Abstract

In this paper, we developed a cancer dynamical system that incorporates the interaction of tumor cells, immune systems, and drug reaction systems to investigate the impact and therapeutic implications of a fractional order Caputo derivative’s with memory effects. The solutions of the proposed system are shown to be bounded and positive. The existence and uniqueness of the solutions of the suggested model are examined using a few fixed-point theorems. The global stability of the system is examined through the use of Lyapunov’s first derivative functions. For various fractional values, solutions to the fractional order system are obtained with the help of a fractional operator with a power law kernel. The kernel also checks for unique solutions and verification of the scheme through mathematical analysis using novel approaches. Next, a simulation of the derived iterative technique is made for various fractional orders against the real data at different fractional order values. This fractional order model can be used to investigate the dynamics of tumor cells, the interactions between tumor cells and immune cells, and the effects of medications on the disease. The proposed system’s controllability and observability are further addressed by using various therapies as inputs and normal cells as output. A linear control system with a closed-loop design, in which the drug is the input and treated cells are the output, is used to investigate the influence of cancer treatments on different patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cells are the fundamental component of all biological organisms. Cells divide and proliferate to produce new cells when the body needs them. Cells usually die when they get abnormally old and defective. New cells will eventually take their place. When genetic alterations interfere with this normal process, cancer arises. Uncontrollably expanding cells start to occur. Together, these cells have the ability to form a growth known as a tumor. A tumor may or may not be malignant. It is possible for a malignant tumor to grow and spread to nearby bodily parts. Although benign tumors do not spread, they can grow. According to estimates from the National Cancer Registry, cancer kills more people than TB, AIDS, and malaria put together. Statistics indicate that by 2030, there will be 13 million cancer deaths1. The degree of the illness, how the medication is administered, and the patient’s immune system’s potency are only a few of the variables that affect how a tumor reacts to therapy. The process of mathematical modeling is seen as a potentially effective approach for creating better treatment plans. Over the past few decades, many researchers have used a variety of models to approach the mathematical modeling of tumor growth and treatment. Therapeutic cancer vaccines are a promising novel adjuvant therapy that has recently been researched in the medical world. As a result, it is critical that we start creating mathematical models of cancer growth that incorporate an immune system reaction and, eventually, a reaction to vaccination treatment. In recent times, numerous experimental techniques and treatments have been identified to understand the dynamics of cancer growth in relation to immune system interaction2,3. It also illustrates how immunotherapy, one of the alternative medicines, can strengthen our immune systems and increase our capacity to fight cancer. O’Byrne et al.4 emphasize how angiogenesis contributes to the development of malignancy and the progression of disease. According to Ribas and Wolchok5, antitumor T cells activate the immune response, which is constrained by particular checkpoints. Therapies of the new generation could be able to get past these resistance mechanisms. Academics and law enforcement are working to prevent disease spread by developing treatments or vaccines for future disorders. A thorough examination of these illnesses will enable communal management and prevent further spread. The paper by Dinku et al.6 investigates how the immune system and tumor cells interact during chemotherapy. They show optimal control by presenting equilibrium points in both drug-free and treated systems, and they used Pontryagin’s maximal principle to determine the optimality system. In order to comprehend the impact of optimal control, they also contrast controlled versus uncontrolled dynamics.

Fractional calculus operations, including different functions, have been successfully derived for the purpose of mathematically modeling a range of complex issues in various fields of science and engineering, such as liquid elements, plasma material science, astronomy, picture handling, stochastic dynamical frameworks, and controlled atomic combination (e.g.,7,8). By taking memory and genetic effects into account, fractional order differential equations improve the precision and adaptability of biological systems. They enable improved prediction and control interventions by offering a sophisticated understanding of nonlinear epidemic dynamics. As a result, vaccination tactics are more effective and governments are better equipped to manage outbreaks. Using the Caputo derivative with fractional-order to reduce infertility concerns and enhance pregnancy outcomes through hormonal and IVF therapies, Yeolekar et al.9 created a nonlinear mathematical model to examine the influence of treatment on infertility. Using Banach’s fix point theorem to understand important parameters affecting infection spread and persistence, and the Caputo fractional derivative to analyze the effect of fractional orders on infection dynamics, the article10 offers two mathematical models for the dynamics of Chikungunya virus contamination. A fractional-order economic model that produces hyperchaotic attractors was presented by Jajarmi et al.11. A linear state feedback controller and an active control method for synchronization are used to manage the chaos. Özköse et al.12 used the Caputo fractional derivative to develop a fractional-order mathematical model that takes into account population dynamics among tumor, macrophage, active macrophage, and host cells. Using the least squares curve fitting approach, they investigated the parameters, requirements for solutions, and the stability of the positive steady state. They demonstrated the benefits of fractional-order modeling and used numerical simulations to comprehend the dynamic behavior of the system. With an emphasis on the impact of memory and genetic factors on infection levels, the study13 offers a novel method for comprehending the dynamics of rat bite fever transmission.

For some engineering and thermodynamical systems, Caputo and Fabrizio14 have derived another fractional derivative; this new derivation is superior to the previous Caputo derivative style. Atangana15 derives another fractional derivative to observe the potential of Fisher’s response dispersion condition. Researchers in16 used a shifted Legendre polynomial and a fractional order derivative to propose a model of the tumor-immune interaction. The model demonstrated effects on fractional-order derivatives and the proliferation rate of the Michaelis-Menten term when compared to the Adams-Bashforth scheme. Under ideal management, the model showed an increase in active immune cells and a decrease in tumor cells. The article17 proposed a straightforward solution for a Volterra integral problem using fixed point techniques in a dislocated extended b-metric space and presented a novel contraction in a huge abstract space utilizing two methods. The Caputo-Fabrizio fractional derivative operator was utilized by Yavuz and zdemir18 to define approximate-analytical solutions for linear PDEs of time-fractional order using the Laplace homotopy analysis approach. The existence and uniqueness of solutions in Banach spaces for a nonlinear differential equation involving the Caputo-Fabrizio operator were investigated by Ayseg l Keten et al.19. A mathematical model for smoking-related cancer is presented in the article20. It uses a fractional-order derivative with seven compartments. The dynamics of cancer transmission brought on by smoking are described by the ABC fractional derivative. High precision was obtained in the numerical and graphical findings by applying the Adams-Bashforth-Moulton approach. Fractional differential equations are used in another study21 to examine how smoking affects the development of cancer. The effects of immune cell strength, initial concentration sensitivity, smoking frequency, and fractional-order derivatives on tumor growth dynamics are demonstrated by the simulations. The chaotic behavior is examined for several fractional-order derivatives and is characterized by high immunological flux and smoking frequency under low beginning circumstances. Using fractional-order differential equations, Chauhan et al.22 created a mathematical technique for simulating and examining the dynamics of Listeria infections. To obtain approximate solutions and obtain important insights, the homotopy perturbation general transform method (HPGTM) was employed. In23, two distinct nonlinear regularized long wave equations are solved using a solution technique combined with an Elzaki transform, a type of integral transformation. Time-fractional partial differential equations (FPDEs) with singular and non-singular kernels are discussed in24.

According to the literature review, the best approach for studying biological systems is to use fractional-order derivatives. This article examines tumor growth dynamics within the context of fractional calculus using the integer-order model from25. The article proposes a fractional-order cancer model that captures memory effects and non-local interactions and accurately depicts how NK and CD8+ T cells interact with different tumor cell types. Compared to conventional integer-order models, fractional-order derivatives provide a more realistic depiction of the intricacies of tumor propagation and immune response progression. This method advances our knowledge of the complex dynamics of diseases by enabling more accurate forecasts and the creation of more potent control measures. By investigating tumor-immune dynamics using fractional-order derivatives, this work fills a gap in the existing literature and offers a more sophisticated understanding. It provides a forum for additional investigation into the precise mechanisms and possible ramifications for cancer treatment. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: The basic terminology of fractional derivatives is introduced in “Basic concepts” so that their theocratic background and possible applications can be understood. Using the Caputo fractional operator, we extended an existing model in “Cancer model with fractional derivative”. Section “Analysis of proposed model” covers the main evaluation of the proposed mathematical model, including stability analysis, equilibrium points, existence and uniqueness, boundedness, and positivity. Section “Computational analysis with fractional operator” presents the numerical scheme for the current model being studied. A numerical method based on Newton polynomial interpolation has been employed to discretize the problem, and the results were obtained. The simulation results are shown in “Numerical simulation”, and their implications for cancer therapy approaches are then discussed. Controllability for a linearized system is also derived in “Controllability and observability”. Section “Conclusion” discusses the study’s findings and our theocratic conclusions.

Basic concepts

Definition 2.1

26 Assume that \(\Phi\) is a continuous function on \(L^1([0,T], \mathbb {R}]\) then the Riemann-Liouville derivative of order \(\alpha \in (0,1)\) is given by

Definition 2.2

26 Consider \(\Phi\) as a continuous function on [0, T]. The derivative of Caputo can be written as

where \(n = \lfloor \alpha \rfloor + 1\) and \(\lfloor \alpha \rfloor\) represents the integer part of \(\alpha\).

When \(0<\alpha <1\) then derivative of Caputo reduces to

Cancer model with fractional derivative

Kinetics of the four populations (i.e. three types of immune cells and one of tumour cells), and two drug concentrations in bloodstream has been described in this model, using a system of ODEs from the model developed by de Pilli’s25. The populations are represented at time t by:

-

T(t): Tumour cells population;

-

N(t): NK cells population;

-

L(t): CD8+T cell population;

-

C(t): Circulating lymphocyte population (also known as white blood cells);

-

M(t): Concentration of chemotherapy drugs in the blood;

-

I(t): Concentration of immunotherapy drug in blood.

Among the many uses of fractional calculus is an issue modeling, where the Caputo fractional derivative is a key concept that yields comprehensive and precise information. An arbitrary fractional order can be utilized to explain biological systems, such the memory of tumor-immune systems. The model’s fractional version is provided by

where \(D = d \frac{(\frac{L}{T})^l}{s + (\frac{L}{T})^l} T\). The initial conditions are:

Flow chart of the dynamical system is displayed in Fig. 1.

The system above represents logistic tumor development as \(aT (1 - bT )\), tumor death produced by NK as \(-cNT\), tumor death caused by CD8+T cells as \(-DT\), and chemotherapy-driven tumor death as \(-K_T (1 - e^{-M})T\). eC represents the generation of natural killer cells from circulating lymphocytes; \(-fN\) denotes natural killer breakdown; \(-pNT\) denotes natural killer death due to tumour killing exhaustion; and \(-K_N(1 - e^{-M}))N\) represents the chemotherapy-induced NK death, while \(\frac{g T^2}{h + T^2}\) represents the NK cell recruitment. Whereas \(-qLT\) denotes CD8+T cell death from running out of tumor-killing resources, \(-mL\) represents CD8+T cell breakdown. \(r_1NT\) represents the stimulation of CD8+T cells by NK-lysed tumour cell debris, \(r_2CT\) represents the interactions between the tumor with C cells that stimulate CD8+T production, \(\frac{p_1 L I}{g_1 + I}\) IL-2 also known as interleukin-2, has a stimulatory effect on CD8+T cells. \(-K_L(1 - e^{-M})L\) is CD8+T death brought on by chemotherapy. \(-uNL^2\) represents the CD8+T cell’s quadratic death rate. \(j \frac{D^2 T^2}{k + D^2 T^2} L\) is the CD8+T cell, the controlled external Tils (tumour infiltrating lymphocytes) is \(V_L(t)\). \(-\beta C\) represents lymphocyte breakdown, \(\alpha\) denotes a steady source rate, and \(-K_C(1 - e^{-M})C\) stands for chemotherapy-induced leukaemia. Chemotherapy medication breakdown is expressed as \(-\gamma M\), and external chemotherapy controlled as \(V_M(t)\). The IL-2 breakdown is \(-\mu _I I\), external IL-2 controllable is \(V_I(t)\) and parameters values for analysis are given in Table 1.

Analysis of proposed model

Positivity of solutions

To show how the answers are positive since they represent real-world issues with idealistic goals. We examine the conditions under which the solutions of the proposed model meet the positivity criterion in this section.

Theorem 4.1

The solution of system equation T(t), N(t), L(t), C(t), M(t), I(t) are positive \(\forall\) \(t\ge 0\), if \(T(0) \ge 0\), \(N(0)\ge 0\), \(L(0)\ge 0\), \(C(0) \ge 0\), \(I(0) \ge 0\), \(I(0) \ge 0\). All solutions of the system are bounded.

Let T(t) :

Norm is defined as:

We have

In case of classical derivative, we get

For other classes we have the following inequalities:

Boundedness and positive invariant region

Theorem 4.2

For the rest of the time span, assuming nonnegative initial conditions, the system (4)’s solutions remain in the constrained positive region \({R}^{6}_{+}\).

Proof

We have

If \((T(0),N(0),L(0),C(0),M(0),I(0)) \in R_+^6\), so that the solution must be from hyperplane. The domain \(R_+^5\) is a positive invariant with non-negative orthant because the vector field is enclosed with each hyperplane. Now, we can sum up the system equations as follows:

Then we obtain

This yields

Thus, we can conclude that

is a positively invariant region. \(\square\)

Existence and uniqueness analysis

In this section, we addressed the existence and uniqueness of the suggested model using fixed-point theory. In fixed-point theory, the Schauder fixed-point theorem and Banach’s contraction mapping concept are essential. While Banach’s contraction principle provides the presence and uniqueness of a fixed point for contraction mappings on full metric spaces through iteration, Schauder’s theorem guarantees at least one fixed point for continuous self-mappings on compact convex sets in Banach spaces. The generalization of system (4) can be achieved by using a fractional derivative in the Caputo sense for \(0 < \phi \le 1\).

Considering the system as

where \(\varpi = t,T,N,L,C,M,I\).

Using initial condition and fractional integral, we have

Let

So, system (20) becomes

Now consider a Banach space \(\wp [0,\mathfrak {T}]=\mathfrak {B}\) with a norm:

Let a mapping defined as \(\diamondsuit :\mathfrak {B} \rightarrow \mathfrak {B}\)

In addition, we impose the following hypothesis on a non linear function:

P1): There exist constants \(\rho _m, \varrho _m > 0\) such that

P2): There exist a constant \(L_m > 0\) for each \(\Lambda , \bar{\Lambda } \in \mathfrak {B}\) such that

Theorem 4.3

The system (4) has at least one solution if the assumption (P1) is true.

Proof

To demonstrate that \(\diamondsuit\) is bounded, let \(\Psi = \left\{ \Lambda \in \Psi | \rho \ge \Vert \Lambda \Vert \right\}\), where

is a closed , convex subset of \(\mathfrak {B}\). Now

Since \(\Lambda \in \Psi \Rightarrow \diamondsuit (\Psi ) \subseteq \Psi\), it shows that \(\diamondsuit\) is bounded. Next, we prove that \(\diamondsuit\) is completely continuous. For this purpose, let \(t_1 < t_2 \in [0,\mathfrak {T}]\) such that

This shows that \(\Vert \diamondsuit \Lambda (t_2) - \diamondsuit \Lambda (t_1) \Vert \rightarrow 0\) as \(t_2 \rightarrow t_1\). As a result of the Arzela- Ascoli theorem, operator \(\diamondsuit\) is completely continuous. By Schauder’s fixed point theorem, the given system (4) has at least one solution. \(\square\)

Next, it is demonstrated that the system (4) had a unique solution using the Banach fixed point theorem..

Theorem 4.4

The system (4) has a unique solution if the condition (P2) is satisfied.

Proof

Let \(\bar{\Lambda }, \bar{\Lambda }_1 \in \mathfrak {B}\). We find

Hence, the \(\diamondsuit\) is a contraction. By Banach fixed point theorem, the system (4) has unique solution. \(\square\)

Equilibrium points analysis

The system given in (4) is solved for equilibrium points. We obtain

The tumor-persistence equilibrium is given as \(E^*=(T^*, N^*, L^*, C^*, M^*, I^*)\), where

Stability analysis

In this subsection, global stability is analyzed for the proposed system. To study the stability of an equilibrium point in a fractional-order system using a Lyapunov function, a suitable function must meet specific system dynamics conditions, such as the fractional derivative being negative definite or negative semi-definite, indicating stability. However, developing appropriate Lyapunov functions for fractional-order systems is difficult. We investigate the global asymptotic stability of fractional-order differential equations by presenting an elementary lemma that determines fractional derivatives of Volterra-type Lyapunov functions in the Caputo sense.

Lemma 4.1

27 Let \(h \in R^+\) represents the continuous function for which any \(t \ge t_0\),

\(J^* \in R^+\), \(\forall \phi \in (0,1)\).

First derivative of lyapunov

Lyapunov function for the endemic, \(\{T,N,L,C,M,I\}\), \(L < 0\) is the endemic equilibrium points \(E^*\).

Theorem 4.5

The endemic equilibria \(E^*\) is globally asymptotically stable, If the reproductive number \(R_0 > 1\).

Proof

Define the Volterra-type Lyapunov function as

where \(J_i, i=1,2,3,4,5,6\) are positive constants. Then putting equation (35) into main system and using Lemma (4.1) gives us

Substituting the values of the derivatives as

Replacing \(T=T-T^*\), \(N=N-N^*\), \(L=L-L^*\), \(C=C-C^*\), \(M=M-M^*\), and \(I=I-I^*\), we can have the following:

Now let \(J_1 = J_2 = J_3 = J_4 = J_5 = J_6 = 1\). We can organize the above as follows:

We can simplify the above as

where

and

It is concluded that if \(\Sigma _1 < \Sigma _2\) then \(^CD_t^\phi G < 0\); however when \(T=T^*, N=N^*, L=L^*, C=C^*, M=M^*, I=I^*\) so \(\Omega - \Sigma = 0\) , \(^CD_t^\phi G = 0\). \(\square\)

Computational analysis with fractional operator

The Caputo derivative is employed to assess the cancer-immune dynamics, and the problem is discretized numerically using Newton polynomial interpolation28. Newton polynomial interpolation is a technique that uses Newton’s divided differences to get the coefficients of an interpolating polynomial for a given collection of data points. Newton’s polynomial interpolation is used to approximate the solution within a given time interval after converting the fractional differential equation into an equivalent integral equation in order to solve a Caputo fractional model. Let

Applying fractional integral , we get

Recall the Newton Polynomial:

Replacing the Newton polynomial (50) into Eqs. (44)–(49), we have

Calculations for the integral in the Eqs. (51)–(56) are:

Hence, we get

Numerical simulation

In this section, the findings and analysis for the analytical solution of the proposed fractional equations are presented. The expressed outcomes, as mentioned in the previous section, are thought to rapidly approach the exact solution after a limited number of repetitions. For numerical simulations, we used MATLAB, selecting suitable initial conditions and parameter values from Table 1. Numerical simulations start with the following initial values: \(T(0) = 100\), \(N(0) = 10\), \(C(0) = 2\), \(L(0) = 1\), \(M(0) = 0.1\), and \(I(0) = 0.1\). Often, fractional calculus is used to describe systems with memory or long-term dependencies. We therefore experimented with a number of fractional order \(\phi\) values and contrasted the results with the integer-order scenario.

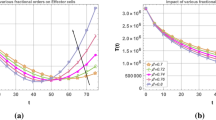

With group \(P_1\) data, the collection of graphs shown in Fig. 2 shows how the system behaves over time under various fractional orders. T(t) is compared under integer and fractional orders in the first graph (2a). In the early stages, when killer cells and other medicines are not present, tumor development happens very quickly. The tumor steadily deteriorates over time when the remaining cells in the model (4) are utilized. It is clear that T(t) shows the fastest growth rate with larger values of \(\phi\), achieving higher values in a shorter amount of time. This finding implies that fractional-order derivatives cause a delay in the growth of the tumor, which is important to consider when simulating biological systems in the real world. Figure 2b uses different fractional orders to visually show the behavior of the second compartment, which represents NK cells. The graph showed that in order to decrease and ultimately eradicate tumor cells, a large number of natural killers N(t) were required. It demonstrates how NK cells rise steadily throughout the course of various fractional orders and time periods. Figure 2c uses several fractional orders to visually show the behavior of the third compartment, which represents the CD8+T cells. In Fig. 2d, circulating lymphocytes are simulated. Both of these graphs showed that in order to decrease and ultimately eradicate tumor cells, a large number of CD8+T cells and lymphocytes are required. As the tumor gets smaller, lymphocytes stabilize. We see a rise in CD8+T cells and lymphocytes at higher fractional orders. Figure 2e displays the chemotherapeutic drug simulation at various fractional-order levels. Higher fractional orders result in a discernible rise in drug density. Because of their potential to impact tumour growth, these cells are much rarer than the others, and their usage in tumor growth regulation is gradually increasing. The immunotherapy drug’s dynamics, as depicted in Fig. 2f, increase more quickly at large \(\phi\) values than at smaller fractional orders.

The set of graphs in Fig. 3 illustrates the system’s behavior over time under various conditions using group \(P_2\) data. The total results demonstrate how crucial fractional calculus is to enhancing the mathematical depiction of the tumor-immune system. For all compartments with smaller values fractional orders, the solution curves converge to the stable state, indicating a slower approach to equilibrium because of the impact of complicated dynamics and memory on the tumor spread. The study compares integer-order results with numerical simulation results using the standard integer order model solution at \(\phi = 1\). Curves with \(\phi = 0.95, 0.90, 0.85\) show a slower increase or decline over longer time periods. Control measures can be implemented using a fair ratio. The model offers more precise predictions for long-range interactions between tumor cells and NK and CD8+T cells. Understanding the historical dynamics of cancer is necessary for effective immunological and chemotherapeutic treatments.

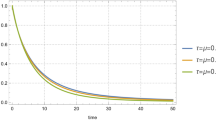

The chaotic behavior of the compartment under different initial conditions is depicted by the collection of graphs in Fig. 4. The limitations of deterministic models and the necessity of taking into account the possibility of unforeseen events are highlighted by chaotic behavior in compartment models, which has a substantial impact on comprehending and forecasting complex systems. Non-linearity and intricate interactions in systems lead to chaos, which makes long-term prediction difficult because even slight changes in the initial conditions can have a significant impact on the results over time. The Caputo fractional operator’s non-locality demonstrates how memory functions in the dynamics of the tumor-immune system. To ascertain its effectiveness, its range of low to high prevalence is examined.

Controllability and observability

The following describes a mathematically linear control system:

The dimensions of matrices A, D, and H are correct when matrices are given in J; that is, A is a matrix of \(m \times m\), D is a matrix of \(m \times p\), and H is a matrix of \(k \times mi\). For every given \(J=[t_0,t_e],t_0< t_e < \infty\) and \(J = [t_0,\infty )\), the closed interval J is defined. As \(R = [D,AD,A^2D,A^3D,...,A^{(m-1)}D]\), the controllability matrix has a size of \(m \times mp\). The system is said to be controlled due to the rank (\(rank(R)=m\)). If \(O = [H,HA,HA^2,HA^3,...,HA^{(m-1)}]^T\), then \(mk \times m\) is the observability matrix. The rank (\(rank(R)=m\)) is stated29 as the reason the system is observable. The seven examples that are associated with the different data groups are considered; in each case, the amount of cancer cell monitoring in the different body compartments is the output, and the drug dosage is the input. Drugs would be the input for case I’s group data 1, and tumor cells would be the output, with \(x = [T, N, L, C, M, I]^T\) , \(D = [0 \hspace{0.2cm} 0 \hspace{0.2cm} 0 \hspace{0.2cm} 1 \hspace{0.2cm} 1 \hspace{0.2cm} 1]^T\) and \(H = [1 \hspace{0.2cm} 1 \hspace{0.2cm} 0 \hspace{0.2cm} 0 \hspace{0.2cm} 0 \hspace{0.2cm} 0]\). \(R = [D \hspace{0.2cm} AD \hspace{0.2cm} A^2D \hspace{0.2cm} A^3D \hspace{0.2cm} A^4D \hspace{0.2cm} A^5D]\) is the controllability matrix and 5 is the rank of the controllability matrix. The observability matrix \(O = [H \hspace{0.2cm} HA \hspace{0.2cm} HA^2 \hspace{0.2cm} HA^3 \hspace{0.2cm} HA^4 \hspace{0.2cm} HA^5]\) and 1 is the rank of the observability matrix. The system is neither controllable nor observable.

Group 1 For \(E_1 = \left( 0, 0, 0, -9.477 \times 10^{-29}, 5.55556, 50000 \right)\)

Cases | Input matrix | Controllability | Observability |

|---|---|---|---|

Case I | [0 0 0 1 1 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case II | [0 0 0 0 1 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case III | [0 0 1 0 0 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case IV | [0 0 1 1 1 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case V | [0 0 0 0 0 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case VI | [0 0 0 0 1 0] | 1 | 1 |

Case VII | [0 0 0 1 0 0] | 1 | 1 |

Group 2 For \(E_2 = \left( 0, 0, 0, -1.1805539 \times 10^{-6}, 2.2222, 500000 \right)\)

Cases | Input matrix | controllability | Observability |

|---|---|---|---|

Case I | [0 0 0 1 1 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case II | [0 0 0 0 1 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case III | [0 0 1 0 0 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case IV | [0 0 1 1 1 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case V | [0 0 0 0 0 1] | 1 | 1 |

Case VI | [0 0 0 0 1 0] | 1 | 1 |

Case VII | [0 0 0 1 0 0] | 1 | 1 |

Conclusion

This paper presents a cancer dynamical system that incorporates the interaction of tumor cells, immune systems, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy drug reaction systems to investigate the impact and therapeutic implications of a fractional order Caputo derivative’s memory effect. The system’s solutions are proved to be bounded and positive, and its existence and uniqueness is examined using fixed-point theorems. A vVolterra-type Lyapunov function is used to assess the gloabl stability of equilibrium points. The Caputo fractional operator with a power law kernel is used to obtain solutions for various fractional values, and mathematical analysis is used to verify the scheme. The system is then simulated against real data using MATLAB, and its controllability and observability are further addressed by using various therapies as inputs and normal cells as output. A linear control system with a closed-loop design is used to investigate the influence of cancer treatments on different patients, showing that the system is partially controllable and observable by using different therapies. The study compared integer-order results with numerical simulations using the standard integer order model solution. Curves with \(\phi = 0.95, 0.90, 0.85\) show slower growth or decline over longer periods. The model provides more precise predictions for long-range interactions between tumor cells and NK and CD8+T cells, crucial for effective immunological and chemotherapeutic treatments. The fractional model provides a full knowledge of cancer growth throughout time, allowing for more accurate predictions of tumor responses to therapies such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy. It can optimize treatment protocols and personalize medicines by modeling time- and concentration-dependent variables. This model can help clinicians make better decisions about patient-specific treatment programs and drug administration tactics. It can also be used to investigate other diseases with spatially heterogeneous environments, such as infections and autoimmune diseases, hence opening up new possibilities for therapeutic research and optimization.

Data availability

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

References

Oke, S. I., Matadi, M. B. & Xulu, S. S. Optimal control analysis of a mathematical model for breast cancer. Math. Comput. Appl. 23(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca23020021 (2018).

Blattman, J. N. & Greenberg, P. D. Cancer immunotherapy: a treatment for the masses. Science 305(5681), 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1100369 (2004).

Parish, C. R. Cancer immunotherapy: the past, the present and the future. Immunol. Cell Biol. 81(2), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0818-9641.2003.01151.x (2003).

O’Byrne, K. J., Dalgleish, A. G., Browning, M. J., Steward, W. P. & Harris, A. L. The relationship between angiogenesis and the immune response in carcinogenesis and the progression of malignant disease. Eur. J. Cancer 36(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00241-5 (2000).

Ribas, A. & Wolchok, J. D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 359(6382), 1350–1355. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar4060 (2018).

Dinku, T., Kumsa, B., Rana, J. & Srinivasan, A. A Mathematical Model of Tumor-Immune and Host Cells Interactions with Chemotherapy and Optimal Control. J. Math. 2024(1), 3395825. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/3395825 (2024).

Kilbas, A. A., Srivastava, H. M. & Trujillo, J. J. Theory and applications of fractional differential equations (Vol. 204). elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-0208(06)80001-0 (2006).

Yang, X. J., Srivastava, H. M. & Machado, J. A. A new fractional derivative without singular kernel: application to the modelling of the steady heat flow. arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.01623. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1601.01623 (2015).

Yeolekar, M. A., Yeolekar, B. M., Khirsariya, S. R. & Chauhan, J. P. Investigation of infertility treatments on infertile couples through fractional-order modeling approach. Int. J. Biomath. 2450155. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793524524501559 (2025).

Chavada, A., Pathak, N. & Khirsariya, S. R. Fractional-order modeling of Chikungunya virus transmission dynamics. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 48(1), 1056–1080. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.10372 (2025).

Jajarmi, A., Hajipour, M. & Baleanu, D. New aspects of the adaptive synchronization and hyperchaos suppression of a financial model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 99, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2017.04.025 (2017).

Özköse, F., Yilmaz, S., Yavuz, M., Öztürk, I., Senel, M. T., Bagci, B. S., Dogan, M. & Önal, Ö. A fractional modeling of tumor-immune system interaction related to lung cancer with real data. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137(1). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-02254-6 (2021).

Khirsariya, S. R., Yeolekar, M. A., Yeolekar, B. M. & Chauhan, J. P. Fractional-order rat bite fever model: a mathematical investigation into the transmission dynamics. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 70(4), 3851–3878. https://doi.org/10.3934/mmc.2024020 (2024).

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Diff. Appl. 1(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.12785/pfda/010201 (2015).

Atangana, A. On the new fractional derivative and application to nonlinear Fisher’s reaction-diffusion equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 273, 948–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2015.10.021 (2016).

Dinku, T., Kumsa, B., Rana, J. & Srinivasan, A. Stability analysis and optimal control of tumour-immune interaction problem using fractional order derivative. Math. Comput. Simul. 233, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2024.12.028 (2025).

Panda, S. K., Karapinar, E. & Atangana, A. A numerical schemes and comparisons for fixed point results with applications to the solutions of Volterra integral equations in dislocatedextendedb-metricspace. Alex. Eng. J. 59(2), 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2020.02.007 (2020).

Yavuz, M. & Özdemir, N. European Vanilla Option Pricing Model of Fractional Order without Singular Kernel. Fractal Fract. 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract2010003 (2018).

Keten, A., Yavuz, M. & Baleanu, D. Nonlocal Cauchy problem via a fractional operator involving power kernel in Banach spaces. Fractal Fract. 3(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract3020027 (2019).

Chavada, A., Pathak, N. & Khirsariya, S. R. A fractional mathematical model for assessing cancer risk due to smoking habits. Math. Model. Control 4(3), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.3934/mmc.2024020 (2024).

Dinku, T., Kumsa, B. & Rana, J. A mathematical approach to cancer growth: The role of smoking through fractional order models with Mittag-Leffler kernels. Alex. Eng. J. 124, 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2025.03.013 (2025).

Chauhan, J. P., Khirsariya, S. R., Yeolekar, B. M. & Yeolekar, M. A. Fractional mathematical model of Listeria infection caused by pre-cooked package food. Res. Control Optim. 14, 100371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rico.2024.100371 (2024).

Yavuz, M. & Abdeljawad, T. Nonlinear regularized long-wave models with a new integral transformation applied to the fractional derivative with power and Mittag-Leffler kernel. Adv. Diff. Equ. 2020(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02828-1 (2020).

Yavuz, M., Ozdemir, N. & Baskonus, H. M. Solutions of partial differential equations using the fractional operator involving Mittag-Leffler kernel. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133(6), 215. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-12051-9 (2018).

de Pillis, L. G. & Radunskaya, A. A mathematical model of immune response to tumor invasion. In Computational fluid and solid mechanics 2003 (pp. 1661–1668). Elsevier Science Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044046-0.50404-8 (2003).

Podlubny, I. Fractional differential equations:an introduction to fractional derivatives, fractional differential equations, to methods of their solution and some of their applications (Academic Press, 1998).

Vargas-De-León, C. Volterra-type Lyapunov functions for fractional-order epidemic systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 24(1–3), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2014.12.013 (2015).

Atangana, A. Mathematical model of survival of fractional calculus, critics and their impact: How singular is our world? Adv. Diff. Equ. (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03494-7 (2021).

Coron, J. M. Control and Nonlinearity (American Mathematical Society, In Mathematical surveys, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1090/surv/136.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (2024/01/31877).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MF, KSN; Investigation: KSN, MF, AA, SA; Methodology: KSN; Writing original draft: KSN, MF, AA, SA; Software: KSN, MF; Validation: KSN

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nisar, K.S., Farman, M., Alotaibi, A.M. et al. Feedback design to measure the effect of therapies in controlling cancer using the fractional approach. Sci Rep 15, 31494 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16977-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16977-4