nationwide population-based study. Hypertension 60, 898–905. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.112.193078 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Iran’s National Institute of Health Research, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Contract NO: 241/M/9839. We appreciated the aid of all colleagues in the NCD Research Center and the Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute (EMRI) at Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

This work was supported by the Endocrinology and Metabolism Population Sciences Institute at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran (Grant ID 1403–2-221–73074). The funding sources did not influence any aspect of the study’s design, implementation, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.A.; Methodology: S.A., L.A., K.K.; Formal analysis: K.K.; Investigation: N.R., M.M., A.G., S.K., A.V., K.K.; Resources: S.A. and L.A.; Data Curation: K.K., N.R., S.K., M.M., A.G.; Validation: K.K., N.R., S.K., M.M., A.G.; Writing—Original Draft: A.V., K.K.; Writing—Review and Editing: S.A., L.A., N.R., S.K., M.M., A.G., A.V., K.K.; Supervision: S.A. and L.A.; Project administration: S.A. and L.A.; Funding acquisition: S.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval of this study was granted by the Research Ethics Committees of Endocrine and Metabolism Research Institute—Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1403.071). Participants provided their written informed consent to take part in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaezi, A., Karimi, K., Mirzad, M. et al. The role of healthy lifestyle categories and score trend in managing hypertension among hypertensive adults. Sci Rep 15, 31194 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16024-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16024-2