Abstract

This paper proposes an innovative approach that combines a QMIX algorithm (a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm, MADRL) with a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) algorithm for optimizing intelligent path planning and scheduling of mining trucks in open-pit mining environments. The focus of this method is twofold. Firstly, it achieves collaborative cooperation among multiple mining trucks using the QMIX algorithm. Secondly, it integrates the GMM algorithm with QMIX for modeling, predicting, classifying and analyzing existing vehicle outcomes, to enhance the navigation capabilities of mining trucks within the environment. Through simulation experiments, the effectiveness of this combined algorithm was validated in improving vehicle operational efficiency, reducing non-working waiting time, and enhancing transportation efficiency. Moreover, this research compares the results of the algorithm with single-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithms, demonstrating the advantages of multi-agent algorithms in environments characterized with multi-agent collaboration. The QMIX-GMM mixed framework outperformed traditional approaches as complexity increased in the mining environments. The study provides new technological insights for intelligent planning of mining trucks and offers significant reference value for the automation of multi-agent collaboration in other environments. The limitation has been with regard to the maximum fleet size considered in the study being suitable to small or mid-scale mines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Path planning and scheduling systems in open-pit mining face several significant challenges, chiefly due to the dynamic and complex nature of mining operations. Some of the most critical issues include high operational costs, environmental degradation, inefficiencies in truck dispatching, and the inability of traditional math models to handle real-time decision-making effectively1. Among various tasks as drilling, blasting, loading and hauling, the haulage and transportation operations account for up to 70% of total mining costs2,3. In addition, the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from large dump trucks contribute significantly to environmental concerns1,3. The variability of the mining environment such as fluctuations in traffic congestion, sudden breakdowns of gear or equipment, and variations in ore quality and physical properties – in traditional dispatch strategies, including static allocation and rule-based heuristics, have proven inadequate for real-time decision making4. The integration of intelligent algorithms presents a promising avenue to address these limitations, allowing for improved efficiency and sustainability in mining operations.

The operation research (OR)-based approaches, such as linear programming, integer programming5and mixed-integer programming6 – have historically designed mining schedules that minimize idle time and waiting periods of shovels. Queuing theory and goal programming have further refined dispatch strategies under strict operational constraints7,8. However, the deterministic structure of these methods does not accommodate stochastic fluctuations, resulting in the need for re-optimization, which increases computational delay9.

Discrete Event Simulation (DES) provides the ability to handle unpredictability, but is resource-intensive and not suitable for on-the-fly scheduling10,11. Shifting to Industry 4.0—including the Internet of Things, big-scale data analytics, and automated decision systems12- there is a need for an autonomous, adaptive fleet management solution that can quickly process high-dimensional data streams and deliver robust performance even under uncertain conditions.

As a solution to these challenges, Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) have emerged as an important alternative where agents learn optimal policies by continuously interacting with the environment4. In the industrial domain, RL has optimized ride-hailing dispatch in DiDi via semi-Markov decision processes and deep value networks13improved aircraft recovery scheduling under disruption scenarios14and enhanced the scheduling of electric ready-mix concrete vehicles to support decarbonization15.

Within intelligent transportation systems, DRL-based traffic signal control and automated vehicle routing have smoothed flow and reduced congestion16. In port operations, spatial-attention DRL models take into account uncertainties in truck speeds, crane service times, and yard congestion, thereby increasing throughput17. Specifically for mining, DRL-driven dispatch systems employing double deep Q-learning within a DES framework have achieved faster decision times and greater flexibility than traditional heuristics, maintaining ore quality under stochastic operating conditions18. Experience-sharing multi-agent DRL architectures demonstrate robustness in large heterogeneous fleets, adapting to truck failures or additions without any training and increasing productivity by more than 5%19. Nevertheless, single-agent RL cannot fully cover the coordination required in multi-truck systems. This shortcoming is addressed by Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), where a combination of centralized training and decentralized execution (CTDE) is possible20.

QMIX has gained prominence in MARL algorithms due to its efficient implementation of monotonic value factorization. In QMIX, the parameters of the mixing network are generated by hyper-networks based on the global state, ensuring that improvements in the value function of any one agent will not decrease the combined value20. This structure implements the Individual-Global-Max (IGM) condition, which enables coordinated policies even in partially observable, random settings. Various extensions of QMIX have demonstrated its versatility:

-

λ-weighted double estimation QMIX reduced overestimation bias and increased convergence stability in StarCraft II micromanagement tasks21.

-

In aerial mobility, distributed QMIX makes eVTOL route planning and passenger matching more efficient22.

-

QMIX-enhanced model predictive control in vehicle platooning amid traffic changes improved lane tracking and energy efficiency23.

-

QMIX improved coverage and interference resilience in multi-UAV networks by jointly managing trajectory and communication24.

-

Grid-based area coverage achieved efficient cooperative navigation using QMIX with attention mechanisms in limited communication conditions25.

Nevertheless, QMIX is sensitive to high-dimensional state inputs and adversarial perturbations, which has led to ongoing research on policy regularization, adversarial training, and other robustness-enhancing strategies26.

Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) complement MARL through probabilistic clustering, which is capable of modeling multimodal, unstructured data distributions. GMMs identify latent structures in high-dimensional observations by fitting Gaussian components using the EM (Expectation-Maximization) algorithm, leading to interpretable and compact embeddings27,28. Applications of GMMs include fault diagnosis29hyperspectral image segmentation30anomaly detection31and industrial pattern recognition32.

The combination of QMIX and GMM results in the proposed hybrid framework that combines coordinated multi-agent learning with structured state representation. GMM-constructed embeddings reduce the dimensionality of the state-space while retaining important cluster features, which go as input to agent-specific Q-networks. These outputs are combined via QMIX’s monotonic mixing network into a global action-value function subject to the IGM constraint, which represents both effective coordination and detailed state encoding. This integration aims to increase sample efficiency, accelerate convergence speed, and improve generalization in random, high-dimensional mining environments. By leveraging the complementary strengths of MARL and probabilistic clustering, the proposed approach addresses both coordination and data representation challenges inherent to modern open-pit mining operations.

The present study, therefore, proposes to combine the strengths of QMIX and GMM to formulate a robust system for intelligent path planning and scheduling in open-pit mining. Within this proposed multi-agent framework, trucks are treated as agents, where QMIX coordinates these agents in decision-making, and GMM optimizes the state-space representation within the environment. Therefore, the objectives of the proposed QMIX-GMM-based framework in this study are:

-

1.

Improving truck scheduling in mining with integrated QMIX-GMM framework to enhance efficiency and automation of truck management, and to effectively address challenges like fluctuating road conditions, traffic congestion, and operational uncertainties in open-pit mining.

-

2.

Reducing computational complexity while maintaining decision-making efficiency in highly stochastic mining environment. We seek to improve the state-space representation making it more structured and interpretable.

-

3.

Benchmarking performance and comparative evaluation against existing approaches in terms of task completion, resources utilization, waiting time, and computational efficiency in mining truck-dispatch system.

The rest of the paper is structured as: Methodology – This section presents the working of QMIX, GMM, and QMIX-GMM. Results and discussion – This section discusses the performance of QMIX, QMIX-GMM against some other RL algorithms. Finally, conclusions of the work are presented.

Methodology

As the experiments in this paper deal with multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithms, QMIX, in conjunction with GMM, we describe the key concepts associated with its implementation. It is then followed by the introduction of the simulation environment setup as well as the algorithmic context of the work presented.

QMIX implementation for multi-agent decision-making

QMIX is a state-of-the-art multi-agent deep reinforcement learning model that has been developed to solve collaboration problems in Multi-Agent System (MAS). There is a common practice for multi-agent deep reinforcement learning, called Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE). This paradigm enables global information to be used in policy learning during epochs of training but demands each agent to base its decisions contained in a policy solely on local observations during the epoch of execution20. In environments with multiple agents, addressing collaboration issues under the CTDE paradigm involves finding the best-distributed policy to ensure that the team’s “state-joint action” value function is optimized. This challenge involves recognizing how each agent helps further the aims of the team and the manner in which these countless actions add up to give the best result.

In the context of fleet management in open-pit mining, we consider a system of multiple haul trucks \(a \in A\) collaborating to optimize their routing and scheduling. Following the decentralized partially observable Markov decision process (Dec-POMDP)20the RL-framework yields:

where, S is the state-space representation (e.g. truck locations, road conditions, load status). U is the joint action-space for trucks. \(P\left( {s'|s,u} \right)\) is transition probability function. \(r\left( {s,u} \right)\) is reward function. Z is observational space for truck’s access to partial environment data. \(O\left( {s,a} \right)\) is the observation function. n is the number of trucks in the system. γ is discount factor ensuring long-term optimization. Let \({Q_a}\) be the value function of an individual truck, then the joint action-value function, \({Q_{total}}\), learnt by QMIX is given as

where, the function f is monotonic combination,

which ensures that improving a single truck’s policy never decreases the total performance of the system. This specialty of QMIX is contrary to that of Value Decomposition Network (VDN) algorithm, where the contribution of an individual agent’s value function to the overall value function is additive33as

This linear relationship simplifies the structure of the total value but limits the VDN algorithm’s ability to extract policies, as it assumes that each agent’s contributions are independent and cumulative. In addition, this approach introduces a new challenge: non-monotonicity, complicating the assurance of an optimal solution for the distributed strategy20.

Monotonicity refers to the consistency in optimal performance between actions calculated through distributed strategies and those derived from the Q function, ensuring the coherence of the overall action-value function, \({Q_{total}}\) such that

where, \({\tau _n}\) represents the sequence of historical observations and actions, while \({u^n}\) denotes an action. If the formula does not hold, then the distributed strategy cannot maximize \({Q_{total}}\), thus failing to yield the optimal policy. This is the essence of non-monotonicity20. In the QMIX algorithm, to overcome the limitation of VDN and allow for more complex agent interactions, the partial derivatives of \({Q_{total}}\) with respect to each \({Q_i}\) are set to be non-negative.

The design objective of QMIX is to create a neural network with \({Q_i}\) as input and \({Q_{total}}\) as output, enforcing it to satisfy the monotonicity constraint specified in the equation. This enhancement in the network’s function approximation capability serves to address the shortcomings of the VDN algorithm20.

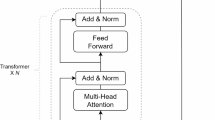

In the QMIX algorithm, \({Q_{total}}\) is represented by agent networks of n agents, a mixing network, and a set of hyper-networks, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Framework of the QMIX algorithm20.

Figure 1 shows the framework of the QMIX algorithm. Part (a) illustrates the internal structure of the mixing network, where red indicates hyper-networks that output the weights and biases for the mixing network. The blue part represents the mixing network. Part (b) displays the overall structure of the algorithm. Part (c) shows the internal structure of the agent networks.

The agent networks are composed of Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks. MLP is a type of feedforward neural network used in this architecture for feature extraction and nonlinear mapping34. The GRU neural network is a type of recurrent neural network that is used for processing sequential data, capable of passing information across time steps35. Within the Deep Recurrent Q-Network (DRQN) architecture of the QMIX algorithm, the GRU enables agents to utilize past experiences to predict the value of current actions36. The input to an individual agent’s network consists of the agent’s last actions \(u_{{t - 1}}^{a}\) and the current observational information \(O_{i}^{a}\). The output is the value function \({Q_a}\left( {{\tau ^a},{u^a}} \right)\) for a single agent at the time t, and \(h_{{t - 1}}^{a}\) and \(h_{t}^{a}\) represent the GRU hidden states at time step \(t - 1\) and t. These hidden states help the network retain past information, even when the current observation does not provide sufficient information. Symbol π represents policy function, which determines the action that the agent should take in each state. Ultimately, each agent derives a ∈-greedy policy based on the Q value, which is used for action exploration37.

The mixing network is a type of feedforward neural network that takes the outputs of the agent networks as inputs and monotonically combines them to produce\({Q_{total}}\), its function is analogous to that of a critic network. The inputs to the mixing network include the outputs from the agent networks, \(\left\{ {{Q_i}\left( {{\tau ^i},u_{t}^{i}} \right)} \right\}_{{i=1}}^{N}\), and the global state \({S_t}\) at the time t. Differing from a conventional MLP network, the weights and biases of the mixing network in the QMIX algorithm are computed by another set of networks, the hyper-networks.

Hyper-networks initialization

The input to the hyper-networks is the global state \({S_t}\), where \({w_1}\) and \({w_2}\) are hyper-networks that generate the weights for the mixing network based on the global state \({S_t}\), \({w_1}\) outputs the weights for the first layer, and \({w_2}\) outputs the weights from the hidden layer to the output layer. The terms \({b_1}\) and \({b_2}\) generate the corresponding bias terms, with \({b_1}\) providing the bias for the first layer, and \({b_2}\) providing the bias for the output layer. In the two hyper-networks \({w_1}\) and \({w_2}\), the ReLU activation function is used.

Forward propagation

The input Q value from agents’ networks and global states \({S_t}\) are first organized into a shape suitable for processing. The global state \({S_t}\) passes through \({w_1}\) to generate weights, which are then multiplied with the agent Q values, added to the bias value generated by \({b_1}\), and non-linearity is introduced via the ReLU function. After computing the hidden layer, \({w_2}\) and \({b_2}\) are used to calculate the output layer. Through matrix multiplication and addition operations, the \({Q_{total}}\) value is derived. Finally, the shape of the \({Q_{total}}\) value is adjusted to match the original batch size and time step.

Training method

Since the input to the hyper-networks is the global state \({S_t}\) and their output constitutes the parameters for the mixing network, the parameters that require training include both the hyper-network parameters and the agent network parameters20.

The training method of QMIX is an end-to-end approach that minimizes the loss function20:

where, b represents the batch size. And

where \({\theta ^ - }\) denotes the target network parameters. From this, it is evident that the training method of QMIX is similar to that of DQN38.

Therefore, the temporal difference error (TD error) can be expressed as:

\({Q_{total}}\left( {{\text{target}}} \right)\): Under the state s, it is the maximum value obtained from all actions, \({Q_{total}}\). According to the IGM (Individual Global Max) condition, the input is the maximum action-value of each agent in this state. The IGM condition is based on the premise that monotonicity holds. \({Q_{total}}\left( {{\text{evaluate}}} \right)\): Under the state s, \({Q_{total}}\) is based on the current network policy.

Mixing network update

Firstly, using the output of the current policy network and the global state s, the total \({Q_{total}}\left( {{\text{evaluate}}} \right)\) value for the current policy is calculated. The \({Q_{total}}\left( {{\text{target}}} \right)\)value is computed using the output of the target network and the global state at the next time step \(s^{\prime}\), following the formula for the target value in Q-learning. Subsequently, the TD error is calculated. Then, errors generated by padded data are filtered out through masking, and the filtered TD error is used to compute the loss function \(L\left( \theta \right)\), followed by the gradient descent (including zeroing gradients, backpropagation, gradient clipping, and finally, optimization). Throughout the training cycle, the parameters of the target network are updated at a preset interval to keep pace with changes in the policy network.

Gaussian mixture model

In mathematical terms, the GMM algorithm can be represented as follows:

where, x is a D-dimensional data point, indicating the observation which is trying to model, and \({\pi _k}\) is the mixing coefficient of the \({k^{th}}\) component. These weights satisfy the constraint \(\sum\nolimits_{{k=1}}^{K} {{\pi _k}=1}\), ensuring that the total probability distribution sums to 1. \(N\left( {x\left| {{\mu _k},{\sum _k}} \right.} \right)\) denotes the multivariate Gaussian distribution for the \({k^{th}}\) component. This distribution is characterized by its mean vector \({\mu _k}\) and covariance \({\sum _k}\), which define the shape and orientation of the Gaussian distribution in D-dimensional space. Each GMM component k is a multivariate Gaussian \(N\left( {x;{\mu _k},{\Sigma _k}} \right)\) fit to our D-dimensional state vectors (Eq. 9) and represents a latent “operational mode” in the truck dispatch process. Concretely, the component parameters \(\left\{ {{\pi _k},{\mu _k},{\Sigma _k}} \right\}\)are learned via EM and correspond to clusters in feature space (loading status, terrain type, fuel level, etc.).

In the GMM algorithm, the parameters \(\theta =\left\{ {{\pi _k},{\mu _{k,}}\sum k } \right\}_{{k=1}}^{K}\) are learned from the data using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm39. The EM algorithm is an iterative process that alternates between the following two steps:

-

1.

In the Expectation step (E-step) of the EM algorithm, we compute the posterior probabilities (or responsibilities) that each data point \({x_n}\) belongs to each Gaussian component k, given the current parameters \({\theta ^{old}}\). This calculation can be precisely represented by the following formula:

where \(\gamma \left( {{z_{nk}}} \right)\) represents the posterior probability that data point \({x_n}\) belongs to the \({k^{th}}\) Gaussian component, and \({z_{nk}}\) is a latent variable indicating the component membership of \({x_n}\). Linking each \(\left\{ {{\mu _k}} \right\}\) and \(\left\{ {{\Sigma _k}} \right\}\) to latent “operational modes” in the haul-cycle, the addition makes the representation and role of every GMM component fully transparent.

-

2.

In the maximization step (M-step) of the EM algorithm, the parameters \({\theta ^{new}}\) are updated based on the posterior probabilities computed in the E-step. The updated parameters are calculated as follows.

The new mixing coefficient for the \({k^{th}}\) component \(\left( {\pi _{k}^{{new}}} \right)\) is computed as the average of the posterior probabilities (responsibilities) \(\gamma \left( {{z_{nk}}} \right)\) for the component across all data points as:

The new mean vector for the \({k^{th}}\) Gaussian component \(\left( {\mu _{k}^{{new}}} \right)\) is calculated as the weighted average of all data points, where the weights are the posterior probabilities \(\gamma \left( {{z_{nk}}} \right)\):

The new covariance matrix for the \({k^{th}}\) Gaussian component is computed as the weighted average of the outer product of the data point deviations from the new mean, with the weights being the posterior probabilities \(\gamma \left( {{z_{nk}}} \right)\):

The EM algorithm iteratively executes the Expectation step and Maximization step until convergence is reached, meaning the change in the data’s log-likelihood under the model parameters becomes less than a predefined threshold. A principal benefit of GMMs lies in their capacity to approximate intricate, multimodal data distributions through the amalgamation of multiple Gaussian components27. This characteristic renders GMMs exceptionally appropriate for the representation of varied and indeterminate data typical in real-world settings, such as environmental observations obtained by autonomous trucks in open-pit mining contexts.

Combination of QMIX and GMM

This study introduces the integration of the GMM with the QMIX algorithm to enhance decision-making capabilities in intelligent truck scheduling systems open-pit mining environment. The approach capitalizes on the strength of GMM to uncover latent structures in both the state and action spaces of trucks, thereby significantly aiding the learning and decision-making process of QMIX by offering a more refined and informative representation of the environment.

QMIX functions by estimating the value of actions taken by individual trucks (agents) in specific states through local Q-networks. These local Q-values are combined using a mixing network to generate a global Q-value:

In this formula, S denotes the global state, \({a^n}\) indicates the action of the \({n^{th}}\) agent, \({Q_n}\) refers to the local Q-network of the \({n^{th}}\) agent, \({h^n}\) is the state embedding of the \({n^{th}}\) agent obtained through GMM, and M is the nonlinear mixing function that aggregates the local Q-values.

The training goal of QMIX is to minimize the temporal difference (TD) error as stated in Eq. (8)

The proposed method utilizes GMM to provide a compact and informative representation of the state for each agent’s local Q-network. Initially, GMM is employed to cluster the state space of trucks as follows:

Subsequently, the posterior probability of each state belonging to each cluster is determined:

These posterior probabilities form a compact state representation, which is input into a state encoder (e.g., MLP) to generate a low-dimensional embedding vector \({h_t}\):

This embedding vector \({h_t}\) replaces the original state representation as the input to each agent’s local Q-network:

.

Embedding GMM into QMIX facilitates learning and decision-making in a more compact and informative state space, enhancing sample efficiency and generalization capabilities. However, in the same manner, GMM can also be used in action space to get rid of action space dimensionality and find out which actions resemble each other.

By integrating GMM with QMIX in this way, we expect to achieve following benefits:

-

1.

Dimensionality reduction: The problem that is addressed by GMM is a critical one to be solved since it enables the learning process and the state as well as the action space to be reduced to possible manageable and efficient dimensions.

-

2.

Feature extraction: GMM can find out the hidden structure and patterns of the state and action spaces because GMM extracts more interpretable and useful features for decision-making.

-

3.

Improved sample efficiency: QMIX could potentially converge faster and at the same time, need comparatively fewer samples to have good learning and performance.

-

4.

Enhanced generalization: on this basis, through the groundbreaking GMM clustering, the QMIX can derive the compact state-action coordination and further enhance the ability to learn the strategic factorization and adapt the learned strategy to unseen scenarios.

Simulation environment setup

In this experiment, the basic environment is simulated using a grid-based graphical representation. The mining map is defined as a two-dimensional gird, where each grid unit represents a step. This setup allows every part of the map to be identified by a two-dimensional array. In the simulated mining area, the loading and unloading points are simulated as separate interaction points. Trucks are data points that can move continuously within the environment and interact with these interactions. To simulate the conditions of roads within the mining area, data cells in the mining environment will be blocked, and the remaining unblocked grids will represent the roads that are permissible for travel.

After the simulation starts, interaction points will be generated on the simulation scene based on the pre-set coordinates of loading and unloading points. Trucks, acting as agents, will randomly appear at any location on the scene but will always be on the paths. To offset the impact of the randomness of truck spawn points on the experimental results, all experiments will be conducted over sufficiently long episodes to mitigate the effects of random truck generation. The interaction logic between mining trucks and loading/unloading points is as follows: Each time a mining truck travels according to the instructions given by the algorithm and reaches a loading or unloading point, these points are accounted for with an instruction count, which increases by + 1 for any truck that arrives. All subsequent test results are calculated based on this count. For trucks, upon passing through a loading point, their states transition to “loaded”. When a “loaded” truck passes an unloading point, the unloading point’s count increases by + 1, and the truck’s state switches to “unloaded”. In this environmental simulation, trucks have only two states: “loaded” and “unloaded”. The subsequent result calculations for this experiment are determined based on the number of interactions between each loading and unloading point with the trucks, further factored into the computation.

To replicate the conditions of a real mining area more closely, this experiment incorporates a customization system. Within this system, experiments can customize aspects of the trucks such as speed, fuel consumption, and loading capacity. It is all influenced by the current state of the truck namely speed, fuel consumption as well as the capacity of loading the trucks. As mentioned previously, trucks have two states: “unloaded” and “loaded.” For each simulation, the specific speed, fuel consumption, and loading capacity of the vehicle can be predetermined.

All test results in this experiment were generated within a simulation environment developed by the research team. All test results for this experiment were generated using PyCharm and tested on a personal computer. The specifications of the computer include a 7950X CPU, a graphics card RTX 4090, and 64GB of RAM.

Results and discussion

In this section, the performance of the proposed GMM with the QMIX approach-based intelligent path planning and scheduling system of mining trucks is analyzed. The proposed methodologies are implemented in the working platform of MATLAB. Firstly, QMIX algorithm is assessed for its performance against other competitive algorithms for various parameters such as rewards, waiting time, task completion, and utilization of computational resources. Next, we present the comparative performance analysis of QMIX and proposed QMIX-GMM algorithms over several useful parameters.

Performance analysis

In this section, the performance of the QMIX approach is compared with the existing Auction-based algorithm, adaptive routing algorithm, Deep Q-Network (DQN), and Greedy algorithm.

Figure 2 shows the graphical presentation of reward analysis based on episodes. When the episode count is 30, the reward value of the proposed QMIX approach is 2425.67 and the error bar value is 45.21. For the same episode count, the existing approaches attain a lower value when compared to the proposed approach. Due to the usage of Q-learning table-based auction learning, the proposed approach achieves higher performance.

Table 1 shows the performance of the path planning and scheduling approaches based on the waiting time and task completions. Here, the proposed QMIX takes lesser waiting time when compared to the existing approaches. When the episode count is 100, the waiting time of the QMIX approach is 3.2 min; but, for the same episode count, the existing approaches take more time when contrasted with the proposed method. According to the task completion measure, the QMIX achieves higher task completion for all the episodes. The adaptive routing and the greedy approaches provide poor task completion outcomes than the other existing approaches and the proposed approaches.

The performance of the proposed approach-based planning and scheduling process of mining trucks in terms of training time and inference time is displayed in Fig. 3. Here, the training time and the inference time are varied based on the fleet size. When the fleet size is 10, the training time of the proposed approach is 0.051ms and the error value of the training process is 0.033ms. The training time is higher at fleet size 20. Similarly, the inference time is also higher at the 20th fleet size.

Figure 4 shows the latency analysis of the proposed approach-based path planning and scheduling process. The latency of the proposed approach is 3.68 ms for the fleet size of 10. The latency is varied based on the fleet size of the mining trucks.

Table 2 shows the performance of the proposed and existing methods based on the resource utilization metric. Here, the resource utilization is varied based on the episode count. For the 50th episode count, the proposed QMIX takes 92% resource utilization, which is higher than the existing methods.

Performance analysis on computational resources—QMIX and QMIX-GMM

In this experiment, the computational resources consumed by training models for different fleet sizes were investigated with QMIX and QMIX-GMM algorithms. In a multi-agent reinforcement learning environment, if the algorithm’s computing time and resource usage escalate significantly as the number of agents increases, real-time performance may be compromised, and hardware costs could become prohibitive. An effective algorithm should maintain relatively acceptable performance and resource consumption as the scale of agents grows. This controlled experiment helps identify whether the algorithm faces resource bottlenecks in large-scale scenarios.

Although conventional reinforcement learning research often emphasizes convergence speed and reward metrics, additional factors such as inference speed (i.e., the ability to make decisions within tight deadlines), CPU usage (i.e., the sufficiency of hardware resources), and memory usage (i.e., viability on resource-constrained platforms) are also critical. Figure 5 depicts the comparison of various parameters with QMIX and QMIX-GMM models.

An algorithm that performs well with fewer agents yet exhibits a steep rise in resource demands as agent numbers increase may not be suitable for large-scale applications. “Inference time” denotes the duration required for each decision-making step of the algorithm during its operational phase, as opposed to its training phase. Specifically, when provided with the current state, and GMM-QMIX or QMIX is tasked with selecting a set of actions (such as determining the next behavior of a truck), the average time spent by the model’s internal networks—including GMM feature extraction, attention modules, and mixing networks—for a single forward pass is defined as “inference time”.

Figure 5(a) illustrates the 95th percentile latency. Specifically, when all inference durations are sorted in ascending order, the value at the 95th percentile represents the threshold for the top 95% of the data. In real-time systems, this metric provides a more accurate reflection of the system’s worst-case performance under high-load conditions or during occasional anomalies.

By comparing all these data, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

GMM has lower inference time than QMIX in different scales, and as the fleet size increases, GMM-QMIX still maintains a relative advantage in inference time.

-

(2)

For small-scale fleets (5 trucks, 10 trucks), the training time of GMM-QMIX is significantly lower than that of QMIX, and the gap between the two becomes smaller when the scale is larger. However, overall, GMM-QMIX still maintains or is slightly better than the QMIX algorithm.

-

(3)

Under the worst conditions, the 95th percentile delay of GMM-QMIX is also lower than that of QMIX, indicating that GMM-QMIX still has better stability and robustness in high-load or abnormal scenarios.

-

(4)

As the fleet size increases, the CPU usage of GMM-QMIX is still lower than that of QMIX, which means that it has a smaller computational burden in the multi-agent decision-making process, is more scalable, and has a smaller memory overhead.

In summary, GMM-QMIX is superior to, or at least not inferior to QMIX in terms of inference time, worst-case delay, CPU and memory resource usage, and the advantages are more obvious in large-scale fleets.

Performance analysis with distinct levels of simulated environment—QMIX and QMIX-GMM

Three distinct levels of simulation environments are established herein, which are defined as simple environments, moderate environments and difficult environments. The difficulty of the three environments is distinguished by: terrain restrictions, truck slope restrictions, truck speed differences, and obstacle restrictions. Figure 6 provides the simplest schematic layouts for the three environment configurations—simple, moderate, and difficult.

The specific environmental design is shown in Table 3.

The comparative performance of QMIX and QMIX-GMM models for such parameters as training time, CPU usage, and memory overhead for the different levels of difficulty in simulated environments is presented in Fig. 7.

The simulation environment is designed to mimic varying driving challenges by altering key factors such as terrain, slope, and obstacles. Table 4 summarizes how these elements are configured to create different levels of difficulty. It outlines how various terrain types provide distinct road conditions, how slope effects are implicitly modeled through these terrains, and how the strategies placement of obstacles adds complexity to route planning navigation.

Based on the three graphs (for simple, medium, and difficult environments, depicted in Fig. 7), the following trends emerge:

-

1.

Training time: Under all conditions, GMM-QMIX consistently exhibits lower training time than standard QMIX. While training time increases overall as the environment becomes more complex, the gap between GMM-QMIX and QMIX also widens, demonstrating GMM-QMIX’s ability to maintain high efficiency in more challenging scenarios.

-

2.

Resource usage: In every environment, GMM-QMIX has lower CPU utilization and memory overhead compared to QMIX.

-

3.

Additional clustering step: Although GMM-QMIX includes an extra clustering step for the agent’s state inputs, this overhead is more than offset by the resulting speedup in training and decision-making, leading to a net gain in efficiency.

In summary, GMM-QMIX not only reduces training time across different complexities but also keeps CPU and memory usage in check, making it a more efficient and scalable choice than standard QMIX.

We additionally conducted comparative experiments on GMM-QMIX, QMIX, Auction, and adaptive algorithms across three difficulty levels: simple, medium, and difficult, and the results are shown in Fig. 8. The evaluation metric was the average delivery volume (ore delivered) across multiple test sets.

In the simple environment, both the adaptive and auction algorithms outperformed DRL algorithms in most test sets, providing higher delivery volumes. Compared to QMIX, GMM-QMIX exhibited inconsistent performance; it performed best in test set 1 but ranked last in test set 12. In the moderate environment, as complexity increased, the advantages of DRL algorithms became more apparent. Both GMM-QMIX and QMIX showed slightly better results than the auction and adaptive algorithms, though the differences were not substantial.

For difficult environments, the overall output of both GMM-QMIX and QMIX algorithms is located at the upper part of the graph, and the numerical distribution difference is extremely small, indicating that the overall production levels of the two algorithms are similar. GMM-QMIX shows instability between test environment 10 and test environment 12, which is related to the setting of the test environment. On these test sets, the test results of GMM-QMIX are slightly lower than those of QMIX, but the gap is not obvious. The curves of auction algorithm and adaptive algorithm have lower overall numerical values compared to GMM-QMIX and QMIX, and the gap is relatively obvious.

Despite the advantages of the GMM-QMIX algorithm in terms of computational resource and time efficiency, its performance in optimizing the operational results of agents within the environment is not significantly superior and can be slightly inferior in certain environmental configurations. This suggests that GMM-QMIX inevitably incurs a loss of detailed information during the clustering process of input states. The most significant detail loss stems from the fine-grained representation of original state information. Specifically, the GMM algorithm compresses high-dimensional states into a fixed three-dimensional probability distribution, which abstracts subtle differences in local maps, terrain, load, and fuel into “the same cluster”. When two states exhibit minor but critical differences in local observations or terrain, GMM tends to classify them as the same component. In scenarios requiring precise judgment (e.g., Set 10), this abstraction can lead to performance degradation. Additionally, if certain states occur infrequently in the data, GMM clustering may merge these rare states into larger clusters, further diminishing the algorithm’s ability to handle such special cases effectively.

In summary, the GMM algorithm does not compromise the core advantages of QMIX but rather sacrifices the fine-grained representation of high-dimensional features in the original state. The abstraction process inherent to GMM inevitably leads to a loss of some state information, which is traded for reduced computational costs. This information loss can result in performance degradation in certain extreme scenarios. However, overall, due to the high predictability of the operational states of open-pit mining trucks and their adherence to fixed operational procedures, the clustering effectiveness remains sufficiently robust, thereby limiting the impact on the primary decision-making capabilities of the strategy.

Figures 9 and 10 show the training curves for the loss over time and rewards over episodes for QMIX-GMM model, and QMIX model, respectively. Despite exhibiting a higher initial loss during the early training phase, GMM-QMIX demonstrates a rapid attenuation of loss, subsequently maintaining a consistently low and stable value. This behavior indicates superior convergence with minimal fluctuation as it approaches the optimal strategy. In contrast, although standard QMIX starts with a lower initial loss, its training process is characterized by greater fluctuations, suggesting less stable convergence compared to GMM-QMIX.

Moreover, the reward curve for GMM-QMIX rises swiftly and, despite some fluctuations in the mid-to-late stages, remains within a higher range, indicating enhanced stability and superior overall returns. While pure QMIX occasionally achieves high rewards, its larger fluctuation range undermines its overall stability relative to GMM-QMIX.

The robustness of GMM-QMIX is further evidenced by its ability to maintain a relatively consistent level of return across different training stages, thereby exhibiting a stronger resilience to uncertainties or state changes. Conversely, pure QMIX is more susceptible to extreme highs and lows, resulting in significant volatility throughout the training process and a weaker anti-interference capability.

In summary, GMM-QMIX not only achieves lower loss values and higher returns during the later training periods but also demonstrates better convergence and stability overall. Although pure QMIX benefits from a lower initial loss, its more volatile return curve and comparatively lower stability and return levels in the later stages highlight its limitations.

The environment under investigation exhibits pronounced multimodal characteristics in its state distribution, making it necessary to employ a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to reduce input dimensionality and improve computational efficiency. However, determining the optimal number of mixture components in advance poses a challenge. Too few components may fail to capture the diverse state patterns, while too many can inflate the model parameters, potentially leading to overfitting or instability during training. These drawbacks would undermine the intended benefits of using GMM to optimize the QMIX algorithm.

To address this concern, experiments were conducted to compare GMMs with three, four, and five components across various value ranges, and the results presented in Fig. 11. The analysis focused on differences in loss convergence speed, training stability, and final rewards. The findings provide a clearer basis for selecting the most suitable number of components for the current environment, thereby offering valuable guidance for subsequent parameter configurations.

In the present study, N = 3 case, the three Gaussian components learned by the EM algorithm correspond to distinct phases of the haul-cycle:

-

1.

Return empty.

-

a.

This cluster captures the “empty-run” phase where trucks, having just dumped their load, head back toward a loading point.

-

b.

Trucks in this mode exhibit low load status, moderate-to-high normalized speed, and increasing distance to the next loading location.

-

a.

-

2.

Loaded transit.

-

a.

Represents the “loaded-haul” phase: trucks fully laden with ore traveling from loading pits to dumping sites.

-

b.

Characterized by a high load status, elevated speeds, and decreasing distance to unloading points.

-

a.

-

3.

Loading/unloading dwell.

-

a.

Covers the “interaction-point dwell” when trucks are stationary or moving very slowly at loading or unloading stations.

-

b.

Defined by intermediate load values (as trucks cycle between empty and full), near-zero speed, and extended dwell time at these sites.

-

a.

These labels clarify how each Gaussian in the mixture models a real-world operational mode, providing semantic grounding for the GMM clustering in our QMIX–GMM framework.

In the early stages of training, all three configurations (N = 3, N = 4, N = 5) exhibit significant fluctuations. Overall, however, the N = 3 setting (blue curve) converges more quickly and maintains a relatively stable, lower loss range throughout the training process. By contrast, the N = 4 setting (black curve) shows more pronounced oscillations from the middle to the later stages, although its average loss remains lower than that of N = 5. Meanwhile, the N = 5 setting (red curve) experiences heightened fluctuations in the later stages of training, with a marked increase and oscillation in the 4000–5000 range, suggesting poor algorithmic stability under this hyperparameter configuration. One possible explanation is that the model becomes overly complex at N = 5, causing instability in training and leading to underfitting.

On the reward curve, the configuration with N = 3 consistently yields values within a small negative range or near zero, indicating relatively favorable returns in most training iterations. In contrast, N = 4 exhibits fluctuations during the early training phase, although it still approaches a small negative or occasionally a slightly positive reward in most rounds. For N = 5, however, there are prominently large negative rewards before 100 rounds and between 300 and 400 rounds. In some instances, the reward drops to approximately − 50,000, gradually recovering to the − 10,000 to -20,000 range in later stages (around 400 rounds). Nonetheless, it declines significantly again in the final training phase, underscoring considerable instability and extremely poor return levels.

From the training outcomes, N = 5 exhibits marked fluctuations in the loss curve, particularly a sharp decline in later stages, alongside extremely negative rewards. In contrast, N = 3 and N = 4 demonstrate more stable convergence, with rewards remaining higher or closer to positive values. This suggests that in the current mining truck dispatching environment and with the available sample size, overly complex clustering does not necessarily yield more accurate state representations. Instead, the increased complexity leads to instability. Selecting an appropriate number of components provides sufficient coverage of key environmental state patterns while minimizing the risks of overfitting and mis-training.

From an implementation standpoint, increasing the value of N necessitates estimating more component means, covariances, and mixture weights, which can substantially raise the level of training difficulty under limited data or complex distributions. Meanwhile, the quasi-online approach employed in the code allows the GMM to converge based on incoming state samples. If the noise in the resulting GMM probability distribution grows, subsequent gradient updates in the attention layer and Mixer are more likely to exhibit large-scale fluctuations. Consequently, overly large N values often lead to marked oscillations in the loss function and instability in the reward signals. When N is viewed as the number of distinct behavior or state clusters within the state space, each Gaussian component represents a primary state pattern. The distribution of these components is then employed to facilitate feature extraction in subsequent neural network layers. However, choosing an excessively large N can lead to over-clustering of the dataset, resulting in disorderly data partitioning, increased parameter dimensionality, and heightened training complexity.

Conclusions

The present study brings forth comprehensive evaluation of the GMM-QMIX framework in optimizing multi-agent truck scheduling in open-pit mining. Overcoming the limitations of the traditional methods, the multi-agent deep reinforcement learning (MADRL) has emerged as a viable solution. The following useful conclusions are drawn from this study:

-

1.

QMIX enables cooperative decision-making in multi-agent environments, while GMM effectively structures the state-space representations, reducing dimensionality and preserving critical decision-making parameters. The novel integration of QMIX and GMM framework therefore enhances decision-making efficiency by filtering the noisy environmental data, extracting meaning features, and speeding up convergence.

-

2.

A rigorous evaluation of QMIX-GMM framework against Auction-based, Adaptive Routing, Deep Q-Network (DQN), and Greedy algorithms was carried out based on several parameters – task completion rates, waiting times, CPU usage, memory overhead, and inference speed. Following was observed:

-

a.

QMIX-GMM framework outperforms tradition approaches in all tested environments, achieving higher task completion rates.

-

b.

QMIX-GMM framework results in lower waiting times for trucks, leading to better operational efficiency.

-

c.

QMIX-GMM framework results in lower CPU usage and memory overheads, requiring fewer computational resources, as compared to standalone QMIX.

-

d.

QMIX-GMM framework was found more suitable for real-time applications by demonstrating lower inference times.

-

a.

-

3.

QMIX-GMM framework was tested across three distinct mining environments – simple, moderate and difficult. In simple environments, auction-based and adaptive routing performed competitively but QMIX-GMM showed comparable results. In moderate environments, as complexity increased, both QMIX and QMIX-GMM surpassed heuristic-based methods. In difficult environment, QMIX-GMM showed slight instability in specific test environments but maintained superior performance compared to other approaches used in the study.

-

4.

QMIX-GMM framework also showed some limitations. While it offered improved efficiency, some loss of fine-grained information resulted in clustering using GMM. It was also observed that in certain high-complexity test sets, QMIX marginally outperformed QMIX-GMM framework, suggesting the need for further tuning.

Overall, the QMIX-GMM framework offered a significant advancement in AI-driven truck scheduling in open-pit mining, by enhancing decision-making, improving scalability, and reducing computational costs compared to the existing methods. Future improvements can be made in (1) optimizing GMM clustering to reduce information loss, (2) enhancing rewards structures in extreme conditions, and (3) implementing real-world testing to validate effectiveness in active mining operations. The limitation has been with regard to the maximum fleet size considered in the study being suitable to small or mid-scale mines.

Data availability

Data is made available with the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

All code used to produce these results are available at https://github.com/Xx143-xx/GMM-QMIX.

Abbreviations

- CTDE:

-

Centralized training distributed execution

- DES:

-

Discrete event simulation

- DQN:

-

Deep Q-network

- DRL:

-

Deep reinforcement learning

- DRQN:

-

Deep recurrent Q-network

- EM:

-

Expectation-maximization

- eVTOL:

-

Electrical vertical take-off landing

- GMM:

-

Gaussian mixture model

- GRU:

-

Gated recurrent unit

- IGM:

-

Individual global max

- IQL:

-

Independent Q-learning

- JAVF:

-

Joint action-value function

- MADRL:

-

Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning

- MARL:

-

Multi-agent reinforcement learning

- MAS:

-

Multi-agent system

- MDP:

-

Markov decision process

- MLP:

-

Multi-layer perceptron

- MPC:

-

Model predictive control

- POMDP:

-

Partially observable Markov decision process

- RL:

-

Reinforcement learning

- TD:

-

Temporal difference

- UAV:

-

Unmanned aerial vehicle

- VDN:

-

Value decomposition network

References

Huang, Y. et al. Q-learning assisted multi-objective evolutionary optimization for low-carbon scheduling of open-pit mine trucks. Swarm Evol Comput 92, 101778 (2025).

Chaowasakoo, P., Seppälä, H., Koivo, H. & Zhou, Q. Improving fleet management in mines: the benefit of heterogeneous match factor. Eur J Oper Res 261, 1052–1065 (2017).

Wang, Q., Gu, Q., Li, X. & Xiong, N. Comprehensive overview: fleet management drives green and climate-smart open pit mine. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 189, 113942 (2024).

Hazrathosseini, A. & Moradi Afrapoli, A. Transition to intelligent fleet management systems in open pit mines: A critical review on application of reinforcement-learning-based systems. Mining Technology: Transactions of the Institutions of Mining and Metallurgy 133, 50–73 (2024).

Zhang, L. & Xia, X. An integer programming approach for Truck-Shovel dispatching problem in Open-Pit mines. Energy Procedia 75, 1779–1784 (2015).

Chang, Y., Ren, H. & Wang, S. Modelling and optimizing an open-pit truck scheduling problem. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2015, 745378 (2015).

Temeng, V. A., Otuonye, F. O. & Frendewey, J. O . A Nonpreemptive Goal Programming Approach to Truck Dispatching in Open Pit Mines. Vol. 7. 59–67 (2012) https://doi.org/10.1142/S0950609898000092.

Upadhyay, S. P. & Askari-Nasab, H. Truck-shovel allocation optimisation: a goal programming approach. Mining Technology 125, 82–92 (2016).

Moradi-Afrapoli, A. & Askari-Nasab, H. A stochastic integrated simulation and mixed integer linear programming optimisation framework for truck dispatching problem in surface mines. Int J Min Miner Eng 11, 257–284 (2020).

Moradi Afrapoli, A. & Askari-Nasab, H. Mining fleet management systems: a review of models and algorithms. Int J Min Reclam Environ 33, 42–60 (2019).

Mohtasham, M., Mirzaei-Nasirabad, H., Askari-Nasab, H. & Alizadeh, B. Multi-stage optimization framework for the real-time truck decision problem in open-pit mines: a case study on Sungun copper mine. Int J Min Reclam Environ 36, 461–491 (2022).

Hazrathosseini, A. & Moradi Afrapoli, A. The advent of digital twins in surface mining: its time has finally arrived. Resources Policy 80, 103155 (2023).

Qin, Z. et al. Ride-Hailing order dispatching at DiDi via reinforcement learning. 50, 272–286 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.2020.1047.

Lee, J., Lee, K. & Moon, I. A reinforcement learning approach for multi-fleet aircraft recovery under airline disruption. Appl Soft Comput 129, 109556 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Scheduling optimization of electric ready mixed concrete vehicles using an improved model-based reinforcement learning. Autom Constr 160, 105308 (2024).

Haydari, A. & Yilmaz, Y. Deep reinforcement learning for intelligent transportation systems: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 23, 11–32 (2022).

Jin, J., Cui, T., Bai, R. & Qu, R. Container Port truck dispatching optimization using Real2Sim based deep reinforcement learning. Eur J Oper Res 315, 161–175 (2024).

Noriega, R., Pourrahimian, Y. & Askari-Nasab, H. Deep reinforcement learning based real-time open-pit mining truck dispatching system. Comput Oper Res 173, 106815 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. Dynamic dispatching for large-scale heterogeneous fleet via multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings – 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Big Data 2020. 1436–1441. https://doi.org/10.1109/BIGDATA50022.2020.9378191 (2020).

Rashid, T. et al. Monotonic value function factorisation for deep Multi-Agent reinforcement learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research 21, 1–51 (2020).

Zhao, L. Y. et al. An overestimation reduction method based on the Multi-step weighted double Estimation using Value-Decomposition Multi-agent reinforcement learning. Neural Process Lett 56, 1–21 (2024).

Yun, W. J., Jung, S., Kim, J. & Kim, J. H. Distributed deep reinforcement learning for autonomous aerial eVTOL mobility in drone taxi applications. ICT Express 7, 1–4 (2021).

Zhang, S. & Zhuan, X. Distributed model predictive control for two-dimensional electric vehicle platoon based on QMIX algorithm. Symmetry 14, 2069 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. Joint UAV trajectory and communication design with heterogeneous multi-agent reinforcement learning. Science China Information Sciences 67, 1–21 (2024).

Yuan, G. et al. Multi-agent cooperative area coverage: A two-stage planning approach based on reinforcement learning. Inf. Sci. (N Y) 678, 121025 (2024).

Guo, W., Liu, G., Zhou, Z., Wang, L. & Wang, J. Enhancing the robustness of QMIX against state-adversarial attacks. Neurocomputing 572, 127191 (2024).

Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, 2006. (Springer, 2016).

Reynolds, D. Gaussian mixture models. In Encyclopedia of Biometrics. 659–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73003-5_196 (2009) .

Qiu, X. et al. Fault diagnosis for multi-axis carving machine systems with Gaussian mixture hidden Markov models: A data-model interactive perspective. Control Eng. Pract. 154, 106163 (2025).

Kartakoullis, A., Caporaso, N., Whitworth, M. B. & Fisk, I. D. Gaussian mixture model clustering allows accurate semantic image segmentation of wheat kernels from near-infrared hyperspectral images. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 259, 105341 (2025).

Chen, Q. & Sang, L. Face-mask recognition for fraud prevention using Gaussian mixture model. J Vis Commun Image Represent 55, 795–801 (2018).

Yu, J. Pattern recognition of manufacturing process signals using Gaussian mixture models-based recognition systems. Comput Ind Eng 61, 881–890 (2011).

Sunehag DeepMind, P. et al. Value-Decomposition Networks for Cooperative Multi-Agent Learning. (2017).

Lerner, B., Guterman, H., Aladjem, M., Dinstein, I. & Romem, Y. Feature extraction by neural network nonlinear mapping for pattern classification. In Proceedings - International Conference on Pattern Recognition. Vol. 4. 320–324 (1996).

Dey, R. & Salemt, F. M. Gate-variants of Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) neural networks. In Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems 2017-August. 1597–1600 (2017).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement Learning : An Introduction. Vol. 526 (2018).

Zhang, R. et al. Optimistic ε-Greedy Exploration for Cooperative Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. (2025).

Van Hasselt, H., Guez, A. & Silver, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning with Double Q-learning. In 30th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2016. 2094–2100 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v30i1.10295.

Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M. & Rubin, D. B. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 39, 1–22 (1977).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Danqi Li: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xiaolei Xiang: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Wei Lin: Re-writing, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, X., Lin, W. & Li, D. A hybrid MARL clustering framework for real time open pit mine truck scheduling. Sci Rep 15, 34875 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16347-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16347-0