Abstract

The accuracy of cross-time-scale runoff prediction is affected by data characteristics, and accuracy improvement is challenging. This study examined 18,250 global hydrological stations, identified the multi-scale effect of runoff time series (MSER), and proposed an MSER-based improved prediction method (MSEIP). It introduced models, such as multiple linear regression (MLR) and Gaussian process regression (GPR), and evaluation metrics, including optimization proportion (OP) and optimization efficiency (OE), for comparative analysis. The results showed that MSER is applicable to over 73% of hydrological stations, and its applicability increases with larger flow rates. The improvement effect of MSEIP is negatively correlated with time scales (weekly to yearly scale, OPMAE: 0.99–0.60) and positively correlated with flow rates (from less than 100 to more than 2000 m3/s, OPQR: 0.6–0.85). MLR is suitable for identifying MSER at small scales (OPMAE of 1 at the weekly scale), while GPR performs better at large scales (seasonally and yearly scales, GPR’s OPQR is 0.67 and 0.58, respectively, higher than MLR’s 0.29 and 0.21). MSER explains differences in runoff prediction accuracy across time scales from data characteristics, and MSEIP provides technical support and a reference for improving cross-scale prediction accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global climate change and intense human activities have exacerbated the uncertainty of hydrological systems, highlighting the significance of runoff forecasting in basin planning, flood control, drought relief, and ecological security1,2. Runoff forecasting involves many practical challenges, and within the context of multi-scale research, two specific issues merit attention. First, the causal mechanisms underlying prediction accuracy across different time scales remain unclear. Second, the application of multi-scale data to enhance prediction accuracy is still inadequate.

Hydrological forecasting methods are roughly divided into process-driven and data-driven models3. Process-driven models simulate the physical process of rainfall-runoff conversion through conceptual or distributed frameworks with physical interpretability4,5. However, process-driven models are highly dependent on detailed basin data, such as topography and soil properties. When there are data gaps or errors, their ability to characterize key processes is weakened, leading to prediction deviations6,7,8. Data-driven models use machine learning algorithms to mine hidden patterns and spatiotemporal correlation characteristics of runoff series and show excellent performance in flexibility and adaptability9,10,11,12. Nevertheless, data-driven models lack physical interpretability, face difficulties in generalizing to extreme events, and are at a risk of overfitting13,14,15,16. Although innovative methods such as gated recurrent unit (GRU)17,18, time convolution network (TCN)19,20, and deep autoregressive model (DeepAR)21,22 have improved the prediction performance of runoff time series at single time scales, these models have not addressed cross-scale challenges.

Most current studies focus on single time scales, and cross-scale prediction methods are still in the exploratory stage23. Runoff prediction accuracy decreases continuously with an increase in time scales, among which predictions at small time scales, such as daily and weekly scales often perform well24,25. This highlights the untapped potential of integrating multi-scale data to improve predictions at large time scales.

This study aims to address the deficiencies in the cross-scale prediction of multi-time-scale runoff time series. Taking 18,250 hydrological stations worldwide as the research object, this study explored the characteristics of multi-scale effects in runoff time series and proposed a solution to improve the accuracy of multi-time-scale prediction. We: (1) Use multiple correlation coefficients to quantify the autoregressive characteristics of 18,250 global hydrological stations at different time scales and analyzed the patterns of MSER characteristics; (2) Verified the feasibility of the MSEIP method through the analysis of 8 stations, and introduced optimization proportion (OP) and optimization efficiency (OE) metrics to analyze model performance; (3) Tested the universality of the MSEIP method in global stations; (4) For stations where the MSEIP method performs poorly in prediction, heterogeneous mechanism models were supplemented to identify the reasons for inapplicability. The research results reveal the decay law of MSER characteristics and establish the MSEIP framework, which realizes the transfer of prediction from small to large time scales and improves the prediction accuracy at large scales. This study aims to improve forecast accuracy, with more precise predictions expected to support practical efforts, such as water resource management, while offering theoretical and methodological insights for multi-scale hydrological forecasting.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. “Methodology” introduces the definition and discrimination method for the MSER and MSEIP methods. “Case study” presents the research area and experimental results. “Discussion” provides discussion. “Conclusion” summarizes the conclusion.

Methodology

Definition of multi-scale effects in runoff time series

From the studies of Rahmani, it is known that long-term hydrological time series usually exhibit core features, such as long-term trends, periodic fluctuations, random noise, autocorrelation, and chaotic characteristics, whereas short-term series may lack obvious trends or periodic fluctuations due to limited time spans26,27. These features form a hierarchical structure of information: long-term trends reflect the macro evolutionary trajectory of the basin; periodic fluctuations encode cyclical drivers such as seasonal hydrology; autocorrelation and chaotic characteristics embody the subtle dependencies between consecutive states; and this hierarchical difference is crucial for distinguishing signal patterns across different scales28,29,30.

Watershed regulation and water conservancy project operations often involve cross-scale decision-making, thus requiring multi-time-scale runoff prediction. However, resampling runoff time series to larger scales smooths out high-frequency variations, such as short-term rainfall-runoff responses or diurnal flow fluctuations, thereby weakening the original signal. This smoothing is not merely a mathematical operation but a reflection of the transition of physical processes: runoff at small scales is dominated by immediate local interactions (e.g., raindrop impact, overland flow convergence), with each time step retaining a strong “memory” of previous states, thus resulting in pronounced autoregressive characteristics. In contrast, larger scales integrate these local processes into basin-wide cumulative effects (e.g., year-scale water balance and groundwater storage changes), where short-term “memories” are diluted by the aggregation process, leading to weakened autoregressive characteristics. This scale-dependent shift in the dominance of processes is what we term the multi-scale effect of the runoff time series (MSER).

The identification of MSER characteristics in the runoff time series involves the use of multiple correlation coefficients to quantify the strength of autoregressive characteristics across different scales. Specifically, if the multiple correlation coefficient of the runoff time series decreases with increasing scale, it indicates that autoregressive characteristics decline at larger scales, thereby confirming the presence of MSER characteristics. Physically, this pattern embodies the transition from "event-driven processes" at small scales (e.g., storm runoff) to "equilibrium-dominated processes" at large scales (e.g., year-scale runoff). This transition means that the information content supporting predictability undergoes fundamental changes across scales: small scales rely on fine-grained temporal correlations, whereas large scales depend on the comprehensive properties of the basin, which is consistent with the logic of parsing and prioritizing information hierarchies in complex system analysis.

In this study, the multiple correlation coefficient serves two roles: identifying MSER characteristics and screening input variables to determine the amount of historical data used for runoff prediction. It quantifies the overall correlation between the linear combination of the dependent and independent variables through a multiple linear regression model. The specific method involves calculating the multiple correlation coefficient using formula (1) and (2).

where \(\alpha_{0} ,\alpha_{1} ,\alpha_{2} , \ldots ,\alpha_{k}\) are regression coefficients; \(\hat{y}\) is the predicted value of linear regression; \(y\) is the actual observed runoff; \(\overline{y}\) is the actual observed mean runoff.

Improved prediction method based on MSER

Based on the MSER characteristic of the runoff time series, this study proposes an improved prediction method to address the excessive decay of the forecasting accuracy of runoff time series across different temporal scales.

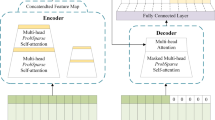

The specific implementation steps of the MSEIP method for different temporal scales are as follows. When weekly scale prediction is required, multi-step forecasting is performed using daily scale runoff time series data, and the results of multi-step forecasting are averaged as the weekly scale prediction result, denoted as MSEIP-w. When monthly scale prediction is required, multi-step forecasting is performed using weekly scale runoff time series data, and the results are averaged as the monthly scale prediction result, denoted as MSEIP-m. Similarly, seasonally scale prediction uses monthly scale multi-step forecasting, denoted as MSEIP-y. In contrast, the commonly used conventional prediction method at present, namely, direct prediction at large temporal scales, is abbreviated as DPL for ease of description. In the DPL, weekly scale prediction is denoted as DPL-w, monthly scale prediction as DPL-m, seasonally scale prediction as DPL-s, and yearly scale prediction as DPL-y. The technical roadmap of MSEIP is shown in Fig. 1, and the technical roadmap for multi-step forecasting is shown in Fig. 2.

Data driven runoff forecasting models

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MSEIP framework, we selected seven representative models covering linear statistical, nonlinear extended, and deep learning methods for short-term runoff prediction across multiple time scales. These models were chosen to encompass various methodological paradigms, ranging from simple linear relationships to complex nonlinear mappings, static statistical fitting to dynamic sequence learning, and deterministic prediction to probabilistic inference31,32,33,34. This diversity ensures that we can rigorously test the adaptability of the MSEIP framework under different modeling philosophies and identify its added value compared with traditional methods. The selected models were as follows:

Multiple linear regression (MLR)35: A basic linear statistical model that assumes the dependent variable \(y\) is the sum of the linear combination of multiple independent variables \(x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots x_{n}\) and the error term, and its mathematical expression is shown in formula (3).

where \(b_{0} ,b_{1} , \ldots b_{n}\) are regression coefficients and \(\varepsilon\) is random errors.

Polynomial regression (PR)36: An extension of linear regression that extends linear regression to a nonlinear model by introducing higher-order terms of independent variables (such as square and cubic terms). Its general form is shown in formula (4).

where \(b_{0} ,b_{1} ,b_{2} , \ldots b_{m}\) are polynomial coefficients.

Deep neural network (DNN)37,38: A multi-layer nonlinear model that constructs multi-layer nonlinear mapping by stacking multiple hidden layers (such as a full connection layer). Its structure includes an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. The network adjusts the weight \(W\) and bias \(b\) of each layer using a back-propagation algorithm to minimize the prediction error31. The output \(y_{l}\) of layer \(l\) can be expressed as formula (5).

where \(\sigma\) is the activation function.

Gated recurrent unit (GRU): A simplified version of the long-term and short-term memory network (LSTM), which captures the long-term dependence of sequence data by introducing “update gate” and “reset gate”. The core formula is formula (6).

where \(f\) is element by element multiplication.

Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN): A model optimized for a time series that combines causal convolution (ensuring time order) and extended convolution (expanding receptive field), which is suitable for time series prediction. The output \(y(t)\) is calculated by the weighted sum of the historical input \(x(t - k)\)32. The formula is shown in formula (7).

where \(w_{k}\) is the weight of convolution kernel; \(K\) is the convolution kernel size.

Deep autoregressive (DeepAR) model: A probability prediction model that combines autoregressive logic with a recurrent neural network (RNN) to learn the conditional probability distribution of a time series. The main formula is formula (8).

where \(y_{t}\) is the prediction data at time t; \(y_{1:t - 1}\) is historical observation data; External covariates of \(x_{1:t - 1}\); \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are the mean and standard deviation functions determined by the neural network parameter \(\theta\); \({\mathcal{N}}\) is the Gaussian distribution.

Gaussian process regression (GPR)34,39: A Bayesian nonparametric model that assumes data are generated by the Gaussian process. The covariance function is used to describe the correlation of the data points to fit the training data and then realize the prediction. The formula is (9).

where \(y{\prime}\) is the predicted value; \({\text{K}}\) is the historical observation data of covariance matrix of \(n \times n\); \({\text{k}}_{*}^{{}}\) is an n-dimensional vector; \(\sigma_{n}^{2}\) is the variance of observation noise; \({\text{I}}\) is the identity matrix of \(n \times n\); \(y\) is the observation vector corresponding to the training data.

Simple data preprocessing

To preserve the authenticity of the characteristics of runoff time series across different time scales, this study only conducted necessary minimal processing to avoid excessive operations from obscuring intrinsic multi-scale characteristics. The specific steps were as follows: (1) For stations with continuous missing segments shorter than one day, linear interpolation was used to fill the gaps to maintain local trends; otherwise, the station was excluded; (2) The sliding window interquartile range method was adopted to identify outliers, which were then processed using linear interpolation.

In this study, all modeling and data analyses were performed using Python 3.9.

Prediction performance evaluation indicators

To comprehensively evaluate the prediction performance of the model, the following evaluation indices were selected in this study: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), qualified rate (QR), Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (NSE), and maximum error (ME). The mathematical expression for the evaluation index is as follows:

where \(Q_{Ot}\) and \(Q_{St}\) are measured and predicted flow values at time t respectively; \(n\) is the total number of time periods included in the hydrological sample data; \(k\) is the number of samples in which the relative error between the measured flow and the predicted flow is less than 20%; The range of \(MAE\) and \(RMSE\) values is [0, + ∞), the closer to 0 means the smaller the prediction error; \(QR\) value range is [0, 1], the closer to 0 means the lower the reliability of the prediction result and the closer to 1 means the higher the reliability of the prediction result; The range of \(NSE\) value is (− ∞, 1]. The closer to 1, the higher the prediction accuracy. The range of the \(ME\) value is [0, + ∞]. The closer it is to 0, the more accurate the prediction result; the larger the value, the worse the accuracy of the forecast in the most extreme cases.

Due to the large number of sites, in order to facilitate the evaluation of the forecasting effect of MSEIP, optimization proportion (OP) and optimization efficiency (OE) indicators are adopted. The mathematical expressions are as follows:

Among all sites, \(N_{m}\) represents the number of sites where each evaluation metric performs better in MSEIP than in DPL. \(N\) represents the total number of sites involved in the calculation. The optimization proportion (OP) for each evaluation indicator is defined using the following metrics: optimization proportion mean absolute error (OPMAE), optimization proportion root mean square error (OPRMSE), optimization proportion qualified rate (OPQR), optimization proportion Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (OPNSE), and optimization proportion maximum error (OPME). The OP values range from [0,1], and the closer the value is to 1, the more sites MSEIP outperforms DPL among all sites.

where \(I_{m}\) represents the evaluation index of MSEIP, and \(I\) represents the evaluation index of DPL. The optimization efficiency (OE) for each evaluation indicator was defined using the following metrics: optimization efficiency mean absolute error (OEMAE), optimization efficiency root mean square error (OERMSE), optimization efficiency qualified rate (OEQR), optimization efficiency Nash Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (OENSE), and optimization efficiency maximum error (OEME). The value ranges for OEMAE, OERMSE, OEME, OEQR, and OENSE are all [− 100, + ∞). The closer OEMAE, OERMSE and OEME are to − 100, the more significant the improvement in the predictive effect of MSEIP compared to DPL. For OEQR and OENSE, the opposite is true; the larger the value, the better.

Case study

Study area and data

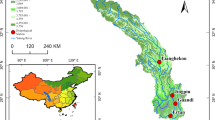

The streamflow observation data for over 20,000 rivers worldwide (1979–2013) used in this study are derived from the SWOT Global Reach-level A priori Discharge Estimates (GRADES) data archive developed by Lin et al.40. For detailed descriptions of this global discharge database, please refer to the following paper: https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025287. This study selected 18,250 hydrological stations distributed across different climate zones and geomorphic units to construct a global multi-scale runoff dataset. Site selection adheres to the principles of spatial representativeness and data continuity, covers tropical to cold climate regions, and includes natural watersheds as well as systems affected by human activities. Additionally, eight typical stations were chosen as cases, and seven hydrological prediction models (MLR, PR, DNN, GRU, TCN, DeepAR, and GPR) were used to verify the model dependence of MSER characteristics. The global-scale analysis integrates the time-series data of 18,250 stations, focusing on analyzing the regulatory effects and boundary conditions of different flow magnitudes on the MSER. The study area is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Value range of number of lag order

In this study, when selecting the lag order based on the multiple correlation coefficient method, the optimal lag order is determined by selecting the value that maximizes this coefficient within a preset range to ensure the model fitting effect. The selection range of lag orders for different time scales was determined through verification by pre-experiments, which calculated the multiple correlation coefficients for a large number of lag orders at various scales in some stations, and found that they all first increased rapidly with the lag number, then entered a stable stage, and there were no significant fluctuations or increases in the multiple correlation coefficients when the lag order continued to increase. Verification shows that when using lag numbers within this range for prediction, the model fitting is robust; exceeding the range cannot significantly improve performance but instead increases the computational burden, whereas an overly narrow range will miss key lag orders, leading to a decrease in accuracy. Therefore, Table 1 was selected as the selection range for lag orders.

Parameter setting of forecasting model

The PR model was constructed in the form of a quadratic polynomial, and the GPR model used a radial basis kernel function. For the DNN, TCN, GRU, and DeepAR models, the number of hidden layers listed in Table 2 was determined through pre-experiments, and the number of neurons in each hidden layer was determined using the grid search optimization method. Specifically, we first conducted pre-experiments to determine the number of hidden layers, then adopted the grid search hyperparameter optimization method to perform optimization within the parameter range of each model, evaluated the performance of each set of parameters based on the prediction error of the validation set, and finally selected the combination with the smallest error as the optimal parameter of the model.

Analysis of multi-scale effects in runoff time series at global hydrological stations

In this study, a case study involving 18,250 stations worldwide was conducted. The multiple correlation coefficient was calculated for the daily, weekly, monthly, seasonal, and yearly runoff data of these stations to investigate the autoregressive characteristics of the hydrological time series across different time scales. Specifically, Fig. 4 provides an overview of how the multiple correlation coefficient changes with the increase in time scale for the 18,250 global stations, where black dots represent stations consistent with the decrease in the multiple correlation coefficient with time scale and red dots represent inconsistent cases. Figures 5 and 6 depict the proportion and number of stations across different flow ranges among all stations, in which the multiple correlation coefficient decreases as the time scale decreases.

As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, for stations in the large flow range (over 2000 m3/s), the proportion of stations where the multiple correlation coefficient decreased with increasing time scale was generally higher than 0.91:0.918 for 2000–5000 m3/s and 1 for over 10,000 m3/s, indicating the high stability of the MSER characteristic in large flow ranges. In the medium flow range (100–2000 m3/s), the proportion increased from 0.702 (100–500 m3/s) to 0.739 (500–1000 m3/s), and finally to 0.834 (1000–2000 m3/s), showing that the MSER characteristic applicability strengthens with increasing flow. For the low-flow range (less than 100 m3/s), the proportion drops significantly; the values are 0.467 for 0–20 m3/s and 0.550 for 50–100 m3/s, indicating that the MSER characteristic is less evident in the low-flow range.

It can be seen that in low-flow systems, the characteristics of noise dominance, significant nonlinear effects, and constrained data quality lead to a weaker manifestation of the attenuation law of MSER. According to a study by Rahmani and Fattahi on the 13-year daily hydrological time series of the Parishan Lake sub-basin in the Helle Basin, Iran, after wavelet transform denoising, the prediction errors of the models were significantly reduced, and the correlation and autocorrelation of the series were simultaneously enhanced27. Therefore, in hydrological modeling, random interference can be offset through noise suppression algorithms, and complex interactions can be characterized by nonlinear correction terms to avoid systematic errors in runoff prediction.

Analysis of results of the MSEIP method at 8 randomly selected hydrological stations

To validate the application of the MSER conclusion in runoff prediction, this study randomly selected 8 stations from 18,250 global stations, used 7 prediction models, and applied MSEIP. The results of the OPMAE index are shown in Fig. 7, and those of the OPQR index are shown in Fig. 8. The remaining indices, OPRMSE, OPNSE, and OPME, are shown in Supplementary Figs. S1–S3. The average values of the specific evaluation indicators in the MLR and GPR models for the 8 stations are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

As shown in Figs. 7 and 8 and Supplementary Figs. S1–S3 at MSEIP-w, all indicators of MLR reach 1.0, whereas GPR only achieves an OPQR of 1.0, with slightly lower values in other indicators, highlighting MLR’s significant advantage of MLR. At MSEIP-m, MLR maintains all indicators at 1.0, demonstrating clear dominance; the GRU model has an OPME of 0.5 but achieves 1.0 in all other indicators, second only to MLR. The DeepAR model reaches 1.0 in OPMAE and OPNSE models, the DeepAR models show poor performance. These results indicate that MLR has overwhelming advantages for short-to medium-term forecasting. At the MSEIP-s, MLR’s OPMAE and OPRMSE remain at 1.0, although its advantage is relatively reduced compared with short-term forecasting, with other indicators below 1.0. The GPR and PR models exhibited outstanding performance in OPQR, reaching 0.875 and exceeding the MLR 0.75. At MSEIP-y, MLR’s OPMAE and OPRMSE are 0.75 and 0.875, respectively, the best among all models, while other models generally show indicators below 0.75. The significant performance decline across all models corroborates the theoretical characteristics of the MSER. Overall, MLR was preferred as the primary model for the global validation of MSER characteristics, followed by GPR.

At MSEIP-s, MLR’s OPQR of 0.75 is lower than GPR’s 0.875. Analysis of the model error metrics in Supplementary Table S1 shows that for seasonally scale prediction, MLR using the MSEIP-s method yielded an average QR of 0.569 across 8 stations, compared to GPR’s 0.428, a 32.8% improvement. In contrast, MLR using the DPL-s method had an average QR of 0.468, versus GPR’s 0.352, a 33.0% improvement. Both models demonstrated better performance with the MSEIP method than with the DPL method, further validating the MSER characteristics. Collectively, MLR significantly outperformed GPR at these 8 stations, confirming its role as the model of choice for global validation.

Analysis of results of the MSEIP method at hydrological stations globally

In this study, the MLR model was applied to 13,385 stations conforming to the MSER characteristics to verify the MSEIP method. Through the analysis of the prediction effects, it was found that there are significant differences in the optimization efficiency of the MSEIP method across different flow rate ranges. The results of the OEMAE indicator at the weekly, monthly, seasonal, and yearly scales for 13,385 global hydrological stations are shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12. The remaining result charts for OERMSE, OEME, OEQR, and OENSE across different time scales are presented in Supplementary Figs. S4–S19. The results of the OPMAE and OPQR indicators across multiple time scales and different discharge ranges are shown in Figs. 13 and 14. The remaining OPRMSE, OPME, and OPNSE results are presented in Supplementary Figs. S20–S22.

As shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 and Supplementary Figs. S4–S22. In the large flow range (over 2000 m3/s), the OP of the prediction effect of each time scale was the most significant. For example, the OP of each index of MSEIP-w generally exceeded 0.97, and OPMAE, OPRMSE, and OPNSE reached 1. The OP of MSEIP-m indicators is still greater than 0.75, and OPMAE, OPRMSE, and OPNSE are as high as 0.84. MSEIP-s is similar to MSEIP-m, and the OP of each index exceeds 0.71. The OP of MSEIP-y decreased slightly but still exceeded 0.63. These results indicate a high level of validation consistency for the MSER characteristic in large-flow regimes, and the MSEIP method demonstrates significant improvements over the DPL method in prediction accuracy.

The medium flow range (100–2000 m3/s) was characterized by transition. The MSEIP-w OP is outstanding, with OPMAE, OPRMSE, OPQR, and OPNSE reaching 0.98, and OPME reaching 0.93. With an increase in scale, the OP exhibits a stepped attenuation. The OP of MSEIP-m was similar to that of MSEIP-s, and the worst attenuation of each index was 0.63. The OP of MSEIP-s is the worst and further decreases to 0.55–0.65, but MSEIP still has more than half of the advantages. Specifically, the MSEIP method outperformed the DPL method in terms of error indicators for more than half of the stations.

The OP of the small flow range (less than 100 m3/s) is the lowest, especially on the long-term scale. The OP in MSEIP-w is still outstanding, the OP of each index is more than 0.88 and OPMAE, OPRMSE, and OPNSE are greater than 0.99. MSEIP-m and MSEIP-s decline severely, and the OP of each index is only 0.59–0.70 and 0.51–0.61 respectively. MSEIP-y shows similar trends to MSEIP-s, with slight further decreases in some indices. The OP values were only 0.53–0.59. This indicates that the validity of the MSER characteristic decreases gradually with increasing time scale in small flow regimes.

Notably, all flow magnitude ranges exhibited strong OP values at MSEIP-w, with the OPMAE exceeding 0.99. With an increase in time scale and decrease in flow magnitude, the OP demonstrates a gradual attenuation trend. Stations in the large and medium flow magnitude ranges exhibited the most pronounced OP values at MSEIP-w and MSEIP-m, whereas stations in the small flow magnitude ranges only excel at MSEIP-w, showing mediocre OP performance at other scales. This highlights that the MSER characteristic is more applicable to large and medium flow magnitude ranges, whereas its validity in small flow magnitude ranges is limited to short-term MSEIP-w forecasting.

Analysis of results of prediction models with different mechanisms for the MSEIP method

Among the 13,385 global stations conforming to MSER characteristics, 24 stations with poor prediction results were randomly selected. Predictions were then performed using the GPR model and MSEIP to test whether the linear assumption of MLR fails to capture the complex characteristics of MSER. The OP indicators of the prediction results for the 24 hydrological stations are shown in Fig. 15.

As shown in Fig. 15, at MSEIP-w, MLR’s OPMAE, OPRMSE, and OPNSE values all reached 1.0, with only OPQR slightly lower than GPR. This highlights the MLR’s ability to identify MSER characteristics at the weekly scale of the MSEIP method. At MSEIP-m and MSEIP-s, GPR’s nonlinear fitting capability gradually becomes evident: GPR demonstrates a significant advantage over MLR in the OPQR metric, while MLR underperforms GPR across all indicators. At MSEIP-s, both models exhibited degraded performance, although GPR still outperformed MLR. Notably, MLR recorded values of 0 for OPRMSE and OPME, indicating that its MSEIP method produced worse predictions than the DPL method at these 24 stations. In contrast, GPR achieves values of 0.167 and 0.333 for these metrics, highlighting GPR’s stronger ability to capture the MSER characteristic in long-term runoff prediction.

The performance discrepancy between MLR and GPR was attributed to their model assumptions. MLR’s linear assumption of MLR imposes performance constraints that intensify with increasing temporal scales, rendering it inadequate for characterizing the nonlinear dynamics of runoff. GPR’s advantage lies in the adaptability of its kernel function, which effectively simulates nonlinear features and mitigates MLR’s limitations of MLR at long scales.

Overall, in stations where MLR demonstrated poor adaptability, deploying GPR provided a more robust validation of the applicability of the MSER characteristic.

Discussion

This study focuses on discovering MSER characteristics and validating the effectiveness of the proposed MSEIP. Studies have shown that over 73% of the hydrological stations exhibit significant MSER characteristics. Based on the MSER characteristic, compared with DPL, MSEIP effectively reduces prediction errors in weekly runoff forecasting and performs well at monthly, seasonal, and annual scales, but there are still some limitations.

Chen et al. achieved multi-scale modeling by capturing temporal resolution through patch partitioning and dual attention41, whereas this study focused on quantifying autoregressive characteristics to realize prediction from small to large time scales. This study uses the multiple correlation coefficient to quantify autoregressive characteristics, which is similar to Zhang et al., who applied Pearson’s correlation to analyze lags42, both confirming the practicality of linear indicators. However, runoff exhibits certain chaotic characteristics and nonlinearities. The use of linear relationships to quantify autoregressive characteristics has certain limitations. Future work should consider the impact of characteristics, such as nonlinearity. Owing to limitations in computing resources, only the MLR model was used for global verification, and a few stations were randomly selected to use seven prediction models for verification. Although the existing results can prove the effectiveness of the proposed MSEIP, it is planned to use more comprehensive prediction models for verification globally in the future, such as introducing high-performance cluster computing systems and establishing combined prediction models43,44,45. This study only considered the runoff of the stations as input, without considering the river morphology and climatic characteristics. In the future, it will be necessary to integrate multi-source data, including river geometric and meteorological parameters retrieved from satellite remote sensing, to analyze the environmental dependence of multi-scale effects.

It should be emphasized that the core of runoff forecasting remains reliant on process-driven models. While data-driven methods can efficiently mine temporal patterns, they mostly stay at the level of “phenomenal correlation” and struggle to explain core mechanisms such as runoff generation and concentration and groundwater-surface water interactions. In cases of extreme events or abrupt changes in underlying surfaces, they are prone to deviations owing to the failure of statistical patterns46. Process-driven models, built on physical processes such as precipitation interception and soil infiltration, can inherently reflect the logic of runoff formation with an irreplaceable ability to explain mechanisms47,48,49. Therefore, future research should promote the integration of the two, achieving synergy between “data capture” and “mechanism characterization”.

Overall, runoff forecasting remains a challenge. Although this study verifies the modeling capability of multi-scale autoregressive characteristics, nonlinearity, data heterogeneity, and extrapolation-based uncertainty remain the core challenges. Future studies should address the limitations of single-method approaches and integrate multiple hydrological characteristics to generate more accurate runoff predictions.

Conclusion

This study focused on multi-scale runoff time series predictions by discovering MSER in hydrological autoregressive characteristics. MSEIP was proposed, and a global runoff time series prediction model covering 18,250 hydrological stations was established for the case studies. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

An MSER characteristic exists in the hydrological time series, and its applicability is constrained by the flow scale: the larger the average flow rate, the higher the applicability of the characteristic. Through analysis of the multiple correlation coefficients of 18,250 global stations, the proportion of stations exhibiting this characteristic accounted for 0.51, 0.74, and 0.96 of the total stations with flow rates less than 100 m3/s, 100–2000 m3/s, and greater than 2000 m3/s, respectively, showing a significant upward trend.

-

(2)

Compared with the DPL method, as the time scale increased, the proportion of stations with improved prediction effects by the MSEIP method gradually decreased. The OPMAE of MSEIP-w reached 0.99, and even the worst-performing OPME reached 0.94. However, for MSEIP-m, MSEIP-s, and MSEIP-y, the OPMAE values were 0.76, 0.70, and 0.60, respectively, showing a clear downward trend. On a weekly scale, the MSEIP method significantly improved the accuracy of runoff prediction.

-

(3)

Compared with the DPL method, as the runoff flow rate increased from low to high, the proportion of stations with improved prediction effects by the MSEIP method gradually increased. At MSEIP-m, among stations with flow rates of 0–100 m3/s, the OPQR index is 0.60; among stations with flow rates of 100–2000 m3/s, the OPQR value rises to 0.64, and among stations with flow rates greater than 2000 m3/s, the OPQR index reaches 0.85, showing a clear upward trend.

-

(4)

Compared with linear models such as MLR, nonlinear models such as GPR exhibit a stronger ability to capture MSER characteristics at long time scales. For 24 selected stations where the MLR model shows poor prediction performance, GPR achieved OPQR values of 0.67 and 0.58 at the seasonally and yearly scales, respectively, while those of the MLR model were only 0.29 and 0.21. However, the high computational complexity of GPR leads to over-smoothing of daily scale data. At the weekly scale, except for OPQR being 1 (superior to MLR), all other GPR indicators were worse than those of the MLR model. This suggests that MLR has a stronger ability to capture the MSER characteristic at small time scales, whereas the GPR nonlinear model demonstrates more obvious advantages at large time scales.

Data availability

The streamflow observation data for over 20,000 rivers worldwide (1979–2013) used in this study are derived from the paper: https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025287. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, F., Ma, G., Ju, C., Chen, S. & Huang, W. Data-driven forecasting framework for daily reservoir inflow time series considering the flood peaks based on multi-head attention mechanism. J. Hydrol. 645, 132197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.132197 (2024).

Guo, J. et al. Study on optimization and combination strategy of multiple daily runoff prediction models coupled with physical mechanism and LSTM. J. Hydrol. 624, 129969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129969 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. A hybrid model coupling process-driven and data-driven models for improved real-time flood forecasting. J. Hydrol. 638, 131494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131494 (2024).

Chen, J. & Adams, B. J. Integration of artificial neural networks with conceptual models in rainfall-runoff modeling. J. Hydrol. 318, 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.06.017 (2006).

Li, H., Zhang, C., Chu, W., Shen, D. & Li, R. A process-driven deep learning hydrological model for daily rainfall-runoff simulation. J. Hydrol. 637, 131434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131434 (2024).

Bhasme, P., Vagadiya, J. & Bhatia, U. Enhancing predictive skills in physically-consistent way: Physics informed machine learning for hydrological processes. J. Hydrol. 615, 128618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128618 (2022).

Wei, X., Wang, G., Schmalz, B., Hagan, D. F. T. & Duan, Z. Evaluation of transformer model and self-attention mechanism in the Yangtze River basin runoff prediction. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 47, 101438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101438 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. A physical process and machine learning combined hydrological model for daily streamflow simulations of large watersheds with limited observation data. J. Hydrol. 590, 125206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125206 (2020).

Sabzipour, B. et al. Comparing a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network with a physically-based hydrological model for streamflow forecasting over a Canadian catchment. J. Hydrol. 627, 130380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130380 (2023).

Chu, H., Wu, J., Wu, W. & Wei, J. A dynamic classification-based long short-term memory network model for daily streamflow forecasting in different climate regions. Ecol. Ind. 148, 110092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110092 (2023).

Zhang, J. & Yan, H. A long short-term components neural network model with data augmentation for daily runoff forecasting. J. Hydrol. 617, 128853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128853 (2023).

Moosavi, V., Gheisoori Fard, Z. & Vafakhah, M. Which one is more important in daily runoff forecasting using data driven models: Input data, model type, preprocessing or data length?. J. Hydrol. 606, 127429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127429 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Bias learning improves data driven models for streamflow prediction. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 50, 101557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101557 (2023).

Yang, M., Yang, Q., Shao, J., Wang, G. & Zhang, W. A new few-shot learning model for runoff prediction: Demonstration in two data scarce regions. Environ. Model. Softw. 162, 105659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2023.105659 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Research on runoff process vectorization and integration of deep learning algorithms for flood forecasting. J. Environ. Manag. 362, 121260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121260 (2024).

Weng, P., Tian, Y., Liu, Y. & Zheng, Y. Time-series generative adversarial networks for flood forecasting. J. Hydrol. 622, 129702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129702 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Daily runoff forecasting by deep recursive neural network. J. Hydrol. 596, 126067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126067 (2021).

Yao, Z., Wang, Z., Wang, D., Wu, J. & Chen, L. An ensemble CNN-LSTM and GRU adaptive weighting model based improved sparrow search algorithm for predicting runoff using historical meteorological and runoff data as input. J. Hydrol. 625, 129977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129977 (2023).

Huan, S. Geographic heterogeneity of activation functions in urban real-time flood forecasting: Based on seasonal trend decomposition using loess-temporal convolutional network-gated recurrent unit model. J. Hydrol. 636, 131279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131279 (2024).

Tang, Z. et al. Improving streamflow forecasting in semi-arid basins by combining data segmentation and attention-based deep learning. J. Hydrol. 643, 131923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131923 (2024).

Champaneria, M. et al. Empirical evaluation of deep learning based models for time series datasets. Proc. Comput. Sci. 230, 864–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2023.12.046 (2023).

Zou, Y., Wang, J., Lei, P. & Li, Y. A novel multi-step ahead forecasting model for flood based on time residual LSTM. J. Hydrol. 620, 129521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129521 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Mid- to long-term runoff prediction based on deep learning at different time scales in the Upper Yangtze River Basin. Water. 14 (2022).

Feng, Z.-K., Niu, W.-J., Tang, Z.-Y., Xu, Y. & Zhang, H.-R. Evolutionary artificial intelligence model via cooperation search algorithm and extreme learning machine for multiple scales nonstationary hydrological time series prediction. J. Hydrol. 595, 126062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126062 (2021).

Wen, X. et al. Two-phase extreme learning machines integrated with the complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise algorithm for multi-scale runoff prediction problems. J. Hydrol. 570, 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.12.060 (2019).

Rahmani, F. & Fattahi, M. H. Association between forecasting models’ precision and nonlinear patterns of daily river flow time series. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 4267–4276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01351-4 (2022).

Rahmani, F. & Fattahi, M. H. Investigation of denoising effects on forecasting models by statistical and nonlinear dynamic analysis. J. Water Clim. Change 12, 1614–1630. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2020.014 (2020).

Gaertner, B. Geospatial patterns in runoff projections using random forest based forecasting of time-series data for the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169211 (2024).

Cao, C., He, Y. & Cai, S. Probabilistic runoff forecasting considering stepwise decomposition framework and external factor integration structure. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121350 (2024).

Xu, Z., Mo, L., Zhou, J., Fang, W. & Qin, H. Stepwise decomposition-integration-prediction framework for runoff forecasting considering boundary correction. Sci. Total Environ. 851, 158342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158342 (2022).

Lecun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 86, 2278–2324. https://doi.org/10.1109/5.726791 (1998).

Cheng, W. et al. High-efficiency chaotic time series prediction based on time convolution neural network. Chaos Solitons Fractals 152, 111304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111304 (2021).

Zhou, R. & Zhang, Y. Linear and nonlinear ensemble deep learning models for karst spring discharge forecasting. J. Hydrol. 627, 130394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130394 (2023).

Chang, X. et al. Study on runoff forecasting and error correction driven by atmosphere–ocean-land dataset. Expert Syst. Appl. 263, 125744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125744 (2025).

Sahoo, S. & Jha, M. K. Groundwater-level prediction using multiple linear regression and artificial neural network techniques: a comparative assessment. Hydrogeol. J. 21, 1865–1887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-013-1029-5 (2013).

Lei, X., Yang, J., Wang, C., Zhongzheng, H. E. & Liu, Q. Research on efficiency simulation model of pumping stations based on data-driven methods. Energy Rep. 12, 2773–2785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2024.08.048 (2024).

Madhushani, C. et al. Modeling streamflow in non-gauged watersheds with sparse data considering physiographic, dynamic climate, and anthropogenic factors using explainable soft computing techniques. J. Hydrol. 631, 130846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.130846 (2024).

Jahangir, M. S., You, J. & Quilty, J. A quantile-based encoder-decoder framework for multi-step ahead runoff forecasting. J. Hydrol. 619, 129269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129269 (2023).

Niu, W.-J. & Feng, Z.-K. Evaluating the performances of several artificial intelligence methods in forecasting daily streamflow time series for sustainable water resources management. Sustain. Cities Soc. 64, 102562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102562 (2021).

Lin, P. et al. Global reconstruction of naturalized river flows at 2.94 million reaches. Water Resour. Res. 55, 6499–6516. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025287 (2019).

Chen, P. et al. Pathformer: multi-scale transformers with adaptive pathways for time series forecasting (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. The role of matching pursuit algorithm and multi-scale daily rainfall data obtained from decomposition in runoff prediction. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 53, 101836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101836 (2024).

Naganna, S. R., Marulasiddappa, S. B., Balreddy, M. S. & Yaseen, Z. M. Daily scale streamflow forecasting in multiple stream orders of Cauvery River, India: Application of advanced ensemble and deep learning models. J. Hydrol. 626, 130320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130320 (2023).

Todorović, A., Grabs, T. & Teutschbein, C. Improving performance of bucket-type hydrological models in high latitudes with multi-model combination methods: Can we wring water from a stone?. J. Hydrol. 632, 130829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.130829 (2024).

Ng, K. W. et al. A review of hybrid deep learning applications for streamflow forecasting. J. Hydrol. 625, 130141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130141 (2023).

Jiang, S., Zheng, Y., Wang, C. & Babovic, V. Uncovering flooding mechanisms across the contiguous United States through interpretive deep learning on representative catchments. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR030185. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030185 (2022).

Vansteenkiste, T. et al. Intercomparison of five lumped and distributed models for catchment runoff and extreme flow simulation. J. Hydrol. 511, 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.01.050 (2014).

Lu, K., Cui, T., Wang, Y., Liu, Y. & Ma, X. Prediction of future runoff in the Lancang River Basin based on CMIP6 under climate change. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 59, 102413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2025.102413 (2025).

Jia, L., Niu, Z., Sun, D. & Liang, S. Quantifying the effects of driving factors and runoff sensitivity on runoff variation based on the Budyko equation. Ecol. Ind. 175, 113555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2025.113555 (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2240203, 52209024, 42271044, 52394234), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province, China (20243BCE51170), and the Project of Fundamental Research Funds for Central Public Welfare Scientific Research Institutes (2024AFA011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. and J.L. designed and conducted the experiments, wrote the draft of the paper and prepared the figures for this paper. Z.H., Y.W. and C.W. proposed the main structure of this study. T.Z., J.G., C.J. and H.Q. provided useful advice and made some corrections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The author promises to comply with the Ethical Standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The participants have consented to the submission of the research article to the journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Z., Lu, J., Wang, Y. et al. Multi-scale effects of runoff time series and its improved prediction methods. Sci Rep 15, 31873 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17207-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17207-7