Abstract

Digital image steganography is the art and science of hiding secret information in an innocent looking cover image to covertly exchange sensitive information in real-world scenarios. This paper presents a transform-domain steganographic method that leverages the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) and a skin-based masking mechanism to identify perceptually less sensitive regions for embedding while maintaining high imperceptibility and extraction accuracy. The proposed method extends our previous work using S-transform which is an integer-to-integer discrete wavelet transform (DWT). The hiding process starts with dividing the cover image into the basic color channels and applying DWT on each channel independently. The approximation coefficients of the DWT are then used to build a blocked skin-map. Only a pixel marked as “skin” in the blocked map will cause its corresponding approximation coefficients to be embedded with the bits of the secret message. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves competitive performance in terms of Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), outperforming several existing methods. Limitations and future directions, including robustness to geometric distortions and steganalysis detection, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

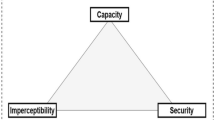

Steganography is a method of hiding secret messages within a cover medium, often encrypting them for added security. A general model for a steganographic channel is usually described in the context of the “prisoners’ problem” as shown in Fig. 1. In this scenario, two prisoners are communicating covertly, intending to exchange sensitive information while under surveillance. The problem arises from the need to secretly communicate an escape plan between Alice and Bob without alerting the warden. The challenge lies in finding a devising hiding technique that are imperceptible ensuring that the secret message remains undetected within the cover object1. Moreover, the prisoners must also consider the possibility of steganalysis, wherein the captors employ various statistical analysis and detection methods to identify hidden messages. Therefore, the prisoners must develop sophisticated steganographic algorithms to embed messages effectively while minimizing the likelihood of detection2.

In the digital age, the ubiquitous use of images for communication, sharing, and storage has made images the most used steganographic carrier. In addition, digital images provide a rich canvas for hiding data because they contain vast amounts of redundant information, allowing for subtle modifications without noticeably altering the image’s appearance nor detected using automated analysis tools. That’s why image steganography finds applications in various fields, including covert communication, digital watermarking, authentication, and copyright protection3. Its versatility makes it appealing for individuals and organizations with diverse needs.

Image steganography techniques usually embed a binary sequence of 0’s and 1’s in either the spatial domain or the transform domain of the cover image. Spatial techniques often involve replacing the least significant bits (LSBs) of pixels, while transform domain techniques alter transform elements, which are visually harder to detect. Various transform domains, such as discrete cosine transform (DCT), discrete wavelet transform (DWT), and contourlet transform, are used for steganography4. However, embedding messages into images can cause visual artifacts and alter image statistics, which can be detected by both human observation and steganalysis methods. Therefore, adaptive steganography, on the other hand, takes advantage of image features and information content to guide steganographic methods to minimize noticeable alterations in the embedded images along with maintaining statistical undetectability5,6.

Among the various approaches, the spatial domain LSB replacement method and the transform domain method utilizing wavelet transform are extensively applied in image steganography applications. These methods require fewer computations, offer substantial capacity, and exhibit robustness, thus garnering considerable attention in recent research endeavors. The authors of 2-bit LSB fusing7, for example, introduced an approach that enhances the conventional LSB replacement method through the integration of transform domain techniques. In their proposed method, they utilized the Haar DWT on the cover image and the pixel values of the message image are added the coefficients of the cover image. To ensure effective fusion, the dimensions of the message image must be equal to or smaller than half of those of the cover image which represents 25% of its size. Despite this high embedding capacity, the algorithm requires the original cover image as a key during extraction which is considered a disadvantage to any steganographic approach.

In8, on the other hand, the authors proposed a method of steganography in digital media using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and a 2D Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) at the 3rd level of decomposition. In their experiments, three 315 × 320 Gy images were used as test covers to hide exactly 302,454 bits of data. The proposed method worked well for information hiding against AWGN (additive white Gaussian noise) attack and fulfills the objective to achieve high robustness and high imperceptivity. Another approach combines the integer wavelet transform (IWT) with a chaotic map to improve the security of the proposed method IWT9. Their experiments used the NIST, DIEHARD and ENT tests suite to prove the randomness of the proposed chaotic map while maintaining an acceptable visual quality of embedded images.

In recent studies, various types of DWT have been utilized in image steganography, each with its own characteristics and advantages. The authors of FrRnWT10, for example, applied the Fractional Random Wavelet Transform (FrRnWT) on medical images to hide the medical records of the patients on moral grounds. They choose to apply the FrRnWT on the green color plane of the cover image and then split the average sub-band into equally sized non-overlapping blocks. The secret image, on the other hand, is encrypted using an Arnold scrambling algorithm. The number of scrambling iterations as well as the passkey should be agreed upon by both the sender and the receiver to further increase the security of the steganographic channel and prevent any unauthorized access of embedded information. The performance was analyzed for different embedding factors and the results showed that high values of the embedding factor can improve the invisibility of the hidden information.

To address the challenge of achieving a high embedding capacity while simultaneously preserving high perceptual embedding quality, the authors of QTAR11 presented an adaptive-region transform-domain embedding scheme using a curve-fitting methodology. The proposed scheme capitalizes on the observation that highly correlated images exhibit significant coefficients densely packed within the transform domain, thereby leaving ample space in areas of insignificant coefficients for embedding. Experimental findings illustrated an increased embedding capacity and an improved perceptual quality compared to other approaches.

Another adaptive steganographic technique was presented in12. The proposed algorithm used the Kirsch edge detector to guide the hiding process embedding and maximize payload by embedding more secret bits into edge pixels while fewer bits are embedded into non-edge pixels. The process starts with constructing a masked image from the cover image and then generating an edge image from the masked image. The cover image is then decomposed into triplets of pixels in which bits of the secret data are embedded to generate the stego-image. Simulation results showed that the Kirsch edge detector generates a greater number of edge pixels compared to traditional edge detectors, resulting in a superior performance in terms of both payload and image quality compared to conventional steganographic schemes.

In13, The authors proposed an adaptive image steganographic scheme designed to minimize distortion in the smooth areas of medical images. Their method divides the original JPEG image into several non-overlapping sub-images and preserves the correlation among inter-block adjacent DCT coefficients to maintain structural dependencies. The cost values of coefficients in each sub-image are dynamically updated based on changes in neighboring blocks during the embedding process. Although the method supports various types of hidden data, the authors evaluated its performance using randomly generated binary sequences embedded into JPEG images. Experimental results showed that the proposed approach slightly outperformed existing methods in terms of uniform embedding distortion (UED).

The authors in14, On the other hand, an Invertible Mosaic Image Hiding Network (InvMIHNet) was introduced to embed up to 16 secret images into a single cover image. The hiding process begins by feeding the mosaic of secret images into an Invertible Image Rescaling (IIR) module, which performs downscaling while preserving essential information. This is followed by the forward concealing process, which employs an Invertible Image Hiding (IIH) module consisting of a DWT/IDWT block and Invertible Neural Networks (INNs). These networks are trained to simultaneously minimize the restoration error between the original and recovered secret images and the visual difference between the cover and stego-images. When compared with two other high-capacity steganography methods, InvMIHNet demonstrated superior performance in both concealment and recovery quality.

In this paper, we present a high-capacity adaptive image steganographic technique. The method is an extension of the Enhanced Skin Block Map (ESBM) method published by the authors in15 and hence named hiESBM. The original research targeted skin areas in the cover image as a region of interest for hiding. The binary message is embedded into the integer Wavelet coefficients of the approximation sub-band of the cover image. Before embedding, the cover undergoes a conversion to the YCbCr color space where only the Y plane is utilized for hiding. Despite the enhanced message recoverability, the ESBM method offered a very limited hiding capacity which couldn’t exceed 0.007 bit-per-pixel in some cases. In hiESBM, however, we propose utilizing the full RGB color space in a pursuit of a higher payload. In addition, instead of a rule-based skin-detection technique, we explored using efficient machine learning methods to accomplish this task.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Sect. “The steganographic method” outlines the primary steps of the proposed steganographic method. In Sect. “Results”, we evaluate and analyze the method’s performance across various metrics, including imperceptibility, hiding capacity, and extraction accuracy. Section “Discussion” discusses the comparative performance of the proposed technique against other methods, including ESBM and its predecessor, SBM. Finally, Sect. “Conclusions” concludes the paper.”

The steganographic method

A steganographic channel consists of two main processes: the embedding process in which the sender hides the secret message in the cover image and the extraction process through which the receiver retrieves the embedded message from the stego-image. Figure 2 shows a general outline for the main steps we propose to be implemented as part of each process. Those in turn, will be described in details through the following subsections.

Skin detection

Skin detection is an important pre-processing step for several computer vision applications such as face recognition and gesture analysis. it can be defined as the process of classifying the pixels of a digital image into “skin” and “non-skin”16. Factors such as illumination, ethnicity, age, and background characteristics make skin detection a challenging task. Skin detection methods can be categorized into two main groups: rule-based methods and machine learning methods. The former set of techniques is simple, fast, and easy to implement and reuse. They usually depend on a perceptual uniform color space such as RGB17 or YCbCr18. On the other hand, recent approaches build and train a skin classifier model using advanced machine-learning techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and deep learning19. A more comprehensive survey on skin-detection method can be found in20.

The output of a skin detection algorithm is a binary map, where a value of one (white) means that the corresponding pixel is classified as “skin” otherwise it is “non-skin”, and it is set to zero (black) on the map. Figure 3 shows an example of skin map generated for a given image. Notice that some pixels were misclassified as skin regions. In fact, the precision of classification is an important performance indicator for skin-detection methods. It is usually computed using Eq. 1, where tp is the number of true positives and fp is the number of false positives.

In fact, the embedding process of the proposed technique will focus only on the skin pixels identified by this map. More specifically, three methods for skin detection will be utilized and contrasted: Cheddad17, SegNet19, and Deeplab21. Cheddad is a rule-based method that defines upper and lower thresholds that define the range of skin tone pixels. The method relies on a reduced color space that is derived from the difference between the grey-scale and the non-red encoded grayscale versions of the input image. SegNet, on the other hand, is a deep learning approach that was fine-tuned using the ECU dataset for image segmentation. The DeepLab is another deep-learned model that was built based on the DeepLabv3 + segmentation network and was fine-tuned and trained to efficiently classify skin regions. According to the fair comparison conducted in20, DeepLab was ranked the best performing method, while Cheddad was ranked the 12th due to being imprecise especially when dealing with complex background images.

However, despite the higher accuracy of the skin detection techniques discussed earlier, the hiding process may change the pixel values resulting in some pixels that were originally identified as “skin” pixels to be classified as “non-skin” after embedding. These changes introduced in the skin map will mislead the extraction process and eventually present errors in the retrieved message. Therefore, the authors’ former research22 proposed using a blocked version of the skin map to avoid error-prone skin pixels which often exists on the boundaries of the skin map. The idea was to divide the skin map into equal size square blocks and process them discarding any block that doesn’t purely consists of skin pixels. In other words, the new generated blocked map will include only those blocks with all ones. This step proved to reduce errors and hence enhance the quality of the extraction process. A 4 × 4 and 8 × 8 blocked skin map for the input image are shown in Fig. 3 (c) and (d), respectively.

Integer-to-Integer walvelet transform

Wavelets are functions that satisfy certain mathematical requirements and are used to process data at different scales or resolutions23. Like the retina of the eye, a wavelet multiresolution decomposition splits an image into several frequency channels or sub-bands of approximately equal bandwidth. This allows the signals in each channel to be processed independently24,25. In the case of one-dimensional discrete wavelet transform (DWT), the input to the decomposition process is a vector that is convolved with a high pass filter (\(\:\stackrel{\sim}{g}\)) and a low pass filter (\(\:\stackrel{\sim}{h}\)). The result of the latter convolution is a smoothed version of the input while the high frequency part is captured by the first convolution. This is followed by a sub-sampling step to resize these convolutions such that the result is half the size of the input26. The resulting high frequency coefficients are the detail coefficients at the finest level while the low frequency output represents a smoothed version of the input. The same procedure can be repeated on the input approximation resulting in wavelet coefficients at different levels of detail. All together, these coefficients constitute a multiresolution analysis of the input. On the other hand, the reconstruction process starts by up-sampling step which puts a zero in between every two coefficients then follows with a convolution using the filters g and h. finally, the results of these convolutions are added to form the original signal. Figure 4 depicts the steps of the one-dimensional WLT.

In the case of images, the one-dimensional DWT is first applied on all rows and then on all columns27. As shown in Fig. 5, this results in four classes of coefficients: HH is the result of the high-pass filter in both directions representing the diagonal features of the image. LH and HL result from a convolution with \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{g}\:\) in one direction and with \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{h}\) in the other, reflecting vertical and horizontal information respectively. The LL sub-band is the result of a low-pass convolution in both directions. The same decomposition can be repeated on the LL quadrant up to n times, where n is log2(min (height, width)).

Despite the fact that the image pixels are represented as integers, applying a 2D WLT on an image results in floating point coefficients. This, unfortunately, doesn’t allow perfect synthesis of the original image from its sub-bands. This is actually a critical issue facing WLT-based steganographic techniques where parts of the embedded data may be lost due to truncation errors. Therefore, Wavelet transforms that map integers-to-integers can be the answer to address that issue. One example is the S-transform which is considered a reversible Haar transform28. Equations (2) and (3) are used to compute the approximation (s) and detail (d) coefficients, respectively. On the other hand, Eqs. (4) and (5) can be used to synthesize the original signal. Notice that the computations still use floating point arithmetic, but the results are guaranteed to be integer and reversible. You can refer to29 for the generalized computations of the S-transform in two-dimensions.

The embedding module

In the following text, the cover image is referred to as C and the stego-image as S. Furthermore, the secret message is denoted by m, and its respective elements are denoted as mi where \(\:{m}_{i}\hspace{0.33em}\in\:\hspace{0.33em}\left\{0\hspace{0.33em},\hspace{0.33em}1\right\}\). When applied to a colored image, the DWT is usually computed for each color plane separately. Thus, we will refer to the coefficients by Ri(x, y), Gi(x, y), and Bi(x, y) where i = {a, h, v, d} (which stands for the approximation, horizontal, vertical, and diagonal sub-bands respectively) and x and y are the coordinates of the coefficient in a specific sub-band.

As shown in Fig. 2, the embedding process starts with applying one level S-transform on each color channel of the cover image. Combining the Ra, Ga, and Ba of C results in an averaged down-scaled version of the cover image. The downscaled image is used to generate a skin map that matches the scale and dimensions of a single approximation sub-band. This skin map is then divided into blocks, and only those blocks composed entirely of skin pixels are retained. As demonstrated in previous research13, this approach helps reduce errors that can occur when embedding data near the edges of skin regions. Once the blocked skin map is created, it guides the data hiding process: for each pixel marked as “skin” in the blocked map, the third least significant bit (LSB) of the corresponding Ra coefficient is replaced with a message bit. After using all Ra coefficients, Ga and Ba coefficients are manipulated as well to accommodate all the bits in the message m. Finally, the embedded Ra is combined with the yet unmodified Rh, Rv, and Rd to construct the Red plane of the cover image using the inverse S-transform. The same process is repeated for Ga and Ba to construct the Green and Blue color planes, respectively. The reconstructed RGB planes are then combined to form the stego-image SSS. It is important to note that the selected cover image must contain sufficiently large skin regions to accommodate the message mmm. If the available skin area is insufficient, the algorithm will reject the cover image CCC for failing the capacity check.2.4. The Extraction ModuleWhen the stego-image is received on the other side of the communication channel, an extraction process is needed to retrieve the hidden message. The steps of the extraction process are basically the same of the embedding but in a reversed order. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, the retrieval process starts with a one level S-transform on each color channel of the stego-image, where the combined Ra, Ga and Ba is used to generate the skin map. A blocking operation is then applied on the generated skin map to remove skin pixels falling outside a pure skin block. This blocked map will guide the extraction process from the Ra, Ga and Ba, respectively. That is, the 3rd LSB of each approximation coefficient will be read, aligned and eventually converted into its original digital format. For example, if the embedded message is a grey-scale image message, every 8 bits will form a pixel.

Results

The experimental design

In the following set of experiments, five cover images were selected from Pratheepan Dataset30. As shown in Fig. 6, the images show a variety of skin tones covering regions of different sizes. From left to right, the cover image file names are: 06Apr03Face.jpg, 920480_f520.jpg, 0520962400.jpg, 124511719065943_2.jpg and Aishwarya-Rai.jpg. The image dimensions are 360 × 516, 520 × 775, 277 × 298, 300 × 434, and 324 × 430 pixels, respectively. As far as the secret image is concerned, we used a grey-scale image that is scaled to fit within the skin areas available in each cover image.

Performance metrics

The performance of the proposed technique was evaluated with respect to several criteria. First, to measure the degradation caused by the embedding process we used the Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR). PSNR can be computed using (6) using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) as in (7). M and N represent the dimensions of the input images (I1, I2) and R reflects the maximum signal value that exists in the image data type. PSNR is measured in dB, where a value greater than 40 dB indicates that the stego-image closely resemble the original cover image.

Secondly, a Similarity metric will be used to assess the quality of the extracted image. This metric quantifies image quality degradation based on the difference between extracted message (M’) and the original one (M). It can be computed as a percentage using (8), where a higher value reflects a greater similarity between the secret image and the retrieved one and hence a higher extraction accuracy.

Furthermore, the Payload is used to measure the amount of information that can be hidden in each cover. In the case of images, payload is represented in Bits per Pixel (bpp) and is calculated as in Eq. (9).

Experimental results

In this section, we are going to analyze the performance of the proposed method (hiESBM). We would like to start our experiments with investigating the effect of block size on the secret image retrieval quality using three skin-detection techniques. As shown in Table 1, deeplab21 succeeded to provide the highest precision in detecting skin regions even after the embedding process took place. This obviously results in less differences between the skin map created before and after the embedding. In fact, in most of the test cases, the two maps were identical when using 8 × 8 blocks. Therefore, moving forward in our experiments, we decided to use the deeplab skin detection method as well as 8 × 8 block size.

Now, we can test the hiESBM performance when utilizing different color channels of the cover image for hiding. In fact, we explored using only one color (namely blue) channel, two color channels, and the full color channels. As shown in Table 2, the hiding capacity of each test image is computed in pixels. The PSNR values shows the high invisibility of the proposed method even when utilizing all color channels. In addition, since hiESBM succeeded to minimize the difference between the skin map before and after embedding, the similarity values are high reaching 100% in most of the cases.

We also noticed that the performance of hiESBM depends heavily on the individual characteristics of the chosen cover image, which makes it quite challenging to decide which or how many color channels to use for embedding. For example, in the case of 06Apr03Face the secret image was extracted with 100% for all color channel combination. Thus, it is possible to utilize the full RGB space in this case. The 124511719065943_2 experiment, on the other hand, showed that RB channels should be avoided since it introduced errors in the skin detection process which reduced the similarity measure. More interestingly, the Aishwarya-Rai experiment showed the least retrieval quality among the experiments for all tested color channel combinations. In conclusion, we recommend testing different cover images to maximize both the capacity and the extraction accuracy. Table 3 shows sample cases to visually demonstrate low retrieval accuracy.

While the proposed method demonstrates promising results in terms of imperceptibility and recovery accuracy, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the use of wavelet transforms and the skin-based masking mechanism adds computational overhead, particularly during the preprocessing and embedding stages. This may impact scalability when applied to large datasets or real-time applications. Second, the accuracy of skin region detection is sensitive to variations in lighting conditions, skin tones, and background complexity, which can affect the consistency of the embedding mask. Finally, the method’s performance may vary across different types of images. It performs best on high-resolution images with clear foreground-background contrast and may be less effective on low-contrast or uniformly textured images.

Discussion

The goal of this set of experiments is to discuss the performance of the proposed method in comparison with some existing ones. The comparison focuses on the three quantitative metrics: PSNR, accuracy of retrieval (similarity), and the payload (bbp). Table 4 shows the methods in their referenced publications as well as the hiding approach they followed. All of the listed methods use images as the secret data.

The results show that the proposed method (hiESBM) provides the highest similarity between the extracted image and the embedded one. At the same time, hiESBM outperformed the other methods in terms of invisibility. However, in its pursuit of high invisibility, hiESBM couldn’t beat the hiding capacity of some of the listed methods. In fact, the closest PSNR value was achieved by our predecessor method SBM. However, the proposed method succeeded to offer more than 10 times the hiding capacity offered by SBM. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the published results for FRnTW10 lacked a clear discussion on recoverability of their proposed method especially with the low hiding capacity offered. Furthermore, the experiments used only two colored cover images of size 512 × 512 to hide a 64 × 64 greyscale image, which doesn’t provide enough evidence for the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Conclusions

In this research, we introduced a wavelet-domain image steganography method that integrates a skin-based masking strategy and a lightweight bit-matching embedding rule to achieve high visual fidelity and effective information recovery. During the hiding process, the approximation sub-band of the cover image is used to build a blocked skin-map. That is, only coefficients that correspond to “skin” pixels will be modified to carry the message bits. Comprehensive experimental results were carried to test the retrieval accuracy using different skin detections methods and block sizes. The results showed that the best performance was developed using 8 × 8 block size and the deeplab skin detection method. The hiding capacity of the proposed method reached 2.3 bpp when utilizing the full color space for embedding which is more than 10 times the capacity offered by its predecessor ESBM. Comparisons with some existing techniques demonstrated that the proposed method performs competitively offering outstanding invisibility and extraction accuracy.

We also acknowledge several limitations of the current approach. These include sensitivity to lighting variations in skin detection, dependence on image content and resolution, and the absence of a comprehensive evaluation against steganalysis tools. Future work could involve evaluating the system’s robustness against common image processing attacks—such as JPEG compression—to broaden its applicability, particularly in areas like invisible image watermarking. Another valuable direction would be to assess the steganographic security of the proposed method by subjecting it to standard steganalysis techniques, with the aim of improving its resistance to detection.

Appendix A

Data availability

The set of cover images used and analyzed during the current study were selected from Pratheepan Dataset that is publicly available at http://cs-chan.com/downloads_skin_dataset.html.

References

Information hiding terminology. In Information Hiding. IH 1996. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 1174 (ed. Anderson, R.) (Springer, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-61996-8_52.

Fridrich, J. Steganography in Digital Media: Principles, Algorithms, and Applications (Cambridge University Press, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139192903

Aberna, P. & Agilandeeswari, L. Digital image and video watermarking: methodologies, attacks, applications, and future directions. Multimed Tools Appl. 83, 5531–5591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-15806-y (2024).

Cheddad, A. et al. Digital image steganography: survey and analysis of current methods. Signal. Process. 90 (3), 727–752 (2010).

Ahmidi, N. & Neyestanak, A. L. A Human Visual Model for Steganography. Proc IEEE Canadian Conf Electrical Computer Engineering (CCECE)pp 1077–1080 (Niagara Falls, ON, 2008).

Fakhredanesh, M., Rahmati, M. & Safabakhsh, R. Steganography in discrete wavelet transform based on human visual system and cover model. Multimed Tools Appl. 78, 18475–18502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-7238-8 (2019).

Sowmya, K. B., Bhat, P. S. & Hegde, S. Implementation of image encryption by steganography using discrete wavelet transform in verilog. In Advances in Multidisciplinary Medical Technologies Engineering, Modeling and Findings (eds Khelassi, A. & Estrela, V. V.) (Springer, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57552-6_15.

Yadahalli, S. S., Rege, S. & Sonkusare, R. Implementation and analysis of image steganography using Least Significant Bit and Discrete Wavelet Transform techniques, 2020 5th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 2020, pp. 1325–1330. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCES48766.2020.9137887

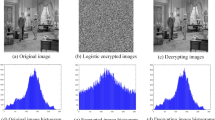

Valandar, M. Y., Ayubi, P. & Barani, M. J. A new transform domain steganography based on modified logistic chaotic map for color images, Journal of Information Security and Applications, Volume 34, Part 2, Pages 142–151, ISSN 2214 – 2126, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2017.04.004

Sivaramakrishnan, U., Panga, N. & Rajini, G. K. Image Steganography based on Fractional Random Wavelet Transform and Arnold Transform with cryptanalysis. In 2021 International Conference on Computing, Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS) (pp. 618–623). IEEE. (2021), February.

Rabie, T., Kamel, I. & Baziyad, M. Maximizing embedding capacity and Stego quality: curve-fitting in the transform domain. Multimedia Tools Appl. 77, 8295–8326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4727-5 (2018).

Ghosal, S. K., Chatterjee, A. & Sarkar, R. Image steganography based on Kirsch edge detection. Multimedia Syst. 27 (1), 73–87 (2021).

Damghani, H., Babapour Mofrad, F. & Damghani, L. Medical JPEG image steganography method according to the distortion reduction criterion based on an imperialist competitive algorithm. IET Image Proc. 15 (3), 612–626. https://doi.org/10.1049/ipr2.12055 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Invertible Mosaic Image Hiding Network for Very Large Capacity Image Steganography. arXiv, arXiv:2309.08987. (2023). https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.08987

Sadek, M. M., Khalifa, A. & Khafga, D. March. An enhanced Skin-tone Block-map Image Steganography using Integer Wavelet Transforms. In 2022 5th International Conference on Computing and Informatics (ICCI) (pp. 378–384). IEEE. (2022).

Lakshmi, H. C. V. & Kulkarni, S. P. Face detection algorithm for skintone images using robust feature extraction in HSV color space, in IJCA special issue on recent trends in pattern recognition and image analysis RTPRIA, vol. 1, pp. 27–32, (2013).

Cheddad, A., Condell, J., Curran, K. & Mc Kevitt, P. A skin tone detection algorithm for an adaptive approach to steganography. Sig. Process. 89 (12), 2465–2478 (2009).

Kakumanu, P., Makrogiannis, S. & Bourbakis, N. A survey of skin-color modeling and detection methods. Pattern Recogn. 40 (3), 1106–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2006.06.010 (2007).

Badrinarayanan, V., Kendall, A. & Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39 (12), 2481–2495 (2017).

Lumini, A. & Nanni, L. Fair comparison of skin detection approaches on publicly available datasets. Expert Syst. Appl. 160, 113677 (2020).

Chen, V., Zhu, L. C., Papandreou, Y., Schroff, G. & Adam, H. F. and Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) (pp. 801–818). (2018).

Sadek, M. M., Mostafa, M. G. & Khalifa, A. S. A skin-tone block-map algorithm for efficient image steganography. In 2014 9th International Conference on Informatics and Systems (pp. DEKM-27). IEEE. (2014), December.

Drori, A. I. & Lischinski, D. Wavelet Warping, School of Computer Science and Engineering (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2000).

Kundur, D. & Hatzinakos, D. Digital watermarking using multiresolution wavelet decomposition. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, ICASSP’98 (Cat. No. 98CH36181) (Vol. 5, pp. 2969–2972). IEEE. (1998), May.

Kundur, D. & Hatzinakos, D. A robust digital image watermarking method using wavelet-based fusion. In Proceedings of International Conference on Image Processing (Vol. 1, pp. 544–547). IEEE. (1997), October.

Saha, S. Image Compression - from DCT to Wavelets: A Review, Technical report, (1999). [http://my.engr.ucdavis.edu/~ssaha/crossroads/sahaimagecoding.html]

Bernd Girod, F., Hartung, U. & Horn Multiresolution Coding Of Image And Video Signals, Invited paper, Rohdes, Greece, (1998).

Calderbank, A. R., Daubechies, I., Sweldens, W. & Yeo, B. L. Wavelet transforms that map integers to integers. J. Appl. Comput. Harmonic Anal. (ACHA). 5 (3), 332–369 (1998).

Tolba, M. F., Ghonemy, M. A., Taha, I. A. & Khalifa, A. S. Using integer wavelet transforms in colored image steganography. Int. J. Intell. Coop. Inform. Syst. 4 (2), 230–235 (2004).

Tan, W. R., Chan, C. S., Yogarajah, P. & Condell, J. A fusion approach for efficient human skin detection. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 8 (1), 138–147 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers for Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R409), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R409), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Resources: E.A.A., D.S.K.; Conceptualization: A.K., D.S.K., M.S.; original Draft Writing: A.K., D.S.K., M.S.; Methodology: A.K., D.S.K., M.S.; Software: E.A.A., D.S.K.; Validation: E.A.A., D.S.K.; Investigation: D.S.K.; Data Curation: E.A.A., D.S.K.;A.K.,M.S;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalifa, A., Khafaga, D.S., Sadek, M. et al. An enhanced adaptive image steganography method using block skin-maps and the integer S-transform. Sci Rep 15, 44242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16176-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16176-1