Abstract

This research investigates the impact of bacterial growth on the pH of culture media, emphasizing its significance in microbiological and biotechnological applications. A range of sophisticated artificial intelligence methods, including One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Decision Tree (DT), Ensemble Learning (EL), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Random Forest (RF), and Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LSSVM), were utilized to model and predict pH variations with high accuracy. The Coupled Simulated Annealing (CSA) algorithm was employed to optimize the hyperparameters of these models, enhancing their predictive performance. A robust dataset comprising 379 experimental data points was compiled, of which 80% (303 points) were used for training and 20% (76 points) for testing. The study focuses on three bacterial strains including Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, and Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922 cultured in Luria Bertani (LB) and M63 media, across varying initial pH levels, time intervals, and bacterial cell concentrations (OD600). Key input variables for the models included bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time (hours), and bacterial cell concentration, all critical to pH dynamics. Sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulations revealed bacterial cell concentration as the most influential factor, followed by time, culture medium type, initial pH, and bacterial type. The dataset was rigorously validated before training to ensure its suitability for predictive modeling. Evaluation of model performance demonstrated that the 1D-CNN model exhibited enhanced predictive precision, attaining the minimal RMSE and the maximum R² values and MAPE percentages in both training and testing phases. These findings underscore the efficacy of artificial intelligence techniques, particularly 1D-CNN, in precisely predicting pH changes in culture media due to bacterial growth. This methodology provides a reliable, cost-effective, and efficient alternative to traditional experimental approaches, enabling researchers to forecast pH behavior with greater confidence and reduced experimental effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintaining pH homeostasis plays a crucial role in cellular metabolism, and its significance becomes evident through multiple biochemical and physiological lenses1,2. One key aspect is that the structure and function of biomacromolecules particularly proteins and enzymes are highly sensitive to pH, as even minor deviations can lead to conformational changes that impair biological activity3. Furthermore, pH directly influences the kinetics and thermodynamics of many metabolic reactions, especially those involving proton transfer, thus governing the directionality and efficiency of crucial biochemical pathways4. Notably, pH fluctuations can substantially affect energy metabolism, as the proton motive force is central to ATP synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation5. In the context of bacterial growth, understanding how microbial metabolism alters the pH of culture media is vital not only for optimizing growth conditions in industrial and clinical microbiology but also for elucidating microbial interactions, biofilm formation, and pathogenesis. Modeling these dynamics provides critical insights into microbial ecology and supports the development of pH-controlled bioprocesses and therapeutic strategies6.

In eukaryotic cells, molecular mechanisms are in place to regulate intracellular pH within a specific range across different subcellular compartments. For instance, mitochondria and chloroplasts are surrounded by cytoplasm, which tightly controls pH homeostasis. In contrast, bacteria thrive in a wide variety of environments, and the pH of their surroundings shapes their lifestyle, forming the basis for categorizing them as acidophiles (pH 1–3), alkaliphiles (pH 10–13), or neutrophiles (pH 5.5–9). Nevertheless, like eukaryotes, bacteria generally maintain a near-neutral intracellular pH to support metabolic activity and preserve cellular integrity. Their ability to regulate pH involves a range of mechanisms to sense and adapt to extracellular pH fluctuations7. Several factors can influence environmental pH changes. The initial pH and composition of the growth medium play a fundamental role, followed by the bacterial growth phase and the organism’s physiology and optimal pH range. In addition, microbial metabolism itself can alter extracellular pH. As a result, the growth of one bacterial strain may impact the proliferation of neighboring strains in a shared ecosystem, potentially shaping the fate of entire microbial populations8.

Understanding pH homeostasis in this context can offer practical applications in fields such as bioremediation or the study of pathogenic bacterial behavior. While many studies have explored the effects of initial pH on bacterial growth or specific metabolite production, fewer have focused on how pH evolves during microbial growth. The aim of the present study was to describe and elucidate pH changes throughout bacterial growth and to identify the factors driving these changes. As a proof of concept, we demonstrated that in silico predictions of pH shifts using a well-curated genome-scale metabolic model of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 are consistent with experimentally observed pH dynamics, at least in media containing glucose, glycerol, or citrate as carbon sources9. Sánchez-Clemente and team studied pH effects on growth and extracellular pH changes in Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344, selected for cyanide assimilation under alkaline conditions. They tested initial pH (6, 7, 8 for E. coli and P. putida; 7.5, 8.25, 9 for P. pseudoalcaligenes) in LB-medium, noting pH convergence to strain-specific values by stationary phase10. In glucose minimal medium, Pseudomonadaceae pH remained stable, but E. coli’s pH dropped to 4.5 at initial pH 6, stopping growth, though higher pH allowed recovery. Carbon sources affected pH: glucose and glycerol stabilized it, while citrate caused alkalinization, matching P. putida KT2440 model predictions.

The observed pH fluctuations during bacterial growth can be attributed to the metabolic activities of the microorganisms, which modulate their surrounding environment through the consumption of nutrients and the excretion of metabolites. For instance, species like Lactobacillus plantarum produce lactic acid as a metabolic by-product, thereby reducing the medium pH, while others such as Corynebacterium ammoniagenes produce ammonia via urease activity, which increases the pH of the medium11. These opposing mechanisms contribute to a diverse range of pH shifts depending on the bacterial strain and the availability of carbon and nitrogen sources such as glucose and urea.

Furthermore, the impact of these metabolic products on bacterial viability can manifest as beneficial (positive feedback) or detrimental (negative feedback) effects. For example, the accumulation of alkaline metabolites by Pseudomonas veronii despite its preference for acidic environments can lead to a phenomenon known as ecological suicide, where the population inadvertently alters the pH beyond its tolerance range, resulting in its own extinction11. These feedback mechanisms illustrate how metabolic pathways intricately influence pH dynamics, supporting the predictive capacity of data-driven models like CNN in capturing the nonlinear relationship between bacterial growth and environmental pH. Incorporating such metabolic insights aligns the modeling outcomes with known biochemical behaviors and strengthens the interpretability of the predictions.

Collectively, experimental research has generated a robust dataset elucidating the pH dynamics of culture media influenced by bacterial growth under diverse conditions. These data serve as vital inputs for microbiological modeling and process optimization, while also facilitating data-driven predictive approaches, such as artificial intelligence, to enhance the efficiency of pH prediction with reduced experimental demands.

While prior studies have examined the pH changes in culture media due to bacterial activity, comprehensive datasets encompassing various bacterial strains and media types remain limited. Consequently, there is a pressing need to systematically gather extensive pH data across different bacterial types, culture media, initial pH levels, time intervals, and bacterial cell concentrations. Given the critical role of pH in microbiological processes and biotechnological applications, accurately predicting pH variations in culture media presents a complex challenge due to the interplay of factors such as bacterial type, culture medium, initial pH, time, and cell concentration. The pH of culture media is a key parameter in optimizing microbial growth conditions, bioreactor design, and bioprocess development, highlighting the necessity for precise pH predictions in practical applications. Traditional experimental methods for measuring pH, although dependable, are often resource-intensive and time-consuming, necessitating advanced computational techniques capable of providing rapid and reliable predictions.

This study bridges this gap by employing a suite of artificial intelligence models, including One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Decision Tree (DT), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Random Forest (RF), Ensemble Learning (EL), and Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LSSVM), to simulate and predict pH variations in Luria Bertani (LB) and M63 media influenced by three bacterial strains: Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344. To optimize the performance of these models, their hyperparameters were fine-tuned using the Coupled Simulated Annealing (CSA) algorithm. The models were developed and validated using a comprehensive dataset comprising 379 experimental data points, with 303 allocated for training (80%) and 76 for testing (20%). Thorough dataset validation ensured its suitability for predictive modeling, while sensitivity analysis via Monte Carlo simulations assessed the impact of each input parameter on pH outcomes. Model performance was meticulously evaluated using statistical metrics and visual representations, identifying the 1D-CNN model as the most accurate in predicting pH changes. The overall research methodology is depicted in Fig. 1.

Although various artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have been successfully applied in microbial systems, the modeling of pH dynamics in bacterial culture media remains largely unexplored. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive or generalizable predictive model exists for forecasting pH variations across diverse bacterial strains and culture conditions. A rare exception is the phenomenological model introduced by Ratzke and Gore, which utilized two differential equations to simulate microbial growth and environmental pH modification11. Their model captures basic pH-induced feedback loops within mono- and co-culture systems and demonstrated emergent behaviors such as ecological suicide, Allee effects, and bistability. However, the model remains qualitative and limited to synthetic examples with fixed parameters, without being trained or validated against experimental data at a large scale. In contrast, the present study offers a data-driven framework based on advanced machine learning models to quantitatively predict pH trajectories based on real experimental datasets. Therefore, our approach represents a novel and scalable contribution to microbial pH modeling.

Overview of machine learning and thermodynamic techniques

Machine learning methods

Artificial intelligence techniques have emerged as vital tools in biotechnological research for predictive modeling, particularly in scenarios involving complex variable interactions such as pH variation forecasting. In this study, seven advanced artificial intelligence algorithms including 1D-CNN, ANN, DT, RF, AdaBoost, EL, and LSSVM are utilized to model the pH dynamics of culture media influenced by bacterial growth. These methods excel at detecting intricate, non-linear patterns within experimental datasets, offering a robust and efficient alternative to conventional experimental approaches due to their computational efficiency, adaptability, and high predictive precision.

Artificial neural Network-based models

Convolutional neural networks (1D-CNNs)

1D-CNNs are specialized deep learning architectures designed to handle structured data, such as images. They employ convolutional layers to detect localized features like edges, patterns, and forms within the input, enabling robust identification of intricate structures and relationships12. Mathematically, the convolution operation in a 1D-CNN is expressed as Eq. (1):

Here, f denotes the input image or feature map, g represents the convolutional kernel, and (x, y) indicate the spatial coordinates of the output feature map.

1D-CNNs are composed of multiple convolutional layers, which progressively extract more complex and abstract features13. A key advantage of 1D-CNNs is their ability to process high-dimensional datasets, making them well-suited for tasks such as image classification and object recognition. Pooling layers are often incorporated to reduce data dimensionality and prevent overfitting. Due to their powerful capabilities, 1D-CNNs have revolutionized computer vision. By stacking several convolutional layers, 1D-CNNs can learn hierarchical feature representations, capturing critical details at varying levels of abstraction. This multi-layered approach enables 1D-CNNs to effectively interpret complex visual data, driving significant advancements in numerous computer vision applications14. 1D-CNN was used because of its strong ability to model spatial patterns and hierarchical representations, which are useful when capturing complex, nonlinear interactions among input features. Its use in a regression context for biological datasets is relatively novel.

Artificial neural network (ANN)

In this research, ANN used is a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) architecture, which consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Typically, an ANN comprises an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, each composed of interconnected artificial neurons15,16. Within the ANN algorithm, input data is first introduced to the input layer, where neurons in each subsequent hidden layer process the outputs from the preceding layer, generating new outputs. This layer-by-layer data transformation persists until the information reaches the output layer, yielding the final prediction or outcome17. The result of a neuron in the ANN is mathematically represented as Eq. (2):

where n is the number of input features, wi and xi are the i-th weight and input value respectively, and b is the bias term.

The training process of an ANN involves optimizing the weights and biases to minimize the error between predicted and actual outputs, typically using a backpropagation algorithm combined with gradient descent18. During backpropagation, the error is propagated backward from the output layer to the input layer, adjusting the weights and biases based on the calculated gradients. This iterative process continues until the model converges to an acceptable error level or a predefined number of epochs is reached. Activation functions, such as sigmoid, Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) are applied to the neurons’ outputs to introduce non-linearity, enabling the ANN to solve complex, non-linear problems effectively19. The flexibility and robustness of ANNs make them suitable for applications ranging from image recognition to natural language processing, although they may require careful tuning and sufficient computational resources to achieve optimal performance. ANN was chosen due to its flexibility in capturing nonlinear relationships in multivariate biological data, especially when the input variables interact in complex ways. It serves as a baseline deep learning model for comparison.

Tree-based models

Decision tree (DT)

DT are a flexible supervised learning approach suitable for both classification and regression tasks, producing interpretable models through iterative binary partitioning. This method relies on impurity measures, such as the Gini index, information gain, or variance reduction, to determine optimal splits at each node. Internal nodes define decision rules based on features, while leaf nodes provide the final predictions. This process is illustrated in Eqs. (3) and (4) below:

The splitting criteria assess feature significance by analyzing probabilistic class distributions. This structured breakdown facilitates clear visualization of decision pathways and supports both numerical and categorical data with minimal preprocessing20,21.

Valued for their transparency and ability to capture nonlinear patterns, DT require careful regularization to avoid overfitting, employing techniques such as pruning, restricting tree depth, or integration with ensemble methods. Their key strengths built-in feature selection, resilience to outliers, and minimal data assumptions make them especially useful in regulated domains like medical diagnostics and financial risk assessment22,23. DT was applied for its interpretability and fast training. It provides insights into decision rules and feature importance, offering a transparent model that serves as a reference for more complex tree-based methods.

Random forest (RF)

RF method is a powerful supervised learning method widely applied in regression and classification tasks. It operates by constructing a multitude of decision trees, each trained on randomly sampled subsets of the data and features through techniques like bagging (bootstrap aggregation) and random feature selection. This approach fosters diversity by training each tree on a unique random subset, thereby improving predictive accuracy and generalization. For regression jobs, the algorithm computes the average of all tree estimations, while for classification, it selects the predominant class through majority voting. The ensemble of trees mitigates the overfitting often associated with single DT and maintains strong performance even with noisy data or imbalanced classes. Owing to its reliability, versatility, and consistently high performance, RF is extensively used in fields such as medical diagnostics, financial modeling, and bioinformatics24,25. The regression output is typically derived as the average of individual tree predictions, formulated as Eq. (5):

A significant strength of RF lies in its capacity to assess the relative importance of features, providing critical insights into the effect of every variable on the model’s forecasts. Compared to more intricate models like deep neural networks, RF requires less extensive hyperparameter optimization while delivering robust performance on large, high-dimensional datasets. However, its predictive accuracy may occasionally fall short of advanced methods like gradient boosting, and it can demand substantial computational resources for very large datasets. Nevertheless, RF remains a cornerstone of machine learning due to its combination of interpretability, resilience, and dependable performance, making it a preferred choice for a wide range of analytical applications26,27. RF was used to reduce overfitting compared to a single decision tree. By aggregating multiple trees, it enhances stability and is effective for datasets with noise or variable interactions.

Adaptive boosting (AdaBoost)

AdaBoost is a prominent ensemble learning technique that improves predictive accuracy by iteratively training a sequence of weak classifiers, typically basic decision stumps. At each step, the algorithm prioritizes data points misclassified in previous iterations, guiding subsequent learners to focus on these challenging cases. Each weak learner is assigned a weight reflecting its predictive performance, and the final prediction is derived as a weighted combination of all learners’ outputs. This iterative approach enables AdaBoost to perform exceptionally well in binary classification and regression tasks with complex or noisy datasets28,29. The process for updating the weight of each training sample is expressed as Eq. (6):

Here, wi(t) represents the weight of the i-th sample in the t-th iteration, αt denotes the weight or influence of the weak classifier ht at that stage, yi is the true label of the i-th data point, and ht(xi) indicates the prediction made by the weak learner ht for that instance. The parameter αt, which quantifies the contribution of the weak learner to the final model, is computed as Eq. (7):

In this formula, Errort signifies the weighted classification error of the weak learner ht during the t-th iteration. In this study, AdaBoost was employed to boost prediction precision by sequentially training multiple weak models, with increased focus on difficult-to-predict instances. Cross-validation was used to optimize the learning rate and the number of boosting iterations, ensuring a balance between reducing bias and preventing overfitting for robust generalization. This method was selected for its effectiveness in handling diverse datasets and enhancing the performance of simple classifiers. However, its sensitivity to noisy data and outliers necessitated thorough preprocessing to mitigate these challenges30,31. AdaBoost focuses on correcting errors by emphasizing misclassified points, making it valuable for capturing difficult patterns in pH behavior. Its iterative learning strategy improves accuracy over weak base learners.

Ensemble/Hybrid models

Ensemble Learning (EL) is not a single model but a general strategy that combines multiple base learners to improve predictive performance. In this study, a heterogeneous ensemble model was developed by integrating three distinct algorithms: Support Vector Machine (SVM) with an RBF kernel, Decision Tree (DT), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) with Euclidean distance. The final prediction was made using a weighted voting mechanism based on the individual performance of each base learner. This EL model differs from Random Forest (RF), which is a homogeneous ensemble method composed exclusively of decision trees trained on random subsets of data and features. The inclusion of diverse model types in EL allows leveraging their complementary strengths, offering improved generalization compared to single-model or single-family ensembles like RF. These approaches are highly effective in reducing overfitting and enhancing generalization, making them well-suited for complex, diverse datasets, such as those employed in modeling pH variations in culture media32,33. For instance, in a weighted voting framework, the final prediction ŷ is determined as Eq. (8):

Here, T represents the total number of models in the ensemble, wt denotes the weight assigned to the t-th model, ht(x) signifies the prediction of the t-th model for input x, I(⋅) is an indicator function returning 1 if the condition holds and 0 otherwise, and c indicates the possible class labels. A custom ensemble was created by combining heterogeneous models (SVM, DT, KNN) to leverage complementary strengths and improve generalization. This hybrid ensemble provides robustness in prediction across varied bacterial and media conditions.

Kernel-based model

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a supervised learning method commonly applied to both classification and regression problems. Its fundamental principle is to determine the hyperplane that best separates data points from different classes while maximizing the margin between them. For nonlinear problems, SVM employs kernel functions to transform data into higher-dimensional space, allowing linear separation. Despite its robustness and accuracy, standard SVM involves solving a quadratic programming problem, which can be computationally intensive for large datasets. Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LSSVM) modifies the standard SVM by replacing the quadratic optimization with a least squares cost function, transforming the problem into a system of linear equations.

Unlike traditional SVM, which relies on quadratic programming, LSSVM utilizes a least squares loss function, simplifying the optimization process into solving a system of linear equations. This reformulation substantially lowers computational demands, making LSSVM highly effective for handling large datasets34.

The goal of LSSVM is to identify a decision function that reduces prediction errors while preserving the model’s ability to generalize. The prediction function in LSSVM is typically formulated as Eq. (9):

where w represents the weight vector, ϕ(x) denotes the transformation of input data x into a higher-dimensional space via a kernel function, and b is the bias term. Frequently employed kernel functions, such as radial basis function (RBF), polynomial, and linear kernels, enable LSSVM to model non-linear patterns in the input data35.

In this research, LSSVM was selected for its robust performance in managing complex, high-dimensional datasets with minimal computational overhead. Hyperparameters, including the regularization parameter and kernel-specific settings, were fine-tuned through cross-validation to optimize predictive accuracy. Additionally, feature scaling was implemented before training to ensure equitable contributions of all features to the kernel-based similarity computations. LSSVM was selected for its efficiency and effectiveness in modeling nonlinear relations with limited data. Its use of least squares formulation simplifies optimization and is computationally efficient.

Coupled simulated annealing (CSA) optimization algorithm

Simulated Annealing (SA) is a probabilistic optimization algorithm inspired by the annealing process in metallurgy, where a material is heated and then slowly cooled to remove defects and reach a stable state. In the context of optimization, Simulated Annealing (SA) replicates this behavior by randomly searching the solution space and occasionally accepting inferior solutions with a defined probability, allowing the algorithm to avoid becoming trapped in local minima. Over time, the algorithm reduces its “temperature” parameter, gradually focusing on more promising areas of the solution space. This makes SA particularly useful for solving complex, multimodal, and non-convex optimization problems. CSA algorithm represents an evolved version of the conventional Simulated Annealing (SA) technique. Unlike standard SA, which navigates the solution space through a single trajectory and employs probabilistic acceptance of suboptimal solutions to escape local minima, CSA advances this method by executing multiple concurrent search processes36,37. These processes are interconnected via a shared acceptance criterion, fostering solution diversity and markedly enhancing convergence speed and reliability. By incorporating this coupling mechanism, CSA reduces the chances of early convergence and boosts the probability of identifying the global optimum37,38.

The primary advantage of CSA lies in its effective balance of exploration and exploitation. Each independent search generates new potential solutions, but their acceptance is orchestrated globally through an entropy-driven control mechanism. This coordination maintains an optimal level of randomness or “temperature” throughout the optimization process. Consequently, CSA excels in tackling high-dimensional, intricate, and multimodal optimization challenges where conventional approaches may falter. Its applications extend to fields such as engineering design, machine learning hyperparameter optimization, and modeling complex systems39.

Data gathering and evaluation indices

Data collection description

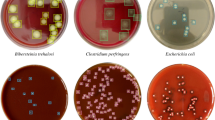

The dataset utilized for constructing the artificial intelligence models in this study was compiled from experimental investigations focused on assessing the pH variations in culture media influenced by bacterial growth across diverse conditions. A total of 379 experimental data points were gathered, incorporating critical input variables such as bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time (hours), and bacterial cell concentration (OD600). The bacterial strains examined include Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922, and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344, cultured in LB and M63 media. The bacterial strains examined include Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922, and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344, cultured in Luria Bertani (LB) and M63 media. The bacterial strains selected for this study including Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344 were chosen based on their relevance to microbiological and biotechnological research. E. coli ATCC 25,922 serves as a standard model organism frequently used in laboratory studies due to its well-characterized physiology. P. putida KT2440 is widely recognized for its metabolic versatility and its role in bioremediation and synthetic biology. P. pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344, on the other hand, is an alkaliphilic bacterium known for its ability to degrade cyanide under basic conditions. Together, these strains represent a broad spectrum of physiological traits and environmental adaptability, making them suitable candidates for evaluating pH variation under diverse growth conditions. This comprehensive dataset establishes a strong foundation for developing and evaluating predictive models capable of simulating pH dynamics under a variety of microbial and environmental conditions10. In order to introduce the bacterial strains in the developed models, one-hot encoding that can transform each category into a vector was used. It is essential since many algorithms cannot directly process categorical data. For this purpose, a vector in which all elements are 0 except for one position was used. This position was set to 1 showing the presence of that type of bacterial strain.

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the experimental systems analyzed in this study, summarizing their key characteristics and experimental parameters for modeling pH behavior. The dataset, encompassing 379 observations, covers initial pH values ranging from 6 to 9, time intervals from 0 to 68.27 h, OD600 between 0 and 1.7184, and system pH values spanning 4.59 to 9.03. This extensive dataset, capturing diverse bacterial strains, media types, and experimental conditions, provides a solid platform for building highly precise artificial intelligence models capable of accurately predicting pH variations across different microbial growth scenarios and environmental settings.

Model evaluation indices

To assess and compare the predictive capabilities of the developed models, a range of essential performance metrics were calculated for each modeling technique. The models evaluated in this study encompass artificial intelligence methods, including 1D-CNN, ANN, RF, DT, EL, AdaBoost, LSSVM. These algorithms were applied to predict the pH variations in culture media influenced by bacterial growth, using input variables such as bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time, and bacterial cell concentration (OD600). To measure the precision and reliability of each model across both training and testing phases, key evaluation metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R²), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE%) and root mean square error (RMSE), were determined40,41,42. These are defined in Eqs. (10)–(13):

Relative error percent:

Mean absolute percentage error:

Mean square error:

Determination coefficient:

In the given equations, the subscript ‘i’ represents the identifier for each specific points. The terms ‘pred’ and ‘exp’ represent estimated and experimentally observed pH values of the culture media, respectively43,44. The variable ‘N’ indicates the total number of data points used in this study, comprising 379 experimental measurements of pH variations influenced by bacterial growth in culture media45.

The models were developed using input variables including bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time, and bacterial cell concentration (OD600), with the pH of the culture media as the output variable. To ensure effective model training and reliable performance evaluation, the dataset was randomly split into training and testing subsets, with 80% of the data (303 points) allocated for training and the remaining 20% (76 points) reserved for testing.

To address the varying numerical scales of the input and output variables, a modified min-max normalization technique was implemented before model construction, scaling all features to a uniform range of [− 1, 1]. This preprocessing step improves model stability and convergence by reducing the influence of features with larger numerical values, thereby enhancing the predictive consistency of the artificial intelligence models. The normalization approach applied is outlined in Eq. (14):

In the given equation, xN signifies the normalized value, x denotes the original, unscaled data point, and Xmax and Xmin represent the maximum and minimum values within the dataset, respectively. By transforming the feature values to a standardized range of [− 1, 1], this preprocessing step ensures data consistency, thereby enhancing the accuracy and stability of the artificial intelligence models developed in this study.

In the normalization formula provided, xN indicates the normalized value, x corresponds to the raw, unnormalized data, and Xmax and Xmin refer to the highest and lowest values in the dataset, respectively. This customized normalization technique was applied to the 379 experimental measurements of pH variations in culture media influenced by bacterial growth. By scaling the feature values to the [− 1, 1] range, this preprocessing method fosters uniformity across the dataset, significantly improving the precision and reliability of the artificial intelligence models constructed in this research.

Results and analysis

Outlier detection

The leverage method is a diagnostic tool used to identify influential data points in regression analysis. It evaluates how far the values of a data point’s input variables deviate from the mean of all input values. High leverage points can exert strong influence on the model’s predictions. In combination with standardized residuals, leverage values are often used in Williams plots to detect outliers or influential observations. A data point is typically considered influential if its leverage value exceeds a specific threshold, and its standardized residual is large. The initial equation expresses the difference Di as follows (Eq. 15)34,40,46,47,48:

In this context, Di represents the residual for i-th point, calculated as the difference between the predicted pH value (XPred, i) and the experimentally observed pH (XExp, i) in the culture media affected by bacterial growth. This residual quantifies the prediction error for each data point within the dataset. The standardized residual (SDi) is defined by the subsequent Eq. (16):

The standardized residual (SDi) is obtained by dividing the raw residual (the difference between predicted and experimental values) by the standard deviation of all residuals. This normalization allows for consistent detection of outliers by comparing how far each point deviates from the model’s general trend. Figure 2 illustrates the identification of outliers in the pH dataset for bacterial growth using the leverage method, presented via a Williams plot. The denominator normalizes the residual by the standard deviation of residuals, adjusted by the leverage hi, which measures the impact of every data point on the model’s alignment. The leverage threshold h∗ is calculated as h∗=3(m + 1)/N, where m is the number of input features (5 in this study: bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time, and bacterial cell concentration) and N is the dataset size. For this dataset, h∗=3(5 + 1)/379 = 0.0475. Data points with hi> h∗ are deemed high-leverage points, suggesting potential influence, while standardized residuals exceeding typical thresholds (commonly ∣SDi∣>3) are flagged as outliers. This analysis confirms the dataset’s suitability for pH prediction modeling and provides valuable insights into the dynamics of bacterial growth and pH interactions in culture media.

Hyperparameters optimization and models evaluation

To optimize the performance of each machine learning model, key hyperparameters were tuned using trial-and-error methods guided by performance metrics such as R² and MSE. While detailed optimization procedures were initially illustrated through individual figures for each model, these plots and their corresponding analyses have been moved to the Supporting Material (Figures S1–S4) to enhance clarity and reduce visual overload in the main text. Hyperparameters for all models were meticulously optimized using CSA algorithm to ensure peak performance and avoid overfitting. A summary of the optimal hyperparameter configurations for each model is presented in Table 2, which was found to be sufficient for conveying the necessary results without excessive redundancy. This adjustment was made in accordance with reviewer recommendations, ensuring that the main body of the manuscript remains concise and reader-friendly.

Table 3 offers a detailed overview of the performance metrics for seven artificial intelligence models, including DT, RF, EL, AdaBoost, ANN, 1D-CNN, and LSSVM, developed to predict pH variations in culture media influenced by bacterial growth. The assessment utilized three primary metrics: R², RMSE, and MAPE%, computed for the training (303 points), testing (76 points), and total datasets.

The results in Table 3 establish a distinct performance hierarchy among the models. The 1D-CNN demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy, achieving an R² of 0.998301691 for the total dataset, with the lowest RMSE (0.051935903) and MAPE% (0.370554549), showcasing its exceptional ability to model the complex relationships among input features, including bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH (6–9), time (0–68.27 h), and bacterial cell concentration (0–1.7184 OD600). The EL model followed closely, exhibiting strong performance with an R² of 0.998222719 and low error rates, while the ANN and LSSVM models also showed robust predictive capabilities, maintaining R² values above 0.997 and MAPE% below 0.6. Conversely, the RF and AdaBoost models displayed slightly lower accuracy compared to 1D-CNN and EL but remained within acceptable predictive ranges.

Figure 3 enhances the insights from Table 3 by providing a visual comparison of model performance during the testing phase, likely through bar charts comparing R², RMSE, and MAPE% values across all models. The figure clearly highlights 1D-CNN’s superior predictive precision, with the closest alignment between predicted and experimental pH values for the 76 test points. It also reveals relatively higher error margins for models like DT and AdaBoost compared to 1D-CNN and EL, underscoring the advantages of deep learning and ensemble methods in addressing complex pH dynamics.

Collectively, Table 3; Fig. 3 emphasize the efficacy of advanced artificial intelligence techniques, particularly 1D-CNN, in precisely predicting pH variations in culture media due to bacterial growth. These findings highlight the potential of CSA optimized computational models as reliable, efficient alternatives to conventional experimental methods, providing valuable tools for optimizing biotechnological processes where pH control is critical. Moreover, a standard ordinary least squares linear regression (LR) model was utilized using the same training and test subsets of the ML models. The performance metrics (R², RMSE, MAPE) of the LR model were then compared with those of the ML models and the results are shown in Table 3; Fig. 3. The results demonstrated that while the LR model achieved reasonably good performance, the ML models still outperformed it consistently, particularly in capturing nonlinear patterns and interactions between input features.

Figure 4 further complements these findings by illustrating the distribution of absolute relative errors for all machine learning models. The histograms show that most predictions for 1D-CNN and EL models are concentrated in the lowest error bins, confirming their superior accuracy and consistency across the dataset. In contrast, models such as DT and AdaBoost exhibit broader error distributions, reflecting slightly higher prediction variability. The MLP-ANN, LSSVM, and RF models fall between these extremes, maintaining moderate error concentrations. This comparative view highlights the advantages of deep learning and ensemble approaches in minimizing prediction errors and reinforces the performance hierarchy established by the quantitative metrics in Table 3.

Figure 5 present crossplots comparing predicted versus experimental pH values for culture media influenced by bacterial growth, employing seven distinct artificial intelligence models. These models include 1D-CNN, EL, AdaBoost, DT, RF, ANN, and LSSVM. The analysis is based on a 379-point experimental dataset, split into 303 data points for training and 76 for testing. These crossplots serve as vital visual tools for assessing the predictive performance of each model, with optimal performance indicated by data points tightly clustered along the 45-degree line.

The dataset encompasses three bacterial strains including Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922 and cultured in LB and M63 media, with initial pH values ranging from 6 to 9, time intervals from 0 to 68.27 h, OD600 from 0 to 1.7184, and system pH values spanning 4.59 to 9.03. Collectively, Fig. 5 provides a comprehensive visual assessment of the models’ predictive capabilities, with the 1D-CNN model exhibiting exceptional accuracy, demonstrated by the tight alignment of predicted and experimental pH values across all bacterial and media systems. EL and ANN also show robust performance, while models such as DT and AdaBoost display relatively wider scatter, suggesting slightly lower precision.

These crossplots validate the reliability of the 379-point dataset and the effectiveness of the data normalization technique applied, which reduced disparities in input scales and supported stable, accurate model training. Overall, the figures underscore the 1D-CNN model’s superior capacity to capture complex, non-linear relationships between key input features and pH behavior, highlighting its potential for enhancing applications such as microbial process optimization, bioreactor design, and biotechnological advancements.

Figure 6 illustrates the relative error percentages during the training and testing phases for seven artificial intelligence models developed to predict pH variations in culture media influenced by bacterial growth. Data points closer to the y = 0 line indicate superior predictive accuracy across the 379-point dataset (303 training points and 76 testing points). Among the models, 1D-CNN exhibits exceptional performance, with the tightest error distribution (MAPE% = 0.370554549, R² = 0.998301691), followed by EL (MAPE% = 0.37966203) and ANN (MAPE% = 0.502705344). In contrast, DT (MAPE% = 0.767710648) and AdaBoost models show wider error ranges. This visual analysis underscores 1D-CNN’s remarkable ability to precisely capture the complex effects of bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH (6–9), time (0–68.27 h), and bacterial cell concentration (0–1.7184 OD600) on pH behavior, affirming its effectiveness for applications such as microbial process optimization, bioreactor design, and biotechnological advancements.

Sensitivity analysis

This section of the study explores the influence of key input variables include bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time, and bacterial cell concentration (OD600) on the pH variations in culture media due to bacterial growth, while evaluating the relative significance of each factor. The importance of these input features is quantified through correlation coefficients, offering insights into their contributions to the pH prediction models developed using 379 experimental data points49.

In this analysis, the Monte Carlo simulation approach, appreciated for its simplicity and clarity, is utilized to assess the relative impact of the input variables on the pH behavior of culture media. It is important to clarify that Monte Carlo simulation in this study is not used to directly predict pH values, but rather to assess the sensitivity of input variables within the trained machine learning models. While Monte Carlo methods can be employed in traditional simulation contexts, they require prior knowledge of system equations and are computationally intensive when applied directly to complex biological processes. In contrast, machine learning models offer a data-driven alternative that can learn from experimental data without requiring explicit mechanistic formulations, providing faster and often more accurate predictions. Therefore, the Monte Carlo method was used to explore the influence of input variables on the output of ML models, not to simulate pH itself. The ML models remain central to the prediction framework, while Monte Carlo simulation supports interpretability and sensitivity analysis. The best model, i.e. 1-D CNN model was coupled with the Monte-Carlo algorithm for determining the most sensitive factors.

Monte Carlo simulation approach excels in managing uncertainties by systematically sampling a wide range of input values, allowing direct evaluation of output variability without dependence on proxy modeling. Within this framework, the model incorporates multiple input parameters, defined as Eq. (17)49:

The range and distribution properties of each input variable () are established and used to create a comprehensive sampling set as Eq. (18):

Here, k represents the total number of generated samples, and n denotes the number of input features considered. Various sampling techniques, such as random sampling, importance sampling, and Latin hypercube sampling (LHS), may be applied at this stage to construct the input dataset. The model is then executed for each set of sampled inputs to produce the corresponding output results as Eq. (19):

In this context, k indicates the number of samples generated, and n represents the number of input variables. Multiple sampling strategies, including random sampling, importance sampling, and Latin hypercube sampling (LHS), can be employed during this phase. The model is applied to each set of sampled input variables to compute the corresponding output results, as defined in Eqs. (20) and (21):

Here, V and E denote the variance and expected value, respectively. Sensitivity analysis is then performed based on the input-to-output relationship described in Eq. (22). Among the various methods for visualizing this relationship, scatterplot generation is regarded as one of the most straightforward and effective techniques:

Figure 7 presents a detailed sensitivity analysis assessing the relative influence of bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH, time, and bacterial cell concentration on the pH behavior of culture media, employing a Monte Carlo simulation integrated with the artificial intelligence models developed in this study. The Monte Carlo method, recognized for its robustness in addressing uncertainties, systematically samples variations in the input parameters to evaluate their impact on pH predictions. The findings are displayed using a correlation matrix or comparable visualization, highlighting both the magnitude and orientation of the associations between each input variable and the resulting pH response.

The analysis identifies bacterial cell concentration as the most influential factor, with a correlation coefficient of 4.9825, underscoring its pivotal role in driving pH variations across the studied systems. Time follows closely, with a correlation coefficient of 4.8312, indicating that the duration of bacterial growth significantly affects pH dynamics. The type of culture medium, with a correlation coefficient of 3.7482, also exerts a substantial influence, suggesting that the media composition plays a critical role in pH changes. Bacterial type and initial pH, with correlation coefficients of 2.4972 and 2.2483, respectively, demonstrate comparatively lesser but still notable impacts.

Based on the analysis of 379 experimental data points, bacterial cell concentration and incubation time were identified as the most influential variables affecting pH changes in the culture media. Other features exhibited weaker correlations, suggesting that microbial metabolism and growth phase primarily drive acidification or alkalization dynamics. The use of Monte Carlo simulation enhances the reliability of this analysis by accounting for input uncertainties, providing a robust basis for understanding the underlying mechanisms. Figure 7 serves as a valuable resource for researchers, offering practical guidance for optimizing microbial processes where pH control is critical for biotechnological applications.

Temporal analysis of bacterial growth and pH dynamics in LB and M63 media using machine learning modeling

In the context of predictive modeling, a critical aspect is the model’s ability to accurately forecast not only individual data points but also the overall trend of the output variable. In this study, the top-performing model, 1D-CNN, was employed to predict the trend of pH variations in the growth medium during the bacterial growth process for each bacterial strain. The results demonstrate that the developed 1D-CNN model effectively captures this trend, reflecting its capability to simulate the dynamic pH behavior. Moreover, this approach serves as a form of process simulation through the application of intelligent models, providing a reliable tool for understanding and predicting microbial growth dynamics.

Figure 8 presents a comprehensive overview of the 1D-CNN model’s predictive performance across six distinct bacterial strain–medium combinations. In each subplot (8a–8f), the red line represents the predicted pH trend, the green dots indicate experimentally measured pH values, and the blue line denotes bacterial growth over time (OD600). These experiments reflect different environmental settings and initial pH conditions, demonstrating the model’s ability to generalize across multiple growth scenarios.

Figure 8a shows the results for Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922 cultivated in LB medium with an initial pH of 6. The bacterial growth exhibited a classical sigmoidal pattern, rising from 0.0028 to 1.46 OD600 over ~ 39 h. The predicted pH increased from 6.0 to 8.76, closely aligning with experimental data (6.15–8.69), confirming the model’s high accuracy in alkaline pH forecasting under nutrient-rich conditions. Figure 8b corresponds to Pseudomonas putida KT2440 grown in LB medium (initial pH 6). Growth peaked at 1.62 OD600 in ~ 42 h, and the predicted pH ranged from 6.0 to 8.76. The predictions tightly followed the experimental range (6.25–8.75), demonstrating the model’s robustness in capturing pH elevation due to metabolic activity.

Figure 8c illustrates the growth of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344 in LB medium with an initial pH of 7.5. Here, bacterial growth progressed steadily from 0 to 1.24 OD600 over ~ 57 h. The model accurately predicted a gradual pH increase from 7.43 to 8.55, matching experimental data (7.44–8.55), validating its effectiveness for neutral–alkaline starting conditions. Figure 8d displays results for E. coli ATCC 25,922 cultured in M63 minimal medium starting at pH 7. The bacterial growth reached 1.35 OD600 after ~ 46 h. In contrast to the LB medium results, pH decreased over time, and the model captured this acidification trend, predicting a decline from 7.09 to 6.46, consistent with the measured range (7.05–6.49). This illustrates the 1D-CNN model’s capability to handle both increasing and decreasing pH dynamics. Figure 8e reports the behavior of P. putida KT2440 in M63 medium with an initial pH of 8. The growth curve showed a peak at 1.42 OD600 after ~ 48 h. The model predicted a modest decline in pH from 7.82 to 7.42, accurately reproducing the experimental values (7.79–7.43), suggesting it can model moderate pH shifts under nutrient-limited conditions. Figure 8f shows the dynamics for P. pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344 in M63 medium with an initial pH of 9. Bacterial growth increased to 1.38 OD600 over ~ 68 h. The model forecasted a steady decrease in pH from 8.11 to 7.52, aligning well with the measured pH trend (8.11–7.56), reinforcing its performance in alkaline environments.

Overall, the 1D-CNN model demonstrated consistent and accurate prediction across a wide spectrum of microbial growth conditions, pH trends (both rising and falling), and media compositions. These results validate the suitability of 1D-CNN for modeling pH dynamics in microbiological systems and reinforce its potential as a non-invasive, data-driven tool for predictive bioprocess monitoring and optimization.

From a technological perspective, the artificial intelligence framework developed in this study, validated through sensitivity analyses and error distribution assessments, demonstrates promising capabilities for data-driven modeling of microbiological pH variations. While not claiming to establish a universal benchmark, the approach provides a practical example of how machine learning can capture key patterns in moderately complex systems using available experimental data. This work highlights potential applications in biotechnology and microbial process optimization, but further research with larger and more diverse datasets will be required to fully generalize these findings to broader and more intricate biological contexts.

Moreover, the computational efficiency of this methodology supports more sustainable research practices by decreasing reliance on extensive experimental efforts, aligning with modern goals of operational efficiency and environmental responsibility in scientific and industrial settings. However, there are some limitations that should be acknowledged. Needing external validation and independent datasets, lack of interpretability for some of high-performing ML models like ANN and RF and the black box nature of the models, and high computational complexity of some models such as ANN and EL are the main limitations of the current study that need to be addressed in future works.

Conclusions

This research successfully developed and validated an extensive array of predictive models using advanced artificial intelligence techniques, including 1D-CNN, EL, AdaBoost, DT, RF, ANN, and LSSVM, to forecast pH variations in culture media influenced by bacterial growth. A comprehensive experimental dataset comprising 379 points was employed, incorporating critical input variables such as bacterial type, culture medium type, initial pH (6–9), time (0–68.27 h), and bacterial cell concentration (0–1.7184 OD600). The primary objective was to create precise predictive models for pH dynamics under diverse microbial conditions. Model performance was significantly improved through hyperparameter optimization using the CSA algorithm, ensuring exceptional predictive accuracy. Thorough evaluations, including correlation analysis, crossplots, and relative error assessments, identified 1D-CNN as the top-performing model, achieving an R² of 0.998301691, RMSE of 0.051935903, and MAPE% of 0.370554549, showcasing its superior ability to capture complex pH behavior. Sensitivity analysis via Monte Carlo simulations indicated that bacterial cell concentration had the greatest impact (correlation coefficient = 4.9825), followed by time (4.8312), culture medium type (3.7482), bacterial type (2.4972), and initial pH (2.2483), providing valuable insights into the key factors driving pH variations. These results underscore the significant benefits of employing artificial intelligence methods over conventional experimental approaches, offering a highly accurate, efficient, and cost-effective framework for predicting microbiological properties. This approach holds substantial potential for biotechnological applications, enabling the optimization of microbial processes and bioreactor design. Future studies could further refine model accuracy by incorporating additional biological or environmental factors, such as nutrient composition or oxygen levels, to broaden applicability across diverse microbial systems.

Data availability

All data used during this study are included in the published article and the provided supplementary file. All the codes and calculation files are also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aoi, W. & Marunaka, Y. Importance of pH homeostasis in metabolic health and diseases: crucial role of membrane proton transport. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014 (1), 598986 (2014).

Batool, Z. et al. Regulation of physiological pH and consumption of potential food ingredients for maintaining homeostasis and metabolic function: an overview. Food Reviews Int. 39 (8), 5087–5103 (2023).

Matthew, J. B. et al. pH-dependent processes in protein. Crit. Reviews Biochem. 18 (2), 91–197 (1985).

Jin, Q. & Bethke, C. M. The thermodynamics and kinetics of microbial metabolism. Am. J. Sci. 307 (4), 643–677 (2007).

Bibby, S. R. S. et al. Metabolism of the intervertebral disc: effects of low levels of oxygen, glucose, and pH on rates of energy metabolism of bovine nucleus pulposus cells. Spine 30 (5), 487–496 (2005).

Casey, J. R., Grinstein, S. & Orlowski, J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11 (1), 50–61 (2010).

Krulwich, T. A., Sachs, G. & Padan, E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9 (5), 330–343 (2011).

Ratzke, C. & Gore, J. Modifying and reacting to the environmental pH drives bacterial interactions. BioRxiv, : p. 136838. (2017).

Nogales, J. et al. Expanding the computable reactome in Pseudomonas putida reveals metabolic cycles providing robustness. BioRxiv, : p. 139121. (2017).

Sánchez-Clemente, R. et al. Study of pH Changes in Media during Bacterial Growth of Several Environmental Strains. MDPI. (2018)

Ratzke, C. & Gore, J. Modifying and reacting to the environmental pH can drive bacterial interactions. PLoS Biol. 16 (3), e2004248 (2018).

Raja Sarobin, M. & Panjanathan, R. V. and Diabetic retinopathy classification using CNN and hybrid deep convolutional neural networks. Symmetry, 14(9): p. 1932. (2022).

Giusti, A. et al. Fast Image Scanning with Deep max-pooling Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE. (2013).

Yang, K. et al. Multi-criteria spare parts classification using the deep convolutional neural network method. Appl. Sci. 11 (15), 7088 (2021).

Valles, J. Application of a Multilayer Perceptron Artificial Neural Network (MLP-ANN) in Hydrological Forecasting in El Salvadorp. 213–239 (Machine Learning and Optimization for Water Resources, 2024).

Al-Mejibli, I. S., Alwan, J. K. & Abd, D. H. The effect of gamma value on support vector machine performance with different kernels. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 10 (5), 5497–5506 (2020).

Paluang, P., Thavorntam, W. & Phairuang, W. Application of multilayer perceptron artificial neural network (MLP-ANN) algorithm for PM2. 5 mass concentration Estimation during open biomass burning episodes in Thailand.International Journal of Geoinformatics (2024).

Ighalo, J. O., Igwegbe, C. A. & Adeniyi, A. G. Multi-layer perceptron artificial neural network (MLP-ANN) prediction of biomass higher heating value (HHV) using combined biomass proximate and ultimate analysis data. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8 (3), 3177–3191 (2022).

Pattanayak, S. et al. Application of MLP-ANN models for estimating the higher heating value of bamboo biomass. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 11, 2499–2508 (2021).

De Ville, B. Decision trees. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Stat. 5 (6), 448–455 (2013).

Suthaharan, S. & Suthaharan, S. Decision tree learning. Machine learning models and algorithms for big data classification: thinking with examples for effective learning, : pp. 237–269. (2016).

Kingsford, C. & Salzberg, S. L. What are decision trees? Nat. Biotechnol. 26 (9), 1011–1013 (2008).

Nowozin, S. et al. Decision tree fields. in 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision. IEEE. (2011).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Everingham, Y. et al. Accurate prediction of sugarcane yield using a random forest algorithm. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36, 1–9 (2016).

Hapfelmeier, A. & Ulm, K. A new variable selection approach using random forests. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 60, 50–69 (2013).

Genuer, R., Poggi, J. M. & Tuleau-Malot, C. VSURF: an R package for variable selection using random forests. R J. 7 (2), 19–33 (2015).

Margineantu, D. D. & Dietterich, T. G. Pruning Adaptive Boosting. In ICML (Citeseer, 1997).

Zheng, Z. & Yang, Y. Adaptive boosting for domain adaptation: toward robust predictions in scene segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 5371–5382 (2022).

Ferreira, A. J. & Figueiredo, M. A. Boosting algorithms: A review of methods, theory, and applications. Ensemble machine learning: Methods and applications, : pp. 35–85. (2012).

Lazarevic, A. & Obradovic, Z. Adaptive boosting techniques in heterogeneous and Spatial databases. Intell. Data Anal. 5 (4), 285–308 (2001).

Dong, X. et al. A survey on ensemble learning. Front. Comput. Sci. 14, 241–258 (2020).

DietterichT.G. Ensemble learning. Handb. Brain Theory Neural Networks. 2 (1), 110–125 (2002).

Bemani, A. et al. Estimation of adsorption capacity of CO2, CH4, and their binary mixtures in Quidam shale using LSSVM: application in CO2 enhanced shale gas recovery and CO2 storage. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 76, 103204 (2020).

Songolzadeh, R., Shahbazi, K. & Madani, M. Modeling n-alkane solubility in supercritical CO 2 via intelligent methods. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. 11, 279–287 (2021).

Gonçalves-e-Silva, K. & Aloise, D. Xavier-de-Souza, Parallel synchronous and asynchronous coupled simulated annealing. J. Supercomputing. 74, 2841–2869 (2018).

Yang, S. et al. A coupled simulated annealing and particle swarm optimization reliability-based design optimization strategy under hybrid uncertainties. Mathematics 11 (23), 4790 (2023).

Xavier-de-Souza, S. et al. Coupled simulated annealing. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics Part. B (Cybernetics). 40 (2), 320–335 (2009).

Suykens, J. A. K., Yalçin, M. E. & Vandewalle, J. Coupled Chaotic Simulated Annealing Processes. IEEE. (2003).

Bemani, A., Madani, M. & Kazemi, A. Machine learning-based Estimation of nano-lubricants viscosity in different operating conditions. Fuel 352, 129102 (2023).

Madani, M. et al. Modeling of CO2-brine interfacial tension: application to enhanced oil recovery. Pet. Sci. Technol. 35 (23), 2179–2186 (2017).

Daryasafar, A. et al. Connectionist approaches for solubility prediction of n-alkanes in supercritical carbon dioxide. Neural Comput. Appl. 29, 295–305 (2018).

Yuan, H. et al. Microfluidic-assisted caenorhabditis elegans sorting: current status and future prospects. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 4, 0011 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Dual recombinase polymerase amplification system combined with lateral flow immunoassay for simultaneous detection of Staphylococcus aureus and vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 255, 116621 (2025).

Izadmehr, M. et al. An exact analytical model for fluid flow through finite rock matrix block with special saturation function. J. Hydrol. 577, 123905 (2019).

Bassir, S. M. & Madani, M. A new model for predicting asphaltene precipitation of diluted crude oil by implementing LSSVM-CSA algorithm. Pet. Sci. Technol. 37 (22), 2252–2259 (2019).

Abbasi, P., Aghdam, S. K. & Madani, M. Modeling subcritical multi-phase flow through surface chokes with new production parameters. Flow Meas. Instrum. 89, 102293 (2023).

Madani, M., Moraveji, M. K. & Sharifi, M. Modeling apparent viscosity of waxy crude oils doped with polymeric wax inhibitors. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 196, 108076 (2021).

Madani, M. & Alipour, M. Gas-oil gravity drainage mechanism in fractured oil reservoirs: surrogate model development and sensitivity analysis. Comput. GeoSci. 26 (5), 1323–1343 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support provided by Zarqa University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammad, S.I., Owida, H.A., Vasudevan, A. et al. Accurate modeling and simulation of the effect of bacterial growth on the pH of culture media using artificial intelligence approaches. Sci Rep 15, 30569 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16150-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16150-x