Abstract

This study examines whether integrating sports and arts interventions enhances response joint attention (RJA) in children with mild autism and provides insights for diversifying intervention strategies for autism. 2024.6–2024.12,Twenty-four children with autism, aged 6–12 years, were recruited from an autism association in Anhui Province, China. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated sequence (allocation concealed from assessors) assigned to an experimental group (n = 12) or a control group (n = 12). Over 12 weeks, the experimental group participated in basketball and drawing lessons four times a week for 60 min per session, while the control group engaged only in routine activities and structured teaching provided by their school and the association. RJA performance was assessed pre- and post-intervention using eye-tracking technology, analyzing key metrics: time to first fixation (TFF), fixation count (FC), total fixation duration (TFD), total visit duration (TVD), visit count (VC), and the ratio of correct to incorrect for first responses. Post-intervention, the experimental group showed significantly greater improvements in RJA performance than the control group. Key metrics for the experimental group included TFF (0.52 ± 0.79), FC (36.35 ± 6.34), TFD (11.05 ± 1.33), TVD (17.05 ± 2.33), VC (24.25 ± 2.49), and correct-to-incorrect ratio (1.1 ± 0.1), all of which outperformed the control group: TFF (0.59 ± 0.11), FC (30.83 ± 2.14), TFD (9.47 ± 1.38), TVD (15.42 ± 1.51), VC (20.33 ± 1.87), and correct-to-incorrect ratio (0.97 ± 0.08),partialη2 ranged from 0.25 to 0.78, with P < 0.05. Integrating sports and arts interventions significantly improves RJA in children with autism, highlighting the potential of these methods in enhancing attention-related behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism, known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a neurodevelopmental disorder. The autism group is characterized by social communication deficits, narrow interests, and repetitive stereotyped behaviors1. Nowadays, autism has become one of the fastest-growing developmental disability in the world, and the means of diagnosis and rehabilitation of autistic children has become a public health issue that requires urgent attention2. Joint attention (JA) refers to the shared focus of two individuals on an object or event to exchange interest or experiences (e.g., a child following a parent’s gaze toward a toy). This skill is foundational for social-cognitive development3. Joint attention includes responding joint attention (RJA) and initiating joint attention (IJA), of which deficits in RJA are considered to be a direct manifestation of social impairment in children with ASD, while deficits in RJA can directly affect the social development of children with ASD. RJA deficits can directly affect children with ASD’s language acquisition, environmental adaptation, and social skills4. Studies have shown that joint attention deficits play an important role in explaining the pathogenesis of ASD5, and that early intervention plays an important role in the language and social cognitive development of children with ASD6. Early intervention plays an important role in the language and social-cognitive development of children with ASD. Current clinical interventions prioritize music, games, peer interactions, and physical activities7. However, most studies compare isolated interventions rather than integrated approaches8. The majority of researchers have used one or more interventions as the blueprint for their experiments. A large number of studies have found that the integration of educational tools as an early intervention treatment can give full play to its joint effect, stimulate the interest of participants, and at the same time show a stronger therapeutic effect than single-activity interventions9. Existing convergent studies have focused on early education and sensory training, and few have been based on strictly controlled randomized controlled trials. Based on the summarization of previous studies, this experiment used the combination of basketball activities and drawing art, which has been widely proven to have a strong intervention effect on children with ASD, as the intervention means to explore the feasibility of combining physical activities and drawing art10,11. The present experiment used the combination of basketball and drawing art as an intervention, which has been widely proven to have strong effects on children with ASD.

Methods

Participants

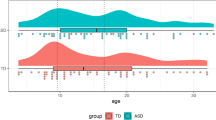

In this study, from 2024.6 to 2024.12, children with ASD were recruited from an autism association in a city in Anhui Province. Inclusion criteria: aged 6–12 years old, possessing a diagnostic certificate of autism issued by the association or a tertiary hospital, and not having received basketball training or drawing courses. Exclusion criteria: physical movement disorders, epilepsy or other sudden illnesses, violent tendencies, audiovisual disorders. Exclusion and exclusion criteria: inability to participate in the full training program, voluntary request to withdraw from the study in the middle of the study.

According to the above criteria, a total of 30 children with autism were recruited, but of which 3 parents indicated that the intervention site was far away and could not attend on time, 2 had epilepsy or osteochondritis dissecans, and 1 had a visual impairment, so the final number of autistic children participating in the study was 24. All participants were randomly grouped according to the random number table method, with 12 in the control group (7 males/5 females) and 12 in the experimental group (6 males/6 females). All participants demonstrated functional language (e.g., ≥ 5-word sentences) and followed 2-step instructions, confirmed via parent-reported.There was no statistically significant gender difference between the two groups (χ2 = 0.168, P = 0.682 > 0.05). The experimental group participated in a 12-week behavioral intervention of basketball training and painting art in addition to receiving conventional rehabilitation therapy, four times a week, including two basketball sessions and two painting sessions each, 60 min/session. Meanwhile the control group did not participate in any physical activity of the same type,and only engaged in regular activities included school-led structured teaching (e.g., picture-exchange communication, sensory integration drills) and association-provided social skills groups.Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the study participants prior to their participation in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. For research involving human participants, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.Identifying information has been removed to ensure privacy.The demographics of the experimental subjects were analyzed in Table 1. The flow of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 1.

Program design

This study is based on the multi-path theory of sports to promote children’s brain intelligence development12 and also refers to the existing research results, combines the characteristics and development trend of autistic children13,14, a set of integration intervention program was designed. The intervention program is shown in Table 1.

Quality control

In this experiment, the load of the basketball class was arranged to be of medium intensity, and three subjects were randomly arranged to wear heart rate monitors in each class to control their heart rate at 50% to 70% of the maximum heart rate. If a participant’s heart rate falls below or exceeds the preset range, the head coach shall appropriately adjust the participant’s training pace to ensure compliance with the estimated intensity; the teaching place of the basketball class and the painting art class was arranged in the open and safe basketball court and classroom; the basketball teaching team was arranged to be four postgraduates majoring in physical education with physical education teacher qualification certificates, and the painting teaching team was arranged to be four postgraduates majoring in art with art teacher qualification certificates. At the same time, parents or guardians are arranged to accompany the subjects throughout the course,parents are required to sign in before each class begins. The attendance rate of parents throughout the entire experiment was 100%.

Eye movement feature acquisition

Experimental apparatus and operation

In the assessment room of the autism association where the participants were located, a Tobii Pro Fusion portable eye-tracker (which works by recording the binocular gaze points of near-infrared light reflected on the cornea and pupil) and a laptop computer with Tobii Pro Lab software were used as the experimental apparatus components. The resolution ratio of the computer’s screen was set to 1920 × 1080 pixels, and the eye-tracker was set below the laptop screen. the distance between the participants and the screen was controlled to be 50 cm(with an up-and-down error of 10 cm), and the permissible head-movement degrees of freedom interval was 45 cm × 25 cm × 30 cm. The study used the cartoon vocalizations that came with Tobii Studio to attract the participants’ gaze and thus perform the calibration of the device. The sampling accuracy was 0.5°, and the frequency was 120 Hz. Children whose attention was disengaged during the test were reminded in time, and if they were not able to fully cooperate to complete the test, a supplementary test was conducted, and after completing the experiment, the participants were rewarded with verbal compliments and snacks.

Stimulus material for eye movement experiments

The RJA eye movement paradigm in this study was modified based on the NYSTRM study15,16. The experimental stimulus materials were a plain white background and a female model with a red-colored apple on the left side of the model’s head and a green apple on the right side of the model’s head (both apples were of the same size and shape), and there were a total of three types of cues pointing to one of the apples, which were as follows: (1) Eye cues: the model’s head and body remained stationary, and her eyes gazed at the target apple. (2) Head-turning cue: the model’s body remained still and her head was turned towards the target. (3) Head turning + gesture cue: the model’s head was turned towards the target apple and the gesture was directed towards the target. The vertical and horizontal positions of the model and the apple remained the same under different types of cues.

Flow of the eye movement experiment

Before the start of each test, a “+ ”-like gaze point with a duration of 1000 ms was presented in the center of the screen, and then the stimulus picture materials were presented sequentially, and a “ + ” with a duration of 1000 ms was presented between different types of cue presentations, the duration of each stimulus was 3000 ms. And the total duration of the experiment was 48 s. The specific flow is shown in Fig. 2.

Observational indicators of eye movement experiments

The screen was divided into a total of three regions of interest: the cue area (A1): the area where the model was located when the cue was presented; the target area (A2): the area to which the cue was directed; and the interference area (A3): the area to which the cue was not directed.

Eye tracking will extract the following analytic metrics: ①Time to First Fixation (TFF): the time between the presentation of the stimulus material and the first time the subject’s gaze enters area A1. ②Fixation count (FC): the total number of times the subject fixated on areas A1 and A2. ③Total Fixation Duration (TFD): the sum of the subjects’ fixation time on area A1. ④Total Visit Duration (TVD): the sum of the time between the first time the subject’s gaze entered area A1 and the last time the subject left area A1. ⑤Visit Count (VC): the sum of blinks and sweeps between the first time the participants’ gaze went to the A1 and A2 areas and the last time it left the area of interest. ⑥The ratio of correct to incorrect for first response: the total number of times the subject first gazed at area A2 divided by the total number of times the subject first gazed at the other area17. The division of the regions of interest is shown in Fig. 3.

Behavioral indicators

Subjects were retested using the CARS scale, the Autism Rating Scale (CARS), developed by Schopler et al. for individuals with ASD from childhood through adulthood18. The scale consists of 15 assessment items, each of which is rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 4, with a total score of 60. The score results reflect the severity of autism: scores below 30 indicate no autism symptoms, scores between 30 and 35 are considered mild to moderate autism, and scores above 35 indicate severe autism. The present study was a homogeneous test of the degree of developmental disability in the 2 groups of children based on their CARS scores.

Statistical methods

The collected data were statistically analyzed using spss27.0. The demographics of the subjects were first analyzed with descriptive statistics, measures were expressed as mean plus minus standard deviation (M ± SD), and count data were compared for differences using chi-square test. The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed normality, justifying parametric tests over non-parametric alternatives for this small sample. Post-hoc power analysis revealed adequate power, and then independent samples t-tests were used to compare differences in demographic characteristics, behavioral characteristics, and executive function performance between the experimental and control groups at baseline. Secondly, 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze the differences between the two groups of subjects before and after the executive function experiment Intergroup factor was group (experimental group, control group), and intragroup factor was time (pre-test, post-test), and for the indicators with significant main and interaction effects that appeared during the statistical process, further pairwise comparisons were conducted for the simple effects analysis, and the effect sizes were expressed as partial η2. The significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Analysis of variability at baseline

According to Table 2, there were no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) between the experimental group and the control group in demographic characteristics, behavioral statistics, or baseline test metrics such as Time to First Fixation (TFF), Fixation Count (FC), Total Visit Duration (TVD), Total Fixation Duration (TFD), Visit Count (VC), and the ratio of correct to incorrect for first response, indicating that the experimental conditions were met.

Differential analysis of RJA eye movement characteristics before and after intervention

This study examined the impact of temporal, group and interaction variables on six test indicators (TFF, FC, TFD, TVD, VC and the ratio of correct to incorrect for first response) using repeated measures of analysis of variance. The results of the analysis demonstrated that the time effect, group effect, and interaction effect exhibited varying degrees of significance for different indicators (see Table 3).

The analysis of the time effect demonstrated no statistically significant changes in the two indicators, TVD and FC (TVD: P = 0.557, FC: P = 0.206). This indicates that there is no significant difference between the pre-test and the post-test over time for these indicators, suggesting that the time factor may not have had a significant impact on changes in these indicators. The time effects of the four indicators (TFF, TFD, VC, and Ratio) were all significant (TFF: P = 0.014, TFD: P = 0.029, VC: P = 0.011, Ratio: P = 0.000). In particular, the time effect is highly significant for the proportion indicator, indicating that the test values have changed significantly over time among these three indicators.

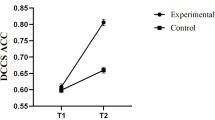

The results of the analysis of group-to-group effects indicate that there are significant differences in the performance of the experimental group and the control group on the FC (P = 0.003) and Ratio (P = 0.009) indicators. The experimental group demonstrated superior performance at the post-test compared to the control group. No significant differences were observed in the group-to-group effects of the remaining indicators. The interaction effects of all indicators were significant (TFF: P = 0.001, FC: P = 0.000, TFD: P = 0.001, TVD: The results indicate that the interaction between time and group has a significant effect on the change of each indicator (P = 0.012, VC: P = 0.001, Ratio: P = 0.001), as indicated by the partial η2 (TFF: 0.709, FC: 0.784, TFD: 0.707, TVD: 0.256, VC: 0.663, Ratio: 0.425). In particular, significant discrepancies were observed in the evolution of performance between the experimental and control groups at various time points, suggesting that the degree of enhancement following the intervention differed considerably between the two groups. A further simple effect analysis demonstrated that all indicators in the experimental group exhibited a statistically significant effect in comparison to the control group (P < 0.05). To further validate the robustness and interpretability of the statistical results of this study, we conducted a post-hoc power analysis for the “time × group” interaction effects of each indicator. The analysis was based on the partial eta squared (Partial Eta Squared) values output by SPSS. These values were first converted to effect sizes (Cohen’s f), and then combined with the experimental design of this study (two-factor mixed design, two levels of within-group variables, two levels of between-group variables, total sample size n≈24, α = 0.05) to estimate the statistical power corresponding to each interaction effect.

The analysis results indicate that the power for the majority of interaction effects exceeds 0.95, reaching or approaching optimal statistical power (Power = 1.000), suggesting that the intervention’s impact on the corresponding indicators is not only statistically significant but also highly reliable in terms of stability and reproducibility.The trends in RJA eye-tracking data changes for the two groups before and after the intervention are shown in Fig. 4.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that the intervention model of sports-arts integration can effectively enhance the RJA performance of children with ASD. This was evidenced by the interaction effect of the six gaze-type indices of eye movement characteristics of children with ASD, namely, TFF, FC, TFD, TVD, VC, and the ratio of correct and incorrect for the first response, as well as their significant effects. Prior research has demonstrated that children with ASD exhibit notable enhancements in visual attention, joint attention, and attention to peers following group motor skill learning19. This finding is consistent with the results of the present study, which demonstrates the efficacy of physical exercise in improving the RJA level in children with ASD. In addition, several scholars have validated the effectiveness of drawing art and other behavioral intervention models in enhancing the attention level of children with ADHD and ASD20.

RJA represents a pivotal mechanism for social life adaptation and a significant cognitive and developmental milestone during the early years of a child’s life21. However, the development of RJA in children with ASD tends to lag behind that of their typically developing counterparts. In this study, we devised a sports-arts integration intervention program, combining basketball and painting art in a natural and seamless manner. The classroom environment was designed to facilitate multisensory stimulation and dynamic interaction, with a curriculum that incorporated multidimensional training content. In the integration intervention, children with ASD were instructed to combine vision and movement and simultaneously to plan, inhibit, and respond flexibly to external stimuli. This was achieved through the implementation of dynamic multi-player passing activities and inspirational creations,RJA improvements may relate to prefrontal cortex function, though neural data (e.g., fMRI) are needed to confirm this. Non-significant time effects for TVD and FC (P > 0.05) suggest these metrics may be less sensitive to the intervention duration22. Studies have demonstrated that the enhancement of Joint Attention behaviors in children with ASD is associated with social interaction tasks. The activation of neural networks during intervention has been demonstrated to improve social deficits in children with ASD23. In this study, a number of interactive sessions, including but not limited to verbal encouragement from the instructor and the drawing teacher, verbal instruction, and an exchange of drawings at the end of the session, activated the superior prefrontal gyrus, and the posterior cingulate gyrus was also activated, which corresponded with an improvement in the ability of children with ASD to interpret others’ awareness and social reasoning24. Research has shown that the sports-arts intervention model, which integrates audio-visual and motor stimuli, enhances the synergy between the sensory cortex, parietal lobe, and cerebellum. This makes it easier for children with ASD to understand and respond to complicated things. The results of research have demonstrated that multisensory training improves attention allocation and sensory sensitivity in children with ASD25.

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) suggests that the combination of intrinsic motivation and external contexts can significantly increase participants’ motivation26. And social learning theory suggests that positive reinforcement of interactive behavior accelerates children’s skill acquisition27. The competitive and creative painting activities established during the physical-artistic integration intervention were competitive and highly engaging, which not only reduced the resistance of children with ASD to the tasks in traditional interventions but also stimulated their intrinsic motivation to maintain a higher level of attention in completing the training tasks. Generally, successful completion of basketball and drawing tasks requires collaboration. Interactions with coaches or other children may provide timely social feedback, thereby enhancing children with ASD’s attention to and engagement with the behavior of others. This may be directly responsible for the improvement in RJA eye movement characteristics observed in the present study.

It has been demonstrated that long-term physical activity interventions can markedly enhance neurotransmitter levels in children with ASD28. Sports and arts activities have been shown to promote the production of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, hormones whose optimal regulation contributes to mood stabilization and anxiety relief29,30. Our findings align with evidence that physical exercise enhances attentional control in ASD, further amplified here by integrating arts-based cues.The physical activity inherent to sports and arts can facilitate the production of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Furthermore, moderate-intensity basketball has been demonstrated to significantly elevate levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which serves as a crucial biochemical foundation for neural remodeling in the brain. This, in turn, contributes to structural remodeling of the brain and enhancement of neural connectivity31. A 12-week mini-basketball intervention for children with ASD demonstrated a notable enhancement in white matter connectivity within brain regions, accompanied by a concomitant improvement in socialization and executive function32. The present study utilized the RJA eye-tracking program to optimize neural connectivity within the brain. The improvement of RJA eye movement characteristics in the present study may also be associated with the reconditioning of neural functions.

Limitations and perspectives

Due to the objective limitations of the resources available for this study, the sample size was relatively small. This may impact the generalizability of the experimental results. Despite using eye-tracking technology to objectively evaluate RJA performance, the experiment presented relatively homogeneous stimulus materials and generally structured task types. In contrast, a variety of complex stimulus conditions were simultaneously available in a more naturalistic setting. Secondly, it is challenging to examine the alterations in RJA conduct solely through an investigation of behavioral traits. Additionally, determining the impact of the integration intervention on the neural processing of social information in children with ASD is challenging, and the combination of physical and artistic interventions requires a significant level of involvement from ASD families.Further studies should continue to refine the integration protocol, develop interventions that reduce participation costs and save ASD families’ energy.Expand the sample size or employ multi-center sampling, and utilize neuroscience techniques (e.g., MRI, EEG, etc.) to elucidate the underlying causes of the observed abnormalities in RJA performance in children with ASD. This will enhance the statistical efficacy and facilitate the investigation of the physiological mechanisms underlying social deficits in children with ASD.

Conclusion

This intervention improves RJA eye-movement characteristics, though small sample size limits generalizability. Future research should expand samples and investigate neural mechanisms using neuroimaging.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Hou, Y. J. & Yan, T. R. The effects of parenting perfectionism on problem behaviors in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorder: The chain-mediated role of parenting burnout and psychological control. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 7, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2024.07.005 (2024).

Denis, F. et al. Early detection of 5 neurodevelopmental disorders of children and prevention of postnatal depression with a mobile health app: observational cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 10, e58565 (2024).

Mundy, P. & Newell, L. Attention, joint attention, and social cognition. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16(5), 269–274 (2007).

Han, X. L. et al. Characteristics of response to joint attention under diverse guiding behaviors in preschoolers with moderate to severe autism spectrum disorder. Chin. J. Rehabil. Theory Practice 30(8), 882–887. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9771.2024.08.002 (2024).

Franchini, M., Armstrong, V. L., Schaer, M. & Smith, I. M. Initiation of joint attention and related visual attention processes in infants with autism spectrum disorder: Literature review. Child Neuropsychol. 25(3), 287–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2018.1490706 (2018).

Hampton, L. H., Kaiser, A. P. & Fuller, E. A. Multi-component communication intervention for children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Autism 24(8), 2104–2116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320934558 (2020).

Landa, R. J. Efficacy of early interventions for infants and young children with, and at risk for, autism spectrum disorders. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 30(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1432574 (2018).

Fitriyaningsih, A., Dewi, Y. L. R. & Adriani, R. B. Meta-analysis the effect of sensory integration therapy on sensoric and motoric development in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Mater. Child Health 7(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.26911/thejmch.2022.07.01.06 (2021).

Nezhad, T. M. et al. Implementation of an integrated pharmacy education system for pharmacy students: A controlled educational trial. BMC Med. Educ. 24(1), 1272–1272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06277-2 (2024).

Wang, J.-G. et al. Effects of mini-basketball training program on executive functions and core symptoms among preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Sci. 10(5), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050263 (2020).

Liu, G. et al. Effects of Parent-Child Sandplay Therapy for preschool children with autism spectrum disorder and their mothers: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatric Nurs. 71, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2023.02.006 (2023).

Chen, A. G. Educational neuroscience: The innovation of physical education 138–177 (Educational Science Publishing House, 2016).

Dong, X. X. et al. Effects of mini-basketball training on repetitive behaviors and gray matter volume in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. China Sport Sci. Technol. 56(11), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.16470/j.csst.2020126 (2020).

Harris, H. K., Sideridis, G. D., Barbaresi, W. J. & Harstad, E. Male and female toddlers with DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder have similar developmental profiles and core autism symptoms. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 54(3), 955–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05874-8 (2024).

Nystrm, P. et al. Joint attention in infancy and the emergence of autism. Biol. Psychiat. 86(8), 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.006 (2019).

Zhang, Y. R., Peng, S. & Shao, Z. A study on the characteristics of responsive joint attention under the guidance of different types of cues in children with autism spectrum disorders. Chin. J. Nervous Ment. Dis. 48(5), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0152.2022.05.003 (2022).

Kang, J. N., Han, X. Y., Geng, X. L. & Li, X. L. Research on the abnormal facial processing recognition of children with autism spectrum disorder based on eye-tracking technology. Chin. J. Rehabil. Med. 37(7), 933–936. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2022.07.012 (2022).

Schopler, E. et al. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 10(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02408436 (1980).

Ge, L. K. et al. Sharing our world: Impact of group motor skill learning on joint attention in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06528-7 (2024).

Lu, X. P., Chen, Q. P. & Ming, L. Assessment of effects on mandala art therapy for children with autism. Chin. J. Sch. Health 38(8), 1179–1182. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2017.08.018 (2017).

Khalulyan, A., Byrd, K., Tarbox, J., Little, A. & Moll, H. The role of eye contact in young children’s judgments of others’ visibility: A comparison of preschoolers with and without autism spectrum disorder. J. Commun. Disord. 89, 106075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.106075 (2021).

Khalki, H. et al. Early movement restriction impairs the development of sensorimotor integration, motor skills and memory in rats: Towards a preclinical model of developmental coordination disorder?. Eur. J. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.16594 (2024).

Carati, E., Angotti, M., Pignataro, V., Grossi, E. & Parmeggiani, A. Exploring sensory alterations and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder from the perspective of artificial neural networks. Res. Dev. Disabil. 155, 104881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2024.104881 (2024).

Khalil, R., Tindle, R., Boraud, T., Moustafa, A. A. & Karim, A. A. Social decision making in autism: on the impact of mirror neurons, motor control, and imitative behaviors. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 24(8), 669–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13001 (2018).

De Domenico, C. et al. Exploring the usefulness of a multi-sensory environment on sensory Behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Clin. Med. 13(14), 4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144162 (2024).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68 (2000).

Akers, R.L., & Jennings, W.G. (2015). Social learning theory. In The Handbook of Criminological Theory, Piquero, A.R. (Ed.). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118512449.ch12

Ren, J. & Xiao, H. Exercise for mental well-being: exploring neurobiological advances and intervention effects in depression. Life 13(7), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13071505 (2023).

Chen, J., Zhou, D., Gong, D., Wu, S. & Chen, W. A study on the impact of systematic desensitization training on competitive anxiety among Latin dance athletes. Front. Psychol. 15, 1371501. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1371501 (2024).

Sun, H. Z., Wang, G. X., Qiu, Z. Y., Yang, T. & Yin, R. B. Application of ICF-CY in analysis of functioning and disability, and physical activity and sport rehabilitation for children with autism spectrum disorder. Chin. J. Rehabil. Theory Pract. 23(10), 1123–1129. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9771.2017.10.002 (2017).

de Oliveira, L. R. S. et al. An overview of the molecular and physiological antidepressant mechanisms of physical exercise in animal models of depression. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49, 4965–4975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-07156-z (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Effects of exercise intervention on executive function and default network functional connectivity in children with autism associated with mental retardation. J. Cap. Univ. Phys. Educ. Sports 35(5), 493–502 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial supports Anhui Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Foundation.(AHSKQ2023D081). Meanwhile, thanks for Jia-Qi Du’s help in this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Anhui Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Foundation.(AHSKQ2023D081).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qifan WU: Writing,data analysis,intervention coachWeimin Cai: editing,checking,funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Ethics committee of anhui normal university, grant numberAHNU-ET2024178.Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants.

Informed consent

to publish.

Informed consent

was obtained from the participant to publish the information/image(s) in an online open-access publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, QF., Cai, WM. The effects of an integrated sports and arts intervention on response joint attention (RJA) eye-movement characteristics in children with mild autism. Sci Rep 15, 31925 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16970-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16970-x