Abstract

Patients with special healthcare needs (SHCN) face significant challenges in accessing dental rehabilitation services, particularly under general anesthesia (GA). This study examined the waiting time from screening to pre-anesthesia appointments and association between demographics and clinical factors with the waiting time among the SHCN patients treated at xxx Dental University Hospital. This retrospective study included 210 SHCN patients who had full mouth rehabilitation under GA. Analysis of the collected data showed that the average waiting time from clinical first visit screening appointment to pre-anesthesia clinic assessment was 10.06 ± 12.49 months while average complete dental rehabilitation surgery duration was 213.80 ± 101.98 min. ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) patients had the highest waiting time, while ASD (autism spectrum disorder) patients had the least waiting time, which was 14.29 and 9.29 months respectively. Findings indicate that systemic barriers, such as limited operating room (OR) availability and a lack of specialized professionals, contribute to prolonged waiting times and variability in treatment experiences. The study highlights the need for targeted reforms and tailored care approaches to improve access and outcomes for SHCN patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to dental care services should be easy for all individuals; however, a significant proportion of the world’s population still faces challenges accessing these essential services. This challenge is particularly pronounced for dental patients requiring special healthcare needs, as they often encounter greater difficulties obtaining the necessary dental care1,2. Studies have consistently shown that patients with special needs exhibit a higher prevalence of caries and periodontal problems. Furthermore, the literature highlights that the limited number of dental clinics equipped to accommodate these patients and long waiting times from appointment scheduling to doctor visits exacerbate these challenges3,4,5,6,7.

Statistics show that globally, over 500 million people experience one or more disabilities related to physical, mental, or sensory impairment and, therefore, need special care8. Statistics from Saudi Arabia indicate that about one million people live with one or more disabilities, highlighting the need for special care services for this population group8. Special consideration is required when providing dental treatment to special needs patients, and their circumstances often pose challenges to providing them with dental care9. Therefore, many individuals with special healthcare needs do not have the required healthcare access10. As global awareness of the need for dental healthcare services increases, universal access to dental care services has been recognized.⁸ should exist. However, researchers have identified some barriers that cause delays in receiving dental care for special needs patients2,11,12.

A study published in Saudi Arabia reported that 46.2% of dental patients with special healthcare needs faced difficulty accessing dental care services2. The psychological, behavioral, and physical complications associated with special needs patients are among the leading causes preventing them from receiving the required dental care11. On the other hand, dental professionals also require special skills and training to treat special needs patients. A lack of training programs and competence makes doctors uncomfortable treating these medically compromised patients due to their resistant behavior12,13. Due to these factors, access to dental care becomes limited, and the waiting time to receive treatment increases.

Therefore, the present study was designed to evaluate the waiting time from screening to dental rehabilitation required for special needs patients who visited King Saud Dental Hospital. The study objectives also included the association between demographics and clinical factors with the waiting time. Additionally, another study objective was to examine the association between the duration of surgery for complete dental rehabilitation and the categories of special needs.

Method

This retrospective study was conducted at King Saud Dental Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and involved special needs patients who visited the dental clinics between February 2018 and December 2024. All included patients required full mouth rehabilitation under general anesthesia and were therefore treated in the operating room (OR) of the dental hospital. As this was a retrospective study involving no direct contact with participants, the requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board. This waiver, along with the ethical approval to conduct the study, was granted by the Health Sciences Colleges Research on Human Subjects at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Institutional Review Board [IRB] Ref. No. 25/0218/IRB). The study was approved and carried out in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and regulations.

The study included all the special needs patients who got treated during the period specified for the study. Hence, sample size calculation was not required and there were 210 special needs patients who received treatment and therefore included in the study.

At King Saud University Dental Hospital, the appointment and treatment pathway for special care patients requiring dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia (GA) is managed through a dedicated and multidisciplinary protocol. These patients are initially assessed in the Special Care Dentistry (SCD) clinics, where comprehensive evaluations are conducted to determine the need for GA based on behavioral, medical, or cognitive challenges. Once found eligible, patients are referred to the anesthesia team for preoperative assessment. Appointments are then coordinated through a centralized scheduling system that considers operating room availability, anesthesiologist schedules, and case urgency. Medical clearance is obtained from the patient’s physician when necessary, and informed consent is documented. The process ensures thorough preoperative preparation, safe intraoperative management, and structured postoperative follow-up. This integrated approach enables vulnerable patient populations to receive complete dental rehabilitation in a controlled, hospital-based environment. No specific barriers to accessing dental care were identified in this study population during the scheduling or treatment process.

The data retrieved from the medical records consisted of demographic variables and surgery related variables. The demographic variables included (1) age and (2) gender. In addition, the independent variables were (1) type of special needs, (2) Medication used, (3) Follow up months, (4) Waiting time before surgery (months) and (5) Surgery duration (minutes). An excel file was generated containing one column for each variable and data for all 210 patients were retrieved.

For the analysis of the retrieved data, a statistical package for social sciences (SPSS v.23) was used. Mean, standard deviation, frequency distribution and bar diagrams were prepared for the descriptive analysis of the data. Normality of the data was checked by using Shapiro-Wilk test and insignificant results from the test provided that the data was normally distributed. Hence, parametric tests were used for inferential analysis. The two-independent samples T-test was used to study the difference between average surgery duration or waiting time with a type of special needs. The Pearson correlation test was used to find the correlation between age and surgery duration. All prices of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants in this study were presented in Table 1. The sample consists of 210 special needs patients, with males in the majority at 113 (53.8%). The average age of a patient was 20.81 ± 7.63 years old. Almost all patients had surgery under general anesthesia (GA) (99%, n = 208), except for 2 patients who underwent surgery with sedation only. The average surgery duration was reported as 213.80 ± 101.98 min, and the majority were on medications for their related systemic conditions (58.1%, n = 122). Among the types of special needs, ASD (autism spectrum disorder) was reported in 52 (23%) patients, followed by ID (Intellectual Delay) in 42 (18%), Epilepsy in 37 (16%), and ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) in 14 (6%).

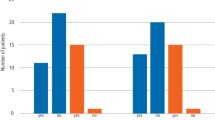

Figure 1 presented the average waiting time for surgery in months among the different special needs patients. The figure indicated that ADHD patients waited the longest for surgery, with an average of 14.29 months, while ASD patients had the shortest waiting time, with an average of 9.29 months.

Table 2 presented the comparison of surgery duration among different special need types. The mean surgery duration was higher in participants with ADHD (229.07 ± 119.92 min), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.771). However, for patients with ASD, the surgery duration was significantly lower (180.17 ± 95.41 min) compared to those without ASD (224.25 ± 101.96 min, p = 0.006). Patients with ID and Epilepsy had higher surgery times than other patients, but the differences were not statistically significant (226.48 ± 104.92 and 221.68 ± 111.03 min, respectively).

Waiting time from screening for different special type needs patients was presented in Table 3. Patients with ADHD had waited longer (14.29 + 16.316 months) than patients with other special needs but the duration of waiting was not statistically significant (p-0.354). However, patients with ASD (9.29 + 12.98 months), ID (9.52 + 12.42 months) and Epilepsy (10.05 + 11.262 months) had slightly less waiting duration than other special needs but there was no significant difference between these duration (P 0.100, 0818, 0.745 respectively).

Figure 2 provided a comparison of existing medical conditions with surgery waiting time in months. Patients with ADHD experienced the longest waiting time, averaging 14 months compared to others special needs adult patient whereas other patients with no known medical conditions had similar waiting times, averaging around 10 months.

There was a statistically significant correlation between the age of patients and surgery duration (p-0.040), however the correlation between them was very weak and positive (r = 0.142) (Table 4).

Figure 3 showed that there is a slight tendency for surgery duration to increase with an increase in patient age, but the relationship is not strong because points are likely widely dispersed, without forming a clear, tight linear pattern.

Discussion

Uncooperativeness of special needs patients during their dental treatment imposes challenges for care providers. Literature has documented that patients with special healthcare needs (SHCN) are less cooperative14. Hence, to treat SHCN patients, special arrangements are often required, including the availability of general anesthesia services in dental clinics. These services are not usually available in all dental clinics, and only a few clinics possess these features, which causes delays in providing treatment to SHCN patients. Therefore, the waiting time from screening to treatment for SHCN patients who visited xxx Dental Hospital was studied in this research.

There were 210 SHCN patients treated during the study period. All patients received full-mouth rehabilitation and thus required general anesthesia to perform the procedure. Due to the necessity of GA for all these patients, the long waiting time from screening to treatment was evident, with an average of 10 months. Several international studies have reported similarly prolonged waiting periods for dental treatment under general anesthesia in special needs populations. For example, in a French cohort study, preschool children with syndromic or cardiac conditions experienced average waiting times up to 6.3 months; school-age children with syndromic diseases waited up to 45.5 months, while otherwise healthy children waited approximately 1–3 months15,16. In a Moroccan hospital-based study of children with special needs, the average wait time was 7.6 ± 4.2 months, attributed to limited qualified personnel and OR availability17. Similarly, Swiss data reported mean intervals of 32 weeks (8 months) between GA preassessment and treatment, with delays driven by administrative approvals and insufficient staffing18.

This waiting time varied according to the type of special needs, with ADHD patients experiencing the longest waiting time, while ASD patients had the shortest waiting time compared to other types of special needs. The variation in waiting time could be due to the behavioral complexities associated with different types of special needs, which require additional treatment and sedation planning10. While the protocols for inducing general anesthesia and performing dental rehabilitation are largely consistent across these patient groups, the differences in waiting time likely reflect factors beyond the actual surgical procedures. For ADHD patients, behavioral management challenges and the need for more intensive preoperative assessment may have led to longer delays in scheduling and coordinating treatment. Conversely, ASD patients at our center typically had more structured behavioral support and caregiver engagement, potentially facilitating more streamlined preoperative planning and faster scheduling. Therefore, while the treatment protocols themselves were similar, these logistical and behavioral considerations likely contributed to the observed differences in waiting time and surgery duration.

Studies have evaluated and reported the obstacles faced by special needs patients in obtaining dental treatment. A study published by Williams et al. from Michigan evaluated the barriers faced by special needs patients in accessing dental treatment. The study reported that finding a dentist willing to treat special needs patients was the most common barrier, followed by financial limitations³. Similarly, a study from Saudi Arabia also evaluated the barriers encountered by special needs patients in accessing dental facilities. The study found that physical accessibility to dental facilities was the most common barrier. Moreover, affordability and the lack of skills or knowledge among dental care providers were also listed as barriers to receiving dental treatment8. Other studies have reported similar findings, where the limited availability of operating rooms and a shortage of trained professionals were marked as obstacles for special needs patients in receiving dental treatment3,9.

Some other studies have reported the perspectives of dentists, in which a high proportion of practitioners felt unqualified to treat patients with special needs due to the difficulty in clinical management and communication with such patients19,20. However, difficulty in obtaining timely dental treatment results in poor dental outcomes, leading to an increased prevalence of caries and a greater need for restorative care21,22.

This study was a single-center study, which was one of its limitations. Additionally, this study was limited to analyzing surgery waiting time and surgery duration; factors associated with these two variables were not studied in detail. Patients’ feedback was not determined after the completion of treatment, nor were the hurdles faced in reaching the treatment clinic. However, the sample size of the study was sufficient to determine the waiting time before surgery and the variation in surgery duration due to different types of special needs patients. The findings help generalize the average waiting time for special needs patients from getting an appointment to undergoing surgery.

Conclusion

This study highlighted that the long waiting time to receive dental treatment was a critical challenge for patients with special needs visiting the dental hospital at King Saud University. Although the specific reasons for these delays were not directly assessed in this study, it is recognized that various factors, including facility-related limitations, availability of skilled providers, and socioeconomic circumstances, may contribute to these barriers as suggested by prior research. Future studies are recommended to explore these potential barriers in detail to inform strategies for improving access and reducing waiting times for this vulnerable population.

Future recommendations

Improving dental care access for individuals with special healthcare needs (SHCN) requires practical, well-supported solutions. One key step is to provide dentists with better training, especially in managing patient behavior and using sedation when necessary. This kind of education has been shown to boost dentists’ confidence and their readiness to treat SHCN patients23. Another important approach is to increase access to general anesthesia services by allocating more operating room time and hiring additional specialized staff. Research from Ontario revealed that many patients with complex medical conditions had to wait over three months for dental procedures under general anesthesia, underlining the need for better planning and resources24. By investing in these kinds of reforms, healthcare leaders can help make dental care more accessible and fairer for some of the most vulnerable members of society.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Gondlach, C., Catteau, C., Hennequin, M. & Faulks, D. Evaluation of a care coordination initiative in improving access to dental care for persons with disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (15), 2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152753 (2019).

Al-Shehri, S. A. M. Access to dental care for persons with disabilities in Saudi Arabia (caregivers’ perspective). J. Disabil. Oral Health. 13 (2), 51–61 (2012).

Williams, J. J., Spangler, C. C. & Yusaf, N. K. Barriers to dental care access for patients with special needs in an affluent metropolitan community. Spec. Care Dentist. 35 (4), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12114 (2015).

Balkaran, R., Esnard, T., Perry, M. & Virtanen, J. I. Challenges experienced in the dental care of persons with special needs: a qualitative study among health professionals and caregivers. BMC Oral Health. 22 (1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02183-6 (2022).

Pecci-Lloret, M. R., Pecci-Lloret, M. P. & Rodríguez-Lozano, F. J. Special care patients and caries prevalence in permanent dentition: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (22), 15194. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215194 (2022).

Mandić, J. et al. Oral health in children with special needs. Vojnosanit Pregl. 75 (7), 675–681. https://doi.org/10.2298/VSP160216335M (2018).

Brown, L. F., Ford, P. J. & Symons, A. L. Periodontal disease and the special needs patient. Periodontol 2000. 74 (1), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12196 (2017).

Alfaraj, A. et al. Barriers to dental care in individuals with special healthcare needs in qatif, Saudi arabia: a caregiver’s perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 15, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S283942 (2021).

Alumran, A. et al. Preparedness and willingness of dental care providers to treat patients with special needs. Clin. Cosmet. Investig Dent. 10, 231–236. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCIDE.S178680 (2018).

Barry, S., O’Sullivan, E. A. & Toumba, K. J. Barriers to dental care for children with autism spectrum disorder. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 15 (2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40368-013-0063-9 (2014).

Jo, T. M., Ying, C. C., Ab-Murat, N. & Rohani, M. M. Oral health behaviours and preventive dental care experiences among patients with special health care needs at special care dentistry clinic, university of Malaya. Ann. Dent. Univ. Malaya. 25 (1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.22452/adum.vol25no1.4 (2018).

Kagihara, L. E., Huebner, C. E., Mouradian, W. E., Milgrom, P. & Anderson, B. A. Parents’ perspectives on a dental home for children with special health care needs. Spec. Care Dentist. 31 (5), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-4505.2011.00206.x (2011).

Seid, M., Sobo, E. J., Gelhard, L. R. & Varni, J. W. Parents’ reports of barriers to care for children with special health care needs: development and validation of the barriers to care questionnaire. Ambul. Pediatr. 4 (4), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1367/A03-165R.1 (2004).

Chavis, S. E., Wu, E. & Munz, S. M. Considerations for protective stabilization in community general dental practice for adult patients with special healthcare needs: a scoping review. Compend Contin Educ. Dent. 42 (3), 134 (2021).

Badre, B., Serhier, Z. & El Arabi, S. Waiting times before dental care under general anesthesia in children with special needs in the children’s hospital of Casablanca. Pan Afr. Med. J. 17, 298 (2014).

Jockusch, J., Sobotta, B. A. & Nitschke, I. Outpatient dental care for people with disabilities under general anaesthesia in Switzerland. BMC Oral Health. 20 (1), 225 (2020).

Schulz-Weidner, N. et al. Dental treatment under general anesthesia in pre-school children and schoolchildren with special healthcare needs: a comparative retrospective study. J. Clin. Med. 11 (9), 2613 (2022).

Boehmer, J., Stoffels, J. A., Van Rooij, I. A. & Heyboer, A. Complications due to the waiting period for dental treatment under general anaesthesia. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Tandheelkunde. 114 (2), 69–75 (2007).

Hannequin, M., Moysan, V., Jourdan, D., Dorin, M. & Nicolas, E. Inequalities in oral health for children with disabilities: a French National survey in special schools. PLoS One. 3 (6), e2564. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002564 (2008).

Leal Rocha, L. & Vieira de Lima Saintrain, M. Pimentel gomes Fernandes Vieira-Meyer A. Access to dental public services by disabled persons. BMC Oral Health. 15, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-015-0026-5 (2015).

Shah, A. et al. Oral health status of a group at a special needs centre in alkharj, Saudi Arabia. J. Disabil. Oral Health. 16 (3), 79–85 (2015).

Isola, G. et al. The effect of a functional appliance in the management of temporomandibular joint disorders in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Minerva Stomatol. 66 (1), 1–9 (2017).

Dao, L. P., Zwetchkenbaum, S. & Inglehart, M. R. General dentists and special needs patients: does dental education matter? J. Dent. Educ. 69 (10), 1107–1115 (2005).

Adams, A., Yarascavitch, C., Quiñonez, C. & Azarpazhooh, A. Use of and access to deep sedation and general anesthesia for dental patients: a survey of Ontario dentists. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 83 (h4), 1488–2159 (2017).

Funding

No funding was necessary for the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bahiah Abdulaziz Al Askar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. Fatima Yahya AlBishry: Data Curation, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft. Nawaf Munawir Alotaibi: Supervision, Project Administration, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing, Corresponding Author. Abdulaziz Alzaben: Data Collection, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft. Sultan Mohammed Albishi: Resources, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing. Abdulrhman Ahmed Almajed: Data Collection, Validation, Writing – Original Draft. Faisal Saleh Alammari: Formal Analysis, Statistical Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Amal Saud Albarrak: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Askar, B.A., AlBishry, F.Y., alotaibi, N.m. et al. Experience of special care patients receiving dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia at King Saud University Dental University Hospital. Sci Rep 15, 33493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16763-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16763-2