Abstract

Climate change is amplifying drought impacts globally, yet conventional drought typology (meteorological, agricultural, hydrological) systematically excludes environmental drought, a critical driver of ecosystem collapse, from multi-index comparative assessments. This omission persists despite evidence that anthropogenic warming exacerbates hydrological non-stationarity and ecological degradation. This study bridges this gap by analyzing meteorological (precipitation), agricultural (vegetation), hydrological (streamflow), and environmental (ecology) droughts. The comparative multi-index approach, developed by this study, employs four indices: the 3-month Standardised Precipitation Anomaly Index (SPAI-3 for meteorological drought), Vegetation Health Index (VHI for agricultural drought), 3-month Standardized Streamflow Index (SSI-3 for hydrological drought), and Environmental Drought Index (EDI for ecosystem water deficit). Drought severity is classified into four tiers (slight to extreme) across 1982–2023, with sub-period analysis (1982–2000 vs. 2001–2023) to isolate climate-change-driven shifts. Considering a rainfed-basin in India (Jaraikela gauging station in the Brahmani River basin), as the study site, results show 170 slight and 127 moderate drought events, spanning over 633 months—evidence of persistent mild-to-moderate water stress. Severe hydrological droughts nearly doubled in frequency and drought-months (10.5% → 21.7%), while severe environmental droughts surged by 65% (31.6% → 52.2%) and now constitute over a third (36.7%) of such events. Moderate meteorological droughts increased by 50% (57.9% → 87.0%), now spanning 100+ months, whereas moderate agricultural droughts halved (100% → 47.8%). Environmental droughts lasted 267 months over 49 events (average > 5 months/event). Severe and extreme droughts, though rarer (35 severe, 3 extreme), covered 153 months. These results underscore environmental drought as a critical but understudied dimension of climate change impacts, with ecological degradation accelerating faster than hydrological stress. Moreover, these findings demonstrate that climate-driven shifts in monsoon patterns disproportionately affect ecological water deficits compared to agricultural systems, where adaptive practices may buffer moderate droughts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Droughts are among the most pervasive natural hazards, impacting 74% of global ecosystems and causing $220 billion in annual agricultural losses1,2. During extended periods of water scarcity, droughts disrupt the hydrological cycle, depleting soil moisture by 15–40% and reducing streamflow sensitivity to precipitation by 20% during prolonged events3,4. This hydrological imbalance jeopardizes crop yields, with drought-driven yield losses affecting 454 million hectares of global cropland (1983–2009) and reducing calorie production by 35% in water-stressed basins2,5. In drought-prone regions like South Asia, rainfed agriculture, which supports 60% of the population, faces 30–50% productivity declines during extreme droughts1,6. Drought-related environmental degradation accelerates soil carbon loss by 15–30% in grasslands and increases wildfire-driven soil erosion by 2–2.5 cm per fire event, exacerbating biodiversity decline7,8. Since 2000, drought frequency has increased by 29% globally, with 150–200% higher likelihood of extreme agricultural droughts at 2 °C warming2,9. Rising temperatures amplify evapotranspiration by 5–15% per 1 °C, intensifying moisture deficits even in humid regions4,10. Regional analyses reveal 87% of South Asia, 72% of Africa, and 64% of Europe now experience decadal “megadroughts” unseen in the past millennium1,11,12. Traditional drought typology (meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological) assessments overlook 40–60% of ecological drought impacts due to inadequate cross-index comparisons, underscoring the need for multi-indicator frameworks9,13.

Recent global research highlights the limitations and sectoral biases of single-index drought analyses, though still widely used for meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and socioeconomic drought typologies, and increasingly for environmental drought (see Table 1; references therein). For meteorological drought, indices like the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)15 and Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI)14 are applied from the United States32 and Europe33 to the Indo-Gangetic plains34, providing key understanding of precipitation anomalies but commonly missing deeper feedbacks from rising evapotranspiration and regional warming. In South Asia, the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)16 improves monsoon deficit detection at grid and basin scales, as recent Indian35 and Chinese36 studies show, yet it cannot alone reveal how rainfall shocks propagate into hydrological or environmental drought. Agricultural drought indices such as the Vegetation Health Index (VHI)22 and Vegetation Condition Index (VCI)21, enabled by satellite data, have transformed crop stress monitoring in Africa’s Sahel37, the Australian wheatbelt38, and semi-arid Indian regions39, correlating with yield variability but struggling to capture underlying meteorological drivers or downstream hydrological deficits, and usually overlooking ecosystem impacts of recurring agricultural failures. Hydrological indices like the Standardized Streamflow Index (SSI)25 and Surface Water Supply Index (SWSI)24 provide real-time monitoring, used in South Africa40, the West-Asia41, and the extratropical Andes Cordillera42, but by focusing on surface water, may miss groundwater depletion or ignore concurrent agricultural, socioeconomic, and resulting environmental drought. Socioeconomic indices such as the Multivariate Standardized Reliability and Resilience Index (MSRRI)26,27 and Standardized Water Supply and Demand Index (SWSDI)30 connect supply–demand imbalances and system resilience to income or municipal reliability, yet struggle to track cascading biophysical droughts underlying these human conditions. Newly implemented environmental drought indices like the Environmental Drought Index (EDI)31,43 in Indian river systems directly quantify ecological water deficits, addressing the inability of conventional typologies to include the environmental and ecological dimension. Thus, comparative analysis of EDI alongside existing meteorological, agricultural, or socioeconomic indices can provide an essential additional perspective in drought severity studies.

While single-index drought assessments have advanced the understanding of specific drought drivers, for example, agricultural drought frameworks explain 60–75% of crop yield variability in water-limited regions44,45, emerging evidence highlights the need for cross-dimensional analyses. Recent work demonstrates that 48% of drought cascades (e.g., meteorological → hydrological → agricultural) remain undetected when indices are applied in isolation46. Hydrological indices like SSI-3, while critical for reservoir management, capture only 32% of drought-induced groundwater depletion in semi-arid basins when decoupled from agricultural and ecological metrics9,47. Similarly, socioeconomic drought frameworks, which correlate water scarcity with 14–29% income loss in agrarian economies1, commonly overlook feedbacks from environmental degradation, such as 2.3× faster soil carbon loss in drought-stressed ecosystems8. Integrative approaches [for example, Zhang & Miao46 reveal that multi-index analyses improve drought early-warning accuracy by 37% compared to single-index methods. However, such studies remain regionally constrained, with only 18% of global drought assessments incorporating environmental or ecological dimensions2,4. Across these diverse cases, it becomes evident that single-index analyses can be highly informative for sector-specific vulnerability or resource management, but are fundamentally limited in resolving the propagation dynamics of drought across sectors, obscuring multi-dimensional risks, and entirely omitting the influence of environmental or ecological stressors unless specifically targeted. Such approaches yield piecemeal or “siloed” understanding, insufficient for holistic analysis, early warning, or adaptation planning in interconnected social-environmental systems. Therefore, the adoption of comparative multiple index drought analysis (which is the key focus of this study) emerges as one of the scientifically robust pathways for capturing the complexity of drought severity, feedbacks, and management priorities in both local and global contexts.

Comparative multi-index analyses are increasingly recognized for their capacity to contextualize drought impacts across meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and the newly considered environmental dimensions, each reflecting unique facets of water scarcity. Large-scale case studies, such as the CHM_Drought dataset for China, demonstrate that cross-index comparisons can elevate drought detection rates by 23–37% in semi-arid regions compared to single-index methods, thereby improving both monitoring accuracy and early warning potential46. Such approaches have been pivotal in regions where drought propagation cascades from meteorological to agricultural and hydrological extremes, viz., an effect documented in the Pearl River Basin, where the coupling and lagged response between meteorological and hydrological droughts reveal the limits of sector-specific indices for capturing basin-wide risk47,48. In India, recent multi-index studies have quantified how meteorological anomalies translate into agricultural losses, demonstrating the combined use of indices such as the meteorological drought index and vegetation health metrics to dissect drought legacies and impacts on crop production under climate change scenarios, as exemplified in the Godavari Basin and across monsoon-dependent regions44,49,50. Research across South Asia increasingly emphasizes the need for cross-dimensional analysis, showing that traditional single-index frameworks may overlook soil moisture deficits critical for agricultural and ecological outcomes6,51. Global syntheses confirm that drought propagation, from meteorological onset to soil moisture deficit and yield reduction, requires a comparative perspective to unravel cascading risk2,52. Moreover, multifractal and cross-sectoral studies have mapped the non-linear amplification of drought severity and impacts, highlighting that ecosystem responses and legacy effects, such as reductions in resilience following sequential drought events, are emergent properties best detected through joint index analysis53. While these efforts have increasingly adopted composite and parallel multi-index frameworks, providing critical advancements in drought diagnosis and policy relevance, they have largely focused on the meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological domains. Systematic side-by-side inclusion of the environmental and ecological perspective, as achieved with the Environmental Drought Index31, remains rare, signaling a pressing need for future work to bridge this gap and deliver truly comprehensive drought risk assessments.

Despite major advances in drought science, fundamental uncertainties persist regarding how different drought types interact, intensify, and propagate across coupled human–natural systems under a changing climate. Most notably, although comparative multi-index frameworks have been developed to capture sector-specific drought expressions, there remains an absence of studies that systematically integrate the environmental dimension, specifically through the side-by-side application of the EDI with conventional meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological indices. Existing research has largely been siloed, with rigorous investigations delineating mechanisms and impacts singularly within meteorological, agricultural, or hydrological domains, while leaving ecological droughts, viz., those affecting ecosystem flows, biodiversity, and environmental resilience, either underrepresented or entirely unaddressed. This omission is increasingly problematic, as mounting evidence suggests that climate change-driven shifts in drought regimes commonly manifest most acutely in environmental systems, yet their detection and management remain hampered by the lack of a unified, cross-dimensional analytic approach. Critical research gaps therefore lie in understanding: (1) how environmental droughts align—or diverge—from droughts of other types in terms of severity, frequency, and persistence; (2) whether unmanaged ecosystems exhibit distinct temporal and severity dynamics compared to managed agricultural or hydrological subsystems; and (3) what asymmetries exist in the propagation and compounding of droughts across sectors, particularly under contemporary climate and land-use pressures. Motivating this inquiry is the urgent need to close the observational and diagnostic gap surrounding environmental droughts, particularly in climate-stressed, data-limited basins where integrated adaptation and conservation strategies hinge on timely, holistic risk appraisal. It is hypothesized that the environmental dimension not only responds differently but may, in fact, accelerate disproportionately during periods of intensified climate variability, revealing vulnerabilities masked by single-type or composite indices. Addressing these research problems might be pivotal for developing cross-sectoral early warning, resilient management practices.

To address the research gaps identified in the present investigation, this study pursues three objectives: (1) to quantify drought severity across four drought types (meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental) using a comparative multi-index methodology, avoiding integrative approaches that obscure sector-specific vulnerabilities; (2) to evaluate 42-year trends (1982–2023) with sub-period analysis (1982–2000 vs. 2001–2023) to isolate climate-change-driven intensification; and (3) to evaluate severity-specific drought occurrences and their frequencies amidst proposing management strategies for a water-stressed basin as a case study. This study applies four indices individually, viz., the Standardized Precipitation Anomaly Index (SPAI), Vegetation Health Index (VHI), Standardized Streamflow Index (SSI), and Environmental Drought Index (EDI), to compare drought responses across systems. The SPAI quantifies meteorological drought through rainfall anomalies, which explain 62–75% of monsoon variability in South Asia1,17. The VHI, a proxy for agricultural stress, correlates with 30–45% of crop yield losses during soil moisture deficits21. Meanwhile, the SSI captures hydrological drought severity, with 1σ streamflow declines (1σ refers to a decline in streamflow equivalent to one standard deviation below the mean), reducing reservoir storage by 18–22% in water-stressed basins4,25. The EDI, a novel metric for environmental drought, addresses ecosystem-specific moisture deficits31. In this study, the term comparative multi-index methodology refers to the parallel analysis of multiple single-factor drought indices, specifically, meteorological (SPAI-3), agricultural (VHI), hydrological (SSI-3), and environmental (EDI), where each index is calculated and interpreted independently. This approach is different from multi-factor or compound drought indices-based methodological investigation, which combines or integrates several indicators into a single composite metric for overall drought assessment. By analyzing these indices in parallel, this comparative multi-index methodology may reveal how drought cascades propagate. Such cross-comparisons equip policymakers with implementable steps, for instance, prioritizing reservoir releases when a severe degree of hydrological and environmental droughts concurrently exceed critical thresholds. The novelty lies in pairing the newly developed EDI with established indices to reveal asymmetries in climate impacts. By contextualizing these dynamics in India’s Jaraikela catchment, a semi-arid region located in the climate-stressed Brahmani river basin, this work provides a replicable template for regions balancing agricultural productivity and ecosystem conservation under anthropogenic warming.

Materials and methodology

Drought analysis approaches

Table 2 (references therein) presents an overview of the four distinct types of drought analyzed in this study: meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental. Each type and the specific index utilized for its assessment are defined briefly and further detailed in the subsequent subsections.

Meteorological Drought Index: SPAI

The SPAI quantifies meteorological drought by analyzing precipitation deviations from long-term climatological norms, facilitating robust cross-regional and temporal comparisons17. Unlike indices that normalize raw precipitation [e.g., Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)], SPAI isolates anomalies before standardization. By isolating deviations from climatology, SPAI disentangles climate change-driven trends (e.g., anthropogenic warming) from natural seasonal cycles, a critical advantage under non-stationarity. The derivation follows this: for the ith year and jth time step (e.g., January), the precipitation anomaly is computed using Eq. (1):

where, \({y}_{i,j}\) represents the precipitation anomaly for the ith year at the jth time step (units: mm); similarly, \({x}_{i,j}\) is the recorded precipitation value for the ith year at the jth time step; \({\overline{x} }_{j}\) denotes the long-term mean precipitation for the jth time step. Critically, no normalization by standard deviation (\({s}_{j}\)) occurs here, distinguishing SPAI from SPI.

Anomalies are standardized by fitting a single probability distribution to the entire anomaly series (y), not individual time steps. This ensures consistent probabilistic interpretation across seasons and years. The t-location-scale distribution is employed due to its ability to model heavy-tailed data and accommodate negative values (common in anomalies), thereby avoiding gamma distribution constraints that limit SPI’s applicability to positive-only precipitation totals. Its probability density function (PDF) is shown in Eq. (2) [see Fig. S1(a) in the supplementary document].

In this equation, μ is the location parameter, σ is the scale parameter (with σ > 0), and ν is the shape parameter (with ν > 0). Parameters are estimated via maximum likelihood using the entire anomaly series, ensuring global standardization.

The SPAI derivation involves two critical transformations: quantile mapping and Z-score conversion. First, precipitation anomalies, computed as deviations from long-term climatological means (Eq. 1), are converted to quantiles (0–1) via the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of a t-location-scale distribution fitted to the entire anomaly series. These quantiles, termed reduced variates, represent the empirical probability of observing a given anomaly magnitude. Second, reduced variates are mapped to standard normal deviates (Z-scores), yielding SPAI values ranging from − ∞ to + ∞. It is expressed as the inverse normal transformation (\({\Phi }^{-1}\)) applied to the t-location-scale CDF of precipitation anomalies, yielding standardized Z-scores, as shown in Eq. (3):

By convention, SPAI < − 1 indicates drought conditions, while SPAI > 1 reflects wetter-than-normal periods (Table 4). This dual transformation ensures comparability across regions and aligns with global drought classification standards. For temporal scalability, SPAI is computed over aggregated periods (e.g., 3-month SPAI-3). It reflects precipitation over a 3-month (M1, M2, …, Mn) rolling window. Here, M₁ = SPAI-3 for January (precipitation from November–January). Similarly, M₂ = SPAI-3 for February (precipitation from December–February) and Mn = SPAI-3 for the nth month.

Agricultural Drought Index: VHI

The VHI assesses agricultural drought by integrating vegetation greenness [Vegetation Condition Index (VCI)] and thermal stress [Temperature Condition Index (TCI)], providing a robust metric for crop health under climatic extremes22. Unlike single-index approaches, VHI accounts for both moisture availability and temperature-driven evapotranspiration, critical for drought propagation in agroecosystems.

-

Calculation of VCI: VCI resolves interpretational challenges of raw NDVI values, which are confounded by regional variations in soil, vegetation type, and climate. Instead of min-max normalization, VCI uses percentile-based scaling to reduce outlier sensitivity. VCI can be calculated using Eq. (4):

$$VCI=\frac{NDVI-{NDVI}_{min}}{{NDVI}_{max}-{NDVI}_{min}}$$(4)where, NDVImax and NDVImin represent the maximum (95th percentile) and minimum (5th percentile) NDVI values observed over a long-term period for the specific region, respectively. This method isolates climatic effects on vegetation by comparing current NDVI to historical extremes, with values near 100 indicating optimal health and near 0 signaling severe stress.

-

Calculation of TCI: TCI captures the temperature-related stress on vegetation, which is essential in monitoring how thermal conditions affect crop health. Since excessive temperatures can exacerbate drought conditions by accelerating moisture loss, TCI inversely correlates temperature changes with vegetation health. TCI is computed using Eq. (5):

$$TCI=\frac{{T}_{max}-T}{{T}_{max}-{T}_{min}}$$(5)where, T is the observed temperature at a given time, and Tmax and Tmin are the maximum (95th percentile) and minimum (5th percentile) over the study period (1982–2023), respectively. High TCI values (e.g., 80–100) reflect cooler, favorable conditions, while low values (e.g., < 40) indicate heat stress.

-

Calculation of VHI: VHI is derived by integrating VCI and TCI, thus providing a composite measure of drought stress based on both vegetation conditions and temperature effects. VHI is calculated using Eq. (6):

$$VHI=\alpha \cdot VCI+\left(1-\alpha \right)\cdot TCI$$(6)where, α is a weighting coefficient that balances the influence of VCI and TCI. Generally, α is set to 0.5, implying equal VCI and TCI contributions. Equal VCI/TCI weighting ensures transparency and reproducibility, critical for policy applications22. The VHI values range from 0 to 100, where lower values suggest drought conditions, while higher values denote healthier vegetation (see Table 4).

Hydrological Drought Index: SSI

The SSI evaluates hydrological drought by adapting the SPI framework15 to streamflow data, providing a normalized metric of water scarcity severity in river basins25. Streamflow data are inherently skewed and bounded (Di ≥ 0), necessitating a gamma distribution for robust modelling (see Fig. S1(b) in the supplementary document). To address zero values (common in ephemeral streams), a shifted gamma distribution (Di + ε, where ε = 0.1 m3/s) is applied. The gamma probability density function (PDF) is defined using Eq. (7):

where k > 0 (shape) and θ > 0 (scale) are estimated via maximum likelihood. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) is then computed using Eq. (8):

CDF values are transformed into standard normal Z-scores (SSI) using the inverse normal distribution as shown in Eq. (9):

where Φ−1 is the inverse standard normal function. SSI values follow a Gaussian distribution [mean (μ) = 0, standard deviation (σ) = 1], enabling uniform interpretation: SSI < − 1.5: Severe hydrological drought, while SSI > 1.5: Exceptionally wet conditions (Table 4). For temporal scalability, SSI is computed over aggregated periods (e.g., 3-month SSI-3). It reflects precipitation over a 3-month (M1, M2, …, Mn) rolling window. Here, M₁ = SSI-3 for January (precipitation from November–January). Similarly, M₂ = SSI-3 for February (precipitation from December–February) and Mn = SSI-3 for the nth month.

Environmental Drought Index: EDI

The EDI, developed by Srivastava and Maity31and applied in Srivastava et al43., serves as a measure to assess environmental drought conditions by identifying periods when water flow requirements for ecological health fall below essential thresholds. Given this, the Minimum In-stream Flow Requirement (MFR) estimation is essential for maintaining the ecological integrity of the riverine ecosystem. This study employs an improved version of Tennant’s method for MFR estimation, as suitably modified to Indian conditions (refer to31). MFR is the minimum flow needed for ecological functions such as habitat preservation and water quality maintenance. Tennant’s method categorizes river eco-status into seven levels based on Mean Annual Flow (MAF) rates, dividing the year into High Flow Season (HFS) and Low Flow Season (LFS) with specific flow thresholds as percentages of the MAF. Streamflow data from 1982 to 2023 were analyzed to estimate MFR, with HFS defined from June to October and LFS from November to May. Using Tennant’s “Good Habitat” descriptor54, flow thresholds were set at 40% of the MAF during HFS and 20% during LFS, with a flushing flow of 200% of MAF for 48–96 h in August. The calculations are shown in Table 3. The study developed a flow hydrograph (Fig. 1a) using the data from columns h and I from Table 3 to visualize streamflow adequacy in meeting ecological needs. If observed SFR exceeds MFR, streamflow is sufficient; if not, it indicates potential ecological impacts.

(a) Observed monthly variation of Streamflow Rate (SFR) against Minimum in-stream Flow Requirement (MFR) for Jaraikela catchment using Tennant’s method. Each month is representative of the mean discharge over the period 1982–2023 (42 years); (b) Categorization of various EDI values based on different levels of drought duration (DDL) and water shortage (WSL), outlining their respective definitions and ranges [developed after Srivastava & Maity31.

Heuristic Method for Developing EDI: The EDI formulation uses a heuristic framework to quantify environmental drought levels. This approach evaluates hydrological and ecological factors, including drought duration, water deficit severity, and ecological flow needs. Months with a negative \(SFR-MFR\) disparity were identified as environmental drought months until the disparity became non-negative. The Drought Duration Length (DDL), indicating consecutive drought months, is calculated using Eq. (10) and categorized using Eq. (11).

DDL values 1, 2, and 3 signify drought episodes (monthly-scale) occurring quarterly, semi-annually, or annually, respectively, with specific durations outlined for each category. A DDL value of 4 denotes a prolonged drought event extending beyond one year.

Water Shortage Level (WSL) was calculated by assessing the most significant water deficit observed during the DDL period. This calculation involved dividing the absolute value of the Largest Water Deficit (LWD) by the maximum value of MFR within the same DDL, as shown in Eq. (12). The resulting WSL value was categorized into four levels based on predefined thresholds (see Eq. 13).

Finally, the EDI value was determined through the integration of the DDL and WSL assessments to evaluate the magnitude of each environmental drought occurrence, as shown in Eq. (14).

The EDI is categorized into four levels: slight (EDI-1), moderate (EDI-2), severe (EDI-3), and extreme (EDI-4). An EDI of 0 indicates a non-drought scenario (see Table 4 and Fig. 1b).

Comparative multi-index methodology

This study advances a comparative multi-index methodology to assess meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental droughts, facilitating systematic evaluation of drought characteristics across distinct systems (see Fig. 2). The approach is applied to a semi-arid catchment (see next section for regional specifics of the study site) using hydrometeorological and ecological data from 1982 to 2023 (detailed in the section on data description), providing a replicable template for climate-vulnerable regions. The 42-year period is bifurcated into two epochs: 1982–2000 (pre-accelerated warming as per IPCC) and 2001–2023 (anthropogenically influenced climate as per IPCC), isolating shifts in drought severity linked to global temperature rise2. This division facilitates the detection of climate-driven trends, such as intensifying hydrological (or any other) droughts or emerging ecological water deficits.

Comparative multi-index methodological flowchart illustrating the progressive sequence of analysis of drought typologies along with the environmental drought framework. Four indices are applied in parallel to compare drought responses; for details on the equations shown in the flowchart, readers are directed to refer to Eqs. (1–3) for SPAI-3, Eqs. (4–6) for VHI, Eqs. (7–9) for SSI-3, and Eqs. (10–14) for EDI.

Four indices are applied in parallel to compare drought responses, namely, SPAI-3: Meteorological drought via 3-month precipitation anomalies (Eqs. 1–3), VHI: Agricultural drought through vegetation health and thermal stress (Eqs. 4–6), SSI-3: Hydrological drought using standardized streamflow (Eqs. 7–9), EDI: Environmental drought quantifying ecosystem water deficits (Eqs. 10–14). Each index is calculated independently, ensuring sector-specific understandings without conflating drivers. For example, SPAI-3 isolates precipitation deficits, while EDI links streamflow declines to habitat degradation. Furthermore, it is imperative to highlight that the present comparative multi-index analyses prioritize subsystem-optimized scales over uniform temporal aggregation, for example, SPAI (3-month) and SSI (3-month) alongside VHI (1-month) and EDI (1-month). Forcing all indices into a single scale (e.g., 3-month) would dilute VHI’s sensitivity to crop stress signals55 and obscure EDI’s capacity to detect abrupt ecosystem disruptions31.

Drought severity is classified into four tiers: Slight, Moderate, Severe, and Extreme. Thresholds are index-specific (Table 4), aligning with World Meteorological Organization (WMO) standards56, https://wmo.int/, accessed July 19, 2025). Frequency and intensity trends are compared across epochs using: (a) Event-wise analysis counting droughts per severity tier annually, and (b) Duration metrics, where average consecutive months under drought were accounted for in comparative analysis. By juxtaposing four indices, this approach reveals asymmetries in drought impacts-e.g., whether agricultural resilience (via VHI) diverges from ecological degradation (via EDI) under warming. The methodology avoids integrative frameworks, preserving sector-specific signals critical for drought-type targeted adaptation. Therefore, developing a composite drought index by integrating the environmental drought index with existing drought typologies becomes a future scope for this investigation.

Study basin and data

Study basin

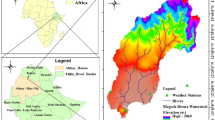

The Jaraikela catchment, part of the Koel River system and a major tributary of the Brahmani River, spans Jharkhand, bordering Chhattisgarh and Odisha (Fig. 3). Covering 10,637 km2, it is one of four sub-basins in the Brahmani River basin, featuring flat and undulating terrain, dense forests, and agricultural fields. Elevation ranges from 198 m at the gauging site to 1,088 m in hilly regions, influencing regional hydrology and biodiversity. It falls primarily within Lohardagga, Gumla, Ranchi, and Paschim Singhbhum (Jharkhand) and Sundergarh (Odisha), extending between latitudes 21° 50′ N to 23° 36′ N and longitudes 84° 29′ E to 85° 49′ E. The sub-humid tropical climate experiences temperature extremes of 47 °C in summer and 4 °C in winter, with annual rainfall between 1000 and 1300 mm, 80% of which occurs during the monsoon (June–September). Rainfed agriculture dominates, utilizing 80% of available water resources. Rapid economic growth and population expansion have heightened concerns about water sustainability. Sinha et al.57 identified high climatic variability, with maximum temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed significantly affecting hydrology. Vandana et al.58 projected declining winter streamflows and recurrent droughts, while Swain et al.59 classified the Brahmani basin as high risk for water scarcity. Studies13,60,61,62,63 highlight worsening water balance issues. Given these challenges—climatic variability, streamflow alterations, and water shortages—the Jaraikela catchment is a critical study site for assessing meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental drought events and their long-term impacts.

(Source: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/get-started/installation-guide/installation-overview.htm)].

Geographic location of the study area, Jaraikela, in Jharkhand, India: Panel (c) highlights the specific study site, Jaraikela, within the local region; panel (b) shows its placement within Jharkhand state; and panel (a) provides a broader view of the site’s location within India [Note: This figure is developed by authors after Srivastava and Maity31 using ArcGIS Version 10.8.2

Data

This study integrates multi-source datasets (Table 5; references are provided therein) to aid a comparative analysis of meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental droughts. The datasets were selected for their spatial–temporal consistency, resolution adequacy, and alignment with index-specific requirements. For meteorological drought (SPAI-3), precipitation data from TerraClimate (1982–2023, 4 km/monthly) were used, which provides global coverage with localized accuracy, critical for detecting seasonal anomalies in semi-arid regions. Unlike coarser datasets, TerraClimate’s 1/12° resolution resolves monsoon variability at catchment scales. For agricultural drought (VHI), vegetation health was assessed using AVHRR NDVI (1982–2000, 0.05°/biweekly) and MODIS NDVI (2001–2023, 1 km/16-day), transitioning post-2000 to integrate MODIS’s improved sensitivity to crop stress. Thermal data for TCI combines TerraClimate (1982–2000) and MODIS LST (2001–2023, 1 km/8-day), with MODIS minimizing cloud contamination through its 8-day composites. Cross-sensor harmonization ensured continuity, with NDVI trends showing < 5% deviation during overlap years (2000–2001). For hydrological and environmental droughts (SSI-3, EDI, India-WRIS daily streamflow data (1982–2023) was used from Jaraikela station. While SSI-3 quantifies water scarcity using standardized streamflow anomalies, EDI applies ecologically informed thresholds (e.g., minimum flow for riparian habitats) to assess environmental drought severity. The dataset’s daily resolution captures rapid hydrological responses to monsoon breaks.

Common spatial–temporal alignment for all datasets (spans 1982–2023), enabled direct cross-era comparisons. Transitions (e.g., AVHRR → MODIS) were timed to satellite availability and validated for consistency. Resolution suitability was checked, in that finer resolutions (e.g., MODIS 1 km) post-2000 address early AVHRR limitations in heterogeneous landscapes. Given the achievement of open access and reproducibility targets, the present investigation was conducted on Google Earth Engine (GEE), enabling script-based replication (Code Availability). Moreover, the datasets’ heterogeneity (point-based streamflow vs. gridded climate data) is resolved through catchment-scale zonal statistics in GEE, ensuring spatial coherence. For example, TerraClimate precipitation pixels intersecting the Jaraikela catchment were averaged to match India-WRIS’s station data, while MODIS NDVI was aggregated to monthly means for VHI computation. Table 5 summarizes dataset attributes.

All datasets underwent thorough quality assurance and pre-processing procedures prior to index computation. The SPAI-3, SSI-3, and EDI datasets were found to be complete for the selected study period, without any missing or spurious entries, owing to the high data integrity protocols enforced by their respective data custodians (Table 5; reference therein). For VHI, which relies on long-term NDVI and temperature series from AVHRR, MODIS, and TerraClimate, minor data gaps, primarily due to persistent cloud cover or sensor dropout, were addressed using a moving window temporal interpolation technique. Additionally, periods of overlapping sensors (e.g., AVHRR-MODIS transition years) were harmonized through cross-calibration and comparison of seasonal trends, ensuring consistency and continuity in the VHI record. Outlier and duplicate checks were performed using visual and statistical inspections, and all spatial datasets were aggregated to the catchment scale using zonal statistics available in Google Earth Engine. For every index, monthly harmonization was achieved, and summary statistics were cross-validated against published regional norms13,60,61,62,63 to guard against bias.

Results and discussion

Sector-specific drought characteristics (1982–2023)

During the 1982–2023, the Jaraikela catchment experienced frequent but predominantly slight-to-moderate droughts across all four typologies. Meteorological droughts, as measured by SPAI-3, were most common in winter and pre-monsoon months, with slight [(SPAI-3)-1] and moderate [(SPAI-3)-2] events peaking due to low rainfall and high water demand. In contrast, severe [(SPAI-3)-3] and extreme meteorological droughts [(SPAI-3)-4] were rare and concentrated in the monsoon season13,61 (Figs. 4 and 5). Agricultural droughts, assessed via VHI, similarly showed a dominance of slight (VHI-1 and moderate events (VHI-2, particularly in the pre-monsoon months, reflecting persistent but manageable crop stress; severe agricultural droughts (VHI-3 were infrequent and absent during the monsoon, underscoring the buffering role of seasonal rainfall59,64 (see Figs. S2 and S3 in supplementary file). Hydrological droughts, indicated by SSI-3, displayed a high frequency of slight [(SSI-3)-1] and moderate events [(SSI-3)-2], especially in the dry season, with severe [(SSI-3)-3] events occurring mainly in the pre-monsoon months. These patterns indicate that while water scarcity is a recurring challenge, catastrophic hydrological failures remain rare, likely due to the catchment’s seasonal recharge and existing water management practices60,65,66 (see Figs. S4 and S5 in supplementary file). Environmental droughts, as captured by the EDI, revealed a distinct pattern: moderate (EDI-2) and severe (EDI-3) events were notably persistent, commonly lasting several months and peaking in the dry season, highlighting chronic stress on ecological flows and aquatic habitats (see Figs. S6 and S7 in the supplementary file). Extreme environmental droughts (EDI-4) were rare, but when they occurred, they posed significant threats to ecosystem stability. The seasonal alignment of environmental droughts with periods of increased water withdrawal emphasizes the vulnerability of riverine ecosystems to both climatic variability and anthropogenic demand31,67. In totality, across all types, drought duration analysis showed that slight (level-1) and moderate (level-2) droughts persist for extended periods, while severe (level-3) and extreme (level-4) drought events are brief but impactful.

(a) Comparative analysis of the values of the Standardized Precipitation Anomaly Index (SPAI) on the Y-axis (negative magnitude indicates water deficit while positive magnitude indicates water sufficiency and thus not shown) and with different SPAI-3 values [(SPAI-3)-1, (SPAI-3)-2, (SPAI-3)-3, and (SPAI-3)-4] on X-axis; (b) The number of meteorological drought events with different drought types for the observed period, i.e., 1982–2023 (For the findings on agricultural, hydrological, and environmental drought events, refer to the supplementary file’s Figs S1 to S6).

Drought-specific severity analysis by proportion (1982–2023)

The Jaraikela catchment’s drought regime (1982–2023) reveals stark contrasts in proportion of drought occurrences across meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental droughts (when each drought-type considered individually) (Fig. 6). Slight droughts dominate hydrological (58.8% of events), agricultural (62.1%), and meteorological (51.3%) categories, reflecting persistent but manageable water stress driven by seasonal demand fluctuations and precipitation variability68 (Fig. 6a). Hydrological droughts peak in pre-monsoon months, aligning with reduced streamflow and agricultural water withdrawals69. In contrast, environmental droughts exhibit distinct severity patterns: moderate (51% of events) and severe (36.7%) droughts prevail, disrupting instream flows critical for riparian habitats31,70. Only 8.8% of meteorological droughts reach severe status, underscoring rainfall deficits’ limited role in extreme droughts without compounding thermal or anthropogenic stressors55. Monthly analyses reveal divergent sectoral vulnerabilities (Fig. 6b). Hydrological droughts affect 63.7% of months, with slight deficits recurring annually during winter and pre-monsoon periods59. Environmental droughts, however, showed severe stress in 48.3% of months, concentrated in January–June when ecological flows fall below 40% of minimum requirements70. Agricultural droughts peak in March–May (57.1% slight, 40.5% moderate), coinciding with crop sowing and heightened evapotranspiration71. Notably, extreme droughts are rare (≤ 2.7% of months) and restricted to meteorological and environmental categories, mitigated by monsoon replenishment and groundwater buffering72,73. The findings from cross-drought frequency analysis for drought events and months highlight two key understandings: (1) Agricultural systems buffer moderate droughts via adaptive practices (e.g., drought-resistant crops), while environmental systems lack analogous safeguards, accelerating biodiversity loss during severe droughts31. (2) Pre-monsoon hydrological droughts (January–May) exacerbate ecological stress, yet monsoon-driven recharge (June–September) fails to offset cumulative deficits, creating a “water debt” that perpetuates drought cascades58.

Comparative analysis of the percentage (a) occurrence of an event of a drought of a particular type [for example, a slight meteorological drought occurred 41 times out of 80 events where 80 represents drought of all severity levels i.e., \(\{{\text{Slight}}_{event}/{(\text{Slight}+\text{Moderate}+\text{Severe}+\text{Extreme})}_{event}\}\times 100=(41/80)\times 100=51.3\text{\%}\)] and (b) the percentage of the total number of months witnessing an event of a drought of a particular type [for example, a slight meteorological drought occurred 62 times out of 112 months where 112 represents the number of months of all drought severity levels i.e., \(\{{\text{Slight}}_{month}/{(\text{Slight}+\text{Moderate}+\text{Severe}+\text{Extreme})}_{month}\}\times 100=(62/112)\times 100=55.4\text{\%}\)] for 1982–2023.

Combined drought severity analysis by frequency and persistence (1982–2023)

A comparative analysis of drought severity in the Jaraikela catchment over 1982–2023 reveals complex patterns in both the frequency and persistence of drought events and duration (when all drought events and their duration under meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental category are taken together and not individually) (Fig. 7). Slight and moderate droughts overwhelmingly dominate the region’s hydroclimatic regime, with 170 slight drought events spanning 323 months and 127 moderate events spanning 310 months. This persistent exposure to mild-to-moderate water deficits is characteristic of semi-arid landscapes, where recurring shortages continually stress soil moisture, crop productivity, and hydrological balance13,59,61,63,64,74,75. The near-equal duration of slight and moderate droughts suggests that moderate events commonly build upon pre-existing slight deficits, underscoring the cumulative nature of drought stress and the importance of adaptive strategies such as crop diversification and drought-resistant varieties72,73.

Comparative analysis of (a) the number of events of a drought of a particular severity (for example, a Slight Drought showing 140 events is due to the sum of 41 Meteorological Droughts, 54 Agricultural Droughts, 40 Hydrological Droughts, and 5 Environmental Droughts that caused Slight Drought) (b) the number of months witnessing an event of a drought of a particular severity (for example, a Slight Drought showing 200 months is due to the sum of 62, 72, 56 and 10 drought types, respectively, that caused Slight Drought), (c) the number of events of a drought of a particular type (for example, a Meteorological Drought showing 80 events is due to the sum of 41 Slight Droughts, 30 Moderate Droughts, 7 Severe Droughts, and 2 Extreme Droughts that caused Meteorological Drought) and (d) the number of months witnessing an event of a drought of a particular type (for example, a Meteorological Drought showing 112 months is due to the sum of 62, 40, 7, and 3 drought levels, respectively, that caused Meteorological Drought) for the study period 1982–2023.

Severe and extreme droughts, though infrequent (35 and 3 events, respectively), account for 147 and 6 drought months, with their impacts disproportionately high relative to their occurrence. Severe droughts are linked to prolonged dry spells, leading to substantial reductions in soil moisture, streamflow, and agricultural output, and necessitate robust resilience measures, especially for rainfed agriculture72,76. Extreme droughts, while rare and short-lived, can push regional water resources to critical thresholds, exacerbating impacts on crops, soils, and hydrological systems. This pattern highlights the need for both sustained conservation for frequent mild droughts and emergency responses for rare but intense events53,77,78.

Examining drought types, hydrological droughts are the most frequent (119 events, 281 months), reflecting the slow onset and prolonged recovery typical of surface and groundwater deficits in semi-arid basins79. Meteorological droughts (80 events, 112 months) are more transient, driven by erratic rainfall and monsoon variability51,61,80. Agricultural droughts (87 events, 126 months) commonly persist beyond meteorological deficits due to sustained soil moisture depletion from evapotranspiration, reducing crop yields and threatening food security49,50,52,64,81. Environmental droughts, though least frequent (49 events), are notable for their long persistence (267 months), reflecting the slow recovery of vegetation, biodiversity, and ecosystem services under extended dry conditions31,70.

Drought-specific epochal shift analysis (1982–2000 vs. 2001–2023)

A comparative individual drought epochal analysis reveals pronounced shifts in the frequency and severity of meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental droughts in the Jaraikela catchment between the late 20th (1982–2000) and early twenty-first centuries (2001–2023) (Fig. 8; see Fig. S8 in the supplementary file). Slight meteorological droughts (SPAI-3) became ubiquitous in the early twenty-first century, rising from 94.7 to 100%, while moderate events sharply increased from 57.9 to 87.0%. In contrast, severe meteorological droughts remained stable and extreme events disappeared, suggesting a transition toward more frequent but less intense rainfall deficits, likely driven by rising temperatures and evapotranspiration2,10,82. Similarly, slight agricultural droughts (VHI-1) increased marginally, but moderate events declined from 100 to 47.8%, and severe/extreme agricultural droughts vanished, reflecting the combined influence of accelerated soil moisture loss and improved adaptive practices58,72,76. In stark contrast, hydrological and environmental droughts intensified in both frequency and duration. Severe hydrological droughts (SSI-3) more than doubled, rising from 10.5 to 21.7%, while moderate events extended in duration, indicating persistent water scarcity linked to reduced monsoon intensity and hindered groundwater recharge61,73. Environmental droughts showed the most dramatic shift: severe events (EDI-3) surged from 31.6 to 52.2%, and extreme droughts (EDI-4) emerged at 4.3%. The decline in moderate environmental droughts alongside prolonged severe events signals escalating threats to biodiversity and ecosystem resilience31,70. These epochal trends underscore a growing “water debt” in the catchment, where monsoon recharge is increasingly insufficient to offset cumulative dry season deficits.

Combined drought epochal shift analysis (1982–2000 vs. 2001–2023)

A synthesis of drought event frequency and duration between the late 20th and early twenty-first centuries reveals a marked intensification and persistence of drought conditions (when all the drought events and types under meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental categories are taken together for consideration) (Fig. 9; see Figs. S9 and S10 in the supplementary file). The frequency of slight drought events increased substantially, indicating a shift toward more persistent, lower-intensity dry periods that cumulatively stress water resources and ecosystems. Moderate droughts remained relatively stable in frequency, while severe droughts rose sharply, reflecting the combined influence of rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and intensifying soil moisture deficits13,58,71,74. Extreme droughts, in contrast, became less frequent, suggesting a redistribution of drought severity toward more prolonged but less acute events. Hydrological and environmental droughts exhibited the most pronounced increases, with hydrological drought events and months both rising significantly, underscoring persistent water scarcity challenges driven by altered rainfall patterns and escalating demand31,58. Environmental droughts also intensified, as evidenced by a substantial increase in both the frequency and duration of severe and extreme events, highlighting growing ecosystem vulnerability under climate stress. Conversely, agricultural droughts declined in both event count and duration, likely reflecting the benefits of adaptive farming practices and improved management72,76. However, meteorological droughts increased in both frequency and duration, pointing to persistent climatic stressors affecting rainfall and water availability13,31,58,63,70. The duration analysis further reveals that slight drought months now dominate, exposing the region to chronic but manageable water stress, while severe drought months have also increased, amplifying the risk of acute resource shortages and ecosystem degradation52,64,81. Collectively, these epochal shifts underscore the necessity for regionally designed, multi-pronged adaptation strategies to improve resilience against intensifying drought risks in the Brahmani basin. Readers may kindly refer to media reports as discussed in supplementary information (Sect. S4.6, Table S1, and Table S2 in the supplementary file) regarding the further validation of the findings of this study with other studies and the strategic management framework that this study has designed and proposed for policymakers.

Comparative analysis of the occurrences of drought events between the Late 20th Century (1982–2000) and Early 21st Century (2001–2023) for different severity of the drought (a) and different types of the drought (b); Comparative analysis of the drought duration between the Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century for different severity of the drought (c) and different types of the drought (d).

Methodological distinctions, innovations, and pathways forward

Novelty and distinctions of comparative multi-index framework

This study advances the field of drought analysis by providing the first systematic, comparative multi-index assessment of meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental droughts in a climate-stressed, semi-arid Indian basin. The research distinctly employs a joint but independent analysis of the SPAI-3, VHI, SSI-3, and EDI across four decades for the Brahmani River basin’s Jaraikela catchment. The hallmark of this approach lies in the explicit, parallel evaluation of these four indices, avoiding integrative or composite methods that could obscure sector-specific vulnerabilities13,46. A central innovation of this work is its inclusion and systematic assessment of environmental drought, measured via the EDI, alongside established meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological indices31,70. This study thus provides an explicit environmental drought perspective embedded within the broader multi-index typology, viz., a perspective commonly omitted in previous regional assessments13,60,61,62,63.

The EDI was evaluated systematically and directly contrasted with the SPAI-3, VHI, and SSI-3, presenting a compelling and previously unavailable view of how climate-driven water deficits impact both managed (agricultural) and unmanaged (ecological) systems. The comparative approach reveals clear asymmetries in climate impacts: notably, environmental droughts not only emerge with greater persistence but also intensify more rapidly than their hydrological and agricultural counterparts across recent decades31,70. Such findings underscore that ecosystem-level vulnerabilities can outpace even those in food or water supply under escalating hydroclimatic extremes2,61. Additionally, the methodological structure established in this study yields a replicable and scalable template that can be readily adapted for drought risk assessment in other climate-vulnerable, data-limited regions, especially those seeking to harmonize agricultural productivity with ecosystem conservation. The study’s event-wise severity, frequency, and duration analysis further allows the detection of drought cascades and supports holistic risk management strategies46(also refer to Supplementary Section S1). This methodological decision of multi-index (single-factor) drought analysis is critical, as it allows for the unmasking of ecological drought acceleration, a phenomenon underdetected in previous studies using integrated frameworks13,31. The comparative approach delivers implementable, sector-specific understandings and demonstrates that, while adaptive agriculture may buffer moderate droughts, unmanaged ecosystems remain acutely vulnerable to chronic and severe water deficits. In doing so, the study addresses a substantial gap in current drought research and provides an urgently needed scientific basis for both adaptive water management and ecosystem resilience planning under climate change83.

Advantages and limitations: multi-index vs. compound (integrated) drought indices

A central methodological feature of this study is its explicit preference for a comparative, sector-resolved multi-index approach over compound (integrated) drought indices. By independently applying SPAI-3, VHI, SSI-3, and EDI, this framework preserves the unique responses and vulnerabilities of meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental systems, viz., dimensions that are commonly blended or masked in compound indices13,31.

Maintaining distinct, single-factor indices for each drought type allows for clear causal attribution of observed changes to specific drivers, whether climatic (e.g., rainfall deficit) or anthropogenic (e.g., altered water withdrawals). This level of granularity is particularly important when sector-specific signals must inform management, for instance, differentiating ecological versus agricultural adaptation needs in the Brahmani basin13,60,61,62,63. It also prevents the dilution of extremes: composite indices often obscure the episodic nature of severe droughts in one sector amid moderate conditions in another, potentially delaying targeted interventions. By tracking each drought type independently, as recommended by Zhang & Miao46 and practiced in contemporary studies, the multi-index strategy sharpens early warning and supports tailored policy responses. Real-time management becomes feasible, for example, by synchronizing reservoir releases or ecological flow supports to the sector most at risk31. However, the multi-index approach may under-represent the complexity and cascading nature of real-world droughts. Drought hazards can propagate from meteorological to hydrological and agricultural systems, sometimes with non-linearities and feedbacks that a single-index paradigm may not capture9,46,84,85. Moreover, concurrent moderate droughts across systems can create compound risks to food security and ecosystem health, synergies best detected through integrated indices84,85. Compound frameworks, such as the Integrated Drought Index13 or fuzzy logic approaches85, can synthesize multiple data streams, improve communication with non-expert stakeholders, and align with national policy or early-warning mandates84. These composite indices also facilitate macro-scale risk assessment, where multi-hazard mapping and resource allocation must be streamlined, which this study views it as a future scope.

Recent research affirms that compound and multi-variate indices commonly improve early warning accuracy84,85, yet for detailed basin-level management and sector-targeted adaptation, independently calculated multi-index approaches remain indispensable17,31,70. The present study demonstrates that while compound indices have clear communication and risk aggregation benefits, they may obscure new or rapidly intensifying hazards, such as environmental droughts, that only a sectoral comparison can reveal. Thus, selecting a multi-index versus integrated strategy must reflect the specific scientific and management objectives, the nature of regional vulnerabilities, and the sought balance between diagnostic detail and operational simplicity.

Future scopes and research pathways

Building on the foundation of sector-resolved multi-index analysis and recognizing the methodological and practical limitations identified in this study, several promising research avenues emerge for advancing drought science and policy utility. First, there is value in developing hybrid diagnostic frameworks that retain sectoral detail while facilitating dynamic integration. Drawing inspiration from high-dimensional integration methods, future work could facilitate simultaneous early warning for both single-system and compound-system drought threats. Such a hybrid approach would support both detailed scientific investigation and streamlined, implementable policy decisions, ensuring that critical sectoral signals are not obscured by aggregation while enabling rapid risk communication at larger scales. Second, refinement of the EDI provides fertile ground for innovation. While this study adopted a “maximum” logic (\(EDI = Max\{WSL, DDL\}\)) to conservatively guard against risk dilution, future developments should explore more sophisticated, potentially non-linear or synergistic forms. For example, statistical or ecological impact data could be integrated to define context-sensitive relationships between drought duration and intensity, allowing responsive calibration of EDI for diverse hydro-ecological contexts. Third, integration of Land Use/Cover Change (LUCC) and water withdrawal dynamics into drought modeling is essential, particularly in basins like the Brahmani, where rapid population growth and land transformation have altered hydrological regimes. Future studies should aim to explicitly incorporate high-resolution, temporally resolved LUCC and water abstraction data, especially for recent decades. This would allow more robust partitioning of climate-driven versus direct anthropogenic effects on drought patterns. Fourth, socioeconomic and governance dimensions warrant deeper integration. As drought impacts become increasingly multi-faceted under climate change, viz., affecting water security, food, and livelihoods as well as ecosystems, holistic frameworks that couple hydro-ecological indices with indicators of socioeconomic vulnerability and institutional resilience are called for. Such integration will be crucial for developing policy interventions and adaptive governance that are responsive to cross-sectoral drought risks. Finally, integrating advances in big data, earth observation, and artificial intelligence for near-real-time drought detection and forecasting could boost the practical relevance of multi-index approaches. Automated, high-frequency monitoring and predictive analytics could allow not only for proactive crisis management but also for the detection of subtle or emerging trends in drought propagation, improving resilience strategies. In sum, while this study sets a new benchmark for ecohydrological diagnosis and basin-scale drought management, future progress will hinge on moving toward smart integration, retaining the specificity of individual drought indices as a scientific foundation, but building adaptive, hybrid systems capable of navigating drought’s complexity and dynamism in an era of rapid environmental and societal change.

Conclusions

This study delivers the first systematic, comparative multi-index analysis of meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and environmental droughts, explicitly including the novel Environmental Drought Index (EDI), in a climate-stressed, semi-arid Indian basin. The research advances the field by distinctly employing a joint but independent analysis of SPAI-3, VHI, SSI-3, and EDI over four decades for the Brahmani River basin’s Jaraikela catchment, thereby preserving sectoral clarity and avoiding integrative or composite methods that could obscure specific vulnerabilities. This sector-resolved framework is a methodological innovation, with the systematic inclusion and assessment of environmental drought (via EDI) alongside established indices, yielding an explicit ecological perspective commonly omitted in previous regional work. By evaluating these indices in parallel, the study reveals that drought impacts are highly type- and severity-dependent, documenting clear asymmetries in climate impacts: environmental and hydrological droughts are shown to intensify and persist more rapidly in the early twenty-first century. Severe environmental droughts surged by 65% and hydrological droughts nearly doubled, while moderate agricultural droughts declined, highlighting divergent adaptation between managed and unmanaged systems. These findings demonstrate that conventional drought typology underestimates or misses ecological consequences, as environmental droughts accelerate faster than hydrological or agricultural droughts. The robust, comparative approach employed here yields a replicable and scalable template for drought risk assessment that can be adapted to other climate-vulnerable, data-limited regions, equipping stakeholders with implementable management strategies to harmonize agricultural productivity with ecosystem conservation. The inclusion of EDI specifically empowers detection of ecosystem-level stress and nurtures a holistic understanding of drought cascades and chronic vulnerabilities. Although adaptive farming and water management have buffered moderate agricultural droughts in recent decades, ecological systems remain highly vulnerable to persistent water shortages without analogous institutional safeguards.

Despite these advances, a few limitations warrant attention. The reliance on historical and remotely sensed data may mask local-scale variability, and the EDI, while novel, requires broader validation across diverse hydro-ecological settings. The current analysis does not integrate socioeconomic drought or explicitly quantify human adaptive responses, which are increasingly relevant under climate change. Additionally, the transferability of index thresholds and the effects of data resolution on drought detection merit further investigation. Drawing on these limitations, this study identifies several targeted avenues for future research. First, there is a need for hybrid diagnostic frameworks that facilitate dynamic integration of sectoral drought indices with EDI, supporting both detailed scientific analysis and rapid, effective risk communication. Second, refinement of the EDI, viz, potentially by exploring more sophisticated, non-linear, or context-sensitive relationships between drought duration (DDL) and water shortage intensity (WSL), will be essential for its broader applicability. Third, future assessments should explicitly incorporate high-resolution land use/cover change and water withdrawal data to partition climate-driven versus direct anthropogenic drought drivers, especially in rapidly developing basins. Holistic frameworks linking hydro-ecological indicators with socioeconomic vulnerability and governance capacity are also warranted. Finally, integrating advances in earth observation, big data, and artificial intelligence for near-real-time drought detection and impact forecasting could substantially enhance preparedness and response efficacy. Ultimately, this study provides a replicable template for drought assessment that can inform targeted management and conservation strategies, supporting resilience in vulnerable landscapes facing intensifying hydroclimatic extremes.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the TerraClimate repository (https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html), IDAHO_EPSCOR/TERRACLIMATE repository (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/IDAHO_EPSCOR_TERRACLIMATE), MODIS MOD11A2 dataset (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/MODIS_061_MOD11A2), NOAA CDR AVHRR NDVI V-5 dataset (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ncdc:C01558), MODIS MOD13A2 dataset (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/MODIS_061_MOD13A2), and India-WRIS repository (https://indiawris.gov.in/wris/#/RiverMonitoring). These datasets were accessed and processed using Google Earth Engine (GEE) and are publicly available for reproducibility and further research.

References

Biess, B., Gudmundsson, L., Windisch, M. G. & Seneviratne, S. I. Future changes in spatially compounding hot, wet or dry events and their implications for the world’s breadbasket regions. Environ. Res. Lett. 19(6), 064011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad4619 (2024).

IPCC (2023) Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1–34. https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001

Kuang, X., Liu, J., Scanlon, B. R., Jiao, J. J., Jasechko, S., Lancia, M., et al. (2024). The changing nature of groundwater in the global water cycle. Science. 383(6686), eadf0630. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf0630

Matanó, A., Hamed, R., Brunner, M. I., Barendrecht, M. H. & Van Loon, A. F. Drought decreases streamflow response to precipitation especially in arid regions. EGUsphere 2024, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-2715 (2024).

Srivastava, A., Maity, R., Desai, V.R. Assessing Global-Scale Synergy Between Adaptation, Mitigation, and Sustainable Development for Projected Climate Change. In: Chatterjee, U., Akanwa, A.O., Kumar, S., Singh, S.K., Dutta Roy, A. (eds) Ecological Footprints of Climate Change . Springer Climate. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15501-7_2 (2023).

Chandrasekara, S. S., Kwon, H. H., Vithanage, M., Obeysekera, J. & Kim, T. W. Drought in South Asia: A review of drought assessment and prediction in South Asian countries. Atmosphere 12(3), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12030369 (2021).

Berenguer, E. et al. Tracking the impacts of El Niño drought and fire in human-modified Amazonian forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118(30), e2019377118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019377118 (2021).

García-Redondo, C., Díaz-Raviña, M. & Regos, A. Long-term cumulative effects of wildfires on soil-vegetation dynamics in the “Baixa Limia-Serra do Xurés” Natural Park. Spanish J. Soil Sci. 14, 13103. https://doi.org/10.3389/sjss.2024.13103 (2024).

NIDIS. (2023). Drought assessment in a changing climate: Priority actions & research needs [Technical Report]. NOAA. https://www.drought.gov/documents/drought-assessment-changing-climate-priority-actions-and-research-needs (accessed July 19, 2025)

Zhao, M., Liu, Y. & Konings, A. G. Evapotranspiration frequently increases during droughts. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12(11), 1024–1030. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01505-3 (2022).

Spinoni, J., Vogt, J. V., Naumann, G., Barbosa, P. & Dosio, A. Will drought events become more frequent and severe in Europe?. Int. J. Climatol. 38(4), 1718–1736. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5291 (2018).

Srivastava, A., Maity, R., Desai, V.R. Assessing Global-Scale Synergy Between Adaptation, Mitigation, and Sustainable Development for Projected Climate Change. In: Chatterjee, U., Akanwa, A.O., Kumar, S., Singh, S.K., Dutta Roy, A. (eds) Ecological Footprints of Climate Change . Springer Climate. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15501-7_2 (2022).

Shah, D., & Mishra, V. (2020). Integrated Drought Index (IDI) for drought monitoring and assessment in India. Water Resources Res. 56(2), e2019WR026284. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026284

Palmer, W. C. (1965). Meteorological drought (Vol. 30). US Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau.

McKee, T. B., Doesken, N. J., & Kleist, J. (1993). The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology (Vol. 17, No. 22, pp. 179–183). https://climate.colostate.edu/pdfs/relationshipofdroughtfrequency.pdf

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S. & López-Moreno, J. I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 23(7), 1696–1718. https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JCLI2909.1 (2010).

Chanda, K. & Maity, R. Meteorological drought quantification with standardized precipitation anomaly index for the regions with strongly seasonal and periodic precipitation. J. Hydrol. Eng. 20(12), 06015007. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001236 (2015).

Palmer, W. C. Keeping track of crop moisture conditions, nationwide: The new crop moisture index. Weatherwise 21(4), 156–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00431672.1968.9932814 (1968).

Jackson, R. D., Idso, S. B., Reginato, R. J., & Pinter Jr, P. J. Canopy temperature as a crop water stress indicator. Water Resources r\Research, 17(4), 1133-1138. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR017i004p01133 (1981).

Sivakumar, M. V. K., Raymond P., Motha, R., Wilhite, D., & Wood, D. (2011). Agricultural Drought Indices. Proceedings of the WMO/UNISDR Expert Group Meeting on Agricultural Drought Indices, 2–4 June 2010, Murcia, Spain: Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization. AGM-11, WMO/TD No. 1572; WAOB-2011. 219 pp.

Kogan, F. N. Droughts of the late 1980s in the United States as derived from NOAA polar-orbiting satellite data. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 76(5), 655–668. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1995)076%3c0655:DOTLIT%3e2.0.CO;2 (1995).

Kogan, F. N. Application of vegetation index and brightness temperature for drought detection. Adv. Space Res. 15(11), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-1177(95)00079-T (1995).

Karl, T. R. (1986). The sensitivity of the Palmer Drought Severity Index and Palmer’s Z-index to their calibration coefficients including potential evapotranspiration. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26182460

Shafer, B. A., & Dezman, L. E. (1982). Development of surface water supply index (SWSI) to assess the severity of drought condition in snowpack runoff areas. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Western Snow Conference, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, 1982.

Shukla, S. & Wood, A. W. Use of a standardized runoff index for characterizing hydrologic drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL032487 (2008).

Mehran, A., Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. A hybrid framework for assessing socioeconomic drought: Linking climate variability, local resilience, and demand. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120(15), 7520–7533. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023147 (2015).

Guo, Y. et al. Assessing socioeconomic drought based on an improved Multivariate Standardized Reliability and Resilience Index. J. Hydrol. 568, 904–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.11.055 (2019).

Shi, H., Chen, J., Wang, K., & Niu, J. A new method and a new index for identifying socioeconomic drought events under climate change: A case study of the East River basin in China. Science of the Total Environment, 616, 363-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.321 (2018).

Liu, S., Shi, H., & Sivakumar, B. (2020). Socioeconomic drought under growing population and changing climate: A new index considering the resilience of a regional water resources system. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125(15), e2020JD033005. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD033005

Wang, T. et al. Socioeconomic drought analysis by standardized water supply and demand index under changing environment. J. Clean. Prod. 347, 131248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131248 (2022).

Srivastava, A. & Maity, R. Unveiling an Environmental Drought Index and its applicability in the perspective of drought recognition amidst climate change. J. Hydrol. 627, 130462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130462 (2023).

Leeper, R. D. et al. Characterizing US drought over the past 20 years using the US drought monitor. Int. J. Climatol. 42(12), 6616–6630. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.7653 (2022).

Ionita, M. & Nagavciuc, V. Changes in drought features at European level over the last 120 years. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussions 2021, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-1685-2021 (2021).

Jha, U., Dubey, S., Vaddadi, S. S., Upadhyaya, S., & Regonda, S. (2024). Integrated Monitoring and Analysis of Meteorological, Agricultural and Hydrological Droughts in the Ganga Basin in India. In 2024 IEEE India Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (InGARSS) (pp. 1–4). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/InGARSS61818.2024.10984247

Panday, D. P., Kumar, M., Agarwal, V., Torres-Martínez, J. A. & Mahlknecht, J. Corroboration of arsenic variation over the Indian Peninsula through standardized precipitation evapotranspiration indices and groundwater level fluctuations: Water quantity indicators for water quality prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 954, 176339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176339 (2024).

Sun, P. et al. Development of a nonstationary Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (NSPEI) and its application across China. Atmos. Res. 300, 107256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2024.107256 (2024).

Almouctar, M. A. S., Wu, Y., Zhao, F. & Qin, C. Drought analysis using normalized difference vegetation index and land surface temperature over Niamey region, the southwestern of the Niger between 2013 and 2019. J. Hydrol. Regional Stud. 52, 101689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101689 (2024).

Bourne, A. R. et al. Identifying areas of high drought risk in southwest Western Australia. Nat. Hazards 118(2), 1361–1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06065-z (2023).

Shahfahad, Talukdar, S., Ali, R., Nguyen, K. A., Naikoo, M. W., Liou, Y. A., et al. (2022). Monitoring drought pattern for pre-and post-monsoon seasons in a semi-arid region of western part of India. Environ. Monitoring Assessment. 194(6), 396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10028-5

Botai, C. M. et al. Hydrological drought assessment based on the standardized streamflow index: A case study of the three cape provinces of South Africa. Water 13(24), 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13243498 (2021).

Klaho, M. H., Alijanian, M. & Moeini, R. A new promoted Surface Water Supply Index for multi-faceted drought assessment. Stochastic Environ. Res. Risk Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-025-02935-z (2025).

Lema, F. et al. What does the Standardized Streamflow Index actually reflect? Insights and implications for hydrological drought analysis. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 29(8), 1981–2002. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-1981-2025 (2025).

Srivastava, A., Maity, R., & Desai, V. R. Synthesising causal loop between environmental and compound droughts: A systems-driven framework for climate-resilient governance in monsoon-sensitive agroecosystems. Next Sustainability, 6, 100159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxsust.2025.100159 (2025).

Cao, S. et al. Effects and contributions of meteorological drought on agricultural drought under different climatic zones and vegetation types in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153270 (2022).

Sharma, A., Sharma, D. & Panda, S. K. Assessment of spatiotemporal trend of precipitation indices and meteorological drought characteristics in the Mahi River basin, India. J. Hydrol. 605, 127314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127314 (2022).

Zhang, L. & Miao, C. A high-resolution multi-drought-index dataset for mainland China (1961–2022). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 17(1), 837–852. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14634773 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Anthropogenic drought in the Yellow River basin: Multifaceted and weakening connections between meteorological and hydrological droughts. J. Hydrol. 619, 129273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129273 (2023).

Zhou, Z., Shi, H., Fu, Q., Ding, Y., Li, T., Wang, Y., & Liu, S. (2021). Characteristics of propagation from meteorological drought to hydrological drought in the Pearl River Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126(4), e2020JD033959. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD033959

Bharambe, K. P., Shimizu, Y., Kantoush, S. A., Sumi, T. & Saber, M. Impacts of climate change on drought and its consequences on the agricultural crop under worst-case scenario over the Godavari River Basin, India. Clim. Services 32, 100415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2023.100415 (2023).

Pachore, A. B., Remesan, R. & Kumar, R. Multifractal characterization of meteorological to agricultural drought propagation over India. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 18889. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68534-0 (2024).

Chatterjee, S., Desai, A. R., Zhu, J., Townsend, P. A. & Huang, J. Soil moisture as an essential component for delineating and forecasting agricultural rather than meteorological drought. Remote Sens. Environ. 269, 112833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112833 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, W., Singh, V. P. & Ren, L. A global perspective on the probability of propagation of drought: From meteorological to soil moisture. J. Hydrol. 603, 126907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126907 (2021).

Müller, L. M. & Bahn, M. Drought legacies and ecosystem responses to subsequent drought. Glob. Change Biol. 28(17), 5086–5103. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16270 (2022).

Tennant, D. L. Instream flow regimens for fish, wildlife, recreation and related environmental resources. Fisheries 1(4), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446(1976)001%3c0006:IFRFFW%3e2.0.CO;2 (1976).