Abstract

This study investigates the linear and nonlinear optical properties of La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ (x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5) thin films, prepared via electron beam evaporation. Structural and morphological characterizations were performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), confirming a layered perovskite structure. UV-Vis spectroscopy revealed a decrease in optical band gap from 3.25 eV (x = 0.5) to 2.25 eV (x = 0.9), followed by irregular variations for x > 0.9. Nonlinear optical properties, assessed via Z-scan, showed peak nonlinear absorption (14.57 × 10⁻⁵ cm/W) and refractive index (9.32 × 10⁻⁵ cm²/W) at x = 0.9, attributed to enhanced Co³⁺ populations. These properties make La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ thin films promising for photonic devices, such as optical switches and modulators, offering advantages over nanoparticles due to improved crystallinity and tunable optical responses. This work advances the understanding of Sr doping effects on Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites for optoelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear optical (NLO) materials are essential for advancing modern optoelectronic and photonic technologies, enabling applications such as optical switches, frequency converters, optical limiters, and high-speed telecommunications devices1,2. These materials exhibit complex interactions with intense light, allowing manipulation of optical signals through phenomena like second-harmonic generation (SHG), two-photon absorption (TPA), and nonlinear refraction3. Among the diverse classes of NLO materials, Ruddlesden-Popper (R-P) perovskites, with their layered structure of general formula Aₙ₊₁BₙX₃ₙ₊₁, have attracted significant attention due to their tunable electronic, optical, and magnetic properties, which arise from the interplay of perovskite and rock-salt layers4,5. These properties make them ideal candidates for optical devices such as modulators, and frequency converters. The tunable bandgap and high absorption coefficient of these perovskite materials further enhance their potential for use in nonlinear optical applications5,6. Additionally, their low cost and ease of fabrication enhance their commercial viability in the field of nonlinear optics.

Moreover, the reduced dimensionality in these materials can significantly increase their nonlinear optical properties. This enhancement can be attributed to the confinement of charge carriers within the low-dimensional structures, leading to increased optical nonlinearities.

Overall, the investigation of two-dimensional R–P halide perovskites and other perovskite oxide materials as nonlinear optical materials reveals the promising potential for optical applications. The distinctive properties of these materials, including their direct band gap, excitonic effects, and two-photon absorption, make them attractive candidates for various nonlinear optical applications. Further research and development in this field could facilitate advancements in nonlinear optical devices and technologies. La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄, a prototypical R-P perovskite, is particularly promising due to its tunable band gaps, insulator-to-metal transitions, and significant NLO responses driven by Sr doping and Co spin-state transitions6,7,8.

Previous research on La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ has predominantly focused on nanoparticles, which have demonstrated tunable optical band gaps (e.g., 4.25 eV to 3.65 eV for x = 0.5 to 0.9) and enhanced NLO properties, attributed to strong hybridization between Co-3d and O-2p orbitals and Co³⁺ spin-state transitions from low-spin (LS) to intermediate-spin (IS) states9,10. However, nanoparticle-based systems face challenges, including aggregation, surface defects, and limited stoichiometric control, which restrict their performance in practical optoelectronic devices9,11. For instance, studies have shown that nanoparticle aggregation can lead to inconsistent optical properties, while high processing temperatures in conventional synthesis methods, such as solid-state or standard sol-gel techniques, often result in inhomogeneity and phase impurities12,13. In contrast, thin films offer superior crystallinity, uniformity, and compatibility with device fabrication, making them ideal for applications requiring precise optical and structural control14.

The development of high-quality thin films is critical to overcoming these limitations and unlocking the full potential of R-P perovskites. Recent studies on related perovskite materials, such as halide perovskites and oxide-based R-P phases, have highlighted their promise in solar cells, photodetectors, and photocatalysis, driven by high absorption coefficients and tunable band gaps5,15,16. However, the nonlinear optical properties of La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ thin films remain underexplored, despite their potential to outperform nanoparticles due to reduced surface defects and enhanced structural order17. The electron beam evaporation technique, which enables precise control over film thickness and stoichiometry, represents a significant advancement over traditional methods, offering homogeneous films with improved optical properties at lower processing temperatures12,18.

In this research, optical and structural properties of La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ (x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5) thin films are characterized using XRD, UV-Vis spectroscopy, Z-scan, FE-SEM, AFM, and EDS analyses. Unlike previous studies focusing on La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ nanoparticles9,11, this work investigates thin films prepared via electron beam evaporation, offering improved crystallinity, controlled stoichiometry, and enhanced optical properties due to the modified sol-gel synthesis and deposition method. This study provides a systematic analysis of Sr doping effects on linear and nonlinear optical responses, revealing optimal performance at x = 0.9, which is critical for applications in photonic devices such as optical switches and modulators. By addressing the limitations of conventional synthesis methods (e.g., inhomogeneity and high processing temperatures), this work contributes to the development of high-performance Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite thin films for optoelectronics.

Experimental procedure

Synthesis

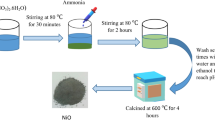

La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ (where x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5) nanopowders were synthesized using a modified sol-gel methods12. High-purity nitrate precursors-La(NO₃)₃·6 H₂O (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99.0%), Sr(NO₃)₂ (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99.0%), and Co(NO₃)₂·6 H₂O (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 98%)-were employed as starting materials. In order to synthesize 1 gr La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ (x = 0.5) nanopowders, 1.731 gr La(NO₃)₃·6 H₂O, 0.282 gr Sr(NO₃)₂, and 0.776 gr Co(NO₃)₂·6 H₂O were employed as starting materials. Also, 1.542, 1.343, 1.131, 0.907, and 0.660 gr of La(NO₃)₃·6 H₂O, 0.406, 0.537, 0.671, 0.823, and 0.982 gr of Sr(NO₃)₂, and 0.797, 0.820, 0.845, 0.870, and 0.899 gr of Co(NO₃)₂·6 H₂O were used as precursors to synthesize La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ with x = 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5, respectively. The weighed nitrates were dissolved in a deionized water, under continuous magnetic stirring at room temperature to ensure complete dissolution. Gelatin, as the polymerization agent, was separately dissolved in deionized water and stirred at 60 ℃ for 30 min. Afterward, the ion contained solution was added to aqueos solution of gelatin and heated to 80 °C in an oil bath, under vigorous stirring to evaporate excess water, leading to the formation of a viscous resin. The resulted resin was then heated to 220 °C for 1 h, during which the resin transformed into a black, porous powder. This step ensures the removal of residual water and the decomposition of organic components. Finally, the black precursor powder was subsequently ground and then calcined at 900 °C for 4 h in air, with a heating rate of 4 °C/min.

Thin film preparation method

To prepare thin films using Electron beam evaporation which is a widely used technique for depositing thin films onto substrates(glass). The electron beam evaporator was used to heat and vaporize the material using an electron beam. A vacuum environment was required for the deposition process to prevent contamination and oxidation. The chamber was evacuated to a high vacuum, typically in the range of 10−6 Torr. This prevented contamination and oxidation during deposition. The pressure was maintained at the desired level throughout the process.

The material to be deposited was placed in the evaporator’s crucible or source. Both the substrate and material source were inserted into the vacuum chamber. Prior to deposition, the substrate (typically glass or silicon, here glass) was carefully cleaned using a multi-step protocol. First, it was ultrasonically cleaned in acetone for 10 min, followed by a similar treatment in isopropanol. The substrate was then rinsed thoroughly with deionized water and dried using a nitrogen gas stream. This process ensured the removal of organic contaminants, grease, and surface oxides. After cleaning, the substrate was mounted on a rotating substrate holder to promote uniform thin film growth. The rotation speed was maintained at approximately 10 revolutions per minute (rpm), based on standard practices reported previously18.

The electron beam was directed at the material in the crucible. The material was heated by the electron beam until it vaporized. The material evaporated, and atoms or molecules traveled toward the cooler substrate. The high energy of the electron beam caused the material to vaporize and condense on the substrate surface. The evaporation rate was controlled by adjusting the electron beam power, typically ranging from 1.5 kW to 3 kW, depending on the material being evaporated. In this method a flux of vapor was in a based pressure (10−6 bar) without any catalyst. The current value for \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) are 200 A, 150 A, 170 A, 190 A, 200 A, and 160 A for x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5, respectively. The used power is 2, 1.5, 1.7, 1,9, 2, and 1.6 kW respectively. The power was regulated using a 10 V accelerating potential applied to a heated filament. The deposition rate was monitored using a quartz crystal microbalance, and maintained between 1 and 3 Å/s18. After the film was deposited, the substrate was cooled to room temperature, slowly. Rapid cooling was avoided to prevent film stress, cracking, or poor adhesion which are briefly illustrated in Ref No. 1919.

Characterization methods

The synthesized thin films were characterized using an X-ray diffractometer with a certain device (XRD Philips PW1730 with a copper lamp, voltage: 40 kV, Electric current: 30 mA, λ = 1.540598 Å) located in Mahamax Co. The morphological properties of thin films were characterized by a microscope (FE-SEM: TE-SCAN, MIRA3). The UV-VIS of the synthesized thin films was acquired using a spectrophotometer, UV-VIS Thermo Biomate 5 using different wavelengths in the range of 100 nm until 1000 nm.

The analysis of nonlinearity: the Z-scan theory

Z-scan method has quickly become a widely accepted standard technique in the nonlinear optics community for independently determining the nonlinear variations in both the refractive index and absorption18. This widespread acceptance is primarily due to the simplicity of the technique as well as the ease of data interpretation. In most experiments, the refractive index changes (∆n) and the absorption coefficient changes (∆α) could be directly determined by the data without needing computer fitting. However, it is important to acknowledge that this method is sensitive to all nonlinear optical mechanisms that cause variations in the refractive index and/or absorption coefficient, making it generally impossible to identify the specific underlying physical processes present from a Z-scan alone. In the case of negative nonlinearity, the Z-scan signal exhibits a peak-valley at the data transmittance9. On the other hand, positive nonlinearity is characterized by a valley-peak configuration in the Z-scan graph.

The setup for Z-scan tests involved a CW Nd: YAG laser at 532 nm with 40 mW power. A positive lens (f = 19 cm) was used to focus the Gaussian beam, resulting in a beam waist of 36 μm at the focus and a Rayleigh length of 9.4 mm. \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin film was moved across the focal region along the main axis direction propagation of laser. This experimental setup allowed for the accurate nonlinearity characterization of the\(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin film.

Results and discussion

XRD characterization

XRD graphs of the \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{s}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin films are illustrated in Fig. 1. Accordingly, it has three main peaks in the region of 10 degrees to 70 degrees. The diffraction peaks of the sample are given in Table 1. The main peaks were indexed and correspond to the (101), (004), (103), (110), (200), (211), (215), and (208) planes, confirming the formation of a layered perovskite-like structure6.

The average particle size in lanthanum strontium cobalt oxide () with different x determined using the Debye-Scherr relationship and XPert software, is presented in Table 1. The third column of this table specifically details the particle sizes corresponding to different x values. The crystallinity index and mean crystallite size of the La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ samples were calculated from the XRD data using the Scherrer equation. As the Sr content increased, variations in the crystallinity index and FWHM were observed, indicating changes in the structural order. Generally, higher crystallinity indices were associated with sharper peaks and larger crystallite sizes. These results suggest that Sr doping plays a key role in modifying the crystal structure and particle size of the synthesized materials.

For the sample with a higher La content (x = 0.5) in \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) (x = 0.5–1.5) it is expected that the predominant ionic species would be \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{2+}\), while for x more than one, a large amount of Co ions will be present as \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{3+}\) and \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{4+}\). It can be concluded that increasing the concentration of \(\:{\text{S}\text{r}}^{2+}\)doping in \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\), results in a decrease in the value of the ionic radius at the Co sites, that is a dominant factor contributing to the reduction of unit cell parameters and volume. The detailed discussion of lattice parameter variations in La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ due to Sr doping has been provided in our previous publication9. Briefly, while the substitution of larger Sr²⁺ ions (1.30 Å) for La³⁺ (1.216 Å) might suggest an expansion of the unit cell, experimental results show a decrease in the lattice parameter a and unit cell volume with increasing Sr content. This trend is not solely explained by ionic radii differences, but rather by the increase in the average oxidation state of Co ions (from Co²⁺ to Co³⁺/Co⁴⁺), which reduces the average ionic radius at Co sites. Additionally, the non-linear variation in the c parameter, particularly its increase for 0.9 ≤ x≤1.3, is attributed to Jahn-Teller distortions caused by the presence of Co³⁺ ions in the intermediate spin (IS) state. At higher Sr levels (x = 1.5), the rise in Co⁴⁺ (LS) population leads to a contraction of the structure9. In related research, it can be observed that the lattice parameter a and the unit cell volume of La2−xSrxCoO4 decreased with the increase of Sr concentration. However, c parameter showed a nonlinear trend; it decreased for x < 1 and increased for x > 112,13. This trend observed in this research just the c parameter does not show any increasing or decreasing for x > 1.

XRD analysis of both La2−xSrxCoO4 nanoparticles and thin films reveals that while both exhibit the same crystalline phase, noticeable differences emerge in terms of peak width, intensity, and preferred orientation. The broader diffraction peaks observed in the nanoparticle samples suggest smaller crystallite sizes and possibly higher lattice strain. In contrast, the thin films typically display sharper peaks. Additionally, variations in peak intensity ratios in the thin films may reflect internal stress or anisotropic grain alignment. These differences underscore how the fabrication route not only affects the physical dimensions, but also significantly influences the crystal order and structural integrity of the final material.

FE-SEM analysis

Figure 2 presents FE-SEM micrographs of thin films deposited at various doping concentrations of Sr2+ from x = 0.5 to x = 1.5. As can be observed in Fig. 2, the particles with x = 0.9 exhibits the largest size. In contrast with previous research, an increase in the doping concentration of more than x = 0.9 results in a reduction of particle size. In previous research, it can be observed that there was no significant difference in the size and the morphology between minimum (x = 0.5) and maximum (x = 1.5) doping concentrations of Sr2+9. The average particle size was found below 100 nm in which confirmed by previous research9. Additionally, FE-SEM imaging was conducted to assess the thin films thickness for various x values, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

As shown in Fig. 3, x = 0.9 exhibits the largest film thickness; however, the largest particle (crystal) size is observed for the sample with x = 0.9, as confirmed by SEM analysis. The particle size and its distribution were quantitatively analyzed using SEM images, and the data were fitted with Gaussian functions (Fig. 4). The results are summarized in Table 2. Among all samples, the one with a doping level of 0.9 exhibits the largest average particle size of 55.07 nm, along with the widest full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 14.36 nm. The larger mean value indicates an increase in particle growth, while the broader FWHM suggests a more heterogeneous distribution of particle sizes.

This behavior may be attributed to the influence of dopant concentration on nucleation and growth mechanisms during the film formation process. Particularly, the sample with a 0.9 doping level demonstrates significant deviation in both size and uniformity compared to the other compositions, implying that this specific concentration strongly affects the microstructural evolution of the thin film.

UV-Vis spectra analysis

The most common techniques used to determine the optical band gap of materials are UV-Vis spectroscopy and Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS). UV-Vis spectroscopy is a method that measures the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by a material, typically used for transparent or thin film samples. DRS (Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy) is an analytical technique that measures the reflectance of a material as a function of wavelength, particularly suitable for powders and opaque samples. Both methods are often used with the Tauc plot approach to estimate the band gap energy. The UV-Vis spectra of \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) are illustrated in Fig. 5. These spectra provide insight into the samples’ optical properties and electronic structures. According to UV-Vis spectra, the absorption band broadens from the UV to visible region for x = 0.5 to 1.3 and 1.5. Also, the second peak absorption observe at 270 nm. The UV-Vis spectra of La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ thin films (Fig. 5) reveal sample-dependent absorption characteristics. Between 250 and 350 nm, a prominent absorption peak at ~ 270 nm is observed, with intensity varying across doping levels. This peak is attributed to charge-transfer transitions between O-2p and Co-3d orbitals, modulated by Sr-induced changes in Co oxidation states (Co²⁺ to Co³⁺/Co⁴⁺)9. The strongest absorption at x = 0.9 correlates with the largest particle size (55.07 nm, Table 2) and highest crystallinity (Table 1), suggesting enhanced orbital hybridization and reduced lattice strain, as confirmed by XRD. For x > 0.9, the absorption intensity decreases, likely due to Jahn-Teller distortions associated with Co³⁺ intermediate-spin states, which disrupt the electronic structure6.

From 400 to 600 nm, all samples exhibit increased absorption, likely due to d-d transitions of Co ions, which are less sensitive to doping but influenced by film thickness (508–551 nm, Table 2). Thicker films (e.g., x = 0.9, 551 nm) enhance light-matter interactions, increasing absorption. Particle size also plays a role, as larger particles at x = 0.9 reduce scattering losses, contributing to higher absorption. These trends align with prior studies on Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites, where similar absorption bands were reported due to charge-transfer and d-d transitions9. However, our thin films show stronger absorption than nanoparticles9, likely due to improved crystallinity and reduced surface defects.

To determine the band gap energy of (\(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\)), UV-Vis spectral data were used to construct a plot of (αhν)2 versus ℎ where α represents the linear absorption. The band gap energy was then obtained by extrapolating the linear portion of this curve. This method is consistent with previous studies that have employed similar techniques to analyze the optical properties of Ruddlesden-Popper phases8.

Figure 6 were indicated direct and indirect band gaps of \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin films determined using the Tauc relation9. Our calculations show no significant difference between the direct and indirect band gap energies. According to Fig. 6, the direct band gap energy of La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ thin films decreases from 3.25 eV (x = 0.5) to 2.25 eV (x = 0.9), then exhibits irregular variations (2.35 eV, 3.00 eV, and 2.50 eV for x = 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5, respectively). This trend is attributed to enhanced Co-3d and O-2p orbital hybridization with increasing Co³⁺ populations up to x = 0.9, which reduces the band gap by facilitating charge-transfer transitions9. For x > 0.9, Jahn-Teller distortions due to Co³⁺ intermediate-spin states disrupt the electronic structure, leading to irregular band gap changes13. XRD data (Table 1) confirm structural changes, with the highest crystallinity at x = 0.9 correlating with the lowest band gap.

Compared to nanoparticle studies9, which reported band gaps of 4.25 eV (x = 0.5) to 3.65 eV (x = 0.9), our thin films exhibit lower values (by ~ 1 eV). This difference arises from improved crystallinity, reduced surface defects, and stronger grain boundary interactions in thin films, as evidenced by sharper XRD peaks and SEM images (Fig. 2). Both nanoparticles and thin films show the lowest band gap at x = 0.9, indicating that this doping level optimizes electronic structure regardless of morphology. However, thin films offer advantages for optoelectronic applications due to their uniformity and tunable optical properties.

AFM characterization

Figure 7 illustrates two-dimensional (2D) AFM surface morphologies of \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin films with different Sr doping levels ranging from x = 0.5 to x = 1.5. As shown in Fig. 7, different doping of Sr influenced the histogram topographic profiles of thin films. An increase in Sr doping resulted in a transition from a smooth to a rough surface morphology characterized by larger grain sizes. As seen in the images, the surface morphology evolves noticeably with increasing Sr content. For lower doping levels (e.g., x = 0.5 and x = 0.7), the grains appear relatively uniform and well-defined.

Figure 8 illustrates the variation of root mean square (RMS) roughness and the average roughness (AR) with different Sr doping levels in \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\:\)thin films. As the doping level increases, both RMS and AR exhibit noticeable fluctuations. The RMS values show a peak at x = 0.9, indicating increased surface roughness, while the AR values remain relatively stable with a moderate upward trend. At x = 0.9, the surface roughness increases significantly, with larger and more irregular features—consistent with the RMS peak observed in the bar chart. As the doping continues to increase to x = 1.1, x = 1.3, and x = 1.5, the surface becomes slightly more compact again, though with some persistence of the granular texture. These morphological changes suggest that Sr doping has a strong impact on the growth dynamics and surface structure of the films. According to literature, these variations suggest that doping significantly influences the surface morphology and anisotropy of the films7.

EDS analysis

To confirm the elemental composition and verify the doping levels in \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) samples, Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS, Model: EDS SAMX Co. France) was performed on samples with various Sr concentrations (x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5). The measured weight and atomic percentages of La, Sr, Co, and O are summarized in Table 3. EDS analysis (Table 3) confirms the substitution of Sr for La, with increasing Sr wt% and decreasing La wt% as x increases from 0.5 to 1.5, except at x = 0.7 and x = 0.9. At x = 0.7, La wt% is 31.84% and Sr wt% is 17.96%, while at x = 0.9, La wt% is 33.38% and Sr wt% is 17.76%, deviating from the expected trend of decreasing La with increasing Sr. This anomaly may result from variations in film thickness (519 nm at x = 0.7, 551 nm at x = 0.9) or surface segregation during deposition, affecting EDS measurements. For other doping levels, the expected trend is observed, confirming successful doping. These findings align with prior studies12, though thin films show slight stoichiometric variations due to the evaporation process.

The results indicate a clear trend, with increasing Sr content (higher x values), the atomic and weight percentages of Sr increase, while those of La decrease correspondingly. This confirms the successful substitution of Sr for La in the crystal structure. Minor variations in the oxygen and cobalt contents may be attributed to structural adjustments or charge compensation mechanisms associated with Sr doping. Overall, the EDS data supports the expected stoichiometry and confirms that the doping was effectively achieved. Figure 9 exhibits EDS point chemical analysis spectra of the sample in which the chemical analysis confirms the stoichiometric composition as La2−xSrxCoO4.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) spectrum of \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\). shown as a plot of X-ray counts versus energy. Energy peaks corresponding to various elements in the sample are indicated in (a) x = 0.5, (b) x = 0.7, (c) x = 0.9, (d) x = 1.1, (e) x = 1.3, and (f) x = 1.5.

Nonlinear optical analysis

The nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin films were characterized by both open and closed-aperture Z-scan measurements via the nonlinear absorption coefficient and the nonlinear refraction coefficient, respectively21. By analyzing the Z-scan data, it was determined NLO properties of the \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) films. The focused laser onto the thin films by a lens, causes the Z-scan data were collected by moving the thin films along the Z-axis while monitoring the laser transmission through the specimen22.

The nonlinear absorption (NLA) determined using the following Eq8.:

where Leff =[(1-exp(αL))/α] is the effective length of the sample. By fitting the experimental data to these nonlinear absorption models, theoretical data by applying the following fitting equations verified experimental NLA findings17 :

Figure 10. presents the Z-scan plots of \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin films. The observed nonlinear absorption (NLA) is indicative of a TPA process. The symmetry of the curve around this focal point indicates that the TPA behavior begins to dominate over the NLA mechanism in the \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin film dispersions. Two-photon absorption (TPA), which is the simultaneous absorption of two photons, responses of La2−xSrxCoO4 thin films increased with the enhancement of Sr concentration from x = 0 until x = 0.9. Figure 11 illustrates the variation of normalized transmittance as a function of dopant content. The highest observed normalized transmittance is 14.57×\(\:{10}^{-5}\) (cm\(\:{W}^{-1}\)) for La1.1Sr0.9CoO4 and decreases to 9.9×\(\:{10}^{-5}\) (cm\(\:{W}^{-1}\)) for La0.5Sr1.5CoO4.

The NLO characteristics of the \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) films are tabulated in Table 4. The close aperture involved placing an aperture to capture data that includes NLR and NLA contributions. The pure NLR for the \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) presented in Fig. 11. This curve is characterized by a valley in the transmittance profile, indicative of a self-defocusing effect.

The localized absorption of the laser beam induces a spatially distributed temperature in the sample, leading to a spatial variation in refractive index. This refractive index variation acts as a thermal lens, causing the beam to defocus as it propagates through the sample. Consequently, the thermal nonlinearity effect leads to beam defocusing and phase distortions, which can adversely impact the quality and accuracy of the laser beam. This parameter depends on |\(\:{\varDelta\:\varnothing}_{0}\) | as shown23:

by the way, λ shows the laser wavelength and \(\:{I}_{0}\) = 19.65 × 104 W\(\:{cm}^{-2}\) is the input intensity. The experimental findings are in good agreement with the results reported by Sheikh Bahai. The following relation was used for fitting the experimental values of CA20.

In this study, the maximum value of the estimated NLR index \(\:{n}_{2}\)=−9.32×\(\:{10}^{-9}\) \(\:{cm}^{2}{W}^{-1}\) was determined for La1.1Sr0.9CoO4 through the closed aperture Z-scan analysis. Notably, as Sr doping values increased from x = 0.5 to 0.9 in \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\)thin films, NLA and NLR index increased. When the Sr doping value increased from 0.9 to 1.5, the nonlinearity responses decreased. The observed enhancement in nonlinear responses from x = 0.5 to 0.9 may be ascribed to an augmentation in the population concurrent with an escalation in Sr doping concentration. The pronounced hybridization between Co-3d and O-2p orbitals may elucidate this phenomenon, as it culminates in a more substantial enhancement of \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{3+}\)-LS populations relative to \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{2+}\)-HS populations with the increasing Sr doping from x = 0.5 to 0.9. It is established that \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{3+}\)-(LS) - O(2p) exhibits greater covalency compared to \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{2+}\)-(HS) - O(2p) for x < 19. This increased hybridization enhances the charge transfer mechanism that improves nonlinearity. Previous studies have indicated that enhancing the donor group such as (\(\:{\text{C}\text{o}}^{3+}\)) can increase the nonlinearity values, which further enhances nonlinear optical responses24.

The systematic analysis of n2 and β facilitates the evaluation of the real and imaginary components of the third-order NLO susceptibility (\(\:{\chi\:}^{3}\)), as elucidated by25:

Both real/imaginary parts and the absolute value of susceptibility are summarized in Table 5. NLO susceptibility has a critical role in interactions of light with matter and enhances our recognition of nonlinear optical characteristics11. Based on 2D quantum dot (T-QD) RP hybrid perovskite studies, significant nonlinear responses were observed in \(\:{\text{L}\text{a}}_{2-\text{x}}{\text{S}\text{r}}_{\text{x}}\text{C}\text{o}{\text{O}}_{4}\) thin films26.

Variations in thicknesses among samples have minimal impact on the magnitude of χ(3), which remains relatively stable across different samples, as presented in Table 5. At times, linear absorption causes a slight imbalance, thus, it is essential to evaluate this phenomenon using a figure of merit (FOM) parameter and decrease the imbalance as follows14 :

Moreover, Other critical factors must be considered when assessing the potential of various synthesized films for optical switching applications. Two principal parameters, W and T, delineate such characteristics in optical materials. The sample in which x = 0.9 exhibits T < 1 and W > 1, indicating its suitability as an optical switch device. W and T are introduced as27:

Compared to previous studies on La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ nanoparticles, our thin film samples exhibit a similar trend in optical behavior, where the nonlinear responses peak around x = 0.9, indicating a consistent effect of Sr doping across different morphologies24. Both studies demonstrated that the NLO properties, such as TPA coefficient, reached a maximum at x = 0.9. This consistency underscores the critical role of Sr-induced electronic structure modifications in enhancing optical nonlinearity. However, the TPA values observed in thin films (e.g., 14.57 × 10⁻⁵ cm/W) differ in magnitude from those reported in nanoparticle samples (e.g., 62.28 × 10⁻⁷ cm/W), which could be attributed to differences in material dimensionality, light-matter interaction depth, and microstructural effects9.

Conclusion

The structural, linear, and nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ thin films were systematically investigated through XRD, SEM, AFM, EDS, UV-Vis, and Z-scan analyses. Key parameters such as particle size, crystallite structure, surface roughness, optical band gap, and nonlinear response were all found to be significantly influenced by Sr doping. SEM analysis revealed that doping level x = 0.9 resulted in the largest particle size and greatest heterogeneity, suggesting enhanced particle growth and microstructural variation. AFM measurements showed a clear evolution from smooth to rough surface textures with increasing Sr content, again peaking at x = 0.9, highlighting its critical impact on surface morphology and growth behavior. EDS analysis confirmed the successful substitution of Sr for La across all samples, validating the intended stoichiometry and supporting the observed structural modifications.

Optical characterizations revealed a decrease in the band gap energy from 3.25 eV at x = 0.5 to 2.25 eV at x = 0.9. Correspondingly, the nonlinear optical responses also peaked at x = 0.9. Notably, the two-photon absorption coefficient reached a maximum transmittance value of 14.57 × 10⁻⁵ cm/W for x = 0.9, while the lowest value of 9.9 × 10⁻⁵ cm/W was recorded at x = 1.5. These findings can be attributed to enhanced Co-3d and O-2p orbital hybridization, driven by an increase in Co³⁺ low-spin (LS) populations up to x = 0.9. At higher Sr concentrations (x = 1.1–1.5), a transition of Co³⁺ ions from LS to intermediate-spin (IS) states—associated with the Jahn–Teller effect—leads to weaker Co³⁺–O(2p) hybridization and a corresponding decline in nonlinear optical performance. The results obtained from XRD, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and Z-scan measurements reveal significant differences between La2−xSrₓCoO₄ nanoparticles and thin films, despite their identical chemical composition. XRD patterns indicate smaller crystallite sizes and broader peaks in nanoparticles, whereas thin films exhibit improved crystallinity. Overall, these results suggest that La₂₋ₓSrₓCoO₄ thin films, particularly at x = 0.9, are promising candidates for photonic device applications.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Abdulhussein, H. A. et al. A comprehensive analysis of the structural, phonon, electronic, mechanical, optical, and thermophysical properties of cubic Ca3SbX3 (X = Cl, Br): DFT - GGA and mBJ studies. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 187, 109133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2024.109133 (2025).

Mohammed, M. K. A. et al. Harnessing the potential of Dion-Jacobson perovskite solar cells: insights from SCAPS simulation techniques. J. Alloys Compd. 963, 171246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171246 (2023).

Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear Optics 4th edn (Academic, 2020).

Xiao, W. Z., Huang, Z. S., Liu, P., Wang, W. & Ran, R. Ruddlesden–Popper perovskite oxides for photocatalysis-based water splitting and wastewater treatment. Energy Fuels. 34, 13203–13224. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02345 (2020).

Ghosh, A. et al. Investigating novel inorganic cubic perovskites A3BX3 (A = Ca, sr, B = P, as, X = I, Br) and their photovoltaic performance with efficiency over 28%. J. Alloys Compd. 986, 174097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.174097 (2024).

Ghorbani-Moghadam, T., Kompany, A., Bagheri-Mohagheghi, M. M. & Abrishami, M. E. Cobalt spin States investigation of Ruddlesden-Popper La2 – xSrxCoO4, using X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 465, 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.06.071 (2018).

Alattar, A. S., Nadafan, M., Dehghani, Z. & Khashehchi, M. Influence of d-d transition electrons and thickness variations on the excited-state optical properties: nonlinear optical characterization of Cr2O3 thin film. J. Lumin. 277, 120916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2024.120916 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Band gap evolution in Ruddlesden-Popper phases. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 101601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.3.101601 (2019).

Nadafan, M., Ghorbani-Moghadam, T. & Mousavi, M. Investigation of the linear and nonlinear optical properties of La2-xSrxCoO4 (x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3 and 1.5) nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 10443–10452. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1tc01982a (2021).

Liu, J. Optical fibers. In Photonic Devices 119–163 (Cambridge University Press, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511614255.004.

Varma, S. J. et al. Quantum Dots of two-dimensional Ruddlesden-Popper organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite with high optical limiting properties. AIP Adv. 10, 035008. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5142713 (2020).

Parashar, R., Shukla, M. & Singh, V. K. Metal oxides nanoparticles via sol–gel method: a review on synthesis, characterization and applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31, 3729–3749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-020-02994-8 (2020).

Tong, M. W., Xu, Y. L., Zhou, F., Yang, S. & Zhong, S. Performance and stability of Ruddlesden–Popper La2NiO4 + δ oxygen electrodes under solid oxide electrolysis cell operation conditions. Ceram. Int. 43, 12842–12847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.06.174 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enhanced Kerr nonlinearity and nonlinear figure of merit in silicon nanowires integrated with 2D graphene oxide films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 45804–45813. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c11296 (2020).

Kumar, A. et al. Calotropis-mediated biosynthesis of TiO2@SnO2/Ag nanocomposites for efficient perovskite photovoltaics. Opt. Mater. 151, 115402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.115402 (2024).

Wang, L. G. et al. Composition-dependent optical limiting behavior of all-inorganic halide perovskite quantum Dots. Opt. Mater. 108, 110183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110183 (2020).

Baishya, K., Ray, J. S., Dutta, P., Das, P. P. & Das, S. K. Graphene-mediated band gap engineering of WO3 nanoparticle and a relook at Tauc equation for band gap evaluation. Appl. Phys. A. 124, 704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-018-2097-0 (2018).

Van Stryland, E. W., Hagan, D. J. & Wu, Y. Z-scan. In Handbook of Optics, Volume IV: Optical Properties of Materials, Nonlinear Optics, Quantum Optics 3rd edn (McGraw-Hill, 2010).

Ijaz, I., Gilani, E., Nazir, A. & Bukhari, A. Detail review on chemical, physical and green synthesis, classification, characterizations and applications of nanoparticles. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 13(3), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2020.1802517 (2020).

Sheik-Bahae, M., Said, A. A., Wei, T. H., Hagan, D. J. & Van Stryland, E. W. Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 760–769. https://doi.org/10.1109/3.53394 (1990).

Smith, D. D. et al. Z-scan measurement of the nonlinear absorption of a thin gold film. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 6200–6205. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.371675 (1999).

Mousavi, M., Nadafan, M. & Yousefi, S. T. Third-order optical nonlinear properties of Co-doped V2O5 nanoparticles. Optik 242, 167053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167053 (2021).

Konwar, S. Optimizing the performance of an astigmatic defocus sensor and its implementation using computer generated hologram. ArXiv 230109054. https://doi.org/10.48550/ArXiv.2301.09054 (2023).

Katz, H. E. et al. Greatly enhanced second-order nonlinear optical susceptibilities in donor-acceptor organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 6561–6563. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00255a079 (1987).

Konwar, S. Astigmatic defocus sensor: its performance and optimization. J. Opt. 53, 3463–3475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12596-023-01562-7 (2024).

Wang, L. G., Li, W. C., Wang, T. & Zheng, C. Composition-dependent optical limiting behavior of all-inorganic halide perovskite quantum Dots. Opt. Mater. 108, 110183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110183 (2020).

Khorrami, G. A. M. A., Nadafan, M., Dehghani, Z. & Izadi-Darbandi, A. Green synthesis, crystal structure, linear and nonlinear optical investigation of MgO1-xMnOx nanocomposite via Z-scan technique. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 142, 109689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109689 (2022).

Funding

The authors sincerely appreciate the support provided by Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, under contract number 1404/395145, Tehran, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ Contribution Ali Reza Khalili: Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Ammar S. Alattar: Methodology, Writing–review & editing, Formal analysis. Tahereh Ghorbani-Moghadam: Writing–review & editing, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization. Marzieh Nadafan: Data curation, Visualization, writing – original draft, Writing–review & editing, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalili, A.R., Alattar, A.S., Ghorbani-Moghadam, T. et al. Investigation of optical properties in La2−xSrxCoO4 (x = 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5) thin films: a focus on the linear and nonlinear responses. Sci Rep 15, 34386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17244-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17244-2