Abstract

The optimal endovascular strategy for acute symptomatic isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion (sICAO) management remains unclear because of the anatomical complexity and high risk of distal embolization. This study looks into the safety, effectiveness, and outcomes of a novel Aspiration-Based Dual-Protection Strategy Under Proximal Balloon Occlusion and Distal Embolic Protection Device (ABGCEPD) for sICAO treatment. This retrospective study involved 65 patients with acute moderate-to-severe stroke who underwent endovascular treatment using ABGCEPD at three hospitals in China between January 2016 and December 2023. The primary outcome included successful reperfusion, defined as a modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction score ≥ 2b. A good outcome at discharge was defined as a modified 3-month Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0 to 2 at 90 days. Secondary outcomes included mortality, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), and embolization to new territories (ENT). All 65 patients with sICAO were treated using ABGCEPD. The rate of successful reperfusion (modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction score ≥ T2b) was 92.9%, with a good clinical outcome attained by 60% of patients (90-day mRS 0–2). The incidence of sICH was 10.7%, mortality was 7.1%, and ENT was 7.0%. ABGCEPD is a feasible, safe, and efficient method for acute sICAO management. It may decrease the incidence of distal embolization during endovascular treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endovascular treatment (EVT) has emerged as the standard treatment for patients with acute large vessel occlusive stroke1. Symptomatic isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion (sICAO) is defined as follows: (1) acute ischemic stroke symptoms attributable to internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score ≥ 6 and (2) angiographic confirmation of isolated occlusion at the cervical ICA segment (C1) without tandem intracranial occlusions. However, the optimal management strategy for sICAO remains undefined2.

sICAO accounts for 3–11% of large vessel occlusions3. sICAO is associated with high mortality (12%), progressive stroke (7–8%), early neurological deterioration (22–31%), and poor functional outcomes (modified Rankin Scale score, mRS > 3 in 67% of patients)4. A comprehensive review of the existing literature indicates that EVT is the optimal treatment option for sICAO5,6,7.

Despite the superiority of EVT over other treatment modalities, concerns persist regarding technical risks associated with crossing ICA lesions (including vessel dissections and distal embolization), which have impeded its widespread implementation8. Distal embolization occurs in 18–22% of EVT cases and is closely associated with an unfavorable long-term prognosis3,9. This necessitates advancing EVT techniques to minimize the risks of distal embolization10.

Existing strategies include proximal balloon guide catheters (that facilitate flow reversal) and distal embolic protection devices (EPD), both of which reduce new embolus formation through mechanical interception and negative-pressure aspiration11,12. However, relying on a distal EPD alone may be insufficient in complex lesions or hemodynamically unstable scenarios..

To this end, this study proposes a novel Aspiration-Based Dual-Protection Strategy Under Proximal Balloon Occlusion and Distal Embolic Protection Device (ABGCEPD), which integrates proximal flow arrest with distal embolic capture to reduce embolic escape during EVT.

This retrospective study looks into the safety and efficacy of ABGCEPD in sICAO management to optimize EVT strategies for high-risk patients..

Methods

Patients

This study was conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the institutional review board and adhered to its ethical guidelines(the ethics committee of Huanhu Hospital Affiliated to Tianjin Medical University, 202501221500000278505). Patients with acute ischemic strokes caused by large vessel occlusion were selected using the prospective endovascular stroke registry, which has been established since January 2016. The inclusion criteria were as follows: The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) initial NIHSS score ≥ 6; (3) an mRS score of 0 or 1 before the stroke; and (4) presence of isolated ICAO. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) minor stroke with NIHSS score < 6; (2) occlusion of the middle cerebral artery, anterior cerebral artery, or posterior circulation; (3) tandem occlusion; (4) other non-cervical ICA occlusion; and (5) missing clinical data.

Before intervention, all patients underwent a multimodal imaging examination that included:

-

(1)

Angiographically confirmed isolated ICA occlusion or noninvasive imaging (CTA/MRA), without concomitant intracranial LVO (MCA M1/M2, ACA A1/A2, or posterior circulation) or Internal Carotid Artery Dissection (ICAD).

-

(2)

Clinical screening: Excluded patients with recent neck trauma, hyperextension injury, or fluctuating symptoms suggestive of arterial dissection.

Furthermore, patients presenting 6 to 24 h after the onset of symptoms were included if the infarction volume determined by multimodal magnetic resonance imaging was < 70 mL and the stroke etiology was determined to be hypoperfusion13.

Overall, 65 patients (6.9%) were enrolled in this study.

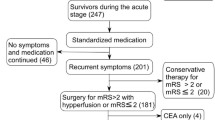

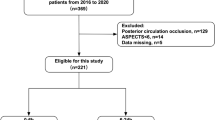

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of patient selection.

Endovascular Treatment: ABGCEPD.

ABGCEPD (Fig. 2) was conducted after obtaining informed consent from the patients or their family members. The process was conducted as follows:

-

1.

A 9 F arterial sheath was inserted into the femoral artery, and a 5 F guide catheter (Envoy; Raynham, Massachusetts, USA) was advanced. Diagnostic angiography was conducted to identify the cerebral vasculature and confirm major vessel occlusion (Fig. 2A).

-

2.

A 0.014-inch microwire (Transcend; Stryker, Michigan, USA) was passed through a microcatheter (MicroVention; Tustin, California, USA) to traverse the occlusion. Simultaneously, a 9 F Balloon guide catheter (Stryker, Bayside Parkway, Fremont, USA) was inflated to obstruct the proximal blood flow.

-

3.

The occlusion site was delineated by injecting a small quantity of contrast agent through the microcatheter (Fig. 2B).

-

4.

Using the exchange procedure along the microguidewire, the microcatheter and microguidewire were removed. A distal embolic protection device (Spider FX; Medtronic) was inserted in the petrous segment of the ICA to prevent a big thrombus from exiting the carotid artery distally (Fig. 2C).

-

5.

Balloon angioplasty was conducted at the occluded vessel using a Lite PAC 5*30 balloon, inflated to 5 to 6 atmospheres to reopen the vessel and create an endovascular path. The balloon guide catheter (BGC) remained inflated, and the distal EPD was deployed (Fig. 2D).

-

6.

Continuous aspiration was applied using a large-bore catheter under negative pressure suction (Fig. 2E). Subsequently, the BCG and EPD were retrieved.

-

7.

Residual thrombus from the ICA was aspirated using the large-bore catheter (Fig. 2F).

-

8.

A DynaCT scan was conducted to examine the patient’s vascular status and collateral circulation. Based on the findings, a carotid artery stent was implanted under proximal occlusion14 (Fig. 2H).

The following measures are adopted in real-world clinical practice:

-

1.

Temporary occlusion using a proximal BCG.

-

2.

Continuous aspiration using a large-bore catheter.

-

3.

Distal vessel protection using an EPD (Fig. 3).

A schematic diagram of the ABGCEPD technique. (A) Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) shows isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion. (B) Inflating BGC to occlude the proximal blood flow, a microcatheter traveling through the occlusion site with the assistance of a microwire. (C) An embolic protection device was advanced into the distal cervical segment of the ICA over the microwire. (D) Balloon angioplasty of the initial ICA segment. (E) The BGC is advanced to the bulb portion to secure ICA flow arrest. (E) After removing the angioplasty balloon, continuous aspiration can be performed until there is profuse backflow through the occluded BGC. (F) Inflate the BGC to occlude proximal blood flow while continuous aspiration throughout the procedure using large-bore catheter. (G) Using the BGC to occlude proximal blood flow, and then an internal carotid artery stent is inserted.

A 65-year-old male patient presented with the left carotid artery occlusion. (A,B) Angiography revealed occlusion of symptomatic cervical internal carotid artery (sICAO). (C) BGC was inflated to block proximal blood flow, and a microcatheter was advanced over a microwire across the occluded segment into the true lumen. (C) Using an exchange technique, a distal EPD was deployed in the petrous segment of the internal carotid artery. (D) Balloon angioplasty was used to open the blocked area, creating a endovascular pathway. (E) After establishing the endovascular pathway, the distal EPD was retrieved under negative pressure. (F) BGC was inflated to block proximal blood flow while the large-bore catheter continued to aspirate residual thrombus from the carotid artery. (G) BGC was utilized to occlude proximal blood flow during the deployment of the carotid artery stent. (H) Post-stenting angiography demonstrated complete vascular recanalization, indicating that the stent had been successfully released.

Plain technique

Previously, distal EPD have been widely used to prevent embolism escape.In this research, the mentioned approach is known as the “plain technique”10,15,16. Unlike ABGCEPD, the plain technique depends solely on the development of a distal EPD to prevent distal embolization (Fig. 4). The clinical outcomes of these three studies are detailed in Table 1.

The patient selection criteria for these three studies were as follows:

-

1.

Age ≥ 18 years with pre-stroke mRS score ≤ 1.

-

2.

Moderate-to-severe neurological deficits (NIHSS ≥ 6).

-

3.

Angiographically confirmed isolated ICA occlusion or noninvasive imaging (CTA/MRA), without concomitant intracranial LVO (MCA M1/M2, ACA A1/A2, or posterior circulation).

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Minor stroke (NIHSS < 6).

-

2.

Non-isolated occlusions:

-

Tandem occlusions (ICAO + intracranial LVO);

-

T-shaped/L-shaped occlusions;

-

Occlusions originating at petrous/cavernous segments with normal cervical ICA.

-

-

3.

Non-availability of clinical data.

It is consistent with the enrollment criteria of our study. Ultimately, these three studies met the criteria and enrolled a total of 218 cases, collectively referred to as the Plain Technique. They served as the control group for comparison with our research.

Clinical assessment and characteristics of cases

Three neurologists, each with ≥ 5 years of fellowship training in neuroimaging, independently assessed the imaging data. These assessments were conducted in a blinded manner, without access to the patient’s data. After the endovascular procedure, a radiographic assessment of cerebral reperfusion was conducted using the modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction scale (mTICI)17,18. An mTICI score of 2b or 3 indicates successful reperfusion19.

All pre- and post-treatment clinical data were retrospectively obtained from patients’ medical records and documented using standardized forms (Table 2). The following variables were included:

-

Demographics: age and sex.

-

Stroke characteristics: average onset-to-admission time (h), NIHSS score (median), and Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS).

-

Process metrics: average time from admission to puncture procedure (min), time from groin puncture to reperfusion (min), and occlusion site.

-

Medical history: smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and atrial fibrillation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 23.0; Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed, or as median with interquartile range (IQR) or range if non-normally distributed. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Baseline characteristics between the ABGCEPD group and the Plain Technique group were compared using independent samples t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests (for expected cell counts < 5) for categorical variables. Primary and secondary outcomes (reperfusion success, good clinical outcome, mortality, sICH, ENT rates) were compared between the two treatment groups using Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to quantify the association between treatment group and outcomes. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

The database includes 935 patients who received endovascular treatment between January 2016 and December 2023. Of them, 65 patients were identified as having sICAO and were included in this study (Table 2). Among the selected patients, 49 (75%) were men. The average age was 64 ± 7 years, and the average onset-to-admission time was 14 ± 5 h. The average NIHSS score was 11 (8–13) before the procedure. The average time from hospital admission to groin puncture was 74 ± 30 min, and the average time from groin puncture to reperfusion was 126 min. The average ASPECTS was 7.0 (6.0–8.0). Of all patients, 67.9% were smokers, 32.1% had diabetes mellitus, 17.9% had idiopathic atrial fibrillation, and 75% had hypertension.

Treatment outcomes and complications are summarized in Table 3. Successful reperfusion was achieved in 92.9% of patients (mTICI ≥ T2b), and the first-pass recanalization rate was 64.3%. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was 10.7%, whereas embolization to new territories (ENT) was observed in 7% of patients. Arterial dissection was observed in 5% of patients; vessel perforation was not observed. The mortality was 7.1%. Good clinical outcomes were achieved in 60% of patients (90-day mRS 0–2).

Three prior studies that utilized only distal EPD reported differing incidences of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH), good clinical outcomes, mortality, recanalization rates, and ENT incidence (Table 1). In contrast, the present study integrated proximal BGC with distal EPDs (i.e., ABGCEPD). These results demonstrate comparable rates of good clinical outcomes and recanalization, compared with previous studies. Nonetheless, the ENT incidence were significantly lower in the present study. The incidence of sICH was moderately higher than in previous studies (Table 1).

We have provided the baseline clinical data for the ABGCEPD group and the Plain Technique group and conducted statistical analyses, confirming that the two groups of patients were comparable in key baseline variables (age, NIHSS score, ASPECTS score, history of hypertension, history of diabetes mellitus, site of internal carotid artery occlusion). This indicates that the two groups were well-matched in terms of stroke severity, imaging findings, and underlying diseases. However, potential biases regarding gender and smoking history should be noted (Table 4).

Clinical outcomes were compared between patients treated with ABGCEPD and patients treated using the plain technique (i.e., distal EPD alone). No significant differences were observed between these two groups:

-

Good clinical outcome rate (60% vs. 58.1%, P = 0.491).

-

Mortality (7.1% vs. 13.6%, P = 0.194).

-

Recanalization rate (92.9% vs. 89.8%, P = 0.824).

However, the incidence of ENT was significantly lower in the ABGCEPD group than in the plain technique group (7% vs. 19.6%, P = 0.012). Although the ABGCEPD group demonstrated a higher incidence of sICH (10.7% vs. 5%, P = 0.037), no significant difference was observed in the good clinical outcome rate between the two groups (Table 5).

Therefore, ABGCEPD is a feasible, safe, and efficient method for acute sICAO management. It decreases the incidence of ENT, which aligns with the dual-protection mechanism underlying this technique.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the clinical application of ABGCEPD in treating acute sICAO. ABGCEPD demonstrated a high recanalization rate of 92.9%, which is comparable to the rates achieved by contemporary EVT protocols for sICAO (82–92%)10,15,16. Additionally, the incidence of ENT in the ABGCEPD group was lower than that in the plain technique group (7% vs. 19.6%, P = 0.012) (Table 4). This reduction in ENT is critical because distal embolism is a major complication of EVT and is closely associated with adverse long-term outcomes3,4.

These results indicate that ABGCEPD combines continuous aspiration with dual protection via proximal balloon-guided catheter occlusion and distal embolic protection, thus effectively reducing the risk of distal embolism and enhancing patient outcomes. These mechanisms ensure safe thrombus removal under negative pressure, thus minimizing the risk of residual thrombi from entering the intracranial circulation. Without this dual protection strategy, the risk of distal embolism may increase significantly, leading to severe complications and worse clinical outcomes20.

In this study, the rate of sICH was 10.7%, which may be attributed to the use of dual antiplatelet therapy after carotid stenting and hyperperfusion syndrome that follows recanalization, particularly in patients with large acute infarcts21. Strict postoperative blood pressure control may mitigate this complication22. However, no significant difference in favorable clinical outcomes between the ABGCEPD and plain technique groups was observed. Therefore, ABGCEPD remains clinically beneficial, despite a moderately higher sICH rate.

For distal embolism assessment, this study employed a comprehensive evaluation strategy incorporating intraoperative and postoperative monitoring. This included digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and immediate postoperative cranial CT/MRI (within 24 h). Upon detection of distal emboli, immediate adjunctive mechanical thrombectomy or intra-arterial thrombolysis was initiated to mitigate adverse effects on prognosis. In this study, the ENT rate was 7%, with approximately four cases developing thrombus escape: two migrated to the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery (MCA), one to the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA), and one to the M3 segment of the MCA. All such cases underwent prompt mechanical thrombectomy and intra-arterial thrombolysis. After timely intervention, the thrombus that escaped distally was ensured to be cleared promptly.

Notably, this study focused on acute stroke management caused by sICAO. ABGCEPD was specifically designed to address the challenges in treating acute sICAO-related stroke. These findings offer actionable guidance for clinical decision-making in acute sICAO-related stroke management.

This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size, extracted from the prospective registries of three hospitals, limits the strength of statistical analysis. Thus, multivariable regression analysis could not be conducted. Secondly, the retrospective design may have introduced operator selection bias. To mitigate this, indicator factors were defined to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ABGCEPD, including Recanalization, First-pass recanalization, symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH), Mortality, emboliazation to new territories (ENT), and a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0–2 at 90 days.Finally, the non-randomized research nature restricts the generalizability of these findings. To this end, future research should focus on large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trials to provide more robust evidence.

In conclusion, ABGCEPD is a feasible, safe, and efficient method for acute sICAO management. The continuous aspiration technique plays a crucial role in reducing the risk of distal embolization. ABGCEPD should be considered as a viable treatment modality for patients with sICAO to improve clinical outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BGC:

-

Balloon guide catheter

- EPD:

-

Embolic protection device

- ABGCEPD:

-

Aspiration-based dual-protection strategy under proximal balloon occlusion and distal embolic protection device

- sICAO:

-

Symptomatic isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin scale

- mTICI:

-

Modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction

- sICH:

-

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage

- ENT:

-

Embolization to new territories

References

Jadhav, A. P. et al. Emergent management of carotid artery occlusion in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 50, 428–433 (2019).

Kargiotis, O. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion s: a narrative review. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 15, 1–17 (2022).

Mokin, M., Kass-Hout, T., Kass-Hout, O., Dumont, T. M. & Kan, P. Snyder etc. Intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke with internal carotid artery occlusion: A systematic review of clinical outcomes. Stroke 43, 2362–2368 (2012).

Burke, M. J. et al. Short-term outcomes after symptomatic internal carotid artery occlusion. Stroke 42, 2419–2424 (2011).

Paciaroni, M. et al. Systemic thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke and internal carotid artery occlusion: the ICARO study. Stroke 43, 125–130 (2012).

Hong, J. H. et al. Endovascular treatment in patients with persistent internal carotid artery occlusion after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: a clinical effectiveness study. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 42, 387–394 (2016).

Romoli, M. et al. Reperfusion strategies in stroke due to isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion:systematic review and treatment comparison. Neurol. Sci. 42, 2301–2308 (2021).

Baik, S. K. et al. What is the real risk of dislodging thrombi during endovascular revascularization of a proximal internal carotid artery occlusion?? Neurosurgery 68, 1084–1091 (2011).

Khazaal, O. et al. Early neurologic deterioration with symptomatic isolated internal carotid artery occlusion: A cohort study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. SVIN 2, e000219 (2022).

Jadhav, A. et al. Angioplasty and stenting for symptomatic extracranial non-tandem internal carotid artery occlusion. J. NeuroIntervent. Surg. 10, 1155–1160 (2018).

Bijuklic, K. et al. The PROFI study (Prevention of cerebral embolization by proximal balloon occlusion compared to filter protection during carotid artery Stenting): a prospective randomized trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59, 1383–1389 (2012).

Thki, T. et al. Efficacy of a proximal occlusion catheter with reversal of flow in the prevention of embolic events during carotid artery stenting: an experimental analysis. J. Vasc. Surg. 33, 504–509 (2001).

Okumura, E. et al. Outcomes of endovascular thrombectomy performed 6-24 h after acute stroke from extracranial internal carotid artery occlusion. Neurol. Med. Chir. 59, 337–343 (2019).

Yi, H. J., Lee, D. H. & Sung, J. H. Comparison of FlowGate2 and merci as balloon guide catheters used in mechanical thrombectomies for stroke intervention. Exp. Ther. Med. 20, 1129–1136 (2020).

Ter Schiphorst, A. et al. Endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke due to isolated internal carotid artery occlusion: ETIS registry data analysis. J. Neurol. 269, 4383–4395 (2022).

Ni, H. et al. Endovascular treatment for acute ischaemic stroke caused by isolated internal carotid artery occlusion: treatment strategies, outcomes, and prognostic factors. Clin. Radiol. 78, 451–458 (2023).

Zaidat, O. O. et al. Recommendations on angiographic revascularisation grading standards for acute ischemic stroke: a consensus statement. Stroke. 44, 2650–2663 (2013).

Cohen, J. E. et al. Extracranial carotid artery stenting followed by intracranial stent-based thrombectomy for acute tandem occlusive disease. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 7, 412–417 (2015).

Mpotsaris, A., Bussmeyer, M., Buchner, H. & Weber, W. Clinical outcome of neurointerventional emergency treatment of extra-or intracranial carotid artery occlusions in acute major stroke: anterograde approach with Wallstent and solitaire stent retriever. Clin. Neuroradiol. 23, 207–215 (2013).

Vidale, S., Romoli, M., Consoli, D. & Agostoni, E. C. Bridging versus direct mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: A subgroup pooled Meta-Analysis for time of intervention, eligibility, and study design. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 24, 1–10 (2020).

Lockau, H. et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in carotid artery occlusion: procedural considerations and clinical results. Neuroradiology 57, 589–598 (2015).

Tsivgoulis, G., Katsanos, A. H. & Schellinger, P. D. etc.Successful reperfusion with intravenous thrombolysis preceding mechanical thrombectomy in large-vessel occlusions. Stroke 49, 232–235 (2018).

Acknowledgements

1. National Health Commission Capacity Building and Continuing Education Center Nervous System and Minimally Invasive Intervention Program. No. GWJJ20221001062. 2. Tianjin Health Science and Technology Project. No. TJWJ2024ZD0063. 3. Tianjin Key Medical Discipline(Specialty) Construction Project. 4. Tianjin Health Science and Technology Project Key Discipline Special Project (TJWJ2022XK031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.W. Data curation: S.W. Formal analysis: J.L. Funding acquisition: H.Y. and M.W. Investigation: J.L. Methodology: H.Y. Project administration: Y.S. and Y.Z. Resources: M.W. Supervision: J.L. Validation: S.W. Visualization: Y.S. Writing-original draft: J.L. Writing-review and editing: H.Y.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Wang, S., Shen, Y. et al. ABGCEPD for acute symptomatic isolated cervical internal carotid artery occlusion to improve reperfusion and reduce distal embolization. Sci Rep 15, 30377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16491-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16491-7