Abstract

Knallgas bacteria, including Cupriavidus necator H16, are promising cell factories for converting CO2 into high-value compounds under autotrophic conditions. C. necator H16 synthesizes polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), a class of biodegradable plastics. However, the trade-off between cell proliferation and PHA production often limits productivity as a result of competition for cellular resources. Real-time monitoring of both processes is crucial for optimizing this balance. However, optical density (OD), a conventional metric for monitoring proliferation, is unreliable in organisms that accumulate intracellular products such as PHA. Traditional methods such as chromatography require complex sample preparation and are not suitable for real-time analysis. This study demonstrated that the cell counts and volume measured using a Coulter counter are reliable indicators of proliferation and PHA production. This approach enables rapid and accurate monitoring and supports the optimization of material production through microbial fermentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria (Knallgas bacteria) are microorganisms that grow under aerobic conditions, using carbon dioxide (CO2) as a carbon source and hydrogen (H₂) as an energy source1. These bacteria have been explored for their potential in the CO₂-derived production of biofuels, pharmaceutical precursors, and food additives2,3,4. Among these, Cupriavidus necator H16 (formerly Ralstonia eutropha H16) has garnered significant attention because of its ability to produce polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), particularly under nutrient-depleted conditions5,6. PHA is a promising, biodegradable, and sustainable alternative to petroleum-based plastics7,8,9,10. C. necator H16 can produce high levels of PHA under specific conditions (> 80% of its cell dry weight) and has been genetically engineered for industrial-scale PHA production under autotrophic conditions11,12. Therefore, CO₂-derived biodegradable plastics are at the forefront of biotechnology.

One of the main challenges in microbial production is the trade-off between cell proliferation and product formation. Since both processes draw from the same pool of metabolic resources, optimizing their balance is essential for maximizing overall productivity13,14. Achieving this balance is key to improving the efficiency and yield of industrial bioprocesses. To determine the optimal balance, it is necessary to accurately and continuously monitor parameters related to cell proliferation and material production throughout the culture process, ideally in real time. Real-time data enable rational, data-driven regulation of gene expression and cultivation conditions, such as oxygen supply and nutrient concentration, allowing dynamic adjustments that enhance productivity.

However, obtaining reliable real-time data on cell proliferation and product formation remains challenging. Although optical density (OD) is a common method for monitoring cell proliferation by measuring light scattering from suspended microbial cells, OD and cell concentration do not always correlate. This discrepancy arises because OD is influenced by various factors, including changes in intracellular structure and cell size during growth15. This limitation is particularly relevant for C. necator H16, which accumulates the intracellular storage polymer PHA. Cell biomass is typically measured gravimetrically after lyophilizing, and quantification of intracellular PHA is usually performed using gas chromatography (GC), which lacks real-time capability16. GC, commonly used for PHA quantification, requires time-consuming sample preparation, including cell drying and methanolysis. Furthermore, hazardous chemicals, such as chloroform, methanol, and sulfuric acid, are required for the methanolysis step. These limitations highlight the need for safer and faster methods to assess cell proliferation and product formation in real time.

In this study, we propose that cell counts and cell volumes are reliable indicators of cell proliferation and the production of intracellular storage compounds, such as PHA. These metrics can be measured quickly and simultaneously using Coulter counters. A mutant strain with high PHA production was evaluated to further demonstrate the applicability of this method for optimizing PHA yield. This study presents an efficient approach to simultaneously assess cell proliferation and intracellular material production, supporting efforts to enhance biodegradable plastic production under autotrophic conditions using C. necator H16.

Results

Growth curves based on cell count and OD

Cell number and OD were continuously measured to monitor the growth of C. necator H16 in autotrophic cultures. The cells were cultivated under nitrogen-depleted conditions to induce PHA production, with ammonium ions in the culture medium depleted during the cultivation process. The OD values, measured by spectrophotometry, were compared with the cell counts obtained using a Coulter counter. The accuracy of the Coulter counter measurements for this bacterium was validated by cross-measurement with a hemocytometer, and similar growth curves and a positive correlation were obtained (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). When the growth curves based on OD and cell counts were superimposed (Fig. 1A), they were closely aligned for up to 36 h. However, after 36 h, the OD values continued to increase, although the cell counts stopped increasing. The cell count is plotted against the OD in Fig. 1B. The data were divided into two groups: plots up to 36 h (Fig. 1C) and plots after 48 h (Fig. 1D). For data up to 36 h, a strong positive correlation was observed between OD and cell count, whereas the correlation declined significantly after 36 h. To assess whether the relationship between OD and cell count differed significantly before and after 36 h, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare two models: a regression line model distinguishing the two groups (residual sum of squares = 85.06, degrees of freedom = 40) and a single regression line model without group distinctions (residual sum of squares = 184.70, degrees of freedom = 42). The regression line model that accounted for group effects demonstrated significantly better explanatory power (F = 23.43, p < 0.001). The difference in the residual sum of squares (99.64) confirms the improvement provided by the incorporation of group effects and interactions. This result indicates a significant change in the relationship between OD and cell count after 36 h. The shift observed after 36 h corresponds to the depletion of ammonium ions, as confirmed by time-course quantification (Fig. 2F), marking the onset of nutrient limitation and the initiation of PHA synthesis. Although OD serves as a reliable indicator of cell proliferation during the early stages of culture, it becomes an unreliable metric for estimating cell density after 36 h, owing to changes in cellular characteristics or composition.

Cell proliferation assessment based on the optical density (OD) and cell count. Wild-type C. necator H16 cells were cultured under autotrophic conditions. (A) Time course of growth curve based on OD (green) and cell count (blue). Error bars represent standard deviations of four independent biological samples. (B) Comparison of OD values and cell counts at each sampling point (black plots). The data were further divided into two groups: before 36 h (C) and after 36 h (D). Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rs), p-values, and linear regression equations with R2 values (dotted lines) are presented for each group.

Increase in cell volume associated with polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production and time course of nitrogen depletion and guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) accumulation. Time-course analysis of C. necator H16 cultures under autotrophic conditions. (A) The total cell volume was measured using a Coulter counter (Multisizer). (B) PHA production per 1 mL of culture was quantified using gas chromatography (GC). Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of four replicate experiments. (C–E) TEM images of cells sectioned at 24 h (C), 48 h (D), and 72 h (E). White bars indicate 1 μm. (F) Time-course of extracellular ammonium ions (NH4+) concentrations measured using the Ammonia Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). (G) Intracellular ppGpp levels measured by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOF MS). Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of four biological replicates.

Cell volume increase caused by PHA production

OD depends on multiple factors, including cell size and number15. The total cell volume per culture medium was evaluated using a Coulter counter, and its increase prior to 36 h mirrored the cell proliferation trend observed in the cell counts. However, even after cessation of proliferation, the total cell volume continued to increase (Fig. 2A). This suggests that factors other than the cell number contributed to the observed increase in total cell volume. C. necator H16 accumulates intracellular PHA in response to stress, including nutrient starvation11. Between 30 and 36 h, the nitrogen source (ammonium ions) was depleted, triggering the synthesis of guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), a signaling molecule involved in the stringent response (Fig. 2F and G)17. GC analysis confirmed that intercellular PHA accumulation started at the same time (Fig. 2B). The continued increase in the total cell volume seemed to be caused by PHA production. Morphological analysis using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) further supported this idea. At 24 h, the cells contained only a few small PHA granules, whereas at 48 h, multiple granules occupied most of the intracellular space (Fig. 2C, D). At 72 h, the number of granules further increased, with some cells containing more than 10 granules (Fig. 2E). The increase in PHA granules was accompanied by a clear increase in the cell size.

To confirm that PHA accumulation caused the observed increase in cell volume, we examined a mutant strain in which the PHA synthase gene (phaC) was disrupted. A gene-deletion strain of the restriction modification enzyme (∆A0006) served as the parent strain. The PHA non-producing mutant strain (∆A0006∆phaC) showed no detectable PHA production throughout the culture (Fig. 3A). Frequency distribution analysis of cell volumes over time revealed a rightward shift in the parental strain as the culture progressed (Fig. 3B), whereas the peak positions for ∆A0006∆phaC remained the same at approximately 0.3 µm3 (Fig. 3C). After 30 h, the average cell volumes of the two strains were similar. However, after 36 h, the average cell volume of the parental strain increased, whereas that of ∆A0006∆phaC gradually decreased (Fig. 3D). Morphological observations of sectioned cells at 72 h further confirmed that ∆A0006∆phaC cells lacked the PHA-derived granule structures observed in ∆A0006 and exhibited a wrinkled membrane structure (Fig. 3E, F). These results demonstrate that PHA production directly contributes to an increase in cell volume.

Cell-volume evaluation of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)-deficient mutant. The parent strain (∆A0006) and the PHA-deficient mutant (∆A0006∆phaC) were cultured under autotrophic conditions, and their PHA production and cell volumes were compared. (A) PHA titers were measured by gas chromatography (GC). (B,C) Frequency distributions of cell volumes for ∆A0006 (B) and ∆A0006∆phaC (C) at 24 h (blue), 36 h (light blue), 48 h (orange), and 72 h (green), as measured by the Multisizer. (D) Average cell volume change during culture. (E,F) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the sectioned cells of ∆A0006 (E) and ∆A0006∆phaC (F) at 72 h. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of three replicate experiments.

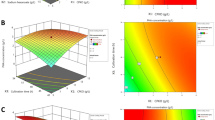

Evaluation of PHA production based on cell volume

A mutant strain with high PHA production was constructed to evaluate whether PHA production could be assessed using volume measurements. The strains ∆A0004-9 and ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG constructed at Kaneka Corporation were used. This mutant, ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG, had its native PhaC gene (H16_1437) replaced with a modified PHA synthase (PhaCAcNSDG) derived from Aeromonas caviae. Aeromonas caviae produces PHAs, such as P(3HB-co-3HHx), from plant oils and fatty acids18. The PHA synthase of A. caviae (PhaCAc) is an important enzyme in industrial PHA production that is capable of polymerizing 3HB and 3HHx monomers19. The modified enzyme PhaCAcNSDG has been shown to produce a higher 3HHx fraction than wild-type PhaCAc20,21. Furthermore, a C. necator H16 mutant expressing PhaCAcNSDG showed enhanced PHA production under heterotrophic conditions22. Using GC analysis, we confirmed that under autotrophic conditions, ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG exhibited higher PHA production than the parental strain. After 96 h of culture, the mutant strain produced 52.5 ± 1.85% PHA per dry cell weight (DCW), compared to 45.3 ± 0.82% PHA per DCW for the parental strain. The mutant strain exhibited a larger total cell volume per culture than that of the parental strain (∆A0004-9) after 72 h (Fig. 4A). The average cell volume of the ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG strain was significantly greater than that of the parental strain after 72 h (Fig. 4B). TEM observations of the sectioned cells revealed that, in the mutant strain, PHA granules, which were distinct from those in the parental strain, fused into larger intracellular granules that occupied most of the cell interior (Fig. 4C, D). This increase in intracellular PHA levels was likely responsible for the observed increase in cell volume. To evaluate whether PHA production could be quantitatively assessed based on volumetric data, the PHA titers at each sampling point between 30 h and 96 h were quantified using GC analysis. A plot of the PHA titer against the total cell volume per culture showed a positive correlation for the parental and high PHA-producing strains (Fig. 4E, F). A combined plot without strain distinction showed a similar positive correlation (Fig. 4G). To further examine this relationship, ANOVA was performed to compare the fit of two models: a strain-specific regression line model and a single regression line model. The single regression line model produced a residual sum of squares of 0.55 with 34 residual degrees of freedom. The strain-specific regression line model also had a residual sum of squares of 0.55, but with 32 residual degrees of freedom, resulting in a difference of 0.00012 in the residual sum of squares for the two additional degrees of freedom. The F-test reveals no significant differences between the two models (F = 0.0035, p = 0.996). These results suggest that the strain-specific regression line model does not outperform the single-regression line model. Consequently, PHA production (titer) across strains could be effectively compared and quantified using a single regression line based on cell volume. Additionally, the average cell volume strongly correlated with the amount of PHA per cell unit (Fig. 4H-J), suggesting that it is a valuable parameter for strain-to-strain comparisons of PHA productivity. It is important to note that the correlation between PHA titer and total cell volume is valid only during the PHA production phase, as the primary driver of volume increase during the proliferative phase is cell division rather than polymer accumulation. In contrast, the increase in average cell volume observed after 36 h coincides with the onset of PHA accumulation. Although titer-based metrics are widely used for process evaluation, material accumulation normalized per cell unit may serve as a useful parameter for assessing a cell’s intrinsic capacity to produce intracellular compounds independently of proliferation.

Cell-volume-based evaluation of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production in high-PHA producing mutants. The control strain (∆A0004-9) and a high-PHA-producing mutant (∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG) cultured under autotrophic conditions were compared based on cell volume. (A) Time course of the total cell volume per culture of ∆A0004-9 (blue) and ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG (orange). (B) Average cell volume transitions in the two mutants. Error bars are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicate experiments. (C,D) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of sectioned cells of ∆A0004-9 (C) and ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG (D) at 96 h. White bars represent 1 μm. (E–G) Comparison of the total cell volume increase and PHA production (titer). Correlation of total cell volume per culture with PHA titers quantified by gas chromatography (GC) for ∆A0004-9 (E) and ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG (F). (G) Combined plot without strain distinction with Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rs), p-values, and linear regression equations (dashed lines with R2 values). (H–J) Correlation between average cell volume and PHA accumulation per 1010 cells for ∆A0004-9 (H) and ∆A0004-9∆phaC::phaCAcNSDG (I). The average cell volume was calculated by dividing the total cell volume by the cell concentration at each time point. PHA accumulation per 1010 cells was determined by converting the PHA content measured by GC and normalizing it to the cell concentration. (J) A combined plot without strain distinction, illustrating the overall correlation. Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rs), p-values, linear regression equations, and R2 values (dashed lines) are shown.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that cell number and volume can serve as reliable and quick indicators for assessing cell proliferation and material production in C. necator H16. We found that PHA titer correlated with total cell volume per culture, allowing us to track PHA production during the culture process under autotrophic conditions. This time-course monitoring enabled clear detection of the transition from the proliferation phase to the PHA production phase. By applying this method to a PHA-producing mutant, we directly compared its productivity with that of the parental strain during culture. These results suggest that this approach is valuable for evaluating and screening mutant strains for enhanced PHA production. Moreover, this method may have broader applications to other bacteria that produce intracellular storage compounds, offering a novel perspective on microbial bioproduction. Although demonstrated under autotrophic conditions in this study, the approach is also expected to be effective under heterotrophic conditions. However, PHA production under heterotrophic conditions—particularly by Kaneka Corporation—has already reached a commercially optimized level. In contrast, autotrophic production remains less developed and requires further innovation. Therefore, we focused our evaluation on autotrophic cultures, where productivity is still limited and the need for real-time monitoring tools is greater.

Turbidity, measured as OD, has long been used to measure bacterial population density. OD is quick, easy to measure, and enables real-time monitoring. However, the reliability of the OD has been questioned in several studies15,23,24. The correlation between OD and cell concentration decreased significantly after the onset of PHA production in C. necator H16 cells (Fig. 1). Mira et al.. and Beal et al.. proposed calibrating OD values using actual cell counts15,23; however, this approach is difficult for bacteria such as C. necator H16, which accumulate large intracellular reservoirs. PHA accumulation increases light scattering in OD measurements, making it appear as though cell density increased, even when cell numbers remained constant. This decoupling of OD from cell number makes OD an unreliable proliferation indicator for such strains.

Our results clearly distinguished the proliferation and PHA accumulation phases during C. necator H16 culture, based on cell counts and PHA production. Ammonium quantification in the medium indicated nitrogen depletion between 30 and 36 h, triggering a starvation response and a metabolic shift (Fig. 2F). Rapid accumulation of ppGpp, a second messenger of the starvation response, at the 36-hour mark supports this observation (Fig. 2G). ppGpp regulates cell growth and metabolism25,26. Its accumulation likely caused C. necator H16 to alter metabolism, halt cell division, and initiate PHA synthesis as a storage mechanism. Previous studies have reported that SpoT1 and SpoT2, ppGpp synthesis proteins in C. necator H16, regulate PHA synthesis and degradation27,28. Similar nutrient-dependent switches likely occur in other studies but may go unnoticed when OD is used as a proliferation indicator. OD may continue to increase after proliferation ceases, leading to misinterpretation. Therefore, accurate evaluation of microorganisms that accumulate intracellular storage compounds requires direct cell counts.

Separating proliferation and production phases provides advantages for improving material yield. In most microbial systems, these phases compete for carbon sources and reducing power29. An effective strategy to address this growth decoupling is to separate proliferation from production13. This relieves the metabolic burden during proliferation and allows resources to be redirected toward product synthesis. For instance, PHA production in Escherichia coli improves when glucose starvation is induced by switching carbon sources, creating distinct proliferation and production phases30. Growth decoupling likely also contributes to the high PHA yields, exceeding 80% of its DCW, achieved by C. necator H16. A two-stage culture strategy is commonly used, with the first stage for proliferation and the second for PHA accumulation31. Our method, which enables monitoring of phase transitions, may help optimize medium composition and culture conditions for CO₂-derived PHA production.

We demonstrated that total cell volume can serve as a rapid indicator of intracellular substances. Using this method, we evaluated a high-PHA-producing mutant strain in which the native PhaC1 (H16_A1437) gene was replaced with PhaCAcNSDG from Aeromonas caviae. The total cell volume per culture was positively correlated with the PHA titer, enabling quantitative evaluation of production and inter-strain differences. Cell volume can be evaluated simply and quickly using the Coulter principle or forward scatter light (FSC) of flow cytometers. Few current methods for intracellular product quantification offer real-time capability or simplicity. Most involve complex and time-consuming mass spectrometry (MS) procedures, such as cell lyophilization, chemical or enzymatic extraction, GC-MS, FTIR, and NMR analysis32,33. In contrast, our volumetric method can be completed in minutes, enabling real-time PHA assessment using a Coulter counter or flow cytometer. This is useful for developing online control tools for fermentation processes. However, as this method does not directly quantify PHA titer, calibration with precise analytical techniques such as GC-MS is required.

An alternative is fluorescence-based quantification using flow cytometry or spectrofluorometry of fluorescent dye-stained cells34. Although simple and fast, this approach lacks specificity, can be cytotoxic, and may misidentify target compounds. Thus, choosing a suitable method depends on the bacterial strain and target compound. This study offers a new option for researchers seeking efficient, real-time evaluation methods in microbial production systems.

We propose cell count and volume as reliable, rapid indicators for assessing proliferation and production in real time. These parameters can be rapidly and safely obtained using a Coulter counter, enabling continuous culture monitoring. Such data are essential for optimizing resource use in high-yield PHA production and are especially useful for evaluating multiple mutant samples simultaneously. Our approach links morphological changes with intracellular storage accumulation, providing a practical evaluation framework. Advances in cell imaging technologies, such as digital image analysis (DIA), could surpass traditional methods by enabling high-throughput morphological studies35,36. This study highlights the potential of these techniques to drive innovation in microbial production research.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. C. necator H16 (DSMZ-428, ATCC 17669) was purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). C. necator H16 and its derivatives were grown in 80 mL of mineral salt medium (Na2HPO4-12H2O, 11 g/L; KH2PO4, 1.9 g/L; (NH4)2SO4, 0.3 g/L; HEPES, 4.77 g/L, 200 g/L MgSO4-7H2O, 5 mL; and trace element solution, 1 mL). The composition of the trace element solution was as follows (per liter of 0.1 N HCl): CoCl2-6H2O, 0.0436 g; FeCl3-6H2O, 3.24 g; CaCl2-2H2O, 2.06 g; NiCl2-6H2O, 0.0236 g; and CuSO4-5H2O, 0.0312 g. Cells were incubated at an initial concentration of 1.0 × 107 cells/mL in a 300 mL Erlenmeyer flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer set to 445 rpm. Under autotrophic conditions, a gas mixture of H2 (85.5%), CO2 (10%), and oxygen (4.5%) was mixed in a gas blender (Cofloc, Tokyo, Japan) at a flow rate of 40 mL/min. The incubation temperature was maintained at 30 °C using a water bath. E. coli S17-1/λpir strain, used as a plasmid donor cell, was grown in 5 mL of LB medium at 37 °C. When necessary, the medium was supplemented with antibiotics.

Construction of recombinant strains

The plasmids and primers used are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Plasmid construction was performed using an In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA, USA). Detailed methods for plasmid and strain construction are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Cell proliferation and cell volume assessment

OD600 was measured using a UV mini spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Cell counts and volume measurements were performed using a particle size analyzer (Multisizer 4e; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) with a 30 μm aperture tube. Cell cultures were diluted in 20 mL of ISOTON II (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and 100 µL of the suspension was used for particle analysis, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The range corresponding to the cells was defined as the region encompassing the major peak, representing the predominant population of single cells. Average cell volume was calculated by dividing the total cell volume by the cell concentration.

Quantification of PHA by GC

PHA accumulation was analyzed using a modified version of the method based on Jendrossek37. After incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2,300 × g at 25 °C. The cells were dried under reduced pressure, then suspended in 1 mL of chloroform. Next, 1 mL of 15% (v/v) H2SO4-methanol was added, and methanolysis was performed at 100 °C for 140 min. After cooling, 0.5 mL of Milli-Q water was added to the mixture, which was then stirred and centrifuged. The mixture separated into two layers; the lower chloroform layer containing 3HB methyl esters was analyzed by GC with flame ionization detection (GC-FID). GC analysis was performed using a GC-2014 system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with an Agilent DB-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm) and helium as the carrier gas. The detector temperature was set to 280 °C. The H2 flow rate was 40 mL/min, the air flow rate was 400 mL/min, and the makeup gas flow rate was 28 mL/min. The elution program was as follows: initial temperature 70 °C (2 min hold), ramped at 10 °C/min to 280 °C, and held for 7 min.

TEM of sectioned cells

Bacterial cells dried in ethanol were transferred to a resin (Quetol 812; Nisshin EM Co., Tokyo, Japan) and polymerized at 60 °C for 48 h. Ultra-thin Sect. (70 nm) using a diamond knife on an ultramicrotome (ULTRACUT UCT; Leica, Vienna, Austria). The sections were then mounted on copper grids, stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 15 min at room temperature, rinsed with distilled water, and stained with lead solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) for 3 min. Grids were observed under a TEM (JEM-1400plus; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV. Digital images (3,296 × 2,472 pixels) were obtained using a CCD camera (EM-14830RUBY2; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Quantification of nitrogen

Ammonium concentrations in the culture medium were measured using a commercial Ammonia Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of PpGpp

Intracellular ppGpp concentrations were measured by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight MS using an Agilent G7100 CE system coupled with an Agilent G6230AA liquid chromatography/mass selective detector time-of-flight system, as described previously38,39.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of more than three replicate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Python (v3.13.0), with one-way ANOVA applied. A 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) was used for all comparisons.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Aragno, M. & Schlegel, H. G. The hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria in The Prokaryotes (eds Starr, M. P., Stolp, H., Trüper, H. G., Balows, A. & Schlegel, H. G.) 865–893 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, (1981).

Pavan, M. et al. Advances in systems metabolic engineering of autotrophic carbon oxide-fixing biocatalysts towards a circular economy. Metab. Eng. 71, 117–141 (2022).

Woern, C. & Grossmann, L. Microbial gas fermentation technology for sustainable food protein production. Biotechnol. Adv. 69, 108240 (2023).

Brigham, C. Perspectives for the biotechnological production of biofuels from CO2 and H2 using Ralstonia eutropha and other Knallgas bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 2113–2120 (2019).

Arikawa, H., Matsumoto, K. & Fujiki, T. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production from sucrose by Cupriavidus necator strains harboring Csc genes from Escherichia coli W. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 7497–7507 (2017).

Raberg, M., Volodina, E., Lin, K. & Steinbüchel, A. Ralstonia eutropha H16 in progress: applications beside PHAs and establishment as production platform by advanced genetic tools. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 38, 494–510 (2018).

Laranjeiro, F. et al. Comparative assessment of the acute toxicity of commercial bio-based polymer leachates on marine plankton. Sci. Total Environ. 946, 174403 (2024).

Zytner, P. et al. A review on polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production through the use of lignocellulosic biomass. RSC Sustain. 1, 2120–2134 (2023).

Vicente, D., Proença, D. N. & Morais, P. V. The role of bacterial polyhydroalkanoate (PHA) in a sustainable future: A review on the biological diversity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20, 2959 (2023).

Taguchi, S. & Matsumoto, K. Evolution of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesizing systems toward a sustainable plastic industry. Polym. J. 53, 67–79 (2021).

Tang, R., Peng, X., Weng, C. & Han, Y. The overexpression of Phasin and regulator genes promoting the synthesis of polyhydroxybutyrate in Cupriavidus necator H16 under nonstress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e0145821 (2022).

Vlaeminck, E. et al. Pressure fermentation to boost CO2-based poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production using Cupriavidus necator. Bioresour Technol. 408, 131162 (2024).

Banerjee, D. & Mukhopadhyay, A. Perspectives in growth production trade-off in microbial bioproduction. RSC Sustain. 1, 224–233 (2023).

Han, Y. & Zhang, F. Control strategies to manage trade-offs during microbial production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 66, 158–164 (2020).

Mira, P., Yeh, P. & Hall, B. G. Estimating microbial population data from optical density. PLoS One. 17, e0276040 (2022).

Braunegg, G., Sonnleitner, B. & Lafferty, R. M. A rapid gas chromatographic method for the determination of poly-ß-hydroxybutyric acid in microbial biomass. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6, 29–37 (1978).

Irving, S. E., Choudhury, N. R. & Corrigan, R. M. The stringent response and physiological roles of (pp)pGpp in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 256–271 (2021).

Kobayashi, G., Shiotani, T., Shima, Y. & Doi, Y. Biosynthesis and characterization of Poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from oils and fats by Aeromonas sp. OL-338 and Aeromonas sp. FA-440. Stud. Polym. Sci. 410–416 (1994).

Fukui, T. & Doi, Y. Cloning and analysis of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) biosynthesis genes of Aeromonas caviae. J. Bacteriol. 179, 4821–4830 (1997).

Tsuge, T. et al. Combination of N149S and D171G mutations in Aeromonas caviae polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and impact on polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277, 217–222 (2007).

Kichise, T., Taguchi, S. & Doi, Y. Enhanced accumulation and changed monomer composition in polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) copolyester by in vitro evolution of Aeromonas caviae PHA synthase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 2411–2419 (2002).

Sato, S., Maruyama, H., Fujiki, T. & Matsumoto, K. Regulation of 3-hydroxyhexanoate composition in PHBH synthesized by Recombinant Cupriavidus necator H16 from plant oil by using butyrate as a co-substrate. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 120, 246–251 (2015).

Beal, J. et al. Robust Estimation of bacterial cell count from optical density. Commun. Biol. 3, 512 (2020).

Martinez, S. & Déziel, E. Changes in polyhydroxyalkanoate granule accumulation make optical density measurement an unreliable method for estimating bacterial growth in Burkholderia Thailandensis. Can. J. Microbiol. 66, 256–262 (2020).

Amato, S. M., Orman, M. A. & Brynildsen, M. P. Metabolic control of persister formation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell. 50, 475–487 (2013).

Potrykus, K., Murphy, H., Philippe, N. & Cashel, M. PpGpp is the major source of growth rate control in E. coli. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 563–575 (2011).

Juengert, J. R. et al. Absence of PpGpp leads to increased mobilization of intermediately accumulated poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 83 (2017).

Brigham, C. J., Speth, D. R., Rha, C. & Sinskey, A. J. Whole-genome microarray and gene deletion studies reveal regulation of the polyhydroxyalkanoate production cycle by the stringent response in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 8033–8044 (2012).

Zou, Y. et al. A self-regulated network for dynamically balancing multiple precursors in complex biosynthetic pathways. Metab. Eng. 82, 69–78 (2024).

Bothfeld, W., Kapov, G. & Tyo, K. E. J. A glucose-sensing toggle switch for autonomous, high productivity genetic control. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1296–1304 (2017).

Ronďošová, S., Legerská, B., Chmelová, D., Ondrejovič, M. & Miertuš, S. Optimization of growth conditions to enhance PHA production by Cupriavidus necator. Fermentation 8, 451 (2022).

Rodrigues, A. M. et al. Polyhydroxyalkanoates from a mixed microbial culture: extraction optimization and polymer characterization. Polym. (Basel). 14, 2155 (2022).

Prepare, C. W. Extraction, production and purification of added value products from urban wastes — Part 2: Extraction and purification of PHA biopolymers. https://www.cencenelec.eu/media/CEN-CENELEC/News/Workshops/2023/2023-05-11%20-%20PHA/prcwa_17897-2.pdf

Elain, A. et al. Rapid and qualitative fluorescence-based method for the assessment of PHA production in marine bacteria during batch culture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31, 1555–1563 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. A comprehensive review of image analysis methods for microorganism counting: from classical image processing to deep learning approaches. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 2875–2944 (2022).

Zhou, S., Chen, B., Fu, E. S. & Yan, H. Computer vision Meets microfluidics: a label-free method for high-throughput cell analysis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 116 (2023).

Juengert, J. R., Bresan, S. & Jendrossek, D. Determination of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) content in Ralstonia eutropha using gas chromatography and nile red staining. Bio-protocol 8, (2018).

Hidese, R. et al. PpGpp accumulation reduces the expression of the global nitrogen homeostasis-modulating NtcA Regulon by affecting 2-oxoglutarate levels. Commun. Biol. 6, 1285 (2023).

Hasunuma, T. et al. Dynamic metabolic profiling of cyanobacterial glycogen biosynthesis under conditions of nitrate depletion. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 2943–2954 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michiaki Owa (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) and Hisashi Arikawa (Kaneka Corporation, Hyogo, Japan) for their technical advice. We thank Ms. Suxiang Zhang and Ms. Mamiko Kajikawa for their technical assistance. This work was supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), Green Innovation Fund Project, Japan, and the Program for Forming Japan’s Peak Research Universities (J-PEAKS) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K. designed the study, conducted experiments, and drafted the manuscript. N.A., K.T. and K.N. interpreted the results and revised the manuscript. M. M. conducted the experiments. K.M., N. Y., and A.K. commented on the study and manuscript and assisted with laboratory management. T.H. designed the study, revised the manuscript, and supervised the study. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamasaka, K., Abekawa, N., Takeda, K. et al. Monitoring proliferation and material production of Cupriavidus necator H16 using cell count and volume measurement. Sci Rep 15, 30416 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16567-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16567-4