Abstract

The increasing global population and rapid technological advancements are driving a surge in energy demand. Meanwhile, fossil fuel dependence as a primary energy source is contributing to environmental issues, including greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. These challenges underscore the urgent necessity of transitioning to sustainable energy solutions. Renewable energy systems (RES) are critical alternatives that can facilitate sustainable development goals. Nevertheless, the selection of the most suitable RES for specific geography, particularly within Industry 4.0, poses substantial decision-making complexities due to the intricate criteria involved. This paper introduces a robust method for evaluating RES. The proposed approach integrates f, g, h-fractional fuzzy sets (f, g, h-FrFS) into multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM), enhancing the decision-making process. The f, g, h-FrFS framework effectively captures decision-makers’ preferences by considering membership degrees (MB), non-membership degrees (NMB), and indeterminacy degrees (ID). Initially, the importance of evaluation criteria is determined through the improved Criteria Importance through Inter-Criteria Correlation (CRITIC) method. Following this, the WASPAS model is used to provide an accurate ranking of the RES. Geothermal energy is recognized as the most reliable RES option. To test the robustness of the proposed approach, a sensitivity analysis is conducted, demonstrating the stability of the model under varying conditions. The effectiveness of this framework is further validated through a comparative study analysis. Ultimately, this technique offers significant value for policymakers, energy managers, and organizations involved in renewable energy systems. In Industry 4.0, energy planning and development is complicated, so this tool can assist them in navigating the complexities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy is a fundamental element of human existence and a key driver of national economic development. The global population is growing exponentially, and energy production is considered a major challenge due to industrial development. A growing population along with technological advancements, increase energy demand. Energy can be sourced from fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and oil. In addition, it can be sourced from renewable resources, such as wind, solar, hydro, and thermal energy. However, fossil fuels have significantly contributed to greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating global warming and climate change1,2. As a result of climate uncertainty, we have seen a variety of extreme weather events around the world in recent years, including flooding, storms, and droughts. Environmental damage is caused by elevated carbon emissions from fossil fuels for energy production3. The intensification of climate uncertainty makes traditional energy sources unreliable.

Sustainability and the transition toward resilient societies are currently leading the international agenda4. Integrated social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainable development are at the heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. To achieve sustainable energy growth, emissions must be reduced, renewable energy sources must be replaced with fossil fuels, and energy efficiency must be improved5. The use of renewable energy resources such as wind, geothermal power, solar, biomass, and hydroelectricity can also be considered a viable substitute for fossil fuels6,7. Renewable energy technologies are rapidly evolving worldwide, and several forecasts expect that their development will have a substantial influence in the near future8. The reason for this is that these energy sources are more cost-effective than traditional energy sources when it comes to electricity generation. However, determining the right renewable resource for a given location and requirement can be difficult, since each source may offer a unique set of advantages. It is imperative to employ multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques in real-life scenarios since they are generally challenging.

In practical scenarios, acquiring accurate data is often challenging due to factors such as incomplete or contradictory information, privacy limitations, and the complexities of combining data from various datasets. Nevertheless, these challenges can be addressed by utilizing numerous fuzzy number extensions. Spherical fuzzy sets (SFS) face limitation to the square sum of negative (NMB), positive (MB), neutral (ID) and degree is limited to 19. In this way, fuzzy information is restricted from being included. To compensate for this limitation, t-spherical fuzzy sets (t-SFS) are used, in which the sum of the t-th powers of neutral, positive, and negative degree values cannot exceed 110. In cases where full satisfaction is held by a decision-maker about a possible course of action, a value of 1 may be assigned as an evaluation score for that possible option. Gulistan et al. introduced f, g, h-fractional fuzzy numbers (f, g, h-FrFNs) and utilized aggregation operators to select a stable currency in the crypto market11. In this context, MB indicates the extent to which a particular alternative completely meets a specific criterion, NMB denotes the degree to which a particular alternative is deemed not to fulfill a criterion, and ID captures the level of ambiguity or unclarity concerning the degree of satisfaction of an alternative. Traditional CRITIC and WASPAS models are limited in their ability to compute the maximum value (equal to 1). The application of f, g, h-FrFNs has not been extended in MCDM techniques. This study bridges the identified research gap by extending the CRITIC and WASPAS models for f, g, h-FrFNs. This study introduces the CRITIC model to compute criteria weights and WASPAS model to rank alternatives using f, g, h-FrFNs in the MCDM dilemma.

Research gaps and motivations

To address ambiguities in decision-making, the existing fuzzy sets and their various modifications, such as SFS9 and t-SFS10 have been utilized. However, these methods often fail to fully capture the MB and NMB, which limits the accuracy and reliability of the decision-making process. For instance, consider a set with the description \(D = (d, \langle 1.0, 0.75, 0.45\rangle , d \in D)\), which demonstrates that these methods are inadequate for handling such information. This limitation arises because datasets can only be accommodated by SFSs if the square sum of ID \((\mathfrak {z})\), MB \((\mathfrak {p})\), and NMB \((\mathfrak {j})\) is less than or equal to 1 \((\mathfrak {p}^2 + \mathfrak {z}^2 + \mathfrak {j}^2 \le 1)\). Furthermore, t-SFSs can only take into account datasets if the sum of the t-th powers of \(\mathfrak {z}\), \(\mathfrak {p}\), and \(\mathfrak {j}\) is less than or equal to 1 \((\mathfrak {z}^t + \mathfrak {p}^t+ \mathfrak {j}^t \le 1)\). Since there are shortcomings to conventional fuzzy set frameworks, such as SFS and t-SFS, Gulistan et al. introduced the p, q, r-fractional fuzzy set methodology11. In addition to providing enhanced flexibility and versatility, this structure allows for the representation and manipulation of information that is not adequately accommodated by traditional fuzzy sets.

The RES case study investigated by Toqee et al.59 considers only the MB and NMB degrees and fails to address the maximum MB value. It fails to account indeterminacy degree in decision making process, which is crucial for modeling the inherent uncertainty in decision-making processes. Additionally, when a decision-maker is fully confident to evaluate one alternative with respect to specific criteria he will assign membership degree 1 for that alternative, and model presented by Toqeet et al. is unable to handle this situation. So we need to develop a model that will incorporate indeterminacy degree and also able to handle maximum membership value 1. Our study resolves this limitation by incorporating the indeterminacy degree and achieving a maximum membership value 1 through the use of fractional fuzzy numbers. By doing so, our model offers a more comprehensive and accurate framework for sustainable energy planning, enabling better decision-making under uncertainty.

WASPAS and CRITIC models developed on existing fuzzy sets are unable to handle expert judgments at their maximum value point22,27. Therefore, we need to introduce a robust CRITIC method to determine criterion weights and the WASPAS method to rank alternatives and handle expert maximum judgments in decision-making. This model aims to offer a more robust, flexible, and accurate solution to assessing RES within the scope of Industry 4.0, eliminating existing gaps and making it a valuable addition to sustainable energy decision-making. The study highlights that current methods for assessing sustainable RES are insufficient. Despite considerable research into various assessment methods, there is a clear lack of integration of advanced fuzzy set principles, particularly fractional fuzzy sets. Fractional fuzzy sets could help address inherent uncertainty and ambiguity in sustainability evaluations. To enhance the accuracy and depth of sustainability assessments, this study proposes a hybrid approach combining CRITIC and WASPAS methods. This innovative methodology fills a significant gap in the literature by offering a more robust methodology to assess RES long-term viability. It can contribute to green energy technologies and sustainable development initiatives. This study is motivated by the pressing demand for more reliable and efficient methodologies in decision-making when evaluating RES within the realm of Industry 4.0.

Contributions

Real-world challenges are attracting the attention and time of more and more DMs, and they are developing realistic responses to them. When situations become more complex, it becomes progressively trickier for DMs in the adaptive decision-making paradigm to determine the best response. The real-life problems encountered by DMs require practical and sustainable solutions. To evaluate RES in a sustainable way, this study is imperative, which eliminates many challenges. Significant contributions of this research fills the aforementioned gaps in the literature:

-

To optimize RES, an MCDM problem is presented and solved in a f, g, h-FrFNs environment.

-

An MCDM numerical application for the determination of sustainable RES in industry 4.0 is used to demonstrate the validity of the developed methodreal.

-

CRITIC method is extended in this paper to incorporate f, g, h-FrFNs into criteria weight calculations for MCDM scenarios.

-

To improve the MCDM in f, g, h-FrFNs, we have developed a more advanced f, g, h-FrFN based WASPAS technique.

The main objective of this study is to evaluate renewable energy systems (RES) for sustainable development in industry. Employing innovative models such as CRITIC to compute criteria weights and WASPAS for RES selection, it provides a robust MCDM model within f, g, h-FrFNs context. The integration of both models improves the robustness of decision-making. A critically important contribution to the research on RES is this scholarly work, which highlights the powerful capability for innovative decision-making frameworks to overcome industry challenges that are complex and multifaceted. To summarize, the purpose of this study is to develop data-driven technique to help businesses, policymakers, and individuals in identifying RES that are most efficient for their industry. As an overview of the study, an introduction is provided in Sect. 1, followed by a detailed literature review in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, preliminary definitions are discussed. The proposed work is described in Sect. 4. RE systems are defined in Sect. 5. A real-life decision-making problem is examined in Sect. 6. Section 7 presents performance evaluation metrics. An overview of the detailed discussion is presented in Sect. 8. This study is concluded with some limiting factors and future potentials in section 9.

Literature review

Effectively addressing contemporary challenges requires informed decisions. The issue of data uncertainty poses significant challenges across scientific domains, including engineering, industrial production, agriculture, and economics. This dilemma has been addressed by several researchers13,14,15. Modeling ambiguous data is not possible using traditional mathematical frameworks. Zadeh developed the fuzzy set concept (FS) in 1965 to represent ambiguous, vague, and uncertain elements16. FS is not capable of handling non-membership degrees (NMB). Among the limitations of fuzzy sets, Atanassov proposed an intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS) in 198617. In MCDM, IFS is widely acknowledged as one of the best tools for describing and managing ambiguity. However, this modification is generally limited because it does not address indeterminacy degrees (ID). Therefore, Gundogdu9 came up with the concept of a SFS. The decision expert in SFS has more flexibility when making decisions compared to IFS. Based on the approach discussed by Mahmood et al.10, t−SFS are more generalized types of fuzzy system. Garg18 investigates the connection between t−SFS, and the operators that aggregate them, as well as developing the operational laws of t−SFS.

The previous analysis indicates that all the researches investigated apply varying powers to control membership tiers. As an example, for membership in SF structures, decision-makers employ a power of two, while for membership in t-SF structures, they employ a power of t. Decision-makers utilize unique powers to manage the influence of membership levels in alignment with approaches designed to address different levels of uncertainty and ambiguity. Although, in particular real-life situations, if the decision-maker is satisfied about a certain alternative, he or she may give it a score of 1 when rating the strategy. If a set representation is defined as \(D = (d, 1, 0.45, 0.65)\) where \(d \in D\), existing models may not facilitate such evaluation. As a future advancement of existing studies, Gulistan et al. proposed a p, q, r-fractional fuzzy sets in 202411. In addition to offering improved functionality and versatility, this novel structure allows information to be visualized and handled that is not sufficiently supported by conventional fuzzy sets.

Literature review of the evolution of CRITIC and WASPAS models

This literature review investigates key developments in decision-making approaches, emphasizing the integration of MCDM techniques with methodologies based on CRITIC and WASPAS. To obtain an accurate and robust ranking of different options, weights are essential in MCDM. Every MCDM problem has distinct values for the criteria. Consequently, weights are calculated to quantify how important each criterion and how much it weighs. The intercriteria correlation technique (CRITIC), proposed by Diakoulaki et al. (1995)19, is one of several methodologies available for calculating objective and subjective weights in MCDM processes. This approach determines weights by leveraging criteria correlation coefficients.

Serken et al.37 employed an integrated CRITIC WASPAS fuzzy model to analyze the performance indicators of the digital transformation process in renewable energy projects. Rostamzadeh et al.38 used an integrated fuzzy TOPSIS CRITIC approach for sustainable supply chain risk management. Pathak et al.39 evaluated the major elements affecting the adoption of blockchain technology. A fuzzy modification of the CRITIC and SWARA methods for quantifying objective and subjective weights of criteria was presented by Ghorabaee et al.40. Ke et al.41 introduced an innovative integrated weighting algorithm that incorporates the CRITIC and BMW models, utilizing an IFS for the selection of urban comprehensive energy infrastructure plans. Tronnebati et al.42 conducted an analysis and ranking of the obstacles to the adoption of food supply chains that are more resilient. Multiple criteria complex decision-making problems can be tackled using the CRITIC model, a robust MCDM approach. Table 1 presents research studies developed using the CRITIC algorithm.

The Sum additive weighting model (SAW) and weighted product model (WPM) are combined to develop the Weighted aggregated sum product assessment (WASPAS) method, which gives an accurate solution to MCDM problems. The utility degree is calculated by WASPAS to rank alternatives based on their importance. Zavadskas et al.43 introduced the WASPAS model for optimization of weighted aggregated function. Tronnebati et al.42 evaluated the e-trade platforms within the automotive spare parts industry, examining various critical aspects to identify the optimal platforms. Serken et al.37 employed an integrated CRITIC WASPAS fuzzy model to analyze the performance indicators of the digital transformation process in renewable energy projects. Rudnik et al.44 proposed an approach for the selection of improved projects. Singh45 employed and integrated WASPAS model to optimized the performance of solar water heating system. Table 2 explores the research developed based on the WASPAS method.

Literature review on sustainable RES

Renewable energy sources integration into both national and global energy systems involves several challenges, such as variability in resources, technological practicality, economic feasibility, and environmental consequences46,47. MCDM approaches address these issues by:

-

Methodically assess various possible conflict factors.

-

Improving decision-making efficiency for policymakers, financiers, and other key stakeholders.

-

Offering flexible frameworks that can be adapted to numerous energy models and regional settings.

-

Enabling a systematic evaluation of various renewable energy options, including solar, biomass, hydro, and wind. By evaluating a range of criteria at once, MCDM supports decision-makers in formulating more comprehensive, efficient energy policies that promote resiliency and sustainability.

The current review examines significant research that has enhanced our understanding of renewable energy technologies sustainability. It highlights key studies that contribute to improving our ability to assess and manage RES with sustainability as a core consideration. However, relatively few studies focus on renewable energy sources, sustainable development, and adoption. Mohammad Reza et al.48 studied the importance of renewable energy resources for Iran’s electricity sector, utilizing the Simultaneous Evaluation of Criteria and Alternatives method to assess seven alternatives based upon twelve criteria. Abdel-Basset et al.49 introduced a hybrid MCDM approach using neutrosophic sets to determine the most appropriate sustainable renewable energy system. They evaluated four renewable energy sources based on five primary criteria and eighteen sub-criteria. Torul Yürek et al.50 applied MCDM using Pythagorean fuzzy sets to assess hybrid renewable energy sources through a sustainability index and rank renewable energy technologies in Turkey. Büyükozkan et al.51 proposed an integrated model for selecting renewable energy in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals of United Nations, using a hesitant fuzzy linguistic set. They evaluated four alternatives based on four primary criteria and twenty sub-criteria. Further studies are outlined in Table 3.

Preliminaries

Some basic concepts of f, g, h-fractional fuzzy sets11 are described in this section. Providing critical support and utility for the integrated model introduced, these fundamental concepts are crucial resources. Fractional fuzzy sets provide a generalized form of IFS, PFS, SFS, and t-SFS.

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy set

For a fixed collection of elements in a set \( \mathscr{R}\), a f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy set (f, g, h-FrFS) \({\widetilde{S}}\) on a component \(\mathfrak {r} \in \mathscr{R}\) is represented as11:

In this context, \({\mathfrak {p}}_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {r}) \in [0, 1]\) indicates belonging degree, \({\mathfrak {z}}_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {r}) \in [0, 1]\) indicates impartial belonging degree, while \({\mathfrak {j}}_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {r}) \in [0, 1]\) indicates non-belonging degree of an element \(\mathfrak {r} \in \mathscr{R}\) fulfilling the condition \(\frac{1}{f}({\mathfrak {p}}_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {r})) + \frac{1}{h}({\mathfrak {z}}_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {r})) + \frac{1}{g}({\mathfrak {j}}_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {r})) \le 1\), here g and f are positive integers with condition \(f, g \ge 1\), and \(h = {LCM}(g, f)\).

The triplet \(({\mathfrak {p}}, {\mathfrak {z}}, {\mathfrak {j}})\) satisfying the condition \(\frac{1}{f}({\mathfrak {p}}) + \frac{1}{h}({\mathfrak {z}}) + \frac{1}{g}({\mathfrak {j}}) \le 1\) is called f, g, h-FrFN, where \(g, f \ge 2\) and \(h = {LCM}(g, f)\).

Each time f, g, h-FrFNs \({\widetilde{S}}\), the score function associated with \({\widetilde{S}}\) can be formulated as:

Accordingly, f, g, h-FrFN has the following accuracy function \(\widetilde{S}\):

As a basic definition of arithmetic operations, let us consider the following: \(\tilde{O} = ({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{O}}, {\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{O}}, {\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{O}})\) and \(\tilde{V} = ({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{V}}, {\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{V}}, {\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{V}})\) then:

-

Addition Operation

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} \tilde{O} \oplus \tilde{V} = \left( \frac{1}{f}{\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{O}} + \frac{1}{f}{\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{V}} - \frac{1}{f}({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{O}})({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{h}({\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{O}})({\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{g}({\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{O}})({\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{V}}) \right) \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(4) -

Multiplication Operation

$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{O} \otimes \tilde{V} = \left( \frac{1}{f}({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{O}})({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{h}{\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{O}} + \frac{1}{h}{\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{V}} - \frac{1}{h}({\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{O}})({\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{g}{\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{O}} + \frac{1}{g}{\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{V}} - \frac{1}{g}({\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{O}})({\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{V}}) \right) \end{aligned}$$(5) -

A scalar number \(\lambda > 0\) multiplication

$$\begin{aligned} \lambda \cdot \tilde{O} = \left( \frac{1}{f}({\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{O}})^\lambda , \frac{1}{h}({\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{O}})^\lambda , 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{g}{\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{O}}\right) ^\lambda \right) \end{aligned}$$(6) -

Scalar power \(\lambda > 0\)

$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{O}^\lambda = \left( 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{f}{\mathfrak {p}}_{\tilde{O}}\right) ^\lambda , 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{h}{\mathfrak {z}}_{\tilde{O}}\right) ^\lambda , \frac{1}{g}({\mathfrak {j}}_{\tilde{O}})^\lambda \right) \end{aligned}$$(7)

f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted averaging operator

Suppose \(\{\widetilde{R}_1, \widetilde{R}_2, \ldots , \widetilde{R}_n\}\) represents a collection of f, g, h-FrFN. Assume \({\xi _y} = (\xi _1, \xi _2, \ldots , \xi _n)\) denote the corresponding weight vector for the f, g, h-FrFNs, where each weight satisfies \({\xi _y} \in [0, 1]\), and \(\sum {\xi _y} = 1\) for all \(y = 1, 2, \ldots , n\). In terms of f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted averaging (f, g, h-FrFWA) operator12 is \({f, g, h}-{FrFWA}: \triangle ^n \rightarrow \triangle\) and the function is written as follows:

f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted geometric operator

Suppose \(\{\widetilde{R}_1, \widetilde{R}_2, \ldots , \widetilde{R}_n\}\) represents a collection of f, g, h-FrFN. Assume \({\xi _y} = (\xi _1, \xi _2, \ldots , \xi _n)\) denote the corresponding weight vector for the f, g, h-FrFNs, where each weight satisfies \({\xi _y} \in [0, 1]\), and \(\sum {\xi _y} = 1\) for all \(y = 1, 2, \ldots , n\). In terms of f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted geometric (f, g, h-FrFWG) operator12 is \({f, g, h}-{FrFWG}: \triangle ^n \rightarrow \triangle\) and the function is written as follows:

Proposed work

This section presents two key contributions to fuzzy MCDM:

-

A novel CRITIC method for criteria weight determination within f, g, h-fractional fuzzy settings.

-

A robust WASPAS approach to alternative evaluation.

Our primary objective is to develop a combined f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS framework that:

-

Using dynamic computing, calculated criterion significance through the CRITIC method.

-

Incorporates dual aggregation within WASPAS for robust alternative assessment.

-

Enhances evaluation accuracy in complex decision environments.

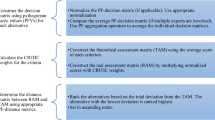

Figure 1 demonstrates the comprehensive workflow of our developed methodology, which combines the strengths of both approaches.

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy CRITIC

In this study, we develop the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC methodology to assess criteria weights for sustainable renewable energy system selection. This approach integrates real-time situational factors, expert judgment, and fractional fuzzy uncertainty handling, making it highly effective for dynamic criteria prioritization, managing ambiguous expert assessments, and maintaining mathematical precision in complex evaluations. The procedural steps of the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC methodology are outlined as below:

Step 1: Experts are evaluated and their authority is evaluated. According to Table 4, experts are classified according to their qualifications and experience. Expert weights are calculated according to the formula found in Eq. 10. With \(E_y = (\mathfrak {p}_y, \mathfrak {z}_y, \mathfrak {j}_y)\) representing the associated FrFN, expert weights are computed based on their experience and knowledge.

Step 2: To evaluate alternatives, decision makers provide assessments based on the significance of predefined criteria. These evaluations are expressed using linguistic variables, which are then converted into FrFNs for quantitative analysis. The corresponding linguistic scale for FrFN conversion is provided in Table 5. The assessments from multiple experts are systematically organized into y decision matrices, structured as (Eq. 11) and it facilitates structured analysis and comparison of alternatives.

In each matrix, the evaluation outcome is depicted, where \(\mathfrak {Z}^{(y)}_{kl}\) denotes the evaluation result presented by the \(y\)-th decision expert (\(y = 1, 2, \dots , s\)) for the \(k\)-th alternative (\(k = 1, 2, \dots , m\)) concerning to the \(l\)-th factor (\(l = 1, 2, \dots , n\)) within the f, g, h-FrF methodological approach.

Step 3: A combined f, g, h-FrF decision matrix is formed by combining independent expert evaluations. Experts with a greater weight exert a stronger influence on the aggregated outcome. The evaluation of each criteria incorporates all experts’ inputs using Eq. 12, with the resulting matrix structured as Eq. 13.

The aggregated value of criterion l is \(z_l\).

Step 4: The decision score matrix can be calculated according to Eq. 14.

Step 5: In many attribute sets, there are two groups, called benefit element and cost element, which are referred to as BE and CE, accordingly. The decision attributes are not required to be normalized if they are all BE or CE. When there are BE and CE evaluations in MCDM, CE ratings are converted to BE ratings. To transform the data into a f, g, h-FrF decision matrix, use Eq. 15.

where \(\mathfrak {Z}_{l}^{-} = \min \mathfrak {Z}_{kl}\) and \(\mathfrak {Z}_{l}^{+} = \max \mathfrak {Z}_{kl}\).

Step 6: Determine the correlation coefficient by applying Eq. 16, which reflects the extent of association between the two criteria. A value of “1” indicates a perfect positive relationship, whereas “-1” represents a perfect negative relationship. Calculation of correlation coefficients among all criteria is as below:

where \(\overline{\mathfrak {N}_l} = \frac{\sum _{k=1}^{m}\mathfrak {N}_{kl}}{m}\) and \(\overline{\mathfrak {N}_o} = \frac{\sum _{k=1}^{m}\mathfrak {N}_{ko}}{m}\)

Step 7: Standard deviation can be determine using Eq. 17.

Step 8: Compute the information index using Eq. 18.

Step 9: Determine the weights by employing Eq. 19

f, g, h-fractional fuzzy WASPAS

An enhanced version of the WASPAS method incorporating f, g, h-FrFS is introduced below:

Step 10: Collect insights from a panel of individuals responsible for making decisions regarding the potential for sustainable renewable energy systems. This depends on how significant the criteria are. Information collected with the help of Table 5 and the evaluation results provided by the decision-makers can be orderedly organized into y decision matrices as Eq. 20:

A matrix grid like the one above represents a set of evaluation results, where \(\mathfrak {Z}^{(y)}_{gl}\) denotes the evaluation outcome assigned by the \(y\)-th decision expert (\(y = 1, 2, \dots , s\)) for the \(g\)-th alternative (\(g = 1, 2, \dots , m\)) concerning to the \(l\)-th criteria (\(l = 1, 2, \dots , n\)) within the f, g, h-FrF settings.

Step 11: A combined decision matrix for f, g, h-FrF is constructed by combining independent expert evaluations. Assessment of each criteria by consolidating the evaluations of all experts through Eq. 21, with the resulting combined matrix expressed as Eq. 22.

A criterion’s cumulative result is expressed by \(z_l\) for the criteria l.

Step 12: The SAW algorithm is employed to \( \mathscr{E}^{agg}\) by integrating the criterion weights to compute the \(\widehat{SAW}\) f, g, h-FrF scores of all systems using Eq. 23.

Step 13: The weighted measurements for each characteristic are aggregated through an addition operation as specified in Eq. 24.

Step 14: The WPM algorithm is implemented to \( \mathscr{E}^{agg}\) by integrating the criterion weights to compute the \(\widehat{WPM}\) f, g, h-FrF scores for all systems, as shown in Eq. 25.

Step 15: The product algorithm is applied to compute the product of the respective assessments for each factor, as represented by Eq. 26.

Step 16: The threshold number \(\Gamma\) is applied to the f, g, h-fractional fuzzy values of WPM and SAW in order to incorporate their fractional fuzzy values. As a result of applying Eq. 27, we are able to determine the result of each alternative.

Step 17: The optimal option should be determined by sorting the options in descending sequence.

Renewable energy systems optimization: a case study

According to the developed model, the objective of the present section is to identify the most suitable renewable energy system based on the utilization of the presented framework. A sustainable ecosystem can be achieved by optimizing the efficiency of RESs. A problem analysis is developed, followed by a discussion of criteria and solutions and a graphical illustration is outlined in Fig. 2. The developed algorithm is then adopted in order to determine an approach to the problem. The final step involves conducting a sensitivity analysis and performing comparative evaluations.

Problem background for RES

Rapid growth in technology, industrialization, and the population across the globe is driving a significant increase in energy consumption. Therefore, the issue has become increasingly critical. Current non-renewable energy sources, which rely on technologies that contribute heavily to carbon emissions, are not able to meet this escalating demand sustainably. In line with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs), more and more countries are shifting towards renewable energy solutions. Many countries are pursuing renewable energy solutions to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). To reach its sustainability targets, Turkey is actively exploring renewable energy sources that are cost-effective, efficient, socially beneficial, and ecologically sustainable. Turkey has significant potential for renewable energy. When evaluating renewable energy sources, several factors need to be considered, including their effectiveness, economic value, carbon footprint, investment costs, environmental impact, and social legitimacy60,62,63,64. It is essential that renewable energy solutions have a minimal negative influence on the economy and the community, while maximizing their technological and social benefits. Given the complexity of these factors, some of which may be conflicting, MCDM methods have become crucial in evaluating renewable energy options that align with sustainable development. To address these challenges, a hybrid model, combining fractional fuzzy numbers with CRITIC and WASPAS methods, has been developed. This model accounts for the inherent uncertainty and imprecision involved in renewable energy evaluation, ensuring sustainable development principles are integrated into the decision-making process. The model simplifies the complex task of renewable energy selection by considering the contributions of multiple decision-makers with expertise in sustainable development and renewable energy.

A comprehensive catalog of potential sources of renewable energy for Turkey is being prepared by three managers from different departments. They conducted thorough research and professional discussions to arrive at the following options: wind60, solar61, biomass62, geothermal energy63, and hydropower65. Although this list is not exhaustive, it serves as a starting point for evaluating available options. To facilitate a well-rounded analysis, a wide range of criteria are employed, encompassing environmental, social, political, economic, and technical considerations. Figure 1 presents an MCDM framework designed to optimize renewable energy sources selection. This framework supports the evaluation and decision-making methodology in determining the most appropriate energy sources, while Fig. 2 showcases the proposed model for optimizing renewable energy systems (RES).

Description of renewable energy systems

The modern era has made energy an essential component of nation development and sustainable growth. The world’s major energy sources are fossil fuels, oil, and gas which are reliable but unsustainable. A significant amount of carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning may cause significant environmental damage. The Sustainable Development Goals have been detailed by the United Nations. Renewable energy is becoming increasingly important for achieving these goals. The following case study is taken from research conducted by Jameel et al.59. This project was carried out in Turkey, demonstrating how renewable energy systems are selected in the country. Turkey is seeking socially appropriate, technologically efficient, economical, and climatically acceptable renewable energy systems to achieve its sustainable development goals. Sustainable RESs require careful evaluation of potential sources, including wind, biomass, solar, geothermal energy, and hydraulics. These alternatives are briefly discussed below.

Wind energy (\(\mathfrak {F}_1\))

With the use of wind turbines, we can capture the kinetic power of circulating air and turn it into electricity that is useful for everyday use. Wind energy is recognized for its eco-friendly advantages. It is true that the upfront financial commitment to wind farms may be higher than in alternative sources of electricity; however, they provide significant financial benefits to both developed economies as well as emerging countries. A government initiative to promote renewable energy has led to a boost in financing in wind power projects. At the end of February 2022, wind power installations accounted for about 10.7% of the installed energy potential of Turkey. The Turkish government forecasts that wind energy will contribute 17.8% to the country’s renewable energy production by 2020. The adoption of renewable energy technologies has exhibited a consistent upward trajectory in the nation’s combined installed capability since 2005. Turkey had successfully installed a total of 10,607 megawatts (MW) of wind energy capacity at the conclusion of 202160. There have been 356 wind energy installations in Turkey, according to the most recent available data.

Solar energy (\(\mathfrak {F}_2\))

It is important to understand that there are multiple parameters that can influence the efficiency of photovoltaic cells and solar thermal technology, which convert sunshine into heat or electric power. The surrounding weather factors, humidity, climate, longitude and altitude statistics are just some of these factors. Approximately 13.4% of Turkey’s overall installed energy production will come from solar energy by 2020. As a result of a trend that began in 2005, this trend has been steadily increasing since then. It has been estimated that solar power house installations alone increased by 7.5 gigawatts between 2013 and September 202161. Turkish solar power houses generated 7816 megawatts (MW) by 2021, exceeding their own target.

Biomass energy (\(\mathfrak {F}_3\))

Organic substances are used in the production of biomass energy in various different types. Manure from animals, industrial sludge, agricultural residues, household solid waste, and sludge from wastewater management are a few types of natural resources. It is important to note that this particular energy system can not only generate, energy, but also allow waste recycling through a variety of different conversion mechanisms simultaneously. Biomass energy is associated with both beneficial and detrimental environmental effects. Consequently, this will reduce greenhouse gas discharges, reduce fossil fuel utilization, and fuel resource security will improve. Sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides are a few types of pollutants that adversely affect the environment. Biomass energy has certain negative effects, but it remains an important ingredient of sustainable energy systems owing to its capabilities of generating energy and dealing with waste62,64,66.

Geothermal energy (\(\mathfrak {F}_4\))

A clean energy source such as geothermal energy has the advantage of obtaining natural heat energy stored in the Earth’s crust. This makes it one of the most popular renewable energy source worldwide. It can generate power continually, all the time, and can deliver reliable power production, which is why geothermal energy is gaining attention globally. Unlike solar and wind energy, which are affected by weather conditions, this source of energy is not affected by weather conditions. A total of 1.3 gigawatts (GW) have been added to geothermal energy’s power output in Turkey between 2013 and September 2021. Approximately three percent of all renewable energy sources came from geothermal sources in September 2021, according to the Department of Energy. In the recent few years, Turkey has gained recognition as one of the world’s most prominent geothermal energy producers, having 63 units in operation as of May 202263. This is shown by the most recent statistics, according to data gathered as of May 2022.

Hydraulic energy (\(\mathfrak {F}_5\))

In Turkey, hydraulic power is an important and valuable renewable energy resource. It is generated by the transformation of potential power into kinetic power. Consequently, the renewable energy production capacity of the country grows tremendously. In general, hydraulic power systems provide the benefit of storing energy for use on a regular or seasonal cycle, as opposed to other kinds of power systems that are dependent on the electrical loads. During heavy demand intervals and the rapid expansion of the economy, this allows the use of energy when necessary. It is true that hydraulic energy systems emit minimal greenhouse gases, but their development still demands an extensive capital commitment. Moreover, they can influence agro-ecological irrigation practices or submerge entire lands that are inhabited by people, thus influencing the environment, land use, and settlement patterns. A major contributor to the 9.2 gigawatts (GW) growth in renewable energy projects from 2013 to September 2021 was hydraulic energy systems64,65,66.

Description of factors associated to RESs

In this part, we will elaborate factors that will help to select the best RE system.

Technical

-

Efficiency (\(\mathfrak {W}_1\)): The efficiency of a system can be calculated by its ability to utilize easily available energy options to satisfy the continually growing need for energy when exchange ratios and operational factors are taken into account. To meet the demands of simultaneously optimizing energy utilization and providing sustainable energy for individual work64, high efficiency is necessary.

-

Lifetime (\(\mathfrak {W}_2\)): Sustainability parameters likewise resource scarcity, economic feasibility, and environmental effects make up the projected lifetime of energy technologies. Their maximum capacity will be reached after a certain period of time. By analyzing this measurement, we can predict that the system will persist to be productive and enable society and the environment to be protected while accommodating future energy needs63.

-

Technology Maturity (\(\mathfrak {W}_3\)): When assessing the progress of technology maturity, it is necessary to determine the level of readiness and accessibility of technology for real-life application. The purpose of this is to determine potential effects and the applicability of technology in solving energy problems65.

Sociopolitic

-

Acceptance (\(\mathfrak {W}_4\)): The level of public acceptance of green initiatives plays an essential role in determining community appreciation for sustainable energy projects and public opinion about existing energy systems related to these initiatives63.

-

National policy (\(\mathfrak {W}_5\)): An integrated approach and effectiveness in accomplishing energy reliability and environmental requirements are ensured through a national energy policy that assesses the extent to which appropriate sources of energy are part of a national energy planning66.

Economic

-

Operational cost (\(\mathfrak {W}_6\)): It is essential to determining the economic feasibility and sustainability of a renewable energy system to analyze the financial obligations of operation and maintenance associated with it67.

-

Economic value (\(\mathfrak {W}_7\)): Several financial parameters can be used to determine a renewable energy source’s economic worth, including discounted net economic value, payback duration, and expected rate of profit60.

Environment

-

Emissions (\(\mathfrak {W}_8\)): There are several components that contribute to the perception of pollutant emissions. The emission reduction values can determine an energy source’s capacity to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and other harmful gases, like nitrogen oxides, carbon dioxide, sulfur oxides and methane64,65.

-

Ecosystem (\(\mathfrak {W}_9\)): An Ecosystem Sustainability assessment measures how an energy system influences a visual appearance, biological diversity, and ecological value64,65,67.

Selection of renewable energy system

As part of this research, we analyze the relative significance of the factors using the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC algorithm for selecting a sustainable renewable energy system. This methodology demonstrated significant efficacy in prioritizing factors by considering real-time situations and incorporating expert insights.

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy CRITIC

As outlined in the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC framework, we take the following steps:

Step 1: An assessment of professionals is conducted and their competence is assessed. Professionals are classified accordingly on educational background and expertise by consulting Table 4. Experts are classified as: one is more skilled, one is fully skilled, two are highly skilled, and they are listed in Table 6. The weight of each professional is computed in accordance with Eq. 10 and corresponding values are \(\mathfrak {P}_1 = 0.2464, \mathfrak {P}_2 = 0.2560, \mathfrak {P}_3 = 0.2512\), and \(\mathfrak {P}_4 = 0.2464\).

Step 2: To evaluate alternatives, decision makers provide assessments based on the significance of predefined criteria. These evaluations are expressed using linguistic variables, which are then converted into FrFNs for quantitative analysis. The corresponding linguistic scale for FrFN conversion is provided in Table 5. Table 7 shows the independent opinions of the experts on alternatives.

Step 3: A combined f, g, h-FrF decision matrix is formed by combining independent expert evaluations. Experts with a greater weight exert a stronger influence on the aggregated outcome. The evaluation of each criteria incorporates all experts’ inputs using Eq. 12 and final outcome s are outlined in Table 8.

Step 4: Calculate decision score matrix using Eq. 14 and values are given in Table 9.

Step 5: In our case \(\mathfrak {W}_6\), \(\mathfrak {W}_8\), and \(\mathfrak {W}_9\) are cost criteria, we convert them into benefit criteria utilizing Eq. 15.

Step 6: Determine the correlation coefficient by applying Eq. 16 which reflects the extent to which one criterion is associated with the other. The correlation coefficients between all the criteria are calculated and shown in Fig. 3.

Step 7: Equation 17 is utilized to determine standard deviation.

\(\{0.3629, 0.3197, 0.3437, 0.3828, 0.3436, 0.3731, 0.3557, 0.3502, 0.3474\}\)

Step 8: Equation 18 is utilized to determine the information index.

\(\{2.7328, 2.6452, 3.2980, 3.4076, 3.5824, 2.7852, 3.2726, 2.8531, 2.8600\}\)

Step 9: Compute the final weights by employing Eq. 19.

\(\{0.0996, 0.0964, 0.1202, 0.1242, 0.1306, 0.1015, 0.1193, 0.1040, 0.1042\}\)

f, g, h-fractional fuzzy WASPAS

As outlined in the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC framework, we take the following steps:

Step 10: Collect insights from a panel of individuals responsible for making decisions regarding the potential for sustainable renewable energy systems. This depends on how significant the criteria are. Information collected with the help of Table 5 and the evaluation results provided by the decision-makers can be orderedly organized into y decision matrices as Eq. 20.

Step 11: A combined decision matrix for f, g, h-FrF is constructed by combining independent expert evaluations. Assessment of each criteria by consolidating the evaluations of all experts through Eq. 21, with the resulting combined matrix expressed in Table 8.

Step 12: The SAW algorithm is employed to Table 8 by integrating the criterion weights to compute the \(\widehat{SAW}\) f, g, h-FrF scores of all systems using Eq. 23. Table 10 yielded the final output of \(\widehat{SAW}\) operator.

Step 13: The weighted measurements for each characteristic of RES are aggregated through an addition operation as specified in Eq. 24.

Step 14: The WPM algorithm is employed to \( \mathscr{E}^{agg}\) by integrating the criterion weights to compute the \(\widehat{WPM}\) f, g,h-FrF scores of all systems using Eq. 25 Table 11 yielded the final output of \(\widehat{WPM}\) operator.

Step 15: The product algorithm is applied to compute the product of the respective assessments for each factor, as represented by Eq. 26.

Step 16: The threshold number \(\Gamma = 0.5\) is applied to the f, g, h-fractional fuzzy values of WPM and SAW in order to incorporate their fractional fuzzy values. As a result of applying Eq. 27, we are able to determine the result of each alternative and final outputs are outlined in Table 12.

Step 17: The optimal option should be determined by sorting the options in descending sequence and the geothermal energy system is the optimal option. The ranking of RE systems is shown in Fig. 4.

Performance evaluation metrics

Incomplete reliability compromises the efficacy of collective information. It is imperative to use a set of measurement metrics within the algorithmic methodology of f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS to determine its consistency, accuracy, and robustness. To accomplish this task, this section utilizes some measurement metrics.

Comparative analysis

Table 13 illustrates the comparative evaluation of multiple decision-making approaches that are implemented in the fuzzy environment. As a result of these techniques, picture fuzzy WASPAS (PcF WASPAS)68, IF WASPAS69, Fuzzy WASPAS70, and the suggested f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS have been incorporated into the analysis. The optimal system, though, is constantly validated as \(\mathfrak {F}_4\) in all techniques and is systematically determined to be the best. A ranking of RESs is presented in Fig. 5 for all techniques, and the proposed model values have a narrow interval, so you can refer to Fig. 4 for details. When confronting multifaceted decision environments within the fuzzy framework, \(\mathfrak {F}_4\) consistently makes the optimal choice, which validates its durability and robustness. In addition, it confirms the versatility and effectiveness of \(\mathfrak {F}_4\) under a variety of decision-making scenarios. Referring to Table 13, we examine how the rankings of the developed method correlate with those obtained using other approaches suggested in previous research. An optimal solution is identified using a f, g, h-FrF-based model. In this comparison, the rankings from other methods tend to be consistent and support the selection of the most suitable alternative. However, discrepancies in the rankings are observed, which might be attributed to a lack of complete data or inherent variability when considering the various criteria weights. Our analysis indicated that \(\mathfrak {F}_4\) is consistently identified as the most suitable alternative according to the proposed MCDM framework. This conclusion aligns with the results from other methods. This further confirms the efficiency and accuracy of the proposed decision-making methodology.

In this research, our objective is to investigate the complex problem of identifying the best energy alternatives for sustainable development. Our framework is designed to optimize renewable energy utilization to accomplish this goal. This research provides an all-encompassing method for investigating various renewable energy solutions, considering a wide array of parameters that cover technological, social, economic, political, and ecological factors. The alternatives explored include wind, biomass, hydroelectric, solar, and geothermal energy, representing the diverse renewable energy possibilities attainable to Turkey. By conducting a detailed evaluation of each option in terms of its technical viability, economic feasibility, social acceptance, and environmental impact, we can gain a clear understanding of how each alternative might contribute to the country’s power sector. The decision-making procedure involved in adopting renewable energy is inherently complex, as it involves multiple criteria such as system efficiency, public support, lifespan, alignment with national policies, technological maturity, operational and maintenance costs, economic benefits, pollutant emissions, and environmental effects. This research develops an appropriate evaluation system for renewable energy sources by combining the CRITIC and WASPAS models in an integrated f, g, h-fractional fuzzy approach.

One of the primary advantages of the proposed model involves in its capabilities to accommodate inherent complexity and ambiguity in decision-making mechanisms. Conventional fuzzy sets are limited in their ability to adequately manage complex, real-world data, especially when the power sum of NMB, ID, and MB exceeds their constraints. The (f, g, h-FrF) framework, on the other hand, provides enhanced flexibility, allowing for data representation that traditional fuzzy sets cannot accommodate. Unlike conventional MCDM methods, the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS approach is effective at managing the nuanced complexities of modern industrial systems, especially those encountered in Industry 4.0 contexts. Geothermal energy (F4) ranking as the most viable option across all approaches in our comparative analysis further illustrates the superiority of our model. By integrating an advanced fuzzy logic system, the model can better handle geothermal energy sustainability. This makes it a more reliable tool for long-term energy assessments.

Moreover, to substantiate the accuracy and consistency of the formulated methodology, the Spearman correlation test and the sensitivity analysis were employed. The results show that our methodology consistently outperforms these alternative approaches in terms of decision-making accuracy and robustness, especially in the domain of environmentally friendly energy solutions in Industry 4.0.

Spearman rank correlation

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient serves as a nonparametric measure for evaluating numerical associations among two factors71. By employing a monotonic function, it determines the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables. Spearman coefficients72 can be calculated using the following formula:

According to \(d_t=(M_t - E_t)\), when comparing the ranks of the t-th data set in the two parameters, there is a difference among their ranks represented by “d”. Where \(M_t\) denotes the rank of the t-th measurement of the first data set. \(E_t\) denotes the rank of the t-th measurement of the second data set, and n signifies the total number of measurements (data set).

Applying the Spearman rank correlation to Table 13, we evaluate the similarities among the rank results produced using the developed algorithm and the chosen comparative methods. The obtained Spearman correlation coefficients of the developed algorithm against the compared methods are 0.9, 0.9, 0.9, indicating a very strong positive monotonic relationship between each method. As coefficients are close to 1 (such as 0.9), suggesting a high level of ranking similarity. The complete set of Spearman correlation values among all methods is illustrated in Fig. 6, presenting a graphical illustration of the strength of correlation between the compared techniques.

Sensitivity analysis

To investigate how FrF-based CRITIC-WASPAS is implemented and how it influences rankings, adjust \(\Gamma\) to perform a sensitivity analysis. Through this approach, the proposed methodology demonstrates its stability and effectiveness by alleviating the uncertainty commonly encountered in data extraction and assessment.

Our calculations use a fixed value of \(\Gamma\) = 0.5 to calculate the utility function for each alternative. Utility values determine the ranking order of RESs based on their performance. A WASPAS method simplifies an equation containing \(\Gamma\) = 0 to a WPM equation, and another equation containing \(\Gamma\) = 1 to a SAW equation. If \(\Gamma\) is between 0 and 1 (such as 0.1, 0.2, 0.3,...,0.9), the method essentially combines both models. All \(\delta\) values result in relatively uniform rankings and \(\mathfrak {F}_4\) consistently ranks as the most effective RE system. The stability of rankings observed in the sensitivity analysis suggests that the proposed model is indeed more resilient to variations in individual judgment. This is a common source of bias in decision-making processes. In real-world applications, experts may have different perceptions, experiences, or preferences that can affect the ranking of alternatives. Our model’s ability to maintain consistent rankings, even when expert input is altered, indicates that it can mitigate individual bias. This characteristic is particularly valuable in decision-making contexts with diverse expert viewpoints, such as in Industry 4.0 assessments of renewable energy sources (RES). The sensitivity analysis also demonstrates that the model is less sensitive to small fluctuations in the input data, which indicates a high degree of robustness to uncertainty. Therefore, the model’s stability enhances its reliability and trustworthiness in real-world scenarios where bias may be a concern. An overview of the results of this sensitivity analysis, as well as a ranking of alternatives, can be found in Table 14. Figure 7 provides a visualization of the relationship between \(\delta\) and the ranking of alternatives.

Discussion

A major challenge when optimizing RES for Turkey is identifying an appropriate energy option among several achievable solutions. With the growing global focus on greenhouse gas minimization and environmental protection, the Turkish government faces the task of meeting its power demands while aligning towards the SDGs as committed to51. This challenge is becoming increasingly difficult to tackle. One significant factor contributing to this challenge is Turkey’s membership in the United Nations, which adds complexity to the decision-making process. In addition, balancing high technical performance alongside financial feasibility, public acceptance, and ecological impacts complicates the task even further. The need to consider all of these factors introduces uncertainty and complicates the decision-making process.

To address these complexities, an integrated decision-making framework, known as the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS framework, was implemented. This model uses the CRITIC approach to assess the interrelationship between criteria and evaluates possible solutions based on the WASPAS approach. The CRITIC approach plays a crucial role in objectively weighing each criterion according to its strength relative to their correlation coefficient and standard deviation. By doing this, the decision-making methodology effectively reflects the significance of each criterion. In addition to the CRITIC method, the WASPAS approach prioritizes the possible solutions by combining weighted criteria and dual aggregation of SAW and WPM models. This process ensures that the ranking is both objective and comprehensive, considering both technical and non-technical aspects of each alternative. To refine these weights further, the CRITIC method also integrates expert judgment. This allows for the inclusion of personal preferences and insights hidden in the raw data. This approach fine-tunes the decision-making process, aligning it with real-world priorities. The outcomes are summarized by Alkan57, Jameel et al.59, and Bilgili et al.73 are consisted with the results obtained. By utilizing both CRITIC and WASPAS, this methodology provides a balanced, effective, and reliable framework to determine the optimally suitable renewable energy alternatives for Turkey.

Final outcomes of the developed model indicate that geothermal energy is the optimal renewable energy source in Turkey relative to the available renewable energy sources (RES). This conclusion is the result of the methodology’s capability to incorporate a broad collection of factors, including technical performance, social acceptability, cost-effectiveness, and environmental impact. Geothermal energy offers numerous advantages, such as minimal environmental impact, widespread societal recognition, and low operational and service costs. These are just some of the many positive aspects that geothermal energy provides. Furthermore, we performed a sensitivity analysis which provided additional evidence of the efficiency and robustness of the developed methodology. The analysis demonstrated that geothermal energy performed well across various scenarios with changes in critical criteria. The results highlighted geothermal energy’s high operational success rate, demonstrating the methodology’s resilience to fluctuations in raw data statistics. This robustness strengthens the reliability of the methodology, enhancing its value as a decision-making tool under dynamic, ever-changing situations. To further examine the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS methodology in relation to comparable existing fuzzy MCDM methodologies, both comparative and sensitivity analyses were employed. Compared to conventional evaluation methodologies , the CRITIC-WASPAS methodology integrates both expert opinion and objective data to provide a comprehensive assessment framework. This approach enables a more comprehensive analysis, yielding more accurate results and fostering a more effective decision-making process.

Managerial implications

Energy managers and policymakers in Turkey seeking to optimize RES can gain useful information with the findings of this research. There are several key implications to note, including:

-

The proposed f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-WASPAS methodology integrates multiple decision-making methods, offering a robust tool to evaluate and select the most suitable RES options. Through the CRITIC method, critical criteria like technical performance, environmental impact, and social acceptability are weighted objectively. This ensures decision-makers have a comprehensive view of all factors influencing RES selection.

-

Geothermal energy emerged as the most favorable RES option for Turkey, primarily due to its minimal environmental impact, cost-effectiveness, and societal acceptance. Managers and policymakers can prioritize geothermal energy for future investments in sustainable energy infrastructures. Given its advantages, it can play a key role in achieving Turkey’s SDGs while meeting its energy needs.

-

As a result of this study’s sensitivity analysis, it highlights that the methodology that has been developed is robust. This adaptability ensures that decision-makers can rely on the model in dynamic and uncertain environments, where input parameters such as cost and environmental criteria may fluctuate over time. This feature is critical for planning long-term sustainable solutions.

-

National policy guidelines and international commitments, such as those to the United Nations SDGs, should guide RES adoption in Turkey. The energy sector, in collaboration with policymakers, should ensure that selected energy alternatives not only meet immediate energy demands but also align with Turkey’s broader sustainability and environmental objectives.

-

Geothermal energy’s performance across various scenarios underlines its suitability as a long-term solution. Sectors looking for a sustainable, cost-effective energy source should consider geothermal energy as an optimal option, given its strong operational success rate even under varying input conditions.

-

Comparative analysis has demonstrated improvements in decision-making accuracy and reliability. The framework’s ability to incorporate both objective data and expert opinions makes it an invaluable tool for evaluating RES alternatives. This provides clearer insights into the most effective energy options for Turkey’s energy sector.

Conclusion

A systematic methodology for optimizing Turkey’s Renewable Energy Sources (RES) has been proposed, considering a broad spectrum of technological, financial, social, and ecological parameters. With regard to the integrated f, g, h-FrF-CRITIC-WASPAS methodology presented in this study, the CRITIC method identifies technology maturity, economic benefits, and national policy as the most influential criteria for assessing the relative importance of RES, while the WASPAS method recommends geothermal energy as the optimal RES. For Turkey to fulfill its energy requirements and make a contribution to worldwide environmental change mitigation actions, adopting renewable energy technologies that align with the nation’s SDGs is crucial. The investigation underscores the significant role of the parameter \(\Gamma\) in decision-making, emphasizing \(\mathfrak {F}_4\) as the most suitable solution owing to stable and reliable performance in a broad range of circumstances. As a result of this enlightenment, decision-makers are able to make better judgements when dealing with various scenarios. To ensure the long-term efficiency and scalability of renewable energy solutions, it is essential to monitor their progress and invest in increasing their efficiency and durability. In summary, the findings of this research offer critical support for various stakeholders working together to achieve a secure and sustainable energy supply system for Turkey and the global community. In Industry 4.0, energy planning and development is complicated, so this tool can help manage the complexities.

It is important to note a certain limitations in the developed RES evaluation methodology, which integrates the f, g, h-FrF-CRITIC-WASPAS approach. The primary limitation of this research is the participation of only one decision expert in each dimension, which increases the risk of misjudging certain criteria or alternatives. Additionally, the arithmetic operations of fractional fuzzy numbers are more complex than fuzzy or crisp numbers, which poses challenges in calculations. Moreover, the model’s application is currently limited to RES evaluation, which may not sufficiently validate the results.

The inclusion of a wide group of experts from each domain has the potential to enhance the evaluation process and improve its accuracy. Developing computational techniques to automate processes and computations can reduce the time and effort of experts. Additionally, the proposed methodology can be utilized for addressing multifaceted emerging problems in various areas such as medical waste treatment74, agricultural reforms75, and disaster management76.

Data availability

The data used in this study is included in the article. Further inquiries are directed to the corresponding author.

Change history

13 January 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the affiliation ' School of Mathematics, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing 210016' was incorrectly given as ‘School of Mathematics, Nanjing University of Astronautics and Aeronautics, Nanjing 210016.’ The original article has been corrected.

13 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23632-5

References

Habiba, U., Xinbang, C. & Anwar, A. Do green technology innovations, financial development, and renewable energy use help to curb carbon emissions?. Renew. Energy 193, 1082–1093 (2022).

Umar, M. & Safi, A. Do green finance and innovation matter for environmental protection? A case of OECD economies. Energy Econ. 119, 106560 (2023).

Habiba, U. & Xinbang, C. The contribution of different aspects of financial development to renewable energy consumption in E7 countries: The transition to a sustainable future. Renew. Energy 203, 703–714 (2023).

Ezbakhe, F. & Pérez-Foguet, A. Decision analysis for sustainable development: The case of renewable energy planning under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 291(2), 601–613 (2021).

Fund, S. Sustainable development goals, Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/inequality (2015).

Liang, C., Umar, M., Ma, F. & Huynh, T. L. Climate policy uncertainty and world renewable energy index volatility forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 182, 121810 (2022).

Habiba, U., Xinbang, C. & Ali, S. Investigating the impact of financial development on carbon emissions: Does the use of renewable energy and green technology really contribute to achieving low-carbon economies?. Gondwana Res. 121, 472–485 (2023).

Ellabban, O., Abu-Rub, H. & Blaabjerg, F. Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 39, 748–764 (2014).

Kutlu Gündoğdu, F. & Kahraman, C. Spherical fuzzy sets and spherical fuzzy TOPSIS method. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 36(1), 337–352 (2019).

Mahmood, T., Ullah, K., Khan, Q. & Jan, N. An approach toward decision-making and medical diagnosis problems using the concept of spherical fuzzy sets. Neural Comput. Appl. 31, 7041–7053 (2019).

Gulistan, M. et al. \(p, q, r-\) Fractional fuzzy sets and their aggregation operators and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(12), 1–29 (2024).

Sarwar, M. A., Gong, Y., Alzakari, S. A. & Alhussan, A. A. A novel Fractional fuzzy approach for multi-criteria decision-making in medical waste management. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 23999 (2025).

Lo, H. W. A novel interval neutrosophic-based group decision-making approach for sustainable development assessment in the computer manufacturing industry. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 132, 107984 (2024).

Aydin, N., Seker, S., Deveci, M. & Zaidan, B. B. Post earthquake debris waste management with interpretive-structural-modeling and decision-making-trial, and evaluation-laboratory under neutrosophic fuzzy sets. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109251 (2024).

Zhang, C., Yang, G., Wang, C. & Huo, Z. Linking agricultural water-food-environment nexus with crop area planning: A fuzzy credibility-based multi-objective linear fractional programming approach. Agric. Water Manag. 277, 108135 (2023).

Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 8(3), 338–353 (1965).

Atanassov, K.T. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets, fuzzy sets and systems (1986).

Garg, H., Munir, M., Ullah, K., Mahmood, T. & Jan, N. Algorithm for T-spherical fuzzy multi-attribute decision making based on improved interactive aggregation operators. Symmetry 10(12), 670 (2018).

Diakoulaki, D., Mavrotas, G. & Papayannakis, L. Determining objective weights in multiple criteria problems: The critic method. Comput. Oper. Res. 22(7), 763–770 (1995).

Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M., Amiri, M., Kazimieras Zavadskas, E. & Antuchevičienė, J. Assessment of third-party logistics providers using a CRITIC–WASPAS approach with interval type-2 fuzzy sets. Transport 32(1), 66–78 (2017).

Rostamzadeh, R., Ghorabaee, M. K., Govindan, K., Esmaeili, A. & Nobar, H. B. K. Evaluation of sustainable supply chain risk management using an integrated fuzzy TOPSIS-CRITIC approach. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 651–669 (2018).

Tuş, A. & Aytaç Adalı, E. The new combination with CRITIC and WASPAS methods for the time and attendance software selection problem. Opsearch 56, 528–538 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Site selection decision framework for photovoltaic hydrogen production project using BWM-CRITIC-MABAC: A case study in Zhangjiakou. J. Clean. Prod. 324, 129233 (2021).

Asante, D. et al. Prioritizing strategies to eliminate barriers to renewable energy adoption and development in Ghana: A CRITIC-fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Renew. Energy 195, 47–65 (2022).

Akram, M., Ramzan, N. & Deveci, M. Linguistic Pythagorean fuzzy CRITIC-EDAS method for multiple-attribute group decision analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105777 (2023).

Menekşe, A. & Akdağ, H. C. Medical waste disposal planning for healthcare units using spherical fuzzy CRITIC-WASPAS. Appl. Soft Comput. 144, 110480 (2023).

Akram, M., Zahid, S. & Deveci, M. Enhanced CRITIC-REGIME method for decision making based on Pythagorean fuzzy rough number. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122014 (2024).

Akram, M., Azam, S., Al-Shamiri, M. M. A. & Pamucar, D. An outranking method for selecting the best gate security system using spherical fuzzy rough numbers. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109411 (2024).

Stanujkić, D. & Karabašević, D. An extension of the WASPAS method for decision-making problems with intuitionistic fuzzy numbers: A case of website evaluation. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 1(1), 29–39 (2018).

Aydoğdu, A. & Gül, S. A novel entropy proposition for spherical fuzzy sets and its application in multiple attribute decision-making. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 35(9), 1354–1374 (2020).

Yücenur, G. N. & Ipekçi, A. SWARA/WASPAS methods for a marine current energy plant location selection problem. Renew. Energy 163, 1287–1298 (2021).

Ayyildiz, E., Erdogan, M. & Taskin Gumus, A. A Pythagorean fuzzy number-based integration of AHP and WASPAS methods for refugee camp location selection problem: A real case study for Istanbul, Turkey. Neural Comput. Appl. 33(22), 15751–15768 (2021).

Ghoushchi, S. J. et al. Landfill site selection for medical waste using an integrated SWARA-WASPAS framework based on spherical fuzzy set. Sustainability 13(24), 13950 (2021).

Al-Barakati, A., Mishra, A. R., Mardani, A. & Rani, P. An extended interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy WASPAS method based on new similarity measures to evaluate the renewable energy sources. Appl. Soft Comput. 120, 108689 (2022).

Senapati, T. & Chen, G. Picture fuzzy WASPAS technique and its application in multi-criteria decision-making. Soft. Comput. 26(9), 4413–4421 (2022).

Dhumras, H. & Bajaj, R. K. On potential strategic framework for green supply chain management in the energy sector using q-rung picture fuzzy AHP & WASPAS decision-making model. Expert Syst. Appl. 237, 121550 (2024).

Eti, S. et al. A machine learning and fuzzy logic model for optimizing digital transformation in renewable energy: Insights into industrial information integration. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 42, 100734 (2024).

Rostamzadeh, R., Ghorabaee, M. K., Govindan, K., Esmaeili, A. & Nobar, H. B. K. Evaluation of sustainable supply chain risk management using an integrated fuzzy TOPSIS-CRITIC approach. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 651–669 (2018).

Pathak, R., Soni, B., Muppalaneni, N. B. & Deveci, M. Interval-valued q-rung orthopair fuzzy complex proportional assessment-based approach and its application for evaluating the factors of blockchain technology in various domains. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 42, 100718 (2024).

Ghorabaee, M. K., Amiri, M., Zavadskas, E. K. & Antucheviciene, J. A new hybrid fuzzy MCDM approach for evaluation of construction equipment with sustainability considerations. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 18, 32–49 (2018).

Ke, Y., Liu, J., Meng, J., Fang, S. & Zhuang, S. Comprehensive evaluation for plan selection of urban integrated energy systems: A novel multi-criteria decision-making framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 81, 103837 (2022).

Tronnebati, I., Jawab, F., Frichi, Y. & Arif, J. Green supplier selection using fuzzy AHP, fuzzy TOSIS, and fuzzy WASPAS: A case study of the Moroccan automotive industry. Sustainability 16(11), 4580 (2024).

Zavadskas, E. K., Turskis, Z., Antucheviciene, J. & Zakarevicius, A. Optimization of weighted aggregated sum product assessment. Elektronika ir elektrotechnika 122(6), 3–6 (2012).

Rudnik, K., Bocewicz, G., Kucińska-Landwójtowicz, A. & Czabak-Górska, I. D. Ordered fuzzy WASPAS method for selection of improvement projects. Expert Syst. Appl. 169, 114471 (2021).

Singh, T. Entropy weighted WASPAS and MACBETH approaches for optimizing the performance of solar water heating system. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 53, 103922 (2024).

Khalid, M. Smart grids and renewable energy systems: Perspectives and grid integration challenges. Energy Strat. Rev. 51, 101299 (2024).

Hassan, Q. et al. The renewable energy role in the global energy Transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 48, 100545 (2024).

Assadi, M. R., Ataebi, M., Sadat Ataebi, E. & Hasani, A. Prioritization of renewable energy resources based on sustainable management approach using simultaneous evaluation of criteria and alternatives: A case study on Iran’s electricity industry. Renew. Energy 181, 820–832 (2022).

Abdel-Basset, M., Gamal, A., Chakrabortty, R. K. & Ryan, M. J. Evaluation approach for sustainable renewable energy systems under uncertain environment: A case study. Renew. Energy 168, 1073–1095 (2021).

Yürek, Y. T., Bulut, M., Özyörük, B. & Özcan, E. Evaluation of the hybrid renewable energy sources using sustainability index under uncertainty. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 28, 100527 (2021).

Büyüközkan, G., Karabulut, Y. & Mukul, E. A novel renewable energy selection model for United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Energy 165, 290–302 (2018).

Li, T., Li, A. & Guo, X. The sustainable development-oriented development and utilization of renewable energy industry-A comprehensive analysis of MCDM methods. Energy 212, 118694 (2020).

Mostafaeipour, A., Hosseini Dehshiri, S. J., Hosseini Dehshiri, S. S., Jahangiri, M. & Techato, K. A thorough analysis of potential geothermal project locations in Afghanistan. Sustainability 12(20), 8397 (2020).

Ghenai, C., Albawab, M. & Bettayeb, M. Sustainability indicators for renewable energy systems using multi-criteria decision-making model and extended SWARA/ARAS hybrid method. Renew. Energy 146, 580–597 (2020).

Goswami, S. S., Mohanty, S. K. & Behera, D. K. Selection of a green renewable energy source in India with the help of MEREC integrated PIV MCDM tool. Mater. Today Proc. 52, 1153–1160 (2022).

Esangbedo, M. O. & Tang, M. Evaluation of enterprise decarbonization scheme based on grey-MEREC-MAIRCA hybrid MCDM method. Systems 11(8), 397 (2023).

Alkan, N. Evaluation of sustainable development and utilization-oriented renewable energy systems based on CRITIC-SWARA-CODAS method using interval valued picture fuzzy sets. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 38, 101263 (2024).

Alyamani, R., Solangi, Y. A., Almakhles, D. & Alyami, H. H. Analysis of solution strategies for the transition to renewable energy in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Energy 235, 121400 (2024).

Jameel, T., Riaz, M., Aslam, M. & Pamucar, D. Sustainable renewable energy systems with entropy based step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis and combined compromise solution. Renew. Energy 235, 121310 (2024).

Saraswat, S. K. & Digalwar, A. K. Evaluation of energy alternatives for sustainable development of energy sector in India: An integrated Shannon’s entropy fuzzy multi-criteria decision approach. Renew. Energy 171, 58–74 (2021).

Alsattar, H. A. et al. Developing IoT sustainable real-time monitoring devices for food supply chain systems based on climate change using circular intuitionistic fuzzy set. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(16), 26680–26689 (2023).

Büyüközkan, G., Karabulut, Y. & Mukul, E. A novel renewable energy selection model for United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Energy 165, 290–302 (2018).

Alkan, N. Evaluation of sustainable development and utilization-oriented renewable energy systems based on CRITIC-SWARA-CODAS method using interval valued picture fuzzy sets. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 38, 101263 (2024).

Abdel-Basset, M., Gamal, A., Chakrabortty, R. K. & Ryan, M. J. Evaluation approach for sustainable renewable energy systems under uncertain environment: A case study. Renew. Energy 168, 1073–1095 (2021).

Ezbakhe, F. & Pérez-Foguet, A. Decision analysis for sustainable development: The case of renewable energy planning under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 291(2), 601–613 (2021).

Yürek, Y. T., Bulut, M., Özyörük, B. & Özcan, E. Evaluation of the hybrid renewable energy sources using sustainability index under uncertainty. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 28, 100527 (2021).

Ghenai, C., Albawab, M. & Bettayeb, M. Sustainability indicators for renewable energy systems using multi-criteria decision-making model and extended SWARA/ARAS hybrid method. Renew. Energy 146, 580–597 (2020).