Abstract

Intravenous catheter insertion is the most common procedure in the hospital setting and causes significant pain and anxiety for hospitalized children. This randomized controlled trial aimed to compare the effects of stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing on pain and anxiety levels during intravenous catheter insertion in hospitalized school-aged children. Ninety children aged 6–12 years admitted to the pediatric wards of Namazi Hospital in Shiraz, Iran, between May and September 2024, were randomly assigned to three groups: a stress ball group, a pinwheel group, and a control group. Pain and anxiety were assessed before, during, and after the procedure using the Oucher Pain Scale and the Venham Picture Test (VPT), respectively. The pinwheel group reported the lowest mean pain score (8.0 ± 11.3), followed by the stress ball group (14.5 ± 14.9) and control group (50.5 ± 34.6), with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Similarly, anxiety scores were lowest in the pinwheel group (0.7 ± 1.1), compared to the stress ball group (1.0 ± 1.2) and the control group (4.9 ± 2.8) (p < 0.05). Both interventions were effective, but pinwheel blowing showed greater reductions in pain and is recommended as a simple, low-cost distraction method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Illness and hospitalization often serve as a child’s first major crisis, causing significant stress due to changes in their health and environment1. Children generally have limited coping skills, which makes it difficult for them to handle these stressors, especially during painful procedures such as intravenous (IV) catheter insertion, one of the most common and distressing experiences in hospitals2,3,4.

Uncontrolled procedural pain in children can lead to long-term effects, such as needle phobia and avoidance of medical care in adulthood5,6. It can also harm the nurse-child relationship and decrease the child’s cooperation during treatment7.

While medications for pain and anxiety can be effective, they may cause side effects, including drowsiness, respiratory problems, confusion, and issues involving the kidneys, liver, or digestive system. Additionally, these treatments may lead to dependence and addiction8,9. Nonpharmacological pain management techniques are generally easy to implement, cost-effective, time-efficient, and free from side effects10,11,12. For this reason, nonpharmacological methods are often preferred for managing pain and anxiety in children13,14. Distraction is among the most effective non-drug strategies, shifting the child’s focus from painful stimuli to more pleasant experiences4,15. Techniques such as playing video games, watching animations, listening to music, blowing bubbles, and engaging in therapeutic play can stimulate children’s senses and help reduce their perception of pain16,17,18.

School-aged children (ages 6–12) possess sufficient cognitive maturity to utilize distraction techniques, particularly those involving multiple senses that pique their curiosity and encourage participation19. Pinwheel blowing and stress ball squeezing are simple, affordable, and engaging methods that can help reduce pain perception by competing with sensory pain signals during invasive procedures6,19,20,21. Although both techniques have been shown to effectively manage pain, fear, and anxiety in various medical settings, previous studies have examined them separately and have not explicitly focused on intravenous catheter insertion. Additionally, no randomized controlled trials have directly compared these two methods.

Objectives.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the effects of stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing on pain and anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion in hospitalized school-aged children.

Six hypotheses are proposed:

H1. The stress ball squeezing group will have less pain during intravenous catheter insertion compared to the control group.

H2. The Stress ball squeezing group will have less anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion compared to the control group.

H3. The pinwheel blowing group will have less pain during intravenous catheter insertion compared to the control group.

H4. The pinwheel blowing group will have less anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion compared to the control group.

H5. Stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing have different effects on the average pain scores resulting from intravenous catheter insertion in school-aged children.

H6. Stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing have different effects on the average anxiety scores resulting from intravenous catheter insertion in school-aged children.

Methods

Study design

This study was a prospective, three-arm, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial (RCT). This study was conducted among school-aged children aged 6–12 years admitted to the pediatric wards of Namazi Hospital in Shiraz, Iran, who required intravenous catheter insertion between May 1, 2024, and September 21, 2024.

Study population and sample

Considering a type I error of 0.05, a study power of 80%, and an effect size of 0.35 based on the pain and anxiety variable in the study by Lilik Lestari et al.22. Using G*Power software version 3.1.9.2 with an ANOVA test, the total sample size was calculated to be 81 participants (27 per group). Accounting for a 20% dropout rate in each group, the final sample size was estimated at 99 participants (33 per group). The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: children of both sexes aged 6 to 12 years; no pain other than that caused by intravenous catheter insertion; a minimum of six hours since hospitalization; no mental retardation, communication impairment, or loss of consciousness; no urgent need for intravenous catheter insertion; no seizures or life-threatening emergencies such as acute cardiac or respiratory conditions; no use of narcotics, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sedatives, local or general anesthesia, or anticonvulsants within the past 24 h; no neuropathic diseases; and the presence of a parent during the procedure. The exclusion criterion was parental unwillingness to participate in the intervention.

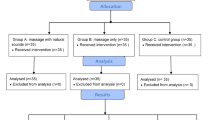

In this study, 157 children were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 58 were excluded for the following reasons: 6 did not agree to participate; 17 had pain unrelated to intravenous catheter insertion; 3 had intellectual disabilities, communication difficulties, or impaired consciousness; 28 had received narcotics, analgesics, NSAIDs, sedatives, local or general anesthesia, or anticonvulsants within the past 24 h; and four had been hospitalized for less than six hours. Overall, 99 children were randomized using block randomization software (with a 1:1:1 allocation ratio) into three groups: a stress ball group, a pinwheel group, and a control group. Nine children discontinued the intervention. A total of 90 children were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Data collection tools

The research data were collected via the ‘Demographic information questionnaire’, the ‘Oucher’ for Pain Assessment, and the ‘Venham’ for Anxiety Assessment.

Demographic information form

The demographic information form, consisting of 16 questions, was approved by pediatric nursing faculty members. It included questions about the child’s age, gender, mother’s age, mother’s education, father’s age, father’s education, child’s birth rank, family residence, child’s history of hospitalization and number of hospitalizations, date of child’s current hospitalization, child’s history of previous intravenous line placement, history of any needle insertion such as an ampoule or blood sampling, child’s sibling’s hospitalization history, location of intravenous line placement, parent who was with child when intravenous line was placed, and angiocatheter size.

Oucher pain scale

The Oucher Pain Self-Report Tool was developed by Beyer in 1984 to assess the severity of pain in children aged 3 to 12 years. This tool is one of the most reliable, oldest, and widely used self-reported pain intensity scales, which utilizes children’s faces in painful situations. This tool is used by child health professionals worldwide, and its content and construct validity have been documented through validity and reliability tests. This tool uses pictures of regular and distressed children’s faces that were taken from real children’s faces while experiencing real pain in the hospital. This tool includes six images of children showing different degrees of pain, arranged vertically from the least to the most severe, which can be converted into scores of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100. Children indicate the severity of their pain based on images of their faces. A picture of a child’s face without pain is given a score of zero, mild pain is given a score of 20, moderate pain is given a score of 40 or 60, severe pain is given a score of 80, and very severe pain is given a score of 100. A vertical table with numbers from 0 to 100 is also placed to the left of the picture23. The Oucher is a robust measure for the Iranian population. It has been validated and found to be reliable through various methods. Its reliability has been reported to be greater than 0.8 by multiple methods24,25,26.

Venham picture test

The Venham Picture Test is a self-reporting tool for determining anxiety, developed in 1979 by Venham and Gaulin-Kremer; it utilizes 8 picture cards. On each card, two pictures are drawn, one of which is anxious and the other of which is nonanxious. The eight cards are presented to the child sequentially, one at a time. He is asked which of the two pictures best expresses his inner feelings. If the child chooses the anxious picture, his anxiety score will be 1, and if the child chooses the nonanxious picture, his anxiety score will be 0. The anxiety scores are then summed, resulting in total scores ranging from 0 to 8. If the child’s score is four or higher, they will be considered an anxious child27. It is a robust measure for the Iranian population, with moderate correlations and significant p-values with the RMS-PS and FIS anxiety questionnaires, and reliable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82)28.

Collection of data

The intervention group consisted of two groups of school-aged children. The stress ball squeezing group included children who squeezed a stress ball five minutes before and during intravenous catheter insertion. The pinwheel blowing group included children who blew a pinwheel five minutes before and during intravenous catheter insertion. The control group included children who received routine ward care (only an intravenous catheter was inserted by a nurse).

To ensure that the conditions were the same for all three groups during the study period, an authorized nurse inserted the intravenous catheter with only one attempt. First, after providing the necessary explanations and informed verbal and written consent from parents and school-age children, the researcher completed a demographic information form. The child was transferred to the intravenous catheter insertion room with the parent, and to measure the level of anxiety and pain, a self-reported anxiety and pain scale was completed before the intervention. Five minutes before the insertion of the intravenous catheter, distraction was started by squeezing a stress ball or blowing a pinwheel with the hand opposite to the one used to insert the intravenous line. Then, the catheter was inserted, and distraction continued until the end of the intravenous catheter insertion. The duration of intravenous catheter insertion was calculated from the moment of needle insertion to the stage of fixing the angiocatheter. As soon as the angiocatheter was inserted and immediately after the end of the intravenous line insertion (as soon as the angiocatheter was fixed), the pain and anxiety scores were determined via the Oucher tool and the Venham tool, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed via the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows (version 25.0) at a significance level of 0.05. The data analysis process included descriptive statistics such as numbers and percentages, as well as means and standard deviations. Additionally, the data were analyzed via various statistical tests. The chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of qualitative demographic data between the three study groups. Due to the non-normal distribution of the data, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare quantitative data among the three study groups, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare quantitative data between pairs of study groups.

Ethical considerations

To conduct this study, permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Clinical Research via an ethical consent form. The aim and method of the study were explained to the children and their parents, and they were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without stating a reason if they did not wish to continue. Written informed consent was obtained from the children and their parents. The children and their parents were assured that the information they provided would be confidential and would not be used for any other purpose. The study thus fulfilled all the relevant ethical principles of informed consent, voluntariness, and protection of the privacy of human subjects, safeguarding their rights. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (ID- code: IR.SUMS.NUMIMG.REC.1402.153).

Results

This study included 90 children: 50 girls (55.6%) and 40 boys (44.4%). The mean age of the children was 9.40 ± 2.23 years (range: 6–12 years). The children were randomized into three groups: the stress ball (n = 30), pinwheel (n = 30), and control (n = 30) groups. The characteristics of the children are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found between the control and intervention groups in terms of the child’s age, sex, mother’s age, mother’s education, father’s age, father’s education, child’s birth rank, family residence, child’s hospitalization, child’s history of hospitalization and number of hospitalizations, date of child’s current hospitalization, child’s history of previous intravenous catheter insertion, history of any needle insertion such as an ampoule or blood draw, child’s sibling’s hospitalization history, location of intravenous catheter insertion, parent who was with child when intravenous catheter was inserted, or angiocatheter size (P > 0.05; Table 1). Chi-square tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed to examine the significance of potential factors affecting children’s ratings of postprocedural pain and anxiety. However, we found no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of the aforementioned contextual variables (P > 0.05). These findings suggest that the groups are similar in terms of demographic variables that may affect the perception of pain and anxiety.

The pain levels of patients in the study groups are shown in Table 2. The results of the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant difference in pain between the control and intervention groups during intravenous catheter insertion (P < 0.001). The Mann–Whitney test showed that there was a statistically significant difference in pain scores during the intervention between the control and stress ball groups (P < 0.001), the control and pinwheel groups (P < 0.001), and the stress ball and pinwheel groups (P = 0.042). The pinwheel group had the lowest mean pain score (Table 3).

The anxiety level evaluation of the study groups is presented in Table 2. The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant difference in anxiety between the control and intervention groups during and after intravenous catheter insertion (P < 0.001). The Mann-Whitney test revealed statistically significant differences in anxiety scores during the intervention between the control and stress ball groups (P < 0.001) and between the control and pinwheel groups (P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in anxiety scores during the intervention between the stress ball and pinwheel groups (P = 0.332). There was also a statistically significant difference in anxiety scores after the intervention between the control and stress ball groups (P = 0.002) and between the control and pinwheel groups (P = 0.037). There was no statistically significant difference in anxiety scores after the intervention between the stress ball and pinwheel groups (P = 0.418) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, the effects of two different active distraction methods (stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing) on the pain and anxiety levels of children during intravenous catheter insertion were evaluated. These methods have been chosen because the materials are readily available, and the intervention is non-time-consuming and does not require specialized training. These factors make these interventions suitable for use in busy hospital units such as the phlebotomy unit.

This study showed that squeezing a stress ball is an effective method for reducing pain and anxiety caused by intravenous catheter insertion in hospitalized school-aged children. This result supported the first and second hypotheses (The stress ball squeezing group will experience less pain and anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion compared to the control group). Few RCTs have investigated the effects of ball squeezing on venipuncture/phlebotomy pain and anxiety management in children of a similar age group6,18,20,21,29. A study comparing balloon inflation, ball squeezing, and coughing for mean pain and fear scores from venous blood sampling in children aged 7–12 years revealed that the mean pain and fear scores were significantly lower in all intervention groups than in the control group. There was no significant difference in pain or fear scores between the intervention groups6. In a study comparing the effects of bubble-making and ball-squeezing on mean pain and fear scores during venous blood sampling in children aged 7–12 years, the results revealed that the mean pain and fear scores in each intervention group were significantly lower than those in the control group. The bubble-making group exhibited significantly less fear than the stress ball-squeezing group; however, there was no significant difference in pain scores between the two intervention groups21. In another study that compared balloon inflation, ball squeezing, and distraction cards in terms of the mean pain and fear scores during venous blood sampling in children aged 7–12 years, the results revealed that ball squeezing reduced children’s pain during venous blood sampling, although the reduction in pain from ball squeezing with that in the control group was not statistically significant. The results of the present study are inconsistent with those of the previous research. In the present study, ball squeezing significantly reduced pain during intravenous line placement compared with the control group. The difference in the results reported by Aydin et al. and those of the present study could be attributed to variations in the procedures performed (venous blood sampling versus intravenous line placement), the questionnaires used, and the study populations20.

This study demonstrated that pinwheel blowing is an effective method for reducing pain and anxiety caused by intravenous catheter insertion in hospitalized school-aged children. This result supported the third and fourth hypotheses (The pinwheel blowing group will experience less pain and anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion compared to the control group). The pinwheel blowing technique has been used in a limited number of studies19,30. A study comparing pinwheel blowing and the cough trick in children aged 6–12 years during venipuncture found that pain scores were significantly lower in both intervention groups compared to the control group, suggesting that distraction techniques—particularly the cough trick—effectively reduce pain perception in children undergoing venipuncture30. In another study comparing deep breathing and paper whirligigs in terms of mean pain scores from venous blood sampling in children aged 6–12 years revealed that the mean pain scores were significantly lower in all intervention groups than in the control group. There was no significant difference in pain scores between the intervention groups. However, children in the paper whirligigs group had the lowest mean pain scores19. In the preschool age group (4 to 6 years), the use of pinwheels was found to reduce pain and anxiety during blood sampling31. Our results confirm the results of earlier RCTs.

Distraction techniques, such as squeezing a stress ball and blowing a pinwheel, have been shown to reduce pain and anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion in children effectively. According to McCaul and Malott, the brain has a limited capacity for processing external stimuli, and when attention is directed toward an engaging or distracting task, the brain’s ability to focus on painful stimuli is reduced32. They further suggest that distraction activates internal pain-suppression mechanisms and modulates nociceptive responses. This cognitive perspective aligns with the physiological explanation provided by the gate control theory of pain, proposed by Melzack and Wall. According to this theory, non-painful sensory inputs—such as those generated during distraction—can inhibit pain transmission by activating large-diameter A-beta fibers that “close the gate” at the spinal cord level, thereby blocking pain signals from smaller nociceptive fibers33. Together, these cognitive and physiological mechanisms help explain why distraction-based interventions, such as squeezing a stress ball and blowing a pinwheel, are effective in reducing procedural pain and anxiety in children.

All groups were compared pairwise. The results showed that both intervention groups (stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing) experienced significantly lower levels of pain and anxiety compared to the control group. Furthermore, when comparing the two nonpharmacological methods, pinwheel blowing was more effective in reducing pain. This result supported the fifth hypothesis (Stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing have different effects on the average pain scores resulting from intravenous catheter insertion in school-aged children). However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two intervention groups in terms of anxiety reduction; therefore, this result did not support the sixth hypothesis (Stress ball squeezing and pinwheel blowing have different effects on the average anxiety scores resulting from intravenous catheter insertion in school-aged children).

Both pinwheel blowing and stress ball squeezing were effective nonpharmacological interventions that significantly reduced pain and anxiety during intravenous catheter insertion in school-aged children. Among these, pinwheel blowing proved more effective in alleviating procedural pain. Future research should investigate the effects of these methods on various painful procedures across different pediatric age groups. Evidence-based guidelines and clinical protocols should be developed to incorporate these techniques into pediatric pain and anxiety management. Nursing educators can incorporate these findings into training programs, and the results can provide practical guidance for nursing managers and nurses working in pediatric wards.

Limitations

Owing to the self-reported nature of the Pain and Anxiety Questionnaire, it is possible that the school-aged children in the study did not report reality while completing the questionnaire. Children may react differently to pain and anxiety based on their physical condition, emotional state, and cultural background. Finally, data obtained via scales are not supported by objective, physiological measurements (e.g., heart rate, pulse, respiration), which can be considered a limitation.

Conclusion

Both pinwheel blowing and stress ball squeezing reduced pain and anxiety during IV insertion in school-aged children, with pinwheel blowing being more effective for pain relief. These low-cost, accessible methods can support pediatric care. Further research should explore broader applications and inform clinical guidelines.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hockenberry, M. J., Wilson, D. & Rodgers, C. C. Wong’s nursing care of infants and children. 11th edition ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; (2019).

Ates Besirik, S. & Canbulat Sahiner, N. Comparison of the effectiveness of three different distraction methods in reducing pain and anxiety during blood drawing in children: A randomized controlled study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 79, 225–233 (2024).

Canbulat Sahiner, N., Ates Besirik, S., Koroglu, A. Y. & Dilay, S. The effectiveness of using animal-themed vacutainers to reduce pain and fear in children during bloodletting. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 78, 101549 (2025).

Ali, S. et al. Virtual reality-based distraction for intravenous insertion-related distress in children: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 12 (3), e057892 (2022).

Stone, J. Decreasing pain and anxiety in pediatric vascular access procedures: guest editorial. J. Association Vascular Access. 29 (1), 6–7 (2024).

Aykanat Girgin, B. & Göl, İ. Reducing pain and fear in children during venipuncture: a randomized controlled study. Pain management nursing. Official J. Am. Soc. Pain Manage. Nurses. 21 (3), 276–282 (2020).

Kleye, I. et al. Increasing child involvement by Understanding emotional expression during needle procedures: A video-observational intervention study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 81, e24–e30 (2025).

Saad, L. & Hassan, S. Alternative treatments for nsaids: a comprehensive review. Indian J. Appl. Research 14, 5–7 (2024).

Antos, Z., Zackiewicz, K., Tomaszek, N., Modzelewski, S. & Waszkiewicz, N. Beyond pharmacology: a narrative review of alternative therapies for anxiety disorders. Diseases 12(9), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12090216 (2024).

Mohamed Bayoumi, M. M., Khonji, L. M. A. & Gabr, W. F. M. Are nurses utilizing the non-pharmacological pain management techniques in surgical wards? PloS One. 16 (10), e0258668 (2021).

Erdogan, B. & Aytekin Ozdemir, A. The effect of three different methods on venipuncture pain and anxiety in children: distraction cards, virtual reality, and buzzy® (randomized controlled trial). J. Pediatr. Nurs. 58, e54–e62 (2021).

van Veen, S. et al. Non-pharmacological interventions feasible in the nursing scope of practice for pain relief in palliative care patients: a systematic review. Palliat. Care Social Pract. 18, 26323524231222496 (2024).

Møller-San Pedro, A. J., Fisker, L. Y. V., Pedersen, L. K. & Møller-Madsen, B. Non-pharmacological treatment for pediatric pain and anxiety. Ugeskr. Laeger. 186 (2), V06230364–V (2024).

Checa-Peñalver, A. et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in the management of pediatric chronic pain: a systematic review. Children (Basel Switzerland) 11(12), 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121420 (2024).

Inan, G. & Inal, S. The impact of 3 different distraction techniques on the pain and anxiety levels of children during venipuncture: a clinical trial. Clin. J. Pain. 35 (2), 140–147 (2019).

Thomas, A. R. & Unnikrishnan, D. T. Comparison of animation distraction versus local anesthetic application for pain alleviation in children undergoing intravenous cannulation: a randomized controlled trial. Cureus 15 (8), e43610 (2023).

Shahrbabaki, R. M., Nourian, M., Farahani, A. S., Nasiri, M. & Heidari, A. Effectiveness of listening to music and playing with Lego on children’s postoperative pain. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 69, e7–e12 (2023).

Sarman, A. & Tuncay, S. Soothing venipuncture: bubble blowing and ball squeezing in reducing anxiety, fear, and pain in children. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatric Nursing: Official Publication Association Child. Adolesc. Psychiatric Nurses Inc. 37 (3), e12478 (2024).

Abdolalizadeh, H., NamdarArshatnab, H., Janani, R. & Arshadi Bostanabad, M. Comparing the effect of two methods of distraction on the pain intensity venipuncture in school-age children: a randomized clinical trial. J. Pediatr. Perspect. 6 (10), 8423–8432 (2018).

Aydin, D., Şahiner, N. C. & Çiftçi, E. K. Comparison of the effectiveness of three different methods in decreasing pain during venipuncture in children: ball squeezing, balloon inflating and distraction cards. J. Clin. Nurs. 25 (15–16), 2328–2335 (2016).

Oluc, N. & Tas Arslan, F. The effect of two different methods on reducing the pain and fear during phlebotomy to children: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 72, 101386 (2024).

Lilik Lestari, M. P., Wanda, D. & Hayati, H. The effectiveness of distraction (cartoon-patterned clothes and bubble-blowing) on pain and anxiety in preschool children during venipuncture in the emergency department. Compr. Child. Adolesc. Nurs. 40 (sup1), 22–28 (2017).

Beyer, J. E. & Aradine, C. R. Content validity of an instrument to measure young children’s perceptions of the intensity of their pain. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 1 (6), 386–395 (1986).

Sharifian, P., Khalili, A. & Cheraghi, F. The effect of auditory distraction on pain of dressing change in 6–12 years old children: a clinical trial study. J. Health Care. 22 (2), 147–156 (2020).

Esmaeili, K., Iranfar, S., Afkary, B. & Abbasi, P. The comparison of the effect of music and rhythmic breathing techniques on pain severity of intravenous cannulation during blood transfusion. J. Kermanshah Univ. Med. Sci. 12 (2), 129–139 (2008).

Babaei, Alhani, F. & Khaleghipour, M. Effect of mother’s voice on postoperative pain pediatric in tonsillectomy surgery. Iran. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 3 (2), 51–56 (2016).

Venham, L. L. & Gaulin-Kremer, E. A self-report measure of situational anxiety for young children. Pediatr. Dent. 1 (2), 91–96 (1979).

Javadinejad, S., Soheilipour, F., Jaderi, P. & Nasr, N. A reliability and validity of the Rms pictorial scale in comparison with facial image scale and Venham picture test for assessment of child anxiety. J. Isfahan Dent. School. 14 (2), 207–214 (2018).

Gerçeker, G. Ö., Bektaş, İ. & Yardımcı, F. The effects of virtual reality and stress ball distraction on procedure-related emotional appearance, pain, fear, and anxiety during phlebotomy in children: A randomized controlled study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 79, 197–204 (2024).

Merter, O. S., Sengul, Z. K. & Oguz, R. Effects of blowing pinwheel and cough trick on pain in 6- to 12-year-old children during venipuncture: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 83, 30–37 (2025).

Dinç, F., Kurt, A. & Güneş Şan, E. The effect of three different methods on pain and anxiety in children during blood sampling procedure in pediatric emergency department: finger puppet, Abeslang puzzle, pinwheel. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 79, e203–e12 (2024).

McCaul, K. D. & Malott, J. M. Distraction and coping with pain. Psychol. Bull. 95 (3), 516–533 (1984).

Melzack, R. & Wall, P. D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Sci. (New York NY). 150 (3699), 971–979 (1965).

Acknowledgements

This study is derived from a Master’s degree student’s thesis on pediatric nursing. The authors would like to thank the Vice President for Research and Technology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for their financial support, the personnel of Namazi Hospital, and the parents and children who participated in this project.

Funding

Shiraz University of Medical Sciences supported this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H.S., Z.J., N.S., and R.D.D. contributed to the study design. R.D.D. ran the study and collected the data. N.S. and R.D.D. conducted the primary data analyses and provided the primary data interpretation. Z.H.S. and R.D.D. drafted the manuscript. Z.H.S., Z.J., and N.S. provided critiques to refine the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was confirmed by the Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (ID- code: IR.SUMS.NUMIMG.REC.1402.153). All participants provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent before the interview. It is worth noting that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All steps in this study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dehnavi, R.D., Sharifi, N., Jamshidi, Z. et al. Pinwheel blowing and stress ball squeezing reduce children’s pain and anxiety during intravenous catheterization in a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 31359 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17250-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17250-4