Abstract

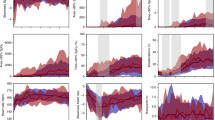

The current standard of care for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) screening eye examinations, binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO), is associated with discomfort and stress in infants. In this study, we compared pain scores and vital signs during examination with BIO and non-contact laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI). Preterm neonates underwent retinal exam with BIO and LSCI during ROP screening. Infant stress was scored using the Neonatal Pain, Agitation, and Sedation Scale (N-PASS), and collected with vital signs, before, during, and after eye examination. Seventy-one infants with gestational ages 22–32 weeks and birthweights 400–1900 g underwent 196 BIO examinations and 101 LSCI examinations. N-PASS scores during BIO were significantly higher than LSCI (8.8 vs. 3.7, p < 0.0001). Maximum heart rate was significantly higher during BIO compared to LSCI (182 ± 19 beats per minute vs. 175 ± 20 beats per minute, p = 0.008). Minimum oxygen saturation was significantly lower during BIO compared to LSCI (83 ± 12% vs. 86 ± 10%, p = 0.035). After BIO, vital sign instability remained for 30 s, whereas vital signs returned to baseline after LSCI. We found lower pain scores and more stable vital signs during LSCI compared to BIO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) screening examinations are essential for preventing blindness among preterm infants1. The current standard of care for screening, binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO), allows for a fast, direct assessment of all zones of the retina. However, BIO is commonly performed with intense illumination, an eyelid speculum, and scleral depression2, which has been shown to cause pain and stress in preterm infants3. Modern imaging using non-contact and non-illuminating devices may provide a gentler method for screening, while also providing an opportunity for a wide-field view of the retina, longitudinal documentation, and comparison4,5.

Although the sensitivity and specificity of emerging imaging tools in accurately detecting and assessing ROP severity is of utmost importance, optimizing comfort in fragile preterm infants is also a concurrent priority. Infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) unfortunately endure cumulative pain from clinical procedures, such as frequent heel pricks, arterial and venous punctures, nasopharyngeal suctioning, and surgery6. Thus, baseline infant pain and stress during standard eye examinations must be well understood, and novel imaging tools must be similarly assessed7,8.

Pain and stress scoring scales monitor infant behavioral responses during different types of eye exams and imaging techniques, such as BIO, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and fundus photography (using Optos, Pictor, and RetCam cameras)9,10,11. Universally, the evidence demonstrates that non-contact methods of OCT and fundus photography are associated with less stress than BIO4,11. The association between infant stress and full contact fundus photography in the literature is inconclusive due to mixed results among studies, with some studies finding an association with less stress during retinal imaging than BIO12,13 and others finding an association with more stress during retinal imaging than BIO9,14,15.

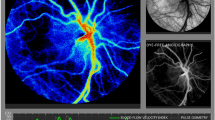

Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) is a novel wide field optical imager that allows visualization and quantification of retinal blood flow16. LSCI captures the rate of motion and resulting blur created by red blood cells as they travel through retinal vasculature under laser illumination17. In diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma studies, LSCI has demonstrated significant differences in ocular blood flow patterns between diseased and healthy eyes by analyzing blood flow in the optic disc and retinal vessels18,19. Increased retinal blood flow underlies the pathogenesis of ROP and thus this supports the potential clinical utility in measuring blood flow velocities to detect and stage ROP severity. Although LSCI technology has not been clinically validated for ROP, growing evidence supports the beneficial use of additional imaging with LSCI in ROP clinical applications20,21,22. LSCI’s blood flow data are potential biomarkers for both high-risk and low-risk ROP. Clinical care may evolve with novel LSCI-based information such that clinicians can identify high-risk progression earlier to enhance secondary prevention. Conversely, we may also better identify low-risk eyes and better understand which infants that can safely be followed with fewer screening eye exams.

Given the particularly delicate and vulnerable population at risk for ROP, understanding the infant experience during LSCI is crucial as we initiate clinical trials to evaluate this potential screening device23. LSCI is designed non-contact and does not require bright light, eyelid speculum, scleral depressor, or pupillary dilation. Thus, we hypothesized that infants may experience less pain and stress during LSCI compared to standard ROP examinations using BIO. The purpose of this study was to prospectively compare vital signs, adverse events, and validated pain scores between BIO and LSCI eye examinations.

Methods

This prospective, non-randomized, non-masked descriptive study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the requirements of the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Written informed consent was obtained from parents of all infants for imaging and study participation. Participants were recruited from April 2022 to September 2023.

Subjects

Preterm infants with a gestational age ≤ 30 weeks, or birthweight ≤ 1500 g, or infants with gestational age > 30 weeks and birthweight 1500–2000 g with a history of clinical instability deemed by the neonatologist to be at risk for ROP, were eligible to participate in this study. All subjects were inpatients in the NICU at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Exclusion criteria were infants with previous intraocular surgery (for example, intravitreal injection or laser), a diagnosis of a major congenital anomaly or genetic syndrome, hemodynamic instability, or surgical procedure under general anesthesia during the 24 h prior to ROP screening exam.

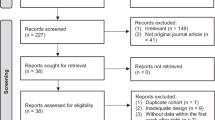

Recruitment

Parents of eligible infants were invited to participate and provided with verbal and written education on ROP and the study protocol. Parents that wished to participate provided written informed consent for one of the following two options, according to their preference: (1) vital signs and behavior assessment during standard BIO exam only, or (2) vital signs and behavior assessment during paired BIO exam and LSCI exam (performed immediately sequential). Approximately half of the cohort opted to receive only BIO exams (n = 36 infants, 196 exams), while the other half opted to receive dual imaging (BIO + LSCI) (n = 35 infants,101 exams).

Study protocol: prior to eye examination

Dilation was performed on the day of ROP screening using topical eye drops (combination cyclopentolate 0.2%/phenylephrine 1%) approximately 60 min prior to the eye exam.

Vital signs including heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), and oxygen saturation (SaO2), were collected from subjects for 30 s before the examination. Blood pressure (BP) was measured once prior to examination. The 30 s pre-examination vital signs were recorded before any movement of the infant, touch, or instillation of proparacaine drops to capture a true baseline. Respiratory device type and fraction of inspired oxygen were recorded during the baseline vital signs video monitoring.

Baseline pain scores were also collected during the 30-second baseline monitoring. A trained study team member graded the neonate’s pain based on the Neonatal Pain, Agitation and Sedation Scale (N-PASS)24. The N-PASS is a validated neonatal stress and pain assessment tool that calculates a composite score that ranges from 0 (no pain) to 13 (maximum pain) based on 7 items using 4 behavioral indicators, 4 physiological indicators (HR, RR, BP, SaO2), and 2 contextual indicators (gestational age and sedation)24,25. The behavioral indicators (crying/irritability, behavioral state, facial expression, and extremities tone) were reported by the nurse assisting with the eye exam and recorded by a study team member. Vital signs monitoring commenced continuously during the entire exam duration and 30 s post-examination by video recording the vital signs monitor.

After the pre-examination vital signs recording, the infant was swaddled and positioned in the bed with a 10-degree wedge placed under the head and shoulders. (Fig. 1d) Topical proparacaine 0.5% was instilled approximately 15 s prior to initiation of eye exam sequence with paired LSCI and BIO, or BIO only.

Study protocol: eye examination

Patients remained in their crib or isolette for the duration of the exam. No changes were made to oxygen support during the exam. N-PASS pain scores were assessed during the first 60 s of each eye exam (LSCI and BIO). Vital signs monitors provided HR, RR, and SaO2 continuously for the entire duration of each eye exam. BP was not cycled during or after eye examination due to concern that the cuff inflation would disturb the infant and impact the N-PASS score or other vital signs.

Eye exams were performed using the investigational LSCI XyCAM NEO Gen 1 System (Vasoptic Medical Inc. Columbia, MD) followed by BIO using the All Pupil II LED Convertible Slimline Wireless (Keeler, Malvern, PA) ophthalmoscope. The XyCAM NEO Gen 1 System leverages the imaging unit of the FDA-cleared XyCAM RI and is mounted on a wheeled floor-standing articulating arm for mobile bedside imaging in supine neonatal patients. (Fig. 1e) During an imaging session, a near-infrared laser (peak wavelength of 785 mm) is centered on the optic nerve head and a high frame-rate image is captured for six seconds. Software outputs a waveform representing peaks and dips in pulsatile retinal blood flow, velocity metrics quantifying blood flow dynamics, and a pseudo-color heatmap.

If the infant received the paired LSCI and BIO sequence, thirty seconds of post-LSCI exam and pre-BIO exam vital signs were continuously collected. The start of the LSCI exam was denoted by opening of the eyelids with gloved fingers (Fig. 1b) or cotton swabs. The start of the BIO exam was denoted by placement of the Alfonso eyelid speculum. The end of the respective exam was verbally indicated by the examiner when the speculum or fingers were removed from the eyelid, no more than 15 min after the start of exam.

Photographs of eye examination using laser speckle contrast imaging in preterm infants. (A) Side view demonstrating relationship between eye and camera utilizing a noncontact approach; (B) side view, demonstrating standard examiner approach to fingertip eyelid opening; (C) cranial view, demonstrating the optimal head position relative to camera for optic nerve centration in the right eye; (D) top-down view demonstrating parallel alignment of camera with infant body; (E) view of the bedside room set-up and equipment. The parents of the infant in these photos gave written consent for use of these photographs in scientific publication.

Neonatal vital sign events

While there are no standardized reference ranges for neonatal vital signs, normal limits for preterm infants for HR ranges from 85 to 205 beats per minute (BPM)26, RR ranges from 30 to 60 breaths per min (BrPM)26,27 and SaO2 is generally maintained at ≥ 89%.28,29 Vital sign events were defined for bradycardia (any isolated decline in HR ≤ 100 BPM, any duration of time), tachycardia (any isolated rise in HR ≥ 200 BPM, any duration of time), oxygen desaturation (< 88% for ≥ 15 s), and apnea (RR = 0 BrPM for ≥ 15 s). By reviewing the vital signs monitor, including alarms that sounded during the exam, a study team member collected the presence or absence and frequency of adverse events.

Statistical analysis

R version 4.2.1 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) were used to perform statistical analyses. Primary variables of interest included N-PASS scores, HR, RR, SaO2, and BP. Confounding variables included sex, race, ethnicity, gestational age, birth weight, post-menstrual age, and respiratory support. Logistic regression with mixed models was used to compare the means of the maximum and minimum values of the N-PASS scores and vital signs while controlling for potential confounders. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the medians of the N-PASS scores while controlling for repeat measures. A paired students t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables and a Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric variables, before, during, and after exams. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Infant demographics and clinical features

Seventy-one infants with gestational ages of 26.8 ± 2.5 weeks and birthweight of 901 ± 329 g were enrolled. At the time of BIO and LSCI examination, the infants had a post-menstrual age between 30.7 and 53.9 weeks (Table 1). The cohort included 47.9% female infants, 45.1% Black infants, 38.0% White infants, and 16.9% of infants identified as “Other” race. Ethnicity included 19.7% Hispanic infants. Most infants (75.5%) required some respiratory support, with the most common type being positive airway pressure. The duration of LSCI was 10.3 min compared to 1.6 min for BIO. The combined LSCI + BIO examination took 12.4 min (due to 0.5 min recovery between exams). Locating the optic disc, focusing the image, and software processing speed for 2 images per eye contributed to the longer exam duration for LSCI.

Vital signs, adverse events, and pain scores during eye exams

There was no statistical difference in baseline vital signs (HR, BP, RR, and SaO2) between the two groups. There was a significant difference in HR, RR, and SaO2 during and post-examination when comparing BIO and LSCI. Deviations from baseline for HR and SaO2 were also significantly different post-examination for BIO (p = 0.01, 0.04) compared to LSCI (p = 0.6, 0.5). Blood pressure was not cycled during exams so only baseline values are available (Table 2).

Tachycardia occurred more frequently during BIO exam compared to LSCI (16% compared to 3%, p < 0.0001). No apnea events were noted during either exam type. There were no significant differences in bradycardia or oxygen desaturation events between LSCI and BIO (Table 3).

Comparison of the N-PASS scores demonstrated pain to be significantly lower during LSCI compared to BIO (8.8 vs. 3.7, p < 0.0001). Sub-scores for behavioral, physiologic, and contextual indicators of pain were also significantly lower during LSCI compared to BIO, indicating that the tachycardia seen during BIO was not the only contributing factor for higher stress scores (Table 4).

Comparison of Infants Receiving BIO Alone Vs. BIO After LSCI

In this cohort, 36 infants (196 exams) received BIO alone and 35 infants (101 exams) received BIO following LSCI. In order to assess whether BIO after LSCI was more disruptive or painful than BIO alone, pain scores and vital signs were stratified by BIO alone vs. BIO after LSCI. The mean NPASS pain score for BIO after LSCI was 8.8 ± 2.2 (range 3.0–12.0), compared to 8.9 ± 2.0 (range 3.0–12.0) for BIO alone (p = 0.76). There was no statistical difference in baseline vital signs (HR, BP, RR, and SaO2) nor pain scores between BIO alone and BIO after LSCI (p > 0.05). Multi-variable regression analysis of exam type (BIO vs. LSCI), order of exam (BIO vs. BIO + LSCI), and number of exams found that only the exam type (BIO vs. LSCI) significantly predicted pain score (p < 0.0001). Order of exam and number of exams did not show a statistically significant association with pain score (p = 0.78 and p = 0.30, respectively).

Discussion

This is the first study comparing validated N-PASS pain scores and vital signs during LSCI and standard ROP screening using BIO. We found that pain scores were significantly higher during BIO compared to LSCI. Individual sub-scores of the total composite score for N-PASS, such as those for extremity tone, behavioral state (arching, kicking), and crying, were also lower for LSCI when compared to BIO. The N-PASS is a highly regarded pain scale, which has shown greater nursing preference, higher mean scores for utility30 and better discrimination of acute procedural pain compared to other pain scales25. Furthermore, the N-PASS is validated for use in preterm infants24 with excellent inter-rater reliability with training and good internal consistency8,25. Cry, behavioral state, and extremity tone were easily classified in swaddled infants with respiratory support receiving eye exams. Previous similar studies used the CRIES pain score to assess neonatal pain in ROP cohorts4 but we opted not to select this pain scoring system due to concerns about lack of validation in premature infants8,31. Previous studies have also utilized PIPP-R2, however its use was limited because it was often impossible to score during eye exams when the examiner’s hands and infant’s respiratory hardware obscured the behavioral scorer’s view while grading features of brow bulge, eye squeeze, and nasolabial furrow.

Vital signs results demonstrate mean HR was significantly higher and mean SaO2 was significantly lower during BIO compared to LSCI. While the mean values for HR and SaO2 showed a statistically significant difference between BIO and LSCI, the difference is small and therefore not clinically significant (SaO2 of 83% during BIO compared to 86% during LSCI is a difference of only 3% SaO2). For all vital sign events, only tachycardia occurred with significantly greater frequency during BIO than LSCI. There were also persistent deviations in vital signs from baseline for BIO, which also differed from LSCI. HR and SaO2 were less likely to return to baseline values within 30 s after concluding the BIO exam compared to the LSCI exam. Among most infants receiving the BIO examination only, the vital signs did not return to baseline after 30 s. Therefore, in retrospect, we found that the 30-second post-exam period is too short to adequately assess for recovery back to baseline because we did not monitor vital signs for more than 30 s after the conclusion of either exam. RRs were similar during LSCI compared to during BIO; however, after the exam was complete, LSCI RRs returned to baseline within 30 s, while they remained abnormally high or low following BIO. Overall, these findings support the hypothesis that LSCI is less stressful than BIO, but both exams are tolerated by the preterm neonate.

Our findings were consistent with previous studies that demonstrated more favorable pain profiles and more stable vital signs during non-contact methods of eye examination in preterm neonates compared to BIO4,11. This was the first study to assess neonatal stress during LSCI. Given recent trends in ROP literature, blood flow assessment is a key area of interest and progress, likely due to increased availability of novel tools such as adaptive optics, OCT angiography, color doppler imaging, and LSCI20,32,33.

LSCI may offer considerable benefit to future advances in ROP diagnosis and management, given our growing understanding that retinal perfusion status plays a critical role in disease progression. Furthermore, LSCI’s gentle approach provides ocular imaging with less pain and more stable vital signs as added motivation to explore the clinical utility of this technology.

Two fundamental differences between LSCI and BIO made direct comparison challenging. First, LSCI duration is 5 times longer than BIO. The longer exam offers more opportunity to identify vital sign disruption. This would bias the study in favor of finding more vital sign abnormality with LSCI than BIO, which reinforces our results. Next, BIO requires speculum use and LSCI does not. This a reality of eye examination techniques that use bright visible light. Given that speculum use is standard for our ROP screening team, this was part of the overall BIO experience and therefore appropriate to include. Eyelid speculum use has been shown to induce pain2 and likely contributed to increased pain during BIO. ROP screeners who do not use a speculum may have lower pain scores and less vital signs disruption than we identified in this cohort.

Several limitations are notable in this study. First, the order of LSCI and BIO was not randomized among infants. The BIO exam was always performed after LSCI. We initially randomized the exam order in a pilot study of 10 subjects not included in this dataset. However, we were unable to begin the LSCI exam soon after BIO exam due to persistent unstable vital signs following BIO. This resulted in longer duration of time in the infant’s room, or cancelling the LSCI exam due to concern about infant stability. Randomizing the order of the exams may provide more robust conclusions, however, it is not feasible to wait for the neonates to return to baseline vitals after BIO in the clinical context of rounding in the NICU. Many infants received “BIO-only” exams, due to parent preference, so we had a subgroup that received BIO as their first and only exam, rather than LSCI + BIO. This subgroup did not have significantly different N-PASS scores nor vital signs than the cohort who received BIO following LSCI. This finding furthermore suggests that the non-contact LSCI exam did not have a carryover effect during BIO exam. Our findings of poor post-exam recovery for BIO exam relative to LSCI supported this aspect of our study design. Non-randomized studies are subject to selection bias and confounding. Regression analysis was able to incorporate confounders (number and order of exams) to estimate their impact on outcome. Results were also stratified by number of examinations to determine the effect of BIO vs. BIO + LSCI to further address potential confounding. Both statistical approaches suggested that the exam type was the only significant predictor of vital signs and pain scores, but it is possible that other important confounders were not collected. Second, motion artifact is well known to impact respiratory monitors and our RR data. Third, BP measurement was via arm cuff, not arterial pressure monitoring, and therefore does not provide real time data. Only a single measurement for BP was taken prior to exam. Fourth, our observers grading pain and vitals could not be masked to the exam type due to the need to observe the infant during the exam to collect data.

The longer duration of LSCI exam was identified in this study, a downside relative to BIO exam. We have found that the examiner learning curve dictates exam duration, and speed comes with examiner experience utilizing LSCI. Also, in the research setting, repeat measures are obtained, which are uncommon in the clinical care setting. Thus, we anticipate shorter duration of LSCI with experienced imagers in the clinical care setting. Nonetheless, the longer duration LSCI exam was better tolerated in terms of pain scores and vital signs, reinforcing our results and the worthwhile advantage of gentler ROP imaging techniques like LSCI. Decreased pain, stable vital signs, and a quick informative examination are the goals of new generation imaging for ROP screening. Our findings suggest that LSCI may bring us one step closer to this goal.

Strengths of the study were prospective design, consistent well-defined exam protocols, relatively large sample size, and controlling for multiple measures per subject using statistical approaches.

Conclusions

In summary, pain levels are significantly reduced among infants receiving non-contact imaging with LSCI compared to BIO. Vital signs are statistically more stable during LSCI compared to BIO, but the difference in vital signs is not clinically significant. Although LSCI offers a non-contact, less painful approach to ROP assessment, there is not yet evidence demonstrating that LSCI allows the ophthalmologist to assess all zones as effectively, efficiently, and reliably as is currently achieved with the BIO. Our findings support the safety for further research in larger trials in an extremely fragile and sensitive neonatal population to understand if LSCI’s objective analysis of retinal vascular parameters provides clinically useful data during ROP screening in the future.

Data availability

We affirm our commitment to ensuring transparent and responsible handling of the data presented in this clinical research paper. Access to the primary dataset generated from this study will be made available upon reasonable request to J.L.A (jalexander@som.umaryland.edu). Data has been made available to the Editorial Board Members. The analysis was conducted rigorously, adhering to established methodologies, and any interpretations are based solely on the findings derived from the data.

References

Sabri, K., Ells, A. L., Lee, E. Y., Dutta, S. & Vinekar, A. Retinopathy of prematurity: A global perspective and recent developments. Pediatrics 150, 3 (2022).

Mataftsi, A. et al. Avoiding use of lid speculum and indentation reduced infantile stress during retinopathy of prematurity examinations. Acta Ophthalmol. 100, 128–134 (2022).

Onuagu, V., Gardner, F., Soni, A. & Doheny, K. K. Autonomic measures identify stress, pain, and instability associated with retinopathy of prematurity ophthalmologic examinations. Front. Pain Res. 3, 1032513 (2022).

Mangalesh, S. et al. Preterm infant stress during handheld optical coherence tomography vs binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy examination for retinopathy of prematurity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 139, 567–574 (2021).

Hoyek, S. et al. Identification of novel biomarkers for retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants by use of innovative technologies and artificial intelligence. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 97, 101208 (2023).

Luo, F. et al. Evaluation of procedural pain for neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit: A single-centre study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 7, e002107 (2023).

Mangalesh, S. & Toth, C. A. Preterm infant retinal OCT markers of perinatal health and retinopathy of prematurity. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1238193 (2023).

Glenzel, L., do Nascimento Oliveira, P., Marchi, B. S., Ceccon, R. F. & Moran, C. A. Validity and reliability of pain and behavioral scales for preterm infants: A systematic review. Pain Manag. Nurs. 24, e84–e96 (2023).

Fung, T. H. M., Abramson, J., Ojha, S. & Holden, R. Systemic effects of optos versus indirect ophthalmoscopy for retinopathy of prematurity screening. Ophthalmol. Sci. 125, 1829–1832 (2018).

Balasubramanian, T. et al. Neonatal vital signs using noncontact laser speckle contrast imaging compared to standard care in retinopathy of prematurity screening. J. AAPOS 26, e38–e39 (2022).

Prakalapakorn, S. G. et al. Non-contact retinal imaging compared to indirect ophthalmoscopy for retinopathy of prematurity screening: Infant safety profile. J. Perinatol. 38, 1266–1269 (2018).

Moral-Pumarega, M. T. et al. Pain and stress assessment after retinopathy of prematurity screening examination: Indirect ophthalmoscopy versus digital retinal imaging. BMC Pediatr. 12, 132 (2012).

Mukherjee, A. N., Watts, P., Al-Madfai, H., Manoj, B. & Roberts, D. Impact of retinopathy of prematurity screening examination on cardiorespiratory indices. A comparison of indirect ophthalmoscopy and retcam imaging. Ophthalmol. Sci. 113, 1547–1552 (2006).

Wade, K. C. et al. Safety of retinopathy of prematurity examination and imaging in premature infants. J. Pediatri. 167, 994–1000e2 (2015).

Dhaliwal, C. A., Wright, E., McIntosh, N., Dhaliwal, K. & Fleck, B. W. Pain in neonates during screening for retinopathy of prematurity using binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy and wide-field digital retinal imaging: A randomised comparison. Arch Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed 95, F146–F148 (2010).

Senarathna, J., Rege, A., Li, N. & Thakor, N. V. Laser speckle contrast imaging: Theory, instrumentation and applications. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 6, 99–110 (2013).

Cho, K. A. et al. Portable, non-invasive video imaging of retinal blood flow dynamics. Sci. Rep. 10, 20236 (2020).

Marino, M. J., Gehlbach, P. L., Rege, A. & Jiramongkolchai, K. Current and novel multi-imaging modalities to assess retinal oxygenation and blood flow. Eye 35, 2962–2972 (2021).

Vinnett, A. et al. Dynamic alterations in blood flow in glaucoma measured with laser speckle contrast imaging. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma. 5, 250–261 (2022).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Decreased ocular blood flow after photocoagulation therapy in neonatal retinopathy of prematurity. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 61, 484–493 (2017).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Ocular blood flow values measured by laser speckle flowgraphy correlate with the postmenstrual age of normal neonates. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 254, 1631–1636 (2016).

Shats, D. et al. Association of speckle-based blood flow measurements and fluorescein angiography in infants with retinopathy of prematurity association of speckle-based blood flow measurements and fluorescein angiography in infants with retinopathy. Ophthalmol. Sci. 4, 100463 (2024).

DeBuc, D. C., Rege, A. & Smiddy, W. E. Use of XYCAM RI for noninvasive visualization and analysis of retinal blood flow dynamics during clinical investigations. Expert Rev. Med. Devices. 18, 225–237 (2021).

Hummel, P. A., Puchalski, M. L., Creech, S. D. & Weiss, M. G. N-PASS: Neonatal pain, agitation and sedation scale-reliability and validity. Pediatr. Res. 53, 456A–457A (2003).

Hummel, P., Lawlor-Klean, P. & Weiss, M. G. Validity and reliability of the N-PASS assessment tool with acute pain. J. Perinatol. 30, 474–478 (2010).

Fleming, S. et al. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years: A systematic review of observational studies. Lancet 377, 1011–1018 (2011).

Alhassen, Z., Vali, P., Guglani, L., Lakshminrusimha, S. & Ryan, R. M. Recent advances in pathophysiology and management of transient tachypnea of newborn. J. Perinatol. 41, 6–16 (2021).

Manja, V., Lakshminrusimha, S. & Cook, D. J. Oxygen saturation target range for extremely preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 332–340 (2015).

Manja, V., Saugstad, O. D. & Lakshminrusimha, S. Oxygen saturation targets in preterm infants and outcomes at 18–24 months: A systematic review. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1609 (2017).

Huang, X. Z. et al. Evaluation of three pain assessment scales used for ventilated neonates. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, 3522–3529 (2018).

Jancova, H. & Pokorna, P. Multimodal pain management in extremely low birth weight neonates after major abdominal surgery. Top. Postop Pain. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.111519 (2023).

Rowe, L. W., Belamkar, A., Antman, G., Hajrasouliha, A. R. & Harris, A. Vascular imaging findings in retinopathy of prematurity. Acta Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1111/AOS.15800 (2023).

Silverman, R. H. et al. Ocular blood flow in preterm neonates: A preliminary report. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 10, 22 (2021).

Funding

Dr. Janet Leath Alexander, corresponding author, received funding from the Maryland Industrial Partnerships (MIPS) Program, under the grant number 7103 (funded in part by Vasoptic Medical, Inc [VMI]), and the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program, under award number R43EY030798. We also acknowledge the support of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, Institute for Clinical & Translational Research (ICTR) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA), grant number UL1TR003098. Our work was also supported by the Little Giraffe Foundation and the National Eye Institute (NEI) of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23EY03252. Ms. Urjita Das, Ms. Euna Cho, Ms. Tara Balasubramanian, Ms. Taylor Kolosky, Ms. Claudia Wong, Ms. Danielle Sidelnikov, and Mr. Daniel Shats received funding from the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Proposed Research Initiated by Students and Mentors (PRISM) Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, MIPS program, SBIR program, or University of Maryland Baltimore ICTR. The funders played no part in study design, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, manuscript preparation, manuscript review, manuscript approval, or publication decisions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.D., T.B., S.S., O.S., and J.L.A. conceptualized and designed the study. All authors recorded the study data. U.D. and J.L.A. drafted the first manuscript. U.D. conducted the literature search. U.D. and J.L.A. conducted the statistical analysis and interpreted the data. U.D. prepared Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4; Figure 1. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. J.L.A., S.S., O.S., and R.L. supervised the conduct of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. U.D., D.S., D.S., and J.L.A. obtained funding. K.W. was present during every imaging session as the bedside nurse and acquired the photos. R.L. and J.L.A. conducted every laser speckle contrast imaging session and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy exam. All authors approved the submission of this version of manuscript and take full responsibility for the manuscript. We want to thank the NICU nursing staff and providers at the bedside for supporting our research efforts and caring for the infants included in this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Das, U., Cho, E., Balasubramanian, T. et al. Comparing infant pain and stress during retinopathy of prematurity screening using ophthalmoscopy and non-contact imaging. Sci Rep 15, 32771 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16792-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16792-x