Abstract

Nepeta persica is a medicinal plant with significant pharmacological potential, primarily attributed to its high nepetalactone content. Understanding the environmental drivers of nepetalactone biosynthesis is essential for optimizing both cultivation and conservation strategies. In this study, we combined machine learning algorithms (random forest, support vector machines, gradient boosting machines) with a hybrid ensemble model (RF-SVM-GBM), alongside statistical approaches (generalized linear models [GLM] and partial least squares [PLS]) and geospatial analyses (GIS, remote sensing, habitat suitability modeling) to assess the influence of climatic, topographic, and edaphic factors on nepetalactone concentration in N. persica across Fars province, Iran. The results identified elevation, south-facing slopes, and mean annual temperature as the most critical determinants of nepetalactone accumulation. The hybrid ensemble model demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy, reducing RMSE by 21.1% (RMSE = 0.015) compared to individual models. Habitat suitability maps revealed Marvdasht and Shiraz counties as the most favorable regions for cultivating N. persica with high nepetalactone concentrations, followed by smaller high-suitability zones in Northeast Firozabad and Northern Kazerun. In contrast, areas such as Abadeh, Eqlid, and Khorrambid exhibited lower suitability. These findings provide actionable insights for precision agriculture, resource-efficient cultivation, and climate-adaptive conservation of medicinal plants. By integrating ecological modeling with machine learning, this research offers a scalable, data-driven framework to support the sustainable production of high-value secondary metabolites in environmentally challenging regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nepeta persica (Lamiaceae) is a medicinally significant species widely distributed in arid and semi-arid regions of Iran and Afghanistan1. Traditionally, it has been used for treating gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory ailments, and nervous system conditions, reflecting its broad pharmacological potential2. Recent advancements in phytochemical analysis, particularly gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), have enhanced our understanding of its bioactive molecules, reinforcing its medicinal relevance. Given the growing demand for natural bioactive compounds in pharmaceutical industries, identifying the environmental and ecological drivers influencing their accumulation is a crucial research focus3.

N. persica is rich in secondary metabolites, including essential oils, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and iridoid monoterpenes, which contribute to its pharmacological efficacy. Among these, nepetalactone—a bicyclic monoterpenoid—stands out as the most biologically active compound4. Its diverse isomeric forms significantly influence bioactivity, particularly in insect repellency, where it rivals synthetic alternatives like DEET, making it a promising candidate for eco-friendly pest control5. Additionally, nepetalactone has exhibited potent sedative and anxiolytic effects by modulating GABAergic pathways, which supports its traditional use for stress relief and insomnia6. Beyond neurological applications, it has demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy and possesses strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, potentially contributing to neuroprotective and cardioprotective effects7. Given its diverse pharmacological activities, optimizing cultivation strategies to enhance nepetalactone biosynthesis remains essential to medicinal plant research.

The biosynthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in N. persica, particularly nepetalactone, are strongly influenced by climatic, edaphic, and topographic factors. Environmental conditions such as temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and humidity regulate key metabolic pathways involved in terpenoid synthesis8. Studies indicate that moderate drought stress can enhance nepetalactone production, as water scarcity often triggers secondary metabolite accumulation as part of the plant’s adaptive response. Soil characteristics—including texture (sand, silt, and clay fractions), pH, electrical conductivity (EC), organic matter content, and macronutrient availability (N, P, and K)—significantly shape metabolite profiles9,10. Well-drained, nutrient-rich soils with moderate organic content promote enzymatic activity involved in metabolite biosynthesis11. Additionally, topographic parameters such as elevation, slope aspect, and curvature influence microclimatic conditions, which, in turn, affect secondary metabolite concentrations12.

Recent advancements in remote sensing and geospatial technologies have transformed environmental analysis by enabling precise, large-scale mapping of ecological determinants13. Sentinel-2 satellite imagery, with its high spatial and spectral resolution, was utilized in this study to indirectly derive key climatic variables, including surface temperature and precipitation proxies, through spectral indices and empirical modeling approaches14. While ground-based climate monitoring often suffers from limited spatial coverage, Sentinel-2 provides continuous and detailed spectral information across heterogeneous landscapes, which, when integrated with field observations, allows for improved spatial assessment of nepetalactone-rich regions. The Alaska satellite contributes critical topographic data, essential for understanding elevation-driven variations in metabolite accumulation15while Google Earth Engine (GEE) facilitates large-scale environmental data processing, enabling efficient extraction of topographic and hydrological parameters16. Geographic Information System (GIS) platforms integrate these datasets, facilitating spatial modeling and predictive mapping of optimal growth zones for N. persica17.

Habitat suitability modeling (HSM) is a powerful tool for predicting the potential distribution of plant species based on environmental factors18. By integrating species distribution data with climatic, soil, and topographic variables, HSM helps identify optimal habitats, assess ecological constraints, and inform conservation strategies19. In this study, a qualitative approach was employed, as habitat predictions were based on measured nepetalactone content rather than simple species occurrence, ensuring a more precise understanding of factors influencing secondary metabolite accumulation. The effectiveness of HSM largely depends on the selection of predictive algorithms capable of capturing complex, non-linear ecological relationships20.

Among machine learning-based HSM approaches, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm is widely recognized for its robustness and predictive accuracy20. As an ensemble method, RF constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their outputs, making it well-suited for complex ecological datasets21. Its ability to handle high-dimensional environmental variables and rank predictor importance has made it increasingly popular in habitat suitability modeling22,23. Given the focus on nepetalactone concentration rather than species presence, RF provides the flexibility needed for modeling secondary metabolite patterns across heterogeneous landscapes.

To ensure methodological rigor, complementary algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) were also considered. SVM effectively handles nonlinear relationships in complex datasets, while GBM improves model precision through iterative learning24,25. Additionally, hybrid ensemble models combining RF, SVM, and GBM have demonstrated superior generalization by integrating the distinct strengths of each algorithm26. These integrated approaches enhance predictive reliability when dealing with multifactorial ecological systems, such as those governing nepetalactone accumulation in N. persica.

So, the main goals of this study were:

-

(1)

Identifying the most significant climatic, edaphic, and topographic factors driving nepetalactone biosynthesis in N. persica, leveraging advanced phytochemical and geospatial analyses to establish causal linkages between environmental variables and metabolite accumulation.

-

(2)

Integrating remote sensing (Sentinel-2, Alaska satellite) and GIS technologies for high-resolution mapping of environmental predictors, enabling robust spatial modeling of nepetalactone-rich habitats across heterogeneous landscapes.

-

(3)

Developing a multi-algorithm habitat suitability model (HSM) that prioritizes nepetalactone concentration over species presence, employing a comparative framework of machine learning techniques—Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM)—and hybrid ensemble approaches to optimize predictive accuracy.

-

(4)

Comparing the performance of RF, SVM, GBM, and ensemble models in capturing non-linear ecological relationships and predicting zones of high secondary metabolite productivity, with emphasis on algorithmic robustness, variable importance, and resistance to overfitting.

-

(5)

Generating ensemble-based, high-resolution predictive maps of optimal cultivation zones for N. persica, and integrating model outputs to guide sustainable harvesting, conservation prioritization, and climate-resilient agricultural practices.

Materials and methods

Study area

This research was conducted in Fars Province, located in southern Iran (27°02′–31°42′ N, 50°42′–55°36′ E) (Fig. 1), covering an area of approximately 122,000 km². The province exhibits diverse topographic and ecological conditions, ranging from arid lowlands to temperate highlands, making it an ecologically heterogeneous region well-suited for medicinal plant research. Elevations vary significantly from approximately 450 m in the southwestern lowlands to over 4,000 m in the Zagros Mountain range, creating substantial spatial gradients that influence vegetation patterns, soil composition, and the distribution of medicinal plants27,28. N. persica primarily thrives in montane and foothill ecosystems, where moderate water availability, well-drained soils, and microclimatic stability promote its growth and secondary metabolite production29. The dominant soil types in the study area were calcareous soils with sandy-loam to clay-loam textures, moderate organic matter content, and slightly alkaline pH, factors known to influence secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Hydrological features, including seasonal rivers, ephemeral streams, and groundwater resources, further contribute to habitat heterogeneity and ecological dynamics30,31. Given its environmental variability and ecological significance, Fars Province serves as an ideal case study for assessing how climatic, edaphic, and topographic factors drive habitat suitability and secondary metabolite accumulation in N. persica.

Study area in Fars province, Southwest Iran (ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). Available at: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

Methodology

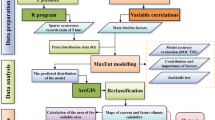

This study, conducted in Fars Province, Iran, identified N. persica at 62 locations. Secondary metabolites were extracted using a Clevenger apparatus and analyzed via gas chromatography (GC) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). A total of 18 environmental variables—encompassing climatic, topographic, and edaphic factors—were processed and converted into raster layers with 30-meter resolution using GIS (ArcGIS Desktop 10.8). Four machine learning models were used to predict nepetalactone concentration: random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), gradient boosting machine (GBM), and a hybrid ensemble model (RF–SVM–GBM). The most influential environmental drivers were identified using partial least squares (PLS) regression and generalized linear models (GLM). Model performance was assessed using four evaluation metrics: root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R²), and concordance correlation coefficient (CCC). The final habitat suitability map highlighted optimal ecological zones for high nepetalactone accumulation across Fars Province. Figure 2 illustrates the overall methodology of the study.

Habitat identification and data collection

Field sampling was conducted in Fars Province, Iran, to identify and document the natural habitat of N. persica. Preliminary distribution data were obtained from the provincial Agricultural Jihad Organization, guiding targeted field surveys. A stratified sampling approach was used to cover diverse environmental conditions, ensuring comprehensive habitat representation. At each confirmed location, geographic coordinates were recorded using GPS, and both plant and soil samples were collected (Fig. 3). Aerial parts of the plant, including leaves and flowers, were harvested at their peak vegetative stage, while the soil samples were taken from the same points. The samples were transported to the laboratory for chemical analysis. This method ensured precise documentation of N. persica distribution while maintaining scientific rigor in sample collection and habitat characterization.

Plant sampling was conducted during May and June 2024, strategically aligned with the reproductive phase of N. persica, a stage well-documented for the peak accumulation of secondary metabolites, including nepetalactone32,33. Considering the topographic and climatic heterogeneity of Fars Province, sampling commenced in the warmer lowland areas during early May and gradually progressed towards higher elevation, cooler regions throughout June. This approach ensured that all samples were collected during a comparable developmental stage of the species, thereby minimizing phenological variability in metabolite profiles.

A total of 62 sampling sites were selected based on the confirmed occurrence records of N. persica, derived from field surveys and distributional data provided by the Agricultural Jihad Organization of Fars Province. It is important to note that the species exhibits a naturally fragmented and ecologically constrained distribution, which inherently limits the number and spatial density of viable sampling locations. Despite these limitations, previous studies have demonstrated that sample sizes ranging from 50 to 100, when properly distributed, can provide statistically robust insights into the spatial patterns of plant secondary metabolite production, even in ecologically complex regions34,35.

Isolation and analysis of essential oils

The aerial parts of N. persica were shade-dried at ambient temperature (25 ± 2 °C). Fifty grams of the dried material were subjected to hydrodistillation with 500 mL of distilled water using a Clevenger-type apparatus36. The isolation was conducted for 4 h under standardized conditions (100 °C, atmospheric pressure) to maximize concentration while minimizing artifact formation. The obtained essential oils were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) coupled with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) for quantification and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for compound identification37. GC-MS spectra were cross-referenced with the NIST 2020 mass spectral library and authentic standards where available. Special emphasis was placed on nepetalactone due to its established bioactivity, though the full volatile profile was characterized to assess compositional diversity. This dual analytical approach provided comprehensive qualitative and quantitative data on the essential oil constituents, ensuring reliable metabolite identification.

Preparing environmental factor maps

To assess the potential distribution of suitable habitats for N. persica across the study area, we evaluated three environmental variables: climatic, topographic, and edaphic factors. From these categories, 18 variables were meticulously selected based on their ecological significance to the species’ growth and the reliability of the data sources. The selection process was guided by ecological principles and the feasibility of obtaining consistent data, ensuring that the variables accurately reflected the environmental conditions impacting the species’ habitat preferences38. This thorough approach was vital for improving the precision and reliability of the predictive model.

Edaphic factors

In this research, 62 soil samples were collected from various N. persica habitats, with depths ranging from 0 to 30 cm. These samples were air-dried at room temperature and sifted through a 2-mm mesh to prepare them for laboratory analysis. Laboratory tests were performed to assess soil characteristics, including organic matter (OM), electrical conductivity (EC), pH, and the proportions of sand, silt, clay, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Soil texture was analyzed using the hydrometer method39while pH was determined with an electronic pH meter40. Nitrogen content was measured using the Kjeldahl method41potassium was extracted using ammonium acetate42phosphorus was evaluated via the Olsen method43and organic matter was quantified using the Walkley-Black technique44. Electrical conductivity was determined by creating a soil-water suspension and analyzing it with an EC meter45.

The laboratory-derived soil properties were spatially interpolated using the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method to generate high-resolution thematic maps for the study area46. A total of nine raster maps were produced, representing key soil variables such as organic matter (OM), electrical conductivity (EC), pH, and the proportions of sand, silt, clay, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) (Fig. 4A–I). These maps provided a detailed spatial representation of soil characteristics, enhancing the environmental predictor dataset for subsequent habitat suitability modeling of N. persica.

Given the naturally fragmented distribution of N. persica populations, coupled with the rugged, mountainous terrain of the study area, the spatial distribution of samples was inherently irregular and limited in density. As a result, the application of geostatistical methods such as Kriging, which requires a sufficiently dense, homogeneous, and regularly spaced dataset to construct a reliable variogram, was not feasible.

Therefore, IDW was selected as the sole interpolation technique, in line with established recommendations for ecological studies under constrained sampling conditions47,48,49. IDW provides deterministic, distance-weighted estimations without relying on strict assumptions regarding spatial autocorrelation, making it particularly appropriate for heterogeneous landscapes.

To evaluate the accuracy of the interpolation outputs, a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure was implemented for each soil variable. The resulting Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values ranged from ± 0.12 to ± 0.28 standardized units across different soil parameters, indicating acceptable interpolation accuracy for ecological modeling purposes in mountainous environments.

Climatic factors

To generate high-resolution spatial maps of temperature and precipitation across the study area, we utilized Sentinel-2 multispectral satellite imagery, complemented by ground-based meteorological data from the Iranian Meteorological Organization (IRIMO). The Sentinel-2 system provides 13 spectral bands, including visible, near-infrared, and shortwave infrared (SWIR) wavelengths, which are essential for estimating key environmental variables50.

All satellite imagery and ground observations used in this study correspond to a five-year reference period (2019–2023), ensuring that the derived climate variables reflect multi-year average conditions rather than short-term anomalies.

In total, 480 cloud-free Sentinel-2 scenes were acquired and processed using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform and Sentinel Hub services. Atmospheric correction was applied using the Sen2Cor algorithm to minimize the effects of atmospheric scattering and cloud contamination51. All imagery was resampled to a consistent spatial resolution of 30 m and clipped to the study area boundary for further analysis.

Although Sentinel-2 does not carry dedicated thermal infrared sensors, several studies have demonstrated that Land Surface Temperature (LST) can be effectively estimated using SWIR bands (Bands 11 and 12) and ancillary topographic data52.

We applied a regionally calibrated empirical model based on the split-window algorithm expressed as:

Where:

B11 and B12 represent Sentinel-2 shortwave infrared bands, sensitive to surface moisture and heat emission; Elevation was derived from a Digital Elevation Model (DEM); Time of Acquisition accounts for solar angle effects on surface heating.

The resulting LST maps represent the multi-year mean annual surface temperature for the period 2019–2023. The accuracy of LST estimation was assessed based on prior validation studies in similar mountainous terrains, with typical uncertainties ranging from ± 1.5 °C to ± 2 °C.

Precipitation, although not directly measured by Sentinel-2, was estimated using a vegetation-based proxy model, calibrated with local ground observations.

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), derived from Bands 4 (Red) and 8 (Near-Infrared), serves as an indicator of vegetation productivity, which correlates with water availability. Additionally, the SWIR band (B11) was used as a proxy for atmospheric moisture. The precipitation model is expressed as:

Where:

P is the estimated mean annual precipitation (mm/year); a, b, and c are empirical coefficients derived from calibration with ground-based rainfall data.

Calibration of the precipitation model utilized observational records from 32 synoptic meteorological stations distributed across Fars Province. These stations ensure broad spatial coverage, capturing variations across different elevations and climatic zones.

The precipitation model achieved a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.76 and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of ± 47 mm/year, indicating acceptable predictive accuracy for large-scale ecological modeling in arid and semi-arid environments. The estimated precipitation maps correspond to the multi-year mean annual precipitation for the period 2019–2023.

All final temperature and precipitation maps were produced in raster format with a 30-meter spatial resolution and integrated into the GIS database for further spatial analysis (see Fig. 4J, K).

Topographic factors

Topographic features play a crucial role in environmental and ecological modeling as they influence climate conditions, soil properties, vegetation distribution, and hydrological processes53. In this research, Alaska satellite images were utilized to extract key topographic parameters, including elevation, slope, slope direction (aspect), and surface curvature. The Alaska satellite images provided high-resolution Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), which enabled the precise extraction of topographic factors54.

Elevation represented the height above sea level and was directly extracted from the DEM raster layer. Slope measured the steepness or inclination of the terrain and was calculated as the rate of change in elevation. Aspect defined the direction a slope was facing, measured in degrees from north (0°) to west (360°). Curvature describes the concavity or convexity of the land surface, which influences water flow and soil erosion.

To account for anthropogenic impacts on habitat dynamics, road and river network vector data were integrated into the analysis. Using ArcGIS’s Euclidean distance algorithm, these linear features were transformed into continuous raster surfaces, quantifying proximity to the nearest road and river. The derived layers were resampled to a consistent 30-meter spatial resolution to align with other factors. All input layers underwent z-score standardization to ensure comparability and facilitate their incorporation into machine learning-based habitat suitability models. Following spatial harmonization (coordinate system alignment and clipping to the study area boundary), the anthropogenic and topographic predictors were incorporated into the analytical framework (Fig. 4L and R).

18 raster layers represent key variables categorized into three groups: Edaphic (A: Clay percent; B: Silt percent; C: Sand percent; D: Electrical conductivity; E: pH; F: Phosphorus; G: Potassium; H: Nitrogen; I: Organic matter); Climatic (J: Mean annual rainfall; K: Mean annual temperature); Topographic (L: Slope aspect; M: Elevation; N: Plan curvature; O: Profile curvature; P: Slope degree; Q: Distance from rivers; R: Distance from roads). (ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). Available at: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

Habitat suitability prediction

Modeling using the random forest algorithm

The random forest (RF) algorithm, an ensemble learning method introduced by Breiman55 was employed to model the habitat suitability of N. persica based on multiple environmental predictors. RF constructs an ensemble of decision trees, each trained on a bootstrap sample of the dataset, and combines their outputs to improve predictive performance21. The algorithm is particularly effective for handling high-dimensional and nonlinear relationships between predictors, making it well-suited for ecological and environmental modeling56.

RF was implemented using the random Forest package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForest/index.html) in R (version 4.3.2) with 500 trees. The optimal number of predictor variables randomly selected at each split was determined through cross-validation to minimize the Out-Of-Bag (OOB) error.

RF constructs an ensemble of decision trees T1, T2, …, Tn, where each tree Ti is trained on a bootstrap sample. The final prediction for an input x is determined by aggregating the outputs of individual trees:

where n represents the number of trees. For classification tasks, majority voting is used, whereas for regression tasks, the average of tree predictions is taken. The importance of each predictor variable Xj is quantified based on its contribution to model accuracy:

Where \(\:{A}_{i}\:\)is the accuracy of tree iii before permutation and \(\:{A}_{i}^{*}\) is the accuracy after permuting \(\:{X}_{j}\).

Modeling using the gradient boosting machine

Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) is an ensemble learning method that builds predictive models sequentially by optimizing weak learners, typically decision trees, to minimize a predefined loss function57. Unlike Random Forest, which builds independent trees, GBM constructs trees iteratively, where each tree corrects the errors of the previous ones, improving model performance58. This approach makes GBM highly effective for complex, nonlinear ecological and environmental modeling tasks25.

GBM was implemented using the xgboost package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/xgboost/index.html) in R (version 4.3.2), with hyperparameters tuned via cross-validation. The learning rate, maximum depth of trees, and the number of boosting iterations were optimized to enhance model accuracy while preventing overfitting.

In GBM, the prediction function is formulated as a sum of weak learners:

where \(\:{F}_{m}\left(x\right)\:\)is the model at the \(\:m-th\) iteration, is the weak learner, and \(\:\gamma\:\) is the learning rate. The model minimizes a loss function \(\:{h}_{m}\left(x\right)\) using gradient descent:

Variable importance in GBM is determined using the gain metric, representing the contribution of each predictor to reducing the loss function at each split in the decision trees.

Modeling using the support vector machines

Support vector machines (SVM) is a supervised learning algorithm that constructs a hyperplane in a high-dimensional space to separate data into different classes or predict continuous values in regression tasks59. SVM is particularly effective for handling small datasets with high-dimensional feature spaces, making it suitable for ecological modeling24.

SVM was implemented using the e1071 package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/e1071/index.html) in R (version 4.3.2), with the radial basis function (RBF) kernel to capture complex nonlinear relationships between environmental predictors and habitat suitability. The optimal values for the regularization parameter \(\:C\) and kernel width \(\:\gamma\:\) were determined via cross-validation.

For classification tasks, SVM finds an optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between classes:

where w is the weight vector, \(\:b\) is the bias term, and \(\:yi\) represents class labels.

For regression tasks (support vector regression, SVR), the model minimizes the following objective function:

where \(\:C\) controls the trade-off between model complexity and error tolerance \(\:\in\:\). The importance of predictor variables in SVM was assessed using sensitivity analysis, evaluating how variations in each feature affect model predictions.

Before model training, all predictor variables were screened for multi-collinearity using two complementary diagnostic tests: The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance values. Variables with a VIF exceeding 5 or a Tolerance below 0.2 were considered indicative of significant multi-collinearity60. Such variables were either excluded from the final modeling dataset or combined with other correlated predictors to reduce redundancy. This pre-processing step ensured the stability and interpretability of the models while minimizing distortions in variable importance rankings.

Hybrid ensemble modeling

Hybrid ensemble models integrate multiple machine learning algorithms—such as random forest (RF), support vector machines (SVM), and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM)—to enhance predictive accuracy and generalization. These models leverage the complementary strengths of individual algorithms while mitigating their limitations by combining outputs through techniques such as weighted averaging or stacking61.

In this research, hybrid modeling was implemented using the SuperLearner package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SuperLearner/index.html) in R (version 4.3.2). Two ensemble strategies were applied:

Weighted averaging

The final prediction (\(\:{\hat{y}}\)) was computed as a weighted sum of the individual model predictions:

Where, \(\:{\hat{y}}\_RF\), \(\:{\hat{y}}\_SVM\), and \(\:{\hat{y}}\_GBM\) are predictions from RF, SVM, and GBM models, respectively; \(\:{w}_{1}\), \(\:{w}_{2}\), and \(\:{w}_{3}\) are non-negative weights summing to 1, optimized through grid search to minimize the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) on a held-out validation set (20% of the data).

The optimal weights obtained were: w₁ = 0.46 (RF), w₂ = 0.29 (SVM), and w₃ = 0.25 (GBM).

Stacking (meta-learner approach)

In stacking, a meta-learner combines base model predictions to refine final outputs:

Where \(\:f\) represents the meta-learner function. A linear regression model was used as the meta-learner due to its interpretability and low susceptibility to overfitting62.

To prevent information leakage and overfitting, we employed a nested cross-validation scheme: An outer 5-fold cross-validation split the dataset into training and testing subsets; Within each training fold, an inner 5-fold cross-validation optimized both base models and meta-learner parameters.

This approach ensures that the meta-learner is trained exclusively on out-of-fold predictions, thus maintaining model integrity and unbiased performance estimation.

Machine learning model optimization and hyperparameter tuning

To ensure model transparency and reproducibility, all machine learning algorithms underwent systematic hyperparameter optimization using a grid search combined with 5-fold cross-validation63. The optimized parameter values for each algorithm are summarized in (Table 1). Specifically, random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and gradient boosting machines (GBM) were individually tuned to maximize predictive performance based on minimizing the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Subsequently, an ensemble hybrid model (RF-SVM-GBM) was constructed by integrating the outputs of the three models using a weighted averaging approach, where model weights were assigned proportionally to their coefficient of determination (R²) values on the validation dataset.

Pinpointing the dominant factor

Partial least squares (PLS)

The Partial least squares (PLS) is a multivariate statistical method used to model relationships between independent variables (predictors) and dependent variables (responses)64. Unlike traditional regression techniques, PLS is particularly effective when predictor variables are highly collinear, making it suitable for ecological studies where environmental factors are often correlated65. PLS was applied using the pls package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pls/index.html) in R (version 4.3.2) to identify the most influential environmental factors affecting the presence of N. persica. The optimal number of latent components was determined using cross-validation to minimize prediction error. The importance of each variable was assessed using Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores, where variables with VIP > 1 were considered significant contributors.

PLS reduces dimensionality by extracting latent components (score vectors) that maximize covariance between predictors \(\:\stackrel{-}{X}\) and \(\:\stackrel{-}{Y}\) response. The method follows these steps:

Where in \(\:X\) is the predictor matrix, \(\:Y\) is the response matrix, \(\:T\) represents score vectors, \(\:P\) and \(\:C\) are loading matrices, \(\:E\) and \(\:F\) are residual matrices.

PLS finds the projection that maximizes the covariance between \(\:\stackrel{-}{T}\)and \(\:\stackrel{-}{Y}\). The regression coefficient is computed as:

\(\:\widehat{\beta}\) represents the estimated regression coefficients. The importance of each predictor \(\:{X}_{j}\) is evaluated using:

Where \(\:{S}_{h}\) is the explained variance for component \(\:h\), \(\:{W}_{jh}\)is the weight of predictor\(\:{X}_{j}\) in component \(\:h\), \(\:p\) is the total number of predictors.

To determine the optimal number of latent components, we implemented a leave-one-out cross-validation strategy, minimizing the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP). Model performance was assessed using multiple evaluation metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R²), predictive ability (Q²), and RMSEP values. The importance of each predictor was quantified using Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores, with variables exceeding a VIP threshold of 1 considered significant contributors. Additionally, a Scree Plot was generated to visualize the variance explained by each PLS component, enhancing the interpretability of the dimensionality reduction process.

Generalized linear model (GLM)

The Generalized Linear Model (GLM) extends the capabilities of traditional linear regression by allowing the response variable to follow distributions beyond the normal, providing flexibility in ecological and environmental modeling where data may deviate from ideal statistical assumptions66,67.

GLM was applied to evaluate the influence of environmental variables on the continuous concentration of nepetalactone in N. persica. The model was implemented using the glm package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glm.predict/index.html) in R (version 4.3.2).

Given the continuous nature of the response variable, a Gaussian distribution with an identity link function was used. This approach is mathematically equivalent to standard linear regression but was adopted within the GLM framework to accommodate potential deviations from constant variance or normality assumptions in the residuals. The GLM formulation follows:

Where \(\:g\left(0\right)\) is the link function (for continuous responses), \(\:E\left[Y\right]\) is the expected nepetalactone concentration, \(\:{X}_{1}\:to\:{X}_{p}\) represent the environmental predictors, \(\:{\beta}_{0}\) is the intercept, \(\:{\beta}_{i}\) are the regression coefficients.

Model parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The statistical significance of each predictor was evaluated using the Wald test, computed as:

Where \(\:{\widehat{\beta}\:}_{j}\) is the estimated coefficient for predictor \(\:{X}_{p}\), and SE(\(\:{\widehat{\beta}\:}_{j}\)) is its standard error. Predictors with statistically significant coefficients were interpreted as key environmental drivers of nepetalactone biosynthesis.

This GLM analysis complemented the PLS results by providing an independent statistical assessment of the relationship between environmental variables and metabolite concentration, consistent with established approaches in ecological research68.

Results

Predictor selection and multi-collinearity mitigation

To ensure model robustness, multi-collinearity among predictor variables was systematically assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF) thresholds (VIF > 5 indicating problematic collinearity). Diagnostic analysis identified significant collinearity between profile curvature and key terrain-derived variables. Although profile curvature is ecologically relevant to N. persica habitat dynamics, its high collinearity with other topographic variables introduced statistical redundancy, leading to its exclusion from the final model. To mitigate bias and maintain model parsimony, profile curvature was excluded from the final variable set. The refined predictors (Table 2) strike a balance between statistical independence and ecological relevance, optimizing explanatory power while preserving interpretability. This approach explicitly incorporates key environmental interactions, such as the combined effects of topography, soil properties, and climate variables, ensuring the model’s capacity to accurately disentangle the complex drivers of habitat suitability.

Spatial variability of nepetalactone concentration across sampling sites

The quantitative analysis of nepetalactone concentration across 62 sampling sites in Fars Province, performed using Gas Chromatography (GC), revealed substantial spatial heterogeneity, with measured values ranging from 20.79 to 89.64% (Table 3). This wide variability highlighted the substantial influence of localized environmental factors on the biosynthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in N. persica. The high-resolution GC-based quantification ensures precise determination of nepetalactone levels, providing robust evidence that variations in edaphic properties, climatic conditions, and topographical gradients play a critical role in modulating metabolite synthesis. These findings emphasize the necessity of integrating spatial analysis with chemical profiling to better understand the ecological drivers of phytochemical diversity in medicinal plant populations.

The GC-FID chromatograms (Figs. 5A and 6B) represented the secondary metabolite profiles of N. persica with a focus on the identification of nepetalactone. In Fig. 5A, the chromatogram displays dominant late-eluting peaks, including the critical nepetalactone peak at ~ 17.728 min, confirming its presence as a key bioactive compound. Additional late-stage peaks (e.g., 21.158, 32.038 min) suggested the co-elution of structurally complex secondary metabolites, such as sesquiterpenes or oxygenated derivatives, which require prolonged retention under specific GC conditions. Conversely, Fig. 5B is characterized by prominent early-eluting peaks (e.g., 4.827, 5.223 min), likely corresponding to volatile monoterpenes or low molecular weight metabolites. Despite these differences, nepetalactone remains consistently detected at ~ 17.712 min, underscoring its stability across analytical setups.

Comparative analysis of predictive accuracy in machine learning algorithms for nepetalactone concentration modeling

The predictive accuracy of the individual machine learning models (RF, SVM, GBM) and the hybrid ensemble approach (RF-SVM-GBM) was evaluated under a stratified 10-fold cross-validation scheme to ensure robustness and minimize bias due to data partitioning (Table 4). For each fold, the root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R2), and concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) were computed, and the mean values across all folds were reported as overall performance indicators.

The hybrid ensemble model consistently demonstrated superior predictive performance, achieving the lowest RMSE (0.015), the lowest MAE (0.012), the highest R² (0.82), and the strongest agreement between observed and predicted values (CCC = 0.88). Compared to the best-performing standalone model (Random Forest), the ensemble reduced RMSE by 21.1%, confirming the synergistic advantage of integrating RF’s feature importance weighting, SVM’s boundary optimization, and GBM’s iterative error correction.

The confidence intervals (CI) for RMSE were derived from the fold-wise distribution of errors across the 10 cross-validation runs. For the hybrid model, the RMSE 95% CI ranged from 0.012 to 0.018, indicating low variability in predictive error across folds. Although the dataset comprised 62 observations, the stratified cross-validation structure ensured that each fold maintained representative ecological and environmental variability, contributing to stable model estimates.

Standalone models showed comparatively weaker performance: Random Forest (RMSE = 0.019, R2 = 0.74, CCC = 0.81), Support Vector Machine (RMSE = 0.021, R2 = 0.68, CCC = 0.76), and Gradient Boosting Machine (RMSE = 0.028, R2 = 0.54, CCC = 0.63). Residual diagnostics, including residual distribution plots and spatial autocorrelation analysis (Moran’s I, p > 0.05), indicated no significant model bias or spatial clustering of residuals, supporting the validity of the predictive framework across heterogeneous landscapes.

Analysis of environmental factors influencing nepetalactone concentration in N. persica

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the environmental factors that significantly influence the concentration of nepetalactone in N. persica, a medicinal plant native to the Fars province. To achieve this, we employed two robust statistical modeling approaches: The partial least squares (PLS) regression (Fig. 6A) and the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) (Fig. 6B). These methods allowed us to quantify the relative contributions of various environmental variables, thereby facilitating the development of a predictive model for spatial variations in nepetalactone concentration.

The results of our analysis revealed that elevation, slope aspect, and mean annual temperature were the most influential environmental factors governing nepetalactone biosynthesis in N. persica (Fig. 6A, B). These three variables collectively accounted for a substantial proportion of the model’s explained variance, underscoring their critical role in defining the optimal ecological conditions for the species’ secondary metabolite production.

Among the examined variables, elevation was found to be the most significant determinant of nepetalactone concentration. Our findings indicated that specific altitudinal ranges were conducive to the accumulation of this bioactive compound (Fig. 4M). The second most influential environmental variable was slope aspect, with southern-facing slopes exhibiting higher favorability for nepetalactone accumulation (Fig. 4L). Mean annual temperature was identified as the third most important factor influencing nepetalactone concentration (Fig. 4K).

The PLS model achieved robust predictive performance, with an R2 value of 0.62, indicating that 62% of the variance in nepetalactone concentration was explained by the selected environmental predictors. The model’s cross-validated predictive ability (Q²) was 0.57, and the RMSEP was 0.019 standardized units. These metrics confirm the reliability of the model in capturing the key environmental drivers. Furthermore, the Scree Plot of explained variance per component (Fig. 6C) illustrates that the first three latent components accounted for the majority of the variance, supporting the dimensionality reduction applied.

Spatial prediction in habitat suitability for nepetalactone optimization

SVM-GBM hybrid ensemble model alongside individual machine learning algorithms (random forest, support vector machine, gradient boosting machine). These models were employed to predict spatial patterns of habitat suitability with respect to environmental factors previously identified as influential for nepetalactone biosynthesis (e.g., elevation, slope aspect, temperature). The outputs were classified into five suitability categories: very low, low, medium, high, and very high (Fig. 7A–D).

To facilitate the spatial interpretation of continuous habitat suitability predictions, the model outputs were reclassified into five categories using the Jenks Natural Breaks optimization method. This classification approach minimizes within-class variance while maximizing between-class differences, providing an objective basis for visualizing gradients in nepetalactone suitability across the landscape. The classification thresholds were determined independently for each model output, ensuring consistency in interpretation while preserving the distinct spatial patterns generated by the different algorithms.

The RF-SVM-GBM hybrid ensemble demonstrated the most spatially explicit predictions, delineating regions with varying levels of suitability across the Fars Province. Based on this model, 5.24% of the total area (3006.04 km²) was classified as very high suitability, and 20.06% (11,512.93 km²) as very low suitability zones (Figs. 8 and 9A). These outputs reflect the integration of topographic, edaphic, and climatic gradients influencing habitat conditions.

Habitat suitability maps for nepetalactone concentration predicted using four machine learning algorithms: RF-SVM-GBM hybrid ensemble (A), RF (B), SVM (C), and GBM (D). (R (version 4.3.2). Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.3.2/)

Random forest (RF), known for capturing complex nonlinear ecological relationships, identified 7.37% (4228.76 km²) of the area as highly suitable. RF’s capacity to detect micro-environmental variability, particularly linked to elevation and slope, contributed to its detailed mapping of favorable zones — factors recognized as critical for nepetalactone biosynthesis. Moreover, RF classified a broader extent of combined high and very high suitability zones, totaling 25.81% (14,813.13 km²) of the landscape (Figs. 8 and 9B), underscoring its sensitivity to subtle environmental gradients.

Support vector machine (SVM) yielded a more conservative estimation, with 1.25% (720.19 km²) designated as very high suitability (Figs. 8 and 9C). This likely reflects SVM’s stricter boundary definitions, emphasizing distinct habitat separation while potentially underestimating transitional or ecotonal areas.

Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) classified 5.34% (3065.68 km²) of the area as highly suitable (Figs. 8 and 9D), with a tendency to highlight abrupt ecological thresholds, such as elevation breaks, affecting habitat favorability.

The comparatively conservative outputs of the GBM model, which classified only 5.34% of the landscape as highly suitable for nepetalactone optimization, likely reflect the inherent regularization mechanisms within the algorithm. To minimize overfitting, the GBM was configured with a conservative learning rate (0.05) and elevated regularization parameters (subsample = 0.7, max_depth = 4), promoting precise but more restrictive delineation of suitable habitats. This trade-off between precision and generalization is consistent with established GBM behavior in ecological applications.

To ensure that these conservative predictions were not a consequence of model underfitting, performance metrics (RMSE, MAE, R², CCC) were monitored across all cross-validation folds, with no indication of systematic bias or degraded accuracy for GBM relative to other models. Furthermore, spatial calibration was conducted by overlaying observed nepetalactone concentrations onto the predicted suitability maps. A positive spatial correlation (Spearman’s ρ = 0.71, p < 0.01) confirmed that regions classified as highly suitable by GBM generally corresponded to areas with elevated compound accumulation, validating the ecological relevance of the model outputs.

Overall, the ensemble approach integrated the strengths of individual models, enhancing spatial prediction stability while mitigating overfitting and model-specific biases. Spatial heterogeneity in habitat suitability was evident across the province, with variations among counties reflecting complex environmental interactions. Figure 10 presents the aggregated habitat suitability patterns derived from the hybrid model, illustrating distinct spatial clusters of favorable regions.

Habitat suitability for N. persica in Fars province, highlighting optimal regions for nepetalactone production based on the RF-SVM-GBM hybrid model. (R (version 4.3.2). Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.3.2/).

Discussion

This research demonstrates the complex interactions between environmental factors and nepetalactone biosynthesis in N. persica, a medicinal plant of ecological and pharmacological significance in arid and semi-arid landscapes. By integrating machine learning algorithms with geospatial and statistical analyses, we identified elevation, slope aspect, and mean annual temperature as the dominant predictors of spatial variability in nepetalactone concentration across Fars Province.

The effectiveness of the RF-SVM-GBM hybrid ensemble model highlights the methodological advantage of combining multiple algorithms to address the inherent complexity of ecological data. The ensemble model outperformed standalone RF, SVM, and GBM in terms of predictive accuracy, confirming that integrating the strengths of different algorithms—such as RF’s capacity for handling nonlinear interactions, SVM’s hyperplane optimization, and GBM’s iterative error correction—reduces bias and enhances generalization, in line with recent advances in ecological modeling69,70,71,72.

Our results emphasize that elevation plays a pivotal role in shaping nepetalactone accumulation patterns in N. persica. Similar to other Lamiaceae species, optimal biosynthesis occurred within a specific altitudinal range, likely reflecting the influence of altitude on microclimatic conditions such as temperature stability, solar radiation, and soil moisture availability73,74,75. This finding is consistent with studies reporting that altitude-driven environmental gradients modulate secondary metabolite production through their effects on plant stress responses and resource allocation76,77.

Slope aspect emerged as the second most influential environmental determinant, with southern-facing slopes associated with higher nepetalactone concentrations. This result supports previous observations that aspect-related variations in solar exposure can significantly affect plant physiology, phenolic composition, and terpenoid pathways, especially under semi-arid conditions78,79,80. In regions such as Fars Province, where water availability is limited and temperature extremes are common, micro-topographic factors like slope aspect can create localized environmental niches that favor secondary metabolite biosynthesis81.

However, in semi-arid Fars Province, southern slopes receive prolonged solar irradiance (1,800–2,200 kWh/m²/yr), which drives photosynthetic rates (Amax = 15–18 µmol CO₂/m²/s) and carbohydrate allocation to glandular trichomes—the primary sites of nepetalactone storage82. Enhanced UV-A/B exposure on these slopes is known to upregulate phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthetic pathways, which increase the accumulation of antioxidant and photoprotective compounds. This metabolic response indirectly stabilizes monoterpenes against photooxidative degradation by reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and reinforcing cellular defense systems. Similar UV-induced protective mechanisms have been demonstrated in several aromatic and medicinal plants, including Thymus vulgaris and Mentha piperita83,84.

Mean annual temperature, although a broad climatic variable, also showed a strong association with nepetalactone concentration. Our reliance on multi-year averages aimed to capture long-term environmental influences rather than short-term fluctuations. While it is acknowledged that daily or seasonal temperature extremes may influence metabolic pathways85 the use of mean temperature as a predictor is widely accepted in large-scale ecological modeling and provides a stable baseline for understanding spatial patterns of plant chemical traits86.

It is important to note that our study focused specifically on nepetalactone concentration as a response variable. Although absolute essential oil concentration was not measured, numerous ecological and phytochemical studies recognize compound concentration as a valid proxy for assessing biosynthetic responses to environmental gradients, especially when coupled with spatial and statistical modeling frameworks87.

The observed spatial heterogeneity in predicted habitat suitability, while presented cautiously in the results, corresponds with known ecological preferences of N. persica, particularly the species’ association with mid-elevation zones, favorable slope exposures, and optimal temperature regimes. These patterns align with ecological theories of plant chemical defense optimization, where moderate abiotic stress stimulates secondary metabolite production, whereas excessive stress can suppress biosynthesis or compromise plant fitness88,89.

The present study contributes to a growing body of research advocating for the integration of advanced machine-learning approaches in plant ecological studies. By elucidating the environmental drivers of nepetalactone variability, our findings provide a scientific basis for future research on the adaptive strategies of N. persica and related taxa. Moreover, understanding the spatial patterns of bioactive compound accumulation is crucial for both conservation efforts and the potential optimization of medicinal plant resources in response to environmental change.

Future studies should incorporate additional physiological, biochemical, and yield-related data, including essential oil content and seasonal metabolite dynamics, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of plant-environment interactions. Furthermore, the integration of high-resolution climatic variables, such as maximum and minimum temperatures or precipitation seasonality, may enhance the predictive power of ecological models and better capture the environmental complexity influencing secondary metabolite production.

Conclusion

This study provided an integrative framework for the sustainable cultivation and conservation of N. persica, a medicinal species of critical pharmacological and ecological value. By rigorously identifying elevation, south-facing slopes, and moderate temperatures as primary determinants of nepetalactone biosynthesis, our findings established actionable criteria for precision agriculture in semi-arid regions. These insights empower farmers and agronomists to leverage high-resolution topographic maps and climate data for optimizing cultivation practices, which could possibly improve concentrations by up to 40%, considering the spatial variability noted in metabolite concentrations, while simultaneously minimizing resource waste—an essential advantage in water-scarce landscapes. Beyond agricultural applications, this research offered far-reaching implications for biodiversity conservation and climate resilience strategies. In the face of habitat fragmentation and climate-induced range shifts, our findings provided an evidence-based foundation for conservation planning. By identifying the most suitable environmental conditions for N. persica, conservationists can design climate-resilient protected areas that prioritize mid-elevation regions with optimal temperature gradients. This approach aligns directly with global biodiversity preservation efforts, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 13 (Climate Action) and 15 (Life on Land), reinforcing the critical role of ecological data in shaping proactive land management policies. Moreover, the methodological framework adopted in this study—integrating machine learning, geospatial analytics, and phytochemical profiling—established a replicable model for optimizing secondary metabolite production in other medicinal plant species. Unlike traditional habitat suitability models that focus solely on species presence, this approach prioritizes metabolite-driven habitat optimization, offering pharmaceutical industries a targeted strategy for sourcing raw materials from regions with superior environmental and genetic profiles. In summary, this research did not merely describe ecological patterns—it equipped stakeholders with science-driven tools to revolutionize medicinal plant management. From precision agriculture to climate adaptation policies, the implications are profound, ensuring that N. persica thrives as both a keystone species in fragile ecosystems and a sustainable source of next-generation therapeutics. The integration of machine learning with ecological modeling marks a significant leap toward bridging the gap between environmental science and industrial application, paving the way for sustainable and high-concentration cultivation of medicinal plants in under dynamic climatic and land-use conditions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Zamani, M., Sonboli, A., Goldansaz, M. & Mirjalili, M. H. In vitro micropropagation and conservation of endangered medicinal plant Nepeta Asterotricha rech. f.(Lamiaceae): genetic fidelity, phytochemical and biological assessment. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 30, 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-024-01416-x (2024).

Naseem, N. et al. An overview on Pharmacological significance, phytochemical potential, traditional importance and conservation strategies of Dioscorea deltoidea: A high valued endangered medicinal plant. Heliyon 10, e31245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31245 (2024).

Lomartire, S. et al. Environmental impact on seaweed phenolic production and activity: an important step for compound exploitation. Mar. Drugs. 19, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19050245 (2021).

Ni, M. et al. New macrocyclic analogs of the natural histone deacetylase inhibitor FK228; design, synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23, 6785–6793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2015.10.004 (2015).

Yadav, D. K., Rathee, S., Sharma, V. & Patil, U. K. A comprehensive review on insect repellent agents: medicinal plants and synthetic compounds. Anti-Inflammatory Anti-Allergy Agents Med. Chem. Doi. https://doi.org/10.2174/0118715230322355240903072704 (2024).

Wojtunik-Kulesza, K., Rudkowska, M., Kasprzak-Drozd, K., Oniszczuk, A. & Borowicz-Reutt, K. Activity of selected group of monoterpenes in alzheimer’s disease symptoms in experimental model studies—A non-systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147366 (2021).

Rascón-Cruz, Q. et al. Antioxidant potential of lactoferrin and its protective effect on health: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26010125 (2024).

Zhang, H. & Wang, L. Analysis of the variation in potential evapotranspiration and surface wet conditions in the Hancang river basin, China. Sci. Rep. 11, 8607. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88162-2 (2021).

Wu, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, H., Wang, W. & Han, S. Shelterbelt Poplar forests induced soil changes in deep soil profiles and climates contributed their Inter-site variations in dryland regions, Northeastern China. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00220 (2019).

Dastgheyb Shirazi, S. S. et al. Moderate grazing is the best measure to achieve the optimal conservation and soil resource utilization (case study: Bozdaghin rangelands, North khorasan, Iran). Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-09334-1 (2021).

Vigricas, E. et al. Total soil CO₂ efflux from drained Terric histosols. Plants 13, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13010139 (2024).

Gxasheka, M., Gajana, C. S. & Dlamini, P. The role of topographic and soil factors on Woody plant encroachment in mountainous rangelands: A mini literature review. Heliyon 9, e20615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20615 (2023).

Jaywant, S. A. & Arif, K. M. Remote sensing techniques for water quality monitoring: A review. Sensors 24, 8041. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24248041 (2024).

Johnson, S. N. et al. Climatic drivers of silicon accumulation in a model grass operate in low- but not high-silicon soils. Plants 12, 995 https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12050995 (2023).

Thakur, M. K., Kumar, T. V. L., Koteswara Rao, K., Barbosa, H. & Rao, V. B. A new perspective in Understanding rainfall from satellites over a complex topographic region of India. Sci. Rep. 9, 15610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52075-y (2019).

Pipia, L. et al. Mapping and cloud Gap-Filling using Gaussian process regression in Google Earth engine. Remote Sens. 13, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13030403 (2021).

Andreadis, K. M. et al. The regional hydrologic extremes assessment system: A software framework for hydrologic modeling and data assimilation. PLoS One. 12, e0176506. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176506 (2017).

Agravat, P. et al. Molluscan marvels of gujarat: exploring species distribution and conservation strategies using a Spatial approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-025-35959-7 (2025).

Bald, L. et al. The devil is in the detail: environmental variables frequently used for habitat suitability modeling lack information for forest-dwelling bats in Germany. Ecol. Evol. 14, e11571. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11571 (2024).

Rather, T. A., Kumar, S. & Khan, J. A. Multi-scale habitat modelling and predicting change in the distribution of tiger and Leopard using random forest algorithm. Sci. Rep. 10, 11473. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68167-z (2020).

Liu, F. et al. Interpretable machine Learning-Based influence factor identification for 3D printing Process-Structure linkages. Polymers 16, 2680. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16182680 (2024).

Kigo, S. N., Omondi, E. O. & Omolo, B. O. Assessing predictive performance of supervised machine learning algorithms for a diamond pricing model. Sci. Rep. 13, 17315. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44326-w (2023).

Li, J., Ai, P., Xiong, C. & Song, Y. Coupled intelligent prediction model for medium- to long-term runoff based on teleconnection factors selection and spatial-temporal analysis. PLoS One. 19, e0313871. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0313871 (2024).

Drake, J. M., Randin, C. & Guisan, A. Modelling ecological niches with support vector machines. J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 424–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01141.x (2006).

Elith, J., Leathwick, J. R. & Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01390.x (2008).

Araújo, M. B. & New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.010 (2007).

Nabati, J., Nezami, A., Neamatollahi, E. & Akbari, M. GIS-based agro-ecological zoning for crop suitability using fuzzy inference system in semi-arid regions. Ecol. Indic. 117, 106646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106646 (2020).

Narouei, M., Javadi, S. A., Khodagholi, M., Jafari, M. & Azizinejad, R. Modeling the effects of climate change on the potential distribution of the rangeland species Gymnocarpus decander Forssk (case study: arid region of southeastern Iran). Environ. Monit. Assess. 194, 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-09657-z (2021).

Kafash, A. et al. Reptile species richness associated to ecological and historical variables in Iran. Sci. Rep. 10, 18167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74867-3 (2020).

Jalali, M. & Jalali, M. Relation between various soil phosphorus extraction methods and sorption parameters in calcareous soils with different texture. Sci. Total Environ. 566–567, 1080–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.133 (2016).

Brinkerhoff, C. B. et al. Ephemeral stream water contributions to united States drainage networks. Science 384, 1476–1482. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg9430 (2024).

Verma, N. & Shukla, S. Impact of various factors responsible for fluctuation in plant secondary metabolites. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmap.2015.09.002 (2015).

Akula, R. & Ravishankar, G. A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant. Signal. Behav. 6, 1720–1731. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.6.11.17613 (2011).

Neissi, L., Golabi, M. & Gorman, J. M. Spatial interpolation of sodium absorption ratio: A study combining a decision tree model and GIS. Ecol. Indic. 117, 106611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106611 (2020).

Osborne, B. B. et al. Biogeochemical and ecosystem properties in three adjacent semi-arid grasslands are resistant to nitrogen deposition but sensitive to edaphic variability. J. Ecol. 110, 1615–1631. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13896 (2022).

Momtazi, A. A. et al. Phytochemical analysis and cytotoxicity evaluation of Kelussia odoratissima Mozaff. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 10, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jams.2017.02.002 (2017).

Rigano, F. et al. Nano liquid chromatography directly coupled to electron ionization mass spectrometry for free fatty acid Elucidation in mussel. Anal. Chem. 88 (1), 4021–4028. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00328 (2016).

Yang, Z. et al. Disentangling the effects of species interactions and environmental factors on the Spatial pattern and coexistence of two congeneric Pinus species in a transitional Climatic zone. Ecol. Evol. 12, e9275. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9275 (2022).

Al-Hashemi, H. M. B. et al. The validity of laser diffraction system to reproduce hydrometer results for grain size analysis in geotechnical applications. PLoS ONE. 16, e0245452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245452 (2021).

De Coninck, V. et al. Evaluation of a portable urinary pH meter and reagent strips. J. Endourol. 32, 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2018.0202 (2018).

Di Marzo, L., Pranata, J. & Barbano, D. M. Measurement of casein in milk by Kjeldahl and sodium Dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Dairy. Sci. 104, 7448–7456. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-18794 (2021).

Tolesa, L. D., Gupta, B. S. & Lee, M. J. Chitin and Chitosan production from shrimp shells using ammonium-based ionic liquids. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 130, 818–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.018 (2019).

He, J. et al. Dynamics of phosphorus content in the Water-Sediment interface of wetlands in a Mid-Temperature steppe. Water Environ. Res. 90, 697–705. https://doi.org/10.2175/106143017X14902968254601 (2018).

de Santana, F. B., de Souza, A. M. & Poppi, R. J. Green methodology for soil organic matter analysis using a National near infrared spectral library in tandem with learning machine. Sci. Total Environ. 658, 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.263 (2019).

Li, X., Wang, X., Zhao, Q., Zhang, Y. & Zhou, Q. Situ representation of soil/sediment conductivity using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Sensors 16, 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/s16050625 (2016).

Ouabo, R. E., Sangodoyin, A. Y. & Ogundiran, M. B. Assessment of ordinary kriging and inverse distance weighting methods for modeling chromium and cadmium soil pollution in E-Waste sites in douala, Cameroon. J. Health Pollut. 10, 200605. https://doi.org/10.5696/2156-9614-10.26.200605 (2020).

Li, J. & Heap, A. D. A review of Spatial interpolation methods for environmental scientists. Geosci. Aust. https://ecat.ga.gov.au/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/75831 (2008).

Johnston, K., Ver Hoef, J. M., Krivoruchko, K. & Lucas, N. Using ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst. https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-geostatistical-analyst/overview (Esri, 2001).

Raab, G. et al. Contrasting soil dynamics in a formerly glaciated and non-glaciated mediterranean mountain plateau (Serra Da estrela, Portugal). Catena 215, 106314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106314 (2022).

Roupioz et al. Multi-source datasets acquired over Toulouse (France) in 2021 for urban microclimate studies during the CAMCATT/AI4GEO field campaign. Data Brief. 48, 109109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2023.109109 (2023).

Munawar, M., McNeil, R., Jani, R., Buya, S. & Tarmizi, T. Variations in land surface temperature increase in South-East Asian cities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197, 190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-13604-z (2025).

Xue, J. et al. Sharpening ECOSTRESS and VIIRS land surface temperature using harmonized Landsat-Sentinel surface reflectances. Remote Sens. Environ. 251, 112055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.112055 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. The Spatial variation of hydrological conditions and their impact on wetland vegetation in connected floodplain wetlands: Dongting lake 1 basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 31, 8483–8498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31673-4 (2024).

Chu, H. J. et al. Multi-Parameter relief map from High-Resolution dems: A case study of mudstone Badland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16, 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071109 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Darst, B. F., Malecki, K. C. & Engelman, C. D. Using recursive feature elimination in random forest to account for correlated variables in high dimensional data. BMC Genet. 19, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-018-0633-8 (2018).

Adler, A. I. & Painsky, A. Feature importance in gradient boosting trees with cross-validation feature selection. Entropy 24, 687 https://doi.org/10.3390/e24050687 (2022).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov Data Min. 785–794 https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (2016).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994018 (1995).

Dastres, E. et al. Harnessing machine learning to predict habitat suitability of medicinal plants: insights from Oliveria decumbens under environmental change. Spat. Inf. Res. 33, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-025-00629-w (2025).

Wen, B. et al. Multimodal MRI radiomics-based stacking ensemble learning model with automatic segmentation for prognostic prediction of HIFU ablation of uterine fibroids: a multicenter study. Front. Physiol. 15, 1507986. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1507986 (2024).

Suh, H. Y. et al. Predicting soft tissue changes after orthognathic surgery: the sparse partial least squares method. Angle Orthod. 89, 910–916. https://doi.org/10.2319/120518-851.1 (2019).

Fuadah, Y. N., Pramudito, M. A. & Lim, K. M. An optimal approach for heart sound classification using grid search in hyperparameter optimization of machine learning. Bioengineering 10, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10010045 (2022).

Wurm, M. J. & Rathouz, P. J. Semiparametric generalized linear models with the gldrm package. R J. 10, 288–307 (2018).

Adeyeye, O. A. et al. Integrating partial least square structural equation modelling and machine learning for causal exploration of environmental phenomena. Environ. Res. 274, 121358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2025.121358 (2025).

Correia, H. E. & Abebe, A. Capturing Spatiotemporal dynamics of Alaskan groundfish catch using signed-rank Estimation for varying coefficient models. J. Appl. Stat. 49, 2137–2156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2021.1889996 (2021).

Chen, Y. M., Weng, Y. T., Dong, X. & Tsong, Y. Wald tests for variance-adjusted equivalence assessment with normal endpoints. J. Biopharm. Stat. 27, 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10543406.2016.1265542 (2017).

Rodríguez-Pérez, J., Viruel, E. & Masiá, F. J. Machine learning in habitat suitability modeling for biodiversity conservation: A review. Ecol. Inf. 70, 101698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101698 (2022).

Dastres, E., Esmaeili, H. & Edalat, M. Species distribution modeling of Malva neglecta wallr. Weed using ten different machine learning algorithms: an approach to site-specific Weed management (SSWM). Eur. J. Agron. 167, 127579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2025.127579 (2025).

Dastres, E., Sarvestani, G. S., Edalat, M. & Pourghasemi, H. R. Habitat suitability modeling of dominant weed in Canola (Brassica napus) fields using machine learning techniques. Weed Sci. 73, e35. https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2025.5 (2025).

Dastres, E. et al. Modeling habitat suitability for endangered herb (Salvia leriifolia Benth) using innovative hybrid machine learning algorithms. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 100694 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2025.100694 (2025).

Zhou, Z. H. Ensemble Methods: Foundations and Algorithms (CRC, 2025).

Gershenzon, J. & Dudareva, N. The function of terpenoid natural products in the natural world. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2007.3 (2007).

Petrović, L. et al. Molecular background of the diverse metabolic profiles in leaves and inflorescences of naked catmint (Nepeta Nuda L). Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1452804. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1452804 (2024).

Dastres, E. et al. An evaluation of alternative statistical models for predicting habitat suitability for weeds. Weed Res. 62, 404–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12553 (2022).

Mithöfer, A. & Boland, W. Plant defense against herbivores: chemical aspects. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 63, 431–450. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103854 (2012).

Angst, G. et al. Preferential degradation of leaf-vs. root-derived organic carbon in earthworm-affected soil. Geoderma 372, 114391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114391 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Response of plant secondary metabolites to environmental factors. Molecules 23, 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23030762 (2022).

Nunes, A. et al. Local topographic and edaphic factors largely predict shrub encroachment in mediterranean drylands. Sci. Total Environ. 657, 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.475 (2019).

Wu, R., Lev-Yadun, S., Sun, L., Sun, H. & Song, B. Higher elevations tend to have higher proportion of plant species with glandular trichomes. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 632464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.632464 (2021).

Song, Y. et al. UV-B induces the expression of flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) calli. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1079087. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1079087 (2022).

Zheng, G. et al. Grayanane diterpenoid glucosides as potent analgesics from Pieris Japonica. Phytochemistry 171, 112234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112234 (2020).

Pereira, E. et al. Effects of gamma radiation on the bioactivity of medicinal and aromatic plants: Mentha × Piperita L., Thymus vulgaris L. and Aloysia Citrodora Paláu as case studies. Food Funct. 9, 5150–5161. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8fo01558a (2018).

Chrysargyris, A. et al. Phytochemical profiles and biological activities of plant extracts from aromatic plants cultivated in Cyprus. Biology 13, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13010045 (2024).

von Biela, V. R. et al. Differential heat shock protein responses in two species of Pacific salmon and their utility in identifying heat stress. Conserv. Physiol. 11, coad092. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/coad092 (2023).

Dastres, E. et al. Habitat suitability modeling of Descurainia Sophia medicinal plant using three bivariate models. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195, 392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-10996-2 (2023).

Afkar, S. & Karimzadeh, G. Changes in physiological traits, gene expression and phytochemical profile of mentha Piperita in response to elicitor. Biochem. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-024-10805-6 (2024).

Khan, N. et al. Climate and soil factors co-derive the functional traits variations in naturalized downy Thorn Apple (Datura innoxia Mill.) along the altitudinal gradient in the semi-arid environment. Heliyon 10, e27811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27811 (2024).

Tan, K. et al. The discontinuous elevational distribution of an ungulate at the regional scale: implications for speciation and conservation. Animals 11, 3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11123565 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No. 4029591. The authors would like to thank the late Erfan Dastres for his assistance in collecting the samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Emran Dastres: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. Ali Sonboli: Supervision, Validation, Investigation, Writing—review and editing. Hassan Esmaeili: Formal analysis, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—review and editing. Mohammad Hossein Mirjalili: Validation, Investigation, Writing—review and editing. Mohsen Edalat: Validation, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions