Abstract

This research examines the scattering of elastic waves and the phenomenon of dynamic stress concentration in piezoelectric smart building materials and structures containing holes of arbitrary shapes. It is grounded in the principles of elastic dynamics theory. The analysis leverages Liu’s complex variable function and conformal mapping methods to scrutinize the dynamic stress distribution in proximity to a solitary elliptical hole and a pair of circular holes. The study delves into the influence of various factors, including the incident wave number, elliptical eccentricity, and hole spacing, on the dynamic stress concentration factor. The findings reveal that, although the dynamic stress concentration factor exhibits predictable patterns as the wave number fluctuates, it remains highly susceptible to changes in these parameters, demonstrating symmetrical yet irregular variations. This research is crucial for addressing the challenges posed by holes and defects in piezoelectric materials during engineering design and service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the 1970s and 1980s, with the emergence of smart materials research, people began to consider using the properties of piezoelectric materials1 to provide self-sensing or self-regulation for buildings, such as piezoelectric ceramics (e.g. PZT, lead zirconate titanate) and piezoelectric composites have gradually been introduced into structural health monitoring2. Compared with traditional building materials cement; sand3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12; concrete, piezoelectric smart building materials 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 can reduce carbon emissions both in the manufacturing and use process, use natural energy, such as vibration, wind power for power generation, it can also monitor the state of the building in real time, improve safety and service life, in terms of economic benefits of lower costs, and extend the service life of building materials.

However, piezoelectric materials inevitably have holes in them during the manufacturing process, and sometimes holes are created in the material to meet certain process requirements. These structural defects or man-made holes can cause geometrical discontinuities in the flat structure, and stress concentration near the defects or holes, Whereas the concept of stress concentration near defects or holes was first introduced by Peterson 22, can greatly reduce the load-bearing capacity of piezoelectric material structures as well as reduce the service life of the structures. Therefore, the study of piezoelectric material structures as well as reduce the service life of the structures. Therefore, the study of static and dynamic stress concentration in piezoelectric materials with defects or holes is of great value for engineering applications.

During the study, Yang23 et al derived linear equations to ascertain the undetermined parameters by employing the method of surface tension analysis, producing approximate values for the parameters with a limited series expansion. Wu24 et al. developed a bio-inspired bistable piezoelectric structure for low-frequency energy harvesting. The design improves energy conversion efficiency and reduces stress concentration, verified through modeling, simulations, and experiments, highlighting its potential for vibration-based energy systems. Wang25 et al. investigated the interaction of SH waves with non-circular hole piezoelectric materials using the complex function approach and found that the shape of non-circular holes has a significant effect on stress concentration, and that a deviation from the circular shape increases the dynamic stress concentration factor. Li26 et al. combined the elastic wave theory with the complex function of variations to analyse the wave scattering and interference effects in double-hole piezoelectric materials and found that the hole spacing affects the wave field distribution, and the double holes trigger higher dynamic stress concentration and change the electro-elastic coupling behaviour. Qi27 and colleagues conducted a dynamic analysis of piezoelectric materials containing an elliptical hole subjected to shear horizontal waves. Using analytical and numerical methods, they derived solutions for stress and electric displacement fields around the hole. Their study revealed the influence of wave frequency, hole geometry, and material properties on the dynamic response, providing insights into the design of piezoelectric devices under dynamic loading conditions. An28 and co-authors investigated the dynamic performance of piezoelectric bi-materials with an interfacial crack near an eccentric elliptical hole under anti-plane shear loading. By applying complex function theory and numerical techniques, they obtained solutions describing the stress intensity factors and electric displacement fields. Their findings demonstrated how the relative positions of the crack and hole, as well as material properties, affect the mechanical and electrical behavior of the bi-material system, offering guidance for the reliability analysis of piezoelectric composites. Wang29 et al. analysed the influence of the detail structure on the electromechanical response of the energy harvesting device by establishing a finite element model and found suitable structural parameters to avoid edge stress concentration. Qi30 employed complex variable methods and Fourier series expansion to analyze the dynamic stress distribution in an infinite piezoelectric material strip containing a circular cavity. By applying boundary conditions specific to piezoelectric materials, they derived analytical solutions for the coupled mechanical and electrical fields around the cavity. Numerical simulations were used to validate the theoretical models and visualize the effects of different parameters. Their results showed that the dynamic stress distribution is significantly influenced by the cavity’s presence, with pronounced stress concentrations under specific frequency conditions. Li31 investigated the interaction between a screw dislocation and an elliptical hole with two asymmetrical cracks in a one-dimensional hexagonal quasicrystal with piezoelectric effects. They utilized the complex potential function method and conformal mapping techniques to derive analytical solutions for the stress and electric fields in this complex system. Their findings demonstrated the intricate coupling between mechanical and electrical fields, influenced by the geometry of the hole, cracks, and the dislocation position. Zhou32 et al. analyzed the static/dynamic response of imperfectly bonded orthotropic piezoelectric laminates in cylindrical bending using a semi-analytical SS-DQM approach with a spring-layer interface model. They quantified the effects of interfacial imperfections, boundary conditions, and lay-up schemes on electromechanical behavior, validating the method’s accuracy for complex laminates. Zhou33 et al. utilized the reverberation-ray matrix method (MRRM) to analyze laminated piezoelectric cylindrical shells. Their work established a rigorous framework based on Donnell shell theory and first-order differential equations. Crucially, MRRM inherently ensured numerical stability (even with repeated eigenvalues), enabling robust high-frequency vibration modeling and transient wave propagation analysis under impact loading. Zhou34 et al derived dual and coupling relations by employing the reverberation-ray matrix method, establishing a mathematically rigorous framework through first-order differential equation analysis and addressing repeated eigenvalue cases to ensure numerical stability in high-frequency vibration modeling of piezoelectric laminates.

This paper delves into the study of elastic wave scattering and dynamic stress concentration in piezoelectric materials and structures containing arbitrary holes, utilizing Liu’s complex function approach and conformal mapping method. It presents analytical solutions to the pertinent problems. This paper presents numerical results of dynamic stress distribution around perforations for a single elliptic and two circular perforations.

Results

This paper examines the elastic scattering and stress concentration in piezoelectric intelligent building materials and structures based on elastic mechanics theory, utilizing the complex variable function of Liu and the conformal mapping method. The findings are as follows

-

(1)

When m is constant, the dynamic stress concentration coefficient’s image exhibits irregular but symmetrical changes. The extreme value of this coefficient varies with the continuous increase of the wave number ka.

-

(2)

The maximum dynamic stress concentration coefficient also varies with ka in a specific pattern under different parameters \(\lambda\), provided that m remains constant. The coefficient reaches its maximum value at \(ka = 0.2 < 0.5\). Generally, as ka increases, the dynamic stress concentration coefficient tends to decrease and fluctuate.

-

(3)

Relative to m = 1/9, the variation of the dynamic stress concentration factor is more drastic and irregular at m = 1/6. Not only that, the dynamic stress concentration factor is larger and the dynamic stress concentration is more pronounced.

:

Basic theory of piezoelectric smart building materials

-

1.

Piezoelectric effect

The piezoelectric effect was first discovered by brothers Pierre and Jacques Curie in 1880. They discovered that certain crystalline materials polarise when subjected to a mechanical force, producing a voltage, a phenomenon known as the positive piezoelectric effect. Conversely, when an electric field is applied to these materials, they elongate or shorten depending on the polarity of the field, a phenomenon known as the inverse piezoelectric effect. Together, these two effects constitute electro-mechanical coupling.

-

2.

Basic characterisation of the piezoelectric effect

The piezoelectric effect consists of the positive and the inverse piezoelectric effect, which together constitute the fundamental properties of piezoelectric materials. The positive piezoelectric effect describes the fact that when a crystalline material with an asymmetric centre is subjected to a mechanical stress, it produces an electrodeposition within the material and generates an equal number of bound charges of opposite sign on its two opposite surfaces. The generation of this charge is proportional to the magnitude of the external force and the material returns to an uncharged state when the external force is removed. The positive piezoelectric effect has a wide range of applications in sensor technology, e.g. for detecting changes in pressure, acceleration and force and converting these mechanical quantities into electrical signals.

The inverse piezoelectric effect, on the other hand, refers to the fact that when an electric field is applied in the direction of polarisation of a dielectric, the dielectric undergoes deformation and the amount of deformation is proportional to the strength of the external electric field. When the electric field is removed, the deformation of the dielectric disappears. The inverse piezoelectric effect has important applications in ultrasound engineering and micromotion, such as the manufacture of ultrasound transducers that convert electrical energy into mechanical vibration for use in areas such as medical imaging, cleaning and welding.

-

3.

Stress concentration and acoustic propagation properties in dynamic environments

It has already been described that stress concentrations under static loading can lead directly to structural damage, but stress concentrations are important for the design of highly sensitive sensors35,36. By introducing a specific structural design into a piezoelectric material, it is possible to concentrate stress in certain areas, thus improving the sensor’s ability to respond to small changes. For example, by locally gouging or changing the geometry of the material, higher stress levels can be generated near the patch site, which in turn increases the sensitivity of the sensor. This design approach can be used to detect subtle cracks or fatigue damage in structures, which are often accompanied by abnormal concentrations of localised stress. In addition to this, the propagation of acoustic37 waves should not be neglected. The propagation of acoustic waves in piezoelectric materials generates an electric field due to the piezoelectric effect, which manifests itself as acoustic-electrical signal coupling. This coupling effect is the basis for the application of piezoelectric materials in ultrasonic engineering and acoustic transducers. The frequency and wavelength of the incident acoustic wave determine the coupling efficiency, due to the fact that acoustic waves of different frequencies and wavelengths have different propagation properties in the material, which affects the interaction between the acoustic wave and the electric field. In turn, the propagation behaviour of acoustic waves is influenced by the elastic constants, dielectric constants and boundary conditions of the piezoelectric material. The elastic constant determines how well the material responds to stress, while the dielectric constant affects the generation and propagation of the electric field. Boundary conditions, such as the geometry of the material and the external environment, also have an effect on the propagation path and coupling efficiency of acoustic waves. For example, the propagation characteristics of surface acoustic waves (SAWs) are affected by the thickness of the piezoelectric film layer, with different thicknesses leading to different phase velocities and dispersion characteristics.

Wave equation and its solution

In piezoelectric materials, the fundamental equation governing the steady-state anti-plane dynamics problem is

where, \(\tau_{xz}\) and \(\tau_{yz}\) are the elements of shear stress.\(D_{x}\) and \(D_{y}\) are the components of electric displacement.\(\rho\) is the density of the mass. The fundamental relationship governing the behavior of piezoelectric materials can be expressed as:

where,\(c_{44}\) r epresents the elastic modulus of the piezoelectric material.;\(e_{15}\) is the piezoelectric coefficient of the piezoelectric materials.\(\kappa_{11}\) is the permittivity of the piezoelectric material.;\(\phi\) is the electric potential in a medium.

Without loss of generality, the steady-state solution of the problem is studied

where,\(\omega\) is the circular frequency of the vibration;\({\text{i}}\) is an imaginary unit.

The time factor and the symbols ~ on the generalized displacement function are omitted. Substituting the constitutive relation (2) into the governing equation (1), an equation of the following form can be obtained

It should be pointed out that the governing Eq. (1) of displacement and potential need to be decoupled here, and a new function \(\varphi (x,y)\) is introduced.

Then an equation of the following form can be obtained:

where: k is the wave number,\(c^{ * } = c_{44} + \frac{{e_{15}^{2} }}{{\kappa_{11} }}\) and \(k^{2} = \frac{{\rho \omega^{2} }}{{c^{ * } }}\).

The potential can be determined by the following formula:

Complex variables \(\zeta = x + {\text{i}}y,\overline{\zeta } = x - {\text{i}}y\) are introduced into the generalized internal forces of piezoelectric materials, which are obtained by substitution and finishing.

There are the following transformation relationships

In a rectangular coordinate system, the governing equation (1) can be written in the following form

The constitutive relation (2) is

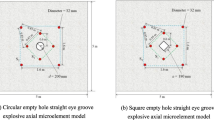

The outer domain (inner domain) of the non-circular open boundary L on the \(z\) plane can be mapped to the outer domain (inner domain) of the unit circle (inner domain) of the boundary \(S\) on the \(\eta\) plane by conformal mapping technique for addressing the issues of curved wave scattering and dynamic stress concentration in a plate containing arbitrary holes. Figure 1 visualises this transformation process,The mapping function can take the following form

where, \(\psi (\eta )\) is a holomorphic function.

Formula,\({\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\lambda }} = \frac{\eta }{\rho }\frac{{\Omega^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)}}{{\left| {\Omega^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right|}}\).

Incidence and total electroelastic wave field of electric sound wave

Considering an infinite piezoelectric material with arbitrary holes, where a steady SH electro-acoustic wave is incident along the x-axis, the corresponding outgoing plane displacement field can be described as \(w^{\left( i \right)}\) and in-plane potential field \(\phi^{\left( i \right)}\) can be formulated as the scattering wave field generated by the hole as a scatterer can be expressed as

Then, the combined field within the piezoelectric material containing circular holes can be expressed as

Namely

Within a circular hole, there is no elastic displacement field present; however, only the electric potential field exists \(\phi^{c}\), And since the charge density within the hole is zero, the solution must satisfy the Laplace equation. \(\nabla^{2} \varphi^{c} = 0\). Given that the electric potential within a circular hole cannot be infinite but must be finite, its expression can be formulated as follows:

The corresponding stress can then be expressed as:

where, \(\lambda = \frac{{e_{15}^{2} }}{{c_{44} \kappa_{11} }}\) represents the dimensionless piezoelectric constant, while \(\kappa_{0}\) denotes the dielectric constant in vacuum.

Boundary conditions and mode coefficients are considered in the context of arbitrary-shaped holes

A piezoelectric medium containing a single, arbitrary-shaped hole is investigated.. On the \(\eta\) plane, Assuming the open hole represents a free boundary condition, three boundary conditions can be specified

Equation (15) and Eq. (16) are substituted into Eq. (20) of the open boundary condition, and based on the orthogonality of the function system, the mode coefficient to be found can be obtained \(A_{n} ,B_{n} ,C_{n}\).

Among them \(\varepsilon_{n} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} 1,\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} n = 0 \hfill \\ 2,\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} n \ne 0 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.\)

Dynamic stress concentration coefficient

The dynamic stress concentration is characterized by the opening hole, where the dynamic stress concentration coefficient is defined as the ratio of the annular dynamic stress surrounding the hole to the amplitude of the incident wave’s annular stress in the direction of incidence.

Validation of results

In this section, the obtained results will be compared with the research results of elliptical holes in elastic media. Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of the dynamic stress concentration factors (DSCF) under different wave numbers, hole shapes, and surface effects. The comparison results indicate that the relative error in the dynamic stress concentration factors of the two is less than 5% at different wavenumbers, confirming the accuracy of calculation method.

Numerical examples

Given a steady-state wave \(w_{{}}^{(i)}\) incident along the x-axis, the mapping function for a circular hole with radius a can be

For a piezoelectric material containing an elliptical hole with long and short semi-axes a and b, the mapping function is

where,\(r_{0} = (a + b)/2\), \(m = \left( {a - b} \right)/\left( {a + b} \right)\).

Based on the formula of elastic wave scattering and dynamic stress concentration in piezoelectric materials with a single arbitrary hole, the corresponding calculation program is formulated with the elliptic hole as an example. The Poisson ratio is \(\nu = 0.3\) and the dimensionless wave number is \(ka = 0.1\sim 5.0\) with \(n = 15\).

Figure 2 describes the distribution of dynamic stress concentration coefficients of different wave numbers and parameters \(\lambda\) along the edge of the elliptical hole \((a/b = 5/4)\), respectively. Figure 3 shows the curve of the dynamic stress concentration coefficient of the elliptic hole \((a/b = 5/4)\) with the dimensionless wave number \(ka\) obtained by analysis and calculation.

Figure 4 describes the distribution of dynamic stress concentration coefficients of different wave numbers and parameters \(\lambda\) along the edge of the elliptical hole \((a/b = 7/5),\) respectively. Figure 5 shows the curve of dynamic stress concentration coefficient with dimensionless wavenumber ka for the elliptical hole \((a/b = 7/5)\) obtained by analysis and calculation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the experimentation of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, J. et al. Piezoelectric materials for sustainable building structures: Fundamentals and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 101, 14–25 (2019).

Ju, M. et al. Piezoelectric materials and sensors for structural health monitoring: fundamental aspects, current status, and future perspectives. Sensors 23(1), 543 (2023).

Nidheesh, P. V. & Suresh-Kumar, M. An overview of environmental sustainability in cement and steel production. J. Clean. Prod. 231, 856–871 (2019).

Afroughsabet, V. et al. Investigation of the mechanical and durability properties of sustainable high performance concrete based on calcium sulfoaluminate cement. J. Build. Eng. 43, 102656 (2021).

Dabbaghi, F. et al. Life cycle assessment multi-objective optimization and deep belief network model for sustainable lightweight aggregate concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 318, 128554 (2021).

Hamidi, F., Aslani, F. & Valizadeh, A. Compressive and tensile strength fracture models for heavyweight geopolymer concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 231, 107023 (2020).

Afshar, A. et al. Corrosion resistance evaluation of rebars with various primers and coatings in concrete modified with different additives. Constr. Build. Mater. 262, 120034 (2020).

Scrivener, K. L., John, V. M. & Gartner, E. M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 2–26 (2018).

Gerges, N. et al. Eco-friendly mortar: optimum combination of wood ash, crumb rubber, and fine crushed glass. Case Stud Constr Mater 15, 100588 (2021).

He, Z. et al. A novel development of green UHPC containing waste concrete powder derived from construction and demolition waste. Powder Technol. 398, 117075 (2022).

Shi, J. et al. Experimental study on full-volume slag alkali-activated mortars: Air-cooled blast furnace slag versus machine-made sand as fine aggregates. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 123983 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. Preparation and characterization of lightweight aggregate foamed geopolymer concretes aerated using hydrogen peroxide. Constr. Build. Mater. 256, 119442 (2020).

Habib, M., Lantgios, I. & Hornbostel, K. A review of ceramic, polymer and composite piezoelectric materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 55(42), 423002 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Additive manufacturing of piezoelectric materials. Adv. Func. Mater. 30(52), 2005141 (2020).

Safaei, M., Sodano, H. A. & Anton, S. R. A review of energy harvesting using piezoelectric materials: state-of-the-art a decade later (2008–2018). Smart Mater. Struct. 28(11), 113001 (2019).

Guerin, S., Tofail, S. A. & Thompson, D. Organic piezoelectric materials: milestones and potential. NPG Asia Materials 11(1), 10 (2019).

Liang, Z. et al. Piezoelectric materials for catalytic/photocatalytic removal of pollutants: Recent advances and outlook. Appl. Catal. B 241, 256–269 (2019).

Aabid, A, et al. "A review of piezoelectric material-based structural control and health monitoring techniques for engineering structures: Challenges and opportunities. Actuators Vol. 10, No. 5. MDPI 2021.

Yan, X. et al. Recent progress on piezoelectric materials for renewable energy conversion. Nano Energy 77, 105180 (2020).

Aydin, A. C. & Çelebi̇ O,. Piezoelectric materials in civil engineering applications: A review. ACS Omega 8(22), 19168–19193 (2023).

Gomasa, R. et al. A review on health monitoring of concrete structures using embedded piezoelectric sensor. Constr. Build. Mater. 405, 133179 (2023).

Pilkey, Walter D., Deborah F. Pilkey, and Zhuming Bi. Peterson’s stress concentration factors. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

Yang, G., et al. Surface tension-induced stress concentration around an elliptical hole in piezoelectric material. (2019).

Wu, N., Jiyang, Fu. & Xiong, C. A bio-inspired bistable piezoelectric structure for low-frequency energy harvesting applied to reduce stress concentration. Micromachines 14(5), 909 (2023).

Wang, X. L., Yang, X. J. & Zhang, R. Dynamic stress concentration in a piezoelectric material with a non-circular hole subjected to an SH-wave. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 61, 661–668 (2020).

Li, Z., Liu, H. & Zhen, W. Elastic wave scattering and dynamic stress concentrations around double holes in piezoelectric media. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 8(12), 3060 (2020).

Qi, H. et al. Dynamic analysis of piezoelectric materials with an elliptical hole under the action of shear horizontal waves. Mech. Mater. 169, 104323 (2022).

An, N., Song, T. & Hou, G. Dynamic performance for piezoelectric bi-materials with an interfacial crack near an eccentric elliptical hole under anti-plane shearing. Math Mech Solids 27(1), 93–107 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. "Structure simulation optimization and test verification of piezoelectric energy harvester device for road. Sensors Actuat A Phys 315, 112322 (2020).

Qi, H., Xang, M. & Guo, J. The dynamic stress analysis of an infinite piezoelectric material strip with a circular cavity. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 28(17), 1818–1826 (2021).

Li, L., Cui, X. & Guo, J. Interaction between a screw dislocation and an elliptical hole with two asymmetrical cracks in a one-dimensional hexagonal quasicrystal with piezoelectric effect. Appl. Math. Mech. 41(6), 899–908 (2020).

Zhou, Y. Y., Chen, W. Q. & Lü, C. F. Semi-analytical solution for orthotropic piezoelectric laminates in cylindrical bending with interfacial imperfections. Compos. Struct. 92(4), 1009–1018 (2010).

Zhou, Y., Zhu, J. & Liu, D. Dynamic analysis of laminated piezoelectric cylindrical shells. Eng. Struct. 209, 109945 (2020).

Zhou, Y. Y. et al. Reverberation-ray matrix analysis of free vibration of piezoelectric laminates. J. Sound Vib. 326(3–5), 821–836 (2009).

Kapuria, S. & Sharma, B. N. Arockiarajan A (2019) Dynamic shear-lag model for stress transfer in piezoelectric transducer bonded to plate. AIAA J 57(5), 2123–2133 (2019).

Chorsi, M. T. et al. Piezoelectric biomaterials for sensors and actuators. Adv Mater 31(1), 1802084 (2019).

Shivashankar, P. & Gopalakrishnan, S. J. S. M. Review on the use of piezoelectric materials for active vibration, noise, and flow control. Smart Mater. Struct. 29(5), 053001 (2020).

Hu, H. et al. Scattering of SH wave by an elliptic hole: surface effect and dynamic stress concentration. Acta Mech. 234(6), 2359–2371 (2023).

Funding

This research was funded by the Key New Technology Development and Verification Service for the Transformation and Upgrading Project of Jilin Chemical Industry Group (Phase 3)grant number 2024 2202 0200 0363.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All remaining authors contributed to this article in one way or another. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, C., Zhao, Y., Yang, X. et al. Scattering and dynamic stress concentration analysis of elastic waves around arbitrarily shaped holes in piezoelectric smart building materials. Sci Rep 15, 31692 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16974-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16974-7