Abstract

The performance of a network primarily depends on the probability of failure occurrence and its availability for various services, such as mitigation, latency gap, and simulations. Frequent faults in the cluster networks may result in task failure related to identifying and detecting these services. Therefore, detecting and classifying such faults and initiating corrective actions is required before they transform into system failure. We present a model that includes feature selection, an attention transformer, and feature transformer for fault classification. Our proposed model deals with tabular data with neural nets. The experimental analysis is carried out on the tabular dataset taken from the Telstra cluster network. The results have been reported, including failure records of service disruption events and total connectivity interruptions. The trace-driven experiments have been observed on the efficacy of our proposed model with an average of accuracy (98.3%), precision (98.3%), recall (97.4%), and F1 score (97.8%). The results validate the research objective to predict the failure occurrence in virtual machines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cloud computing paradigm incorporates different areas such as virtualization, virtual servers, data centers, and utility-based pricing. It brings a unique perspective that enables various processes to be performed more efficiently and cost-effectively. With the underlying virtualization technology in the virtual cloud cluster, the cloud provides consumers to an illusion of limitless resource provisioning elastically. Although cloud computing offers numerous benefits, the increasing complexity, functionality, and utilization of cloud computing produce an increased risk of resource failure1. Breakdown in the cloud can occur as a result of hardware failure, software failure, server overload, network congestion, and various other aspects. The ability of a cluster network application to avoid problems during execution can be quite challenging2,3. Accurate prediction algorithms must be employed to reduce the effects of failure in the cloud4,5. Fault Tolerance (FT) can prevent restarting a Virtual Machine, which saves a lot of money as well as energy. As a result, the researcher has offered various FT procedures to improve the reliability of cloud services. The methodologies rely primarily on redundancy6, replication7, checkpointing8, adaptive framework9, etc.

Meanwhile, two types of FT policies are used for cloud applications, reactive and proactive policies10. These methodologies have a significant impact on the prediction and accuracy of faults. Prediction techniques serve their purpose in numerous sectors, including applications in machine learning. The failure prediction study is being carried out extensively and has caught the interest of researchers11. In contrast, fault classification is critical for the study of faults and the faster restoration of cluster networks12,13,14. In recent years, the research on fault classification algorithms has received a lot of attention. However, most of the work has focused on the fault classification problem in the cluster network. Nowadays, it is necessary to have an effective fault classification algorithm in the cluster network15,16.

In machine learning, classification is predictive modeling where class labels are predicted for a given example in the dataset. The objective of doing classification is to divide the different prediction results into separable classes. Various classification algorithms have been suggested in the literature, and gaining more attention from researchers in the field of classification. AdaBoost classifier17,18 is a mostly used classification algorithm. This algorithm starts by fitting a classifier on the original dataset without preprocessing of data. A classifier starts with random or default settings, analyzes the data, and makes predictions. If the predictions are incorrect, it tweaks its weights slightly to improve accuracy. This adjustment process happens over multiple cycles (or iterations), allowing the model to gradually improve its ability to recognize patterns and make accurate classifications. This permits the future model to focus on tough scenarios. However, the imbalance in the dataset may result in less accurate results. The KNeighborsClassifier19 classification operates by picking the k nearest to the target point. If the data quality is not up to the standards, the predictions might be inaccurate. The Support Vector Classifier (SVC)20 works by identifying the optimal boundary, known as a hyperplane, that separates different classes in the dataset. It does this by finding the “best fit” based on the given data, ensuring maximum separation between categories.

However, while SVC is effective for smaller and moderately sized datasets, it does not scale well for large datasets. This is because the algorithm’s complexity increases significantly with the number of data points, making it computationally expensive and slow when handling vast amounts of information. As a result, alternative models like deep learning or ensemble methods are often preferred for big data applications. Furthermore, the Decision Tree21 implements the tree approach for classification, with the Random Forest22 ensemble model integrating several weak learners to generate a more resilient machine learning model23.

One of the major drawbacks is that the large number of trees generated for creating the ensemble may turn out to be quite slow. Gradient Boosting classifier24 also combines weak models (ensembles) to create a strong-performing model for classification. However, it may emphasize more on outliers so that there may be a false prediction. In the Gaussian Naive Bayes model25, the features are presumed to be unrelated to each other for classification. Logistic Regression uses statistical learning to perform classifications. It presumes linearity between the dependent variable and the independent variable, which may affect the predictions. Further, TabNet is a deep learning architecture that is promisingly used for tabular data. It is an explainable and high-performance tree-based model that is prominent for different applications, namely finance, insurance, and retailer-based applications for detecting frauds, predicting credit scores, and forecasting. It uses sequential attention, a machine learning techniques26 to select the model feature at each step in the model. Even though tabular data is the most common data type used in real-world applications, it is still under-explored for deep learning. The way the deep learning architecture outperforms the large dataset, it is expected to achieve significant performance improvements in the tabular dataset as well. Virtual machine (VM) breakdowns are far more likely in contemporary cloud computing environments due to the increasing complexity of virtualised systems. These failures often lead to monetary losses and interruptions in service, and can be caused by a variety of factors, including hardware failure, network congestion, or system overload. The generalisation and interpretability issues presented by tabular datasets are difficult for traditional machine learning (ML) algorithms to handle. Despite its success in the text and image domains, deep learning (DL) is still not widely used for fault classification tasks using structured tabular data.

For fault classification in virtual machine environments, this research extended the TabNet architecture by integrating a custom decision mask and hierarchical feature extraction pipeline tailored to VM fault severity classification. TabNet is ideally suited for tabular dataset interpretation due to its capacity for sequential attention-driven feature selection. Through extensive testing against eight traditional classifiers, our research shows the architecture’s superiority. We also emphasize the model’s scalability, resilience, and potential for fault prediction in real time in cloud infrastructures at the production level.

The paper is structured as follows: Section “Introduction” introduces fault tolerance and machine learning. Section “Related work” presents related work. Section “Research methodology” details the research approach. Section “Result and discussion” presents results and discussion. Section “Conclusion” concludes with evaluations and future directions.

Related work

With the dynamic nature of the cloud, the likelihood of disaster in the Virtual Machine grows. Numerous FT techniques based on redundancy, checkpoint, Virtual Machine migration, hybrid FT, and adaptive FT, among others, have been proposed to address this problem. A considerable amount of research has been conducted in the area of failure prediction and classification using machine learning and deep learning techniques in a distributed cloud system. Chigurupati et al.27 developed a machine learning technique to predict individual components until failure. It was reported to be a more accurate approach than traditional MTBF. The model was developed to monitor the health of 14 hardware samples and notify them of imminent failure well before the actual failure. The only drawback of this model was that it had not been trained with the real failure data. Therefore, the assurance of predicting failure cannot be accurate, and also, the data was not publicly available. Jain et al.28 proposed knowledge based data processing model. Muchandigona et al.29 presents the financial perspectives for cloud communication.

Deep learning is now widely recognized due to the usage of convoluted structures in real-world datasets. It is widely used for research purposes and in industries to build robust systems. In this, the parameters are tuned using the back-propagation algorithm for the subsequent layers. Deep learning became popular in domains such as text, speech, natural language processing, etc., due to its impact on modern systems30. It is performed by building an architecture of a multi-layered neural network from different inputs to desired outputs. One of the major advantages of such models is the automatic recognition of the best features, eliminating the need for manual intervention. The models can process the data sets and identify the best parameters for the predictions31. Gyoal et al.32 proposed neuro-fuzzy based model for data flux mitigation. Raihan et al.33 presents the details about the external audits.

Alessio et. al34 introduced a fault classification algorithm using machine learning in High Performance Computing systems. This technique operates on the online stream data, thereby providing the opportunity to develop and perform in real-time. A tool fault injection ’FINJ’ is developed to seamlessly integrate with the other injective tools to target specific fault types. The researchers focused on tabular (structured) data, which is widely used in the artificial intelligence domain. However, canonical neural network architectures have been under explored for tabular data comprehension.

An architecture named TabNet was first introduced by Ariket et al.35, which combines an RNN and a CNN to classify tables by type. It has an advantage over state-of-the-art methods specialized for table classification and other deep neural network architectures. TabNet takes raw tabular data to learn a flexible representation, and conventional gradient descent-based optimization is used for training without feature preprocessing. The most general approaches for the tabular dataset are tree-based models. These models efficiently pick global features with significant information gain36. The ensemble is the most common technique for improving the performance of a tree-based model, which reduces the model variance. One of the ensemble approaches, the random forest37, grows many trees using randomly selected features and random subsets of data. The ensemble methods, XGBoost38 and LightGBM39, they first learn the structure of the trees and then update the leaves with real-time streaming data. An approach to overcoming the limitations of decision trees is to incorporate neural networks. The canonical neural network building blocks with the decision trees representation40 produce redundancy in representation and ineffective learning. To overcome this problem, a soft decision tree41 is introduced, which uses differentiable decision functions to construct the trees instead of non-differentiable axis-aligned splits. The capability of auto feature selection is lost by avoiding the axis-aligned splits, which is important to learn from the tabular data. However, a new function is also suggested to simulate the decision trees, which evaluate the efficient possible decisions42. A new deep learning model is suggested, which is based on growing the architecture adaptively from basic blocks43.

Therefore, this paper presents a novel Virtual Machine fault classification model based on a deep learning neural network architecture, specifically tailored for tabular datasets. While deep learning has shown exceptional performance in domains like image and text processing, its application to structured tabular data-especially in the context of fault detection-remains limited. Our proposed model addresses this gap by leveraging the strengths of TabNet, which combines interpretability with performance through attention-driven feature selection. The model is designed for seamless integration into real-world cloud monitoring systems. Its low computational footprint and fast inference make it suitable for both centralized data centers and distributed edge environments. The explainable attention mechanism provides transparency, enabling administrators to quickly understand and respond to fault causes. In our approach, TabNet is employed not only for fault prediction but also for effective feature selection. Its sequential attention mechanism identifies the most significant features at each decision step, enhancing both accuracy and interpretability. The efficacy of our proposed model is validated through comparative analysis with eight traditional machine learning classifiers, consistently outperforming them in precision, recall, and F1-score.

Research methodology

Fault classification is critical for fault analysis and speedy repairment in the cluster network. We have seen multiple algorithms based on deep learning and machine learning have been implemented for fault classification.44. Our approach includes dynamic feature selection, hierarchical decision masking, and attention-based learning for fault classification in its methodology. Therefore, We have enhanced the TabNet architecture and proposed a new architecture for our research work.

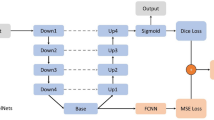

The base architecture

With the advent of deep neural networks, one data type that was still left out to see success was tabular data. Tabular data is considered to be one of the staple data types in the modern world of artificial intelligence45. Several models utilizing the ensemble approach for constructing decision trees have been used extensively for these types of datasets. The deep learning architecture can successfully simulate the decision-making process of a decision tree by dynamically constructing multiple hyperplane decision boundaries at various levels of abstraction. Unlike traditional decision trees, which rely on discrete branching at each node, deep learning models-particularly neural networks-can create continuous, non-linear decision boundaries that evolve as the model learns from data. The best features at each decision step are chosen through sequential attention. Here, the masking of features is done at each step, which helps to identify the best features. It can work directly on the original data without performing much data preprocessing. The research is concluded successfully with the TabNet model surpassing all the baseline classifiers35. TabNet is a deep learning neural network architecture for the classification of tabular datasets. It is also called a Tabular learning model, which can be used on various datasets for classification and regression tasks. As shown in Fig. 1, TabNet uses decision trees through neural network blocks. The most significant features are extracted by using multiplicative sparse masks on the inputs. The extracted features are transformed linearly after the addition of the bias terms to represent the decision boundaries. The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function is employed to refine region selection in the model. It effectively filters out regions by setting negative values to zero, ensuring only positively activated regions contribute to further computations. This characteristic helps in defining distinct decision boundaries by ignoring non-relevant negative regions. Consequently, ReLU enhances the model’s ability to focus on meaningful features while improving computational efficiency46. Finally, the multiple regions are aggregated using addition to obtain the classes used in the classification.

Mathematical function

The proposed model uses sparse feature selection to select only the relevant and non-redundant feature subsets from all the given features. SparseMax normalization promotes sparsity in features by selectively activating only the most relevant ones while suppressing the rest. This is achieved by projecting the input onto a probabilistic simplex, ensuring that only a few features receive significant values. Unlike SoftMax, which assigns small probabilities to all inputs, SparseMax enforces zero activation for less important features. The Euclidean projection method guarantees that the output remains within a valid probability distribution while maintaining sparsity. To compute the Euclidean projection of a point b, where b=\([b_1,...b_D]^T\) \(\in \mathbb {R}^D\) onto our projection simplex, where D is the number of decision steps in the algorithm. It is defined using the following formula:

where a is the unique solution to the problem, which will be denoted by \(a=[a_1,...,a_D]^T\).

The above quadratic equation and the defined objective function will be strictly convex, so there will always exist a unique solution, a. The time complexity of the algorithm that finds the solution a is O(DlogD).

-

1:

Input: \(b \in \mathbb {R}^D\)

-

2:

Sorting b into m such that: \(m_1 \ge m_2 \ge ...m_D\)

-

3:

Find \(\rho =max \left\{ 1\le j\le D: m_j+\frac{1}{j} \left( 1-\sum _{i=1}^{j} m_i\right) <0 \right\}\)

-

4:

Define \(\lambda = \frac{1}{\rho }\{1-\sum _{i=1}^{\rho }\)m\(_i \}\)

-

5:

Output: a \(\ni\) \(a_i\) = \(\text {max}\{b_i+\lambda ,m\},\text {i=1....,D}\)

The cost of sorting the component b of the equation determines the complexity of the algorithm. The active set is determined after D steps as the algorithm is not iterative. Adhering to the standard practice of ensuring the input values are scaled to fall inside the normal distribution, the mean and the standard deviation of the normal distribution are taken as 0 and 1, respectively. In every continuous distribution, there are uncountable infinite sets of values sampled from it. If we assign positive probability to each of the possible values, the probability might sum to infinity, which should not happen. So, the normal distribution is taken to be centered around \(\mu\) (mean of input features), and we can observe most of the samples close to \(\mu\), which rectifies the distribution of our input values. For initialization of the parameters of our neural networks, we use the Xavier initialization, where the parameters are selected randomly from the normal distribution with the mean 0 and standard deviation \(\sigma = \sqrt{\frac{2}{x+y}}\) where x and y are the input and the output weights of the neural network, which makes sure that the optimized weights are identified.

Dataset analysis

To build a trustworthy classification model with better performance accuracy, one should comprehend the dataset and extract the significant features. Therefore, our proposed Virtual Machine fault classification model uses \(severity\_type\) and \(event\_type\) features to leverage the classification.

Dataset exploration

The dataset is provided by the Telstra cluster network47. This dataset includes the failure records of service disruption events that brought momentary glitches or total interruption of connectivity in the Telstra network. The dataset is categorized into five different files as depicted in Table 1, where the main dataset is \(event\_type\). The \(log\_feature\) contains the various features that are extracted from log files. The \(fault\_severity\) in the data set is a target variable, the fault that the users reported in the network. The \(fault\_severity\) is categorized into three different levels, such as 0, 1, 2, which correspond to no fault, only a few, and many faults, respectively. On the other hand, \(severity\_type\) is a warning message extracted from the log files, which is classified into five categories (1-5) in increasing order of severity. All five files are consolidated into a single dataset that includes different types of features such as event type, severity type, resource type, log feature, event count, location, and log volume etc.

The dataset covers more than 7300 failure records, which include \(fault\_severity\) and \(severity\_type\). The dataset corresponding to 0, 1, 2 \(fault\_severity\) contributes 65%, 25%, and 9% of the total dataset, respectively, and the total record counts of events of disruption at each location in the network are shown in Fig. 2. Further, these record counts also show different event types that occurred at each location. The dataset also explores the record counts of various events and severity types. The scatter plot depicts the relationship between the \(fault\_severity\) id and the location of the system in the cluster network. The fault of the system and its severity types (0, 1, 2) are observed at a particular location as shown in Fig. 3.

Data preprocessing

To develop a trustworthy classification system with better performance accuracy, one should comprehend the dataset to extract the significant features. Data preprocessing is a critical step in every deep learning and machine-learning approach. The collected data from the network cluster logs may contain duplicate and superfluous values. The data preprocessing step filters the data by removing the noisy content that affects the system‘s performance. Data preprocessing has a significant role in analyzing the dataset and generating accurate results. The Google Dataprep48 is an intelligent, fully managed dynamic data service to explore, preprocess, visualize, clean, and prepare data for analysis on the Google Cloud Platform. It facilitates creating recipes of transformations on the sample dataset to apply different transformations on the entire dataset. The five critical aspects of Dataprep are data preparation, collection, analytics, management, and storage. The major advantages of using Dataprep are cleaning, combining, and computing multiple huge datasets. Motivated by Dataprep features, the Telstra dataset is normalized before preprocessing steps viz., deduplication, early join, and statistical evaluation, etc. Further, the data is preprocessed in Google Dataprep to check the missing values and detection of any outliers. Additionally, the five different files from the Telstra dataset are joined together based on the key field id into a single dataset. Several features are converted into non-ordinal categorical features and then encoded using label encoding. Now, the final obtained dataset is completely numerical. The data is preprocessed to fit our classification model so that the model can achieve better performance in network failure.

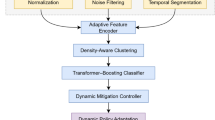

Proposed architecture in virtual machine interpreters

This section introduces the proposed model for Virtual Machine fault classification. This model uses the TabNet architecture based on deep learning, and works on tabular data. This model consists of three modules as feature selection, attention transformer, and feature transformer. The system design of the proposed model is described below.

System design

The TabNet architecture includes a multi-step sequential structure and instance-wise feature selection. For decision-making the TabNet utilizes the decision blocks stationed at different learning steps to focus on processing the input features of the dataset. Internally, the TabNet architecture is a tree-like function that finds the proportion of each feature with the help of a coefficient mask and outperforms the decision trees. The approach followed by the model is as follows:

-

(i)

Use sparse instance-wise feature selection based on learning from the training dataset.

-

(ii)

Build a sequential architecture involving multiple steps to identify the decision step that contributes the most to the final selection of the best features.

-

(iii)

Performing non-linear processing and selecting the best features that can help improve generalization and robustness across diverse datasets.

The feature selection is designed to be instance-wise, which helps the proposed model determine the feature(s) that are concentrated separately for the inputs. Selecting the explicit set of features helps us to determine the sparse features, which results in more efficient learning. The parameters used in each decision stage are used to select the best feature(s). In this design process, the features are extracted and consolidated into a single file for modeling. The working model is discussed below.

The proposed model uses sparse feature selection to select only the relevant and non-redundant feature subset from all the given features, such as location and resource type, as shown in Fig. 4. This model utilizes various decision blocks to check the best subset of input features. The model dynamically selects characteristics based on feedback from previous processes, ensuring adaptive learning. Its decision blocks analyze features by considering location, resource availability, and defect patterns, allowing for precise decision-making. These blocks leverage hierarchical processing to refine feature importance at each stage. This structured approach enhances the model’s ability to generalize and improve accuracy across various scenarios. In this scenario, features (location-related, resources, and fault-related) are processed to predict the severity level (0, 1, 2) of the input features in the Telstra cluster network. The proposed architecture consists of an attention transformer, a feature transformer, and feature masking for each decision step. The architecture employed for the proposed model consists of four steps of evaluation as shown in Fig. 5.

- step 1::

-

The Attention Transformer Block operates by applying a single-layer mapping that processes the values obtained from earlier steps to aggregate and refine the extracted features. It consists of four components: fully connected, Ghost Normalization, multiplication function, and SparseMax layer, as shown in Figure 6. Batch Normalization has been performed, and a SparseMax layer is used to select the best features obtained in each step.

- step 2::

-

The Feature Transformer Block consists of a four-layered network, as illustrated in Fig. 7. This architecture is structured into four levels of blocks, where: Two layers are shared across all decision stages, ensuring consistency and helping the model learn common patterns applicable to multiple tasks. The remaining two layers operate independently, meaning they are unaffected by the judgments made by other decision blocks. These independent layers enable more specialized learning, adapting to specific aspects of the data without interference from other components. This design balances shared feature learning (for generalization) and task-specific adaptation (for fine-tuned decision-making), making the transformer block more flexible and effective in complex scenarios. The architecture comprises four layers of blocks, with two layers shared across all decision steps to ensure consistency in feature extraction. The remaining two layers operate independently, allowing flexibility in decision-making without being influenced by other blocks. This design strikes a balance between global learning with task-specific adaptations, improving overall model efficiency. By combining shared and independent layers, the system achieves both generalization and specialization in processing. Each layer in the block consists of a fully connected layer that detects the global aspects of the features that were detected in the lower layer of the network. A Batch Normalization layer normalizes the input layer for better performance. The mini-batch size during normalization is not defined; therefore, we have used Ghost Batch Normalization (Ghost BN).

- step 3::

-

Feature Masking is employed at each decision step, which can provide insight about the model functionality. Also, provides information regarding the model’s working, which can be used to obtain the global importance of the selected features.

- step 4::

-

: The Split block will split the processed data into two outputs, one of which will be used by the attention transformer in the next step whereas the second output shall be used for the overall results. Furthermore, the ReLU function is used to deal with the non-linearity of the features.

Algorithm

The algorithm for the proposed model is described below.

-

(1)

Feature Selection: For the soft selection of the salient features, a sparse matrix \(M[i] \in \mathbb {R}^{\alpha \times \beta }\) is deliberately chosen, which in turn guarantees that the irrelevant features are masked in each decision step. This enhances the model in the context of parameters and ensures that the learning capacity is retained at each decision step. An attentive transformer is used to obtain the masks from the processed features of the step a[i]:

$$\begin{aligned} M[i+1]=\text {sparsemax}\left( \prod _{j=1}^i(\lambda -M[j]).t_{i+1}(a[i])\right) \end{aligned}$$(2)with the satisfiability of normalization property M[i]:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathop {{\sum }}\limits _{j=1}^\beta M_{b,j}[i]=1 \end{aligned}$$(3)where \(t_i\) is the trainable function. The factor \(\prod _{j=1}^i(\lambda -M[j])\) accounts for the frequency of the usage of a particular feature, termed as scale term P[i], where \(\lambda\) is called a relaxation parameter. Setting \(\lambda =1\) in this factor ensures that a feature is limited to use at a single decision step, and \(\lambda \>1\) triggers the scope of its usage more than once. Hence, at multiple decision steps, a large \(\lambda\) characterizes the model as flexible in the usage of a feature. The initial value of P[i] i.e. P[0] is taken as a constant sequence having unity at each position. The selected features are first passed through a fully connected layer, where they transform to capture complex relationships. A ReLU activation function is then applied to introduce non-linearity, enhancing the model’s ability to learn intricate patterns.

-

(2)

Input Feature: The selected features f belong to batch size \(\alpha\) and its dimension \(\beta\) as follows.

$$\begin{aligned} f\in \mathbb {R}^{\alpha \times \beta } \end{aligned}$$(4) -

(3)

Feature Transformer: It is a four layered network architecture. The first two layers of blocks are shared by all decision blocks, but the latter two layers of blocks are independent of the decisions made by the other decision blocks.

-

(4)

Feature Processing: The output m[i] and n[i] are obtained from the previous step after applying the split function. The n[i] is further used to the prediction results, and m[i] is fed into the following Attention Transformer.

$$\begin{aligned} [n[i],m[i] ]=f_i (M[i].f) \end{aligned}$$(5)where \(n[i]\in \mathbb {R}^{\alpha \times N_n}\) and \(m[i]\in \mathbb {R}^{\alpha \times N_m}\).

-

(5)

Attention Transformer: It aggregates the features using the values collected in the previous phases. M[i].

-

(6)

Final Output: At each stage, the final output fout is summarized by adding all the values received in the preceding phases, and the decision output n[i] is passed using ReLU function.

$$\begin{aligned} f_{out}=\mathop {{\sum }}\limits _{i=1}^{N_{steps}}ReLu(n[i]) \end{aligned}$$(6)

Experimental setup

The classification problem of identifying the severity of the Virtual Machine faults in the Telstra cluster network is executed through experimental analysis. The tabular data used in this experiment is available on Kaggle. Table 2 shows the distribution of the number of fault instances, severity, and severity type in the dataset description. Furthermore, the dataset is divided into two parts: 70% of the sample data is utilized for training, and the remaining 30% is used for validation. The experiments were carried out in Google Colab49 over on this dataset.

The datasets for testing and training are created separately for experimentation. The batch size is set to 1600, which shows that the samples are used for one training step. However, GBN virtual batch size is set as 256, and the number of training epochs and patience (early stopping) is configured to 75 in the validation phase. First, in the preprocessing, the dataset is normalized and statistically evaluated to check the missing values and outliers. Secondly, label encoding is used to convert the categorical data into numerical data for modelling, as shown in Table 3. Python 3.4 with the PyTorch50 environment was used to model the proposed architecture. The model training process can be subdivided into three phases: training, testing, and model performance. At the beginning of the training process, we used different machine learning classification algorithms and trained them to compare their performance with our proposed deep learning model. For the evaluation and comparison of models’ performances, we used different statistical evaluation metrics, namely accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. To model the various machine learning classification algorithms for statistical evaluation, Python 3.4 with Scikit-learn51 was utilized.

The four steps are employed to show the rubric of the proposed architecture. Each step has two independent GLU levels and two shared GLU layers. Our model performs well with the parameter settings and the training process.

Our research work is compared with eight machine learning Algorithms, namely AdaBoost17, K-Neighbors19, Support Vector (SV)52, Random Forest(RF)22, Decision Tree43, Gaussian Naive Bayes (GaussianNB)53, Logistic Regression54, Gradient Boosting24.

Result and discussion

The proposed model’s performance is tested with four metrics: average accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

Table 4 compares the performance of the proposed model with the existing classifiers. The results indicate significant variation in model effectiveness, with the Proposed Model outperforming all traditional classifiers.

Among traditional models, RandomForestClassifier and DecisionTreeClassifier achieve the highest performance, each attaining an accuracy of 0.969. However, while both demonstrate strong F1-scores (0.956 and 0.955, respectively), they fall short compared to the Proposed Model, which yields superior results across all metrics: accuracy (0.983), precision (0.983), recall (0.975), and F1-score (0.979). This highlights not only the model’s robustness but also its balanced predictive capabilities.

In contrast, models such as SVC, LogisticRegression, and GaussianNB perform relatively poorly. The SVC, for instance, shows a particularly low recall (0.216), indicating significant false negatives. LogisticRegression and GaussianNB also struggle, with F1-scores of 0.335 and 0.430, respectively, making them less suitable for the problem context.

The KNeighborsClassifier and GradientBoostingClassifier perform moderately well, with F1-scores of 0.642 and 0.612, respectively. While these models offer a reasonable trade-off between precision and recall, they still lag behind ensemble-based methods like Random Forest and the proposed model.

The AdaBoostClassifier achieves moderate results with an F1-score of 0.515, reflecting its sensitivity to noisy data and outliers. This performance gap further emphasizes the need for robust feature selection and model tuning, as implemented in the Proposed Model. The proposed model has an accuracy score of 98.3%. Table 4 shows the efficacy of the suggested model in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score. The comparison study is also visually depicted in Fig. 8a–d to illustrate the power of the proposed model. The suggested model outperforms not only in terms of accuracy, as described above, but also in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score, with 98.3%, 97.5%, and 97.9%, respectively. The training/validation loss and accuracy curves of the proposed model indicate how the model improved over time, with the errorloss monotonically falling, as shown in Fig. 9, and the accuracy approaching 98% as depicted in Fig. 10.

Conclusion

Our research work utilizes the enhanced version of TabNet Architecture for feature selection on various tabular data using deep learning. Such neural nets help with fault classification with improved accuracy and precision for virtual machine interpreters. The effectiveness of the proposed model is tested on the tabular dataset of the Telstra cluster network. In the experimentation, average accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores have been observed with 98.3%, 98.3%, 97.4%, and 97.8%, respectively. Such performance metrics exhibit the efficiency of the proposed model on simulation with eight different machine learning classifiers like AdaBoost Classifier, K-Neighbors Classifier, Support Vector Classifier, Random Forest Classifier, Decision Tree Classifier, Gaussian Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, and Gradient Boosting Classifier. The implementation of the proposed model will be extended in the future with real-time series data prediction to investigate the live data streaming on tabular data.

Data availability

The data used in this study is collected from Kaggle, which is provided by the Telstra cluster network and available at https://www.kaggle.com/c/telstra-recruiting-network

References

Nicolae, B. & Cappello, F. BlobCR: virtual disk based checkpoint-restart for HPC applications on IaaS clouds. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpdc.2013.01.013 (2013).

Araujo Neto, J. P., Pianto, D. M. & Ralha, C. G. MULTS: a multi-cloud fault-tolerant architecture to manage transient servers in cloud computing. J. Syst. Archit. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sysarc.2019.101651 (2019).

Manasrah, A. M., Aldomi, A. & Gupta, B. B. An optimized service broker routing policy based on differential evolution algorithm in fog/cloud environment. Cluster Comput. 22, 1639–1653 (2019).

Beaumont, O., Eyraud-Dubois, L. & Lorenzo-Del-Castillo, J. A. Analyzing real cluster data for formulating allocation algorithms in cloud platforms. Parallel Comput. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parco.2015.07.001 (2016).

Xu, M. et al. Multiagent federated reinforcement learning for secure incentive mechanism in intelligent cyber-physical systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 22095–22108 (2021).

Egwutuoha, I. P., Levy, D., Selic, B. & Chen, S. A survey of fault tolerance mechanisms and checkpoint/restart implementations for high performance computing systems. J. Supercomput. 65, 1302–1326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-013-0884-0 (2013).

Walters, J. P. & Chaudhary, V. Replication-based fault tolerance for MPI applications. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2008.172 (2009).

Roman, E. A survey of checkpoint/restart implementations. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Tech 1–9 (2002).

Yamin, A. C. et al. A framework for exploiting adaptation in high heterogeneous distributed processing. In Proceedings - Symposium on Computer Architecture and High Performance Computing. https://doi.org/10.1109/CAHPC.2002.1180768 (2002).

Egwutuoha, I. P., Chen, S., Levy, D., Selic, B. & Calvo, R. Cost-oriented proactive fault tolerance approach to high performance computing (HPC) in the cloud. Int. J. Parallel Emerg. Distrib. Syst. 29, 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445760.2013.803686 (2014).

Rawat, A., Sushil, R., Agarwal, A. & Sikander, A. A new approach for VM failure prediction using stochastic model in cloud. IETE J. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2018.1537814 (2018).

Aznar, F., Pujol, M. & Rizo, R. Obtaining fault tolerance avoidance behavior using deep reinforcement learning. Neurocomputing https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2018.11.090 (2019).

Aslan, E., Özüpak, Y., Alpsalaz, F. & Elbarbary, Z. M. S. A hybrid machine learning approach for predicting power transformer failures using internet of things-based monitoring and explainable artificial intelligence. IEEE Access 13, 113618–113633. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3583773 (2025).

Ajmal, M. S. et al. Hybrid ant genetic algorithm for efficient task scheduling in cloud data centers. Comput. Electr. Eng. 95, 107419 (2021).

Malyuga, K., Perl, O., Slapoguzov, A. & Perl, I. Fault tolerant central saga orchestrator in RESTful architecture. In Conference of Open Innovation Association, FRUCT. https://doi.org/10.23919/FRUCT48808.2020.9087389 (2020).

Zaidi, S. M. H. et al. Intelligent process automation using artificial intelligence to create human assistant. Int. J. Softw. Sci. Comput. Intell. (IJSSCI) 17, 1–19 (2025).

Bartlett, P. L. & Traskin, M. AdaBoost is consistent. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7503.003.0018 (2007).

Guo, H. & Deng, S. Condition identification of calcining kiln based on fusion machine learning and semantic web. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 21, 1–36 (2025).

Cunningham, P. & Delany, S. J. K -Nearest neighbour classifiers. Multiple Classifier Syst. (2007).

Fulp, E., Fink, G. & Haack, J. Predicting computer system failures using support vector machines. In Proceedings of the First USENIX conference on Analysis of system logs (2008).

Safavian, S. R. & Landgrebe, D. A survey of decision tree classifier methodology. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. https://doi.org/10.1109/21.97458 (1991).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Ali, S. S., Ganapathi, I. I., Mahyo, S. & Prakash, S. Polynomial Vault: a secure and robust fingerprint based authentication. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETC.2019.2915288 (2019).

Liu, X. & Yu, T. Gradient feature selection for online boosting. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2007.4408912 (2007).

Ye, N. & Ye, N. Naïve bayes classifier. In Data Mining. https://doi.org/10.1201/b15288-3 (2020).

Özüpak, Y., Alpsalaz, F. & Aslan, E. Air quality forecasting using machine learning: comparative analysis and ensemble strategies for enhanced prediction. Water Air Soil Pollut. 236, 464 (2025).

Chigurupati, A., Thibaux, R. & Lassar, N. Predicting hardware failure using machine learning. In 2016 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS) 1–6 (IEEE, 2016).

Jain, D. K., Eyre, Y.G.-M., Kumar, A., Gupta, B. B. & Kotecha, K. Knowledge-based data processing for multilingual natural language analysis. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resource Lang. Inf. Process. 23, 1–16 (2024).

Muchandigona, A. K. Financial perspectives of business services migration to the cloud in public sector. Int. J. Cloud Appl. Comput. (IJCAC) 15, 1–28 (2025).

Yann, L. C. et al. Deep learning. Nature (2015).

Arel, I., Rose, D. & Karnowski, T. Deep machine learning-a new frontier in artificial intelligence research. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCI.2010.938364 (2010).

Goyal, S. et al. Synergistic application of neuro-fuzzy mechanisms in advanced neural networks for real-time stream data flux mitigation. Soft Comput. 28, 12425–12437 (2024).

Raihan, M. & Kurniawati, H. Transformation of external auditors in audit practices through the use of cloud technology. Int. J. Cloud Appl. Comput. (IJCAC) 15, 1–30 (2025).

Netti, A. et al. A machine learning approach to online fault classification in HPC systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2019.11.029 (2020).

Arik, S.Ö. & Pfister, T. TabNet: attentive interpretable tabular learning. ArXiv abs/1908.0 (2019).

Grabczewski, K. & Jankowski, N. Feature selection with decision tree criterion. In Proceedings - HIS 2005: Fifth International Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICHIS.2005.43 (2005).

Ho, T. K. The random subspace method for constructing decision forests. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1109/34.709601 (1998).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining.https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (2016).

Ke, G. et al. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Humbird, K. D., Peterson, J. L. & Mcclarren, R. G. Deep neural network initialization with decision trees. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2869694 (2019).

Kontschieder, P., Fiterau, M., Criminisi, A. & Bulo, S. R. Deep neural decision forests. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2015.172 (2015).

Kontschieder, P., Fiterau, M., Criminisi, A. & Bulò, S.R. Deep neural decision forests. In IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2016).

Trees, Decision. In SpringerReference. https://doi.org/10.1007/springerreference_63657 (2011).

Hoang, D. T. & Kang, H. J. A survey on Deep Learning based bearing fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2018.06.078 (2019).

Bughin, J., Seong, J., Manyika, J., Chui, M. & Joshi, R. Notes from the AI frontier: Modeling the global economic impact of AI Tech. Rep. (2018).

Nishida, K., Sadamitsu, K., Higashinaka, R. & Matsuo, Y. Understanding the semantic structures of tables with a hybrid deep neural network architecture. In 31st AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2017 (2017).

Telstra. Telstra network disruptions, version 1 (2015, accessed 20 Aug 2020).

Bisong, E. & Bisong, E. Google cloud dataprep. In Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-4470-8_39 (2019).

Google Colab. Welcome to Colaboratory - Colaboratory (2020).

Paszke, A. et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2019).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. (2011) .

Chang, C. C. & Lin, C. J. LIBSVM: a Library for support vector machines. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1145/1961189.1961199 (2011).

Ye, N. Naive bayes classifier. In Data Mining https://doi.org/10.1201/b15288-3 (2020).

Peng, C. Y. J., Lee, K. L. & Ingersoll, G. M. An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. J. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670209598786 (2002).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, literature survey, data collection, and software were performed by Ajay Rawat, Anupama Mishra, Hind Alsharif, Reem M. Alharthi, and Brij B. Gupta. All authors performed the data analysis and validation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ajay Rawat and all authors reviewed and provided feedback on all the versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The used dataset is publicly available on Kaggle and also cited in the text.

Human participants and/or animals

This research work has not involved any kind of experiments on Humans and/or Animals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rawat, A., Mishra, A., Alsharif, H. et al. Fault classification in the architecture of virtual machine using deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 34469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17109-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17109-8