Abstract

Frailty is an important health issue in older adults that leads to disability and increased mortality. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW), a measure of variability in red blood cell volume, is associated with inflammation, anemia, and cardiovascular diseases. This study examined whether high RDW (≥ 13.5%) predicts incident frailty over three years in 469 older adults with cardiometabolic disease but without baseline frailty, as defined by the modified Cardiovascular Health Study (mCHS) criteria or the Kihon Checklist (KCL). RDW was measured through a complete blood cell count. Multivariate Cox regression estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for high RDW and incident frailty, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, eGFR, HbA1c, and basely ne mCHS or KCL score, with low RDW as the reference. During the follow-up period, 29.5% and 24.6% of the patients developed frailty, as defined by the mCHS and KCL, respectively. High RDW was significantly associated with incident mCHS- and KCL-defined frailty, with adjusted HRs of 1.62 (95% CI: 1.10–2.37) and 1.49 (95% CI: 1.02–2.34), respectively. Thus, elevated RDW levels (≥ 13.5%) were found to be an independent predictor of the incidence of two distinct types of frailty in older adults with cardiometabolic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frailty is a vulnerable state in which functional reserves decline with age, and stress can lead to disability, hospitalization, and death1. There are several definitions of frailty, including phenotypic frailty, weight loss, fatigue, muscle weakness, physical inactivity, and reduced walking speed1 as well as frailty based on comprehensive geriatric assessment2 and frailty in a deficit accumulation model3. Frailty occurs in various conditions, including malnutrition4, inflammation5, diabetes mellitus6, cardiovascular disease7, cognitive impairment8, anemia9, and polypharmacy10. As frailty is a reversible condition that can be expected to improve with appropriate intervention1, it is important to identify a marker that can easily assess the risk of developing frailty using blood samples in the usual clinical setting.

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is a measure of the variability in red blood cell volume and can be easily and inexpensively measured by complete blood count. An increased RDW level is associated with malnutrition11,12, inflammation12, diabetes (hyperglycemia)13, hypertension14, cardiovascular disease15, chronic kidney disease (CKD)16, dementia17, and anemia (ineffective erythropoiesis)18, which are similar to the factors associated with frailty. High RDW is considered a novel predictor of mortality in patients with heart failure, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary embolism, cancer, sepsis, and critically ill patients18.

Although RDW or hemoglobin-to-RDW ratio has been reported to be associated with frailty in several cross-sectional studies19,20,21,22, few longitudinal studies have been conducted on the relationship between evaluated RDW and frailty development. Only one study has shown an association between high RDW and progression to frailty or death in community-dwelling older men23. Therefore, we investigated whether RDW was associated with incident frailty in a longitudinal study of outpatients with cardiometabolic diseases who were at a high risk of frailty.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The clinical characteristics of the participants in the study of incident, modified Cardiovascular Health Study (mCHS)-defined frailty, and Kihon Checklist (KCL)-defined frailty are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. In the analysis of mCHS-defined frailty, the median age was 78 years, and 62.0% of the patients were women. The prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, and ischemic heart disease (IHD) were 48.3, 75.0, 64.2, 10.5, and 13.4%, respectively. According to the mCHS criteria, 70.0% were pre-frailty, and 30.0% were robust (Table 1). Two participants were taking oral iron tablets at the baseline, and their RDW levels at the baseline were 14.4% and 15.7%, respectively.

Baseline characteristics in groups with low and high RDW

The high-RDW group had older age, higher prevalence of hypertension, and lower mCHS scores, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), handgrip strength, Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores, and scores on the Japanese version of the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) at baseline than the low-RDW group (Table 1).

RDW and development of frailty

In the analysis of 424 patients without frailty at baseline, 125 (29.5%) developed mCHS-defined frailty during a median follow-up period of 1079 days (quartiles: 494–1545 days). Of the 378 patients without frailty at baseline, 82 (24.6%) developed KCL-defined frailty during a median follow-up period of 1057 days (quartiles: 443–1477 days). The incidence of mCHS-defined frailty was significantly higher in those with a high RDW than those with a low RDW (38.7% vs. 21.3%, p < 0.05). Similarly, the high-RDW group had a higher incidence of KCL-defined frailty than the low-RDW group (32.0% vs. 18.8%, p < 0.05).

Kaplan–Meier survival analyses

The frailty-free survival curves according to the definitions of mCHS and KCL in the low- and high-RDW groups are shown in Figs. 1A and 1B, respectively. Log-rank tests showed that the high-RDW group was more likely to have incident frailty according to the mCHS and KCL (p < 0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively).

The frailty-free survival curves according to the definition of (A) mCHS and (B) KCL by the low- and high-RDW groups The low- and high-RDW groups were defined as those with RDW < 13.5% and ≥ 13.5%, respectively. The high-RDW group was more likely to have incident frailty according to their mCHS and KCL scores (p < 0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively, log-rank test).RDW: red blood cell distribution width, mCHS: modified version of the Cardiovascular Health Study, KCL: Kihon Checklist.

Cox regression analyses

The results of the Cox regression analysis are presented in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2. The age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the incidence of mCHS-defined and that of KCL-defined frailty in the high-RDW group were 1.80 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.25–2.60) and 1.64 (95% CI: 1.11–2.42), respectively, with the low-RDW group as reference (Model 1). Next, in Model 2, further adjusted for body mass index (BMI), eGFR, HbA1c, and baseline mCHS score, the HR values for incident frailty according to the mCHS and KCL were 1.62 (95% CI: 1.10 to 2.37) and 1.54 (95% CI: 1.02 to 2.34), respectively. Even when hemoglobin was added to Model 2, the association between high RDW and mCHS-defined and KCL-defined frailty was significant or reached significance (HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.30 and HR = 1.50, 95% CI: 0.98 to 2.28, respectively). Furthermore, the association between a high RDW and both types of frailty remained significant in the analyses adjusted for high-sensitive CRP test (hsCRP) (Model 4), albumin (Model 5), and MMSE (Model 6), in addition to the covariates in Model 2 (Supplementary Table S2). An additional analysis was performed in which Model 2 was adjusted for either polypharmacy (Model 7) or the Lubben Social Network Scale-6 (LSNS-6) score (Model 8). The high-RDW group remained at significantly higher risk of developing m-CHS-defined frailty than the low-RDW group, and the risk of developing KCL-defined frailty was also higher in the high-RDW group (Supplementary Table S2). We found no interaction effects of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or CKD on the association between high RDW and mCHD-defined frailty.

Discussion

This study showed that a higher RDW (≥ 13.5%) was associated with the incidence of frailty according to the mCHS and KCL in a longitudinal study of older outpatients with cardiometabolic disease. These results are consistent with those of previous cross-sectional studies showing an association between RDW and prevalent frailty19,20,21,22. Some studies have shown an association between a high RDW (≥ 15.7%) and frailty, as assessed using the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Index (malnutrition, poor physical performance, and fatigue) in community-dwelling older adults20. In a study of older patients with coronary heart disease, higher RDW (≥ 13.5%) was associated with mCHS-defined frailty21. As only one longitudinal study by Kim et al. showed an association between high RDW (≥ 15.1%) and the combined outcome of frailty or mortality, a clear association between RDW and incident frailty has not been demonstrated23. This is the first longitudinal study to show that high RDW (≥ 13.5%) was associated with the incidence of KCL-defined frailty, based on comprehensive geriatric assessment, as well as mCHS-defined frailty (frailty phenotype) in older outpatients with cardiometabolic diseases.

RDW is a measure of anisocytosis or variability in red blood cell size and is associated with anemia and many other diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, infection, and cancer18. As a high RDW is a strong risk factor for mortality in these patients, those with high RDW values should be more closely monitored and intensively managed to improve clinical outcomes18. High RDW can be reduced by exercise training24, nutritional supplementation25, and anti-inflammatory drugs such as colchicine and statins26,27. Because RDW is a simple and inexpensive test that can be performed during a complete blood count, the measurement of RDW may be useful for the early detection of frailty and monitoring the effectiveness of frailty interventions in older adults at high risk for frailty. Importantly, it is shown in the current study that the association between RDW and frailty was observed independent of BMI, eGFR, and HbA1c, which are also known to be associated with frailty and easy to measure at outpatient clinics. Our results suggest that by adding RDW and combining it with established frailty risk factors, we can estimate the risk of incident frailty more accurately in patients with cardiometabolic disease. Awareness of RDW could contribute to improving geriatric physicians’ prediction of frailty in routine outpatient settings.

Although the cause of the association between RDW and incident frailty remains unknown in this study, inflammation and anemia may be involved in the common mechanism of red cell abnormalities and frailty development. In a meta-analysis, inflammatory markers, such as CRP, interleukin-6, white blood cells, and fibrinogen, have been associated with frailty3. However, in this study, hsCRP levels were similar between the high- and low-RDW groups and the significant association between high RDW and incident frailty persisted after adjustment for CRP. Therefore, the association between high RDW and frailty is likely mediated by factors other than inflammation or subtle local inflammation that is not reflected in CRP levels. Because the association between high RDW and incident frailty was slightly attenuated after adjustment for hemoglobin, the association may have been partially mediated by anemia.

Mitochondrial dysfunction28 and oxidative stress29 have been considered to be involved in frailty development. In our previous longitudinal study, high levels of serum growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), a marker of mitochondrial dysfunction, were associated with frailty30. Increased RDW in a mouse model of hypoxia has been reported to be reduced and lifespan extended when the gene encoding succinate dehydrogenase in mitochondrial complex II was knocked out31. A systematic review demonstrated that frailty and prefrailty appear to be associated with higher levels of oxidative stress markers, such as malondialdehyde and isoprostanes, and lower antioxidant parameters, such as vitamins C and E29. The in-vitro induction of oxidative stress to red blood results in increased RDW and decreased erythrocyte volume32. In some studies, high RDW values have been associated with increased membrane lipid peroxidation in patients with coronary heart disease33. Thus, the association between high RDW and incident frailty may be mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, which were not assessed in this study.

Because diabetes mellitus, hypertension, CKD, and ischemic heart disease are reportedly associated with RDW and frailty6,7,13,14,15,16, the association between high RDW and incident frailty may be explained by vascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease. However, there were no significant associations between high RDW and the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, or ischemic heart disease in our study, although eGFR decreased in those with high RDW. Furthermore, the association between RDW and frailty persisted even after adjusting for HbA1c level, systolic blood pressure, and eGFR. Therefore, vascular risk factors or cardiovascular diseases may not explain the association between high RDW and incident frailty. Further basic and clinical research is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms mediating high RDW and the development of high RDW and frailty.

This study has several strengths. First, it is a longitudinal study with a relatively large sample of patients with cardiometabolic diseases who are at high risk for frailty, and their frailty status was evaluated multiple times. Second, the study examined the predictive ability of RDW for the incidence of two types of frailty: mCHS-defined frailty, a frailty phenotype, and KCL-defined frailty, a frailty based on CGA. Third, we found that the association between high RDW and incident mCHS-defined frailty remained significant even after adjusting for BMI, HbA1c, renal function, hsCRP, cognition, polypharmacy, and social network as potential confounders.

However, this study also had several limitations. First, it was conducted exclusively at a single center and predominantly included Japanese older adults with cardiometabolic diseases. Because it is known that those with cardiometabolic diseases show higher RDW levels than those without such diseases, it is expected that the cut-off value of RDW for predicting incident frailty differs from that of the population without cardiometabolic diseases. However, because other factors such as ethnicity and BMI may influence the strength of the association and its cut-off point, caution is needed when we try to extrapolate our results to other populations with cardiometabolic diseases. Second, other confounders for which we did not collect data in this study may remain. Although the LSNS-6 had little influence on the association between RDW and frailty incidence, we could not rule out the possibility that social factors that could not be assessed may have influenced the association between high RDW and the development of frailty. Furthermore, comorbidities that we did not take into account may also have affected the results.

Third, this study may have been affected by bias owing to untraceable interruptions in following up after the initial visit. Reasons for loss to follow-up included unwillingness to participate in the frailty examination due to fear of infection during the pandemic, transfer to another institution or clinic, and loss of interest. Because the latter half of our study period overlapped with the pandemic, many patients who were lost to follow-up were unwilling to make an additional visit or extend their frailty evaluations at the Frailty Clinic.

In conclusion, in this longitudinal study, high RDW values were associated with the incidence of the two types of frailty in older patients with cardiometabolic diseases. Because RDW is easy and inexpensive to perform with a complete blood count, measuring the complete blood count could contribute to identifying patients at high risk of developing frailty and conducting early interventions such as nutrition, exercise, and social support. However, further clinical and basic research is needed to determine whether interventions to reduce RDW, such as exercise and anti-inflammatory or antioxidative agents, can prevent frailty.

Methods

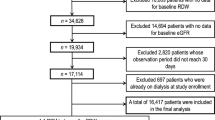

Participants

A total of 884 patients with cardiometabolic diseases and symptoms of frailty who were referred to the frailty clinic23 from the Department of Diabetes, Metabolism, and Endocrinology or Cardiology between Aug 2015 and October 2023 were included. The required sample size was calculated based on the following assumptions: estimated incidence of frailty during the observational period in the low-RDW and high-RDW groups are 30% and 45%, respectively, with a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a power of 0.80. Based on these parameters, the required sample size was calculated as 352 (176 per each group). Assuming a dropout rate of 20%, the total number was calculated as 440. Fifteen patients aged < 65 years were excluded. In patients with cardiovascular diseases, mainly diabetes and hypertension, advanced stages are frequently accompanied by renal impairment, which itself influences RDW levels and patients’ prognosis. As our aim was to clarify the association between RDW and frailty in patients with cardiometabolic diseases independent of renal dysfunction, we excluded those with severe renal impairment, defined as serum creatinine levels of > 2 mg/dl (Fig. 2). All participants were assessed for frailty according to the modified version of the CHS criteria (mCHS)34 and KCL35 at their first visit to the frailty clinic. Those with frailty according to both the mCHS and KCL criteria at baseline (n = 191) were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 2). Moreover, those who could not be followed up for the development of frailty (n = 185) were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 2). The remaining 469 participants were followed up annually for as long as possible to determine whether they developed mCHS- or KCL-defined frailty.

Laboratory examinations

All of the participants underwent blood tests during their frailty clinic visits. RDW was measured using an automatic hematology analyzer (XR-3000; SYSMEX, Kobe, Japan) when a complete blood cell count was performed. High and low RDW were defined as ≥ 13.5% and < 13.5%, respectively, using the previously reported cutoff level21,36.

Biochemical tests were performed to measure albumin, creatinine, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), LDL, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglyceride (TG), and hsCRP. The eGFR was then calculated from the serum creatinine levels, age, and sex using the standard Japanese method37.

Assessment of frailty

mCHS-defined frailty was diagnosed as having three or more of the following components: weight loss, low handgrip strength, exhaustion, low walking speed, and low physical activity based on the criteria by Fried et al1 and modified to be adapted to the Japanese population. Those with one or two of these components were defined as pre-frailty, whereas those with none were defined as robust. Weight loss was assessed by an interview for weight loss of > 2–3 kg. Exhaustion was assessed by interviews regarding the presence of feeling tired without a reason in the last two weeks. Low walking speed was defined as less than 1.0 m/s on the 4 m walking test. Low physical activity was assessed through an interview based on whether the participant went out less than once a week or the frequency had decreased from the previous year34. Low handgrip strength was defined as less than 18 kg for women and 28 kg for men based on the Asia Walking Group for Sarcopenia criteria38.

The KCL was developed by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare for the prevention of care for older adults, and KCL-defined frailty is defined as having at least eight out of 25 items that consist of instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), physical function, falls, nutrition, oral, social withdrawal, cognition, and depression25. Those with four to seven of these items were defined as having pre-frailty, and those with three or fewer items were defined as robust.

Body composition

Body composition was measured at the frailty clinic visit using an InBody770® (InBody Japan, Tokyo, Japan) based on bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA)39. Body fat percentage and skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), which is the total lean body mass of the extremities divided by the square of the height (kg/m2), were calculated.

Assessment of comorbidities and physical examination

All participants were interviewed regarding comorbidities at their first frailty clinic visit, and the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension (HT), dyslipidemia, stroke, and IHD was calculated. Height, weight, and blood pressure were measured for all participants, and BMI was calculated.

Assessment of nutrition, cognitive function, and social network

Nutritional status was assessed using the Mini-Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF)40. Cognitive function was assessed by the MMSE41. Social network was assessed by the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale-6 (LSNS-6)42.

Assessment of polypharmacy

The number of medications being taken was counted for all participants, and if they were taking five or more medications, they were determined to have polypharmacy.

Statistical analysis

Differences in categorical and continuous variables between the low- and high-RDW groups were assessed using the chi-square test and the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Frailty-free survival curves based on the low- and high-RDW groups were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Furthermore, to examine the independent association between high RDW and incident frailty, we performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis with RDW (high/low) as an explanatory variable. HRs and 95% CIs for incident frailty according to the mCHS and KCL criteria were calculated using low RDW as a reference in the following models: Model 1, adjusted for age and sex; Model 2, further adjusted for BMI, eGFR, HbA1c, and baseline mCHS or KCL score; and Model 3, further adjusted for hemoglobin levels. Additional multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed using the covariates in Model 2 plus hsCRP (Model 4), albumin (Model 5), MMSE (Model 6), polypharmacy (Model 7), or LSNS-6 score (Model 8). All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics 20 software package (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). To explore the interaction effect of comorbidities on high RDW and frailty, Cox regression analyses stratified by diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or CKD (eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2) were conducted. For all comparisons, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available and can compromise patient privacy.

References

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M156 (2001).

Pilotto, A. et al. A multidimensional approach to frailty in older people. Ageing Res. Rev. 60, 101047 (2020).

Searle, S. D., Mitnitski, A., Gahbauer, E. A., Gill, T. M. & Rockwood, K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 8, 24 (2008).

Lorenzo-López, L. et al. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 17, 108 (2017).

Soysal, P. et al. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 31, 1–8 (2016).

Hanlon, P. et al. Frailty measurement, prevalence, incidence, and clinical implications in people with diabetes: A systematic review and study-level meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 1, e106–e116 (2020).

Marinus, N. et al. Frailty is highly prevalent in specific cardiovascular diseases and females, but significantly worsens prognosis in all affected patients: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 66, 101233 (2021).

Vahedi, A. et al. Cognitive impairment in people with physical frailty using the phenotype model: A systematic review and meta analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 37, 10 (2022).

Lee, C. T. et al. Prevalence of anemia and its association with frailty, physical function and cognition in community-dwelling older adults: Findings from the HOPE study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 25, 679–687 (2021).

Gutiérrez-Valencia, M. et al. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 84, 1432–1444 (2018).

Haenggi, E. et al. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) - A new nutritional biomarker to assess nutritional risk and response to nutritional therapy?. Clin. Nutr. 43, 575–585 (2024).

Förhécz, Z. et al. Red cell distribution width in heart failure: Prediction of clinical events and relationship with markers of ineffective erythropoiesis, inflammation, renal function, and nutritional state. Am. Heart J. 158, 659–666 (2009).

Yin, Y. et al. Red blood cell distribution width and the risk of being in poor glycemic control among patients with established type 2 diabetes. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 14, 265–273 (2018).

Chen, Y., Hou, X., Zhong, J. & Liu, K. Association between red cell distribution width and hypertension: Results from NHANES 1999–2018. PLoS ONE 19, e0303279 (2024).

Ainiwaer, A. et al. Association of red cell distribution width (RDW) and the RDW to platelet count ratio with cardiovascular disease among US adults: A cross-sectional study based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2020. BMJ Open 13, e068148 (2023).

Lippi, G. et al. Relationship between red blood cell distribution width and kidney function tests in a large cohort of unselected outpatients. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 68, 745–748 (2008).

Weuve, J., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Bennett, D. A., Dong, X. & Evans, D. A. The red cell distribution width and anemia in association with prevalent dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Dis. 28, 99–105 (2014).

Yousefi, B. et al. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in multiple clinical studies. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 24, 49–54 (2020).

Li, Q., Chen, X. & Han, B. Red blood cell distribution width is associated with frailty in older inpatients in China: Sex differences in a cross-sectional study. Exp. Gerontol. 150, 111392 (2021).

Li, C. M., Chao, C. T., Chen, S. I., Han, D. S. & Huang, K. C. Elevated red cell distribution width is independently associated with a higher frailty risk among 2,932 community-dwelling older adults. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 7, 470 (2020).

Hou, P. et al. Inflammation markers are associated with frailty in elderly patients with coronary heart disease. Aging (Albany NY) 10, 2636–2645 (2018).

Kinoshita, K. et al. Physical frailty and hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio in Japanese older outpatients. J. Frailty Aging 11, 393–397 (2022).

Kim, K. M. et al. Association between variation in red cell size and multiple aging-related outcomes. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 1288–1294 (2021).

Nishiyama, Y. et al. Effect of exercise training on red blood cell distribution width as a marker of impaired exercise tolerance in patients with coronary artery disease. Int. Heart J. 57, 553–557 (2016).

Sharp, J. et al. Coenzyme Q supplementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Redox Biol. 2, 884–891 (2014).

Seçkin, H. Y., Bütün, I., Baş, Y., Takcı, Z. & Kalkan, G. Effects of colchicine treatment on mean platelet volume and the inflammatory markers in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 27, 389–391 (2016).

Kucera, M. et al. The effects of atorvastatin treatment on the mean platelet volume and red cell distribution width in patients with dyslipoproteinemia and comparison with plasma atherogenicity indicators–A pilot study. Clin. Biochem. 48, 557–561 (2015).

Buondonno, I., Sassi, F., Cattaneo, F. & D’Amelio, P. Association between immunosenescence, mitochondrial dysfunction and frailty syndrome in older adults. Cells 12, 44 (2022).

Soysal, P. et al. Oxidative stress and frailty: A systematic review and synthesis of the best evidence. Maturitas 99, 66–72 (2017).

Oba, K. et al. Serum growth differentiation factor 15 levels predict the incidence of frailty among patients with cardiometabolic diseases. Gerontology 70, 517–525 (2024).

Baysal, B. E. et al. Succinate dehydrogenase inversely regulates red cell distribution width and healthy life span in chronically hypoxic mice. JCI Insight 7, e158737 (2022).

Joosse, H.-J. et al. In-vitro and in-silico evidence for oxidative stress as drivers for RDW. Sci. Rep. 13, 9223 (2023).

Namazi, G. et al. Relationship between red cell distribution width and oxidative stress indexes in patients with coronary artery disease. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 12, 241–250 (2023).

Tamura, Y. et al. Prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and sarcopenia in outpatients with cardiometabolic disease in a frailty clinic. BMC Geriatr. 18, 64 (2018).

Satake, S. et al. Validity of the Kihon Checklist for assessing frailty status. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 16, 709–715 (2016).

Cetin, S. et al. RDW value may increase the diagnostic accuracy of MPS. Medical Bulletin of Sisli Etfal Hospital 55, 76–80 (2021).

Matsuo, S. et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 53, 982–992 (2009).

Chen, L.-K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300-307.e2 (2020).

Varlet-Marie, E., Joré, C. & Brun, J. F. Segmental bioelectrical impedance analysis (SBIA) and blood rheology: Reducing the gap between in vivo and in vitro?. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 64, 603–611 (2016).

Rubenstein, L. Z., Harker, J. O., Salvà, A., Guigoz, Y. & Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56(M366), M372 (2001).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–188 (1975).

Kurimoto, A. et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 48, 149–157 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank everyone who committed to and/or practiced at our frailty clinic. This study was supported by a grant from the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (28-30) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KO, YT, and AA designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote a draft of the manuscript. JI, YM, and FY contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation. AH, RK,AT, KT, AI, TH, YC, and YF contributed to the data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AA has received speaker honoraria from Sumitomo Parma Co. Ltd. and Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd. KO, YT, JI, YM, FY, RK, AT, KT, YC, AI, TH, and YF have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology (#R15-20) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oba, K., Tamura, Y., Ishikawa, J. et al. High red blood cell distribution width associated with incident frailty in patients with cardiometabolic diseases: A longitudinal study. Sci Rep 15, 30907 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16216-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16216-w