Abstract

This study explores the potential of Bloch surface waves (BSWs) at the interface of a finite one-dimensional photonic crystal (1D-PC) and vacuum, exploiting spectroscopic ellipsometry in a range that encompasses the mid-infrared (4000 cm-1 to 200 cm-1). BSWs can be excited in both σ and π polarizations, which in the ellipsometric configuration can be detected at the same time, presenting distinct advantages for sensor applications targeting the growth of thin solid films and molecular monolayers, surface-adsorbed gas molecules, and liquid droplets. Compared to other sensing techniques exploiting mid-infrared vibrational absorption lines for chemical-specific sensitivity, like waveguides, nano-antenna arrays, metasurfaces, attenuated total reflectance (ATR) in crystals or in optical fibers, the present approach features high field enhancements, strong field confinement, and large quality factors of the resonances, all while relying on a rather simple and potentially low-cost configuration. The 1D-PCs were fabricated by depositing alternated homogeneous layers out of CaF2 and ZnS with a geometry tailored to sustain BSW with a suitable dispersion in the 5000 cm-1 to 1250 cm-1 range. For the first time to our knowledge, we report the characterization of a sensor based on BSWs in the mid-infrared region using an ellipsometric approach to detect complex reflectivity. Our spectral analysis of mid-infrared 1D-PCs showed clear signatures of σ and π-polarized BSWs and guided modes. Although preliminary, our approach could lead to the development of innovative sensors, enhancing the capabilities of IR ellipsometry by utilizing BSWs in 1D-PCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) is routinely applied across a broad spectral range from deep UV down to the IR1,2,3,4. In particular, infrared (IR)-SE5,6 in the range 4000 cm-1 to 200 cm- 1 (2.5 μm to 50 μm), which encompasses the Mid-IR region (MIR), holds promise for numerous advanced applications in condensed matter physics, such as investigating plasmonic phenomena6,7,8,9,10, waveguiding phenomena11, Mo-doped VO2 thin films deposited on silicon substrates12, and the spectral “fingerprints” of various quasi-particles13,14.

SE relies on the analysis of the change of the polarization state of light upon reflection from either a single interface or a system of interfaces of a multilayer6. Such a change occurs because the reflection introduces different amplitude and phase shifts for electric field components oscillating perpendicular and parallel to the plane of reflection2,15. Consequently, linearly polarized incident light generally becomes elliptically polarized upon reflection depending on the materials and thicknesses. The state of polarization of the reflected light can be described using two ellipsometric parameters: amplitude ratio (\(\text{tan}{\Psi}\)) and phase difference (\({\Delta}\))2,15.

The ability to complement traditional IR spectroscopy by determining the spectral refractive index and gathering comprehensive optical property data has broadened the scope and application of SE. Typically conducted through reflection, SE measurements are viable even when sample absorptivity precludes transmission methods5. Particularly, the capability to probe the vibrational modes of biomolecules13,14, offers opportunities in the field of biosensing16,17,18 and gas sensing19.

In this work, we propose enhancing the SE sensitivity towards changes of the dielectric properties of the structure under investigation by means of the strong field localization provided by surface electromagnetic states, also known as Bloch surface waves (BSWs). BSWs can be excited at the truncation interface between a finite one-dimensional photonic crystal (1D-PC) and vacuum and exhibit an electric field envelope that decays exponentially within both the 1D-PC and the external medium20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, they can be polarized along either the σ or the π polarization direction, offering unique advantages for metrology and sensing applications24. Previous studies demonstrated enhanced resolution of BSW-based sensors in the visible range for detecting molecular species across various contexts22,23,24. The geometry of 1D-PCs allows for tailored design and optimization for specific applications, also in MIR26,27, making them robust even in the presence of structural deviations28,29,30,31.

As far as surface enhanced techniques are concerned, one promising approach is surface-enhanced IR absorption (SEIRA) combined with plasmonic metasurfaces utilizing microfluidic technologies. Such a strategy offers high sensitivity for detecting the target molecules largely due to the enhanced surface sensitivity provided by plasmonic structures, as it has been recently demonstrated for protein aggregates in biofluid samples utilizing immunoassay-based approach32. First applications of surface-enhanced sensing strategies for gas sensing have been proposed18,33,34, although SEIRA for on-chip gas sensing is still not very successful due to the intrinsically weak light-matter interaction33. For various sensing applications, the main advantage of the BSWs approach over SEIRA and metasurfaces is that there is no need of lithographic or other surface patterning techniques. The field enhancement and confinement are entirely generated by the stack of dielectric layers deposited by e.g. RF sputtering or thermal evaporation or electron-beam evaporation. All these techniques can be easily scaled to large-area wafers up to 4 inches diameter or more. The production cost of a sensor chip based on BSWs would be much lower than a lithographically patterned one, also considering that high-resolution lithography is typically required for MIR SEIRA chips8.

1D-PC materials and design

The 1D-PCs were fabricated by depositing alternated homogeneous layers out of CaF2 and ZnS, both showing high transparency and a convenient refractive index mismatch in the MIR spectral range. Based on the literature values of the materials refractive indices35,36, the 1D-PC geometry was tailored to sustain BSW with a suitable dispersion in the \(\text{2.0 - 8.0 }\mu\text{m}\) range, giving rise to the following stack design substrate/ ZnS(1) / CaF2(1) / ZnS(2) / CaF2(2) / ZnS / vacuum, i.e. a two-periods 1D-PC with a top defect layer.

The layers deposition were performed by thermal evaporation of CaF2 and ZnS layers in a high-vacuum chamber, with limiting pressure \(5\cdot{10}^{-7}\) Torr, equipped with two evaporation sources37. By means of trial depositions on sacrificial CaF2 substrates, we found that the refractive indices of the ZnS and CaF2 layers of the 1D-PC are reduced due to the materials’ porosity. To take into account the porosity, we used the Maxwell – Garnett Theory (MGT)38 to calculate the refractive index of the composite material:

where \({\upsilon}_{i}\) is the fraction volume of the inclusions, \({\epsilon}_{i}=1\) the dielectric constant of the included material (vacuum in this case) and \({\epsilon}_{0}\) the dielectric constant of the matrix material (ZnS or CaF2). The MGT is generally assumed valid for \({\upsilon}_{i}\le \pi /6\sim0.52\)39. When analyzing data, we also made use of the Bruggeman theory39, which is assumed valid for \({\upsilon}_{i}\le 1\), and found results that agree with the MGT. Moreover, from the scanning electron microscopy images27 of the 1D-PC used in this work, the inclusions show a lamellar shape with thickness in the order of 30 nm, which makes that the critical thickness, i.e. the minimum film thickness that is necessary to make that the effective medium approximation holds39, is smaller than the physical thickness of the CaF2(1) and CaF2(2) layers.

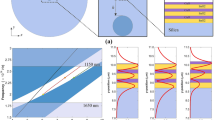

3D maps of the dip minimum ((a) and (b)) and of the angular position ((c) and (d)) of the BSW when the higher (ZnS) and the lower (CaF2) refractive indexes layer thicknesses are spanned in a range of \(\text{300 nm}\) and \(\text{400 nm}\), respectively. The simulations are carried out for \(\lambda=5\:\mu\text{m}\). The simulations are carried out for both the \(\sigma\) ((a) and (c)) and the \(\pi\) ((b) and (d)) polarizations.

In Fig. 1, we present the primary characteristics of the BSW resonance: specifically, the amplitude of the resonance dip (\({R}_{min}\), (a) and (b)) and the angular position (\({\theta}_{BSW}\), (c) and (d)). These characteristics are calculated at a wavelength \(\lambda=5\:\mu\text{m}\) and for a ZnS/CaF2 bi-periodic structure with 3% and 18% porosity, respectively, topped with a 200 nm ZnS layer deposited on a CaF2 substrate. The maps are generated by varying the layer thicknesses of the materials with high (ZnS) and low (CaF2) refractive indices that form the periodic unit within the following ranges: \(\:0.80\le\:{l}_{ZnS}\le\:1.10\:\mu\text{m}\) and \(\:2.10\le\:{l}_{Ca{F}_{2}}\le\:2.40\:\mu\text{m}\), respectively. Simulations are conducted for both transverse electric (\(\sigma\), (a) and (c)) and transverse magnetic (\(\pi\), (b) and (d)) polarizations. In the figure, we highlight the values assumed by the reflectivity and the angular resonance position when the layer thicknesses are equal to \(1.00\:\mu\text{m}\) for ZnS and \(2.20\:\mu\text{m}\) for CaF2. The chosen structure offers a favorable balance between resonance depth and angular positioning, remaining well within the angular acceptance of the experimental setup. Specifically, across the examined thickness range and specified wavelength interval, for both the polarizations, the BSW resonance consistently lies above the critical angle for total internal reflection (TIR, approximately 44° to 48° depending on the wavelength) and below the acceptance angle of the mirror system used in our setup (approximately 75°).

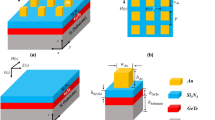

The 1D-PCs were deposited on CaF2 truncated prisms (Korth Kristalle) with a \({\theta}_{\text{0}}\text{=55}^{ \circ }\) base angle, which were adopted to operate in a Kretschmann-Raether (KR) configuration under TIR conditions (Fig. 2a)27,40. TIR operation allows us to explore the angular region beyond the vacuum light-line where the BSW dispersions are located20. In the following, \(\varvec{\beta}\) and \({\varvec{k}}_{\varvec{x}}\) are the parallel and perpendicular components of the incidence wavevector \(\varvec{k}\), within the prism and with respect to the 1D-PC interfaces. From focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) analysis of the cross-section image of a 1D-PC deposited on a sacrificial test substrate27, we retrieved the real thicknesses of the layers that were 0.90(±0.02) / 2.30(±0.07) / 0.890(±0.025) / 2.25(±0.10) / 0.20(±0.02) µm, respectively. The 1D-PC surface profile had a rms roughness \({\text{R}}_{\text{q}}\text{~32 nm}\)27.

(a) Sketch of the Kretschmann-Raether configuration. The prism is quoted and the radiation wavevector \(\varvec{k}\) has been decomposed in its parallel, \(\varvec{\beta}\), and perpendicular, \({\varvec{k}}_{\varvec{x}}\), components. (b) Sketch of the experimental apparatus. FTIR Infrared source (FTIR IR source); plane mirror (PM); focusing mirror (FM); iris (I); Kretschmann-Raether configuration (KR); rotational motorized stage (MS); the polarizer (P) tuned to 45°; analyzer (A).

The material refractive index dispersion is evaluated by means of the Sellmeier model reported in refs.35 and 36 for CaF2 and ZnS, respectively. As in the ref.27, making use of a Maxwell-Garnett model38, we evaluated the void/full ratio of the materials, which was approximately 2–3% for ZnS, and 18±2% and 21±3% for CaF2(1) and CaF2(2) layers, respectively. In Fig. 3, we present the reflectance map calculated for the deposited structure for both \(\sigma\) (a) and \(\pi\) (b) polarizations. The reflectance maps show that the fabricated structure supports not only surface-localized modes but also internally confined electromagnetic modes, known as guided modes (GMs)27. In the maps, the dispersion of both types of modes is indicated with black arrows. Moreover, numerical simulations27 have showed, in agreement with the literature28, that the 1D-PC design is robust towards the random fluctuations of the thicknesses of the layers arising from the fabrication accuracy29,30,31. As illustrated in Fig. 3(c), for the \(\sigma\) polarization, the 1D-PC design exhibits a good robustness against random fluctuations of the layers’ thicknesses and porosity (3% tolerance). A statistical analysis of the simulation data allows extracting the BSW resonance angular and depth variability intervals at \(\lambda=5\:\mu\text{m}\) (and \(\lambda=6\:\mu\text{m}\)). The resonance was found at \({\theta}_{BSW}\pm{3\sigma}_{\theta}=63.2^\circ\pm2.2^\circ\) (\(58.4^\circ\pm1.8^\circ\)), with a corresponding depth of \({D}_{BSW}\pm3{\sigma}_{D}=0.96\pm 0.09\) (\(0.73\pm0.11\)). Such results indicate that the structure maintains its functionality even when there are variations in the layers properties which can arise from inevitable fabrication inaccuracies.

Reflectance maps calculated for the deposited 1D-PC in the case of (a) \(\sigma\) polarization and (b) \(\pi\) polarization. The black arrows highlight the dispersions of the BSW and GM modes. (c) \(\sigma\) polarized reflectance profiles calculated for \(\lambda=5\:\mu\text{m}\) (black) and \(\lambda=6\:\mu\text{m}\) (red) considering a 3% variability in both the thicknesses and the refractive indices of the structure’s layers.

Results and discussion

Experimental method

The ellipsometric parameters can be derived from intensity measurements and are directly related to the four Stokes parameters (\({S}_{0}\), \({S}_{1}\), \({S}_{2}\), \({S}_{3}\), more details in the “Setup Calibration” Appendix), which provide a comprehensive description of the polarization state of light1,2,5,15. In the context of ellipsometry, these parameters can be determined experimentally by measuring the intensity of light under specific polarizer settings15.

In the present study, the IR measurements were carried out by means of a Bruker Vertex 70v interferometer. A globar source was used in conjunction with a broadband beamsplitter in silicon and a nitrogen cooled MCT detector (Infrared Associates Inc). The interferometer operated in low vacuum (2–3 hPa) to eliminate IR absorption from the atmospheric water vapor and CO2.

A custom optical set-up was built to measure the MIR spectra of the 1D-PC in the Kretschmann-Raether configuration, and was placed in the sample compartment of the interferometer, as sketched in Fig. 2b. The IR input beam is linearly polarized by a polarizer (P) tuned to 45°, and passes through an iris (I) (diameter \(\text{1.5 mm}\)) in order to readily produce a quasi-collimated beam with diameter smaller than the size of the prism facet. The reflected signal was collected by plane (PM, Thorlabs PFE10-M01) and focusing mirrors (FM). Both the rotational motor stage (MS) and the polarizer localized after the prism, i.e. the analyzer (A), were remotely controlled, in order to perform several measurements without the need to break the vacuum in the interferometer. In Fig. 2b, \({E}_{\sigma}\) and \({E}_{\pi}\) denote the components of the electric field corresponding to \(\sigma\) and \(\pi\) polarizations, respectively. The experimental measurements were carried out in the frequency (wavelength) range between \(\text{1000 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{10.0 }\upmu \text{m}\)) and \(\text{3250 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{3.1 } \upmu \text{m}\)). The prism is aligned so that the light beam impinges on its lateral facet with normal incidence. This condition guarantees an initial incidence angle \(\theta\) equal to the prism cut angle \({\theta}_{0}\). It is noteworthy that the incidence angle could be affected by a systematic error too, which was estimated to be not larger than 1°. The motorized rotational stage used to vary the incidence angle had a precision of \(\text{0.25}^{ \circ }\) and ensured a \(\theta\) dynamical range of about 4° without the need to realign the custom optical set-up. Before performing any measurements, we conducted a setup calibration procedure in order to collect the reference signals \({\text{I}}_{{{\text{ref}}}} (\upnu ,\varphi_{{\text{A}}} {\text{,}}\theta{\text{)}}\) shown in Fig. 8 (see the “Setup Calibration” Appendix).

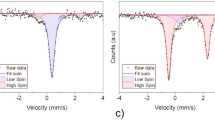

Experimental (a and b) and theoretical (c and d) reflectance spectra \(R\left(\upnu,{\varphi}_{A},\theta\right)\) obtained for the four different values of \({\varphi}_{A}\) and \(\theta\) equal to \({\theta}_{0}\) (a and c) and \({\theta}_{1}\) (b and d). The dashed lines and the coloured areas highlight the frequency where experimentally and theoretically the \(\sigma\) (0°) (black) and \(\pi\) \(\text{(90}^\circ)\) (green) BSW and GMs are observed.

Coated Prism measurements

The experimental spectral intensities \({\text{I}}(\upnu,\varphi _{{\text{A}}} {\text{)}}\) reflected by the prism topped by the 1D-PC, were collected at \({\upphi}_{\text{P}}\text{=45}^{ \circ}\) and for two values of the incidence angle \({\theta}_{\text{0}}\text{=}\text{}\text{55.0}^{ \circ } \pm \text{0.5}^{ \circ }\) and \({\theta}_{\text{1}}\text{=}\text{}\text{57.9}^{ \circ } \pm \text{0.5}^{ \circ }\), with a spectral resolution of \(\text{0.25 c}{\text{m}}^{\text{-1}}\). In Fig. 4, we show the reflectance spectra, \({\text{R(}}\upnu,\upphi _{{\text{A}}} {\text{,}}\theta {\text{)}}\), obtained for the four different settings of the analyzer, \({\upphi}_{\text{A}} {\text{ = 0}}^{ \circ },\:{\text{45}}^{ \circ },\:{\text{90}}^{ \circ },\:{\text{135}}^{ \circ }\) (\(\sigma\), \(\mathcal{A}\), \(\pi\), \(\mathcal{C}\), respectively) for both incidence angles \({\theta}_{0}\) (Fig. 4a) and \({\theta}_{1}\) (Fig. 4b). The \(\text{R}\left(\upnu,{\upphi}_{\text{A}}\text{,}\theta\right)\) curves were obtained by normalizing the measured intensity signal, \(\text{I}\left(\upnu,{\upphi}_{\text{A}}, \theta\right)\), by the reference spectra \({\text{I}}_{{{\text{ref}}}} ({{\upnu}},{{\upphi}}_{{\text{A}}} {\text{,}}\theta {\text{)}}\). To accurately determine the reflectance profile, \(\text{R}\left(\upnu, {\upphi}_{\text{A}}\text{,}\theta\right)\), the acquired signals undergo post-processing to eliminate any unwanted signal loss due to misalignment in the experimental setup. The sample (\(S\)) and reference (\(B\)) signals, shown in Fig. 5a, are first normalized by dividing each by its respective maximum value, resulting in the normalized curves \({S}_{N}\) and \({B}_{N}\), shown in Fig. 5b. The normalized sample signal \({S}_{N}\) is then divided by the normalized reference \({B}_{N}\), and subsequently by a normalization factor \(\Upsilon_{C}\). As illustrated in Fig. 8, this factor accounts for the fact that the intensity reflected by the bare prism in the aligned configuration (\(\mathcal{A}\)) is consistently lower than the sum of the intensities in the \(\sigma\) and \(\pi\) configurations (\(2{S}_{0}\)). The normalization factor \(\Upsilon_{C}\) is therefore calculated as follows:

In conclusion, all the reflectance profiles are evaluated as in the following:

With reference to the Fig. 4(a) and (b), different features can be recognized in the reflectance spectra. The frequency where either \(\sigma\) or \(\pi\) polarized BSW are excited become evident when the \(\sigma\) (black) and the \(\pi\) (green) polarized radiation is collected. Such frequencies are highlighted by the black (σ) and green (π) dotted lines. In particular, in the case of \(\theta={\theta}_{0}\) (and \(\theta={\theta}_{1}\)), the dips frequencies are evaluated to be at \({\upnu}_{\upsigma}\text{= 1630 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{1800 c}{\text{m}}^{\text{-1}}\)) and \({\upnu}_{\pi}\:\text{= 2230 c}{\text{m}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{2580 c}{\text{m}}^{\text{-1}}\)) for the σ and the π polarized BSW, respectively. All the data related to the BSW frequencies are summarized in Table 1.

Plot of the amplitude (a), \(\text{tan}{\Psi}\), and of the phase (b), \({\Delta}\), of the complex reflectance of the 1D-PC retrieved experimentally (thicker solid lines) and theoretically (thinner solid lines) for both the incidence angles (\({\theta}_{0}\) (red) and \({\theta}_{1}\) (black)). c) Plot of the \(AoLP\) (thicker curves, left axis) and its derivative (thinner curves, right axis).

The experimental reflectance can be properly reproduced by means of numerical simulations, in which the reflected electric field is expressed as24:

where \(\widehat{i}\) and \(\widehat{j}\) are the unit vectors of the \(\sigma\) and the \(\pi\) polarization directions, respectively; \({r}_{\sigma}\left(\upnu\right)=\left|{r}_{\sigma}\right|{e}^{j{\phi}_{\sigma}}\) and \({r}_{\pi}\left(\upnu\right)=\left|{r}_{\pi}\right|{e}^{j{\phi}_{\pi}}\) are the reflection coefficients for the \(\sigma\) and the \(\pi\) polarizations, respectively. Based on the real 1D-PC geometry and materials’ optical properties, the numerical simulation of the reflection coefficients was carried out by a proprietary transfer-matrix method (TMM) code24. The square modulus of the reflected electric field can be calculated and, finally, we can write the reflectance expression as:

with \({C}_{\sigma}={f}_{\sigma\:}{cos}{\varphi}_{A}\) and \({S}_{\pi}={f}_{\pi\:}{sin}{\varphi}_{A}\); \({\Delta}\phi={\phi}_{\sigma}-{\phi}_{\pi}\) and \(\varPhi\) considers for any phase difference between the \(\sigma\) and \(\pi\) components introduced along the optical path. \({f}_{\sigma}\) and \({f}_{\pi}\) are the correction factors retrieved from the calibration procedure (see the Appendix). We plot in Fig. 4(c) and (d), the theoretical plots obtained by the simulations carried out according to the Eq. (5). In the theoretical case of \(\theta={\theta}_{0}\) (and \(\theta={\theta}_{1}\)), the dips frequencies are evaluated to be at \({\upnu}_{\upsigma}\text{=1635 c}{\text{m}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{1860 c}{\text{m}}^{\text{-1}}\)) and \({\upnu}_{\pi}\text{=2120 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{2364 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\)) for the σ and the π polarized BSW, respectively (see Table 1).

The theoretical curves well reproduce the experimental curves. The missing of the complete matching between the curves can be due to different reasons, for example, the simplified model used to simulate the multilayer didn’t consider any losses due to scattering between the layer interfaces. Furthermore, the discrepancy could be also due to the uncertainty related to the porosity of the used materials and to the layer thicknesses. Moreover, as can be seen from the plots, it can be noted the presence of few absorption peaks that can be present in the materials that constitute the 1D-PC. In particular, vibrational absorption of C-H stretching lines typical of organic compounds accidentally present on the 1D-PC surface and in the CaF2 voids can be observed around \(\upnu = \text{3000 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\). Noteworthy, the plot of the π-polarized reflectance also allows us to identify several sharp absorption peaks below \(\text{1500 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) that are instead almost negligible with σ polarization. We assign these peaks to vibrational absorptions of the thin protecting coating of the gold planar mirrors present in the setup.

For \(\theta={\theta}_{0}\) (\({\theta}_{1}\)), from simulations for the σ-polarized case at \(\upnu = \text{2580 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\:\text{2820 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\)), we determined that the GM is evidenced by a broad, low-intensity dip. In the experimental reflectance profile shown in Fig. 4(a) and (b), the dip associated with the GM is highlighted by a black dotted line, but it is not clearly distinguishable.

Discussion

To deeply investigate the data collected, we carried out the complex reflectance from the following2,5,15:

The comparison between the experimental and theoretical results for the parameters in Eq. (6) is shown in panels (a) and (b) of Fig. 6. In these panels, we present the ellipsometer parameters \(\text{tan}{\Psi}\) and the phase \({\Delta}\), obtained experimentally (thicker solid line) and theoretically (thinner solid line) for the incidence angles \({\theta}_{0}\) (red) and \({\theta}_{1}\) (black).

In Fig. 6(a), the dips associated with the parameter \(\text{tan}{\Psi}\) are clearly distinguishable, corresponding to the excitation of \(\sigma\)-polarized BSWs at the frequencies \(\text{1630 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{6.13 }\upmu \text{m}\)) and \(\text{1800 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (\(\text{5.56 }\upmu \text{m}\)) at \({\theta}_{0}\) (red dotted line) and \({\theta}_{1}\) (black dotted line), respectively. These frequencies confirm the BSW frequencies identified through the reflectance spectrum shown earlier. In Fig. 6(b), the σ-polarized BSWs are characterized by s-shaped curves in the complex reflectivity phase, in contrast to the \(\pi\)-polarized BSWs and GMs, which show only a steep variation in the complex reflectivity phase. As previously observed, the numerical simulations qualitatively reproduce the experimental curves well.

(a) Plot of the amplitude, \(\text{tan}{\Psi}\), and phase, \({\Delta}\), of the complex reflectance calculated in a hypothetical experiment at the incidence angle \({\theta}_{0}\), where a porous layer of ZnS* is directly deposited on a bare prism (black) and on a 1D-PC topped prism (red). The inset shows a magnified view of the \({\Delta}\) plot around the frequencies where the BSW is excited. (b) Refractive index dispersion of the ZnS* layer, constituted by the ZnS with the 3% porosity filled with the fictious gas.

In Fig. 6(c), we plot the angle of linear polarization (\(AoLP\)) evaluated as in the following15:

In Fig. 6(c), we also present its derivative curve (\(d\text{AoLP}/d\upnu\), right axis), which effectively highlights the excitation frequencies of both BSWs and GMs. The derivative curve remains approximately constant around zero, except for a few frequencies where it exhibits a dip or a peak. These indicate the frequencies where the function \(AoLP\left(\upnu\right)\) shows a maximum or minimum slope, depending on the polarization of the BSW or GM. When the \(AoLP\) is closer to \(45^\circ\), it suggests that the radiation interacts with the samples without altering its polarization. Conversely, when the \(AoLP\) crosses the \(0^\circ\) angle, it indicates σ or π polarization of the reflected radiation, due to the selective absence of the π and σ components, respectively. In other words, when a σ mode (BSW or GM) is excited, only a π component will be detected, and vice versa.

In Fig. 7a, we plot numerical results for the amplitude, \(\text{tan}{\Psi}\), and phase, \({\Delta}\), of the complex reflectance in the case of a hypothetical ellipsometric measurement. The calculations are performed when the illumination beam is impinging on the sample at the incidence angle \({\theta}_{0}\) for two different systems. The first one (red curves) is the CaF2 prism topped by the same 1D-PC characterized above, but the \(\text{200 nm}\) ZnS cap layer has been substituted with a ZnS* layer, where the 3% porosity has been filled with a fictitious gas with an absorption peak at \(\text{1650 }{\text{cm}}^{\text{-1}}\) (ZnS*, Fig. 7b). The second one is a bare prism topped only with the same 3% porous layer of ZnS*. Starting from the microscopic model, the complex refractive index dispersion of the fictitious gas (\({\stackrel{\sim}{n}}_{i}\left(\omega\right)={n}_{i}\left(\omega\right)+i{\kappa}_{i}\left(\omega\right)\)) can be written as in the following41:

where \(N\) is the number of absorption peaks in the considered frequency range and, in this case, is equal to 1. \(A=0.02\), \(\text{w}=5\:nm\) and \({\lambda}_{0}=6.06\:\mu\text{m}\) (\({\upnu}_{0}=1650\:{\text{cm}}^{-1}\)) are the amplitude, the width and the central wavelength of the fictitious absorption peak introduced in the material, respectively. \(\lambda\left(\omega\right)\) can be written as \(2\pi c/\omega\).

For the ZnS material, again, we used the dispersion provided in the ref36. (\({\stackrel{\sim}{n}}_{ZnS}\)). As above, making use of a Maxwell-Garnett model38, we evaluated the refractive index dispersion of the material ZnS*, where the 3% porosity of the ZnS layer (\({\upsilon}_{i}=0.03\)) is filled with the fictitious gas characterized by the dispersion \({\epsilon}_{i}={\stackrel{\sim}{n}}_{i}^{2}\), whereas \({\epsilon}_{0}={\stackrel{\sim}{n}}_{ZnS}^{2}\). The equation provides the dispersion shown in Fig. 7b.

As shown in the Fig. 7a, the absorption peak is detectable in the \(\text{tan}{\Psi}\) curve in both cases. Notably, by subtracting the absorption peak due to the excitation of the BSW when the 1D-PC is present using a multi-peak analysis procedure (pink baseline in figure), we can evaluate that the fictitious absorption peak is five times deeper than in the case without the 1D-PC. Similarly, in the case of the \({\Delta}\) plot, the absorption peak is indicated by an abrupt change in the curve when the 1D-PC is present, unlike when it is absent. In the second case, the \({\Delta}\) curve appears substantially unperturbed. The inset shows a magnified view of the \({\Delta}\) plot around the frequencies where the BSW is excited.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have, to the best of our knowledge, presented the first characterization of a surface sensor based on BSWs in the MIR region, employing an ellipsometric scheme to probe its complex reflectivity. Our spectral analysis of MIR 1D-PCs revealed distinct signatures of both \(\sigma\) and \(\pi\)-polarized BSWs and GMs.

In the landscape of techniques based on MIR absorption spectroscopy, our numerical simulations demonstrate the potential of the BSW sensor for enhanced surface gas detection by exploiting the distinct absorption features associated with fundamental vibrational and rotational transitions19, which represent one of the most challenging objectives in sensing applications. While our experimental results are preliminary, we believe this approach opens new avenues for the development of advanced surface sensors, extending the capabilities of infrared ellipsometry and potentially improving both sensitivity and selectivity.

A practical implementation of the BSW concept for gas sensing applications could follow the path established by BSW-based gas and biosensors in the visible range42,43. In those cases, compact sensing platforms were developed that rely on microfluidic elements to bring the sample fluid into contact with the sensor surface, with detection performed using either single quantum cascade laser sources or QCL combs44.

MIR BSW also hold promise for broader applications in material science, including detailed studies of low-dimensional systems such as topological insulators45, phonon overtones in hybrid perovskites46, and Dirac-like electronic dispersions in doped graphene47. The high-quality factor, high surface field enhancement, double-polarization capability and strong evanescent field confinement at the surface are all features that may be exploited in purposely designed spectroscopic experiments for the characterization of 2D materials or thin epitaxial layers. In this respect, one should consider that the surface of 1D-PC sustaining BSW is flat with low surface roughness (standard deviations of the order of few nanometers). This facilitates both the deposition and study of these materials, that can be free from the challenges of the position-dependent strain that typically occurs when the flakes are placed on non-planar patterned substrates, such as metasurfaces or nanoantenna arrays48,49.

Appendix: Setup calibration

With reference to Fig. 2b, when the input polarizer (P) is set at \({\varphi}_{P}=45^\circ\) relative to the normal to the plane of incidence (note that when \({\varphi}_{P}=0^\circ\) or \({\varphi}_{P}=90^\circ\) the beam is either σ or π polarized, respectively) and the analyzer is set to \({\varphi}_{A}=0^\circ\) (\(\sigma\)), \({\varphi}_{A}=45^\circ\) (aligned polarizers, \(\mathcal{A}\)), \({\varphi}_{A}=90^\circ\) (\(\pi\)), and \({\varphi}_{A}=135^\circ\) (crossed polarizers, \(\mathcal{C}\)), the intensity \(I\left(\upnu,{\varphi}_{A}\right)\) at the detector can be expressed as2,5,15:

From Eq. (9), it is simple to work the Stokes parameters, which can be expressed as:

The Stokes parameters are related to the ellipsometric parameters \({\Psi}\) and \({\Delta}\) by the following Eqs.2,5,15:

In practical applications, several factors must be considered to ensure accurate measurements. When unpolarized IR radiation enters the ellipsometer, the resulting polarization and the detected intensity can be influenced by the optical properties of the ellipsometer components50. Such a partial contribution to the polarization state needs to be accounted for during data analysis. In the present work, the front polarizer is fixed and only \({\varphi}_{A}\) is varied; therefore, a calibration routine has been performed to take into account for any polarization-dependent detection variations50 by measuring the intensity curves of the radiation reflected by a CaF2 bare prism, \(\:{\text{I}}_{\text{ref}}\text{(} \upnu,{\varphi}_{A}\text{,}\theta\text{)}\). We acquired the reference spectra for different incidence angles \(\theta\), but not relevant difference between them emerged. As an exemplary case, in Fig. 8, we show the spectra \({\text{I}}_{\text{ref}}\text{(} \upnu,{\varphi}_{A}\text{,}{\theta}_{0}\text{)}\). We can note that the intensity of the \(\sigma\) component is, in general, smaller than the intensity of the π component. In particular, as reported in ref50. in the case of a rotating analyzer ellipsometer, such a difference can be due to a polarization-dependent sensitivity of the detector, that we can take into account by means of correction factors, which we evaluate to be \({f}_{\sigma}=0.831\) and \({f}_{\pi}=1.144\) for the σ and the π polarization, respectively.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are included in the article.

References

Azzam, R. M. A. & Bashara, N. M. Ellipsometry and Polarized Light (North Holland, 1977).

Fujiwara, H. Spectroscopic Ellipsometry: Principles and Applications (Wiley, 2007).

Politano, G. & Versace, C. Spectroscopic ellipsometry: advancements, applications and future prospects in optical characterization. Spectrosc. J. 1, 163–181 (2023).

Wen, S. et al. Metasurface array for single-shot spectroscopic ellipsometry. Light Sci. Appl. 13 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01396-3 (2024).

Roseler, A. IR spectroscopic ellipsometry: instrumentation and results. Thin Solid Films. 234, 307–313 (1993).

Schubert, M. Infrared Ellipsometry on Semiconductor Layer Structures: Phonons, Plasmons, and Polaritons (Springer, 2005).

Hillier, J., Camelio, S., Cranton, W., Nabok, A. & Mellor, C. K. D. Kalfagiannis, N. When ellipsometry works best: a case study with transparent conductive oxides. ACS Photonics. 7, 2692–2702 (2020).

Adato, R. & Altug, H. In-situ ultra-sensitive infrared absorption spectroscopy of biomolecule interactions in real time with plasmonic Nanoantennas. Nat. Commun. 4, 2154. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3154 (2013).

Schwarz, B. et al. Monolithically integrated mid-infrared lab-on-a-chip using plasmonics and quantum cascade structures. Nat. Commun. 5, 4085. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5085 (2014).

Taliercio, T. & Biagioni, P. Semicond. Infrared Plasmon. Nanophotonics 8, 949–990 (2019).

Dubroka, A. et al. Dynamical response and confinement of the electrons at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 156807. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.156807 (2010).

Amador-Alvarado, S. et al. Temperature-dependent infrared ellipsometry of Mo-doped VO2 thin films across the insulator to metal transition. Sci. Rep. 10, 8555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65279-4 (2020).

Balan, V. et al. Vibrational spectroscopy fingerprinting in medicine: from molecular to clinical practice. Materials 12, 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12182884 (2019).

Lu, F., Jin, M. & Belkin, M. Tip-enhanced infrared nanospectroscopy via molecular expansion force detection. Nat. Photon. 8, 307–312 (2014).

Chipman, R., Lam, W. & Young, G. Polarized Light and Optical Systems (Taylor & Francis Group, 2019).

Bellamy, L. The Infrared Spectra of Complex Molecules (3rd edition London: Chapman and Hall, (1975).

Pinto, G. et al. Spectroscopic ellipsometry investigation of a sensing functional interface: DNA SAMs hybridization. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 2200364. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202200364 (2022).

Rodrigo, D. et al. Mid-infrared plasmonic biosensing with graphene. Science 349, 165–168 (2015).

Popa, D. & Udrea, F. Towards integrated Mid-Infrared gas sensors. Sensors 19, 2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19092076 (2019).

Joannopoulos, J., Johnson, S., Winn, J. & Meade, R. Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Yeh, P., Yariv, A. & Hong, C. Electromagnetic propagation in periodic stratified media. I. General theory. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 67, 423–438 (1977).

Konopsky, V., Karakouz, T., Alieva, E., Vicario, C. & Sekatskii, S. Dietler G. Photonic crystal biosensor based on optical surface waves. Sensors 13, 2566–2578 (2013).

Konopsky, V. & Alieva, E. Photonic crystal surface waves for optical biosensors. Anal. Chem. 79, 4729–4735 (2007).

Sinibaldi, A. et al. A full ellipsometric approach to optical sensing with Bloch surface waves on photonic crystals. Opt. Exp. 21, 23331–23344 (2013).

Toma, K. et al. Bloch surface wave-enhanced fluorescence biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 43, 108–114 (2013).

Smolik, G., Descharmes, N. & Herzig, H. Toward Bloch surface Wave-Assisted spectroscopy in the Mid-Infrared region. ACS Photonics. 5, 1164–1170 (2018).

Occhicone, A. et al. Spectral characterization of Mid-Infrared Bloch surface waves excited on a truncated 1D photonic crystal. ACS Photonics. 8, 350–359 (2021).

Anopchenko, A. et al. Effect of thickness disorder on the performance of photonic crystal surface wave sensors. Opt. Express. 24, 7728–7742 (2016).

Fan, S., Villeneuve, P. & Joannopoulos, J. Theoretical investigation of fabrication-related disorder on the properties of photonic crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 78, 1415–1418 (1995).

Kaliteevski, M., Beggs, D., Brand, S., Abram, R. & Nikolaev, V. Statistics of the eigenmodes and optical properties of one-dimensional disordered photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. E. 73, 056616. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.73.056616 (2006).

Bragheri, F., Faccio, D., Romagnoli, M., Krauss, T. & Roberts, J. Effects of random and systematic perturbations in a one-dimensional photonic crystal wavelength converter. Phys. Rev. E. 70, 017601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.70.017601 (2004).

Kavungal, D. et al. Artificial intelligence–coupled plasmonic infrared sensor for detection of structural protein biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg9644. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adg9644 (2023).

Chong, X. et al. Surface-Enhanced infrared absorption: pushing the frontier for On-Chip gas sensing. ACS Sens. 3, 230–238 (2018).

Bareza, N. J. et al. Phonon-Enhanced Mid-Infrared CO2 gas sensing using Boron nitride nanoresonators. ACS Photonics. 9, 34–42 (2022).

Malitson, I. A. Redetermination of some optical properties of calcium fluoride. Appl. Opt. 2, 1103–1107 (1963).

Debenham, M. Refractive indices of zinc sulfide in the 0.405-13 µm wavelength range. Appl. Opt. 23, 2238–2239 (1984).

Mahan, J. Physical Vapor Deposition of Thin Films (Wiley, 2000).

Markel, V. Introduction to the Maxwell Garnett approximation: tutorial. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 33, 1244–1256 (2016).

Braun, M. M. & Pilon, L. Effective optical properties of non-absorbing nanoporous thin films. Thin Solid Films. 496, 505–514 (2006).

Kretschmann, E. & Raether, H. Radiative decay of Non radiative surface plasmons excited by light. Z. Naturforschung A. 23, 2135–2136 (1968).

Hecht, E. & Optics (4th ed., San Francisco, CA: Adelphy University, (2002).

Rizzo, R. et al. Bloch surface wave label-free and fluorescence platform for the detection of VEGF biomarker in biological matrices. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 255, 2143–2150 (2018).

Konopsky, V. & Alieva, E. Photonic crystal surface mode imaging biosensor based on wavelength interrogation of resonance peak. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 276, 271–278 (2018).

Hugi, A., Villares, G., Blaser, S., Liu, H. C. & Faist, J. Mid-infrared frequency comb based on a quantum cascade laser. Nature 492, 229–233 (2012).

Nucara, A. et al. Infrared study of the quasi-two-dimensional electron system at the interface between SrTiO3 and crystalline or amorphous LaAlO3. Phys. Rev. B. 97, 155126. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.155126 (2018).

Araujo, P. Anharmonicities in phonon combinations and overtones in bilayered graphene: A temperature-dependent approach. Phys. Rev. B. 97, 205441. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.205441 (2018).

Kamal, C. Massless Dirac fermions in stable two-dimensional carbon-arsenic monolayer. Phys. Rev. B. 100, 205404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.205404 (2019).

Sortino, L. et al. Enhanced light-matter interaction in an atomically thin semiconductor coupled with dielectric nano-antennas. Nat. Commun. 10, 5119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12963-3 (2019).

Poumirol, J. M. et al. Unveiling the optical emission channels of monolayer semiconductors coupled to silicon Nanoantennas. ACS Photonics. 7, 3106–3115 (2020).

Gong, M. et al. Calibration of residual polarization in light source for broadband rotating polarizer spectroscopic ellipsometer. Thin Solid Films. 769, 139739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2023.139739 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Research, under the complementary actions to the PNRR “D34Health - Digital Driven Diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics for sustainable Health care” Grant # PNC0000001, project code B53C22006120001. Funded by the European Union program “Next Generation EU”, Mission 4, Component 1, grant PRIN 2022, CUP F53D23001190006. L. Baldassarre acknowledges financial support from the PNRR MUR Project (No. PE0000023-NQSTI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Occhicone, F. Michelotti., A. Nucara, L. Baldassarre, A. Sinibaldi, and M. Ortolani: Conceptualization. A. Occhicone, F. Michelotti: writing—original draft preparation. A. Occhicone, F. Michelotti, R. Polito, V. Giliberti: figure preparation, data analysis and investigation. A. Occhicone, A. Sinibaldi, F. Michelotti: 1D-PC design. M. Pea, A. Notargiacomo, S. Cibella, F. Mattioli: 1D-PC fabrication. M. Ortolani, L. Baldassarre, A. Nucara, F. Michelotti: supervision and funding acquisition. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Occhicone, A., Pea, M., Polito, R. et al. Mid-infrared ellipsometry enhanced by means of localized electromagnetic states of a one-dimensional photonic crystal. Sci Rep 15, 32004 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17011-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17011-3