Abstract

According to the China National Mental Health Development Report (2021–2022), only 46.7% of Chinese university students report experiencing meaning in life (MIL), while approximately 40% exhibit existential confusion, highlighting a critical psychological challenge. This study examines, in Chinese college students, how connectedness (to self, others, and nature) relates to meaning in life and whether basic psychological needs mediate these associations, integrating variable- and person-centered approaches. A cross-sectional study was conducted with 807 college students (mean age = 19.40 ± 1.25 years, 75.22% female) from colleges in Guangdong Province, China. Participants completed validated scales assessing connectedness to self (mindfulness), others (social connectedness), and nature, along with basic psychological needs and MIL. Both variable-centered (parallel mediation analysis) and person-centered (latent profile analysis) approaches were employed to provide complementary perspectives on the research questions. Variable-centered analysis confirmed mediation by basic psychological needs across all connectedness dimensions, with competence satisfaction showing the strongest effect (β = 0.20, 95% CI [0.13, 0.27]). Person-centered analysis identified three distinct connectedness profiles: Alienated Type (7.56%, characterized by low connectedness across dimensions), Moderated Type (65.43%, moderate connectedness levels), and Enriched Type (27.01%, high connectedness across all dimensions). Profile-based mediation analysis confirmed competence satisfaction as the primary mediator, with the Enriched Type showing the strongest indirect effect relative to the Alienated Type (β = 0.60, 95% CI [0.38, 0.84]). Our findings demonstrate that competence satisfaction is the primary mechanism linking multifaceted connectedness to MIL in Chinese college students. The distinct profiles underscore the need for tailored interventions rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. This study extends self-determination theory by revealing how integrated connectedness patterns foster MIL, offering a novel framework for targeted well-being initiatives for Chinese college students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Meaning in life

The China National Mental Health Development Report (2021–2022) indicates only 46.7% of university students report meaning in life (MIL), with approximately 40% experiencing existential confusion1highlighting the urgent need for intervention in Chinese higher education. MIL, defined as an individual’s perception of coherence, purpose, and existential significance in their life2is a cornerstone of psychological well-being3. For college students, a population navigating critical developmental transitions in identity and career, MIL is particularly vital. Empirical evidence robustly demonstrates that higher levels of MIL in this demographic are associated with numerous positive outcomes, including greater academic engagement4,5enhanced resilience against stress6and lower levels of depression and anxiety7. Conversely, a lack of meaning, often termed an “existential vacuum“8is a significant risk factor, correlating strongly with increased suicidal ideation9,10and maladaptive behaviors such as internet addiction11,12. Thus, identifying the predictors that cultivate MIL is not merely an academic exercise but a critical priority for promoting mental health and fostering positive development among college students. Based on his Holocaust experiences, Viktor Frankl introduced logotherapy to psychology in the mid-1940s, positing that the will to meaning serves as a fundamental human motivation that can sustain individuals through extreme adversity8. Frankl’s “existential vacuum” correlates with psychological distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation)2,3,8,13confirming MIL’s critical role in mental health.

Contemporary research conceptualizes MIL as multidimensional. Steger et al. proposed an influential two-dimensional model comprising presence of meaning (cognitive awareness of purpose and values) and search for meaning (motivational engagement in purpose exploration)13validated cross-culturally including in China14. Martela and Steger15 refined this as three dimensions: coherence (life comprehensibility), purpose (goal-directedness), and significance (existential worth), offering a nuanced meaning construction framework. MIL demonstrates protective effects across development, enhancing mental stimulation16well-being17and adaptive health behaviors18.

While a robust body of literature confirms a positive association between various forms of connectedness and MIL, several critical research gaps persist. First, the precise psychological mechanisms underlying this relationship remain under-explored. Although self-determination theory (SDT) offers a promising framework, it is unclear how different types of connectedness (e.g., to self, others, nature) translate into MIL through the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Second, existing research has predominantly adopted a variable-centered approach, examining these connectedness dimensions in isolation. This approach, which examines each dimension in isolation, overlooks the potential synergistic effects that arise from the interplay of these dimensions and fails to capture the heterogeneity in how individuals combine these connections into holistic profiles. Third, there is a pressing need to investigate these dynamics within the specific socio-cultural context of Chinese college students, a population reported to be facing significant existential challenges. Consequently, it remains unknown whether universal mechanisms apply or if distinct patterns of connectedness exist within this group.

Connectedness and meaning in life

Connectedness is defined as a positive psychological resource that fosters healthy interpersonal functioning and enhances psychological resilience, thereby contributing significantly to mental health and well-being19,20. Townsend and McWhirter19 propose a tripartite framework encompassing self (intrapersonal), others (interpersonal), and broader purpose (transpersonal) dimensions—a model that has received empirical support. Given that intrinsic needs for connectedness span all dimensions, and deficits in any dimension correlate with mental health risks19,20researchers advocate for holistic profile approaches rather than examining isolated dimensions. Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that connectedness enhances MIL, reduces loneliness, buffers stress, and promotes well-being19,20,21although the underlying mechanisms remain largely unexplored.

Connectedness to self

Klussman et al.22 defined connectedness to self (also known as self-connection) as an experiential state comprising: self-awareness (internal state recognition), self-acceptance (non-judgmental self-attitude), and self-alignment (behavior-value consistency). Similarly, Watts et al. characterized it as a connection with one’s inner states, including bodily sensations, emotions, and self-awareness, fostering self-understanding and acceptance21the embodied and experiential nature of self-connection. Both definitions emphasize core components of mindfulness, such as self-awareness and acceptance23justifying the use of mindfulness measures as a proxy for connectedness to self. Grounded in this theoretical overlap and consistent with prior research19,21,22this study operationalizes connectedness to self using validated mindfulness measures as a robust proxy, based on the strong theoretical overlap between the constructs, particularly in their shared emphasis on awareness and acceptance. The emotion regulation model24 suggests that mindfulness-based interventions reduce automatic habitual responses and negative cognitive evaluations by cultivating present-moment awareness and nonreactive acceptance. Furthermore, a meta-analysis25 (N = 912) confirms mindfulness enhances MIL via decentering, authentic self-awareness, and positive experience focus.

Connectedness to others

Connectedness to others—subjective experiences of belonging and emotional closeness—constitutes a fundamental psychological need across cultures19providing significant support for mental health and MIL26. Baumeister and Leary’s belongingness hypothesis27 posits an evolutionary-based motivation for stable relationships, as fundamental as physiological needs. Social connectedness represents the satisfaction of belongingness needs, functioning as both a relationship outcome and psychological resource that enhances MIL through emotional support28meaningful engagement29identity reinforcement, and mental health promotion30. In line with SDT31the fulfillment of relatedness needs promotes social connectedness, which in turn enhances MIL in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Connectedness to nature

Watts et al.21 defined connectedness to the world as a multifaceted construct encompassing relationships with one’s environment, nature, and society, which is distinct from interpersonal connections. Connectedness to nature encompasses cognitive affiliation, emotional affinity, and behavioral commitment to nature32a construct that has been validated cross-culturally33 within the biophilic framework.

Stress reduction theory (SRT)34,35 posits that exposure to natural environments reduces psychological and physiological stress through dual pathways. The physiological pathway involves lowering cortisol levels, reducing blood pressure, and increasing parasympathetic activity, while the psychological pathway triggers positive emotions, attention restoration, and adaptive behaviors. Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated positive correlations between nature connectedness and MIL across Western36 and Chinese samples37.

Converging evidence confirms positive correlations between all connectedness dimensions (connectedness to self, others, nature) and MIL25,28,38. These robust findings support connectedness as fertile ground for meaning formation, emphasizing its importance as a potential MIL antecedent. However, existing research has predominantly examined these dimensions in isolation, leaving their integrated effects on MIL under-investigated—a gap the present study aims to address.

Basic psychological needs as a mediator

SDT31 posits that psychological flourishing requires satisfaction of three universal needs: competence (the need to feel effective and masterful in one’s actions), autonomy (the need to experience volition, self-governance, and authentic self-expression), and relatedness (the need to feel connected to, cared for, and significant in social relationships). Empirical evidence confirms bidirectional relationships between basic needs and connectedness39,40,41suggesting a pattern of reinforcement.

Connectedness and basic psychological need

Connectedness types provide environmental contexts facilitating need satisfaction through distinct cognitive, emotional, and behavioral mechanisms. We propose three pathways: (1) Connectedness to self enhances autonomy and competence through internal awareness and self-regulation. Self-connectedness also bolsters competence via accurate self-knowledge, as authenticity correlates with self-evaluation, given that authenticity requires and promotes accurate self-evaluation42. (2) Social connectedness primarily satisfies relatedness, while secondarily supporting autonomy and competence through distinct mechanisms. Supportive environments foster psychological safety for authentic expression43promoting autonomy by reducing evaluation fears. (3) Connectedness to nature uniquely satisfies all three needs, with pronounced autonomy and competence effects. Natural settings provide non-evaluative environments that foster intrinsic motivation44satisfying autonomy via perceived choice—distinct from social mechanisms45. Additionally, nature exploration provides graduated challenges with immediate feedback46enabling skill mastery that enhances competence. Ecological psychology demonstrates that nature connectedness satisfies relatedness through connection with living systems38,47.

Basic psychological needs and MIL

Basic need satisfaction underpins MIL maintenance, supporting cognitive and affective meaning dimensions. Autonomy satisfaction enables value-congruent action, fostering coherent life narratives essential to MIL. Autonomy facilitates life experience integration into coherent self-narratives—a core meaning construction process48. Competence satisfaction reinforces purpose through efficacy perceptions and goal-directed engagement. Longitudinal evidence confirms competence satisfaction predicts MIL enhancement via self-worth15,49while relatedness satisfaction supports meaning and significance through emotional validation and perceived value. SDT’s needs-based model31 posits that environmental factors influence well-being via basic need satisfaction. We thus hypothesize that tripartite connectedness shapes MIL through mediation by basic psychological needs.

The present study: integrating Variable- and Person-Centered approaches

While the literature suggests that connectedness is a vital resource for MIL, and SDT provides a plausible mechanism, several critical gaps remain. First, the precise psychological mechanisms linking different forms of connectedness (to self, others, and nature) to MIL are not yet fully understood. Second, research has predominantly adopted a variable-centered approach that overlooks the synergistic effects of how individuals combine these connections into holistic profiles. Third, these dynamics have been under-investigated within the unique sociocultural context of Chinese college students, a population facing significant existential challenges.

To address these gaps, the present study integrates two complementary analytical frameworks. From a variable-centered perspective, we first aim to establish the generalizable, population-level mechanisms. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

The satisfaction of basic psychological needs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) mediates the relationships between connectedness (to self, others, and nature) and MIL.

However, a variable-centered approach can mask significant underlying heterogeneity50as individuals likely experience connectedness in qualitatively different ways. A person-centered approach is therefore essential. Our study advances this line of inquiry by addressing two critical limitations in prior person-centered research. First, we adopt a broader, tripartite conceptualization of connectedness, moving beyond the often-narrow focus on self-connection51,52 (e.g., high vs. low mindfulness) and social connection53,54 (e.g., lonely vs. connected) while systematically overlooking connectedness to nature. This omission is significant, as nature connectedness is an established predictor of well-being55 and can serve a supportive function56. Second, and critically, the interplay among these dimensions remains largely unexplored. Prior research has not clarified whether these different forms of connectedness operate in a dominant fashion (where one dimension prevails), a synergistic manner (where they mutually reinforce each other), or a compensatory pattern (where strength in one dimension compensates for deficits in others). By examining these potential configurations, our study moves from merely cataloging individual connections to understanding their holistic and dynamic relationship.

Drawing on the notion that connectedness is a positive psychological resource19we theorize that the connectedness patterns of Chinese college students are not random but reflect distinct adaptive strategies for navigating a developmental stage marked by identity formation and intense academic pressure. Building on this, we propose that a synergistic development model—where different forms of connection mutually reinforce each other—best explains their interplay. This leads us to anticipate three primary profiles: an ‘’Alienated’’ profile, characterized by global disconnection potentially linked to factors like avoidant attachment styles57; a normative ‘’Moderated’’ profile representing a functional equilibrium; and a synergistically high-connection ‘’Enriched’’ profile, where strengths across domains reinforce one another, aligning with theories of connectedness as a holistic resource19. These theoretical considerations lead to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2

Chinese college students exhibit heterogeneous connectedness profiles.

Hypothesis 3

Three qualitatively distinct profiles will emerge: a low-connection ‘Alienated’ profile, a normative ‘Moderated’ profile, and a synergistically high-connection ‘Enriched’ profile.

Finally, to bridge these two perspectives, we examine the psychological mechanisms that differentiate these profiles’ outcomes. We aim to understand why certain profiles are associated with higher MIL by testing the mediating role of need satisfaction within this person-centered framework. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4

The satisfaction of basic psychological needs mediates the relationship between connectedness profile membership and MIL.

Hypothesis 5

The indirect effect of profile membership on MIL via need satisfaction will be incrementally stronger for the Enriched and Moderated profiles, respectively, compared to the Alienated profile.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study recruited Chinese college students through convenience sampling. A total of 887 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding responses with completion times under 160 s, patterned or careless responses, and submissions with more than three missing items, 807 valid responses were retained, with a response rate of 90.98%. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 22 years (M = 19.40, SD = 1.25). Among these respondents, 200 (24.78%) were male and 607 (75.22%) were female. 434 students (53.78%) were from rural areas, and 367 (45.48%) from urban areas, and data for 6 students (0.074%) are missing regarding their place of origin. The sample comprised 667 non-medical students (82.65%) and 140 medical students (17.35%). The grade distribution is as follows: 349 freshmen (43.25%), 216 sophomores (26.77%), and 242 juniors (29.99%).

Procedure

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Mental Health, Shaoguan University (Approval No.: 2024XL0601).From October to November 2023, students from a university in Guangdong Province were selected as survey participants using a combined approach of random and snowball sampling. Informed consent was obtained on the first page of the survey before participants proceeded. Participation was voluntary and unpaid. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Measures

Connectedness to self. Connectedness to self was measured using the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI), developed by Walach et al.58 and adapted into Chinese by Chen and Zhou59. The scale consists of 13 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Rarely”) to 7 (“Always”). A sample item is, “I am open to my current experience.” Higher scores reflect greater connectedness to self. FMI comprises two dimensions: self-awareness and self-acceptance. In this study, the Cronbach’s ω for self-awareness, self-acceptance, and the overall questionnaire were 0.78, 0.80, and 0.87, respectively.

We acknowledge that mindfulness and self-connectedness are distinct constructs, but we chose mindfulness as a behavioral proxy based on strong conceptual overlap and recent theoretical frameworks. The core of this justification lies in their shared mechanism: non-judgmental, present-moment awareness. Self-connectedness requires an individual to be aware of their internal states—their feelings, values, and needs—without immediate judgment. Similarly, mindfulness is defined as the capacity to pay attention to present-moment experiences, both internal and external, with an attitude of acceptance. Thus, the skills measured by the FMI, such as the ability to notice one’s thoughts and emotions as they arise, are fundamental prerequisites for achieving a stable and authentic connection to oneself. This operationalization allows us to capture the behavioral tendency toward the self-awareness that underpins self-connection.

Connectedness to Nature. Connectedness to nature was assessed using the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS), developed by Mayer et al.32. and adapted into Chinese by Li et al.33. The CNS contains 14 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”). A sample item is, “I often feel a deep affinity for plants and animals.” Higher scores indicate stronger connectedness to nature. In this study, the Cronbach’s ω coefficient was 0.86.

Social Connectedness. Social connectedness was evaluated using the Social Connectedness Scale (SCS), originally developed by Lee et al.60 and adapted for Chinese populations by Fan et al.61. The SCS includes 20 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly Agree”). A sample item is, “I adapt quite well to new environments.” The scale comprises two dimensions: social connectedness and social disconnection. In the Chinese version, the social disconnection items are typically reverse-coded and combined with the connectedness items to form a total score. However, in this study, the original (non-reversed) scores were used to directly assess levels of disconnection. This decision is based on the conceptual premise that disconnection is not merely the mathematical inverse or absence of connection, but a distinct and active psychological experience of alienation and isolation. Using the un-reversed items (e.g., “I feel disconnected from the world”) allows us to directly measure this feeling of being apart, rather than simply inferring it from a low score on connection. This approach provides a more nuanced assessment of an individual’s social well-being. Higher scores in the respective subscales indicate stronger connectedness or greater disconnection. The Cronbach’s ω coefficients for the social connectedness, social disconnection, and overall scale were 0.90, 0.91, and 0.93, respectively. Since the Chinese version of the SCS was initially validated for middle school students, we conducted additional structural validity testing for the college student population using a one-factor, two-construct model. The results demonstrated acceptable fit: χ²/df = 6.63, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.88, SRMR = 0.05.

Basic Psychological Needs Scale. The Basic Psychological Need Scale (BPNS), developed by Gagné62 and adapted into Chinese by Liu et al.63was used to assess the fulfillment of psychological needs. The scale includes 19 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (“Completely Inconsistent”) to 7 (“Completely Consistent”). A sample item is, “I really enjoy interacting with the people I engage with.” Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction of basic psychological needs. BPNS consists of three dimensions: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. In this study, the Cronbach’s ω values for competence, autonomy, relatedness, and the overall scale were 0.76, 0.75, 0.81, and 0.91, respectively.

Meaning in Life. MIL was measured using the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), developed by Steger et al.13 and adapted into Chinese by Wang et al.14. The MLQ comprises 10 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (“Completely Inconsistent”) to 7 (“Completely Consistent”). A sample item is, “I have a clear understanding of the meaning of my life.” Higher scores indicate a stronger sense of MIL. In this study, the Cronbach’s ω for the subscales—presence of meaning and search for meaning—and for the overall scale were 0.89, 0.88, and 0.87, respectively.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.3. First, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses were performed to summarize sample characteristics and assess the bivariate relationships among all study variables. Second, we conducted parallel mediation analyses with the PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS to test our variable-centered hypotheses. We used 5,000 bootstrap samples to estimate the indirect effects of the connectedness dimensions on MIL via the three basic psychological needs. A mediation effect was deemed significant if the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) excluded zero. To ensure model assumptions were met, we also conducted post-hoc collinearity diagnostics to investigate potential multicollinearity among the mediators. Finally, to address the potential influence of the sample’s gender imbalance, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the PROCESS macro (Model 59) to test whether gender moderated the key mediation pathways.

For the person-centered mediation analyses, the latent profiles were treated as a multicategorical independent variable. We dummy-coded the profiles and selected the ‘Alienated’ profile as the reference group for both theoretical and interpretive reasons. Theoretically, the ‘Alienated’ profile, characterized by the lowest scores across all connectedness dimensions, serves as a conceptual baseline of disconnection. This allows for a direct and intuitive interpretation of the results, where the coefficients for the ‘Moderated’ and ‘Enriched’ profiles represent their effects relative to this baseline of lowest connection. This approach directly tests our hypothesis that higher levels of integrated connectedness are associated with more positive outcomes.

Latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted using Mplus 8.3 to classify distinct profiles of connectedness. We estimated models with one to five latent profiles and evaluated the optimal solution based on a combination of statistical fit indices and theoretical interpretability. Key fit indices included the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), adjusted BIC (aBIC), where lower values suggest a better fit. We also assessed the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR) and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), where a significant p-value (p < 0.05) indicates that a k-class model is superior to a k-1 class model64. Classification accuracy was evaluated using Entropy, with values closer to 1 (ideally > 0.8) indicating higher precision65. Finally, we required each profile to contain at least 5% of the total sample to ensure substantive meaningfulness66.

A systematic approach was taken to address missing data. Missing values were primarily concentrated in demographic variables, affecting only six cases. Given that this small number of deletions would have a negligible impact on statistical power, we employed listwise deletion for cases with missing control variables in the mediation analyses to ensure the robustness of the models. For the main study variables, the rate of missing data was extremely low (total missing data points < 100), and the pattern was assessed to be missing completely at random (MCAR). Under these conditions, mean substitution was used for imputation to maximize the retention of sample size for statistical analyses.

Results

Common method bias

To assess common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted67. The analysis extracted 12 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor accounting for 27.94% of the total variance—well below the critical threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias was not a serious concern in the present study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

The mean item scores (total score divided by the number of items) for connectedness to self, connectedness to nature, social connectedness, basic psychological needs, and MIL are shown in Table 1, along with their correlation matrix. Except for social disconnection, all other variables are significantly positively correlated with each other (all p-values < 0.001). Social disconnection is significantly negatively correlated with all other variables (all p-values < 0.001). Descriptive statistics for all demographic variables are reported in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Basic psychological needs as mediators of connectedness profiles and MIL: A Variable-Centered analysis of college students

To ensure the comparability of effect sizes across pathways, all continuous variables were standardized (z-scored) prior to mediation analysis. This procedure yields standardized beta coefficients, allowing for direct comparison of the relative strength of each mediator. We controlled for demographic variables and systematically examined the mediating effects, first in a series of single-mediator models (testing each need separately) and subsequently in parallel-mediator models where all three needs competed to explain the variance in MIL. All analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro (v4.2, Model 4) with 5,000 bootstrap samples. Detailed results are presented in Table 2. The diagrams of the mediation models are presented in Figures S1a–S1d of the Supplementary Materials.

Analyses of the mediation models revealed distinct patterns of relationships between various forms of connectedness and MIL through basic psychological needs satisfaction. In the simple mediation models (Models 1–12), all hypothesized indirect pathways were significant (none of the 95% confidence intervals contain zero), with the notable exception of the social connectedness→relatedness→MIL pathway (indirect effect β = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.08]), indicating that basic psychological needs predominantly mediate the relationship between connectedness and MIL. Therefore, H1 was partially supported.

However, when all three needs were tested simultaneously in the more stringent parallel mediation models, a clearer hierarchy emerged: competence satisfaction was the primary and most robust mediator across all forms of connectedness. Specifically, competence satisfaction significantly mediated the effects of connectedness to self (indirect effect β = 0.12, 95% CI [0.07, 0.17]), connectedness to nature (indirect effect β = 0.10, 95% CI [0.06, 0.14]), social connectedness (indirect effect β = 0.20, 95% CI [0.13, 0.27]), and social disconnection (indirect effect = −0.21, 95% CI [−0.28, −0.14]) on MIL.

The mediating pathways demonstrated distinct patterns across different forms of connectedness. Connectedness to self operated primarily through competence satisfaction, while connectedness to nature functioned through both competence and autonomy satisfaction (indirect effect β = 0.06, 95% CI [0.03, 0.10]).

Social connectedness exhibited a complex pattern with a positive indirect effect through competence satisfaction and, unexpectedly, a negative indirect effect through relatedness satisfaction (indirect effect β = −0.11, 95% CI [−0.19, −0.02]). This counterintuitive finding may suggest a suppression effect or potential competing mechanisms that warrant further investigation.

Conversely, social disconnection demonstrated significant negative indirect effects through both competence and autonomy satisfaction (indirect effect β = −0.11, 95% CI [−0.19, −0.04]).

Latent profile analysis and naming of latent profiles

A latent profile model was established using raw scores from connectedness to self, connectedness to nature, social connectedness and social disconnection as indicators, and the results are shown in Table 3. Model fit indices demonstrated that AIC, BIC, and aBIC values decreased continuously with increasing numbers of latent class profiles, indicating progressive improvement in model fit. The 5-class solution achieved the highest classification accuracy (Entropy = 0.865); however, minimum class probability was 2.11% (< 5%). As shown in Table 3, while the AIC, BIC, and aBIC values continued to decrease up to the 5-class solution, we carefully evaluated solutions from 2 to 5 classes based on both statistical indices and theoretical interpretability. The 5-class solution was rejected because one class contained only 2.11% of the sample, falling below the recommended 5% threshold. The four-profile solution, while statistically sound, was also dismissed as it produced two conceptually redundant profiles by splitting the large moderate group from the three-profile solution into two nearly identical subgroups, offering minimal additional theoretical insight. The three-profile solution was ultimately selected as optimal. It demonstrated strong statistical fit (e.g., Entropy = 0.836, significant LMR and BLRT) and yielded three qualitatively distinct and theoretically meaningful profiles. This solution provided the most parsimonious yet interpretable structure, aligning with our hypotheses about distinct developmental patterns. (For a visual comparison of the three- and four-profile solutions, see Supplementary Figure S2a and S2b).

In line with Hypothesis 2, three distinct connectedness profiles were identified (Fig. 1):

The Alienated Profile (n = 61, 7.56%) was characterized by uniformly low scores on self, nature, and social connectedness and the highest score on social disconnection. The Enriched Profile (n = 218, 27.01%) exhibited the opposite pattern, with the highest scores on all positive connectedness dimensions and the lowest score on social disconnection. The Moderated Profile (n = 528, 65.43%), representing the majority of the sample, displayed moderate levels across all four indicators. These findings confirm the existence of heterogeneous connectedness patterns (Hypothesis 2) and provide initial support for the specific profile structures proposed in Hypothesis 3.

Impact of latent profile of connectedness on basic psychological needs and MIL among college students

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) examined differences in basic psychological needs and MIL across connectedness latent profile types, with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. However, due to violations of the homogeneity of variance assumptions for autonomy and relatedness (as indicated by Levene’s test), a Kruskal-Wallis (H) test was conducted to examine differences among connectedness types. All variables showed significant profile differences (p < 0.001), with consistent Alienated < Moderated < Enriched ordering. These significant profile differences confirm Hypothesis 3 (profile differences exist), with detailed results presented in Table 4.

Basic psychological needs as mediators of connectedness and MIL: a person-Centered analysis of college students

To comprehensively assess the mediating relationship of basic psychological needs between psychological connection profiles and MIL, we used demographic variables as control variables and standardized the continuous variables (basic psychological needs, MIL) before employing two analytical approaches.

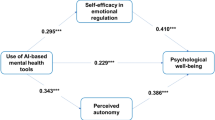

Building on the variable-centered approach described above, we adapted the analytical framework for our person-centered analysis by processing the dimensions of basic psychological needs in two ways. The first approach used simple mediation models with individual dimensions as mediators (Models 1–3 A), while the second approach employed parallel mediation models with all three dimensions simultaneously serving as mediators (Model 4 A). In both types of models, the independent variable (X) was the latent profile type of connectedness (with the alienated type as the reference), and the dependent variable was MIL. The results can be found in Table 5. Additionally, since the parallel mediation model controls for the influence of other mediating variables and thus has more practical significance. A path diagram of this model is presented in Fig. 2 for clarity (control variables are omitted for visual simplicity).

Analyses of relative indirect effects revealed distinct mediation patterns across connectedness profiles. In single-mediator models (Table 5, Models 1–3 A), both Moderated and Enriched profiles demonstrated significant positive indirect effects on MIL through all basic psychological needs when compared to the alienated profile. The enriched profile consistently exhibited stronger effects than the Moderated profile, with effect magnitudes approximately twice as large across pathways (competence: β = 0.65 vs. 0.29; autonomy: β = 0.57 vs. 0.29; relatedness: β = 0.26 vs. 0.11), establishing a clear dose-response relationship between profile intensity and need satisfaction. Hypothesis 4 is confirmed.

However, a more nuanced picture emerged in the parallel mediation model (Table 5, Model 4 A), where all three needs competed to explain variance in MIL. Competence satisfaction emerged as the sole significant and primary mediator. The indirect effect through competence remained robust for both Moderated (β = 0.27, 95% CI [0.16, 0.40]) and enriched profiles (β = 0.60, 95% CI [0.38, 0.84]). Notably, autonomy and relatedness became non-significant in this model, with relatedness showing direction reversal (Moderated: β = −0.08, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.02]; enriched: β =−0.18, 95% CI [−0.42, 0.06]), indicating a statistical suppression effect. Post-hoc collinearity diagnostics confirmed this was not due to problematic multicollinearity (Variance Inflation Factor values of 2.88 for competence, 2.94 for autonomy, and 2.25 for relatedness, VIFs < 3.0), but rather reflects the substantial shared variance among the needs. This finding suggests that while all needs are independently beneficial, competence is the dominant mechanism linking connectedness profiles to MIL when needs are considered simultaneously. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported, with competence as the key mediating pathway.

Sensitivity analysis for gender imbalance

To address the potential influence of the sample’s gender imbalance (75% female), we conducted a post-hoc moderated mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 59). We tested whether gender moderated the key pathways in our mediation models (Model 13–16、4 A). The moderated mediation analysis provided a nuanced picture. For most of the tested pathways, the moderating effect of gender was not statistically significant, suggesting that the proposed mechanisms generally operate similarly for both male and female participants. However, a significant interaction was found in the model examining self-connectedness (Model 13). Specifically, gender significantly moderated the path from self-connectedness to MIL (b = 0.225, SE = 0.102, t = 2.207, p = 0.028). A simple slopes analysis revealed that the positive relationship between self-connectedness and MIL was stronger for female participants than for male participants. This indicates that while self-connectedness is beneficial for all, its efficacy in promoting a sense of meaning may be particularly pronounced for females in our sample.

Discussion

This study employed a dual-method approach to investigate how multifaceted connectedness relates to MIL among Chinese college students, examining the mediating role of basic psychological needs. By integrating variable-centered and person-centered analyses, our findings offer two key contributions. First, we identify competence satisfaction as the primary universal mechanism linking diverse forms of connectedness to MIL. Second, we reveal three distinct connectedness profiles (Alienated, Moderated, Enriched), demonstrating significant heterogeneity in how students experience connectedness and underscoring the limitations of a one-size-fits-all perspective. These results not only bridge a gap in the literature, which has often examined connectedness dimensions in isolation, but also provide a more nuanced understanding of the synergistic pathways to well-being in a non-Western context.

Competence as the primary mediator: a variable-centered view

Our variable-centered analysis revealed that while all three basic psychological needs mediated the relationship between connectedness and MIL, competence satisfaction consistently emerged as the most potent mediator across all forms of connectedness (to self, nature, and others). This finding extends SDT43 by suggesting that, in the context of meaning-making, a hierarchy may exist among the basic psychological needs. While SDT posits all three needs as essential, our results indicate that the feeling of being effective and masterful in one’s environment may be the most critical psychological currency for converting experiences of connection into a robust sense of MIL. This aligns with theoretical frameworks that emphasize environmental mastery69 and efficacy70 as core components of a meaningful life.

Social connectedness showed the strongest mediation through competence, exceeding other dimensions substantially. This pattern specifies competence-validation as the core mechanism—social contexts provide performance feedback, skill demonstration platforms, and achievement recognition that jointly satisfy competence needs27,43.

Connectedness to self (mindfulness) mediated primarily via competence, with smaller effects through autonomy, suggesting that internal-state mastery—enhanced perceived control over thoughts and emotions—converts self-awareness into meaning24,25.

Connectedness to nature exhibited a more balanced mediation profile through both competence and autonomy satisfaction. This dual-pathway model aligns with both Attention Restoration Theory (ART)71 and Stress Reduction Theory (SRT)35 through distinct mechanisms: Cognitive restoration enhances problem-solving efficacy (related to competence), while demand-free environments facilitate self-determined action (related to autonomy)33,34.

In contrast, social disconnection exerted its harm primarily by undermining competence and autonomy. The particularly strong negative effect of disconnection via competence (β = −0.21) highlights that isolation is not merely a passive lack of belonging, but an active threat to one’s sense of efficacy, potentially reflecting the high value placed on social validation in a collectivistic context. This underscores the asymmetrical impact of social bonds: the pain of disconnection may be more potent than the pleasure of connection27,30.

Heterogeneity in connectedness: a person-centered perspective

Our person-centered analysis moves beyond population averages to reveal three distinct profiles of connectedness, a finding that challenges the assumption of homogeneity inherent in variable-centered methods50. More importantly, it provides empirical support for the idea that connectedness is not merely an aggregation of separate dimensions but manifests as holistic, synergistic patterns with unique psychological consequences. This confirms our hypothesis that individuals combine connections to self, others, and nature into qualitatively different configurations.

The Alienated Type, characterized by low connectedness across all dimensions and high social disconnection, represents a vulnerable population potentially at heightened risk for psychological problems including depression, anxiety, and existential distress3,30. From a theoretical perspective, this profile aligns with Frankl’s concept of the “existential vacuum”—a state characterized by a lack of meaningful connections and purpose8. The magnitude of their deficits in need satisfaction and MIL suggests they are not just disconnected, but potentially trapped in a cycle of isolation and low efficacy. This group represents a clear target for intensive, multi-faceted interventions that simultaneously rebuild connections to self, others, and nature.

The Moderated Type, appears to reflect a state of functional but not flourishing well-being. As the largest group, they represent the normative experience for many students: maintaining adequate connections to get by. Their moderate scores across all indicators suggest a “satisficing” strategy—a functional equilibrium that prevents distress but falls short of optimal psychological thriving17. This highlights a crucial opportunity for universal prevention and well-being promotion programs designed to move the majority from merely functioning to truly flourishing.

The Enriched Type embodies synergistic integration and psychological thriving. These students have successfully woven together strong connections to self, others, and nature, creating a powerful resource for well-being. Their high scores across all positive indicators and minimal disconnection align with models of optimal human functioning2 and serve as an aspirational benchmark. This pattern empirically supports the idea that meaning is a holistic outcome, consistent with Emmons’ view that it arises from integration across multiple life domains2,17. These students are not just connected; they are thriving because of the synergy between their connections.

Profile-Based mediation effects

The profile-based mediation analysis provides a compelling finding: competence satisfaction was the sole significant pathway linking connectedness profiles to MIL. This result refines our variable-centered findings, suggesting that when the holistic pattern of an individual’s connectedness is considered, the influence of autonomy and relatedness on MIL is statistically absorbed by the overwhelming role of competence. This reinforces the argument that feeling effective and capable is the central engine driving the translation of environmental resources (connectedness) into existential well-being (MIL).

Furthermore, the analysis revealed a striking dose-response relationship. The indirect effect through competence for the Enriched profile (β = 0.60) was more than double that of the Moderated profile (β = 0.27). This non-linear pattern suggests that the benefits of connectedness are not merely additive; they are multiplicative. Moving from a state of moderate to high, synergistic connectedness yields a disproportionately larger boost in meaning. This implies that interventions fostering holistic integration, rather than just incremental improvements in one area, may unlock the greatest potential for psychological thriving.

The non-significance of autonomy and relatedness as mediators in the parallel model does not necessarily diminish their importance for overall well-being. Rather, it suggests that within the specific process of meaning construction, competence may act as a more proximal and powerful mechanism. This aligns with recent work highlighting that daily experiences of competence are among the most robust predictors of MIL72. It is plausible that while autonomy and relatedness create a fertile ground for well-being, it is the tangible experience of competence—of successfully navigating one’s world—that crystallizes these supportive conditions into a coherent sense of purpose and significance.

A particularly noteworthy finding was the statistical suppression effect observed for relatedness in the parallel mediation model. While relatedness was a significant positive mediator when analyzed alone (Model 3 A), its indirect effect became non-significant and showed a negative trend (Moderated: β = −0.08, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.02]; enriched: β =−0.18, 95% CI [−0.42, 0.06]) when controlling for competence and autonomy. This does not imply that relatedness is unimportant for MIL; rather, it suggests a more complex interplay. While not statistically significant, this observed negative tendency for relatedness, particularly when competence needs are already strongly satisfied as the primary mediator, might tentatively suggest that an excessive or disproportionate focus on social connections could, in certain configurations, subtly diminish meaning by potentially detracting from personal effectiveness and achievement. More broadly, it suggests that the beneficial impact of social connections on MIL in this student population is largely channeled through its capacity to bolster feelings of competence and autonomy. The VIF scores confirmed moderate, but not problematic, intercorrelation among the needs (VIFs < 3.0), supporting this interpretation.

Theoretically, this finding provides a nuanced perspective on the functioning of basic needs for Chinese university students. It is plausible that in a highly competitive academic environment, social connections (relatedness) are valued most when they translate into tangible gains in capability and self-efficacy (competence). A sense of relatedness that exists in isolation from, or does not contribute to, a student’s sense of competence might be perceived as a distraction from academic and personal goals, thus failing to contribute positively to their overall sense of life’s meaning and purpose once the powerful influence of competence is accounted for. This highlights competence satisfaction not just as one of three needs, but as the potentially primary psychological nutrient that multifaceted connectedness must provide to foster MIL in this specific context.

Theoretical synthesis

First, our results resonate with the four-needs model of meaning proposed by Crescioni and Baumeister, which encompasses purpose, value, efficacy, and self-worth73. Particularly notable is our identification of competence satisfaction as the primary mediating mechanism, which directly corresponds to the “efficacy” dimension in their model. The gradient pattern of mediation effects across connectedness profiles suggests that as individuals progress from Alienated to Enriched configurations, their capacity to fulfill Baumeister’s efficacy need systematically increases. This enhanced efficacy capacity, in turn, generates stronger experiences of meaning.

Second, these findings can be integrated into Martela and Steger’s tripartite model of meaning (coherence, purpose, significance)15. Our results indicate that competence satisfaction may serve as a critical mechanism through which connectedness influences the “coherence” dimension. Specifically, competence experiences promote a sense of prediction and control over one’s environment, which is fundamental to Martela and Steger’s conceptualization of coherence as comprehensibility and predictability15. Simultaneously, the differentiated mediation effects produced by various connectedness profiles through competence reveal pathways by which connectedness impacts the “significance” dimension, particularly through providing a sense of value and contribution.

Third, our results enrich Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory48 by suggesting that basic psychological needs may not contribute equally to meaning construction. Instead, our findings indicate a hierarchical structure in which competence needs potentially occupy a privileged position, particularly within the context of integrated multidimensional connectedness profiles. This finding supports context-specific extensions of SDT, demonstrating that the relative importance of needs may vary according to environmental conditions and individual differences.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Future longitudinal studies tracking individuals across life transitions (e.g., university to workforce) and experimental interventions enhancing nature- and self-connection are needed to establish causality.

Second, findings are limited to Chinese college students, constraining generalizability. Cross-cultural research across diverse populations (adolescents, working adults, retirees) and cultural contexts (individualistic societies) is essential to determine whether competence universally drives meaning or varies culturally.

Third, the high Heterotrait-Monotrait ratios between social connectedness and basic psychological needs (0.740-0.896) indicate substantial conceptual overlap, complicating the disentanglement of unique contributions. Future research should employ measurement strategies that better distinguish social integration from psychological need satisfaction.

Implications for practice

The person-centered findings underscore the inadequacy of a uniform approach to student well-being and offer a data-driven framework for targeted intervention. Universities can leverage these profiles for proactive screening, tailored intervention matching, and systemic curriculum design.

Specifically, brief screening instruments based on self-, other-, and nature-connectedness could be deployed during student intake to identify individuals aligning with the at-risk ‘Alienated’ profile, enabling preemptive support. This profiling facilitates a transition from generic recommendations to precise intervention matching. For example, students in the ‘Alienated’ profile necessitate foundational, low-barrier support, such as initial one-on-one counseling followed by structured, skill-building workshops, rather than potentially overwhelming large-group activities. Conversely, the majority ‘Moderated’ profile is well-suited for universal psychoeducational programs that offer a diverse portfolio of activities (e.g., mindfulness practice, volunteerism, nature engagement) to encourage their transition toward an enriched state. Finally, individuals in the ‘Enriched’ profile should not be viewed as intervention targets but as a valuable resource to be recruited and trained as peer mentors or wellness ambassadors, thereby leveraging their strengths to support the wider student community.

Beyond individual interventions, these findings can inform proactive curriculum and environmental design. First-year experience seminars, for instance, can be structured to systematically cultivate different forms of connection and need satisfaction through integrated assignments like reflective journaling (self-connection), mandatory collaborative projects (other-connection and competence), and campus-based ecological activities (nature-connection). Such an approach would help construct a supportive university ecosystem wherein all students, irrespective of their initial profile, are afforded opportunities to flourish.

Conclusion

This study advances understanding of meaningful living through integrated variable-centered and person-centered analyses, yielding two key insights. First, competence serves as the primary psychological mechanism translating diverse connections into meaning. Second, individuals experience connectedness holistically through Alienated, Moderated, or Enriched profiles, with optimal meaning emerging from synergistic integration across self, others, and nature.

Theoretically, our findings link environmental resources (connectedness), psychological needs (competence), and existential well-being (meaning). Practically, they suggest interventions should transcend promoting social ties alone, instead fostering environments where individuals develop competence through their connections.

Data availability

The data are available upon justified request. Kindly contact the corresponding author (Danling Zhan, e-mail: psytopic11@163.com). The authors are grateful to Professor Yang Ying of Tianjin University for his valuable suggestions on the structure of this manuscript.

References

Fu, X. L., Zhan, K., Chen, X. F. & Chen, Z. Y. Blue Book of Mental Health: Report on the Development of Chinese National Mental Health (2021–2022) (Social Sciences Academic, 2023).

Emmons, R. A. Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. in Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived 105–128American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US, (2003).

Glaw, X., Kable, A., Hazelton, M. & Inder, K. Meaning in life and meaning of life in mental health care: an integrative literature review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 1–13 (2016).

Cai, Y. et al. A Cross-lagged longitudinal study of bidirectional associations between meaning in life and academic engagement: the mediation of hope. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 19, 2665–2684 (2024).

Wei, J., Yi, C., Ti, Y. & Yu, S. The implications of meaning in life on college adjustment among Chinese university freshmen: the indirect effects via academic motivation. J. Happiness Stud. 25, 65 (2024).

Zhou, S., Jiang, L., Li, W. & Leng, M. Meaning in life from a cultural perspective: the role of cultural identity, perceived social support, and resilience among Chinese college students. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 91 (2025).

Chen, Q. et al. The relationship between search for meaning in life and symptoms of depression and anxiety: key roles of the presence of meaning in life and life events among Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 282, 545–553 (2021).

Wong, P. T. P. Viktor frankl’s meaning-seeking model and positive psychology. in Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology 149–184Springer, New York, NY, (2014).

Li, S., Luo, H., Huang, F. & Wang, Y. Siu Fai yip, P. Associations between meaning in life and suicidal ideation in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 158, 107477 (2024).

Mingming, C., Lian, X. & Huiping, Z. Stress and suicidal ideation among Chinese college students: the role of meaning in life. Death Stud. 48, 1121–1128 (2024).

Wang, L., Fu, J., Wang, T. & Chen, I. J. Internet addiction and suicidal ideation in Chinese college students: the role of meaning in life and social support. J. Psychol. Afr. 34, 107–113 (2024).

Kaya, A., Türk, N., Batmaz, H. & Griffiths, M. D. Online gaming addiction and basic psychological needs among adolescents: the mediating roles of meaning in life and responsibility. Int. J. Ment Health Addict. 22, 2413–2437 (2024).

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S. & Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 53, 80–93 (2006).

Wang, M. C. & Dai, X. Y. Chinese meaning in life questionnaire revised in college students and its reliability and validity test. Chin J. Clin. Psychol 459–461 (2008).

Martela, F. & Steger, M. F. The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 11, 531–545 (2016).

Waytz, A., Hershfield, H. E. & Tamir, D. I. Mental simulation and meaning in life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 336–355 (2015).

Li, J. B., Dou, K. & Liang, Y. The relationship between presence of meaning, search for meaning, and subjective well-being: A three-level meta-analysis based on the meaning in life questionnaire. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 467–489 (2021).

Hu, Y. & Lü, W. Meaning in life and health behavior habits during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating role of health values and moderating role of conscientiousness. Curr. Psychol. 43, 14935–14943 (2024).

Townsend, K. C., McWhirter, B. T. & Connectedness A review of the literature with implications for counseling, assessment, and research. J. Couns. Dev. 83, 191–201 (2005).

Bellingham, R., Cohen, B., Jones, T., Spaniol, L. & Connectedness Some skills for spiritual health. Am. J. Health Promot. 4, 18–31 (1989).

Watts, R. et al. The watts connectedness scale: A new scale for measuring a sense of connectedness to self, others, and world. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 239, 3461–3483 (2022).

Klussman, K., Curtin, N., Langer, J. & Nichols, A. L. The importance of awareness, acceptance, and alignment with the self: A framework for Understanding Self-Connection. Eur. J. Psychol. 18, 120–131 (2022).

Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 10, 144–156 (2003).

Chambers, R., Gullone, E. & Allen, N. B. Mindful emotion regulation: an integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 560–572 (2009).

T.-W. Chu, S. & W. S. Mak, W. How mindfulness enhances meaning in life: A Meta-Analysis of correlational studies and randomized controlled trials. MINDFULNESS 11, 177–193 (2020).

Bailey, M., Cao, R., Kuchler, T., Stroebel, J. & Wong, A. Social connectedness: measurement, determinants, and effects. J. Econ. Perspect. 32, 259–280 (2018).

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. Routledge,. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. in Interpersonal Development 33 (2007).

Stavrova, O. & Luhmann, M. Social connectedness as a source and consequence of meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 11, 470–479 (2016).

Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A. & Jetten, J. Social connectedness and health. in Encyclopedia of Geropsychology 2174–2182Springer, Singapore, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-082-7_46

Wickramaratne, P. J. et al. Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: A scoping review. PLOS ONE. 17, e0275004 (2022).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: human needs and the Self-Determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

Mayer, F. S. & Frantz, C. M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 24, 503–515 (2004).

Li, N. & Wu, J. P. Revise of the connectedness to nature scale and its reliability and validity. China J. Health Psychol. 24, 1347–1350 (2016).

Yao, W., Zhang, X. & Gong, Q. The effect of exposure to the natural environment on stress reduction: A meta-analysis. Urban Urban Green. 57, 126932 (2021).

Ulrich, R. S. et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 11, 201–230 (1991).

Creedon, M. A. Connectedness To Nature and its Relationship To Meaning in Life (Massachusetts School, 2013).

Wang, C. Y., Luo, R. F. & Ji, S. H. Effect of nature connectedness on envy on social network sites usage: the mediating effects of meaning in life and upward social comparison. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 30, 619–624 (2022).

Howell, A. J., Passmore, H. A. & Buro, K. Meaning in nature: meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 1681–1696 (2013).

Hurly, J. & Walker, G. J. Nature in our lives: examining the human need for nature relatedness as a basic psychological need. J. Leis Res. 50, 290–310 (2019).

Xia, Y. et al. Longitudinal effects of school connectedness on adolescents’ academic engagement: mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction and the examination of gender differences in the mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 172, 108245 (2025).

Chang, J. H., Huang, C. L. & Lin, Y. C. Mindfulness, basic psychological needs fulfillment, and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 16, 1149–1162 (2015).

Kernis, M. H. & Goldman, B. M. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology vol. 38 283–357Academic Press, (2006).

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E. & Deci, E. L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 367–384 (2000).

Xie, M., Mao, Y. & Yang, R. Flow experience and City identity in the restorative environment: A conceptual model and nature-based intervention. Front Public. Health 10, (2022).

Weinstein, N., Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, coping, and emotional well-being. J. Res. Personal. 43, 374–385 (2009).

Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M. & Murphy, S. A. Happiness is in our nature: exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 12, 303–322 (2011).

Lumber, R., Richardson, M. & Sheffield, D. Beyond knowing nature: contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLOS ONE. 12, e0177186 (2017).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness (Guilford, 2017).

Hicks, J. A. & King, L. A. Meaning in life as a subjective judgment and a lived experience. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass. 3, 638–653 (2009).

Bergman, L. R. & Magnusson, D. A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 9, 291–319 (1997).

Bravo, A. J., Boothe, L. G. & Pearson, M. R. Getting personal with mindfulness: a latent profile analysis of mindfulness and psychological outcomes. Mindfulness 7, 420–432 (2016).

Pearson, M. R., Lawless, A. K., Brown, D. B. & Bravo, A. J. Mindfulness and emotional outcomes: identifying subgroups of college students using latent profile analysis. Personal Individ Differ. 76, 33–38 (2015).

Schmidt, R. D., Feaster, D. J., Horigian, V. E. & Lee, R. M. Latent class analysis of loneliness and connectedness in US young adults during COVID-19. J. Clin. Psychol. 78, 1824–1838 (2022).

Patte, K. A., Gohari, M. R. & Leatherdale, S. T. Does school connectedness differ by student ethnicity? A latent class analysis among Canadian youth. Multicult Educ. Rev. 13, 64–84 (2021).

Capaldi, C. A., Dopko, R. L. & Zelenski, J. M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol 5, (2014).

Wang, C. Y. & Lei, L. The influence of nature connectedness on college students’ depression: the mediation of loneliness and Self-esteem. Heilongjiang Res. High. Educ 89–93 (2018).

Jalilian, K., Momeni, K. & Jebraeili, H. The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between attachment styles and loneliness. BMC Psychol. 11, 136 (2023).

Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmüller, V., Kleinknecht, N. & Schmidt, S. Measuring mindfulness—the Freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Personal Individ Differ. 40, 1543–1555 (2006).

Chen, S. Y. & Zhou, R. L. Validation of a Chinese version of the Freiburg mindfulness Inventory-Short version. MINDFULNESS 5, 529–535 (2014).

Lee, R. M. & Robbins, S. B. Measuring belongingness: the social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J. Couns. Psychol. 42, 232–241 (1995).

Fan, X. L., Wei, J. & Zhang, J. F. On reliability and validity of social connectedness Scale-Revised in Chinese middle school students. J. Southwest. China Norm Univ. Sci. Ed. 40, 118–122 (2015).

Gagné, M. The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motiv Emot. 27, 199–223 (2003).

Liu, J. S. et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the basic psychological needs scale. Chin. Ment Health J. 27, 791–795 (2013).

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T. & Muthen, B. O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation studyvol 14, pg 535, Struct. Equ. Model.- Multidiscip. J. 15, 182–182 (2008). (2007).

Lubke, G. & Muthén, B. O. Performance of factor mixture models as a function of model size, covariate effects, and Class-Specific parameters. Struct Equ Model 14, (2007).

Wang, M. C. & Bi, X. Y. Latent Variable Modeling and Application with Mplus (Chongqing University, 2018).

Zhou, H. & Long, L. R. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol. Sci 942–950 (2004).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135 (2015).

Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H. Know thyself and become what you are: A Eudaimonic approach to psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 9, 13–39 (2008).

Yuen, M. & Datu, J. A. D. Meaning in life, connectedness, academic self-efficacy, and personal self-efficacy: A winning combination. Sch. Psychol. Int. 42, 79–99 (2021).

Joye, Y. & Dewitte, S. Nature’s broken path to restoration. A critical look at attention restoration theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 59, 1–8 (2018).

Machell, K. A., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L. & Nezlek, J. B. Relationships between meaning in life, social and achievement events, and positive and negative affect in daily life. J. Pers. 83, 287–298 (2015).

Crescioni, A. W. & Baumeister, R. F. The four needs for meaning, the value gap, and how (and whether) society can fill the void. In The Experience of Meaning in Life: Classical Perspectives, Emerging Themes, and Controversies (eds Hicks, J. A. & Routledge, C.) 3–15 (Springer Netherlands, 2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professor Yang Ying of Tianjin University for his valuable suggestions on the structure of this manuscript.

Funding

Shaoguan University 2025 Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project, SY2025SK01; Guangdong Provincial Department of Education 2024 Higher Education Ideological and Political Education Research Project, 2024GXSZ074.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yaoyao Cai designed the study, prepared the material, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, drafted and edited the manuscript, coordinated the study activities; Danling Zhan designed the study, coordinated the study activities, critically revised the draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors disclosed no relevant relationships.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Zhan, D. Basic psychological needs mediate connectedness and meaning in life among Chinese college students. Sci Rep 15, 30917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16688-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16688-w