Abstract

This study presents the SHGBA framework, integrating a modified Bat Algorithm (BA) with the Second Horizontal Gradient (SHG) technique to enhance geothermal reservoir characterization through self-potential (SP) data inversion. The SHGBA approach leverages SHG’s ability to suppress regional effects and BA’s global search to precisely estimate subsurface parameters like amplitude coefficient (K), depth (z), location (xo), shape factor (q), and polarization angle (Ɵ). Unlike conventional SP inversion approaches, SHGBA refines SHG-derived anomalies using BA’s global optimization, reducing noise and improving accuracy in geothermal modeling with minimal reliance on prior assumptions. Tested on synthetic models under noise-free and noisy (5% and 10%) conditions, as well as multi-source models with overlapping anomalies, SHGBA consistently recovered parameters, proving its robustness. When applied SP data from Hi’iaka dike surveys (1973–2012) at Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii, SHGBA successively characterized basaltic dike intrusion parameters and tracked temporal thermal changes. Unlike traditional techniques prone to local minima and reliant extensive prior assumptions, SHGBA’s population-based optimization thoroughly explores parameter space, excelling in nonlinear and multi-parameters SP inversion. Requiring minimal prior constraints, SHGBA is well-suited for geothermal exploration, volcanic monitoring, and reservoir management, enhancing drilling efficiency, monitoring, and sustainable geothermal energy production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The self-potential (SP) method, a passive geophysical technique, measures natural electrical potential differences on Earth’s surface, driven by electrokinetic, electrochemical, and thermoelectric processes. These measurements reveal subsurface structures and geodynamic processes, making SP a valuable for geothermal exploration1,2,3,4. SP anomalies highlight fluid flow, permeability contrasts, or temperature gradients, key for characterizing geothermal reservoirs5,6,7,8. Advanced SP data interpretation methods enhances resource development and supports global energy sustainability9,10.

Traditional SP data interpretation uses forward modeling, iteratively adjusting synthetic models to match observed data11,12but it’s computationally intensive and yields non-unique solutions13,14. Least-squares inversion is efficient but noise-sensitive, frequently converging to local minima with ambiguous results15,16. Advanced inverse modeling techniques estimate subsurface parameters directly from SP anomalies17. Metaheuristic algorithms like Genetic Algorithms (GA)18,19Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)20,21,22,23and Differential Evolution (DE)24excel in complex solution spaces but need careful parameter tuning and may face slow convergence or premature stagnation25.

The Bat Algorithm (BA), inspired by bat echolocation, is a robust metaheuristic for geophysical inversion26,27balancing global exploration and local exploitation for rapid convergence with minimal local minima. In SP data interpretation, BA excels at estimating subsurface parameters like depth, amplitude coefficient, and shape factor28,29. Isolating target anomalies from regional effects remains challenging. The Horizontal Gradient (HG) method enhances anomaly edges30,31. The First Horizontal Gradient (FHG) removes zero-order regional trends to detect shallow structures but struggles with higher-order effects32. The Second Horizontal Gradient (SHG) mitigates first-order regional trends, clarifying target anomalies33,34.

The SHGBA framework combines the SHG with BA to advance SP data interpretation for geothermal exploration. SHG uses variable window sizes to suppress first-order regional effects, enhancing target anomaly detection. BA inverts the processed data to estimate subsurface parameters, excelling in high-dimensional search spaces. This hybrid approach improves the accuracy and reliability of subsurface modeling for complex geothermal reservoirs with simple geometric shapes like spheres and cylinders.

The SHGBA framework enhances geothermal energy development by improving resource assessment, reducing exploration costs, and boosting energy extraction efficiency. It precisely identifies and characterizes geothermal anomalies, enabling accurate reservoir boundary delineation for better exploration decisions35. This reduces drilling needs, lowering costs and environmental impact. Accurate subsurface modeling optimizes well placement and reservoir management, increasing energy output10. SHGBA supports energy conservation and sustainability by promoting efficient resource use and reducing fossil fuel reliance, strengthening geothermal energy’s role in the global mix9.

This study tests the SHGBA methodology on synthetic and real SP datasets, including a periodic field dataset from the Hi’iaka dike, Kilauea, USA. Results show enhanced precision in modeling geothermal reservoirs, highlighting the value of hybrid optimization in geophysical exploration for renewable energy. The paper is structured as follows: the methodology section explains BA and SHG integration for SP data inversion, the results and discussion section covers findings from synthetic and field datasets, and the conclusion summarizes effectiveness and suggests future research directions.

Methodology for geothermal energy resource assessment

This study introduces a methodology for assessing geothermal energy resources, emphasizing sustainable energy management through geophysical modeling and optimization. It combines SP data forward modeling, adaptive SHD computation, and BA for parameters estimation in geothermal reservoir characterization, aiding drilling, reservoir management, and monitoring technologies.

Forward modeling of self-potential data

The first phase involves generating synthetic SP data for idealized subsurface geometries, including spherical, cylindrical, and prismatic models, to simulate geothermal reservoirs. These models, illustrated in Fig. 1, incorporate key subsurface parameters such as depth, location, and polarization characteristics. The forward modeling employs the following equation to produce synthetic datasets for single and multiple reservoir scenarios36,37,38,39:

The residual data can be defined by the following equation:

The regional data defined by the first order polynomial equation:

By substituting the (Eqs. 2, 3) into (Eq. 1), so we can generate the total self-potential data for the synthetic examples.

where n represents the number of data points \(\:{x}_{j}\) denotes the profile measurement positions, \(\:{x}_{o}\) indicates the source origin point (in meters), z is the depth of the buried source (in meters), q is the dimensionless shape factor defining the geometry of the body (dimensionless), K is the amplitude coefficient (in mV.\(\:{m}^{2q-1}\)), Ɵ represents the polarization angle (in degrees), A & B are constants of the regional polynomial equation and \(\:{SP}_{total}\) is the observed self-potential data, comprising \(\:{SP}_{regional}\) the regional data and \(\:{SP}_{residual}\) the residual data, demonstrating the method’s capability to handle real-world data.

Horizontal gradient with variable window lengths

Enhancing anomaly edges in SP data interpretation requires suppressing regional effects that obscure subsurface structures. The Horizontal Gradient (HG) method highlights lateral variations through spatial derivatives. The FHG removes zero-order regional trends to delineate shallow structures32 but struggles with higher-order effects, leaving residual background noise. The SHG mitigates first-order regional trends, isolating localized anomalies33. Window length in SHG calculations affects regional suppression and resolution, so multiple window sizes are used to generate varied SHG anomalies34improving detection subsurface structures relevant to geothermal drilling and monitoring.

The FHG is calculated using variable window length s by (Eq. 4), while the SHG is computed using Eq. (5), which adapts to diverse geological conditions with higher-order of regional data. The gradients at observation points xj are expressed as:

where s = 1, 2, 3, …, M denotes the window lengths.

Selecting appropriate window lengths s in the SHG method plays a vital role in balancing the removal of regional trends with the ability to resolve fine-scale features. In this study, we employ a series of 10 different window sizes, from 1 to 10 m, to capture anomalies across a broad range of spatial scales and depths. This interval was chosen to align with the spatial resolution of our dataset and the anticipated geometric characteristics of the subsurface sources. Shorter window lengths are more responsive to near-surface and smaller anomalies, while longer ones better reveal deeper or more extensive structures by minimizing short-wavelength noise. This scale-adaptive approach strengthens the clarity of structural boundaries, which is crucial for geothermal exploration. Each SHG output, corresponding to a specific window length, is analyzed using the Bat Algorithm (BA) to infer source parameters. The final interpretation is refined by averaging results from all window scales, thereby enhancing the reliability and consistency of the inversion.

Bat Algorithm (BA)

The BA, introduced by Yang26is a bio-inspired metaheuristic optimization technique based on bat echolocation. Bats employ echolocation to navigate, locate colonies, avoid obstacles, and track prey, emitting 8–10 kHz sound pulses lasting milliseconds. As they near targets, pulse rate increases and echo amplitude decreases26. BA mathematically mimics this to optimize objective functions, with bats using sonar for distance measurement, operating in a frequency range [Cmin, Cmax], with initial velocity (Li) at position (Bi), and dynamically adjusting pulse emission rate (Ri) and loudness (Ui) based on target proximity.

Through testing various configurations on a noise-free synthetic model, an optimal frequency range of 0–5 Hz was identified (Fig. 2). The pulse emission rate, Ri varies between 0 (no emission) and 1 (maximum emission), while the initial loudness, Ui, typically ranges between 1 and 226. Frequency or wavelength adjustments influences the bats’ exploration range, making the selection of an appropriate frequency critical to align with the region of interest before adapting to spatial constraints. When a new solution is found, BA updates the pulse emission rate and loudness, reflecting the selection of the best solution28,40,41.

The convergence behavior and rate of BA was evaluated on synthetic datasets from Model 1 (Fig. 2) using a comprehensive set parameter bounds, including frequency (Ci), loudness (Ui), and pulse emission rate (Ri). The configuration C1= [0, 5], U1 = 1, and R1 = 0.9 yielded the fastest convergence and the lowest normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE). Detailed algorithmic implementation, including equations governing frequency, velocity, and position updates, as well as adaptive control of loudness and pulse emission rates, is provided in Appendix A.

The initial ranges for model parameters such as source depth (z), amplitude (K), and location (\(\:{x}_{o}\)) were selected based on physical feasibility and anomaly size in the synthetic setup. Broad initial bounds (e.g., z ∈ [1, 20] m) were refined after exploratory runs to focus the search on regions where consistent convergence was observed. This adaptive strategy improved both accuracy and efficiency of the BA-based inversion. When convergence stagnated or failed, the search space was re-expanded to ensure that the global optimum could still be located.

Integrated SHGBA framework for geothermal reservoir characterization

The SHGBA framework integrates SHG anomalies with an enhanced BA to improve subsurface parameter estimation for geothermal energy resources, targeting depth (z), horizontal location (\(\:{x}_{o}\)), geometric shape factor (q), amplitude coefficient (K), and polarization angle (Ɵ). It supports sustainable geothermal energy management by providing precise insights for drilling, reservoir management, and monitoring. BA iteratively explores the search space, minimizing misfit between observed and calculated SP anomalies. The search space is defined by the selection of parameters bounds and we employ broad bounds to ensure that the global optimum lies within the search space and to avoid premature convergence, once we get a consistent range where optimal or near optimal solutions were located, then we refined the bounds accordingly. This step helps in accelerating the convergence and improve computational efficiency.

Bats navigate the multidimensional space randomly, refining solutions based on performance, with the lowest misfit solution designated as the global best position, \(\:{B}_{best}\), retained after each iteration until convergence. SHGBA was tested on synthetic datasets for reliability before field data application, validating its efficacy for geothermal exploration.

The process commences with extracting SHG anomalies from SP data using multiple window sizes to detect anomalies across scales and isolate geothermal reservoir signatures from regional effects. Each SHG anomaly feeds into BA, which estimates subsurface parameters by simulating bats adjusting position via echolocation- inspired mechanisms. The best solution per iteration minimizes the objective function, updating \(\:{B}_{best}\:\)until convergence. Statistical averaging of parameter estimates from multiple SHG anomalies enhances robustness, reducing uncertainties from noise or localized anomalies for reliable subsurface characterization critical for geothermal management and geophysical exploration. The workflow is shown in Fig. 3.

The inversion accuracy was assessed using normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE)–based objective function (\(\:{V}_{Obj}\)). This metric evaluates the discrepancy between observed and modeled SP data as follows:

where N is the number of data points, \(\:{SP}_{total}\) represents the observed SP data, and \(\:{SP}_{calculated}\:\)denotes the modeled SP data. This objective function (Eq. 6) is utilized to assess misfit values for all solutions, with the bat achieving the lowest misfit is selected as the global best solution \(\:{B}_{best}\).

The SHGBA framework enhances geothermal energy technologies with precise subsurface parameter estimates, optimizing drilling, reservoir management, and real-time monitoring. Multi-scale SHG analysis refines reservoir boundary delineation, reducing exploration costs and environmental impact. BA’s adaptive optimization ensures reliable parameter estimation, supporting sustainable reservoir management by minimizing energy waste and optimizing resource extraction. The workflow, illustrated in Fig. 3, highlights its role in geothermal and global sustainability goals.

Results and discussion

Evaluation using synthetic datasets

The SHGBA framework was rigorously tested for robustness and accuracy in inverting SP data for geothermal reservoir characterization. Synthetic datasets, simulating real-world complexities, were used to assess performance across diverse scenarios, supporting geothermal exploration and sustainable resource management.

Model 1: robustness under varying noise levels with first-order regional effects

To evaluate the efficacy of the SHGBA framework in geothermal reservoir characterization, synthetic SP anomaly was generated using Eq. (1) with the following parameters: K = 800 \(\:\text{m}\text{V}.\text{m}\), z = 5 \(\:\text{m}\), xo = 0 \(\:\text{m}\), q = 1, and Ɵ = -30° over a 200 m profile, incorporating a first-order regional trend expressed as \(\:0.4\left(x-\:{x}_{o}\right)+60\) (Fig. S1a). The SHGBA was applied to optimize the inversion process by analyzing SHG anomalies across window sizes (s = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 m) (Fig. S1d). The optimization minimized the NRMSE of the objective function. Fig. S1b illustrates the estimated average loudness of the SP data, while Figure S1c shows the optimal pulse emission rate of the bats. Figure S1e depicts the evolution of the minimum NRMSE, converging after approximately 50 iterations for all simulated “microbats” (individual components of SHGBA). Figure S1f shows the average NRMSE per iteration, confirming steady convergence toward the optimal solution. The low NRMSE highlights SHGBA’s ability to accurately recover the original parameters.

Table S1 summarizes the average estimated parameters and their standard deviation from various SHG anomalies: K = 800 ± 8.498 \(\:mV.m\), z = 5 ± 0.17 \(\:m\), xo = 0 ± 0.667 \(\:m\), q = 1 ± 0.075, Ɵ = -30° ± 0.817, characterizing a horizontal cylinder. The NRMSE was \(\:5.24\times\:{10}^{-6}\).

To test robustness, 5% random Gaussian noise was introduced into the synthetic data (Fig. S2). SHGBA successfully recovered parameters by minimizing NRMSE (Fig. S2a). Estimated parameters closely matched the originals: K = 795 ± 9.428 \(\:mV.m\), z = 5.1 ± 0.183 \(\:m\), xo = 0 ± 1.764 \(\:m\), q = 1 ± 0.058, Ɵ = -30˚ ± 1.247, with an The NRMSE of \(\:7.09\times\:{10}^{-5}\) (Table S2).

Figures S2b and S2c show the estimated average loudness and optimal pulse emission rate, respectively, while Fig. S2d illustrates the SHG anomalies for noisy data. Figures S2e and S2f depict the convergence process via minimum and average NRMSE values.

A further test introduced 10% random noise (Fig. S3). SHGBA, maintained robust performance, minimizing NRMSE (Fig. S3a) and yielding parameters: K = 815 ± 25.055 \(\:mV.m\), z = 4.8 ± 0.279 \(\:m\), xo = 0.5 ± 0.527 \(\:m\), q = 1 ± 0.1, Ɵ = -31˚ ± 1.886. The NRMSE was \(\:5.82\times\:{10}^{-5}\) (Table S3). Figures S3b and S3c display the estimated loudness and emission rate, respectively, while Figure S3d shows SHG anomalies. Figures S3e and S3f illustrate convergence through minimum and average NRMSE. Figure S4 presents relative errors for each parameter, demonstrating SHGBA’s accuracy and stability across varying noise levels and supporting it application in geothermal drilling and monitoring.

The SHGBA framework excels in recovering parameters under noisy conditions, enhancing sustainable geothermal energy management. Accurate depth and location estimates optimize drilling, minimizing environmental impact and costs. Its noise robustness ensures reliable reservoir characterization, supporting long-term monitoring and sustainable resource extraction.

Model 2: performance with neighboring anomalies and regional effects

This section evaluates SHGBA’s performance in complex scenarios involving neighboring anomalies and regional effects. A synthetic dataset was generated combining three subsurface models–a horizontal cylinder (K = 3100 \(\:mV.m\), z = 5 \(\:m\), xo = -30 \(\:m\), q = 1, Ɵ = 65˚), a vertical cylinder (K = 850 \(\:mV\), z = 8 \(\:m\), xo = 0 \(\:m\), q = 0.5, Ɵ = 85˚), and a sphere (K = 7500 \(\:mV.{m}^{2}\), z = 4 \(\:m\), xo = 20 \(\:m\), q = 1.5, Ɵ = -45˚)–with a first-order regional trend \(\:0.2\left({x}_{j}-\:{x}_{o}\right)+400\) (Fig. S5a, noise-free; Fig. S6a, 5% noise), calculated using Eq. (1).

SHGBA was applied to estimate parameters using SHG anomalies across window sizes (s = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 m) (Fig. S5d). The results demonstrate effective parameter recovery: horizontal cylinder (K = 3150 ± 39.158 \(\:mV.m\), z = 5.2 ± 0.176 \(\:m\), xo = -30 ± 1.333 \(\:m\), q = 1 ± 0.075, Ɵ = 66˚ ± 2.055), vertical cylinder (K = 850 ± 21.082 \(\:mV\), z = 8 ± 0.163 \(\:m\), xo = 0 ± 1.491 \(\:m\), q = 0.5 ± 0.053, Ɵ = 85˚ ± 1.155), and sphere (K = 7450 ± 57.735 \(\:mV.{m}^{2}\), z = 3.8 ± 0.125 \(\:m\), xo = 21 ± 0.817 \(\:m\), q = 1.5 ± 0.078, Ɵ = -45˚ ± 1.054) (Table S4). The NRMSE was \(\:1.57\times\:{10}^{-5}\), indicating a good fit between the calculated and synthetic anomalies (Fig. S5a). Figures S5b and S5c show estimated loudness and emission rate, respectively, while Figure S5e illustrates NRMSE reduction over approximately 260 iterations, and Figure S5f shows average NRMSE convergence.

With 5% noise, SHGBA yielded: horizontal cylinder (K = 3050 ± 100 \(\:mV.m\), z = 5 ± 0.267 \(\:m\), xo = -30 ± 1.699 \(\:m\), q = 1 ± 0.1, Ɵ = 65˚ ± 1.054), vertical cylinder (K = 880 ± 13.333 \(\:mV\), z = 8.4 ± 0.170 \(\:m\), xo = 1 ± 1.886 \(\:m\), q = 0.51 ± 0.084, Ɵ = 84˚ ± 1.491), and sphere (K = 7520 ± 67.495 \(\:mV.{m}^{2}\), z = 4.2 ± 0.226 \(\:m\), xo = 20 ± 2.160 \(\:m\), q = 1.51 ± 0.074, Ɵ = -43˚ ± 1.764) (Table S5). The NRMSE was \(\:1.01\times\:{10}^{-1}\) (Table S5 and Fig. S6a), indicating a strong correlation between the computed and noisy anomalies. Figures S6b and S6c depict loudness and emission rate, respectively, while Figure S6d shows SHG anomalies. Figure S6e indicates NRMSE convergence after approximately 280 iterations, and Figure S6f confirms average NRMSE trends. Figure S7 illustrates relative errors, highlighting SHGBA’s capability to handle complex geothermal reservoir settings with neighboring structures.

The SHGBA framework demonstrates robustness in recovering parameters under noisy and complex geological settings, enhancing geothermal energy technologies. It improves drilling precision, optimizes reservoir management, and supports reliable monitoring for sustainable energy production. Its ability to interpret data in real-world geothermal fields promotes efficient resource utilization and advances sustainable energy management practices.

Real-world applications

The SHGBA method was rigorously evaluated in real-world geothermal energy applications, emphasizing sustainable energy management through enhanced reservoir characterization. Applied to real datasets, SHGBA accurately delineated subsurface structure under complex conditions, including noise and regional gradients. Its superior parameter estimation enhances geothermal technologies, optimizing drilling, reservoir management, and monitoring in dynamic geological environments like volcanic or geothermal reservoir.

Case study: Hi‘iaka Anomaly, Kilauea Volcano, USA

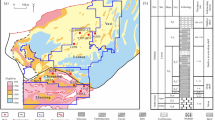

Periodic SP surveys were conducted along the Hi’iaka dike, a basaltic intrusion within the upper East Rift Zone of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii, in 1973, 1995, 1997, and 2012 (Fig. 4). This dike is associated with the eruptive activities of the Hi’iaka and Pauahi craters and is part of the structurally complex Kilauea East Rift Zone, characterized by magma intrusions and dike formations42,43. The intrusion caused a 100-meter-long surface rupture, facilitating magma migration southwest of Hi’iaka Crater. Geophysical studies indicate that the dike expands approximately 1.5 km beneath the surface, trending southwestward (Fig. 4).

Location map of Kīlauea Volcano, Hawai‘i, highlighting the Hi‘iaka region where self-potential (SP) anomaly surveys were conducted. The inset provides a detailed view of the Hi‘iaka area along the Kīlauea rift zone, showing the spatial distribution of SP profiles acquired during multiple survey campaigns in 1973, 1995, 1997, and 2012 (after Tilling et al.43; Davis46.

Initial SP measurements were performed by Zablocki44,45 in 1973, with subsequent surveys in 1995, 1997, and 2012 to monitor temporal variations in SP anomalies, primarily driven by hydrothermal fluid flow and geothermal activity. Previous research suggests that geothermal reservoirs form above dike intrusions, where heat from cooling magma drives hydrothermal circulation, producing hot water and steam viable for geothermal energy46. To ensure consistent interpretation, SP profiles from these years (1973, 1995, 1997, and 2012) were digitized at 10-meter intervals. Earlier studies, such as Davis46applied inversion techniques using a trapezoidal (dike-like) source model, estimating intrusion depths ranging from 50 to 190 m, with increasing depths linked to magma cooling, heat dissipation, and structural changes.

In this study, the SHGBA was applied to analyze SP anomalies from these four survey years to estimate subsurface parameters of the Hi‘iaka dike and assess geometric and geothermal changes over time. The SHGBA integrates SHG analysis with varying window lengths (10 m to 100 m in 10 m increments) and a modified BA to estimate parameters: amplitude coefficient (K), depth (z), source origin (xo), shape factor (q), and polarization angle (Ɵ). The objective function, based on NRMSE, was minimized through iterative optimization. For the 1973 SP profile, the inversion yielded: K = -10,700 \(\:mV\, {m}^{2q-1}\), z = 53 \(\:m\), x₀ = 289 \(\:m\), q = 0.8, Ɵ = -89°, with a NRMSE of 12.372 (Table S6). Figure 5a shows the observed and modeled SP data, with Fig. 5b and c depicting the dynamic evolution of average loudness and pulse emission rate, respectively. SHG anomalies across window lengths are shown in Fig. 5d, while Fig. 5e and f illustrate NRMSE convergence within ~ 10 iterations.

Inversion results for the 1973 SP profile of the Hi‘iaka anomaly. (a) Comparison of observed and modeled SP data alongside derived parameter values by our algorithm and Mehanee et al.8 method. (b) Average loudness variation. (c) Dynamics of plus emission rate. (d) SHG anomalies across varying window sizes. (e) Convergence of NRMSE over iterations. (f) Mean NRMSE per iteration.

For the 1995 SP profile, the inversion produced: K = -10,150 \(\:mV\, {m}^{2q-1}\), z = 58 \(\:m\), x₀ = 281 \(\:m\), q = 0.8, Ɵ = -89°, with a NRSME of 11.532 (Table S7). Figure 6a compares observed and modeled data, with Fig. 6b and c showing loudness and emission rate dynamic. SHG anomalies are presented in Fig. 6d, and Fig. 6e and f confirm convergence within ~ 10 iterations.

Inversion results for the 1995 SP profile of the Hi‘iaka anomaly. (a) Comparison of observed and modeled SP data alongside derived parameter values by our algorithm and Mehanee et al.8 method. (b) Average loudness variation. (c) Dynamics of plus emission rate. (d) SHG anomalies across varying window sizes. (e) Convergence of NRMSE over iterations. (f) Mean NRMSE per iteration.

For the 1997 SP profile, the inversion produced: K = -4550 \(\:mV \, {m}^{2q-1}\), z = 77 \(\:m\), x₀ = 318 \(\:m\), q = 0.7, Ɵ = -108°, with a NRMSE of 10.938 (Table S8). Figure 7a shows the observed and modeled data match, with Fig. 7b and c tracking algorithm’ behavior. SHG anomalies are in Fig. 7d, and Fig. 7e and f depict NRMSE convergence.

Inversion results for the 1997 SP profile of the Hi‘iaka anomaly. (a) Comparison of observed and modeled SP data alongside derived parameter values by our algorithm and Mehanee et al.8 method. (b) Average loudness variation. (c) Dynamics of plus emission rate. (d) SHG anomalies across varying window sizes. (e) Convergence of NRMSE over iterations. (f) Mean NRMSE per iteration.

For the 2012 SP profile, the estimates were: K = -10,150 \(\:mV \, {m}^{2q-1}\), z = 58 \(\:m\), x₀ = 281 \(\:m\), q = 0.8, Ɵ = -89°, with the lowest NRMSE of 10.064 (Table S9). Figure 8a shows strong agreement between observed and modeled data, with Fig. 8b and c illustrating loudness and emission rate trends. SHG anomalies (Fig. 8d) and convergence plots (Fig. 8e and f) confirm rapid optimization within ~ 10 iterations.

Inversion results for the 2012 SP profile of the Hi‘iaka anomaly. (a) Comparison of observed and modeled SP data alongside derived parameter values by our algorithm and Mehanee et al.8 method. (b) Average loudness variation. (c) Dynamics of plus emission rate. (d) SHG anomalies across varying window sizes. (e) Convergence of NRMSE over iterations. (f) Mean NRMSE per iteration.

The consistency between the 1995 and 2012 profiles suggests stabilization of the subsurface structure in later years, while 1973 and 1997 show e variability in depth, shape factor, and strength, likely reflecting changes in thermal regime, fluid dynamics, or cooling. The significant drop in K between 1995 and 1997 may indicate reduced hydrothermal activity or heat dissipation. These temporal variations, captured by SHGBA, highlight its ability to resolve subtle surface changes, supporting precise drilling, reservoir management, and monitoring for sustainable geothermal energy production (Table 1). Table 2 compares these results with prior methodologies, affirming SHGBA’s superior robustness and its potential to enhance geothermal resource exploration and management.

Discussion

The evaluation of the SHGBA using both synthetic and real-world datasets highlights its robustness and precision in characterizing geothermal reservoirs, with significant implications for sustainable energy management. The algorithm’s consistent ability to accurately estimate subsurface thermal parameters under complex conditions, including noise and geological variability, underscores its potential to enhance geothermal energy exploration, reservoir management, and monitoring systems, thereby supporting efficient and sustainable energy production.

Accurate characterization of geothermal reservoirs is essential for optimizing energy extraction and minimizing environmental impacts. SHGBA framework, through its hybrid optimization approach, demonstrates superior capability in delineating subsurface thermal structures. In synthetic models, SHGBA truthfully recovered key parameters such as amplitude coefficient (K), depth (z), source origin (x₀), shape factor (q), and polarization angle (Ɵ) with high accuracy, even under varying noise levels. For example, with 5% random Gaussian noise, SHGBA achieved an NRMSE of 7.09 × 10⁻⁵, reflecting its reliability in parameter estimation even in challenging conditions.

In complex scenarios involving multiple neighboring anomalies and regional effects, SHGBA maintained its robustness, effectively distinguishing between overlapping subsurface features. This precision in modeling allows for targeted drilling strategies, minimizing unnecessary drilling and associated costs. By accurately identifying high-potential zones, SHGBA enhances the efficiency of geothermal energy extraction, supporting the economic viability of geothermal projects and their contribution to sustainable energy systems.

Geothermal exploration faces uncertainties due to complex geological, hydrological, and thermal interactions. Traditional geophysical methods often suffer from ambiguities arising from noise contamination, regional trends, or overlapping anomalies47. SHGBA addresses these challenges through its adaptive optimization, which iteratively converges on precise parameter estimates. This capability reduces exploration uncertainties, enabling more informed decision-making in geothermal project planning.

The application of SHGBA to real-world data from the Hi‘iaka dike at Kilauea Volcano further validates its practical utility. Across multiple survey conducted in 1973, 1995, 1997, and 2012, SHGBA provides consistent parameter estimates, capturing temporal variations in subsurface thermal structures. For example, the inversion results for 1995 and 2012 showed consistent depth estimates (z = 58 m) and polarization angles (Ɵ = -89°), suggesting structural stabilization over time, while variations in 1973 and 1997 reflected evolving thermal regimes. These insights are crucial for long-term reservoir monitoring, enabling operators to optimize extraction strategies and adapt to changing subsurface conditions.

Moreover, SHGBA’s resilience to noise and its capacity to handle complex geological settings reduce the need of extensive field surveys, lowering exploration costs and accelerating project timelines. The algorithm’s rapid convergence–typically within fewer than 50 iterations for synthetic data and about 10 iterations for field cases–demonstrates its computational efficiency, making it suitable for integration into automated monitoring systems. The efficiency streamlines data interpretation and support real-time decision-making, enhancing the operational feasibility of geothermal projects.

The SHGBA framework aligns with the broader goals of sustainable energy management by facilitating the responsible exploitation of geothermal resources. Its ability to provide detailed subsurface models supports the design of efficient extraction systems, minimizing environmental impact. For instance, precise depth and location estimates enable the optimization of well placements, reducing surface disturbances and preserving ecological balance.

Furthermore, SHGBA’s adaptability to various geological contexts makes it a versatile tool in the global pursuit of renewable energy solutions. By improving the reliability of geothermal energy projects, it contributes to the diversification of energy portfolios and the reduction of carbon emissions, aligning with global sustainability goals. The algorithm’s ability to enhance subsurface characterization directly contributes to the scalability of geothermal energy as a clean, renewable resource.

Conclusions

This study presents a novel inversion framework, SHGBA (Second Horizontal Gradient Bat Algorithm), which integrates the second horizontal gradient (SHG) technique with a modified Bat Algorithm (BA) to improve the interpretation of self-potential (SP) anomalies in geothermal energy application. The methodology was developed to address key challenges in SP inversion, including the mitigation of regional thermal gradients, noise mitigation, and precise recovery of subsurface thermal parameters. The effectiveness and robustness of SHGBA were rigorously evaluated through synthetic models and real-world geothermal datasets, demonstrating its potential to advance sustainable energy management through improved geothermal reservoir characterization.

Two synthetic models were employed to evaluate SHGBA’s performance. The first model simulated a single buried source with a first-order regional trend, tested under noise-free conditions and with 5% and 10% random noise. Results demonstrated SHGBA’s ability to accurately recover true parameters with high stability, even under significant noise. The second model involved three adjacent subsurface thermal sources with a linear regional gradient, analyzed in noise-free and 5% noise scenarios. Despite the complexity of overlapping thermal anomalies, SHGBA consistently delineated subsurface structures, affirming its capability to handle intricate geothermal settings.

The algorithm was further applied to field datasets from the Hi‘iaka dike in the Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii, collected between 1973 and 2012. These datasets captured the thermal and geoelectrical response of a basaltic dike intrusion. By processing SHG anomalies across multiple window lengths and optimizing them with the modified BA, multiple parameter estimates were obtained and statistically averaged. This approach reduced inversion uncertainty and enhanced model reliability by accounting for variations in window scale and local effects. Compared to traditional inversion methods, SHGBA offers distinct advantages: the SHG operator effectively suppresses regional thermal gradients, improving anomaly localization, while the modified BA ensure robust global optimization and superior convergence in complex and noisy conditions, outperforming conventional gradient-based and some metaheuristic approaches in accuracy and consistency.

Analysis of the Hi‘iaka SP profiles revealed temporal changes in dike geometry and depth, likely linked to thermal evolution and cooling processes. These insights highlight SHGBA’s capability to resolve dynamic changes in geothermal systems and magmatic intrusions. The framework’s flexibility, noise tolerance, and accuracy make it a valuable tool for a broad range of SP applications.

Finally, The SHGBA framework represents a significant advancement in geothermal reservoir characterization, offering tangible benefits in energy recovery and exploration efficiency. Its robust performance in both synthetic and real-world scenarios demonstrates its potential to transform geothermal energy development. By enhancing subsurface modeling accuracy and minimizing uncertainties, SHGBA facilitates the sustainable and efficient utilization of geothermal resources, contributing to the broader objectives of renewable energy adoption and environmental sustainability.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Revil, A. & Jardani, A. The Self-Potential Method: Theory and Applications in Environmental Geosciences 1st edn (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Eppelbaum, L. V. Review of processing and interpretation of self-potential anomalies: transfer of methodologies developed in magnetic prospecting. Geosciences 11, 194 (2021).

Barde-Cabusson, S., Finizola, A. & Grobbe, N. A practical approach for self-potential data acquisition, processing, and visualization. Interpretation 9, T123–T143 (2021).

Essa, K. S. Self-potential data interpretation utilizing the particle swarm method for the finite 2D inclined dike: mineralized zones delineation. Acta Geod. Geophys. 55, 203–221 (2020).

Corwin, R. F. & Hoover, D. B. The self-potential method in geothermal exploration. Geophysics 44, 226–245 (1979).

Revil, A., Ehouarne, L. & Thyreault, E. Tomography of self-potential anomalies of electrochemical nature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4363–4366 (2001).

Finizola, A. et al. Adventive hydrothermal circulation on stromboli volcano (Aeolian islands, Italy) revealed by geophysical and geochemical approaches: implications for general fluid flow models on volcanoes. J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res. 196, 111119 (2010).

Mehanee, S. A., Essa, K. S., Soliman, K. S. & Diab, Z. E. A fast imaging method for the interpretation of self-potential data with application to geothermal systems and mineral investigation. Sci. Rep. 13, 13548 (2023).

IEA. World energy outlook report. Int. Energy Agency, 396 (2024).

IRENA. Renewable energy statistics 2024. Int. Renew. Energy Agency Abu Dhabi, 285 (2024).

Stoll, J., Bigalke, J. & Grabner, E. W. Electrochemical modelling of self-potential anomalies. Surv. Geophys. 16, 107–120 (1995).

Patella, D. Self-potential global tomography including topographic effects. Geophys. Prospect. 45, 843–863 (1997).

Naudet, V. Les méthodes de résistivité électrique et de potentiel spontané appliquées aux sites contaminés. Géophysique [physics.geo-ph]. Université de droit, d’économie et des sciencesAix-Marseille III, Français. NNT: tel-00007727 (2004).

Biswas, A. & Sharma, S. P. Interpretation of self-potential anomaly over idealized bodies and analysis of ambiguity using very fast simulated annealing global optimization technique. Near Surf. Geophys. 13, 179–195 (2015).

Abdelrahman, E. M. et al. New least-squares a logarithm for model parameters estimation using self-potential anomalies. Comput. Geosci. 34, 1569–1576 (2008).

Biswas, A. A comparative performance of least-square method and very fast simulated annealing global optimization method for interpretation of self-potential anomaly over 2-D inclined sheet type structure. J. Geol. Soc. India. 88, 493–502 (2016).

Rao, K., Jain, S. & Biswas, A. Global optimization for delineation of self-potential anomaly of a 2D inclined plate. Nat. Resour. Res. 30, 175–189 (2021).

Di Maio, R., Rani, P., Piegari, E. & Milano, M. Self-potential data inversion through a genetic-price algorithm. Comput. Geosci. 94, 86–95 (2016).

Göktürkler, G. & Balkaya, Ç. Inversion of self-potential anomalies caused by simple geometry bodies using global optimization algorithms. J. Geophys. Eng. 9, 498–507 (2012).

Eberhart, R. & Kennedy, J. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks. Princeton, NJ, Citeseer 1942–1948 (1995).

Santos, F. A. Inversion of self-potential of idealized bodies’ anomalies using particle swarm optimization. Comput. Geosci. 36, 1185–1190 (2010).

Essa, K. S. A particle swarm optimization method for interpreting self-potential anomalies. J. Geophys. Eng. 16, 463–477 (2019).

Pace, F., Santilano, A. & Godio, A. A. Review of geophysical modeling based on particle swarm optimization. Surv. Geophys. 42, 505–549 (2021).

Sungkono An efficient global optimization method for self potential data inversion using micro-differential evolution. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 129, 178 (2020).

Sungkono & Warnana, D. D. Black hole algorithm for determining model parameter in self-potential data. J. Appl. Geophys. 148, 189–200 (2018).

Yang, X. S. A new metaheuristic bat-inspired algorithm. In Nature Inspired Cooperative Strategies (eds Gon Zalez, J. et al.) Vol. 284, 65–74 (2010).

Yang, X. S. & He, X. Bat algorithm: Literature review and applications. Int. J. Bio-Inspir. Com. 5, 141–149 (2013).

Essa, K. S., Diab, Z. E. & Mehanee, S. A. Self-potential data inversion utilizing the Bat optimizing algorithm (BOA) with various application cases. Acta Geophys. 71, 567–586 (2023).

Ai, H. et al. Global optimization of self-potential anomalies using hunger games search algorithm. Pure Appl. Geophys. 181, 1303–1336 (2024).

Pham, L. T., Eldosouky, A. M., Oksum, E. & Saada, S. A. A new high resolution filter for source edge detection of potential field data. Geocarto Int. 37, 3051–3068 (2020).

Alvandi, A. & Ardestani, V. E. Edge detection of potential field anomalies using the Gompertz function as a high-resolution edge enhancement filter. B Geophys. Oceanogr. 64, 279–300 (2023).

Abdelrahman, E. M., Ammar, A. A., Sharafeldin, S. M. & Hassanein, H. I. Shape and depth solutions from numerical horizontal self-potential gradients. J. Appl. Geophys. 37, 31–43 (1997).

Abdelrahman, E. M. et al. A least-squares minimisation approach to depth determination from numerical second horizontal self-potential anomalies. Explor. Geophys. 40, 214–221 (2009).

Essa, K. S. & Elhussein, M. A new approach for the interpretation of self-potential data by 2-D inclined plate. J. Appl. Geophys. 136, 455–461 (2017).

Gehringer, M. & Loksha, V. Geothermal Handbook: Planning and Financing Power Generation (Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), 2012).

Asfahani, J. & Tlas, M. A constrained nonlinear inversion approach to quantitative interpretation of self-potential anomalies caused by cylinders, spheres and sheet-like structures. Pure Appl. Geophys. 162, 609–624 (2005).

Essa, K. S., Mehanee, S. & Smith, P. A new inversion algorithm for estimating the best fitting parameters of some geometrically simple body from measured self-potential anomalies. Explor. Geophys. 39, 155–163 (2008).

Abdelrahman, E. M. et al. Quantitative interpretation of self-potential anomalies of some simple geometric bodies. Pure Appl. Geophys. 166, 2021–2035 (2009).

Mehanee, S. An efficient regularized inversion approach for self-potential data interpretation of ore exploration using a mix of logarithmic and non-logarithmic model parameters. Ore Geol. Rev. 57, 87–115 (2014).

Fister, I. J., Fister, I. & Yang, X. A hybrid Bat algorithm. Electrotech Rev. 80, 1–7 (2013).

Essa, K. S. et al. A prosperous and thorough analysis of gravity profiles for resources exploration utilizing the metaheuristic Bat algorithm. Sci. Rep. 15, 5000 (2025).

Klein, F. W., Koyanagi, R. Y., Nakata, J. S. & Tanigawa, W. R. The seismicity of Kilauea’s magma system. In Volcanism in Hawaii (eds Decker, R. W.), 1019–1185 (U.S.G.S. Prof. Paper, 1987).

Tilling, R. I. et al. The 1972–1974 Mauna Ulu eruption, Kilauea Volcano: An example of quasi-steady-state magma transfer. In Volcanism in Hawaii (eds Decker, R.W.), 1350 (U.S.G.S. Prof. Paper, 1987).

Zablocki, C. J. Mapping thermal anomalies on an active volcano by the self-potential method, Kilauea, Hawaii. In Proceeding 2nd U.N. Symposium on the Development and Use of Geothermal Resources, 1299–1309 (1975).

Zablocki, C. J. Applications of the VLF induction method for studying some volcanic processes of Kilauea volcano. Hawaii. J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res. 3, 155–195 (1978).

Davis, P. M. Geothermal evolution of an intruded dike in the rift zone of Kilauea volcano, Hawaii from VLF and self-potential measurements. J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res. 302, 64–80 (2015).

Eppelbaum, L. & Khesin, B. Geophysical Studies in the Caucasus 421 (Springer, 2012).

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Prof. Yanlong Kong, Editorial Board Member, and the two capable expert reviewers for their keen interest, valuable comments on the manuscript, and improvements to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors: Writing the original manuscript Draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Figures and Tables preparations. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Essa, K.S., Diab, Z.E., Gomaa, O.A. et al. Enhanced self-potential inversion using a hybrid Second Horizontal Gradient and Bat Algorithm–SHGBA-framework for geothermal reservoir characterization. Sci Rep 15, 40407 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17101-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17101-2